Abstract

This article analyzes the impact that the sex of law enforcement officers might have on the way they intervene in Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) situations, and if that is determined by prejudices related to traditional gender roles within intimate relationships. A questionnaire was applied to 1,872 law enforcement officers of GNR (Republican National Guard), Portugal. The results show differences in beliefs and perceptions and subsequent decisions to intervene, which reveal that women and men hold different views about gender roles and IPV. The data warns against the influence that prejudices might have on the decision to act in IPV situations.

INTRODUCTION

In the last few years, Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) has come to the forefront in Portugal, especially after a series of women were killed by their partners. These cases garnered media attention, which led to greater public discussion and highlighted the need to look for more efficient ways of intervening to prevent and fight against this type of violence.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

Under Portuguese law, IPV does not constitute an autonomous crime and usually falls under the term “domestic violence,” which in article 152 of the Portuguese Criminal Code is defined more broadly, encompassing several types of relations and elements of the family unit. Nonetheless, given the specificity of the social and power relations at play in each of these situations of violence, it is crucial that their differences are taken into account. In an effort to focus our attention on the specific violence that arises within spousal and intimate relationships, we prefer to use the IPV concept.

By intimate partner we understand any person with whom close personal relationships were or are maintained, with emotional connection and physical and sexual contact, where the identity of a couple and the idea of familiarity are taken on, entailing a knowledge about the other person’s life, even though the relationship might not include all of these dimensions (Basile & Black, Citation2011; Breiding et al., Citation2015; Gordon, Citation2000; Harne & Raford, Citation2008).

IPV comprises different forms of aggression, namely physical, sexual, psychological, emotional or persecutory (FRA, Citation2014; Basile et al., Citation2011), even putting the victim’s life at risk (Harway et al., Citation2002). Besides the immediate impact on the victim’s physical integrity and health, IPV also entails discrimination and the violation of the victim’s fundamental rights and freedoms, which derive from a system of asymmetric gender relations, reproduced throughout history in accordance with patriarchal values (DeKeseredy, Citation2011; Dobash & Dobash, Citation2003; Dobash et al., Citation2007; Gordon, Citation2000; Lisboa et al., Citation2006, Citation2007, Citation2008). If we look at the complex social structures and mechanisms of interaction between the public and social spheres, we see an unequal distribution of power between men and women, which legitimizes the prevalence of authority as a valid expression of male identity (Enguix, Citation2020; Pérez-Martínez et al., Citation2021; Santos, Citation2020; Vieira, Citation2017, Citation2020).

In this context, several indicators show that IPV is mostly a crime committed by men against their intimate female partners (Basile & Black, Citation2011; Gordon, Citation2000; Torres et al., Citation2018). Not only does the number of female victims surpass that of male (EIGE, Citation2020; Erez, Citation2002; FRA, Citation2014; Harway et al., Citation2002; Torres et al., Citation2018). but the type of aggression inflicted on women tends to be more serious as well (Hanganu et al., Citation2017; Menjívar & Salcido, Citation2002; Wang, Citation2016). The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA, Citation2014) concluded that 22% of women (in past or current relationships with men) have been victims of physical and/or sexual violence. In Portugal, the data gathered by UMAR (OMA-UMAR, Citation2020) also shows that over half of murdered women were victims of femicide in the context of intimate relationships (current, past or desired).

The prevention and repression of IPV are concerns of contemporary judicial systems, with many countries forced to implement or develop reforms of their criminal justice system as a way of protecting people from violent intimate partners (Brown, Citation2001). Therefore, Brown mentions that there is a general preoccupation with training the police, prosecutors, and judges to counteract prejudice and ignorance (Brown, Citation2001). Even though there are different efforts and attempts to reduce the number of IPV victims, research shows that the results are below the expected (Birdsall et al., Citation2017).

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and Police Intervention

Police intervention is particularly important in the identification of IPV situations and the processing and support of victims (Day et al., Citation2018; Harne & Raford, Citation2008; Vigurs et al., Citation2016). In judicial systems such as the Portuguese, where domestic violence (which includes IPV) is a public-order crime, this intervention is even more crucial, since the beginning of criminal prosecution is not dependent on the victim’s complaint, nor can it cease if the victim decides to drop the case (Buzawa et al., Citation1998, Citation2000; Gracia et al., Citation2008; Holder, Citation2001; Sani et al., Citation2018).

Nonetheless, existing studies suggest that the denunciation of IPV to police authorities is below current occurrences (Cormier & Woodworth, Citation2008; Dowling et al., Citation2018; HMIC, Citation2015; Johnson et al., Citation2008; Ragusa, Citation2012). According to estimates, complaints represent between 2 and 52% of actual cases (Wolf et al., Citation2003). Birdsall et al. (Citation2017) refer to the need for a greater awareness and empowerment of victims, suggesting more investment in police action practices. Moreover, whenever the police handles the situation incorrectly this can reinforce feelings of victimization (secondary victimization) and condition the victim’s behavior regarding future acts of violence (Apsler et al., Citation2003; Fedina et al., Citation2019; Goodman-Delahunty & Crehan, Citation2016; Gracia et al., Citation2008; HMIC, Citation2015; Ragusa, Citation2012; Rich & Seffrin, Citation2012; Stover et al., Citation2010; Wolf et al., Citation2003). In fact, Birdsey and Snowball observed, for example, that 18% of the victims who did not report IPV were swayed by reasons related to police behavior, namely a bad or disappointing experience during previous complaints to the police (10.4%), or the belief that the police would not do anything (7.6%). When asked about their decision to not report, 17.1% of victims referred to the police’s lack of knowledge regarding IPV, or their lack of proactivity when dealing with this type of situation (Birdsey & Snowball, Citation2013). In this sense, the creation of broader and more flexible police intervention responses and different structures (with multidisciplinary teams), can be used proactively to promote a greater understanding of the victim, increase victim cooperation, and consequently obtain better results in criminal justice (Birdsall et al., Citation2017).

The level of discretion awarded to the police in the assessment of IPV cases, and the fact that police forces around the world tend to have relatively conservative attitudes on issues related to IPV, shows the relevance of police intervention (Ashlock, Citation2019; Gölge et al., Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2021; McMullan et al., Citation2010; Myhill & Johnson, Citation2016). In this context, it is necessary to study to what extent their work is determined by the beliefs they might have regarding IPV, the victims, and the aggressors, in line with what has been suggested by the scientific literature (Cormier & Woodworth, Citation2008; Gover et al., Citation2011; Gracia et al., Citation2011; Logan et al., Citation2006; Muftić & Cruze, Citation2014; Russell, Citation2017; Stalans & Finn, Citation2006; Trujillo, Citation2008).

Therefore, it is important to understand if the decision to intervene is associated with institutionalized models of police behavior based on previous experiences of intervention in similar cases or whether it may be determined by beliefs and prejudices that police officers have about IPV. For example, one should determine if the decision to detain the aggressor or not stems from a patriarchal organizational culture deriving from a predominantly male model of policing, or if it reflects personal prejudices regarding gender roles and entails a devaluing of violence against women in certain contexts.

Consequently, it is important to ascertain whether the sex of the law enforcement officer has an influence on the way they behave. If so, this could mean that the law enforcement officer’s duty to keep the law and protect the people is overshadowed by the individual socialization process, or that the whole institution is permeated with a patriarchal culture that shapes the type of approach and treatment given to IPV situations.

The scientific literature that has examined the influence of the gender variable on police intervention in IPV cases is not conclusive (Lockwood & Proshaka, Citation2015; Poteyeva & Sun, Citation2009), since some studies suggest that the agent’s gender does not influence their behavior (Cormier & Woodworth, Citation2008; Logan et al., Citation2006), while others indicate that this can happen in certain situations (Gover et al., Citation2011; Gracia et al., Citation2011; McPhedran et al., Citation2017; Stalans & Finn, Citation2006; Sun, Citation2007). For example, Sun (Citation2007) concluded that there are no differences in the gender variable regarding control actions, but a distinction arises when it comes to support actions.

In turn, Toon and Hart (Citation2005) found that female officers tend to be more likely to advocate that a suspect should be arrested, while men tend to show more impatience with victims and to consider that many victims can easily leave their abusive relationships.

As for Stalans and Finn (Citation2006), they found that female police officers tended to have more stereotypical perspectives about female victims acting more in self-defense and being the only party with injuries and perpetrators acting more intentionally and without justification, but that this did not translate into them being more favorable toward arresting the perpetrator.

The work of Tam and Tang (Citation2005) is very interesting since they compared the perceptions of police officers and social workers and found that male police officers hold the most conservative gender attitudes as well as the most restrictive definitions of psychological wife abuse, female police officers come next and are followed by female social workers. This reveals not only that the police have a more conservative perspective on the issue, but also that men are not necessarily less sensitive to gender issues and IPV. Although this can also be explained by gender-atypical jobs. If this is confirmed, professionals’ gender attitudes and perceptions of wife abuse are influenced more by the type of profession they work than by their gender. Despite this, the gender variable had an influence on the perception that police officers have of the IPV (Gölge et al., Citation2016; Tam & Tang, Citation2005).

Therefore, with the current work, we hope to further the knowledge about the impact that the sex of the law enforcement officer might have on the way they intervene in IPV situations and to learn if that intervention is in some way determined by prejudices related to traditional gender roles within intimate relationships. With this goal, we will use data gathered within a research project on the beliefs, attitudes, and values of the militaries of the National Republican Guard (GNR)—Portuguese law enforcement connected to the arm forces—regarding domestic violence, which strived to study how these views shaped the officers’ performance (Coelho, Citation2019).

That research project was the first work done in Portugal on GNR military personnel and their perceptions about the IPV and has also the particularity of studying a police body that can simultaneously perform both civilian and military police functions. Thus, it focused on a police body that may have a more conservative organizational culture and, consequently, more permeable to patriarchal influence (Ashlock, Citation2019). In most western democratic countries, there is a clear gender inequality in the military services showing the persistence of a men-based organizational culture (Reis & Menezes, Citation2020).

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) and the GNR’s (Portuguese Republican National Guard) Intervention in Portugal

In Portugal, between 2014 and 2019, 316 women were victims of homicide, with 35% of cases occurring within intimate relationships, i.e., 111 women were killed within this context (PJ, Citation2020). In 2018, there were 26,483 police reports of domestic violence, from which 22,423 complaints were classified as IPV (SSI, Citation2019), i.e., 84.67% of all incidents of domestic violence. In this case, 79% of victims were women, 84% of the accused were men and 78% were over 25 years old (SSI, Citation2019). From a global perspective, the total resident population of Portugal was estimated to be 10,295,909 in 2019, data from Statistics Portugal.Footnote1

IPV is the third most reported crime in Portugal. It corresponds to 6.7% of all criminality, second only to theft in motorized vehicles and simple assault (SSI, Citation2019). In 2018, within their policing activity, the GNR received 11,913 reports of domestic violence, which amounts to 45% of all reports of domestic violence in Portugal (Miguel, Citation2018). In 2020, GNR received 47.9% of all IPV reports (13,216), showing that this military police force handles almost half of IPV situations (MAI, Citation2020). The IPV reports are concentrated in the two largest urban regions of the country (Lisboa and Porto, 40%). It is worth mentioning, that the IPV reports to GNR are more spread out in the country (therefore more representative) than those cases reported to the civil police force (MAI, Citation2020). CNN PortugalFootnote2 reported that IPV was the most committed crime in 2020 in Portugal.

As military-like law enforcement, the GNR takes on a series of policing roles, such as patrolling, surveilling, inspecting, and repressing, but in situations of emergency and war it can also carry out military missions as part of a national defense effort. For this reason, it is composed of army personnel organized into a special military body (article 1 of the Organic Law of the GNR—Law no. 63/2007 of 11th November). Their policing duties are performed outside of large urban centers and they have territorial jurisdiction over 94% of the territory and serve 53.8% of the Portuguese population. GNR is organized into 20 territorial commands, 85 territorial detachments, two sub-detachments, and 476 territorial posts (Miguel, Citation2019).

In terms of the characteristics of the GNR’s staff, it comprises 23,022 agents of which 21,125 are men (91.76%) and 1,897 are women (8.24%) (Miguel, Citation2019). Compared to 2017, the rate of feminization increased by 0.19 pp. and the number of female superiors increased by 0.02 pp., meaning that it went up from 0.90 to 0.92% of all officers (Miguel, Citation2019). It is worth mentioning that women were allowed in GNR only after 1994, mainly for administrative work. In 1998, women were finally allowed for military training and after that to enroll in GNR policing services (Videira, Citation2015).

As for age, 42.54% of the staff is either in the 35–39 (4,669) or the 40–44 age groups (5,124) (DPONRH, Citation2019). Finally, concerning seniority, 33.71% of agents have between 15 and 24 years of experience working for the GNR (DPONRH, Citation2019).

Entry into the GNR is secured after the completion of a training course, where the etiology of domestic violence is addressed in a lecture given within the penal law subject, complemented by training on how to communicate and serve victims and prepare the necessary paperwork in domestic violence cases. This initial generic training can be enhanced by continuous specialized training, which until 2018 had only reached 534 agents (2.3% of the entire staff) (SSI, Citation2019).

To further develop its intervention, GNR implemented the IAVE Project (Investigation and Support to Specific Victims), in which the Nuclei of Investigation and Support to Specific Victims (NIAVE) were integrated, which is responsible for dealing with domestic violence crimes, which have a broader scope than the IPV. At the end of 2019, the IAVE had 548 military personnel, 485 men and 63 women, with 100 of these military personnel being part of the NIAVEs (MAI, Citation2020). Essentially, these are the military who have specific training in domestic violence and who are responsible for pursuing the investigations; but when the initial assistance is carried out by other military personnel, it is more likely that they do not have this specific training.

METHODOLOGY

Between 28 November 2017 and 15 January 2018, GNR militaries were questioned about their beliefs, attitudes, and values concerning domestic violence through an online questionnaire. It combined the Scale of Beliefs about Spousal Violence, by Machado et al. (Citation2008), and the Scale of Perceived Severity and Personal Responsibility of Police Officers, by Gracia et al. (Citation2008). It was divided into four sections: the first gathered demographic data and information related to the professional category; the second posed a series of 17 questions (see the first column of for the full list of questions) about beliefs and perceptions concerning domestic violence, using a Likert five-point scale (1—Disagree Completely, 2—Disagree, 3—Neither Agree nor Disagree, 4—Agree, 5—Agree Completely); the third focused on the militaries’ behavior in eight different situations, where they were asked if they would intervene and, if so, with what degree of personal responsibility (on an ordinal scale of 1–5—low to very high responsibility); the fourth and last section presented the same eight situations as in the third section, but inquiries about their perceived level of severity (on an ordinal scale of 0–5-none to very high severity) (Coelho, Citation2019). shows in the first column all eight IPV situations presented in the questionnaire.

Table 1. Second section of the questionnaire about the beliefs and perceptions of male and female GNR militaries regarding domestic violence.

Table 2. Third section of the questionnaire about the GNR militaries’ decision to intervene or not when confronted with different situations, and in case of intervention, with what degree of responsibility.

After formal authorization from the Command of the GNR to conduct the survey, the link to the online questionnaire was sent to the institutional email address of every officer and later sent again, via e-mail, through the proper chain of command. Participation in the questionnaire was voluntary and the answers were anonymous.

The questionnaire was solely aimed at militaries stationed at territorial units capable of responding to domestic violence calls, thus encompassing a total of 16,373 agents. After realizing that the initial participation of some territorial units was minimal, they were asked to divulge again the link to the questionnaire among their staff.

In total, we received 1,872 answers, which corresponds to 11.4% of the target population. One of the questionnaires was rejected due to incoherence in the demographic and professional category questions since it described a situation that would have been impossible in the context of the GNR. Therefore, the sample was reduced to 1,871 valid answers.

The vast majority of the people who answered the questionnaire were male (89.5%), with 47% of them belonging to the 36–45 age group and 32.3% to the 26–35 one. Most of the militaries said that they lived with a partner (71.4%). In terms of educational background, 72.6% have a high-school diploma and only 9% have a college degree. Regarding their rank, most of them are guards (low rank) (81.7%), 16.2% are sergeants and 2.1% are officers (high rank). The years of service of 45.6% of the respondents varies between 11–20 and 26.6% have served <10 years. In terms of their duties, 60.3% do patrol work and 18.3% hold leadership positions.

Statistical analysis includes correlation analysis (Spearman’s Rho), Kappa agreement coefficient, and the Mann–Whitney U or Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to analyze the data distribution differences, as appropriate. A p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The results were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 25.

RESULTS

contains the answers to the second section of the questionnaire, all 17 questions, related to beliefs and perceptions about IPV.

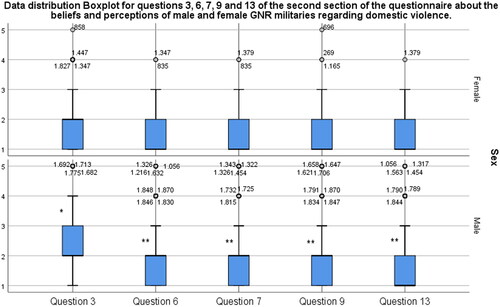

From the data of , we have selected for a more thorough analysis questions 3, 6, 7, 9, and 13, since these were the ones where we have identified greater differences in the answers depending on the respondent’s sex. These differences are significant as shown by the Mann–Whitney U Test: p < 0.001. presents the distributions of the answers to these selected questions, with the median of females’ answers being significantly lower than the median of males’ (Z Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test). The females’ median response was “1—Disagree Completely” in four of the five questions.

Figure 1. Data distribution boxplot for questions 3 (“violence against women only happens when there are other problems in the family …”), 6 (“men only hit women when they have “lost their mind” or when women have done something”), 7 (“if women behaved like good wives they would not be abused”), 9 (“an unfaithful woman deserves to be punished”), and 13 (“intimate partner violence is a private matter…”) of by sex. Kolmogorov–Smirnov Test *p = 0.011, **p < 0.001 (1—disagree completely to 5—agree completely).

Regarding women, the answers to questions 6 (“Men only hit women when they have “lost their mind” or when women have done something”) and 7 (“If women behaved like good wives they would not be abused”) show a strong and significant monotonic positive correlation (Spearman’s rho correlation = 0.638, p < 0.001) and a moderate Kappa agreement coefficient of 0.555 (p < 0.001); the answers to question 9 (“An unfaithful woman deserves to be punished”) and 13 (“Intimate partner violence is a private matter. It should be solved within the household and others should stay out of it”) show a strong and significant monotonic positive correlation (Spearman’s rho correlation = 0.602, p < 0.001) and a moderate Kappa agreement coefficient of 0.487 (p < 0.001).

Regarding men, the answers to questions 6 and 7 show a strong and significant monotonic positive correlation (Spearman’s rho correlation = 0.637, p < 0.001) and a moderate Kappa coefficient of 0.499 (p < 0.001).

As for the other questions (except for question 3—“Violence against women only happens when there are other problems in the family …”), there are significant positive correlations between them (p < 0.001) considering both sexes. Nonetheless, these are moderate (0.5 < R < 0.6) and indicate fair agreement. The answer to question 3 does not have a significant correlation with any other question in either of the sexes.

contains the results of the third and fourth sections of the questionnaire, where we intended to find out if in a given situation of IPV the GNR military would intervene or not, and if they did, what was their perceived degree of responsibility; where 1 was practically not responsible and 5 was completely responsible for doing something (third section of the questionnaire, see ). In the degree of severity, we asked the respondents how they would rate the severity of the different IPV situations on a scale of 0 to 5 if they had witnessed or known about them, where a higher score meant greater perceived severity (fourth section of the questionnaire, see ) and zero presumably corresponded to a situation of nonintervention.

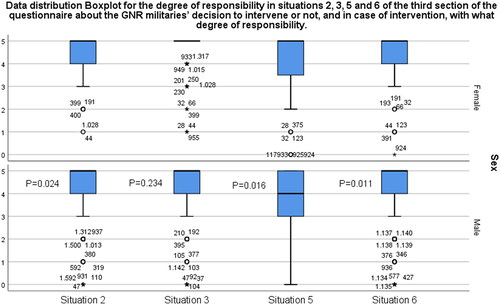

Situations 2, 3, 5, and 6 were chosen for a more in-depth analysis since the number of agents who decided not to intervene is greater. In situation 8, there are also 23 answers of nonintervention, but since it is partly similar to some of the ones that were chosen, we tried to avoid repeating the same type of IPV.

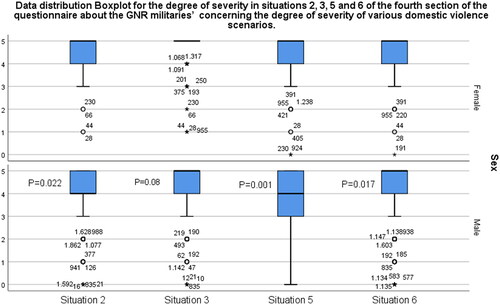

There is a significant difference between sexes in the distribution of the degree of responsibility in three of the four situations that were analyzed. as shown by the Mann–Whitney U Test (). This difference is seen in the same situations regarding the degree of severity (). The disparity between sexes is starker in situation 5 (“During an argument, a man slaps his partner and she hits him back”), with men giving a lower responsibility and severity rating.

Figure 2. Data distribution boxplot for the degree of responsibility in situations 2 (“during an argument a man hits his female partner and apologizes afterwards”), 3 (a woman is repeatedly battered by her partner, which causes small cuts and bruises, but she does not want to report him”), 5 (“during an argument a man slaps his partner and she hits him back”), and 6 (“a woman is constantly belittled and humiliated by her partner”) of by sex. Mann–Whitney U test with statistical significance p < 0.05 (0-does not intervene, 1–5 ordinal scale for the degree of responsibility).

Figure 3. Data distribution boxplot for the degree of severity in situations 2 (“during an argument a man hits his female partner and apologizes afterwards”), 3 (“a woman is repeatedly battered by her partner, which causes small cuts and bruises, but she does not want to report him”), 5 (“during an argument a man slaps his partner and she hits him back”), and 6 (“a woman is constantly belittled and humiliated by her partner”) of by sex. Mann–Whitney U Test with statistical significance p < 0.05 (0–5 ordinal scale for the degree of severity).

Moreover, we analyzed the correlation (Spearman’s rho) and agreement (Kappa coefficient) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity for the same situations, considering the same sex.

Regarding the female group, in situation 2 (“During an argument, a man hits his female partner and apologizes afterward”) there is a strong correlation (R = 0.672, p < 0.001) and a moderate agreement (Kappa coefficient = 0.534, p < 0.001) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity. In situation 3 (“A woman is repeatedly battered by her partner, which causes small cuts and bruises, but she does not want to report him”), there is a strong correlation (R = 0.694, p < 0.001) and a strong agreement (Kappa coefficient = 0.651, p < 0.001) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity. On the other hand, situations 5 (“During an argument, a man slaps his partner and she hits him back”) and 6 (“A woman is constantly belittled and humiliated by her partner”) show a very strong correlation (R = 0.731 and R = 0.780, p < 0.001, respectively) and a moderate agreement (Kappa coefficient = 0.531 and 0.572, p < 0.001, respectively) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity.

In the male group, situations 2 and 3 show a strong correlation (R = 0.695 and R = 0.690, p < 0.001, respectively) and a moderate agreement (Kappa coefficient = 0.502 and 0.578, p < 0.001, respectively) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity. As for situations 5 and 6, they present a very strong correlation (R = 0.763 and R = 0.734, p < 0.001, respectively) and a moderate agreement (Kappa = 0.563 and 0.575, p < 0.001, respectively) between the degree of responsibility and the degree of severity.

In we observe that in seven of the eight situations at least 99.5% of women would intervene, in contrast to men, whose percentage of nonintervention oscillates between 0.8 and 3.3% (14 and 55 agents).

Situation 5 is the only one where four women (2%) answered that they would not intervene, so we decided to check the severity rating they had given to it. We realized that they had rated it differently (0, 2, 3, and 5); consequently, nonintervention did not necessarily correspond to a lower perception of severity, contrary to what we expected. In situation 6, the only woman who would not intervene gave it a severity score of 5, which is the highest.

DISCUSSION

The distribution of the answers by the various points of the scale indicates differences in the way the two sexes assess IPV, even though they generally show that the vast majority of GNR military have an adequate understanding of IPV and that they guide their intervention according to the framework associated with the models of police action. This is corroborated by the study of Brown (Citation2001). Sun (Citation2007) also stated that there are no differences in the gender variables relating to police control, suggesting that they are strongly oriented by police norms and protocols.

In every situation presented, women disagree (completely) with the statements in a higher percentage than men. Of the five analyzed situations, only the situation when violence against women is associated with other problems in the family does not show a positive correlation with the others, perhaps because it points to “external” reasons for IPV, meaning that there is not a direct link to the couple’s relationship. In fact, this is the situation where both sexes disagree the least. Conversely, in all other situations, the justification for violence results in a transference of responsibility onto the female victim, who must have done something to provoke it, or in consigning the problem to the private sphere, implying that the situation and its resolution is solely the couple’s business, which constitutes a practice that unprotects victims and puts them in dangerous situations.

The differences found in the answers depending on the sex of the military also occur in the situations relating to gravity and intervention. The data shows the assignment of a high degree of responsibility in the decision to intervene and in the perceived degree of severity of all presented situations. The research from Gover et al. (Citation2011) and Toon and Hart (Citation2005) also pointed out that the female police officers tend to defend more the arrest of male aggressors.

The results indicate that in every IPV situation, women give the maximum severity score in a higher percentage than men. The same is true of the degree of responsibility to intervene, except where mutual abuse is described, with men assigning a greater responsibility. This is also the situation where a greater number of respondents, both men and women, answered that they would not intervene.

On the other hand, we concluded that the assignment of the maximum degree of responsibility does not coincide with the percentage of the maximum degree of severity. Namely, the degree of responsibility to intervene is higher than the degree of severity perceived in situations 1, 2, and 4 (three situations with actual or possible violence), while the opposite occurs in situations 5 (only by women) and 8 (both situations depict mutual violence)—see . Therefore, the data suggests that the assessment that is made of each of the situations presented in the questionnaire can be affected by the respondents’ beliefs and personal values. These differences are related to gender roles, with women assigning a higher degree of severity probably due to an identification with and empathy for the victims (e.g., situation 5—“During an argument, a man slaps his partner and she hits him back,” ). This is not surprising, since violence against women is disproportionately more represented than violence against men. Which is the result of the long-established conventions that allow men to perpetrate acts of IPV (Lisboa et al., Citation2007, Citation2008; York, Citation2011).

This idea is reinforced by the differences found in the mutual abuse situation (number 5), where men were assigned a greater severity than women—a difference of 6.6 pp. in the sum of scores 4 and 5 (85.2 vs. 78.6%). Nonetheless, regarding the degree of responsibility, the values are practically identical for both genders, though significantly lower than the degree of severity, with 65% of women assigning the score 4 and 5, while the same was observed in 65.8% of men.

Even though situation 8 () also describes a scenario of mutual aggression, in this case, the violence and abuse are recurrent, which might explain why respondents of both sexes assign a higher degree of responsibility and severity to it and why the number of those who say they would not intervene is lower.

We observed that only in two cases is the degree of responsibility to intervene higher than the perceived degree of severity. Specifically in situation 2, where an aggression followed by an apology by the aggressor is described, with men seeming to value the aggressor’s show of regret when assessing the degree of severity (78.7% severity; 79.4% responsibility). And in situation 4, where there is an insult and the threat of violence, with women choosing a higher degree of responsibility compared to severity, which seems to suggest that they value the fact that there was no bodily harm (83.1% severity; 87.8% responsibility).

Therefore, this survey indicates the existence of a relationship between the sex of the military and the beliefs, attitudes, and values espoused by GNR militaries regarding IPV, which in turn determine perceptions about the severity of IPV situations and may condition the militaries’ practical intervention, given that they are endowed with discretion when deciding whether to intervene or not, or how to act in each situation.

The results of this study confirm what has been observed in previous research, which warns against the influence that police officers’ prejudices might have on decisions about how to act and properly respond to IPV situations (Goodman-Delahunty & Crehan, Citation2016; Gracia et al., Citation2008; Rich & Seffrin, Citation2012; Stover et al., Citation2010). In addition, our study identifies the particularity of the situations when the stereotypes of gender roles and the hierarchy of power in male and female relationships play an important role.

Even though the number of women who answered this questionnaire is relatively small, they make up 10.5% of our sample, which is greater than the proportion of female GNR militaries, estimated at around 8.24% (Miguel, Citation2019). In this sense, our sample is representative of the population, and the results are significant. The organizational context of military services like GNR is male-dominated, and even after 20 years women military have difficulties in operational infrastructures (e.g., private facilities may not exist) and there is a lack in the legal framework to promote service equality (Videira, Citation2015).

A limitation of this study may be the possible social desirability bias of this type of questionnaire regarding the questions that can be viewed favorably by others or represent desirable behavior.

CONCLUSIONS

This article helps to further the knowledge about the influence that the sex of the law enforcement officer has on their beliefs and perceptions of IPV and subsequent decision to intervene (or not), from the degrees of severity (attributed to situations of aggression between intimate partners) and responsibility for intervention, showing that there are differences in understanding between female and male officers. Even though most GNR militaries generally act according to the interpretative framework associated with the models of police intervention, we have identified differences in perception and approach based on the military’s sex.

Female militaries tend to show greater disagreement with some stereotypes associated with IPV, to classify them more severely, and to assume a greater degree of responsibility in intervening in IPV situations compared to their male comrades. Associated with the scarce initial training and the reduced number of militaries who have specialized training, this reveals the need for the GNR to implement a training plan based on gender issues and on IPV, to contradict some less correct beliefs and perceptions about the IPV.

Although not being the aim of this research, these data raise once again the question of how to ensure a greater protection for victims (who are mostly women) and if this should be done by teams composed entirely of women or with a mixed composition, in detriment of fully male teams.

In a previous study conducted by Wolf et al. (Citation2003), victims pointed out that one aspect that could improve police response was the hiring of more female police officers. However, in the study carried out by HMIC (Citation2015) victims mentioned the lack of empathy and understanding of policewomen as a negative aspect of the police’s first response. The option for female only teams poses other problems, such as adherence to a perspective that there are jobs that can be better performed by women (Chan & Ho, Citation2017; Santos, Citation2004). The solution pointed out by Carrington et al. (Citation2022) is that women-led police stations encourage earlier reporting, widen access to justice and help to prevent further re-victimization, especially in the global south. Police stations that offer a multi-disciplinary integrated response, also enhance trust in police and improve victim satisfaction with police responses (Carrington et al., Citation2022).

The organizational culture of GNR and underlined social principles, believe that women military are not suitable for high violence situations but at the same time may be more suitable for research and situations of IPV (Videira, Citation2015). This makes it difficult for women to integrate normal police work and justifies or reinforces a patriarchal culture in police forces (Chan & Ho, Citation2017; Garcia, Citation2021; Santos, Citation2004).

The results of the present work, also show how important it is to consider the assessment that men make of IPV since they tend to justify the aggression by focusing on the victim’s responsibility, i.e., they transfer the reason for the episode of violence to the women or locate the problem in the private sphere, thus suggesting that the situation and its resolution is exclusively the couple’s business. Therefore, one can suspect that there are cases of IPV against women that are overlooked or disregarded by the police force since the great majority of police officers are men (and even more in military-based law enforcement). This article is unique since there are no other works from a military police force perspective (to our knowledge).

This data was collected before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the UN 2020 Policy BriefFootnote3 shows that IPV increased during the pandemic. The impacts of COVID-19 are exacerbated for women and girls simply by virtue of their sex since they were confined by their aggressors. These long periods where the victims were closer to the aggressor and with less liberty to ask for help show that special attention is needed by police officers to detect and intervene.

This paper is an important step to draw the attention of the political agenda in relation to the training of the military and shows that more can be done at the research level, focusing on the questions of the influence of the sex of the police officer in the intervention in IPV situations.

Bearing in mind the magnitude and impact that this issue still has on contemporary societies, we advocate that the police adapt and develop their training and intervention models based on the knowledge acquired about victims and aggressors (also during the COVID-19 pandemic). In traditional man professions, there is a need for greater parity between men and women, with a higher inclusion of women especially in the police and military forces.

The organizational culture of police forces needs to change to allow for gender-balanced teams and women in leading posts. So that police stations can be more victim-centered with a set of multidisciplinary support systems and emphatic responses to all IPV situations.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All analyzed data is presented in the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

REFERENCES

- Apsler, R., Cummins, M. R., & Carl, S. (2003). Perceptions of the police by female victims of domestic partner violence. Violence against Women, 9(11), 1318–1335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203255554

- Ashlock, J. M. (2019). Gender attitudes of police officers: Selection and socialization mechanisms in the life course. Social Science Research, 79, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.12.008

- Basile, K. C., & Black, M. C. (2011). Intimate partner violence against women. In C. Renzetti (Ed.), Sourcebook on violence against women (pp. 111–131). Sage Publications.

- Birdsall, N., Kirby, S., & McManus, M. (2017). Police–victim engagement in building a victim empowerment approach to intimate partner violence cases. Police Practice and Research, 18(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2016.1230061

- Birdsey, E., & Snowball, L. (2013). Reporting violence to police: A survey of victims attending domestic violence services. Crime and Justice Statistics – Bureau Brief, 91. NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research.

- Brown, A. W. (2001). Obstacles to women accessing forensic medical exams in cases of sexual violence. Unpublished background paper to the Consultation on the Health Sector Response to Sexual Violence, WHO Headquarters, Departments of Injuries and Violence Prevention and Gender and Women’s Health. Retrieved from www.hrw.org/backgrounder/wrd/who-bck.pdf

- Breiding, M. J., Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Black, M. C., Mahendra, R. R. (2015). Intimate partner violence surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Version 2.0. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv/intimatepartnerviolence.pdf

- Buzawa, E., Hotaling, G., & Klein, A. (1998). What happens when a reform works? The need to study unanticipated consequences of mandatory processing of domestic violence. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 13(2), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02806712

- Buzawa, E., Hotaling, G., Klein, A., Byrne, J. (2000). Response to domestic violence in a pro-active court setting – Final report. Retrieved from https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/181427.pdf

- Carrington, K., Rodgers, J., Sozzo, M., & Puyol, M. V. (2022). Re-theorizing the progress of women in policing: An alternative perspective from the Global South. Theoretical Criminology, 136248062210996. https://doi.org/10.1177/13624806221099631

- Chan, A. H., & Ho, L. K. (2017). Women in the Hong Kong Police Force Organizational Culture, Gender and Colonial Policing. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Coelho, R. P. P. S. (2019). [Violência doméstica e de género: Crenças, atitudes e valores dos militares da GNR] [MSc dissertation in Intercultural Relations]. Universidade Aberta.

- Cormier, N. S., & Woodworth, M. T. (2008). Do you see what I see? The influence of gender stereotypes on student and Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) perceptions of violent same-sex and opposite-sex relationships. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 17(4), 478–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926770802463446

- Day, A. S., Jenner, A., & Weir, R. (2018). Domestic abuse: Predicting, assessing and responding to risk in the criminal justice system and beyond. In E. Milne (Ed.), Women and the criminal justice system: Failing victims and offenders (pp. 67–94). Palgrave Macmillan.

- DeKeseredy, W. S. (2011). Violence against women: Myths, facts, controversies. University of Toronto Press.

- Dobash, R. E., Dobash, R. P., Cavanagh, K., & Medina-Ariza, J. (2007). Lethal and non-lethal violence against an intimate female partner: Comparing male murderers with non-lethal abusers. Violence against Women, 13(4), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207299204

- Dobash, R. P., & Dobash, R. E. (2003). Violence in intimate relationships. In W. Heitmeyer & J. Hagan (Eds.), International handbook of violence research (pp. 737–752).Kluwer.

- Dowling, C., Morgan, A., Boyd, C., & Voce, I. (2018). Policing domestic violence: A review of the evidence. Research Report 13. Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Divisão de Planeamento, Obtenção e Nomeação de Recursos Humanos. (2019). Balanço Social 2018 – Relatório. Divisão de Planeamento, Obtenção e Nomeação de Recursos Humanos. GNR.

- European Institute for Gender Equality. (2020). Gender statistics database. Intimate partner violence indicators. EIGE’s Publications. Retrieved from https://eige.europa.eu/publications

- Eigenberg, H. M., Kappeler, V. E., & McGuffee, K. (2012). Confronting the complexities of domestic violence: A social prescription for rethinking police training. Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations, 12(2), 122–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332586.2012.717045

- Enguix, B. (2020). Gender, sexuality and affects: Current becomings. In B. Enguix & C. P. Vieira (Eds.), Sexualities, gender and violence: A view from the Iberian Peninsula (pp. 113–128).Nova Science Publishers.

- Erez, E. (2002). Domestic violence and the criminal justice system: An overview. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 7(1), p. 4. Retrieved from https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Volume72002/No1Jan2002/DomesticViolenceandCriminalJustice.html

- Fedina, L., Backes, B. L., Jun, H.-J., DeVylder, J., & Barth, R. P. (2019). Police legitimacy, trustworthiness, and associations with intimate partner violence. Policing: An International Journal, 42(5), 901–916. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-04-2019-0046

- FRA - European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. (2014). Violence against women: An EU-wide survey – Main results. Retrieved from https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2014-vaw-survey-main-results-apr14_en.pdf

- Garcia, V. (2021). Women in policing around the world doing gender and policing in a gendered organization. Routledge.

- Gölge, Z. B., Sanal, Y., Yavuz, S., & Arslanoglu-Çetin, E. (2016). Attitudes toward wife abuse of police officers and judiciary members in Turkey: Profession, gender, ambivalent sexism and sex roles. Journal of Family Violence, 31(6), 785–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9823-1

- Goodman-Delahunty, J., & Crehan, A. C. (2016). Enhancing police responses to domestic violence incidents: Reports from client advocates in New South Wales. Violence against Women, 22(8), 1007–1026. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801215613854

- Gordon, M. (2000). Definitional issues in violence against women: Surveillance and research from a violence research perspective. Violence against Women, 6(7), 747–783. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801200006007004

- Gover, A. R., Paul, D. P., & Dodge, M. (2011). Law enforcement officers’ attitudes about domestic violence. Violence against Women, 17(5), 619–636. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211407477

- Gracia, E., Gracía, F., & Lila, M. (2011). Police attitudes toward policing partner violence against women: Do they correspond to different psychosocial profiles? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(1), 189–207.

- Gracia, E., García, F., & Lila, M. (2008). Police involvement in cases of intimate partner violence against women: The influence of perceived severity and personal responsibility. Violence against Women, 14(6), 697–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208317288

- Hanganu, B., Crauciuc, D., Petre Ciudin, V., Velnic, A., Manoilescu, I., & Ioan, B. G. (2017). Domestic violence in the postmodern society: Ethical and forensic aspects. Postmodern Openings, 8(3), 46–58. https://doi.org/10.18662/po/2017.0803.05

- Harway, M., Geffner, R., Ivey, D., Koss, M., Murphy, B., Mio, J., & O’Neil, J. (2002). Intimate partner abuse and relationship violence. American Psychological Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/about/division/activities/partner-abuse.pdf

- Harne, L., & Raford, J. (2008). Tackling domestic violence – Theories, policies and practice. Open University Press.

- HMIC. (2015). Increasingly everyone’s business: A progress report on the police response to domestic abuse. HMIC.

- Holder, R. (2001). Domestic and family violence: Criminal justice interventions. Issues Paper 3. Australian Domestic & Family Violence Clearinghouse.

- Johnson, H., Ollus, N., & Nevala, S. (2008). Violence against women – An international perspective. Springer.

- Li, L., Sun, Y. I., Lin, K., & Wang, X. (2021). Tolerance for domestic violence: Do legislation and organizational support affect police view on family violence? Police Practice and Research, 22(4), 1376–1389. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2020.1866570

- Lisboa, M., Barros, P. P., & Cerejo, S. D. (2008). Custos Sociais e Económicos da Violência Exercida Contra as Mulheres em Portugal: dinâmicas e processos socioculturais. In Atas do VI Congresso Português de Sociologia. Associação Portuguesa de Sociologia.

- Lisboa, M., Barros, P. P., Cerejo, S. D., & Barrenho, E. (2007). Custos Económicos da prestação de cuidados de saúde às vítimas de violência. Comissão para a Igualdade e para os Direitos das Mulheres.

- Lisboa, M., Carmo, I., Vicente, L. B., Nóvoa, A., Barros, P. P., Roque, A., Silva, S. M., Franco, L., & Amândio, S. (2006). Prevenir ou Remediar. Os custos sociais e económicos da violência contra as mulheres. Edições Colibri.

- Lockwood, D., & Proshaka, A. (2015). Police officer gender and attitudes toward intimate partner violence: How policy can eliminate stereotypes. International Journal of Criminal Justice Sciences, 10(1), 77–90.

- Logan, T. K., Shannon, L., & Walker, R. (2006). Police attitudes toward domestic violence offenders. Violence against Women, 21(10), 1365–1374.

- Machado, C., Matos, M., & Gonçalves, M. (2008). Manual da Escala de Crenças sobre a Violência Conjugal (E.C.V.C.) e do Inventário de Violência Conjugal (I.V.C.). Editora Psiquilibrios Edições.

- Ministério da Administração Interna. (2020). Violência Doméstica – Relatório anual de monitorização 2019 and 2020. Ministério da Administração Interna. https://www.sg.mai.gov.pt/Paginas/ViolenciaDomesticaRelatorios.aspx

- McMullan, E. C., Carlan, P. E., & Nored, L. S. (2010). Future law enforcement officers and social workers: Perceptions of domestic violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 25(8), 1367–1387. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260509346062

- McPhedran, S., Gover, A. R., & Mazerolle, P. (2017). A cross-national comparison of police attitudes about domestic violence: A focus on gender. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 40(2), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-06-2016-0083

- Menjívar, C., & Salcido, O. (2002). Immigrant women and domestic violence: Common experiences in different countries. Gender & Society, 16(6), 898–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124302237894

- Miguel, L. F. B. (2019). Plano de Atividades 2019. GNR.

- Miguel, L. F. B. (2018). Relatório de Atividades 2018. GNR.

- Muftić, L., & Cruze, J. R. (2014). The laws have changed, but what about the police? Policing domestic violence in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Violence against Women, 20(6), 695–715. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214540539

- Myhill, A., & Johnson, K. (2016). Police use of discretion in response to domestic violence. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 16(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895815590202

- OMA-UMAR. (2020). Dados Preliminares sobre as Mulheres Assassinadas em Portugal: Dados 1 janeiro a 15 de novembro de 2020. UMAR – União de Mulheres Alternativa e Resposta. Retrieved from www.umarfeminismos.org/

- Pérez-Martínez, V., Sanz-Barbero, B., Ferrer-Cascales, R., Bowes, N., Ayala, A., Sánchez-SanSegundo, M., Albaladejo-Blázquez, N., Rosati, N., Neves, S., Vieira, C. P., Jankowiak, B., Waszynska, K., & Vives-Cases, C. (2021). The role of social support in machismo and acceptance of violence among adolescents in Europe. Lights4Violence baseline results. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(5), 922–929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.09.007

- Polícia Judiciária. (2020). Homicídios nas relações de intimidade – Estudo dos Inquéritos investigados pela Polícia Judiciária (2014 a 2019). Polícia Judiciária.

- Poteyeva, M., & Sun, I. Y. (2009). Gender differences in police officers’ attitudes: Assessing current empirical evidence. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(5), 512–522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.07.011

- Ragusa, A. T. (2012). Rural Australian women’s legal help seeking for intimate partner violence: Women intimate partner violence survivors’ perceptions of criminal justice support services. Violence against Women, 28(4), 685–717.

- Reis, J., & Menezes, S. (2020). Gender inequalities in the military service: A systematic literature review. Sexuality & Culture, 24(3), 1004–1018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-019-09662-y

- Rich, K., & Seffrin, P. (2012). Police interviews of sexual assault reporters: Do attitudes matter? Violence and Victims, 27(2), 263–279.

- Russell, B. (2017). Police perceptions in intimate partner violence cases: The influence of gender and sexual orientation. Journal of Criminal Violence, 41(2), 193–205.

- Sani, A., Coelho, A., & Manita, C. (2018). Intervenção em situações de violência doméstica: Atitudes e crenças de polícias. Psychology, Community & Health, 7(1), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.5964/pch.v7i1.247

- Santos, C. M. (2004). En-gendering the Police: Women’s police stations and feminism in São Paulo. Latin American Research Review, 39(3), 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.2004.0059

- Santos, L. (2020). Men behind the mask: The epistemology of difference. In B. Enguix & C. P. Vieira (Eds.), Sexualities, gender and violence: A view from the Iberian Peninsula (pp. 113–128). Nova Science Publishers.

- Sistema de Segurança Interna. (2019). Relatório Anual de Segurança Interna – Ano 2018.

- Stalans, L. J., & Finn, M. A. (2006). Public’s and police officers’ interpretation and handling of domestic violence cases – Divergent realities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(9), 1129–1155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260506290420

- Stover, C. S., Berkman, M., Desai, R., & Marans, S. (2010). The efficacy of a police-advocacy intervention for victims of domestic violence: 12 Month follow-up data. Violence against Women, 16(4), 410–425. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801210364046

- Sun, I. Y. (2007). Policing domestic violence: Does officer gender matter? Journal of Criminal Justice, 35(6), 581–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2007.09.004

- Tam, S. Y., & Tang, C. S. (2005). Comparing wife abuse perceptions between Chinese police officers and social workers. Journal of Family Violence, 20(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-005-1507-1

- Toon, R., & Hart, B. (2005). Layers of meaning: Domestic violence and law enforcement attitudes in Arizona. Morisson Institute for Public Policy.

- Torres, A., Pinto, P., Costa, D., Coelho, B., Maciel, D., Reigadinha, T., & Theodoro, E. (2018). (ed.) Igualdade de Género ao Longo da Vida: Portugal no Contexto Europeu. Fundação Francisco Manuel dos Santos. Retrieved from https://www.ffms.pt/FileDownload/97de6517-2059-46b4967af3b8a15ef139/igualdadede-genero-e-idades-da-vida

- Trujillo, M. P. (2008). Police response to domestic violence: Making decisions about risk and risk management. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 23(4), 454–473.

- Videira, C. S. C. (2015). A influência do género no exercício de funções na Guarda Nacional Republicana. Academia Militar. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.26/12057

- Vieira, C. P. (2020). Portuguese youth’s discourses on masculinity: Broken silences. In B. Enguix & C.P. Vieira (ed.), Sexualities, gender and violence: A view from the Iberian Peninsula (pp. 113–128). Nova Science Publishers.

- Vieira, C. P. (2017). Sexualidade e Género: Educar para um Social Plural. In S. Neves & D. Costa (Eds.), Violência de Género (pp. 317–337).Edições CIEG.

- Vigurs, C., Wire, J., Myhill, A., & Gough, D. (2016). Police initial responses to domestic abuse – A systematic review. College of Policing.

- Wang, L. (2016). Factors influencing attitude toward intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 29, 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.06.005

- Wolf, M. E., Ly, U., Hobart, M. A., & Kernic, M. A. (2003). Barriers to seeking police help for intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 121–129.

- York, M. R. (2011). Gender attitudes and violence against women. LFB Scholarly Publishing.