Abstract

In a globalized world, the expatriate community continues to expand. Selecting trustworthy healthcare providers is fundamental for their adaptation to a new country. Through interviews and a survey, this paper adds to the literature by theoretically discussing and empirically analyzing the decision process of a cross-cultural sample of expatriates in Dubai. It focuses on evaluating the role of two cues: Country of Origin (COO) and Word of Mouth (WOM). The findings show personal WOM is the most influential factor. The paper also explores the effect of expatriates’ origin (developed vs. emerging countries) and their levels of fluency in English.

Introduction

When companies launch a new product or enter new markets, it is necessary to invest to improve brand awareness so the product can be considered as an alternative by consumers and will be present on their mental map (Aaker Citation1991; Keller Citation1993). In markets where expatriates represent a significant share of consumers, global brands have an advantage over local brands as the former are easily recognized by those new consumers. In the case of the healthcare sector, however, most providers carry local unknown brands for the new consumers.

Many studies discuss the means of choosing a healthcare provider in different contexts, mostly in countries that adopt a referral system. This study analyzes expatriates’ healthcare provider selection process, by assessing the importance of COO, WOM and the traditional aspects that support their decision. COO is a cue in the buyer’s perception (Bilkey and Nes Citation1982), and when a new brand is introduced, it is a key element in consumers’ decision process (Ryu, Park, and Feick Citation2006). As expatriates arrive in a new country, they can use the COO (nationality) of a healthcare professional or the hospital brand association to a country as a proxy-rating of quality. A second cue adopted by consumers is WOM (Brown and Reingen Citation1987), which in case of unfamiliarity, can have more influence on consumer behavior than paid advertising (Parry, Kawakami, and Kishiya Citation2012).

To the best of our knowledge there is no research on COO and WOM as cues on the decision-making process to select a healthcare provider. Most studies on expatriates focus on relocation and adaptation.

We developed the research in Dubai, an emirate with a diverse population of expatriates who are mostly covered by private health insurance and that can choose doctors and dentists (International Insurance Citation2021). This situation results from a 2014 law which determined that by 2017, every employee and their dependents living in Dubai should be covered by medical insurance (Dubai Health Authority Citation2019). Expatriates that earn less than 4,000 dirhams (US$1,090) a month are granted with the Essentials Benefits Plan (or EBP), which offers basic medical care coverage. Employers who earn over this amount can choose other coverage options outside of the EBP, as long as it offers at least the basic benefits offered through EBP (International Insurance Citation2021).

Previous research on COO revealed differences in perception between consumers from developed and emerging countries (Hsieh Citation2004; Sharma Citation2011; Sheth Citation2011; Cilingir and Basfirinci Citation2014; Costa, Carneiro, and Goldszmidt Citation2016). Given the diversity of nationalities among expatriates in Dubai, this study aims to investigate whether the level of development of consumer’s country of origin (i.e., originally from a developed vs. emerging country) impacts the effect of COO on their decision process.

To fulfill the purposes of this investigation, we put forward the following research questions: 1) How do expatriates find out about a healthcare provider in their first appointment after relocating to a new place? 2) What are the key factors considered and how do expatriates prioritize them when seeking a healthcare provider? 3) Does expatriates’ nationality (developed or emerging country) moderate COO impact?

Literature and hypothesis

Expatriates

The first research on expatriates started in the 1950s, when American firms began sending their employees abroad. Since then, research has been concentrated on organizational expatriates (OEs) (Cerdin and Selmer Citation2014) and focused on their adaptation, challenges, and decision process to live overseas (McNulty and Brewster, Citation2017). Scholars classify expatriates in different ways. Andresen et al. (Citation2014) describe self-initiated expatriates (SIEs) as employees not sponsored by an organization who are consequently unlikely to gain career benefits. Farcas and Gonçalves (Citation2017) define migrant workers, namely assigned expatriates (AEs), and immigrant workers (IWs). Expatriates differ from immigrants as their stay in a country has a limited time span.

According to the International Organization for Migration (International Organization for Migration (IOM), Citation2018, International Organization for Migration (IOM)), Citation2020), in the 1990-2019 period, the global migrant population more than doubled, going from 130 million to 272 million. In the UAE, where Dubai is located, the increase in the number of expatriates has been staggering at a compound annual rate of 5.8%, between 2013 and 2019, when it reached 8.58 million (IndexMundi Citation2021). According to Dubai Statistics Center (DSC) (Citation2020), in 2020 expatriates represented over 92% of the population.

Shaffer, Harrison, and Gilley (Citation1999) classify expatriate adjustment in a new country, based on adaptation to housing, shopping, entertainment, food, and healthcare consumption. Healthcare is among expatriates’ top priorities when moving to a new country (InterNations Citation2021). Research on expatriates’ adjustment to a new place shows that healthcare scored at the bottom of the areas to which they adapt when they relocate to a new country (Miocevic and Zdravkovic Citation2020; Shaffer, Harrison, and Gilley Citation1999). Concomitantly, with the surge in the number of people moving around the world, there has been an increase in the interest in their buying decisions. Steenkamp (Citation2019) posits two patterns to assess expatriates’ decision process research. The first is cultural homogenization via global brands or Global Consumer Culture (GCC) and the other is Local Consumer Culture (LCC) which includes opportunities to empower local brands by associating them to the local culture (Steenkamp Citation2019). Among the over 60 clinics and hospitals in Dubai, there is a predominance of brands named after a person, associated with the neighborhood where it is located, a country or a specialty. There was only one brand originally from South Africa and with branches in Namibia, Switzerland and the UAE and an India-based hospital (Yellow Pages United Arab Emirates, Citation2021). Therefore, the expatriates’ purchase decision process for healthcare providers fits into an LCC pattern.

Healthcare services purchase decision process

Petty, Cacioppo, and Schumann (Citation1983) argued that the greater the consumer’s involvement, the more effort they will exert to search for relevant information for the decision process. Healthcare services commonly relate to uncertainty and risk. Therefore, hiring a healthcare service is a high involvement purchase decision (Lu and Wu Citation2016). According to Berentzen et al. (Citation2008), dealing with international consumers presents challenges that require healthcare providers to customize and adapt to different cultures.

Patient choice for healthcare is a topic that has been raising attention in health management (Dixon et al. Citation2010; Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017). Victoor et al. (Citation2012) showed that some patients actively search for providers, while others rely on their General Practitioner (GP) for advice. The amount of effort spent to seek a healthcare provider varies by patients’ characteristics. The more vigorous searchers are the ones who are highly educated, younger, with higher incomes, and without an existing relationship with a healthcare provider, a profile that applies to the case approached in this research.

Abraham et al. (Citation2011) state that financial incentives and consumers’ possibility of accessing information influence their ability and motivation to engage in the decision process of selecting a healthcare provider.

Several studies identify common aspects influencing patients’ selection of a healthcare provider. The topmost are location or accessibility (Burge et al. Citation2004; Wun et al. Citation2010; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012; Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017); physical appearance of the doctor’s office, clinic, hospital and the physician per se (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000); the reputation of the professional and/or hospital/clinic (Burge et al. Citation2004; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017, Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017); qualification of the professional, which includes if physicians are board certified, their specialization and where they got their degree and residency (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012) and staff kindness (Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017, Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017) and, when applicable, if the professional is in the insurer’s network (Abraham et al. Citation2011). Factors that have lower influence in patients’ decisions include advertisements and websites (Abraham et al. Citation2011); doctor’s demographics, including native country (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000).

From the literature review and considering the characteristics of Dubai medical and dental healthcare system which follows strict rules and quality control from the government (Dubai Health Authority Citation2019), besides WOM and COO, this study considered the following factors to understand expatriates’ healthcare purchase decision process: 1) accessibility (location); 2) credibility of the institution where the physician/dentist works; 3) the institution where the doctor/physician got the medical degree, and 4) physician/dentist years of experience.

Word of mouth (WOM)

Word of Mouth (WOM) comprises a noncommercial communication about a product, a service, or a brand product among consumers (Arndt Citation1967). It is more powerful than information sponsored by manufacturers or marketing partners (Duhan et al. Citation1997) and is an effective tool to move consumers from awareness to trial (Engel, Kegerreis, and Blackwell Citation1969).

WOM can come in different formats, such as a recommendation, comment, suggestion, or review. Its strength relates to the fact that personal sources of information such as family members, friends, acquaintances, and customers, who do not benefit from the sale of one product over another, have more impact on consumer behavior than paid advertising (Parry, Kawakami, and Kishiya Citation2012).

Zeithaml (Citation1981), who proposed a continuum of products’ evaluation from easy to difficult, positioned medical diagnosis performed by healthcare providers as the most difficult to evaluate. To minimize the difficulty of dealing with the decision process of selecting a healthcare provider, consumers rely on personal sources (WOM) (Zeithaml Citation1981; Murray Citation1991). WOM is especially important in professional services and medical care services where there is a high involvement because of the risk and uncertainty related to the outcome of the service (File, Cermak, and Prince Citation1994; File, Judd, and Prince Citation1992; Ferguson, Paulin, and Leiriao Citation2006).

Consumers resort to WOM to choose a new product or service (Brown and Reingen Citation1987), or to decide on a physician (Feldman and Spencer Citation1965). Specialized healthcare providers rarely use mass media or strong advertising techniques, therefore WOM is especially relevant to help generate sales (Ferguson, Paulin, and Leiriao Citation2006).

There are different ways to classify WOM. Arndt (Citation1967) pointed its content can be positive, neutral, or negative, while most research focuses on positive or negative personal experiences (Brown, Collins, and Schmidt Citation1988; De Angelis et al. Citation2012; Buttle Citation1998; Curasi and Norman Kennedy Citation2002). Negative WOM is more persuasive and propagates faster (Arndt Citation1967; Herr, Kardes, and Kim Citation1991). Ferguson, Paulin, and Leiriao (Citation2006) categorize WOM as passive or active. File, Cermak, and Prince (Citation1994) classify WOM by the proximity or distance between the source and the person requesting or exposed to information. Another classification for WOM cue is by whether it was obtained as an input during the pre-purchase stage (InputWOM) or as an output provided in the post-purchase phase (OutputWOM) (Hennig-Thurau et al. Citation2004). In a digital age, scholars also differentiate personal word of mouth (pWOM) from a virtual worth of mouth (vWOM) (Parry, Kawakami, and Kishiya Citation2012), also referred as eWOM (Hennig-Thurau et al. Citation2004) or online WOM, which includes blogs and discussion groups, in opposition to offline WOM (Lovett, Peres, and Shachar Citation2013). Dubois, Bonezzi, and De Angelis (Citation2016) evaluated the effect of WOM interpersonal closeness (IC) by the strength of the ties - weak or strong - between provider and receiver of information on online and offline communities.

Different researchers have associated WOM with one of Hofstede’s cultural dimensions: Collectivism vs. Individualism explained as “the extent to which people feel independent, as opposed to being interdependent as members of larger wholes. (…) embedded in a closely connected group (collectivism).” (Hofstede Citation2013). According to Goodrich and de Mooij (Citation2014, p. 106) “In collectivistic cultures, people meet others more frequently and there is more interpersonal communication” than in individualistic cultures and that behavior is extended to WOM. Dang and Raska (Citation2021) found that collectivist countries count more on eWOM. Madupu and Cooley (Citation2010) research on American (individualistic culture) and Indian consumers (collectivist culture) and the study indicates that the latter are more motivated to share information.

A service provider can affect the frequency and direction of output WOM by how they handle complaints and service guarantees (File, Cermak, and Prince Citation1994). Input WOM is more significant in the purchase of services with high risk (Hugstad, Taylor, and Bruce Citation1987), high involvement (Webster, 1988), and greater complexity of evaluation (Hill Citation1988), and when buyers are less knowledgeable about the product (Herr, Kardes, and Kim Citation1991) or a brand (Lovett, Peres, and Shachar Citation2013). Therefore, the process through which first-time expatriates select a healthcare provider fits into those categories: it is a risky, high involvement, complex service purchased with a low level of knowledge.

Consumers value more pWOM than vWOM because they have greater identification with the former (Duhan et al. Citation1997). However, if vWOM sources expose new customers to a broader variety of information, it may have a larger impact on perceptions than pWOM (Parry, Kawakami, and Kishiya Citation2012).

Research shows the importance of WOM in patients’ decision process (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000; Abraham et al. (Citation2011); Wun et al. Citation2010; Duran, Cetindere Filiz, and Cetindere Citation2016). Bornstein at al. (2001) identified the relevance of WOM in patients’ decision process as being one of the most important elements after board certification, professional’s office, personal appearance and, above where healthcare providers got their degree, the number of years of practice and their nationality. Duran, Cetindere Filiz, and Cetindere (Citation2016) posit that WOM plays a significant effect on customers’ preferences for healthcare services. When asking for advice, patients will prioritize in the following order: friends, relatives, and healthcare workers. The findings of their study showed women are more prone to be influenced by WOM than men regarding healthcare services.

According to Ferguson, Paulin, and Leiriao (Citation2006), the WOM sources of recommendation for medical care services will be former patients, acquaintances of the healthcare provider, and health professionals. Dixon et al. (Citation2010) identified that when the healthcare system requires that patients consult with a GP, those become the main source of information to select a hospital, followed by friends and family, whereas a national health service website was less significant.

When expatriates select a healthcare provider, among the common aspects influencing regular patients’ decision process (WOM, location, years of experience, and institution where the physicians got their degree), WOM will be the most relevant because of the lack of awareness of healthcare services providers.

Hypothesis 1: When selecting a healthcare provider, personal WOM will be the most important factor in expatriates’ decision process

Country of origin effect

Research on the country-of-origin (COO) effect on consumers’ evaluations of products manufactured abroad started in the 1960s (Schooler Citation1966; Relerson Citation1966) and focused on evaluating bias and quality perception (Bilkey and Nes Citation1982). In the following decades, the studies also encompassed countries (Nagashima Citation1970; Gaedeke Citation1973), industrial buyers, consumer packaged goods, services and the relationship between COO and consumers’ perceptions of products (Bilkey and Nes Citation1982; Min Han Citation1989, Eroglu and Machleit Citation1989).

Over the years, different reasons justified the diversification of COO studies, including: companies started producing in multiple locations to reduce transportation costs (Pappu, Quester, and Cooksey Citation2007); there was an increase in brand options (Erickson, Jacobson, and Johansson Citation1992; Eroglu and Machleit Citation1989; Paswan and Sharma Citation2004), the relationship between brands and nations needed to be investigated (Gϋrhan-Canli and Maheswaran Citation2000; Amine and Shin Citation2002; Aichner Citation2014), product association with COO became more relevant to consumers’ decision process (Paswan and Sharma Citation2004); consumers considered locations where products are designed, manufactured, transformed, exported, or mostly consumed (Roth and Romeo Citation1992) and consumers valued a brand and a product by their origin (Koubaa, Boudali Methamem, and Fort Citation2015).

Mort and Duncan (Citation2003) identified two ways to address COO’s cue: “owned by…” and “made in …”. For this study, we considered that the nationality of the healthcare provider and the brand of the institution would function as a cue of COO “made in…”.

Aichner (Citation2014) classifies COO markers in two groups: regulated and unregulated. The former carry an association by adopting “owned by…” and “made in …”, while the latter can be embedded in brands in ways such as Alitalia (Italy) and Air France (France), or by including COO words, such as in Lincoln National or Dr. Oetker which consumers relate to the U.S. and Germany, respectively.

Maheswaran (Citation1994) and Lee and Lee (Citation2009) examined the effect of COO on novice and expert consumers and concluded that consumers with low familiarity with a category are more likely to access COO in their evaluation. Expatriates searching for information on a healthcare provider for the first time after they moved to a new place are novice consumers.

Consumers’ reactions vary under the level of development of the country manufacturers. Products from large developed markets are considered more trustworthy than products from developing markets (Tang Citation2017). Consumers tend to evaluate their own country’s products relatively more favorably than foreigners (Nagashima Citation1970; Bilkey and Nes Citation1982). In the Netherlands, a country that offers universal access healthcare (UHC) system, more than half of the non-European ethnic minority citizens aged 55 years or older reported preferring going back to their country of origin for healthcare services (Şekercan et al. Citation2015).

The strength of COO in purchase decision varies by nationality. Consumers from developing countries are more sensitive to it than those from developed ones (Hsieh Citation2004; Sharma Citation2011; Costa, Carneiro, and Goldszmidt Citation2016).

The effect of COO may vary among service categories (Michaelis et al. Citation2008). Berentzen et al. (Citation2008) research on risky services indicates that similarly to WOM, COO functions as a quality indicator to diminish perceived risk. For instance, the impact of the impact of COO on the banking service category is lower than that for airlines, which presents a higher risk for the consumers. This happens because, for high-risk services, it is hard to compensate for a negative COO using additional quality cues (Berentzen et al. Citation2008).

Eroglu and Machleit (Citation1989) claim that the predictive value of COO can vary depending on: 1) product class involvement, 2) technical complexity of the product, 3) previous consumer experience, and 4) consumers’ ability to perceive inter-brand differences. In a situation of choosing a healthcare provider in a new market, COO would come as a product quality cue (Eroglu and Machleit Citation1989). Along with the challenging characteristics of services - intangibility, perishability, heterogeneity, and inseparability (Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Berry Citation1985), marketing healthcare services to a diverse expatriate community presents special challenges that require extensive customization (Berentzen et al. Citation2008).

Amine and Shin (Citation2002) postulate that consumers prefer products based on their proximity and knowledge of the country of origin. Expatriates will attribute more importance to COO than traditional aspects considered in the decision process as location, organization reputation or years of experience of the physician/dentist.

Hypothesis 2a: When selecting a healthcare provider, COO is more important than the traditional factors in expatriates’ decision process.

Concerning preference for COO, Hsieh (Citation2004) highlights consumers have a greater inclination toward products from their own countries and countries in the same geographic region. The findings from the exploratory stage of this research demonstrated that patients understand COO in different ways: “Nationality of the physician/dentist”; “The physician/dentist has the same nationality as and the country of reference of the hospital or clinic (e.g., American Clinic)”. For expatriates dealing with a high involvement and a high-risk service, healthcare providers with the same nationality will stand out.

Hypothesis 2b: A healthcare provider with the same nationality as the patient will be even more relevant in the expatriates’ decision process than other COO factors.

The moderating role of expatriates’ COO - developed and emerging countries

In a diverse global economy, scholars have been investigating how the level of economic development impact consumer behavior. Previous research suggests that consumers’ nationality - consumers from a developing/emerging or a developed country - will moderate COO (Hsieh Citation2004; Sharma Citation2011; Costa, Carneiro, and Goldszmidt Citation2016).

Cilingir and Basfirinci (Citation2014) and Sheth (Citation2011) argue that consumer behavior differs between emerging markets and developed ones. When making purchase decisions, consumers from developed markets are more ethnocentric and inclined to buy locally made products (Cilingir and Basfirinci Citation2014). Batra et al. (Citation2000) argue that consumers in emerging/developing markets are keen to consume non-local brands.

On this basis, this study speculates that expatriates from developed and emerging countries have a different perspective on the impact of COO in the decision process and selecting a healthcare provider and, therefore, that respondents’ nationality will moderate the impact of COO effect in their decision process. Expatriates from developed markets would prefer a healthcare provider of their nationality (local made).

Hypothesis 3: Expatriates’ nationality - developed vs. emerging country moderate the relationship between COO factor and the decision process toward a healthcare provider.

Expatriates from developed countries will care more about having a healthcare provider of their nationality than expatriates from emerging countries will.

The grouping of respondents in developed and emerging countries followed the classification of the International Monetary Fund (Citation2021).

The moderating role of English proficiency when expatriates decide on a healthcare provider

The UAE is home to a great number of nationalities, with a higher concentration of migrants from India (40%), Bangladesh (13%), Pakistan (11.5%), Egypt (10%), Philippines (6.5%), Indonesia (3.7%), Yemen (2.4%) and Jordan (1.9%) (Dubai Online, Citation2021). That diversity explains why, despite Arabic being the official language in the emirate, English is the “lingua franca”, the language of international business, casual conversations, and used in most educational institutions (Seidlhofer Citation2001). All road and traffic signs, official information on government and business websites are in Arabic and English.

Language plays an important role in socialization and relationship and is a fundamental dimension of culture identity (Brown Citation2014) and in understanding a culture (Selmer Citation2006). It is the major channel through which cultural information and heritage are exchanged and shared (Kang Citation2006) and it plays a key role in the adjustment process (Caligiuri et al. Citation2001), as language ability facilitates expatriates cultural and social adjustment (Selmer Citation2006).

According to Farcas and Gonçalves (2016) adjustment situation applies to expatriates who will spend a limited time in the host country. Gudykunst (Citation1985) identified three major factors affecting communication between people of different cultures - cultural similarity/dissimilarity, second language fluency, and previous experience in the other culture. Interaction with healthcare providers require from patients, the capacity to exchange sensitive information and understanding diagnoses and recommendations.

The EF English Proficiency Index (EF International Language Centers, Citation2020) evaluates around 90 countries’ proficiency in English as a second language organizing them in five groups - very high proficiency, high proficiency, moderate, low, and very low proficiency group. We classified the respondents of the study relating their nationality to those proficiency categories.

Hypothesis 4: Expatriates’ English proficiency moderates the relationship between COO and decision process toward a healthcare provider.

Expatriates with low and very low English proficiency will care more about having a healthcare provider of their nationality than expatriates with moderate and high proficiency.

Conceptual framework

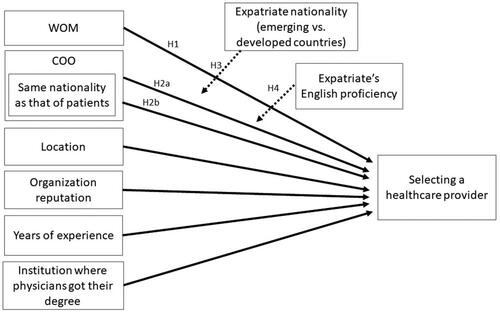

We developed a research conceptual framework based on the literature review and the hypotheses illustrated in .

Method

The research started with 12 personal face-to-face in-depth interviews with expatriates from a variety of nationalities with the purpose of understanding expatriates’ behavior over selecting a healthcare provider. They were recruited in an Arabic course attended by expatriates. The interviewees’ sources of information to find out about a healthcare provider included health insurance and hospital/clinic websites, online research, a social media community, and references from a coworker or a friend. Interviewees considered the following factors in their decision-making process: physicians’ nationality, the institution where they got their degree, their years of experience, the country where they worked, if the nationality was the same as that of the interviewee. Regarding the institution where the professional works, the interviewees mentioned the country associated with the hospital or clinic brand (which indicated a predominance of physicians or dentists from their country), and its reputation. The location of the institution was not relevant, as far as based in Dubai, instead of another emirate. Some expatriates interviewed could afford to go back to their home country for annual checkups, for a second opinion on a diagnosis, surgery or even for treatments.

Interviewees raised difficulties understanding the meaning of healthcare providers and described their first experience with dentists, mainly because dental services were cheaper in Dubai than in their home country.

Participants emphasized a concern with culture proximity; the importance of being able to communicate, being able to make themselves understood, and to understand the physician or dentist’s diagnosis and treatment recommendation. Interviewees indicated a preference for professionals from Western European countries and the UK.

Based on the literature review, we classified physicians’ nationality, institution where they got their degree and the country associated with the hospital or clinic brand under the COO construct.

This exploratory phase of the study showed that COO was the most relevant factor when selecting a healthcare service provider. It also demonstrated a lack of clarity over the term “healthcare providers”, which according to the OECD, Eurostat and World Health Organization definition “encompass organizations and actors that deliver healthcare goods and services as their primary activity, as well as those for which healthcare provision is only one among a number of activities” (OECD and Eurostat and World Health Organization Citation2017). Given the difficulty interviewees expressed to understand the term “healthcare provider”, we referred to the category as “doctor or dentist” in the following step of this research.

The second stage of the study was a survey using a self-administered online questionnaire through a snowball technique. We developed the questionnaire in accordance with the literature review and the findings of the face-to-face in-depth interviews. There was a filter question we asked respondents: Do you remember your first visit to a physician or dentist in Dubai? For hypothesis 1, a question required respondents to indicate how they found out about that physician or dentist from the options: online research for verification on virtual word of mouth (Parry, Kawakami, and Kishiya Citation2012), and company, a friend or doctor referral for Input WOM (Hugstad, Taylor, and Bruce Citation1987, Hill Citation1988, Webster, 1988, Herr, Kardes, and Kim Citation1991) and “others” which should be followed by a clarification. For hypotheses 2a, 2b, 3 and 4, respondents were asked to select the top-three reasons they chose a particular physician or dentist. The alternatives were inspired by the literature review and the face-to-face questions regarding location (Burge et al. Citation2004; Wun et al. Citation2010; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012; Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017); the reputation of the hospital/clinic (Burge et al. Citation2004; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017, Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017); where they got their degree and residency (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012); years of experience, nationality of the physician or dentist, if the physician/dentist is from the same country as that of the patient, the country of reference of the hospital or clinic (e.g., American Clinic) and demographic questions on gender, age, years of residency in Dubai, education, and nationality(ies).

Because of the nationality diversity of the sample and different levels of English fluency, we conducted a pilot survey to assess questionnaire misunderstandings. The result of the pilot test indicated the need for minor adjustments. The final online version was answered by 372 respondents, of which 364 questionnaires were valid.

Results

presents the exploratory statistics for the two cues: Word-of-Mouth (WOM), Country of Origin (COO), and the other factors found in the literature review concerning patients’ healthcare provider decision process.

Table 1. Exploratory Statistics for Word-of-Mouth (WOM), Country of Origin (COO) and other factors considered when selecting a healthcare provider.

By analyzing WOM, most expatriates interviewed indicated that this factor is important to select a healthcare provider (80%) and the proportion shows the statistical relevance to WOM in selecting a healthcare provider. The most cited item by expatriates as a reference for WOM are friends (62.64%). Besides friends, organizations, family members and other physicians were also statistically relevant items for WOM, as depicted in . A social media community was the least mentioned item and cannot be considered relevant for WOM. To compare the importance of WOM and the other factors when selecting the healthcare provider, a comparison test of the proportions of the two factors was performed. In the sample, almost twice as many expatriates cited the WOM factor as important, compared to COO (the second most cited factor). H1 was confirmed as input personal WOM was the most important in expatriates’ decision process. The difference between WOM and COO reaches 40%, which is statistically relevant with a 95% confidence (Z-statistic = 10.83 and p-value < 0.001).

In the total sample (n = 364), almost 41 percent cited COO as a factor considered when deciding on the healthcare provider, including the nationality of the professional and the country of reference of the hospital or clinic. Using a statistical proportion test, we conclude COO factor is statistically relevant to select a healthcare provider for expatriates. However, comparing COO with other factors, we concluded with a 95% confidence that this factor is not more important than the other factors considered (location, organization reputation, years of experience and institution where physicians got their degree), so H2a was not confirmed (Z-statistic = 1.45 and p-value = 0.0735).

Among the items related to COO, the most cited was the nationality of the physician/dentist (20.88%), followed by the country of reference of the hospital or clinic (13.46%) and whether the physician/dentist is from the same country as that of the patient (12.64%). All these items are considered statistically relevant when choosing the healthcare provider for expatriates, with a 95% confidence, as demonstrated by the proportion tests in . Descriptively, H2b was not confirmed, since a higher percentage of expatriates cited as important the nationality of the physician/dentist (20.88%) whereas only 12.64% indicated the importance of the physician/dentist being from the same country as that of the expatriate. A comparison test of these proportions shows that the percentage of the importance of having the same nationality as that of the patient is less than the nationality of the physician/dentist (Z-statistic = 3.24 and p-value = 0.001), leading to the non-confirmation of H2b. The absence of an intersection between the intervals can confirm the result with a 95% confidence for both proportions ().

Among the other factors listed in the literature, the reputation of the organization was the most cited (40%), after the location of the clinic/physician (35%), and the least mentioned factors were the physician’s years of experience (18%) and the institution where physician got their degree (19%). All these factors were statistically relevant with a 95% confidence.

Expatriates in a new market value WOM from a close credible source (i.e., friends) more than the country of origin. Yet, in a new market, except for the institution where the physician or dentist got their degree, expatriates attribute more importance to COO than to traditional aspects as the reputation of the institution or its location.

In , we present the exploratory statistics for COO and WOM for the total sample and segregated by gender, years of residency in Dubai, age, education level, English proficiency of respondents, and developed or emerging countries. The sample’s age, education, and nationality(ies) distribution correspond to the objectives of researching cross-cultural expatriates covered by medical insurance from developed (46%) and emerging countries (54%). Thirty-five percent of the sample was from Europe, with a predominance of British (13%), 15% were from India and Pakistan, 7% from other Asian countries, 20% from Latin America, 10% from North and Central America, 10% from the Middle East and North Africa, 2% from Australia and Oceania and 1% from Sub-Saharan Africa.

Table 2. Exploratory Statistics for Country of Origin (COO) and Word-of-Mouth (WOM) by gender, years of residency in Dubai, age, education level, English proficiency and expatriates’ nationality (emerging or developed country).

Regarding respondents’ education level, 43 percent have a graduate degree and 41 percent a bachelor’s degree, thus confirming the stereotype that corporate expatriation involves high-flying professionals. In the sample, 75 percent are female, 41 percent are between 35 and 44 years old, and most of them have been in Dubai for over 10 years (33%). The gender distribution of the sample is quite the opposite of that of the UAE in 2020, which was 69% male and 31% female (Dubai Online, Citation2021).

By analyzing the level of English proficiency, we found that 30 percent have a basic level, 27 percent an intermediate level, 18 percent are proficient, and 25 percent are native speakers.

By assessing the importance of the COO factor when selecting the healthcare provider, there is no statistical difference by gender, neither age, nor educational level. Regarding the years of residency in Dubai, those who have been in Dubai for a short period of time give greater importance to COO (Z-score = 6.28 and p-value < 0.05), about 51% of those who have been in the city for less than three years and 42% of those who have lived in the city between three and five years. In the last years, the search tools have improved their quality in terms of speed, content coverage, and credibility checks. It is becoming more common for consumers to verify, online, the education, years of experience, other patient’s reviews, and information on the background of a healthcare provider.

Expatriates who are English native speakers give less importance to COO than those interviewed with other English proficiencies (Z-score = 9.98 and p-value < 0.05). Only 30% of English native speakers said COO is important in selecting the healthcare provider, in comparison with 49% of those with low English level. In this way, H4 is confirmed. Although Arabic is the official language in the emirate, all road and traffic signs and official information on government websites are in Arabic and English, and speaking Arabic is not a requirement for applying for jobs including in the healthcare system, whereas English is a must. Therefore, expatriates with low English proficiency give more importance to COO than native speakers.

For the importance of the WOM factor in the selection of the healthcare provider, there is no relevant difference across education levels. Comparing genders, WOM is more important for women (82.72) than men (71.74), with a statistically significant difference. The result is aligned with Duran, Cetindere Filiz, and Cetindere (Citation2016) that women are more susceptible to WOM than men regarding healthcare services and that, when asking for advice, patients will prioritize friends.

Most expatriates who have been in Dubai for over 10 years consider WOM an important factor (almost 92%), a much higher percentage than for other period categories in Dubai. Ten years ago, search tools and the information available were not as reliable as in recent years. That might explain the predominance of WOM among residents who lived in Dubai for over ten years. In addition, the older the person is, the more relevant is the importance given to WOM (86% of expatriates over 44 years old) and the lower the English proficiency, the more important is WOM (above 80% for basic and intermediate English levels).

Concerning countries’ development, the importance of the country of origin (COO) in choosing a physician is approximately the same for individuals from emerging countries (41%) and from developed countries (40%). The proportion test indicates that there is no significant difference between these percentages, thus not confirming H3. Regarding WOM, individuals from emerging countries give more importance to WOM when selecting a physician than those from developed countries, 85% against 74%. The developing countries represented in the study coincide with the countries classified as collectivist societies by Hofstede’s six-dimension national culture index (Hofstede Citation2013). The results strengthen previous studies that showed a prevalence of WOM in collectivist cultures over individualist ones (Madupu and Cooley Citation2010; Dang and Raska Citation2021).

Discussion

This study contributes to the literature of COO, WOM, expatriate adaptation and selection of health care provider in a number of ways. It is the first research on the decision process of a cross-cultural expatriate sample seeking information on healthcare providers, and it is a pioneering study of this kind carried out in Dubai.

The number of expatriates will continue growing and investigating their behavior is valuable for companies in Dubai and in other cities and countries of the globe that will host international residents. Besides, this paper discusses patients’ behavior concerning COO in terms of branding and nationality of the doctor/dentist. This paper adds to understanding expatriates’ consumer behavior in four crucial dimensions.

First, it shows that personal WOM plays an important role as a cue on expatriate patients’ decision process when seeking information on options available and, depending on the credibility of the source, it supports the selection process. The results confirm previous research that showed WOM is especially important for high involvement services whose outcome involves risk and uncertainty (File, Cermak, and Prince Citation1994; File, Judd, and Prince Citation1992, Ferguson, Paulin, and Leiriao Citation2006). However, for expatriates, contrary to the conclusion of previous studies on regular patients’ decision process (Bornstein, Marcus, and Cassidy Citation2000; Burge et al. Citation2004; Wun et al. Citation2010; Abraham et al. Citation2011; Victoor et al. Citation2012; Greenhalgh et al. Citation2017, Kim, Bae, and Lee Citation2017), the WOM cue is more relevant than the topmost common factors, i.e., location and the reputation of the professional and/or hospital/clinic. Moreover, expatriates consider the reputation of the source of the information, who is commonly a friend, more important than all other factors considered in the decision process, including the reputation of the institution. The results also indicated that WOM’s effect was more pronounced on participants from developing countries.

A second contribution relies on understanding the peculiarities of WOM for expatriate patients. The impact of eWOM through blogs, social media, and online communities on consumers’ attitudes, organization’s reputation, and sales performance has been increasing its influence on consumers’ decisions. Scholars have been studying its reflection on hotels, restaurants, and other service categories (Ye et al. Citation2009, Luca Citation2016). However, even though patients can have easy online access to institutions, brands, and other patients’ reviews to compare alternatives and select which ones best fit the patients’ requirements, this study indicates eWOM has an insignificant impact on expatriates’ healthcare-related decision process.

This paper also adds to the field of promotional tool studies on healthcare institutions’ communication strategies. Previous research refers to existing alternatives: hospital quality reports or the institution website (Gruca and Wakefield Citation2004); online advertising (digital advertising, social media, and website/SEO vendors) and traditional advertising (i.e., print advertising, out-of-home advertising, and in-office) (Antonacci et al. Citation2021); and public relations (Elrod and Fortenberry Citation2020). Even though those sources of information were not mentioned as relevant to expatriates’ decision process, they should not be neglected. Nevertheless, the importance expatriates attributed to personal WOM indicates that healthcare institutions should take actions to promote positive WOM. In order to have more chances to be referred, healthcare providers should offer services that exceed or at least fulfill patients’ expectations. To do so, it is crucial that organizations understand the attributes patients value most throughout their customer journey to assure they will have their expectations concerning those attributes fulfilled. Patients’ journeys should be mapped in three phases: before, during, and after the service. The first starts when patients look for information on the website or contact the institution to make an appointment, progressing through confirmation with directions to the institution and instructions for the consultation and a reminder on the appointment a few days before. The second phase includes the arrival at the institution; the filling of forms; the consultation, exam or procedure; and the departure from the healthcare facility. In the final phase, the institution should execute a post-service satisfaction research. That last step will be critical to identify gaps or service failures that need to be addressed.

The fourth contribution concerns COO. In line with previous studies (Eroglu and Machleit Citation1989; Şekercan et al. Citation2015), this research confirms that COO is a factor supporting expatriates to decide on a health care provider. An additional contribution of this paper is that it sheds light on expatriates’ understanding of the COO components related to healthcare providers - the nationality of the professional and the nation brand associated with the hospital or clinic they work for. Expatriates from countries with moderate to low proficiency in English are the most sensitive to the professional nationality and the nation brand associated with the institution. That suggests an opportunity to be explored by healthcare institutions in markets with a significant presence of expatriates originating from emerging countries and with less English proficiency.

We identified possibilities for further studies on decision-making process related to healthcare providers involving specific situations. This study does not take into account differences among specialties of health services (i.e., primary care, ophthalmology, pediatric, cardiology, trauma and injury, neonatal, etc.). The outcome might be different for sensitive specializations such as a dental implant, surgery, or oncology.

This study did not consider the circumstances that created the need for routine checkups, chronic illnesses, or disabilities. The results can vary depending on the sensitiveness of the situation.

This paper was limited to a high involvement service category. We recommend additional investigation on expatriates’ decision process to such other service as banking and education where global brands operate and WOM and COO might have a different impact.

Lastly, it would be valuable to investigate expatriates’ behavior in other cities with a significant number of expatriates (e.g., Singapore, Toronto, Berlin, and Amsterdam) to identify commonalities and differences across geographies on the topics covered in this study.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Valeria L. M. A. Freundt

Valeria Freundt is a lecturer and a consultant. She teaches undergraduate, graduate and executive-level courses in business and management. She holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration from USP São Paulo, an MBA degree in marketing from COPPEAD/UFRJ and attended the Wharton Business School and Harvard University. Her research interests include brand trust, online & offline marketing communication measures, expatriates’ behavior, nation brand and sustainability. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3699-8442.

Adriana Bruscato Bortoluzzo

Adriana Bortoluzzo is an associate professor at Insper and a consultant. She teaches Statistics topics, such as econometrics, time series, multivariate analysis, and quantitative methods. She holds a Ph.D. in Statistics from USP São Paulo. Her research interests include asset and derivative pricing, corporate finance, portfolio management and corporate governance, as well as marketing strategy. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2872-031X.

References

- Aaker, D. A. 1991. 2009. Managing brand equity: Capitalizing on the value of a brand name. New York: Free Press; Toronto.

- Abraham, J., B. Sick, J. Anderson, A. Berg, C. Dehmer, and A. Tufano. 2011. Selecting a provider: What factors influence patients’ decision making? Journal of Healthcare Management/American College of Healthcare Executives 56 (2):99–116. doi: 10.1097/00115514-201103000-00005.

- Aichner, T. 2014. Country-of-origin marketing: A list of typical strategies with examples. Journal of Brand Management 21 (1):81–93. doi: 10.1057/bm.2013.24.

- Amine, L. S., and S.-H. Shin. 2002. A comparison of consumer nationality as a determinant of COO preferences. Multinational Business Review 10 (1):45–53.

- Andresen, M., F. Bergdolt, J. Margenfeld, and M. Dickmann. 2014. Addressing international mobility confusion – Developing definitions and differentiations for self-initiated and assigned expatriates as well as migrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (16):2295–318. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.877058.

- Antonacci, C. L., A. M. Omari, R. Bassora, H. B. Levine, A. Seidenstein, G. R. Klein, C. Inzerillo, F. G. Alberta, and S. Sodha. 2021. Success of various marketing strategies for a new-to-the-area orthopedic practice. Cureus 13 (9):1–6. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18122.

- Arndt, J. 1967. Role of product-related conversations in the diffusion of a new product. Journal of Marketing Research 4 (3):291–5. doi: 10.2307/3149462.

- Batra, R., V. Ramaswamy, D. L. Alden, J.-B E. M. Steenkamp, and S. Ramachander. 2000. Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries. Journal of Consumer Psychology 9 (2):83–95. doi: 10.1207/15327660051044178.

- Berentzen, J. B., C. Backhaus, M. Michaelis, M. Blut, D. Ahlert. 2008. Does ‘Made In …’ also apply to services? An empirical assessment of the country-of-origin effect in service settings. Journal of Relationship Marketing 7 (4):391–405. doi: 10.1080/15332660802508364.

- Bilkey, W. J., and E. Nes. 1982. Country-of-origin effects on product evaluations. Journal of International Business Studies 13 (1):89–100. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490539.

- Bornstein, B. H., D. Marcus, and W. Cassidy. 2000. Choosing a doctor: An exploratory study of factors influencing patients’ choice of a primary care doctor. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 6 (3):255–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00256.x.

- Brown, H. D., ed. 2014. Principles of language learning and teaching. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

- Brown, J. D., R. L. Collins, and G. W. Schmidt. 1988. Self-esteem and direct versus indirect forms of self-enhancement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 55 (3):445–53. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.55.3.445.

- Brown, J. J., and P. H. Reingen. 1987. Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research 14 (3):350. doi: 10.1086/209118.

- Burge, P., N. Devlin, J. Appleby, C. Rohr, and J. Grant. 2004. Do Patients Always Prefer Quicker Treatment?: a discrete choice analysis of patients’ stated preferences in the London Patient Choice Project. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 3 (4):183–94. doi: 10.2165/00148365-200403040-00002.

- Buttle, F. A. 1998. Word of mouth: Understanding and managing referral marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing 6 (3):241–54. doi: 10.1080/096525498346658.

- Caligiuri, P., J. Phillips, M. Lazarova, I. Tarique, and P. Burgi. 2001. The theory of met expectations applied to expatriate adjustment: The role of cross-cultural training. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 12 (3):357–72. doi: 10.1080/09585190121711.

- Cerdin, J.-L., and J. Selmer. 2014. Who is a self-initiated expatriate? Towards conceptual clarity of a common notion. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (9):1281–301. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2013.863793.

- Cilingir, Z., and C. Basfirinci. 2014. The impact of consumer ethnocentrism, product involvement, and product knowledge on country of origin effects: an empirical analysis on Turkish consumers’ product evaluation. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 26 (4):284–310. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2014.916189.

- Costa, C., J. Carneiro, and R. Goldszmidt. 2016. Country image effect on product assessment: Moderating role of consumer nationality. Review of Business Management 18 (59):24–42. doi: 10.7819/rbgn.v18i59.2474.

- Curasi, C. F., and K. Norman Kennedy. 2002. From prisoners to apostles: A typology of repeat buyers and loyal customers in service businesses. Journal of Services Marketing 16 (4):322–41. doi: 10.1108/08876040210433220.

- Dang, A., and D. Raska. 2021. National cultures and their impact on electronic word of mouth: A systematic review. International Marketing Review. doi: 10.1108/IMR-12-2020-0316.

- De Angelis, M., A. Bonezzi, A. M. Peluso, D. D. Rucker, and M. Costabile. 2012. On braggarts and gossips: A self-enhancement account of word-of-mouth generation and transmission. Journal of Marketing Research 49 (4):551–63. doi: 10.1509/jmr.11.0136.

- Dixon, A., R. Robertson, J. Appleby, P. Burge, N. Devlin, and H. Magee. 2010. Patient choice how patients choose and how providers respond. The King’s Fund. http://hrep.lshtm.ac.uk/publications/Dixon%20Summary%20Final.pdf.

- Dubai Health Authority. 2019. A comprehensive guide on health investment in Dubai with a listing of investment needs and opportunities for health services. https://www.dha.gov.ae/Asset%20Library/27012019/eng.pdf

- Dubai Online. 2021. “UAE Population Statistics 2020 - Total, Nationality, Migrants, Gender.” Dubai Online. 2021. https://www.dubai-online.com/essential/uae-population-and-demographics/.

- Dubai Statistics Center (DSC). 2020. “Population Bulletin Emirate of Dubai 2020.” Accessed September 17, 2021. https://www.dsc.gov.ae/Publication/Population%20Bulletin%20Emirate%20of%20Dubai%20%20-%202020.docx.

- Dubois, D., A. Bonezzi, and M. De Angelis. 2016. Sharing with friends versus strangers: How interpersonal closeness influences word-of-mouth valence. Journal of Marketing Research 53 (5):712–27. doi: 10.1509/jmr.13.0312.

- Duhan, D. F., S. D. Johnson, J. B. Wilcox, and G. D. Harrell. 1997. Influences on consumer use of word-of-mouth recommendation sources. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 25 (4):283–95. doi: 10.1177/0092070397254001.

- Duran, C., A. Cetindere Filiz, and A. Cetindere. 2016. Word of mouth marketing: An empirical investigation in healthcare services. Pressacademia 3 (3):232. doi: 10.17261/Pressacademia.2016321980.

- EF International Language Centers. 2020. “EF EPI 2020 - EF English Proficiency Index.” Ef.com. 2020. https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/.

- Elrod, J. K., and J. L. Fortenberry. 2020. Public relations in health and medicine: Using publicity and other unpaid promotional methods to engage audiences. BMC Health Services Research 20 (S1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05602-x.

- Engel, J. F., R. J. Kegerreis, and R. D. Blackwell. 1969. Word-of-mouth communication by the innovator. Journal of Marketing 33 (3):15–19. doi: 10.2307/1248475.

- Erickson, G. M., R. Jacobson, and J. K. Johansson. 1992. Competition for market share in the presence of strategic invisible assets: The US automobile market, 1971–1981. International Journal of Research in Marketing 9 (1):23–37. doi: 10.1016/0167-8116(92)90027-I.

- Eroglu, S. A., and K. A. Machleit. 1989. Effects of individual and product‐specific variables on utilising country of origin as a product quality cue. International Marketing Review 6 (6):27–41. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000001525.

- Farcas, D., and M. Gonçalves. 2017. Motivations and cross-cultural adaptation of self-initiated expatriates, assigned expatriates, and immigrant workers: The case of Portuguese migrant workers in the United Kingdom. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 48 (7):1028–51. doi: 10.1177/0022022117717031.

- Feldman, S. P., and M. C. Spencer. 1965. The effect of personal influence in the selection of consumer services. In Proceedings of the Fall Conference of the American Marketing Association, 440–52. Chicago: Peter D. Bennett.

- Ferguson, R. J., M. Paulin, and E. Leiriao. 2006. Loyalty and Positive word-of-mouth: patients and hospital personnel as advocates of a customer-centric health care organization. Health Marketing Quarterly 23 (3):59–77. doi: 10.1080/07359680802086174.

- File, K. M., B. B. Judd, and R. A. Prince. 1992. Interactive marketing: The influence of participation on positive word‐of‐mouth and referrals. Journal of Services Marketing 6 (4):5–14. doi: 10.1108/08876049210037113.

- File, K. M., D. S. P. Cermak, and R. A. Prince. 1994. Word-of-mouth effects in professional services buyer behaviour. The Service Industries Journal 14 (3):301–14. doi: 10.1080/02642069400000035.

- Gaedeke, R. 1973. Consumer attitudes toward products ‘Made In’ developing countries. Journal of Retailing 49 (2):13–24.

- Goodrich, K., and M. de Mooij. 2014. How ‘social’ are social media? A cross-cultural comparison of online and offline purchase decision influences. Journal of Marketing Communications 20 (1–2):103–16. doi: 10.1080/13527266.2013.797773.

- Greenhalgh, J., S. Dalkin, K. Gooding, E. Gibbons, J. Wright, D. Meads, N. Black, J. M. Valderas, and R. Pawson. 2017. Functionality and feedback: A realist synthesis of the collation, interpretation and utilisation of patient-reported outcome measures data to improve patient care. Health Services and Delivery Research 5 (2):1–280. doi: 10.3310/hsdr05020.

- Gruca, T. S., and D. S. Wakefield. 2004. Hospital web sites: Promise and progress. Journal of Business Research 57 (9):1021–25. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00349-1.

- Gudykunst, W. B. 1985. A model of uncertainty reduction in intercultural encounters. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 4 (2):79–98. doi: 10.1177/0261927X8500400201.

- Gürhan-Canli, Z., and D. Maheswaran. 2000. Determinants of country-of-origin evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research 27 (1):96–108. doi: 10.1086/314311.

- Hennig-Thurau, T., K. P. Gwinner, G. Walsh, and D. D. Gremler. 2004. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? Journal of Interactive Marketing 18 (1):38–52. doi: 10.1002/dir.10073.

- Herr, P. M., F. R. Kardes, and J. Kim. 1991. Effects of word-of-mouth and product-attribute information on persuasion: An accessibility-diagnosticity perspective. Journal of Consumer Research 17 (4):454. doi: 10.1086/208570.

- Hill, J. C. 1988. Differences in the Consumer Decision Process for Professional vs. Generic Services. Journal of Services Marketing 2 (1):17–23. doi: 10.1108/eb024712.

- Hofstede, G. 2013. The 6 Dimensions Model of National Culture by Geert Hofstede. Geert Hofstede. 2013. https://geerthofstede.com/culture-geert-hofstede-gert-jan-hofstede/6d-model-of-national-culture/.

- Hsieh, M.-h. 2004. An investigation of country-of-origin effect using correspondence analysis: a cross-national context. International Journal of Market Research 46 (3):267–95. doi: 10.1177/147078530404600302.

- Hugstad, P., J. W. Taylor, and G. D. Bruce. 1987. The effects of social class and perceived risk on consumer information search. Journal of Consumer Marketing 4 (2):41–46. doi: 10.1108/eb008195.

- IndexMundi. 2021. “United Arab Emirates Demographics Profile.” https://www.indexmundi.com/united_arab_emirates/demographics_profile.html

- InterNations. 2021. “Expat City Ranking.” InterNations. https://cms-internationsgmbh.netdnassl.com/cdn/file/cms-media/public/2021-11/Expat-Insider_City-Ranking-Report-2021_1.pdf

- International Insurance. 2021. Understanding Dubai’s Healthcare System. International Citizens Insurance. https://www.internationalinsurance.com/health/systems/dubai.php

- International Monetary Fund. 2021. World Economic Outlook Database April 2020 – WEO groups and aggregates information. http://www.imf.org. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2021/01/weodata/groups.htm

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2018. “WORLD MIGRATION REPORT 2018.” https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2018_en.pdf.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2020. “World migration report 2020.” https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf.

- Kang, S.-M. 2006. Measurement of acculturation, scale formats, and language competence. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 37 (6):669–93. doi: 10.1177/0022022106292077.

- Keller, K. L. 1993. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing 57 (1):1–22. doi: 10.2307/1252054.

- Kim, Y.-Y., J. Bae, and J.-S. Lee. 2017. Effects of patients’ motives in choosing a provider on determining the type of medical institution. Patient Prefer Adherence 11:1933–38. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S148530.

- Koubaa, Y., R. Boudali Methamem, and F. Fort. 2015. Multidimensional structures of brand and country images, and their effects on product evaluation. International Journal of Market Research 57 (1):95–124. doi: 10.2501/IJMR-2015-007.

- Lee, J. K., and W.-N. Lee. 2009. Country-of-origin effects on consumer product evaluation and purchase intention: The role of objective versus subjective knowledge. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 21 (2):137–51. doi: 10.1080/08961530802153722.

- Lovett, M. J., R. Peres, and R. Shachar. 2013. On brands and word of mouth. Journal of Marketing Research 50 (4):427–44. doi: 10.1509/jmr.11.0458.

- Lu, N., and H. Wu. 2016. Exploring the impact of word-of-mouth about physicians’ service quality on patient choice based on online health communities. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 16 (1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12911-016-0386-0.

- Luca, M. 2016. Reviews, reputation, and revenue: The case of yelp.com. Harvard Business School NOMUnit Working Paper No. 12-016. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.1928601.

- Madupu, V., and D. O. Cooley. 2010. Cross-cultural differences in online brand communities: an exploratory study of Indian and American online brand communities. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 22 (4):363–75. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2010.505886.

- Maheswaran, D. 1994. Country of origin as a stereotype: Effects of consumer expertise and attribute strength on product evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research 21 (2):354. doi: 10.1086/209403.

- McNulty, Y., and C. Brewster. 2017. Theorizing the meaning(s) of ‘expatriate’: Establishing boundary conditions for business expatriates. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 28 (1):27–61. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2016.1243567.

- Michaelis, M., D. M. Woisetschläger, C. Backhaus, and D. Ahlert. 2008. The effects of country of origin and corporate reputation on initial trust. International Marketing Review 25 (4):404–22. doi: 10.1108/02651330810887468.

- Min Han, C. 1989. Country image: Halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research 26 (2):222–29. doi: 10.2307/3172608.

- Miocevic, D., and S. Zdravkovic. 2020. Expatriate consumers’ adaptations and food brand choices: A compensatory control perspective. Journal of International Marketing 28 (4):75–89. doi: 10.1177/1069031X20961112.

- Mort, G. S., M. Duncan. 2003. Owned by …’: country of origin’s new cue. Journal of International Consumer Marketing 15 (3):49–69. doi: 10.1300/J046v15n03_04.

- Murray, K. B. 1991. A test of services marketing theory: Consumer information acquisition activities. Journal of Marketing 55 (1):10–25. doi: 10.2307/1252200.

- Nagashima, A. 1970. A comparison of Japanese and U.S. attitudes toward foreign products. The International Executive 12 (3):7–8. doi: 10.1002/tie.5060120304.

- OECD, Eurostat and World Health Organization. 2017. Classification of health care providers (ICHA-HP) in a system of health accounts 2011: Revised Edition. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi: 10.1787/9789264270985-en..

- Pappu, R., P. G. Quester, and R. W. Cooksey. 2007. Country image and consumer-based brand equity: Relationships and implications for international marketing. Journal of International Business Studies 38 (5):726–45. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400293.

- Parry, M. E., T. Kawakami, and K. Kishiya. 2012. The effect of personal and virtual word-of-mouth on technology acceptance. Journal of Product Innovation Management 29 (6):952–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00972.x.

- Paswan, A. K., and D. Sharma. 2004. Brand‐Country of Origin (COO) knowledge and COO image: investigation in an emerging franchise market. Journal of Product & Brand Management 13 (3):144–55. doi: 10.1108/10610420410538041.

- Petty, R. E., J. T. Cacioppo, and D. Schumann. 1983. Central and peripheral routes to advertising effectiveness: The moderating role of involvement. Journal of Consumer Research 10 (2):135. doi: 10.1086/208954.

- Relerson, C. 1966. Are foreign products seen as national stereotypes? Journal of Retailing 42 (3):33.

- Roth, M. S., and J. B. Romeo. 1992. Matching product category and country image perceptions: A framework for managing country-of-origin effects. Journal of International Business Studies 23 (3):477–97. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490276.

- Ryu, G., J. Park, and L. Feick. 2006. The role of product type and country-of-origin in decisions about choice of endorser ethnicity in advertising. Psychology and Marketing 23 (6):487–513. doi: 10.1002/mar.20131.

- Schooler, R. D. 1966. Product bias in the central American common market. The International Executive 8 (2):18–19. doi: 10.1002/tie.5060080211.

- Seidlhofer, B. 2001. Closing a conceptual gap: The case for a description of English as a Lingua Franca. International Journal of Applied Linguistics 11 (2):133–58. doi: 10.1111/1473-4192.00011.

- Şekercan, A., M. Lamkaddem, M. B. Snijder, R. J. G. Peters, and M. Essink-Bot. 2015. Healthcare consumption by ethnic minority people in their country of origin and the relation with migration generation. European Journal of Public Health 25 (suppl_3):384–390. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckv167.010.

- Selmer, J. 2006. Language ability and adjustment: Western expatriates in China. Thunderbird International Business Review 48 (3):347–68. doi: 10.1002/tie.20099.

- Shaffer, M. A., D. A. Harrison, and K. M. Gilley. 1999. Dimensions, determinants, and differences in the expatriate adjustment process. Journal of International Business Studies 30 (3):557–81. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490083.

- Sharma, P. 2011. Country of origin effects in developed and emerging markets: Exploring the contrasting roles of materialism and value consciousness. Journal of International Business Studies 42 (2):285–306. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2010.16.

- Sheth, J. N. 2011. Impact of emerging markets on marketing: Rethinking existing perspectives and practices. Journal of Marketing 75 (4):166–82. doi: 10.1509/jmkg.75.4.166.

- Steenkamp, J.-B E. M. 2019. Global versus local consumer culture: Theory, measurement, and future research directions. Journal of International Marketing 27 (1):1–19. doi: 10.1177/1069031X18811289.

- Tang, L. 2017. Mine your customers or mine your business: The moderating role of culture in online word-of-mouth reviews. Journal of International Marketing 25 (2):88–110. doi: 10.1509/jim.16.0030.

- Victoor, A., R. D. Friele, D. M. J. Delnoij, and J. J. D. J. M. Rademakers. 2012. Free choice of healthcare providers in the Netherlands is both a goal in itself and a precondition: Modelling the policy assumptions underlying the promotion of patient choice through documentary analysis and interviews. BMC Health Services Research 12 (1):441. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-441.

- Wun, Y. T., T. P. Lam, K. F. Lam, D. Goldberg, D. K. T. Li, and K. C. Yip. 2010. How do patients choose their doctors for primary care in a free market? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 16 (6):1215–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01297.x.

- Ye, Q., R. Law, and B. Gu. 2009. The impact of online user reviews on hotel room sales.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 28 (1):180–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2008.06.011.

- Yellow Pages United Arab Emirates. 2021. “Dubai in UAE on Yellow Pages, UAE.” www.yellowpages-Uae.com. 2021. https://www.yellowpages-uae.com/uae/dubai.

- Zeithaml, V. A. 1981. How consumer evaluation processes differ between goods and services. Marketing of Services 9 (1):25–32.

- Zeithaml, V. A., A. Parasuraman, and L. L. Berry. 1985. Problems and strategies in services marketing. Journal of Marketing 49 (2):33–46. doi: 10.2307/1251563.