Abstract

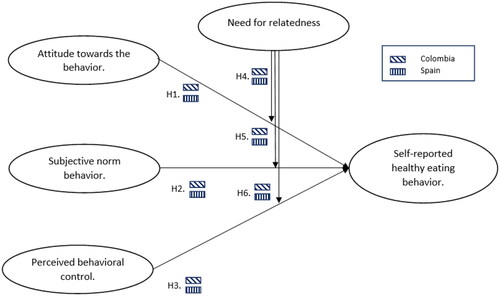

This research analyses the moderating effects of the need for relatedness in the relationship between behavioral intention (attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm behavior, and perceived behavioral control) and self-reported healthy eating behavior in millennials. A structural equation model was used in a sample of 2380 young people (25–35 years old) in Colombia and Spain (1190 for each country) considered healthy-food consumers. The results show that both attitudes toward the behavior and subjective norm behavior positively influence self-reported healthy eating behavior. In contrast, perceived control behavior does not affect self-reported healthy eating behavior. The need for relatedness moderates the relationship between behavioral intention and self-reported healthy eating behavior. The results suggest that the isolation conditions caused by the pandemic directly affect the behavior of millennials regarding the consumption of healthy food. This pandemic condition affects their lifestyles and preferences associated with consumption.

Introduction

Millennials today receive considerable attention as a market with important consumer characteristics for today’s economies (Kymäläinen, Seisto, & Malila, Citation2021). This population was born after 1982 and represented a large portion of the current market. Some research suggests that recent behavioral changes may be due to concern about environmental changes and their impact on people’s daily lives (The Food Standards Agency, Citation2019). The millennial generation grew up immersed in various societal changes; they are characterized by valuing individuality, and personal and environmental care prevails. They take responsibility for their diet and their health, which can be healthy or harmful their health, which can be healthy or harmful.

Millennials have synthesized the main attributes that define this generation: high exposure to technology and information, intensive use of social networks, multiplatform and multitasking behavior, the need for socialization, empowerment, low permeability to traditional media, a demanding character in the face of brands and an individualistic personality (Escandon-Barbosa et al., Citation2020). Their main types of communication have been synthesized to generate effective brand strategies in social networks, including multiplatform communication, empathic language, relevant content, authenticity and honesty, the use of word of mouth, communication aligned with the values of the generation, valuing superior brands, active participation, content in an audio-visual format and reward strategies (Cartagena, Citation2017; Ateş, Demir Özdenk, & Çaliskan, Citation2021).

Millennials show a high level of involvement in everything related to food. For this generation, a meal is not simply a measure of saturation but also an opportunity for self-expression and new experiences (Morrison, Citation2019). In addition, food brings people together in a physical space, which is especially vital in the era of high digitization (Pinsker, Citation2001). Therefore, it is established that food continues to be a unifying factor that may still be used to express and bring together the millennial generation. In this sense, food assumes a character that extends above its function as a means of satisfying a need to include a setting for social interaction and a lifestyle.

Despite cultural changes and different fashions, this generation shows a demanding character concerning their diet. Although some have an unhealthy diet, the vast majority show concern about what they eat and are aware of the food they consume (Lai, Chang, Lee, & Liao, Citation2021).

The present study considers three gaps in the literature. The first is related to the need to use other constructs as well as other theories that complement the approaches of the theory of planned behavior, especially about intentions (Ateş, Demir Özdenk, & Çaliskan, Citation2021). Considering the fact that Colombia and Spain have diverse consumption patterns and economic situations while share cultural characteristics that make it possible to identify between them, we chose these two nations as the focus of our research in order to validate the theory.

The second considers the importance of research on consumption patterns in millennials, especially regarding healthy food, from the perspective of the theory of planned behavior (Yazdan-Panah, Komendantova, Shirazi, & Linnerooth-Bayer, Citation2015; Verain, Bouwman, Galama, & Reinders, Citation2022). This last aspect has important implications not only for identifying consumption habits but also as an instrument for the design of public policies. The third gap involves the need to conduct studies of additional variables that allow a broader framework of analysis to be considered. Thus, it is necessary to identify the roles of every variable in the generation of consumption habits (Burton, Citation2004; Hasheminezhad & Yazdan-Panah, Citation2016; Lai, Chang, Lee, & Liao, Citation2021).

The present study is structured as follows. The first part of the document analyses the theories used in the research, such as the theory of planned behavior and self-determination theory. The second part presents the study methodology and an explanation of the variables used and their role in the established model. Finally, the results, conclusions, limitations, and future avenues are presented.

Theoretical Framework

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has been used intensively to understand behavior patterns in the consumption of organic, healthy, and green products (Chaba, Scoffier-Mériaux, d’Arripe-Longueville, & Lentillon-Kaestner, Citation2021; Douglas, Blumenthal, & Guarnaccia, Citation2021; Scalco, Noventa, Sartori, & Ceschi, Citation2017). This theory states that the intention to develop a behavior is the best predictor of an individual’s current behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Three constructs constitute behavioral intention: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm behavior, and perceived behavioral control (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002; Khani Jeihooni, Jormand, Saadat, Hatami, Abdul Manaf, & Afzali Harsini, Citation2021).

Other studies in the field of the theory of planned behavior have focused on different topics, such as healthy consumption habits (Dorce, da Silva, Mauad, Domingues, & Borges, 2021; Imani, Allahyari, Bondori, Surujlal, & Sawicka, Citation2021; Pang, Tan, & Lau, Citation2021), the use of nonrenewable natural resources (Tao, Duan, & Deng, Citation2021), governance (Huang, Aguilar, Yang, Qin, & Wen, Citation2021), the use of renewable energy (Liobikienė, Dagiliūtė, & Juknys, Citation2021), panic buying (Lehberger, Kleih, & Sparke, Citation2021), policy design (Mahdavi, Citation2021) and entrepreneurship (Rueda Barrios, Rodriguez, Plaza, Zapata, & Zuluaga, Citation2021). In the case of healthy consumption, the results have shown that high consumer perception of healthy habits produces environmentally friendly behavior that promotes support for local economies through the production of healthy food (Kushwah, Dhir, Sagar, & Gupta, Citation2019; Massey, O’Cass, & Otahal, Citation2018; Rana & Paul, Citation2017, Citation2020).

The theory of planned behavior has been one of the most frequently used theories to explain the behaviors adopted in pandemic conditions. Various studies have focused on different fields, including health (Miconi et al., Citation2020; Shmueli, Citation2021; Shubayr, Mashyakhy, Al Agili, Albar, & Quadri, Citation2020; Xia, Shi, Chang, Miao, & Wang, Citation2021), public health (Irfan et al., Citation2021), social psychology (Trifiletti, Shamloo, Faccini, & Zaka, Citation2021), tourism (Wang, Jin, Fan, Ju, & Xiao, Citation2021; Tsang et al., Citation2021), food and consumer behavior (Lehberger, Kleih, & Sparke, Citation2021; Sun et al., Citation2021) and the environment (Lucarelli, Mazzoli, & Severini, Citation2020).

On the other hand, in pandemic conditions, the influence of what is perceived as social obligation can be observed on the types of behaviors adopted by individuals. This aspect includes family, friends, and neighbors. Studies using the theory of planned behavior have found influences of social norms on behaviors adopted by individuals (Santana, Fischer, Jaeger, & Wong-Parodi, Citation2020). Finally, concerning perceived behavioral control, the more control individuals feel over risks in pandemic conditions, the more likely they are to adopt behaviors that allow them to respond to the situation (Ahmad, Iram, & Jabeen, Citation2020).

Healthy Attitudes and Behavior

The Theory of Planned Behavior states that some factors at the individual level can influence behavior (Al-Jubari, Citation2019; Chen & Hung, Citation2016; Hsu et al., Citation2017; Paul et al., Citation2016; Sun et al., Citation2021). This concept starts from the premise that behavior is stimulated by intentions summarized in three elements: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm behavior and perceived behavioral control (Deng, Zheng, Lu, Zeng, & Liu, Citation2021). Attitude is understood as a positive or negative evaluation of behavior. Subjective norms refer to the social pressure of individuals who influence the behavior of other individuals. Finally, perceived behavioral control is the perception of the degree of control in contributing to or hindering the development of a particular behavior.

According to Psouni, Hassandra, and Theodorakis (Citation2016), the study of attitudes toward adopting healthy eating behavior is attractive due to the implications for health interventions for specific population segments. According to the literature, there is a need to understand better individuals’ intention to adopt self-reported healthy eating behavior. This would provide tools that allow health professionals hindering unhealthy lifestyles (Bebetsos, Chroni, & Theodorakis, Citation2002; Chen, Lee, & Lu, Citation2021).

In general, attitude toward the behavior is relevant because it can change the possibility of adopting a positive or negative behavior of healthy eating. In this respect, the consumer’s behavior arises from an internal assessment of the benefits of adopting the behavior, which is then translated into implementing that healthy eating behavior. According to Al-Rafee and Cronan (Citation2006), the established attitude toward conduct is still an essential component of social psychology. Similarly, multiple studies have demonstrated that attitude is the strongest predictor of a given behavior. The availability of a penalty or compensation that supports this imagined action will impact this behavior. Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: Attitude toward the behavior positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H1a) Colombia and H1b) Spain.

We attempt to answer a question, especially among health professionals who have not yet obtained conclusive answers. This question is related to adopt self-reported healthy eating behavior and how unsafe habits can be modified, especially in terms of the abuse of substances (e.g., tobacco, alcohol, and drugs) (Moraes, Alvarenga, Moraes, & Cyrillo, Citation2021). The subjective norm is related with more facility to include healthy eating in a daily routine because social pression about healthy behavior can motivate and increase the possibility to develop more self-reported healthy eating behavior in more consumers.

Considering the above, the subjective norms represent the social factors that lead to social pressures for adopting certain behavior. Therefore, the influence of communities or groups can lead to the approval or rejection of food consumption or its adoption (de adoption (de Kervenoael, Schwob, Hasan, & Ting, Citation2021). Another essential aspect to highlight is that, according to the literature in the field, external factors may appear as key factors. According to the literature in the area, external factors may occur in adopting norms that consider self-negotiated standards. This type of adoption can lead individuals to follow norms that modify decision-making mechanisms to do something (Vinnell, Milfont, &McClure, Citation2019). Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Subjective norm behavior positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H2a) Colombia and H2b) Spain.

Regarding millennials, some studies have found that emotional factors have a strong influence on consumption habits, especially in increasing the intake of snacks with elevated levels of energy (Oliver & Wardle, Citation1999; Sims et al., Citation2008, Pang et al., Citation2021). Additionally, Schachter (Citation1971) proposes that external stimuli promote consumption regardless of satisfaction. In previous studies, 50% of the study population showed behavior related to unhealthy acts due to emotional aspects as a defence against external factors that produce dissatisfaction (Nguyen-Rodriguez et al., Citation2008).

In general, perceived control creates the possibility of adopting or not adopting a behavior because the consumer can evaluate restrictions and their effects to remain steadfast in developing a healthy eating behavior. According to La Barbera and Ajzen (Citation2020), the subjective norms of an individual can have a negative impact when assuming a behavior. This approach is because individuals are more influenced by the norms surrounding their actions when they have a high perceived control. Additionally, other research suggests that high levels of perceived control allow acting according to an intention to adopt a healthy behavior.

According to Alkhathami et al. (Citation2021), perceived control represents the ease or difficulty of developing a behavior. The ability to develop a behavior is related to the resources and opportunities that an individual possesses and allows the development of behavior. This behavior is conceived as the result of beliefs determining control over a given behavior. This perceived control also allows the evaluation of the importance of resources and opportunities for developing healthy behavior. Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Perceived behavioral control positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H3a) Colombia and H3b) Spain.

Self-Determination Theory

Self-determination theory suggests three basic needs that every individual needs to satisfy at a certain level: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Autonomy refers to the need to feel that a behavior is a product of self-determination (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985, Citation2002; Moore, Holding, Moore, Levine, Powers, Zuroff, & Koestner, Citation2021; Reis, Sheldon, Gable, Roscoe, & Ryan, Citation2000), competence refers to the feeling of effectiveness and the ability to carry out a task (Harter, Citation1978; Ryan & Deci, Citation2002; White, Citation1959), while relatedness refers to the need to feel connected to, supported by or cared for by other people (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Johnston & Finney, Citation2010; Pitchay, Eliz, Ganesan, Mydin, Ratnasari, & Thaker, Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2002; Sheldon & Niemiec, Citation2006).

Satisfaction or dissatisfaction will be generated over time to the extent that an individual has interaction. A low sense of belonging constitutes a feeling of severe deprivation and is the cause of collateral effects (Yildiz & Kiliç, Citation2021). Therefore, attitude toward a behavior is influenced by emotions and thoughts that are caused by a motive that arises from the need to interact with other individuals and affects self-reported healthy eating behavior (Baumeister & Leary, Citation1995; Jones, Feigenbaum, & Jones, Citation2021). This need for relatedness and feelings of belonging and concern for others influences the relationship between attitude toward behavior and behavior adoption. From a psychological point of view, the feeling of being connected with others through belonging to a group allows the individual to develop more positive attitudes toward adopting healthy behavior patterns (Yushi, Naqvi & Naqvi, Citation2018). In conclusion, a healthy habit will be adopted to the extent that it is reinforced by relationships with other individuals who belong to the same group (Carlton, Garcia, Andino, Ollendick, & Richey, Citation2022).

As a result, satisfying this need will have an impact on self-regulation and, as a result, the adoption of a healthy lifestyle not only physically but also mentally (LaCaille, Hooker, & LaCaille, Citation2020), which will enhance their behavior and, as a result, their choice of behavior. Investigations in the field have revealed that among a part of the population, the relationship between meeting these needs and being concerned about one’s body image and controlling one’s weight is related (LaCaille, Hooker, & LaCaille, Citation2020). Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: The need for relatedness moderates the relation between attitude toward a behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H4a) Colombia and H4b) Spain.

According to the literature, it is pertinent to note that if there is a need for social interaction. This condition will influence the search for the approval of the social group. Belonging becomes a stimulus for the adoption of specific behaviors. This is based on the idea that there is a need to maintain social ties and a degree of intimacy in the set of closest relationships (de Araujo, Citation2021; Johnston & Finney, Citation2010; Peetz & Milyavskaya, Citation2021).

It is precisely in need to maintain social relations that an individual is influenced by group pressures to carry out behaviors following what is accepted by society and to be limited by the social restrictions that the group imposes. According to authors such as Mišovič (Citation2022), there are socially legitimate mechanisms that make people develop conducts that are socially promoted. These behaviors are reinforced by the need to belong to the group, a need that will lead the individual to adopt behaviors more quickly. According to Ryan and Deci (Citation2002), more significant interaction with others generates a sense of self that responds to social pressures more successfully and then self-reported healthy eating behavior. Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5: The need for relatedness moderates the relation between subjective norm behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H5a) Colombia and H5b) Spain.

According to Horney (Citation1945), isolation is considered basic anxiety. Isolation condition generates the sensation of being defenseless in a potentially hostile situation. Therefore, the sense of isolation is a function of belonging to a social group. Such isolation can produce impotence in the individual and generate frustration due to the inability to control a situation (Callea et al., Citation2019). External forces that reinforce an individual’s intrinsic motivations influence the feeling of being in control of behavior. These motivations depend on external criteria that play the role of approving or disapproving of a behavior, in this case, concerning self-reported healthy eating behavior (Deci & Ryan, Citation1985, Citation2002; Freund, & Lohbeck, Citation2020; Ryan & Deci, Citation2002; Xiang, Zhang, Ning, Wu, & Chen, Citation2021; Zhao, Roehrig, Patrick, Levesque-Bristol, & Cotner, Citation2021) For authors such as Maas et al. (Citation2022), the need for relatedness is established as a basic need that involves feelings of connection with others to form interpersonal relationships. The need for relatedness plays a key role in the interaction with others and has become a key condition that allows individuals to develop behaviors in accordance with their abilities and resources.

According to Linos, Jakli, and Carlson (Citation2021), people permanently require to be able to satisfy the need to belong to a group. Therefore their value judgment will be based on the values generated in the group to which they belong. These values adopted by the individual will become a set of conceptions that will determine their behavior and way of seeing life with respect to those not part of their group. Here, social aspects based on promulgated values become control elements that control individual actions. In this way, the perceived behavioral control is reinforced by the need for relatedness in behavior adoption (Chen et al., Citation2021). Following the above, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: The need for relatedness moderates the relation between perceived behavioral control and self-reported healthy eating behavior for: H6a) Colombia and H6b) Spain.

Materials and Methods SEM (Structural Equation Model)

Data

This study used a simple random sample of 2380 young consumers in Colombia and Spain aged 24 to 35 years old. This distribution is according to Colombian population data from the National Administrative Department of Statistics. The response rate was approximately 96%, and the study was conducted through personal interviews in three cities in each country: Bogotá, Cali, Medellín and Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia ().

The choice of the two countries for this study was related to their differences in the parameters of consumption habits. This allowed for an analysis that included different and similar factors between the two objects of study and for consideration of the characteristics of the two countries with different conditions and during a time range such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Although Colombia and Spain are similar, given that they speak the same language, they have cultural dimensions that differentiate them and allow the identification of characteristics related to the cultural dynamics of each country.

It can be observed in the literature that in North America, food consumption patterns have attracted greater attention compared to European countries (Elmadfa, & Meyer, Citation2015). Despite the above, the European Union has institutions in charge of verifying the food conditions that enter the territory. Additionally, these institutions must verify the application of the rules that regulate food consumption. Likewise, the EU has policies that regulate the entry of food according to specifications demanded by the different countries (Pérez-Cueto, Aschemann-Witzel, Shankar, Brambila-Macias, Bech-Larsen, Mazzocchi, & Verbeke, Citation2012).

Model Variables

This model has five constructs with different roles: a dependent construct, a moderation variable, and independent constructs.

Dependent Construct

Self-Reported Healthy Eating Behavior

This concept was the central construct in our model. The items were measured via the Eating Behavior Questionnaire (EBQ; Bebetsos, Theodorakis, Laparidis, & Chroni, Citation2000; Bebetsos et al., Citation2002) with twenty-two items related to healthy food.

Independent Constructs

Considering our theoretical framework, behavioral intention was assessed by three constructs: attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm behavior and perceived behavioral control (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002).

Attitude Toward the Behavior

This construct was measured with six items related to feelings about purchasing this kind of food: interesting, good idea, important, beneficial, wise, and favorable.

Subjective Norm Behavior

This construct included four items associated with the perception of family, people consumers value as relevant (e.g., teachers), close friends and other consumers of this kind of product.

Perceived Behavioral Control

This scale was measured with three items and used Likert ratings between 1 and 7 to evaluate them: “It is totally up to me whether I will eat healthily or not,” “For me eating healthily is…” and “I am very confident that I will eat healthily.”

Moderation Variable

Need for Relatedness

This was the moderator construct in our theoretical model. The items were measured with the following structure: 1 = not at all true; 2 = somewhat true; 3 = fairly true; 4 = completely true. The original scale had three items: I get along well with people I come into contact with; I consider myself close to the people I regularly interact with; and people in my life care about me.

Model

A SEM multigroup model was created to evaluate the relationships of the theoretical model. When there is a moderation variable in the SEM, it is necessary to include the combination of items of the independent variable with items of the moderation variable. In this case, the new variable is calculated by combining the items of the need for relatedness and self-reported eating. This study used the common variance method to detect variance problems between the independent variables. This test is useful when the data were collected with an information-gathering instrument. Harman’s one-factor test concluded that there were no problems of common method variance in the data collection.

To analyze the psychometric properties of the scales, a correlational analysis and exploratory factor analysis were used for each scale to identify its fit and one-dimensionality. Subsequently, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to assess the convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs (SCR (Scale Composite Reliability) was higher than 0.7 and AVE (Average Variance Extracted) was higher than 0.6 in the constructs) (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Additionally, the t value had high values, generating evidence of convergent validity (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1988). When the AVE test in each scale had high values compared to latent variables with shared variance, discriminant validity was validated (Escandon-Barbosa et al., Citation2019). Discriminant validity examined that our constructs, in theory, were not connected with each other. Different indicators, such as the GFI (Goodness of Fit Indicator), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation), SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), and TLI (Tucker Lewis index), are used to examine the model’s adjustment. For the GFI, CFI, and TLI indicators, a minimum value of 0.80 is required to prove the model’s quality. For the RMSEA, a value between 0.05 and 0.08 is required, and the SRMR must be less than 0.08 to demonstrate that errors do not present a risk to the model’s adjustment. The resulting fit statistics are χ2 (980) = 271.75; GFI = 0.43; RMSEA = 0.071; SRMR = 0.06; CFI = 0.93; and TLI (NNFI) = 0.93. These fit statistics confirmed that our model has a good level of adjusted and it will useful to evaluate the hypothesis. presents the descriptive statistics, correlation coefficients, compound reliability and average variance extracted for each measurement scale (see ).

Table 1. Mean, SD, SCR and AVE.

Results

The results indicate that the model has goodness of fit and adjustment. The SEM is satisfactory (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988). The resulting statistical adjustments for the total sample are χ2 = 390.15; RMSEA = 0.062; CFI = 0.94; and TLI = 0.93. The multigroup results are χ2 = 370.15; RMSEA = 0.059; CFI = 0.966; and TLI = 0.956.

presents the analysis of the results of the theoretical model for each of the hypotheses proposed. Hypothesis 1 (H1) is accepted for both Colombia and Spain. It is confirmed that attitude toward the behavior positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior (H1a: β1Colombia = 0.814; p < .01) and (H1b: β1Spain = 0.705; p < .01). With respect to Hypothesis 2 (H2), it is established that subjective norm behavior positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior. The hypothesis is supported for both Colombia and Spain (H2a: γ21Colombia = 0.231; p < .01; H2b γ21Spain = 0.206; p < .01). However, it is not possible to confirm whether perceived behavioral control positively influences self-reported healthy eating behavior (H3a: γ21Colombia = 0.021; p > .1 H3b: γ21Spain = 0.081; p > .1;). Thus, Hypothesis 3 (H3) is rejected.

Table 2. Model.

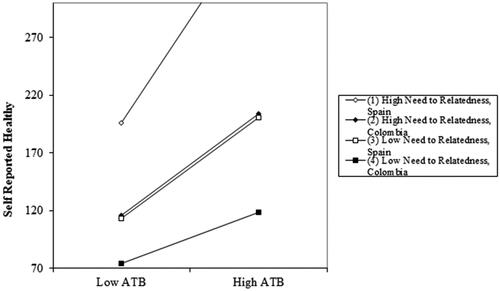

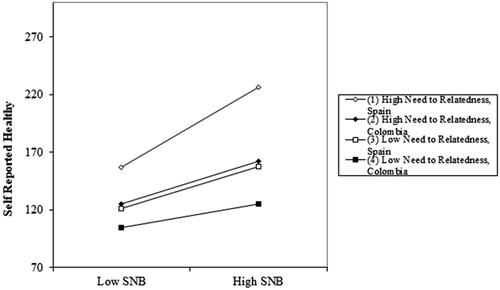

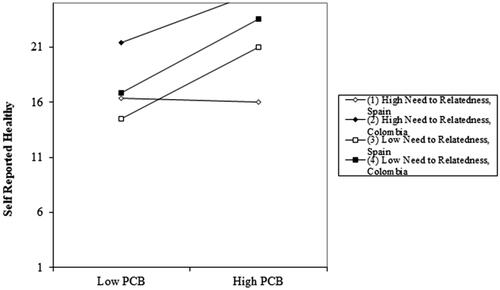

Based on the results obtained and presented, display the moderation effects of the need for relatedness on three relationships: (1) attitude toward the behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior; (2) subjective norm behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior; and (3) perceived behavioral control and self-reported healthy eating behavior.

Figure 2. Moderating effects of the need for relatedness on the relationship between attitude toward the behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior.

Figure 3. Moderating effects of the need for relatedness on the relationship between social norm behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior.

Figure 4. Moderating effects of the need for relatedness on the relationship between perceived behavioral control and self-reported healthy eating behavior.

According to Dawson and Richter (Citation2006) and Escandon-Barbosa and Hurtado-Ayala (Citation2020), a graphical representation is a requirement for analyzing moderation effects because the pathway allows the inflection to be checked or the trajectory to be changed when the moderation variable is included. Aiken and West (Citation1992) affirm that the variables need to be centered on the mean, and for each relationship, low and high levels should be calculated. A low level is obtained with one negative standard deviation of the moderation variable. For high values, one positive standard deviation is used. According to Aiken and West (Citation1992), the procedure involves analyzing whether self-reported healthy eating behavior varies with changes in each independent variable through changes in the need for relatedness.

shows the moderation of the need for relatedness on the relationship between attitude toward the behavior (ATB) and self-reported healthy eating behavior. In general, when the need for relatedness () increases, the positive effect of attitude toward the behavior on self-reported healthy eating behavior increases. Therefore, Hypothesis 4 (H4) is accepted for Spain; that is, the need for relatedness moderates the relation between attitude toward the behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior (γ41 = 0.72; t = 11.05; p < .01). Colombia shows less relevance of the need for relatedness, but it is significant (γ42 = 0.612; t = 1.42; p < .001).

shows the moderation of the need for relatedness on the relationship between subjective norm behavior (SNB) and self-reported healthy eating behavior, similar to that found in the previous relationship. When the need for relatedness () increases, the positive effect of ATB on self-reported healthy eating behavior increases. Hypothesis 5 (H5), which states that the need for relatedness moderates the relation between subjective norm behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior, is confirmed in Spain (H5b: γ51 = 0.854; p < .01) and rejected in Colombia (H5a: γ52 = 0.12; t = 1.03; p > .1).

These results related to moderating effects coincide with the evidence obtained by authors such as Ryan and Deci (Citation2002), who affirm that the need for relatedness may generate a sense of response to social norm behavior and therefore increase self-reported healthy eating behavior.

Finally, shows the moderating effects of the need for relatedness on the relationship between perceived control of behavior and self-reported healthy eating behavior. In this case, the moderation effect on the relationship between PCB and self-reported healthy eating behavior is not significant because this behavior does not increase the relevance of the relationship, and similar results are obtained without the need for relatedness. Therefore, perceived control of behavior and its consequences for self-reported healthy eating behavior did not change during the pandemic when the need for relatedness increased in the millennial population. Therefore, the moderation effect of the need for relatedness on perceived behavioral control and self-reported healthy eating behavior is confirmed in Spain (H6b (Hypothesis 6): γ61 = 0.93; p > .1) and rejected in Colombia (H6a: γ62 = 0.08; t = 0.88; p > .1).

Conclusions

This research focuses on the need for relatedness in the relationship between behavioral intention and healthy food consumption in pandemic conditions. The results allow us to observe the influence of the need for relatedness on the intention to carry out a particular behavior. To achieve this objective, a structural equation model is used for a sample of 1190 young people aged 25 to 34 years old in Colombia and Spain. The results show how behavioral intentions affect the adoption of healthy food consumption and how variables such as the need to interact moderate this relationship.

Investigating the effects of the pandemic on behavior is necessary not only from the perspective of public health but also from consumer behavior and psychology. The present research contributes to identifying variables such as the need for relatedness and their relationship in adopting behavioral dynamics. Another aspect that is currently relevant is related to how population segments such as Colombians and Spaniards assume consumer behaviors and adopt habits. Healthy consumption habits continue to be one of the main concerns of countries worldwide, given the effect on the generation of diseases in segments of the young population.

The need for relatedness is associated with social isolation conditions generated by COVID-19, in which individuals develop behaviors related to their attitude and their levels of social interaction. Individuals have intentions that enable the adoption of behaviors when they positively evaluate an attitude. The same happens with social interactions; social pressure induces a positive evaluation of behavior. Similarly, the results show that social interaction assumes a fundamental role in individual well-being and the adoption of behaviors. The previous allows us to see more clearly how segments of the population, such as millennials, respond to external factors and the internalization of consumption habits. According to the theory of planned behavior, the effects of attitudes have a strong influence on the adoption of a habit. However, social norms and perceived behavior control could not be verified for either country.

There may be a greater need to interact with others in European countries. Therefore, the pandemic restrictions directly influence the consumption patterns already defined. Given that the nature of North America is more individualistic, there was no significant moderating effect in this type of relationship despite pandemic conditions.

Regarding attitude toward the behavior, it has a positive influence in countries such as Colombia and Spain. This is because social conditions determine the evaluation of certain behaviors. Scholars such as Elmadfa and Meyer (Citation2015) state that in countries such as Colombia and Spain, this type of evaluation is strong and gives greater importance to healthy habits. It is essential to highlight that it is precisely the attitude toward the behavior that allows establishing evaluations in adopting eating behaviors. In this way, it is clearly determined how a psychological component of the individual interacts with the environmental conditions that predict individual behavior through social reward or punishment.

The subjective norms that were verified for Spain suggest a greater inclination to share moments socially than for countries such as Colombia. On the other hand, PBC is associated with the degree of control that influences the adoption of a behavior. For Colombia, the results show no significance in principle because its social and regulatory conditions are not as strong as those of European countries, where rules and regulations are strictly enforced by the country’s institutions. On the other hand, the subjective norms allow identifying the social pressures that lead to adopting healthy behavior. This is how the influence of social groups and the factors that determine the environment is established as keys to promulgate the adoption of certain habits in specific populations.

Perceived behavioral control could not be validated for Colombia since defined food consumption habits make controlling this behavior difficult; therefore, self-reported healthy eating behavior is not likely to be adopted (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2011). An important aspect to highlight is that even if an individual perceives being able to control behavior, this perception is not sufficient to adopt the behavior. Therefore, there are additional aspects that outweigh the perceived control capacity. One of these is the psychological aspect associated with social norms, which enables analyzing internalizing ideas and behaviors stimulated by external factors such as social interaction (Ryan, Citation1995; Ryan & Deci, Citation2002). It is necessary to mention that the perceived control conditions the resources and opportunities of the environment that leads to the adoption of a behavior. Thus, the individual begins to evaluate the degree of importance of the resources he possesses and the conditions for developing an eating habit. This condition would have severe implications in developing conditions for healthy life habits in specific populations.

Conditions such as the pandemic have generated great changes in the behaviors adopted by individuals. These behaviors can be assumed to be permanent given the implications at the public health level, such as those generated by COVID-19. Thus, knowing the implications and main factors that affect behavior is important at the public health level and in the services market.

Satisfaction with the need for relatedness is positively associated with well-being in adopting a behavior (Reis et al., Citation2000; Sheldon & Niemiec, Citation2006). The need for relatedness during a pandemic is evaluated as an aspect of significant importance by millennials in adopting healthy consumption habits. In isolated conditions, people begin to value the need for self-care and self-reported healthy eating behavior.

Management Implications

One of the implications is the ability to develop public policies that allow for the creation of public health conditions, generating healthy behaviors based on consumer behavior analysis. Decision-makers are usually interested in health coverage indicators. However, elements such as habits and behaviors are left aside. This way, conceptualizing eating patterns becomes an intervention mechanism for specific population segments, especially young people. Studies in the field have shown that the intervention processes have reduced dissatisfaction with the perception of the body’s state of health. At the same time, the intervention could help with eating disorders in segments of the young population. Focusing on nutrition where young population segments are characterized by eating disorders, and low-quality diets becomes essential for health prevention and improving nutritional profiles.

Limitations

The present research has limitations that need to be considered. These limitations are related to the sample, which involved a population in a developing country. Countries such as Colombia and Spain have very particular characteristics that may differ from the dynamics of developed countries. Another limitation is the use of cross-sectional data, which does not allow for the analysis of long-term behavioral changes and the impact of moderating effects.

Future Research Avenues

The results suggest the need to continue to examine additional variables that influence the adoption of healthy consumption habits. One relevant aspect in the study of behavior is the influence of social networks on adopting consumption patterns, given the current importance in pandemic conditions. Another important aspect is conducting comparative studies between millennials and other population segments that allow differences to be identified between the behaviors adopted by each generation. Finally, it is essential to analyze other variables considered in studies of other scholars’ theories of planned behavior. These variables could be essential to consider in the study of conditioned behaviors.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmad, M., Iram, K., & Jabeen, G. (2020). Perception-based influence factors of intention to adopt COVID-19 epidemic prevention in China. Environmental Research, 190, 109995. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109995

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. C. (1992). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Choice Reviews Online, 29(06), 29–3352. doi:10.5860/choice.29-3352

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Al-Jubari, I., Hassan, A., & Liñán, F. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention among university students in Malaysia: Integrating self-determination theory and the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(4), 1323–1342. doi:10.1007/s11365-018-0529-0

- Alkhathami, A. A., Duraihim, A. T., Almansour, F. F., Alotay, G. A., Alnowaiser, H. S., Aboul-Enein, B. H., … Benajiba, N. (2021). Assessing use of caloric information on restaurant menus and resulting meal selection in Saudi Arabia: Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. American Journal of Health Education, 52(3), 154–163. doi:10.1080/19325037.2021.1902885

- Al-Rafee, S., & Cronan, T. P. (2006). Digital piracy: Factors that influence attitude toward behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(3), 237–259. doi:10.1007/s10551-005-1902-9

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Ateş, H., Demir Özdenk, G., & Çalışkan, C. (2021). Determinants of science teachers’ healthy eating behaviors: Combining health belief model and theory of planned behavior. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 20(4), 573–589. doi:10.33225/jbse/21.20.573

- Bagozzi, R., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94. doi:10.1007/BF02723327

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Bebetsos, E., Chroni, S., & Theodorakis, Y. (2002). Physically active students’ intentions and self-efficacy towards healthy eating. Psychological Reports, 91(2), 485–495. doi:10.2466/pr0.2002.91.2.485

- Bebetsos, E., Theodorakis, I., Laparidis, K., & Chroni, S. (2000). Reliability and validity of a self-confidence scale for a healthy eating questionnaire. Health and Sport Performance, 3, 191–203.

- Burton, R. J. (2004). Reconceptualising the ‘behavioural approach’ in agricultural studies: A socio-psychological perspective. Journal of Rural Studies, 20(3), 359–371. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2003.12.001

- Callea, A., De Rosa, D., Ferri, G., Lipari, F., & Costanzi, M. (2019). Are more intelligent people happier? Emotional intelligence as mediator between need for relatedness, happiness, and flourishing. Sustainability, 11(4), 1022. doi:10.3390/su11041022

- Carlton, C. N., Garcia, K. M., Andino, M. V., Ollendick, T. H., & Richey, J. A. (2022). Social anxiety disorder is Associated with Vaccination attitude, stress, and coping responses during COVID-19. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 2022, 1–11.

- Cartagena, J. J. R. (2017). Millennials y redes sociales: estrategias para una comunicación de marca efectiva. Miguel Hernández communication journal, 8, 347–367. doi:10.21134/mhcj.v0i8.196

- Chaba, L., Scoffier-Mériaux, S., d’Arripe-Longueville, F., & Lentillon-Kaestner, V. (2021). Eating behaviors among male bodybuilders and runners: Application of the trans-contextual model of motivation. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 15(4), 373–394. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2019-0097

- Chen, C., Gong, X., Wang, J., & Gao, S. (2021). Does need for relatedness matter more? The dynamic mechanism between teacher support and need satisfaction in explaining Chinese school children’s regulatory styles. Learning and Individual Differences, 92, 102083. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102083

- Chen, S. C., & Hung, C. W. (2016). Elucidating the factors influencing the acceptance of green products: An extension of theory of planned behavior. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 112, 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.022

- Chen, Y., Lee, B. F., & Lu, Y. C. (2021). Fitnesser’s Intrinsic Motivations of Green Eating: An Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Hedonic-Motivation System Adoption Model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670243

- Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 917–926.

- de Araujo, P. F. (2021). The Applicability of Self-Determination Theory for Cross-cultural Coaching: A Study with Assigned and Self-initiated Expatriates. International journal of evidence based coaching and mentoring, Special Issue 15, 96–109. doi:10.24384/4xd8-5t97

- Kervenoael, R., Schwob, A., Hasan, R., & Ting, Y. S. (2021). Consumers’ perceived value of healthier eating: A SEM analysis of the internalisation of dietary norms considering perceived usefulness, subjective norms, and intrinsic motivations in Singapore. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(3), 550–563. doi:10.1002/cb.1884

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. [Database] doi:10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Self-determination research: Reflections and future directions. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 431–441). University of Rochester Press.

- Deng, Q., Zheng, Y., Lu, J., Zeng, Z., & Liu, W. (2021). What factors predict physicians’ utilization behavior of contrast-enhanced ultrasound? Evidence from the integration of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Technology Acceptance Model using a structural equation modeling approach. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 21(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12911-021-01540-8

- Douglas, M. E., Blumenthal, H., & Guarnaccia, C. A. (2021). Theory of planned behavior and college student 24-hour dietary recalls. Journal of American College Health, 2021, 1–8.

- Elmadfa, I., & Meyer, A. L. (2015). Patterns of drinking and eating across the European Union: Implications for hydration status. Nutrition Reviews, 73(suppl 2), 141–147. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv034

- Escandon-Barbosa, D., & Hurtado-Ayala, A. (2020). Effects of market orientation and learning orientation on organisational performance. Global Business and Economics Review, 22(3), 249–269. doi:10.1504/GBER.2020.106246

- Escandon-Barbosa, D., Hurtado-Ayala, A., Rialp-Criado, J., & Salas-Paramo, J. A. (2020). Identification of consumption patterns: an empirical study in millennials. Young Consumers, 22(1), 90–111. doi:10.1108/yc-11-2018-0872

- Escandon-Barbosa, D., Urbano-Pulido, D., & Hurtado-Ayala, A. (2019). Exploring the relationship between formal and informal institutions, social capital, and entrepreneurial activity in developing and developed countries. Sustainability, 11(2), 550. doi:10.3390/su11020550

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2011). Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach (1st ed.). Psychology Press. doi:10.4324/9780203838020

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312

- Freund, P. A., & Lohbeck, A. (2020). Modeling self-determination theory motivation data by using unfolding IRT. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 37(5), 388-396. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000629

- Harter, S. (1978). Effectance motivation reconsidered. Toward a developmental model. Human Development, 21(1), 34–64. doi:10.1159/000271574

- Hasheminezhad, A., & Yazdan-Panah, M. (2016). Determine factors that influenced students’ intention regarding consumption of organic product: Comparison theory of planned behaviour and health belief model. Iranian Journal of Agricultural Economics and Development Research, 46(4), 817–831.

- Horney, K. (1945). Our Inner Conflicts. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc.

- Hsu, C. L., Chang, C. Y., & Yansritakul, C. (2017). Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 145–152. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.006

- Huang, Y., Aguilar, F., Yang, J., Qin, Y., & Wen, Y. (2021). Predicting citizens’ participatory behavior in urban green space governance: Application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 61, 127110. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127110

- Imani, B., Allahyari, M. S., Bondori, A., Surujlal, J., & Sawicka, B. (2021). Determinants of organic food purchases intention: The application of an extended theory of planned behaviour. Futhure and Food, 10(6), 10.

- Irfan, M., Akhtar, N., Ahmad, M., Shahzad, F., Elavarasan, R. M., Wu, H., & Yang, C. (2021). Assessing public willingness to wear face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic: Fresh insights from the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4577. doi:10.3390/ijerph18094577

- Johnston, M. M., & Finney, S. J. (2010). Measuring basic needs satisfaction: Evaluating previous research and conducting new psychometric evaluations of the Basic Needs Satisfaction in General Scale. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 35(4), 280–296. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2010.04.003

- Jones, D., Feigenbaum, P., & Jones, D. F. (2021). Motivation (constructs) made simpler: Adapting self-determination theory for community-based youth development programs. Journal of Youth Development, 16(1), 7–28. doi:10.5195/jyd.2021.1001

- Khani Jeihooni, A., Jormand, H., Saadat, N., Hatami, M., Abdul Manaf, R., & Afzali Harsini, P. (2021). The application of the theory of planned behavior to nutritional behaviors related to cardiovascular disease among the women. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 21(1), 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12872-021-02399-3

- Kushwah, S., Dhir, A., Sagar, M., & Gupta, B. (2019). Determinants of organic food consumption. A Systematic Literature Review on Motives and Barriers. Appetite, 143, 104402. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2019.104402

- Kymäläinen, T., Seisto, A., & Malila, R. (2021). Generation Z food waste, diet, and consumption habits: A Finnish social design study with future consumers. Sustainability, 13(4), 2124. doi:10.3390/su13042124

- La Barbera, F., & Ajzen, I. (2020). Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: Rethinking the role of subjective norm. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 16(3), 401–417. doi:10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2056

- LaCaille, R. A., Hooker, S. A., & LaCaille, L. J. (2020). Using self-determination theory to understand eating behaviors and weight change in emerging adults. Eating Behaviors, 39, 101433. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2020.101433

- Lai, I. J., Chang, L. C., Lee, C. K., & Liao, L. L. (2021). Nutrition literacy mediates the relationships between multi-level factors and college students’ healthy eating behavior: Evidence from a Cross-sectional study. Nutrients, 13(10), 3451. doi:10.3390/nu13103451

- Lehberger, M., Kleih, A. K., & Sparke, K. (2021). Panic buying in times of coronavirus (COVID-19): Extending the theory of planned behavior to understand the stockpiling of nonperishable food in Germany. Appetite, 161, 105118. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2021.105118

- Linos, K., Jakli, L., & Carlson, M. (2021). Fundraising for stigmatized groups: A text message donation experiment. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 14–30. doi:10.1017/S0003055420000787

- Liobikienė, G., Dagiliūtė, R., & Juknys, R. (2021). The determinants of renewable energy usage intentions using theory of planned behaviour approach. Renewable Energy. 170, 587–594. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.01.152

- Lucarelli, C., Mazzoli, C., & Severini, S. (2020). Applying the theory of planned behavior to examine pro-environmental behavior: The moderating effect of COVID-19 beliefs. Sustainability, 12(24), 10556. doi:10.3390/su122410556

- Maas, J., Schoch, S., Scholz, U., Rackow, P., Schüler, J., Wegner, M., & Keller, R. (2022, March). Satisfying the need for relatedness among teachers: Benefits of searching for social support. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 7, p. 851819). Lausanne: Frontiers Media SA.

- Mahdavi, T. (2021). Application of the ‘theory of planned behavior’ to understand farmers’ intentions to accept water policy options using structural equation modeling. Water Supply, 21(6), 2720-2734. doi:10.2166/ws.2021.138

- Massey, M., O’Cass, A., & Otahal, P. (2018). A meta-analytic study of the factors driving the purchase of organic food. Appetite, 125, 418–427. doi:10.1016/j.Appet.2018.02.029

- Miconi, D., Li, Z., Frounfelker, R. L., Santavicca, T., Cénat, J. M., Venkatesh, V., & Rousseau, C. (2020). Ethno-cultural disparities in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study on the impact of exposure to the virus and COVID-19-related discrimination and stigma on mental health across ethno-cultural groups in Quebec (Canada). British Journal of Psychiatry Open, 7(1), 146. doi:10.1192/bjo.2020.146

- Mišovič, J. (2022). Konformita, společenský fenomén projevující se v chování většiny lidí. Historická Sociologie, 14(1), 91–107. doi:10.14712/23363525.2022.6

- Moore, E., Holding, A. C., Moore, A., Levine, S. L., Powers, T. A., Zuroff, D. C., & Koestner, R. (2021). The role of goal-related autonomy: A self-determination theory analysis of perfectionism, poor goal progress, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 68(1), 88–97. doi:10.1037/cou0000438

- Moraes, C. H. D. C., Alvarenga, M. D. S., Moraes, J. M. M., & Cyrillo, D. C. (2021). Exploring psychosocial determinants of eating behaviour: Fruits and vegetables intake among Brazilian adolescents. Frontiers in Nutrition, 2021, 1071.

- Morrison, O. (2019). Younger consumers more likely to pay higher prices for organic food and drink: Mintel by foodnavigator. Extracted June 28, 2021. Retrieved October 4, 2019, from https://www.Foodnavigator.Com/article/2019/10/04/younger-consumers-more-likely-to-pay-higher-prices-for-organic-food-and-drink-mintel.

- Nguyen-Rodriguez, S. T., Chou, C. P., Unger, J. B., & Spruijt-Metz, D. (2008). BMI as a moderator of perceived stress and emotional eating in adolescents. Eating Behaviors, 9(2), 238–246. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.09.001

- Oliver, G., & Wardle, J. (1999). Perceived effects of stress on food choice. Physiology & Behavior, 66(3), 511–515. doi:10.1016/S0031-9384(98)00322-9

- Pang, S. M., Tan, B. C., & Lau, T. C. (2021). Antecedents of Consumers’ Purchase Intention towards Organic Food: Integration of Theory of Planned Behavior and Protection Motivation Theory. Sustainability, 13(9), 5218. doi:10.3390/su13095218

- Paul, J., Modi, A., & Patel, J. (2016). Predicting green product consumption using theory of planned behavior and reasoned action. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 29, 123–134. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.11.006

- Peetz, J., & Milyavskaya, M. (2021). A self-determination theory approach to predicting daily prosocial behavior. Motivation and Emotion, 45(5), 617–630. doi:10.1007/s11031-021-09902-5

- Pérez-Cueto, F. J., Aschemann-Witzel, J., Shankar, B., Brambila-Macias, J., Bech-Larsen, T., Mazzocchi, M., … Verbeke, W. (2012). Assessment of evaluations made to healthy eating policies in Europe: A review within the EATWELL Project. Public Health Nutrition, 15(8), 1489–1496. doi:10.1017/S1368980011003107

- Pinsker, H. (2001). Introducción a la psicoterapia de apoyo. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.

- Pitchay, A. A., Eliz, N. M. A., Ganesan, Y., Mydin, A. A., Ratnasari, R. T., & Thaker, M. A. M. T. (2021). Self-determination theory and individuals’ intention to participate in donation crowdfunding. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 15(3), 506–526. doi:10.1108/imefm-08-2020-0424

- Psouni, S., Hassandra, M., & Theodorakis, Y. (2016). Exercise and healthy eating intentions and behaviors among normal weight and overweight/obese adults. Psychology, 07(04), 598–611. doi:10.4236/psych.2016.74062

- Rana, J., & Paul, J. (2017). Consumer behavior and purchase intention for organic food: A review and research agenda. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 38, 157–165. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.06.004

- Rana, J., & Paul, J. (2020). Health motive and the purchase of organic food: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 44(2), 162–171. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12556

- Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(4), 419–435. doi:10.1177/0146167200266002

- Rueda Barrios, G. E., Rodriguez, J. F. R., Plaza, A. V., Vélez Zapata, C. P., & Zuluaga, M. E. G. (2021). Entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Colombia: Exploration based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Education for Business, 2021, 1–10.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. Handbook of self-determination research, 2, 3–33.

- Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63(3), 397–427. 1995

- Sun, S. Y., Qin, B., Hu, Z., Li, H., Li, X., He, Y., & Huang, H. (2021). Predicting mask-wearing behavior intention among international students during COVID-19 based on the theory of planned behavior. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(4), 3633–3647.

- Santana, F. N., Fischer, S. L., Jaeger, M. O., & Wong-Parodi, G. (2020). Responding to simultaneous crises: Communications and social norms of mask behavior during wildfires and COVID-19. Environmental Research Letters, 15(11), 111002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abba55

- Scalco, A., Noventa, S., Sartori, R., & Ceschi, A. (2017). Predicting organic food consumption: A meta-analytic structural equation model based on the theory of planned behavior. Appetite, 112, 235–248. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2017.02.007

- Schachter, S. (1971). Emotion, obesity, and crime. New York: Academic Press, Inc.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Niemiec, C. P. (2006). It’s not just the amount that counts: Balanced need satisfaction also affects well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(2), 331–341. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.2.331

- Shmueli, L. (2021). Predicting intention to receive COVID-19 vaccine among the general population using the health belief model and the theory of planned behavior model. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-10816-7

- Shubayr, M. A., Mashyakhy, M., Al Agili, D. E., Albar, N., & Quadri, M. F. (2020). Factors associated with infection-control behavior of dental health – Care workers during the Covid-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study applying the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 13, 1527–1535. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S278078

- Sims, R., Gordon, S., Garcia, W., Clark, E., Monye, D., Callender, C., & Campbell, A. (2008). Perceived stress and eating behaviors in a community-based sample of African Americans. Eating Behaviors, 9(2), 137–142. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.06.006

- Tao, Y., Duan, M., & Deng, Z. (2021). Using an extended theory of planned behaviour to explain willingness towards voluntary carbon offsetting among Chinese consumers. Ecological Economics, 185, 107068. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107068

- The Food Standards Agency. (2019). Future Consumer: Food and Generation Z. Retrieved from https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/generation-z-full-report-final.pdf.

- Trifiletti, E., Shamloo, S. E., Faccini, M., & Zaka, A. (2021). Psychological predictors of protective behaviours during the Covid‐19 pandemic: Theory of planned behaviour and risk perception. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 32(3), 382-397. doi:10.1002/casp.2509

- Tsang, H. W., Chua, G. T., To, K. K. W., Wong, J. S. C., Tu, W., Kwok, J. S. Y., … Ip, P. (2021). Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 immunity in convalescent children and adolescents. Frontiers in Immunology, 12, 97919. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.797919.

- Verain, M. C., Bouwman, E. P., Galama, J., & Reinders, M. J. (2022). Healthy eating strategies: Individually different or context-dependent? Appetite, 168, 105759. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2021.105759

- Vinnell, L. J., Milfont, T. L., & McClure, J. (2019). Do social norms affect support for earthquake-strengthening legislation? Comparing the effects of descriptive and injunctive norms. Environment and Behavior, 51(4), 376–400. doi:10.1177/0013916517752435

- Wang, M., Jin, Z., Fan, S., Ju, X., & Xiao, X. (2021). Chinese residents’ preferences and consuming intentions for hotels after COVID-19 pandemic: A theory of planned behaviour approach. Anatolia, 32(1), 132–135. doi:10.1080/13032917.2020.1795894

- White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66(5), 297–333. doi:10.1037/h0040934

- Xia, Y., Shi, L.-S.-B., Chang, J.-H., Miao, H.-Z., & Wang, D. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on intention to use traditional Chinese medicine: A cross-sectional study based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 19(3), 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.joim.2021.01.013

- Xiang, S., Zhang, Y., Ning, N., Wu, S., & Chen, W. (2021). How does leader empowering behavior promote employee knowledge sharing? The perspective of self-determination theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 2021, 3693.

- Yazdan-Panah, M., Komendantova, N., Shirazi, Z. N., & Linnerooth-Bayer, J. (2015). Green or in between? Examining youth perceptions of renewable energy in Iran. Energy Research & Social Science, 8, 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2015.04.011

- Yildiz, V. A., & Kiliç, D. (2021). Motivation and motivational factors of primary school teachers from the Self-Determination Theory perspective. Turkish Journal of Education, 10(2), 76–96.

- Yushi, J., Naqvi, M. H. A., & Naqvi, M. H. (2018). Using social influence processes and psychological factors to measure pervasive adoption of social networking sites: Evidence from Pakistan. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 54(15), 3485–3499. doi:10.1080/1540496X.2017.1417834

- Zhao, F., Roehrig, G., Patrick, L., Levesque-Bristol, C., & Cotner, S. (2021). Using a self-determination theory approach to understand student perceptions of inquiry-based learning. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 9(2), n2. doi:10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.2.5