Abstract

Research has demonstrated how LGBTQ+ hate is widespread on the internet. The nature of the online world is such that the permanence and desistance of hate is greater than its offline counterpart. However, comparatively little attention has been paid to the impacts of this type of behavior. Drawing on the findings of a survey involving 175 LGBTQ+ respondents aged 13–25, and 15 follow-up interviews, this paper addresses this gap by exploring the range of significant impacts that LGBTQ+ young people experience on their well-being and relationships with others. Given the ubiquitous nature of online abuse, this paper demonstrates the need for a targeted criminal justice response. Consequently, this paper discusses the implications of the findings with respect to future research.

INTRODUCTION

The rise of the internet as an online community space represents a symbol of technological ingenuity and a new era of social interactions (Wall, Citation2001). In particular, LGBTQ+ youth establish online safe spaces to explore their gender and sexuality, whilst building authentic peer connections (De Ridder & Van Bauwel, Citation2015). However, there is a darker side of internet use, with LGBTQ+ young people becoming increasingly vulnerable to online hate (Marston, Citation2019).

Online hate as a concept is not new, however we are seeing increasing levels of awareness within policy and scholarship domains. Prior to this, hate crime discussions have precluded any meaningful understanding of microaggressions and “every day” hate, by largely focusing on acts of violence and discrimination that are deemed liable for criminal justice responses (Chakraborti, Citation2018). However, online hate speech, including incidents that do not meet the threshold of “crime,” are now being considered as a problem in their own right. Described as an “endemic” (Bachmann & Gooch, Citation2017: p4) research demonstrates that LGBTQ+ people are more vulnerable to online hate than their heterosexual, cisgender peers (Powell et al., Citation2020; Marston, Citation2019). Yet current criminal justice models fail to appropriately engage with the nature and harms of this novel form of online hate.

Previous research into LGBTQ+ online hate has not considered the full spectrum of targeted abuse, and therefore our attempts to understand this pernicious social problem are lacking context (Williams, Citation2019). Moreover, where current literature demonstrates the varied impacts of offline hate, comparatively little attention has been paid to the impacts of online hate on LGBTQ+ youth. As such, research has overlooked how the permanence and desistance of online hate amplifies both the direct and bystander effects experienced by LGBTQ+ youth (Williams, Citation2019). Our understanding of the extreme impacts of offline hate, including increased rates of depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide (Cooper & Blumenfeld, Citation2012; McDermott, Citation2015; Williams, Citation2019) demonstrate the importance of understanding the impacts of online hate on LGBTQ+ youth.

This paper seeks to address the gap in current understandings of LGBTQ+ online hate. Drawing on findings from a survey involving 175 LGBTQ+ respondents aged 13-25, and 15 follow-up semi-structured interviews, this paper details a range of significant impacts that LGBTQ+ young people experience, showcasing how online hate is damaging and a cause for concern (Keighley, Citation2022). Consequently, this paper demonstrates the importance of a harms focused approach to criminal justice. In order to judiciously present this argument, the first section of this paper provides a summary of key literature, including problems defining LGBTQ+ online hate within the legal sphere, and attempts to quantify incidence rates of LGBTQ+ targeted hate. Second, the methodology is reported, including details of the sample and participant recruitment process. Finally, this paper presents some key findings with respect to the impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate on young people. By developing our understanding of the ubiquitous nature of this novel form of hate, this paper suggests a need for prioritizing meaningful responses to support LGBTQ+ young people within and beyond criminal justice avenues. Most notably, this paper demonstrates a need to transform criminal justice policy to be inclusive of the harms of online hate. Such a reformation of criminal justice frameworks together with a coalition of multilateral efforts will be most effective in reducing the harm caused by hate online (Banks, Citation2010).

LGBTQ+ ONLINE HATE

Defining LGBTQ+ Online Hate

Online hate is neither clearly, nor consistently defined in legal and academic research circles and there are important distinctions made between hate crime and hate speech. Within the matrix of defining what constitutes online hate, criminal justice institutions are interested in the criminal aspects only. The Council of Europe, alongside the Committee of Ministers, is the first and only international intergovernmental organization to have adopted an official definition of hate speech. Recommendation (97)20 defines hate speech as, “covering all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance” (Council of Europe, Citation1997, p. 107). This was refined in 2008 by the European Union following a consultation to include,

all conduct publicly inciting to violence or hatred directed against a group of persons or a member of such a group defined by reference to race, colour, religion, descent or national or ethnic origin (Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA)

Whilst certainly a clearer definition in scope, by solely focusing on public incitements to violence of hatred, private incidents are excluded. Moreover, it remains unclear whether sexuality and/or gender identity are protected characteristics as no mention is given anywhere in the legal summary.

However well-intentioned these legal definitions may be, difficulties arise when deciding at what point speech crosses the line from an expression of opinion to an illegal act (CPS (Crown Prosecution Service),), Citation2019). In most countries, the law makes a distinction between a hate crime (liable for criminal sanction), a hate incident (non-criminal offence) and hate speech (which may or may not constitute a criminal offence). To use the UK as an example, as a country who meticulously records hate crime incidents at a higher rate than comparable countries (FRA, Citation2018), the police are obliged to record all hate crimes and hate incidents (UK Council for Internet Safety (UKCIS), Citation2019). Hate speech, which commonly occurs online, is often left out of hate crime and hate incident reports. Thus, a problem arises when policing online hate from a merely legal standpoint. Failing to include online hate speech in a legal definition, is to underestimate the tangible harms and negative outcomes on LGBTQ+ people experiencing online hate. Currently, our legal understanding of hate online sits apart from contextual facts, such as the causes and consequences of these acts (Siegel, Citation2020). This is despite the extensive literature detailing the harms of wider identity targeted hate online (Sellars, Citation2016). This is none more pronounced than when offensive and controversial hate speech falls under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights (Council of Europe, Citation2020). Article 10 allows for certain protections for freedom of speech that includes the freedom to offend others. Furthermore, the geographic indeterminacy of the internet has meant that States with diverging hate and free speech laws have clashed over jurisdictional rights when attempting to prosecute hate cases (Banks, Citation2010). There are inherent difficulties in both policing online hate according to geographical demarcations, but also by seeking to extend jurisdictional powers when enforcing content and regulation laws in States that do not concur. Thus, our understandings of online hate are clouded by a judgment on criminal culpability and freedom of speech.

Online hate beyond what is considered a crime is the object of intense scrutiny by academic scholarship. There are again problems with consistency in terms, which is likely affecting understandings of LGBTQ+ online hate. “Hate,” “harassment” and “abuse” are often used interchangeably in the academic literature when referring to online hate (Hardy & Chakraborti, Citation2020). Yet these are typically not motivating factors in the commission of an online hate incident and certain acts are not protected under such so-called umbrella concepts (Chakraborti, Citation2018). Thus, despite the important contributions academic definitions have made, a lack of common understanding has garnered a reputation for responding to online hate that is rather permeable (Chakraborti & Hardy, Citation2017; Powell & Henry, Citation2017).

Where both legal and academic definitions of hate speech typically focus on the physical manifestations of the act and the geographical relevancy to State criminal justice agencies, they fail to understand that harm is an important factor to be considered (Banks, Citation2010). A universal definition of hate speech that is inclusive of harms is one which understands that an important facet of the law is to protect its citizens from injury. The European Union’s attempts to harmonize European National Laws marks an important step in effectively responding to hate online within criminal justice spheres (Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA). However, it still fails to engage with hate speech that could be subsumed under freedom of speech protections (Banks, Citation2010). Current criminal justice efforts are limited in their ability to effectively respond to LGBTQ+ online hate. Consequently, online hate is growing exponentially in an online world that is increasingly viewed as lawless.

Prevalence of LGBTQ+ Online Hate

Hate crime, both online and offline, is reportedly on the rise worldwide, with the UK recording a 19% increase in anti-LGB hate crimes from 13,314 incidents per year in 2018/19 to 15,835 per year in 2019/20 and a 16% increase in transgender hate crimes from 2,183 incidents to 2,540 incidents (Home Office, Citation2020). Similar increases have been reported to ODIHR, in which 1272 sexuality and gender-identity motivated bias crimes were recorded across 35 States (ODIHR, Citation2019), an increase from 840 reports across 29 States in 2018 (ODIHR, Citation2018). In the USA, the FBI reported 1393 hate crimes targeting a person’s sexual orientation and/or gender identity (FBI, Citation2019). Whilst hate crime is now firmly under the lens of an international audience, much of this official research fails to include online hate within its scope.

Currently, as a rule, the police do not record online hate crimes to the same extent as their offline equivalents. Therefore, it is important to identify the small, but nonetheless notable body of academic research within the field whose contributions have estimated the high levels of LGBTQ+ online hate. In a recent study by Galop, 96% of UK based LGBTQ+ respondents had experienced more than one incident of online hate in the last five years alone (Hubbard, Citation2020). This is supported by similar figures in the Sussex Hate Crime Project (Paterson et al., Citation2018), in which 83% of 116 LGBTQ+ participants had experienced at least one incident of online hate and 86% had been indirectly victimized online at least once. On a larger scale, Ditch the Label and Brandwatch analyzed 10 million online posts over a three-and-a-half-year period to explore transphobic attitudes in the USA and UK (Brandwatch & Ditch the Label, Citation2019). They found 1.5 million transphobic comments amid wider conversations around trans people and gender identity. In a similar study, Brandwatch and Ditch the Label analyzed 19 million tweets over four years and found 390,296 to include homophobic insults and 19,003 to include transphobic insults (Brandwatch & Ditch the Label, Citation2016).

The aforementioned research has made some noteworthy contributions to our understanding of the insidious nature of LGBTQ+ online hate. Yet the empirical literature fails to account for the role age plays in victimization experiences. This is despite current understandings that young people are among the earliest adopters and most avid users of social media sites (Keipi et al., Citation2016; Ofcom, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). In tangent reports suggest young people are at greater risk of exposure to hate content (Jones et al., Citation2013; Ofcom, Citation2019a, Citation2019b). A small number of studies have found higher rates of online hate targeting LGBTQ+ youth as compared to older demographics. Research by GLSEN and partners in the USA found that one in four (26%) out of 1960 LGBTQ+ youth surveyed, reported being bullied online specifically because of their sexual orientation or gender identity in the past year, and one in five (18%) said they had experienced bullying and harassment via text message (GLSEN et al., Citation2013). In a UK based study, 1 in 20 of 2,544 LGB + people had been the target of homophobic abuse online in the last 12 months. The highest rates of abuse were experienced by the younger cohorts, with 7% being 18 to 24-year-olds (Guasp et al., Citation2013). Similarly, the same study found that 28% of LGB + participants observed online abuse directed at someone else, with the highest proportion being observed by 18 to 24-year-olds (45%). A final study by Myers et al. (Citation2017) collected data from 1,182 young people aged 13–25 from 75 different countries. Their findings suggest bisexual, pansexual and queer participants report higher rates of exposure to cyberbullying than their heterosexual, gay, or lesbian peers.

Taken together, the above empirical research suggests concerning rates of victimization for LGBTQ+ youth and young people globally, with perpetrators and victims of online hate not necessarily residing in the same country (Yar & Steinmetz, Citation2019). However, there is a skepticism toward the concept of online hate, including a general disbelief that it is a problem and an ignorance around the harms associated with it at an individual and community level (Hardy & Chakraborti, Citation2020). Therefore, this article explores the limited research into the effects of LGBTQ+ online hate.

THE IMPACTS OF LGBTQ+ ONLINE HATE

When developing our understanding of LGBTQ+ online hate, we must challenge the assumption that what occurs online is neither harmful, nor inconsequential to a person’s life offline (Hardy & Chakraborti, Citation2020). Williams (Citation2019) argues online hate has the potential to cause greater harms than offline hate due to some unique factors of the internet. The perception or potential for anonymity online means perpetrators of online hate are more likely to offend, and these offenses can be more serious due to the disinhibition effect (Williams, Citation2019). Galop recorded a range of emotional and behavioral responses, similar to those found in the well-documented effects of offline hate (Stray, Citation2017; Williams, Citation2019). Anger, sadness and anxiety were the most highly reported effects (76, 70, and 67% respectively). Respondents also reported a deterioration in mental and physical well-being, including feelings of depression, shame and paranoia.

Moreover, Awan and Zempi (Citation2016) identified blurred boundaries between the online and offline world. Thus, there is a continuity of hate in both the virtual and physical world. It can be difficult to isolate online threats from the possibility of their materializing in the “real world.” Research suggests this leads to withdrawal, social isolation and self-blame for being targeted (Hubbard, Citation2020). Furthermore, levels of internalized homophobia, either by downplaying the experiences or invalidating your own identity can increase, which Stray (Citation2017) suggests is as a result of growing up in a heteronormative society. The Sussex Hate Crime Project found instances of online hate were linked to particular emotional and behavioral responses (Paterson et al., Citation2018). Viewing hate online can generate feelings of anger and anxiety, which produces either help-seeking responses (e.g. discussing and reporting online abuse) or avoidant behaviors (e.g. ignoring the abuse, social withdrawal) (Paterson et al., Citation2018). This is supported by Galop’s research in which some respondents reported an increased determination to engage in activism (Hubbard, Citation2020).

There exists very little research looking specifically at the effects of LGBTQ+ online hate on young people, despite an understanding that LGBTQ+ youth are exposed to more hate, and that young people typically experience more adverse effects than older cohorts (Keipi et al., Citation2016; UK Council for Child Internet Safety (UKCCIS),), Citation2017). General research has demonstrated that LGBTQ+ youth have an elevated risk for suicide and self-harm and mental health problems (McDermott, Citation2015). Cooper and Blumenfeld (Citation2012) carried out a small US study on LGBTQ+ online hate with 250 participants. 56% of participants had experienced depression and 35% had suicidal thoughts as a result of their experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate. Most experienced a range of behavioral responses, altering their appearance and their day-to-day interactions with their peers. Consequently, research suggests that young people have a preclusion to a wide variety of coping mechanisms, ranging from emotional and behavioral reactions, which impact their mental health both positively and negatively.

The scholarship available demonstrates the illocutionary power of LGBTQ+ online hate to cause widespread harms (Williams, Citation2019). However, the majority of research is quantitative in nature and misses the lived experiences of those being exposed to hate content online. When distinguishing between hate speech and hate crime, we fail to see that the impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate do not differ according to the criminal severity of the act. This paper therefore seeks to engage with LGBTQ+ youth regarding their experiences of all forms of online hate. This paper showcases how online hate is damaging and addresses the gaps in the literature that fail to understand the range of significant impacts that LGBTQ+ young people experience. Consequently, this paper demonstrates the need for criminal justice changes that effectively widens the scope of State responsibility to respond to the LGBTQ+ online hate endemic.

METHODOLOGY

Recruitment and Participants

This research collected data from 175 LGBTQ+ individuals aged 13–25 using a survey, followed by 15 semi-structured interviews with 16- to 25-year-olds, as part of a wider doctoral study looking at LGBTQ+ online hate experiences, impacts, and expectations and experiences with support services. Survey data was collected between February and September 2020, via onlinesurveys.ac.uk. Interviews were carried out exclusively via zoom or phone call between April and June 2020. Participants were recruited predominantly from the UK (n = 155), owing to the CoVID-19 pandemic and global shutdown of many infrastructural access points. However, six other countries are represented: France (6.9%), USA (1.7%), Italy (0.6%), Germany (0.6%), Canada (1.2%) and Hong Kong (0.6%). displays the demographic analysis for the sample with regards to age, gender and sexual orientation.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Participants were recruited through a number of avenues. The LGBTQ+ population are considered hidden and when accessing hidden populations there is a lack of clear sampling frames (Sulaiman-Hill & Thompson, Citation2011). Snowball sampling offered the best method to locate participants, and to enrich data quality. Subsequently, the primary pool of participants referred the research to their LGBTQ+ peers, either through word of mouth, or by sharing the survey link across their social media platforms, creating a snowball effect as they proposed other participants whose experiences and characteristics were relevant to this research (Bryman, Citation2016). As predicted by Kosinski et al. (Citation2015) this positive feedback loop led to a self-sustaining recruitment process, with a rapid growth in sample size.

This research also engaged with new and emerging recruitment methods. Social media platform advertisements have become widely regarded as useful tools for participant recruitment in social science research (see: Wozney et al., Citation2019; McRobert et al., Citation2018; Kosinski et al., Citation2015). This body of research informed this study’s use of social media advertisements, by adding a useful way to target hard to reach populations. The Facebook and Instagram Ads tool allows you to selectively recruit participants based on targeted demographic information, social interactions and user behaviors (Kosinski et al., Citation2015). Facebook and Instagram Ads were utilized specifically given that Facebook is used by over two and a half billion people globally every month (Omnicoreagency.com, Citation2020a) and Instagram is accessed by one billion users a month (Omnicoreagency.com, Citation2020b). Furthermore, 72% of teenagers use Instagram, whilst 30% of global Instagram audiences were aged between 18 and 24 years (Omnicoreagency.com, Citation2020b). Meanwhile, Facebook is accessed by 88% of online users aged 18–29 (Omnicoreagency.com, Citation2020a). A recent blog by Kemp (Citation2019), a chief analyst for DataReportal, estimated that the potential reach for advertising on Facebook is 113.3 million 13 to 17-year-olds, and 52.9 million on Instagram. This speaks to the success of using social media ads and is certainly reflected in their use for this research project, which saw an increase of 97 further survey responses over a four-week ad campaign.

The survey and follow-up interviews explored the nature and impact of LGBTQ+ young people’s experiences of online hate, and their experiences and expectations of support services, including, but not limited to criminal justice and social media platform responsibilities. In both instances questions were predominantly open ended, to allow LGBTQ+ voices to be centered. The survey and interviews were comprised of 3 sections - A: nature of LGBTQ+ online hate; B: experiences of support services; C: expectations of support services. This article focuses on a subsection of findings from Section A, detailing the relative harms of LGBTQ+ online hate on young people. It is not within the remit of this paper to discuss ongoing difficulties in defining and measuring online hate. Indeed, it is for this very reason that online hate was not defined to allow participants a free narrative to describe their experiences. To define online hate is to strategically or accidentally omit key victimization experiences (Powell et al., Citation2020). The interplay and overlap between what ought to be considered a spectrum of hate experiences highlights how research which treats such concepts as mutually exclusive has failed to provide an all-encompassing understanding of the true nature of online hate. By clearly demarcating LGBTQ+ online hate as a subjective concept, the contributions this paper will make to the field are clear in terms of understanding the lived realities and impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate and thus, the need for a more nuanced, meaningful response with respect to support, policy and prevention.

The data was analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s thematic analysis (Clarke et al., Citation2015). When exploring emotions and lived experiences there is no objective truth, therefore an inductive approach to thematic analysis was used (Terry et al., Citation2017). It was important that this stage of data analysis was inductive, as the themes needed to arise from participant experiences, opinions, behavior and practices, rather than preexisting assumptions regarding LGBTQ+ online hate (Clarke et al., Citation2015; Terry et al., Citation2017). A highly useful approach to data analysis, this centered the lived experiences and opinions of the LGBTQ+ community in defining the parameters of hate online, and to truly understand the impacts of online hate, and how they interact within their social worlds as a result. This presented an opportunity to acknowledge the discrete incidents individuals experience based on their relative socio-demographic circumstances and the norms and influences of the societies in which they live (Takács & Szalma, Citation2020). By using such a participatory research approach (Kindon et al., Citation2007; Bagnoli & Clark, Citation2010) this study allowed for an equitable collaboration process. This is reflected in the data analysis, and the achievement of a more “relevant,” morally aware, and nonhierarchical piece of research (Fuller & Kitchen, Citation2004; Pain, Citation2004).

DISCUSSION

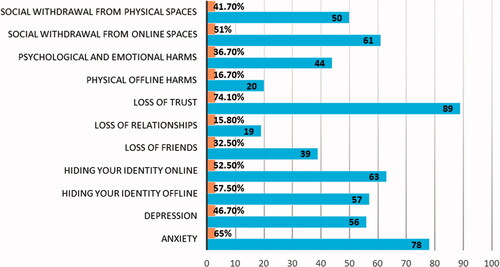

The results of this study indicate that LGBTQ+ young people are negatively affected by experiences of online hate in ways similar to research detailing the impacts of offline hate (Stray, Citation2017; Williams, Citation2019). The strength of the qualitative data procured from this study highlights some key impacts, brought to life by respondents’ own narratives, as their experiences are predominantly directed by free-text responses. 110 people described how their experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate made them feel, and a further 47 went into further detail after being prompted by an exemplar list of common impacts, based upon current literature (Stray, Citation2017; Williams, Citation2019). 120 participants engaged with the multiple-choice question detailing the effects of LGBTQ+ online hate (). However, the rates at which LGBTQ+ young people experience harms as a result of their experiences of online hate is compounded by unique identity factors. Before proceeding with the qualitative data exploring the impacts of online hate, it is important to recognize the prominence of the intersectionality of identity and double-edged hate directed toward LGBTQ+ people. An important finding from this research suggests a person’s gender compounds with their sexuality on rates of reported impacts following experiences of online hate. The following compare the rates at which cisgender males, cisgender females and transgender participants reported rates of anxiety, loss of trust and feelings of safety (consequently resulting in person’s hiding their identity both on and offline), as the most commonly reported impacts in .

Figure 1. Shows the effects of LGBTQ + online hate and the number of participants reporting each effect.

Table 2. Crosstabulation and chi-square test analysis of gender and anxiety.

Table 3. Crosstabulation and chi-square test analysis of gender and loss of trust.

Table 4. Crosstabulation and chi-square test analysis of gender and hiding identity online and offline.

The observed rates of anxiety for female and trans participants in were different to what we would have expected by chance. This demonstrates that females are over-represented in the not anxious category and trans participants are over-represented in anxious category. This finding contradicts what we usually expect to find, where rates of anxiety in LGBTQ+ females is typically higher (for example see Gillig & Bighash, Citation2021). The chi-square tests were run to explore the differences between what was observed and expected. They confirm the difference between the expected and observed rates is statistically significant (χ2 = 9.134, df = 2, p=.010). Similar statistically significant results were found for experiences of trust (or lack thereof) and experiences of hiding identity online and offline beyond what is expected by chance ( and ). According to the data presented in , once again, the observed and expected counts for female and trans participants differ by a considerable amount. This demonstrates that females are over-represented in the no loss of trust category and trans participants are over-represented in the loss of trust category. The observed and expected counts of males roughly approximate each other, which demonstrates that males are more or less equally represented in retaining trust and experiencing loss of trust as a result of experiences of online hate. The chi-square tests also confirm the difference between the variables is statistically significant (χ2 = 7.467, df = 2, p=.024). Finally, according to the data in , the observed and expected counts of the data for females and trans participants differ by a considerable amount. This demonstrates that females are over-represented in the not hiding their identity category and trans participants are over-represented in the hiding their identity category. The chi-square tests also confirm the difference between the variables is statistically significant (χ2 = 6.192, df = 2, p=.045). Therefore, the null-hypothesis is rejected; thus, there is a statistically significant difference between the rates at which different genders experience anxiety, loss of trust and a need to hide their identity following experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate. Consequently, the research suggests when we are exploring the impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate, a recognition of a person’s gender identity is also necessary to understand the ways aspects of our identity intersect to contribute to experiences of effects as a result of LGBTQ+ online hate. This point ought to be considered and adjusted for during quantitative and qualitative analysis.

Having established the differing rates at which LGBTQ+ young people experience adverse effects as a result of LGBTQ+ online hate, this paper now focuses on expanding our qualitative knowledge of the impacts. The qualitative efforts within this research highlight two important points. First, clearly in evidence are a wide range of impacts that transcended the severity or frequency of hate incidents experienced. Second, whilst a large number of individuals shared their experiences freely, the disparity between rates of effects reported within and subsequent qualitative excerpts shows a disconnect between our quantifiable understandings of the impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate, and the raw, lived experiences required to truly understand these effects. This disconnect ought to be kept in mind when working with vulnerable populations and the emotional labor needed to engage in research such as this. Also, to proceed with caution when merely looking at LGBTQ+ online hate from either solely a quantitative or qualitative viewpoint. With these points in mind, the qualitative findings from the survey and interviews are broadly categorized into some key topical effects: well-being effects, and relationships and social interactions.

Well-Being Effects

The first theme to be discussed are the negative effects on well-being reported by research participants. When describing how their experiences and observations of LGBTQ+ online hate made them feel, LGBTQ+ young people reported feeling a range of emotions, often comorbidly, including but not limited to sadness and depression, shame, inferiority, and behavioral responses such as social withdrawal.

Sadness and Depression

One of the most common emotions expressed were feelings of sadness and depression. 39 individuals reported varying levels of dejection within their free-text responses. Responses including words such as “upset,” “sad,” “hurt” and “depressed” were extremely common. Multiple studies have recorded elevated rates of depression in LGBTQ+ individuals, with a potential motivating factor being experiences of marginalization and discrimination (Cooper & Blumenfeld, Citation2012; Stray, Citation2017). These elevated levels of depression were self-disclosed by a number of participants,

The impact on the depressive state, I can confidently say, is absolutely evident. It has contributed to the isolated feeling and extremely low self-worth that accompanies that in a very specific and targeted way

Respondent #64, asexual, trans male, 22–25

While I do not believe that LGBTQ+ online harassment was the primary cause of any of my difficulties or diagnoses. I can definitely state that online hate based on my sexual orientation has affected my mental state, to the point that my psychiatrist started me on antidepressants

Respondent #73, pansexual, male, 18–21

Thus, experiences of online hate have a profound impact on one’s mental health. These examples illustrate how experiences of poor mental health already evidenced in young people, can be exacerbated by identity-targeted discrimination. Other participants expressed sadness that hate motivated by a person’s sexuality or gender identity still exists in today’s societies,

[I was] upset that people actually think that, I guess I’d thought maybe people weren’t as bad until I started getting comments saying that being gay is wrong

Respondent #95, asexual, queer, agender, non-binary, 13–15

Broader underlying systems of oppression and marginalization within the fabric of society have long been recorded as motivating factors for bias and hate (Alorainy et al., Citation2019; Leets, Citation2002; Perry, Citation2001). Power relations play a marked role in experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate, as the ingroup-outgroup dynamics of society breed the idea of status and a hierarchy of “normative” and “non-normative” sexualities and genders (Leets, Citation2002), despite desires to diversify understandings that all sexualities and genders are natural. An awareness of difference, and the tension created by dominant understandings of normal, universal identity categories (Welzer-Lang, Citation2008), has pervaded LGBTQ+ young people’s perceptions of how gender and sexuality should look. This point will be returned to in greater detail when we explore feelings of inferiority and invalidity.

Shame and Self-Blame

Participants reported an evolving sense of shame and self-blame, born out of experiences of depression and sadness. This followed a period of forced introspection in which the object of blame was their own identity, rather than any fault lying with the perpetrators,

It has somewhat reinforced some of the initial feelings I had prior to discovering that asexuality was "a thing" in thinking that I am broken

Respondent #64, asexual, trans male, 22–25

This shame and self-blame is palpable through the majority of young people’s responses. Between the ages of 13 and 25 we know individuals undergo a critical time of self-exploration, as they navigate understanding their identities and how they fit into the social world around them (De Ridder & Van Bauwel, Citation2015). When social cues from this world are invalidating their sense of identity, impressionable and unsure young people can internalize this.

It has caused negative feelings towards myself, where I feel ashamed or upset for being myself, where I have felt like I have to hide or change my identity. Where I have specifically tried to come across as straight or "straight passing" in order to avoid confrontation

Respondent #73, pansexual, male, 18–21

This sense of shame develops into a marked sense of inferiority, in which hierarchies of identity are reinforced by those being marginalized.

Feelings of Inferiority and Invalid Identities

One of the motivations behind hate crimes are to reinforce this hierarchy of identity, in which the most marginalized remain oppressed and ostracized (Perry, Citation2001). Reports of inferiority and expressions that their identity is invalid speaks to the so-called success and power of LGBTQ+ online hate perpetration. We can see the role social dominance theory plays in rules on identity (Sidanius & Pratto, Citation2001) and LGBTQ+ young people’s awareness of this,

It wasn’t until I got to school, puberty and there was all that social pressure and expectations from other people that and I thought ‘hang on am I not normal, am I supposed to be a girlygirl and go with boys’, so for me it was a wakeup call and a bit of a shock that people aren’t just going to accept me as I am, and I’m maybe not safe at this school, in this small village where nobody else is like me

Interviewee RT, pansexual, trans male, 22–25

LGBTQ+ young people feel an inordinate amount of pressure to assimilate to the dominant identity categories within society, rather than meeting their own needs for self-expression. All these experiences continue to reinforce the social hierarchy boundaries already in place. Self-blame and feelings of inferiority were often intertwined, affecting an individual’s understanding of gender and sexuality, thus creating a sense that there’s a right or wrong way to be. The power and privilege afforded to dominant groups is displayed in LGBTQ+ young people’s desires to conform, rather than embrace their difference (Sidanius & Pratto, Citation2001).

Like I was a terrible person and that I was disgusting, and I didn’t know how to think of myself anymore and I considered just “acting straight” to avoid it all

Respondent #115, pansexual, female, 13–15

Made me feel like being LGBT + was wrong morally & spiritually and that I should hide that part of myself if I want to feel accepted

Respondent #67, gay, queer, male, 22–25

Feeling like there is something immoral regarding your own identity is bound to have a marked effect on your mental well-being as evidenced by respondents reporting an increase in depression and anxiety alongside these feelings of shame and inferiority. The effects on LGBTQ+ young people’s mental well-being then, is far more complex than categorizing according to depression, sadness, and anxiety on its own. An understanding of the power structures and hierarchical systems that make up society are critical to understand how an individual develops their sense of self and as a result navigates the social world (Leets, Citation2002). This is the next theme to be discussed in terms of the behavioral changes implemented by LGBTQ+ young people to mitigate mental well-being effects and minimize future victimization.

Relationships and Social Interactions

The second and most consistent theme to arise from the data were the profound effects LGBTQ+ online hate had on young people’s relationships and social interactions. Respondents reported a marked change in how they navigated their social worlds, with an overwhelming need to hide their identity both online and offline. These changes in behavior are used to mitigate and protect from future victimization experiences. Respondents reported a heightened lack of safety and loss of trust in both friends and strangers, thereby causing increased rates of isolation and withdrawal from both online and offline spaces. Thus, experiences of online hate drastically impacts both the emotional and physical well-being of an individual, as well as their liberty and rights to occupy certain social spaces (Perry & Alvi, Citation2012). As highlighted in the previous section, LGBTQ+ online hate has a profound impact on an individual’s sense of self-worth, and by withdrawing from both geographical and virtual spaces, reinforces the marginalization and otherness of LGBTQ+ young people.

Fear and Lack of Safety

Through repeated exposure to LGBTQ+ online hate, participants reported heightened levels of fear. 21 participants used the terms “fear,” “scared,” “terrified” or “frightened” to describe their experiences in some way. Fear is reported to be one of the main intentions of hate (Awan & Zempi, Citation2016; Perry & Alvi, Citation2012), and this research is the first detailed report of fear manifesting in LGBTQ+ youth as a result of online hate. The anonymity of the online world amplified the fear effect in respondents, who were often unable to identify the perpetrators of hate. This manifested in feeling helpless and paralyzed,

[I have a] fear of online hate comments every time I post something now

Respondent #56, queer, pansexual, female, 18–21

Continually respondents demonstrated that the effects of LGBTQ+ online hate do not stay isolated to the online world, but filter into all aspects of a person’s life. Respondents reported fear for their physical well-being, and the physical well-being of their LGBTQ+ peers. As identified within the literature, such is the nature of hate as a message crime, targeting LGBTQ+ identity as a whole and anyone who belongs to the identity group (Paterson et al., Citation2018). One respondent described this experience as,

From incidents I have witnessed I feel angry and upset and also scared. I feel safe because I am a bisexual woman who is in a heterosexual relationship and is not openly out as bi so I do not feel like I will be targeted but I feel angry and upset and scared for the people who don't fly under the radar like me

Respondent #5, bisexual, female, 22–25

Thus, visible difference is correlated with perceived vulnerability to hate as well as empathy toward other potential victims. The care and comradery felt by LGBTQ+ young people show how acutely aware they are that their gender and sexuality is the object of hate, discrimination and marginalization. We see this expressed in perceptions of how conformity to the norm of cisgender and heterosexuality offers certain levels of protection from hate, as suggested by the data in which trans participants are over-represented in hiding their identity as a result of hate experiences. The safety experienced within conformism is a powerful influencer on LGBTQ+ young people wishing to avoid hate. Overall patterns in the data show LGBTQ+ young people report that feelings of fear led to feeling unsafe in expressing their true identity to others.

I really feel like I lack any form of trust with others, I can easily detach now. I don’t like spending much time with other people nor do I actively try to promote myself as LGBT+. If I do tell someone, they end up judging me (from my pov)

Respondent #113, bisexual, pansexual, female, gender-fluid, 16–17

This lack of trust is deeply embedded in the majority of respondents’ associations with others. Perceptions of a hierarchy of identity amplified difference as a vulnerability to be hidden. Moreover, the lack of trust expressed by participants manifested as a skepticism of the safety of society as a whole. A combined mistrust of social players and social leaders highlights a power play embedded within the fabric of society as a contributing factor responsible for upholding hierarchical identities,

It honestly proves the view that we have not progressed in any way as a civilization or a people, people are still horrible, and this is not a safe world to be in if you are different. It does make you more cynical overall

Respondent #22, gay, male, 22–25

It’s rarely dealt with, even when reported. So, you start to realize that online there are no protections for queers or non cis people. Our only protection there is our own community

Respondent #8, lesbian, gay, queer, female, 22–25

Questioning how society fails to eradicate online hate and the continued marginalization of LGBTQ+ people deepened the sense of hopelessness accompanying respondents’ fear to take up space in mainstream society. This sentiment is encapsulated in a question of “if society will not protect you, who will?” Thus, the emotional impacts of sadness, shame and fear develop into behavioral changes that limits the liberty and mobility of LGBTQ+ young people in both online and physical spaces; the next theme to be discussed within this study’s findings.

Isolation and Withdrawal from Online/Offline Spaces

Perhaps due to heightened feelings of fear and losing trust in the availability of safe spaces, many participants reported an overwhelming sense of isolation. Consequently, faced with the possibility of having to constantly safeguard in potentially threatening environments, LGBTQ+ young people chose to withdraw from the online and offline world. This supports findings from Perry and Alvi (Citation2012) that in order to avoid future experiences of hate, LGBTQ+ young people develop strategies to negotiate their safety. Many respondents described these behavioral changes as necessary; such were the dangers of occupying certain spaces as openly LGBTQ+. These changes in routine activities and expressions of identity are shared in some of the most detailed responses,

It made me not want to talk to anyone online. My mental health deteriorated, and I didn't trust anyone (whether online or offline) enough to talk to them about it. I now get anxiety talking to other people online and I usually hide my sexual orientation and gender identity for as long as I can

Respondent #130, fluid-sexuality, trans male, 16–17

The experience of continually having to "hide" my queerness online is a constant feeling of looking behind my shoulder in a sense and being overly careful online. I often do not go on Facebook because of this, and use other sites such as Twitter to share my true self

Respondent #44, queer, female, 22–25

Reports of behavioral changes are often comorbid with reports in deterioration of mental well-being. The emotional harms of LGBTQ+ online hate, and the relative unsafety and lack of LGBTQ+ friendly spaces, limit the choice of viable coping mechanisms. The question of safety is ongoing, as respondents reported a continual change to their behavior online and offline. The use of avoidant behaviors offline shows how the impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate does not stay within the confines of the online platform in which it occurred. The perception of danger and fear of further victimization is such that most respondents reported a blanket withdrawal from all social spaces, as opposed to just those where the hate experiences occurred,

I left social media and spent most of my time alone

Respondent #34, gay, male, 22–25

I couldn’t tell my parents what was happening because I wasn’t out to them because they’re very LGBT-phobic. I’d stay in my room for days binging Netflix and sleeping. My friends would try to contact me, but I would decline their calls or ignore their messages. And I wouldn’t come downstairs for days at a time

Respondent #79, questioning, non-binary, 13–15

The impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate are neither isolated, nor short term, but permeate into a person’s whole life, even when their sexuality is not contextually relevant. An incident of online hate targeting your sexuality or gender identity has the illocutionary power to affect your perceptions of how the entire world will view you (Williams, Citation2019). With something so personal, caution, fear and mistrust of repeat episodes of rejection are enough to amplify the negative mental health effects. Thus, creating a vicious cycle between fear of safety, loss of trust and social withdrawal. Moreover, there were no significant differences in reports of behavioral changes between participants who were the direct target of an online hate incident and those who observed online hate.

I’ve been diagnosed with social anxiety for a while but receiving and observing hate online made me anxious to come out and be honest about who I am. I’ve also wanted to avoid social media because of the hate against LGBT people I see even when it isn’t directed at me

Respondent #138, lesbian, female, 13–15

The near constant exposure to anti-LGBTQ+ sentiment and subsequent withdrawal from spaces which continue to host this hate reinforces the “us versus them” binary reported in anti-Muslim hate crime research (Awan & Zempi, Citation2016). By strengthening the idea of the “other” and preventing interactions between different identities and communities, we see how behavioral changes as a result of online hate can harbor a system of resentment, fear and ostracism between both the LGBTQ+ community and the cisgender, heterosexual community.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

This study contains some limitations which should be considered alongside an understanding of the findings. First, as highlighted within the methods section, the sample largely comes from the United Kingdom, therefore it is unclear if experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate differs depending on the home State of the person. However, as the internet is a world without borders (Yar & Steinmetz, Citation2019), research suggests the reach of online hate is far greater than its offline counterpart. Moreover, as discussed, it is the responsibility of criminal justice agencies to develop multilateral responses to online hate. Given the geographic indeterminacy of the internet, it is reasonable to argue that the physical location of a person is more relevant to problems of jurisdictional rights as opposed to likelihood of being victimized (Banks, Citation2010). Additionally, as a qualitative piece of research, each person’s experiences of LGBTQ+ online hate are simultaneously considered to be true and valid. Whilst this is a strength of this research in understanding the complex and multi-faceted nature of experiences of online hate, one must take caution in trying to apply a universal framework to this study. As discussed, there are limits to these frameworks themselves, given a lack of universal understanding of online hate. But nonetheless an objective framework would be useful to investigate the potential differing rates at which LGBTQ+ individuals of diverse genders, sexualities and ages experience online hate. Therefore, further quantitative research is needed to explore experiences of online hate within an international sample.

On the point of sample size, this study attempted to recruit participants using snowball sampling. No study is entirely free from bias, and whilst this research achieved a diverse sample in terms of gender, sexualities and age, participants were predominantly UK based and from white backgrounds. The lack of ethnic and racial diversity within the sample is likely due to the restricted conditions through which the data collection was carried out. As previously mentioned, the research was solely carried out through the first few months of the Coronavirus Pandemic and international lockdowns. A lot of infrastructural access point were closed, therefore the sample pool was very much restricted in its reach. Every piece of research into identity must consider how identity is intersectional.

Furthermore, this research attempted to understand the intersections between a person’s gender and sexuality on impacts of LGBTQ+ online hate. It is important to recognize that gender is a fluid concept, and therefore a number of participants identify with more than one gender label (e.g. female and genderfluid). When carrying out statistical tests, to analyze the full cohort of participants, gender has to be treated as nominal. Within each potential gender category, there existed unstable cells due to small participant numbers. Thus, to run the tests, overarching categories were created between genders (cisgender female, cisgender male and trans participants). This resulted in an overhaul of the nuance of gender and may undermine the true relationship between gender and sexuality. Moreover, there was a much lower proportion of participants identifying as male than female and transgender, which is unexpected given population frequencies (Antjoule, Citation2016; Office for National Statistics, Citation2020). Therefore, this could induce possible biases in the data. To further understand the relationship between the intersections of identity, a larger sample size is needed to successfully run the statistical tests between every possible gender category. Therefore, future research is needed to determine how the intersections of gender, race, religion, ethnicity, and other aspects of a young person’s identity intersect to contribute or exacerbate their marginalization experiences.

CONCLUSION

This paper explored how LGBTQ+ online hate impacts young people beyond what we currently know from quantitative research. This study revealed that online hate is damaging, producing a range of significant emotional and behavioral responses in LGBTQ+ young people, in particular reports of sadness, shame, and feelings of inferiority. LGBTQ+ young people develop an internalized sense of blame for their victimization and seek to assimilate to the dominant identity categories within society, unable to safely express their own gender or sexuality. This perceived lack of safety permeates through most participants’ responses, producing long-term behavioral changes. LGBTQ+ young people have developed coping strategies for navigating the social world which largely consists of opting out of participating in society altogether. Respondents reported how their withdrawal limited opportunities for identity-building and peer development. As critical aspects of a young person’s development, and the importance of the online world as a vehicle for this, we can see how online hate has a profound impact, affecting a person’s life online, offline, as well their relationships with themselves and with others (De Ridder & Van Bauwel, Citation2015).

It is clear from this research, that given the multifaceted, complex effects of online hate, responses similarly need to be multidimensional. Currently, our focus in responding to online hate lies solely within criminal justice pathways. Whilst responses to combatting online hate need to go beyond the punitive aspects of criminal law, the law has a significant role to play in responding to such conduct (Barker & Jurasz, Citation2018). However, this paper demonstrates that a failure to provide provisions for a comprehensive understanding of hate speech in any legal definition, precludes our ability to appropriately respond to online hate. This paper’s findings clearly demonstrate that online hate has tangible impacts that restrict liberty, causes isolation, and is detrimental to LGBTQ+ young people’s mental health and physical well-being. Moreover, when experienced during childhood and critical periods of youth development, they can increase the likelihood of school dropout, chemical dependency and abuse, homelessness, and other types of instability during adulthood (Ecker et al., Citation2020; Keuroghlian et al., Citation2014; Subhrajit, Citation2014; Gwadz et al., Citation2004). Thus, the full spectrum of online hate should be taken more seriously through legal definitions and by criminal justice agencies to avoid future reliance on and relationships between criminal justice agencies and LGBTQ+ young people.

A harms approach to online hate recognizes the role of criminal law within the social world. LGBTQ+ people are entitled to rights and justice, not just symbolic protections (Perry, Citation2008). An understanding of the tangible impacts on LGBTQ+ people’s lives can shape the law into a cohesive framework to successfully protect its citizens from the complex nature of online hate. Where currently the law is failing to appropriately respond to online hate lies within its failure to recognize that the harms of hate are a problem for social and legal justice (Siegel, Citation2020). This paper recommends that a legal definition of hate speech that is inclusive of harm serves to afford LGBTQ+ people the respect and rights of equal citizenship, but also expands our understandings of hate motivation and online hate to target all forms of discrimination within society (Perry, Citation2008). Consequently, as Perry (Citation2008) argues, such a reformation of criminal justice frameworks demonstrates the perceived cultural value of a marginalized group as both the target of and remedy for oppression. This has a redistributive effect to transform cultural attitudes as the law shapes behaviors and understandings of sexuality and gender identity (Wigerfelt et al., Citation2015).

This paper recognizes that not all instances of hate will require a criminal justice response. Further input from support agencies, online platforms, and other institutions responsible for the well-being of children and young adults are also needed to develop a holistic approach to supporting LGBTQ+ young people. Banks argues that such a coalition of multilateral efforts will be most effective in reducing the harm caused by hate online (Banks, Citation2010). As we have seen, online hate that does not amount to a crime still has a profound impact on the lives of LGBTQ+ young people. With such extreme emotional, psychological, and physical adverse effects, there is convincing evidence of the need for services to offer support to victims of all forms of online hate. Therefore, criminal justice agency responsibility is twofold (Barker & Jurasz, Citation2018). Primarily, criminal justice agencies need to widen the scope of which online hate incidents are considered criminal offenses. However, they are also responsible for increasing regulation and greater liability for online platforms hosting this hate. Therefore, where an incident of does not reach the threshold for criminal culpability, online service providers ought to be made more accountable for maintaining safe online environments free from hate and harm. Yet, research suggests that inconsistent responses from the law, social media platforms, internet providers and support services convey the impression that hate that is not criminal in nature is not serious enough to warrant a response (Hardy & Chakraborti, Citation2020). A shift toward a more cohesive, relative understanding of online hate, alongside a rejection of the assumption that what occurs online is neither harmful, nor serious in nature, would begin to mend the mistrust between the LGBTQ+ community, authorities, and wider communities. Therefore, this study acts as a stepping stone and a justification for future research to explore a targeted response to all forms of online hate with respect to social support, policy changes and prevention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to the research participants for their time and honesty when talking about such an emotional topic. Also, thanks to Professor Neil Chakraborti and Professor Teela Sanders, whose support and comments on earlier drafts proved invaluable. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Rachel Keighley. The data is not publicly available due to the thesis being ongoing and their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

REFERENCES

- Alorainy, W., Burnap, P., Liu, H., & Williams, M. (2019). The enemy among us: Detecting hate speech with threats based 'othering' language embeddings. ACM Transactions on the Web, 13(3), 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/3324997

- Antjoule, N. (2016). The hate crime report 2016 [online]. Galop, pp. 1–35. Retrieved September 01, 2021, from http://www.galop.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/The-Hate-Crime-Report-2016.pdf.

- Awan, I., & Zempi, I. (2016). The affinity between online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime: Dynamics and impacts. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 27, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.02.001

- Bachmann, C., & Gooch, B. (2017). LGBT in Britain: Hate Crime and Discrimination. Stonewall.

- Bagnoli, A., & Clark, A. (2010). Focus groups with young people: a participatory approach to research planning. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(1), 101–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903173504

- Banks, J. (2010). Regulating hate speech online. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 24(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2010.522323

- Barker, K., & Jurasz, O. (2018). Online violence against women: The limits & possibilities of law. Stirling Law School & Open University Law School. http://oro.open.ac.uk/53637/1/OVAW%20-%20The%20Limits%20%26%20Possibilities%20of%20Law%20%282018%29.pdf

- Brandwatch and Ditch the Label. (2016). Cyberbullying and hate speech. Brandwatch.

- Brandwatch and Ditch the Label. (2019). Transphobia report 2019. Brandwatch.

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Chakraborti, N. (2018). Responding to hate crime: Escalating problems, continued failings. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 18(4), 387–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817736096

- Chakraborti, N., & Hardy, S. J. (2017). Beyond empty promises? A reality check for hate crime scholarship and policy. Safer Communities, 16(4), 148–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/SC-06-2017-0023

- Clarke, V., Braun, V., & Hayfield, N. (2015). Thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, (3rd ed.), pp. 222–248.

- Cooper, R. M., & Blumenfeld, W. J. (2012). Responses to cyberbullying: A descriptive analysis of the frequency of and impact on LGBT and allied youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 9(2), 153–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2011.649616

- Council of Europe. (1997). Recommendation, No. R., (97) 20 of the committee of ministers to member states on “hate speech. Council of Europe [online]. Retrieved August 03, 2021, from https://rm.coe.int/1680505d5b.

- Council of Europe. (2020). Freedom of expression: Guide on Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights, August 2020, ECHR. [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Guide_Art_10_ENG.pdf.

- CPS (Crown Prosecution Service). (2019). Hate crime annual report 2018–19. Crown Prosecution Service [online]. Retrieved August 07, 2021, from https://www.cps.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/publications/CPS-Hate-Crime-Annual-Report-2018-2019.PDF.

- De Ridder, S., & Van Bauwel, S. (2015). The discursive construction of gay teenagers in times of mediatization: youth's reflections on intimate storytelling, queer shame and realness in popular social media places. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(6), 777–793. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.992306

- Ecker, J., Aubry, T., & Sylvestre, J. (2020). Pathways into homelessness among LGBTQ2S adults. Journal of Homosexuality, 67(11), 1625–1643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1600902

- FBI. (2019). Hate crime statistics 2019. US Department of Justice.

- FRA. (2018). Hate crime recording and data collection practice across the EU. European Union Agency for Fundamental Human Rights.

- Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA. Framework decision on combating certain forms and expressions of racism and xenophobia by means of criminal law. (2008), OJ L 328 of 6.12.2008. EU Lex [online] https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=LEGISSUM:l33178.

- Fuller, D., & Kitchen, R. (2004). Radical theory/critical praxis: academic geography beyond in the academy? In D. Fuller and R. Kitchen (Eds.), Radical theory/critical praxis: Making a difference beyond the academy? (pp.1–20). Praxis (e)Press.

- Gillig, T. K., & Bighash, L. (2021). Network and proximity effects on LGBTQ youth’s psychological outcomes during a camp intervention. Health Communication, 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.1958983

- GLSEN, CiPHR, and CCRC. (2013). Out online: The experiences of Lesbian. Gay, bisexual and transgender youth on the internet. GLSEN.

- Guasp, A., Gammon, A., & Ellison, G. (2013). Homophobic hate crime: The gay British crime survey 2013 (pp.1–32). Stonewall.

- Gwadz, M. V., Clatts, M. C., Leonard, N. R., & Goldsamt, L. (2004). Attachment style, childhood adversity, and behavioral risk among young men who have sex with men. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 34(5), 402–413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00329-X

- Hardy, S. J., & Chakraborti, N. (2020). Blood, threats and fears: The hidden worlds of hate crime victims. Springer Nature.

- Home Office. (2020). Hate crime, England and Wales, 2019/20. Home Office, Crime and Policing Statistics.

- Hubbard, L. (2020). Online hate crime report 2020 [online]. Retrieved August 04, 2021, from Galop. http://www.galop.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Online-Crime-2020_0.pdf.

- Jones, L. M., Mitchell, K. J., & Finkelhor, D. (2013). Online harassment in context: Trends from three youth internet safety surveys (2000, 2005, 2010). Psychology of Violence, 3(1), 53–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030309

- Keighley, R. (2022). The dark side of social media: Exploring the nature, extent, and routinisation of LGB + online hate [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. University of Leicester.

- Keipi, T., Näsi, M., Oksanen, A., & Räsänen, P. (2016). Online hate and harmful content: Cross-national perspectives. Routledge.

- Kemp, S. (2019). Over 3.5 billion people are on social media; Facebook still biggest with teens; Esports on the rise. Podium. Retrieved May 14, 2021, from https://thenextweb.com/podium/2019/07/17/over-3-5-billion-people-are-on-social-media-facebook-still-biggest-with-teens-esports-on-the-rise/>

- Keuroghlian, A. S., Shtasel, D., & Bassuk, E. L. (2014). Out on the street: a public health and policy agenda for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0098852

- Kindon, S., Pain, R. and Kesby, M., eds., (2007). Participatory action research approaches and methods: Connecting people, participation and place. Routledge.

- Kosinski, M., Matz, S. C., Gosling, S. D., Popov, V., & Stillwell, D. (2015). Facebook as a research tool for the social sciences: Opportunities, challenges, ethical considerations, and practical guidelines. The American Psychologist, 70(6), 543–585. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039210

- Leets, L. (2002). Experiencing hate speech: Perceptions and responses to anti‐semitism and antigay speech. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 341–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00264

- Marston, K. (2019). Researching LGBT + youth intimacies and social media: The strengths and limitations of participant-led visual methods. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418806598

- McDermott, E. (2015). Asking for help online: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans youth, self-harm and articulating the 'failed' self. Health, 19(6), 561–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459314557967

- McRobert, C. J., Hill, J. C., Smale, T., Hay, E. M., & van der Windt, D. A. (2018). A multi-modal recruitment strategy using social media and internet-mediated methods to recruit a multidisciplinary, international sample of clinicians to an online research study. PLOS One, 13(7), e0200184–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200184

- Myers, Z. R., Swearer, S. M., Martin, M. J., & Palacios, R. (2017). Cyberbullying and traditional bullying: The experiences of poly-victimization among diverse youth. International Journal of Technoethics, 8(2), 42–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/IJT.2017070104

- ODIHR. (2018). 2018 Hate crime data key findings. OCSE/ODIHR [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Infographics/2018-key-findin_updated%20Feb%202020.pdf.

- ODIHR. (2019). 2019 Hate crime data key findings. OCSE/ODIHR [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Infographics/2019/2019%20Key%20Findings%20UPDATED%20JAN%202021_PDF.pdf.

- Ofcom. (2018a). Adults’ media use and attitudes report [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/113222/Adults-Media-Use-and-Attitudes-Report-2018.pdf.

- Ofcom. (2018b). Children and parents: media use and attitudes report 2018 [online]. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/media-literacy-research/childrens/children-and-parents-media-use-and-attitudes-report-2018. Accessed 21 May 2021.

- Ofcom. (2019a). Adults: Media use and attitudes report 2019 [online]. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from Ofcom. https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0021/149124/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-report.pdf.

- Ofcom (2019b). Children and Parents: Media use and attitudes report 2019. [online] London: Ofcom. Retrieved May 01, 2021, from <https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/190616/children-media-use-attitudes-2019-report.pdf>

- Office for National Statistics. (2020). Population estimates. Office for National Statistics.

- Omnicoreagency.com. (2020a). Facebook by the numbers (2020): Stats, demographics & fun facts [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.omnicoreagency.com/facebook-statistics/.

- Omnicoreagency.com. (2020b). Instagram by the numbers (2020): Stats, demographics & fun facts [online]. Retrieved May 21, 2021, from https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/.

- Pain, R. (2004). Social geography: Participatory research. Progress in Human Geography, 28(5), 652–663. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132504ph511pr

- Paterson, J., Walters, M. A., Brown, R., & Fearn, H. (2018). The Sussex hate crime project (pp. 1–53). Sussex.

- Powell, A., & Henry, N. (2017). Sexual violence in a digital age. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Powell, A., Scott, A. J., & Henry, N. (2020). Digital harassment and abuse: Experiences of sexuality and gender minorities. European Journal of Criminology, 17(2), 199–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818788006

- Perry, B. (2001). In the name of hate: Understanding hate crimes. Routledge.

- Perry, J. (2008). The ‘perils’ of an identity politics approach to the legal recognition of harm. Liverpool Law Review, 29(1), 19–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10991-008-9034-9

- Perry, B., & Alvi, S. (2012). We are all vulnerable’ The in terrorem effects of hate crimes. International Review of Victimology, 18(1), 57–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758011422475

- Sellars, A. (2016). Defining hate speech (pp.16–48). Berkman Klein Center Research Publication.

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (2001). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press.

- Siegel, A. A. (2020). Online hate speech. In N. Persily & J. Tucker (Eds.), Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform (1st ed., pp. 56–88). Cambridge University Press.

- Stray, M. (2017). Online hate crime report 2017 [online]. Galop, pp. 1–27. Retrieved May 26, 2021, from http://www.galop.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Online-hate-report.pdf.

- Subhrajit, C. (2014). Problems faced by LGBT people in the mainstream society: Some recommendations. International Journal of Interdisciplinary and Multidisciplinary Studies, 1(5), 317–331.

- Sulaiman-Hill, C. M., & Thompson, S. C. (2011). Sampling challenges in a study examining refugee resettlement. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 11(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-11-2

- Takács, J., & Szalma, I. (2020). Democracy deficit and homophobic divergence in 21st century Europe. Gender, Place & Culture, 27(4), 459–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1563523

- Terry, G., Hayfield, N., Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. In: C. Willig & W. Stainton Rogers (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. (2nd ed., pp. 17–37).

- UK Council for Child Internet Safety (UKCCIS). (2017). Children’s online activities, risks and safety a literature review by the UKCCIS Evidence Group [online]. UKCCIS, pp. 1–106. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/759005/Literature_Review_Final_October_2017.pdf.

- UK Council for Internet Safety (UKCIS). (2019). Adult online hate, harassment and abuse: A rapid evidence assessment [online]. Gov.uk, pp. 1–131. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/811450/Adult_Online_Harms_Report_2019.pdf.

- Wall, D. ed., (2001). Crime and the Internet. Routledge.

- Welzer-Lang, D. (2008). Speaking out loud about bisexuality: Biphobia in the gay and lesbian community. Journal of Bisexuality, 8(1–2), 81–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15299710802142259

- Wigerfelt, A. S., Wigerfelt, B., & Dahlstrand, K. (2015). Online hate crime: Social norms and the legal system. Quaestio Iuris, 8(3), 1859–1878.

- Williams, M. (2019). Hatred behind the screens: A report on the rise of online hate speech. Hate Lab.

- Wozney, L., Turner, K., Rose-Davis, B., & McGrath, P. J. (2019). Facebook ads to the rescue? Recruiting a hard to reach population into an Internet-based behavioral health intervention trial. Internet Interventions, 17(100246), 100246–100246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2019.100246

- Yar, M., & Steinmetz, K. F. (2019). Cybercrime and society. SAGE Publications Limited.