ABSTRACT

The entrepreneurial learning literature remains underdeveloped and lacks a clear understanding of the learning process. Building on an in-depth case study of four Scandinavian gourmet restauranteurs, we argue that learning to act on entrepreneurial tasks involves opening-up and focusing processes. We propose a process model that specifies how changing perceptions of complexity and self-efficacy influence an individual’s preference for experimentation (opening up) and modelling (focusing) when acquiring new experience. Specifically, in situations perceived as complex, individuals will likely opt for modelling; however, individuals who feel highly self-efficacious will likely rely more on experimentation.

Introduction

Similar to craftsmen, it seems that entrepreneurs largely learn on the job. The skills relevant to the successful creation, management, and operation of a business seem largely experiential in nature (Morris et al. Citation2012; Politis Citation2005). Entrepreneurs learn from their own experience (Cope Citation2011; Toft-Kehler, Wennberg, and Kim Citation2014; Ucbasaran, Wright, and Westhead Citation2003) and from the example of others (Bosma et al. Citation2012; Nanda and Sørensen Citation2010; Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017).

To date, research on entrepreneurial learning has focused on theorizing about learning prior to market entry and when learning from experience is better than learning from others (Choi, Lévesque, and Shepherd Citation2008; Lévesque, Minniti, and Shepherd Citation2009). However, although there is growing agreement that entrepreneurial learning is a situated social process, it has been approached as an atomistic approach, largely disregarding the influence of context (Toutain et al. Citation2017). In contrast, our paper contextualizes entrepreneurial learning. We explore learning in a natural setting – by investigating how individuals interact with their context and how they learn in the process – to develop a situated process model of entrepreneurial learning and how it unfolds over time. Examining learning over time is important in entrepreneurship because of complexity, and uncertainty. It is virtually impossible for entrepreneurs to be fully prepared for new unknowable situations. Further, because the entrepreneurial tasks change over time as the venture develops, there are limits to the usefulness of prior experience (Muehlfeld, Rao Sahib, and Van Witteloostuijn Citation2012). Therefore, we propose that self-efficacy beliefs may be as relevant for entrepreneurs’ engagement in entrepreneurial behaviour (Newman et al. Citation2018) as learning and performance (Engel et al. Citation2014; Krueger Citation2007; Miao, Qian, and Ma Citation2017).

Conceptually, we draw on social learning theory (Bandura Citation1977b). Due to uncertainty entrepreneurs may doubt that their capabilities are sufficient to complete the tasks required to achieve their desired entrepreneurial outcome. This uncertainty makes belief in one’s ability to achieve the focal goal salient (Engel et al. Citation2014; Krueger Citation2007). As many entrepreneurs have scant resources and lack the finance required to acquire the needed resources, they typically rely heavily on their social networks when creating a business and learning (Korsgaard, Ferguson, and Gaddefors Citation2015). Self-efficacy and learning from social networks are central in social learning theory, which makes this theory an appropriate foundation for an entrepreneurial learning process model.

This study makes two main contributions to the literature. First, we develop a model of experiential entrepreneurial learning to explain how individuals’ self-efficacy and perceptions of complexity influence their choice of learning mode over time. Specifically, we identify two overlapping processes – focusing and opening up. Focusing is related to learning from others in a context of increasing complexity, where learning refers to identifying the solution to a problem and implementing it. Opening up is related to exploratory learning mainly through experimentation, the implementation of which is based on perceptions of self-efficacy. The present study responds to calls for more research on learning in the context of opportunity exploration and exploitation (Wang and Chugh Citation2014). Second, we show how preferences for learning from experimentation and from modelling change. Extant research has acknowledged the existence of participative (experiential) and observational (i.e., learning from others) learning (Choi, Lévesque, and Shepherd Citation2008; Lévesque, Minniti, and Shepherd Citation2009) and has implicitly assumed that they are stable over time regardless of the task or accumulated knowledge. We show that this assumption is an oversimplification. Our research reveals the contextual conditions under which learning modes (experimentation and modelling), that once seemed appropriate and useful, become less effective and consequently change. We highlight the relevance of cognitive judgements about personal and contextual elements for explaining individuals’ learning mode and subsequent entrepreneurial action. In particular, we show that the perception of a low level of complexity predisposes an individual to experimentation (opening up for new experiences), while modelling is used to implement successful solutions and behaviours (focusing on known solutions). This finding adds to work on the contextualized view of learning (Toutain et al. Citation2017). Our proposed model provides insights into why learning may not always be effective or result in new solutions. We develop our model on the basis of in-depth case studies of fine-dining restauranteurs and their businesses, which proves to be an ideal context to study experiential learning.

The next section presents the conceptual background and a review of the literatures on entrepreneurial learning and general learning. Next, we discuss the empirical context (i.e., gourmet restauranteurs), provide a description of the method used, and a presentation of the findings. We also propose our theoretical model. Finally, we discuss some implications of our study for entrepreneurial learning theory.

Conceptual background

The experiential learning process

Prior research has emphasized the importance of experience and the process of transforming experience into useful knowledge when developing entrepreneurial opportunities (Corbett Citation2005; Pittaway and Thorpe Citation2012; Politis Citation2005). The notion that entrepreneurs transform ideas into new offerings assumes they have agency and are able to identify new applications for their knowledge. The uncertainty and complexity inherent in entrepreneurship mean that entrepreneurs cannot be certain that they possess the knowledge and capabilities needed to complete the tasks required to reach their goals. Therefore, entrepreneurs’ behaviour and willingness to act will be guided in part by their belief in their ability to achieve their goals rather than the actual knowledge they possess (Krueger Citation2007; Newman et al. Citation2018). This view of entrepreneurial learning is closely related to aspects of social learning theory.

Social learning theory considers an individual an agent driven by intentions and forethought who, through the mechanism of self-efficacy, is able to monitor his or her own behaviour, its determinants, and its effects (Bandura Citation2001). Self-efficacy is multidimensional and ‘includes beliefs about capabilities of achieving desired outcomes as well as beliefs about one’s capabilities to complete tasks’ (Drnovsek et al., Citation2010: 335). Simply put, self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to engage successfully in the behaviours needed to achieve certain goals and is shaped by both the individual’s own prior experience and the social example of others. Self-efficacy facilitates openness to and learning from new experiences regardless of their being experienced directly or indirectly (Bandura Citation1977a, Citation1997). As elaborated on below, Bandura’s social learning theory – with its focus on self-regulation, beliefs in one’s own ability, and the experimental and modelling modes of learning – is well suited to exploring entrepreneurial learning.

Moreover, by acting in a social space, entrepreneurs not only rely on the example of other individuals to facilitate their learning but also need to comply with the social norms in their environment in order to be considered legitimate economic actors (Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015; Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017). This reliance on social norms and the availability of a social example help entrepreneurs reduce the perceived uncertainty of the situation by enabling them to copy others’ successful behaviours and avoid unsuccessful behaviours (Baum, Li, and Usher Citation2000; Holcomb et al. Citation2009). Thus, the process of learning from experience is reciprocal and is influenced by behavioural, cognitive, and environmental factors (Bandura Citation1977b; Jack and Anderson Citation2002). Behavioural factors include practice and skills; cognitive factors relate to beliefs, expectations and knowledge; and environmental factors encompass social norms, access to communities, and the influence of others. The reciprocal relationships between an individual and his or her environment makes this model appropriate for the entrepreneurship context. Entrepreneurs deal with uncertainty in part by shaping the environment and their own destinies (Hjorth Citation2004; McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014). Thus, entrepreneurial learning is not only dependent on personal experience; it is also influenced by environmental (i.e., social) and psychological factors (Krueger Citation2007; Toutain et al. Citation2017).

Self-efficacy and learning modes

Without believing in his or her own ability to achieve an intended outcome, an individual is unlikely to engage in intentional actions aimed at reaching that uncertain outcome (Bandura Citation1997; Newman et al. Citation2018). Similarly, without believing in one’s ability to influence one’s surroundings, it is difficult for an individual to acquire new skills and knowledge (Bandura Citation2001; Dempsey and Jennings Citation2014; McGee, Shinnar, Hsu, and Powell Citation2014). The ability to adapt one’s behaviour to be consistent with a new world view (i.e., perceptions about what society desires and expects that emerge from the realization of the availability of new knowledge and new value) requires the development of or changes to self-efficacy beliefs (Engel et al. Citation2014). These beliefs are developed through experimentation, observation of others, and social persuasion (Bandura Citation1977a; Dalborg and Wincent Citation2015). Thus, understanding how individuals learn to deal with uncertainty when engaging in new economic activity requires an understanding of how they adapt their behaviours to changing perceptions of efficacy.

By gaining experience practicing certain tasks or behaviours, entrepreneurs develop new skills and gain new insights. In particular, they are likely to develop the ability to deal with uncertainty and thus the learning needed to be entrepreneur (Engel et al. Citation2014; McMullen and Shepherd Citation2006; Morris et al. Citation2012). While practice influences how individuals see the world and what they deem worthy of pursuing (Erikson Citation2003; Zhao, Seibert, and Hills Citation2005), their personal beliefs and their social environment shape the way they transform acquired experience into knowledge (Bandura, Citation1977b). The most common ways to gain experience are to engage in experimenting or to imitate (model) others’ behaviour (Bandura Citation1977b; Holcomb et al. Citation2009). While mastering a skill (or experimentation) tends to involve a process of trial and error, in the case of modelling, individuals tend to learn by informally observing and then adopting social behaviour – that is, they learn by example rather than by direct experience (Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017). Thus, individuals develop a preference for either mastery or modelling to learn new knowledge and skills, and these preferences reflect their willingness and ability (or lack thereof) to deal with uncertainty (Lévesque, Minniti, and Shepherd Citation2009).

The above discussion suggests that understanding how entrepreneurs learn requires an analysis of their personal beliefs, preferred learning modes (i.e., mastery and/or modelling), and embeddedness in social networks. McMullen and Shepherd (Citation2006) argue that whether an individual engages in entrepreneurial action depends on the desirability and feasibility of his or her particular idea and thus on the individual’s beliefs about his or her own competence, expected acceptance in the market, and support and encouragement from his or her social network. However, little is known about how self-efficacy and perception of complexity interact or about how they influence individuals’ choice of learning mode over time. We explore these aspects below.

Empirical context

Our empirical context is rural Scandinavian gourmet restauranteurs. Gourmet restauranteurs are a recent phenomenon in Scandinavia. Historically, gourmet chefs did not own the restaurants they worked in. However, owning a restaurant is now seen by many chefs as allowing autonomy and creative freedom (Strandgaard Pedersen et al. Citation2006) and providing a rewarding career (Markowska Citation2018). Gourmet restauranteurs own their restaurants and are, by definition, entrepreneurial, creative, and innovative. They introduce new dishes, new ways of cooking, new ingredients, and new ways of presenting and combining meals. Restaurant innovations go beyond menu modifications and food presentation and can include classic product and process innovation behaviours. In particular, restauranteurs often develop and refine cooking techniques and cooking equipment as well as apply technologies adopted by other parts of the restaurant domain. Thus, the nature of the gourmet restaurant business, with its constant innovations driven by restauranteurs, clearly places these restauranteurs in the category of entrepreneur in the classic Schumpeterian sense (Schumpeter Citation1934).

Becoming a restaurant owner requires new skills, particularly entrepreneurial skills. More specifically, because being an accomplished chef does not automatically translate into becoming a successful entrepreneur, these chefs need to learn to combine different logics: those of professional chef and business owner (Markowska Citation2018). Specifically, the restauranteur role requires an individual to be able to relate to his or her environment. It requires the ability to cooperate with suppliers to generate new ideas, products, and services and to transform foodstuffs and other environmental cues into something desirable to create value for customers. Many restauranteurs, especially those in rural contexts, create sophisticated narratives that tell stories of exciting locations, unusual restaurants, and amazing food, using the association between restaurant and location as a way of branding their restaurants. This entrepreneurial storytelling creates desirable conditions for entrepreneurial action but also requires entrepreneurs to become part of the context (Markowska and Lopez-Vega Citation2018). In addition to spatial relationships, professional networks are important in the gourmet restaurant sector as they shape industry norms and expectations and develop cognitive proximity among chefs. Finally, because the restaurants we study are rural and geographically dispersed, local specialization is important. The restaurants are heterogeneous in their concepts, and there is less isomorphic pressure than has been observed in studies of French Michelin star restaurants, for example (Rao, Monin, and Durand Citation2005). These characteristics allowed us to observe the situatedness of the social cognitive processes in which we are interested.

Method

Research design

To respond to the call for more qualitative longitudinal research on entrepreneurial learning (Wang and Chugh Citation2014), we designed a longitudinal study to address our research question. We identified four cases of rural gourmet restauranteurs with varying levels of professional and local embeddedness to analyse how these entrepreneurs learned to pursue an entrepreneurial opportunity in rural Scandinavia. This qualitative multiple case study strategy allowed us to treat the context as part of the phenomenon of interest and enabled us to observe the situatedness of the restauranteurs’ learning (Anderson Citation2000; Pittaway and Thorpe Citation2012; Toutain et al. Citation2017; Zahra, Wright, and Abdelgawad Citation2014). We chose this design to capture how the restauranteurs’ learning process evolved over time and to capture both retrospective and real-time conditions that caused variations to the process (Holcomb et al. Citation2009). This approach has been employed to examine learning processes in prior work (e.g., Taylor and Thorpe Citation2004; Zhang and Hamilton Citation2009; Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017), which makes it possible to build theory derived from data but juxtaposed extant literature (Shepherd and Sutcliffe Citation2011). Finally, this approach allowed us to treat each case as a distinct analytical unit while also considering them as multiple experiments (Eisenhardt and Graebner Citation2007).

Sampling

To select our cases, we adopted a purposive sampling strategy. The four entrepreneurs are Scandinavian males working in restaurants located in rural Scandinavian locations who own and run these restaurants with spouses/business partners. The four cases are similar in many respects (e.g., industry, type of business, location, etc.) but vary in the restauranteurs’ experience and length of time running their restaurants. presents the characteristics of the restauranteurs and their restaurants (names have been altered to protect respondents’ identities).

Table 1. Description of Respondents and Their Restaurants

Data collection

We used both primary and secondary data. Primary data are from 42 interviews (14 with the case restauranteurs and 28 with members of their professional networks) and are supported by more than 180 pages of secondary information (e.g., financial data, information from their websites, media articles, etc.). The main semi-structured interviews were conducted face to face between November 2007 and March 2009 with telephone follow-up interviews conducted in mid-2011. The interviews lasted between 60 and 120 minutes and were digitally recorded (a total of 2,641 interview minutes) and transcribed verbatim. In their first interviews, the entrepreneurs were invited to tell their stories about themselves and their restaurants. This part of the interview was clearly retrospective in nature, but as the interviews progressed during 2007 and 2009, the entrepreneurs were asked to talk more about their current situation, intentions, and future goals. They were asked to report any changes to their businesses and their visions. As the researchers and respondents established trust, the entrepreneurs went into more detail about their plans and reasons for certain decisions.

We mapped the entrepreneurs’ relationships, and in some cases, we interviewed some of the respondents’ social ties, especially suppliers and partners. These multiple sources of evidence allowed us to cross-check the data and increased consistency and reliability.

Data analysis

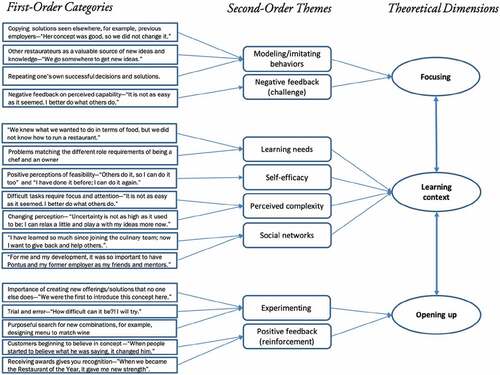

We began the analysis by compiling a story for each restauranteur based on the data collected (Jack Citation2005), which gave a better understanding of each individual case. We coded the data using both a priori codes (e.g., the literature has distinguished between mastery and modelling as learning modes) and free codes that emerged from the data – for example, ‘learning from other chefs’ and ‘learning from suppliers’ as well as ‘focusing’ (i.e., searching for a solution) and ‘opening up’ (i.e., introducing experimentation). This approach allowed us to identify emerging themes and patterns in each case (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). depicts the translation of first-order categories into second-order themes and the associated theoretical dimensions.

Subsequently, we used pattern matching and comparative techniques to interpret the emerging relationships among the different concepts and then compared these patterns across the four cases. For example, cross-case comparison showed that the emerging pattern of concept development and learning from professional networks is influenced by entrepreneurs’ perceptions and feelings of embeddedness in these networks such that the more deeply embedded the entrepreneur, the more he or she uses the networks and the more he or she learns about the concept. Additionally, we used excerpts from the interviews as further evidence (Wolcott, Citation1990) and created tables presenting comparative information for the cases to make the context clearer and to increase the credibility of our analysis (Marshall and Rossman Citation1995).

Findings

We found that entrepreneurship and learning are intertwined, as shown by the entrepreneurs’ use of different learning modes, the influencing contextual variables, and the entrepreneurs’ timing of and reasons for different learning modes.

Entrepreneurship and learning

Although all our entrepreneurs had been successful in the past and two (Charlie and Jonathan) had previous entrepreneurial experience, all realized they needed to learn new things as they engaged in their entrepreneurial endeavours. For example, Allan said that when he decided to strike out on his own, he was naïve. He did not think it would be so much different from being a chef but soon realized that becoming an entrepreneur was more complicated. He said,

I made the food, cleaned, did the books. I started to think differently there. The first thing was I met the customers. I had been a chef before but had not met my customers. I was there cooking in the kitchen; if somebody was not satisfied with the food, it did not affect me … . And when they [the customers] said this is not good, I started to think maybe they know what they are saying. You had to learn, what works what does not.

Also, Allan’s decision to purchase a restaurant had not gone as planned:

This restaurant had a location; it had tables and chairs. I was not focused [when making this decision] because we thought we were getting it cheap and basically would have a restaurant. So, we bought it but because we had no money to start with. We continued to serve the food on the Chinese restaurant plates for 18 months. We could not afford to buy new plates.

Allan reflected that these sorts of problems made him realize the complexity of his entrepreneurial tasks and the inherent need to learn.

Similarly, when Fredrik and his spouse started their restaurant, they knew exactly what food they wanted to sell and what the overall concept should be but did not know how to run the business operationally, so they had to learn quickly. Fredrik noted, ‘We were pretty sure what we wanted to do. We had been planning for years what food to serve, but the restaurant – we did not know anything about it. We had to learn the everyday business by doing.’ Fredrik also explained,

There is a difference when you work for someone else and when you run your own business. Before, I only had to focus on ordering the ingredients needed and producing new exciting dishes; the economic cost and the price the customer paid did not matter to me. Here, you realize really quickly the challenge involved in setting the right price and the consequences of not doing it well. I am still learning how to do it.

These skills were not a major concern in his previous employment, but when he became an entrepreneur, they became essential for ensuring that his business survived. Fredrik realized that opening the restaurant was only the first step and that learning how to operate it was necessary if he wanted to make it successful.

After deciding to convert his business into a high-end restaurant, Jonathan (a lawyer by training) was surprised how many details he had to pay attention to. In describing his learning journey, Jonathan said, ‘I was surprised at how much thought had to go into the design of a sought-after experience – for example, thinking when the maître d’ should greet the customer, when to take drink orders, how quickly to present menus.’ Jonathan had to work out how best to approach these aspects. Likewise, Charlie admitted that ‘the initial owner had many good ideas and a good concept of food,’ so Charlie and his partner learned from her but argued that ‘we knew how things should be done; we have seen where changes and improvements could be done.’

Simply put, engaging in entrepreneurship requires learning. Our restauranteurs had all perceived that pursuing their entrepreneurial opportunity was a complex task (more complex than they initially imagined). We next discuss how the entrepreneurs approached the tasks – that is, how they learned.

Learning modes – how do entrepreneurs learn?

Becoming a restauranteur was linked to different ways of acquiring knowledge and skills. We observed that our restauranteurs learned either by modelling others’ experience or by experimenting (alone and/or with others). Those with prior experience also learned from that experience.

Learning from experience

The most popular source of learning was learning from others. All four entrepreneurs engaged in modelling behaviours and adopted solutions used by other restauranteurs. While all talked about searching for inspiration from other restaurants and from books, three (Fredrik, Allan, Charlie) made very conscious decisions early in their careers to work in good restaurants and with renowned chefs either nationally or abroad in order to learn from them. For Fredrik, it was clear from the moment he decided to enter the profession that he wanted to learn from the best: ‘I did the restaurant school there [his home town], and then I moved to Gothenburg to Leif Mannerström, Sjömagasinet. I wanted to work with the best.’ He then moved to London to work with Richard Corrigan, chef and owner of the restaurant Lindsay House, who taught him to cook food that was simple but high in flavour. Fredrik’s restaurant concept is modelled on Richard’s approach. Later, shortly after Fredrik’s restaurant was awarded Restaurant of the Year in Sweden, he decided to copy Ferran Adria’s elBulli approach of constant experimentation: ‘We try to develop new things, similar to el Bulli, a restaurant in Spain which creates many new things with food, so we try to use it [their approach] here.’ Similarly, after attending culinary school, Allan moved to Reykjavik ‘because I got a contract as a trainee at the best restaurant at that time in Iceland … . Everything was made from scratch; it was a good school, very strict and very disciplined.’ Allan reflected that the demands he makes on his chefs and waiters probably reflect what he learned during his training there. He was also inspired by a trip to Italy. His wife confirmed, ‘It was after he returned from Italy that he decided to focus on local products. He learned this approach while in Italy. He seemed to be taken over by the philosophy.’ Allan continued to believe in the power of learning from others, adding, ‘We close the restaurant for January, and we go somewhere to get new ideas. Now, we are going to Berlin to get some ideas there … . We go out more to eat when abroad than in Iceland. We have been doing a lot of spying in the Nordic countries.’ Thus, observing what others were doing and learning from them was a continually attractive learning mode for Allan.

In contrast, Charlie decided to retain the existing concept when he purchased his restaurant from the previous owner. He said, ‘I really liked the concept – raw, rustic with a little homey atmosphere … and we kept the concept. The concept is very good and is working well.’ He explained, ‘I always wanted to run a restaurant, but I first wanted to gain experience,’ and he admitted that developing the restaurant further would require ‘a lot marketing work. I [would] need to travel very often to travel agencies and ask questions on what to improve … . Now we are looking for new projects.’ Jonathan’s behaviour shows a similar pattern. He developed his business concept by modelling concepts that appeared to be new, trendy, and successful. He started by establishing a discotheque when these were popular and then opened a hotel with a restaurant and a nightclub. In the early 1990s, he converted the hotel into a gourmet restaurant and boutique hotel following the fine-dining trend. He admitted, ‘I read lots of industry reports to understand the trends. This is how we decided what to do here.’

The chefs also relied on their own past experience as a source of learning. For example, his previous experience running a kitchen was helpful for Charlie and provided him with various solutions he was able to utilize as he engaged in his current business. In particular, Charlie used his prior knowledge of running a restaurant to quickly identify the mistakes that the prior owners had made and to identify possible solutions. He noted that ‘it only took us three to four months to start making a profit.’ When he and his business partner bought the restaurant, they implemented these fixes relying on their own past experience and focusing on becoming better and more efficient. In other words, they modelled what they already knew.

Learning by experimenting

Experimentation was a particularly interesting learning mode for two of our restauranteurs (Fredrik and Allan). For example, Fredrik explained that early on, he had to experiment with operations (e.g., frequency of paying invoices, purveying, etc.) because he did not really know how to organize these tasks, which initially had seemed straightforward. Over time, his experimentation became more conscious and focused on the offering and the revenue stream, as evidenced in the following quotes: ‘We try to develop new things. After I finished my sommelier education, we started to offer private parties for wine lovers where the food is developed to fit the wine of choice’ and ‘I believe that things should be done right, so I started to develop recipes and produce and sell sauces and vinaigrettes.’ Allan also engaged in conscious experimentation related to both marketing activities and developing new products and services. For example, once when the restaurant was very busy, he announced that he would waive everyone’s bills. In his view, this was a very successful marketing stunt that created a lot of buzz about the restaurant. Later, he offered cooking classes for individuals, with the idea that this would not only help market the restaurant and the delicatessen but also help better utilize the ingredients currently in stock. Allan’s experimentation involves also continuous search for novelty – ‘We experiment with ingredients. We cook traditional dishes with Icelandic ingredients. For example, pannacotta made of skyr.’ Through active experimentation, he carved a niche for himself. All of his suppliers said that Allan experiments but also pushes and encourages suppliers to experiment, develop new products, use new methods, etc. For example, his suppliers noted the following: ‘He is always seeking new ideas; he talks very much about local food’ (dairy supplier); ‘He likes to try new things … . They are really happy to try new things and tell us how they are’ (fishmonger); and ‘He always asks for new tastes’ (ice-cream maker).

The restauranteurs’ experimentation was often a collaborative learning practice. The evidence from our restauranteurs shows that they (Allan and Fredrik) actively engaged in collaborative experimentation with others in their social networks, mostly suppliers. For example, Allan engaged with his suppliers to develop new products. He approached his ice-cream supplier asking for new flavours and suggested sorrel – ‘We tried; it was green, and people liked it.’ They also developed garlic ice-cream, which Allan used in his soups in place of cream. On yet another occasion, after he decided to sell beer produced by a local micro-brewery, he asked his ice-cream supplier to work with the brewery to produce beer-flavoured ice-cream exclusively for his restaurant. Many of his suppliers confirmed that he asked them to develop exclusive products, as indicated by the following quotes: ‘We started to talk about new cheese, something only for him’ (dairy supplier) and ‘We have some special cuts and seasonings that we deliver exclusively to his restaurant’ (meat supplier). Fredrik also teamed up with some of his suppliers to develop new products to use in his restaurant. For example, his beef supplier explained, ‘Fredrik developed a recipe in his kitchen for a 100% beef sausage with no additives that we sell here and he uses in his restaurant.’ Later, they experimented together on a new concept for an upscale butcher’s shop that sells trimmed gourmet cuts of meat. From there emerged the idea of gourmet takeout. Fredrik explained, ‘We prepare raw ingredients for all the food lovers who want to cook their food at home. The package has all the ingredients, so they can do their steak and potatoes and prepare own bearnaise sauce at home.’ He added that this new space [takeout business] enabled him to do more food preparation for the restaurant so they could also open for lunch.

Strengthening relationships and trust with network partners led to increased learning through experimentation. Because our restauranteurs developed strong relationships with their suppliers, they were able to meet frequently and bounce around ideas. As such, it was often difficult to say where an idea originated. In the words of Allan’s ice-cream supplier, ‘It goes both ways; sometimes it is Allan who initiates, and sometimes it is us who suggest something. We are crazy sometimes too [smiling]. We work together.’ Then he added, ‘It is always a bit more exciting to work with places like Allan’s because you can do something, and you let him try and see what he can do with it.’ Similarly, Fredrik’s beef supplier said, ‘We are friends. We help each other. We discuss a lot, and we inspire each other.’

Interestingly, when learning from others, our restauranteurs highlighted former employers and chef peers as modelling sources. When experimenting with others, our restauranteurs worked mostly with suppliers and other partners in their networks and less with other chefs and restauranteurs. Additionally, we observed that experimenting with others helped strengthen relationships and increase innovativeness in the restauranteurs’ social networks. For example, Allan’s fish and seafood supplier said, ‘Through the years, we have not only been selling to them but also working with them in the other things. Our companies have certain bonds; we have some things that benefit both.’ Another of Allan’s suppliers mentioned that because of the bond that they have forged, ‘Our cooperation is much more than just sales. Just by speaking and sharing information, you get some resources.’ and ‘We look at them as our friends, and Allan’s restaurant is very loyal. I would take a coffee with him or something like that just to see how he is doing’. Fredrik expressed a similar opinion, saying, ‘With more and more producers, we have been in closer relationships.’ In other words, friendship emerges from these interactions. Conversely, the suppliers of the two restauranteurs who did not engage in much experimentation noted, ‘There is not so much connection’ (meat supplier to Charlie) and ‘They do not engage much’ (vegetable supplier to Jonathan).

Finally and somewhat surprisingly, we observed that after establishing their ventures and correcting any flaws, two of our restauranteurs (Charlie and Jonathan) did not engage in further active learning. It appears that they were not looking for new opportunities or ways to do things better or differently. While Charlie was more interested in looking for other projects – ‘We are exploring a new concept of a restaurant only for groups’ – Jonathan was satisfied with what he created. His supplier confirmed this, stating, ‘They are very similar throughout the years; the amounts they are buying are almost always the same.’ So, what influences whether entrepreneurs continue to learn and when they change how they learn? We explore these aspects next.

Analysis

To understand when the entrepreneurs relied on experimenting and when they learned from observing others, we explored how their perceptions of complexity and their perceived self-efficacy influenced their preferred learning mode. links elements of the entrepreneurial tasks that needed to be learned (learning needs), the perceived complexity of these tasks, and the learning modes adopted by the entrepreneurs.

Table 2. The Relationship between Perceptions of Complexity and Learning Mode (at the Start of the Entrepreneurial Journey)

It appears that the perceived complexity of the knowledge needed is one variable influencing the adoption of a particular learning mode. Our entrepreneurs realized that their entrepreneurial tasks consisted of many smaller tasks and that these subtasks varied in perceived difficulty. Our analysis shows that for more complex knowledge needs (e.g., the business concept or business model), the entrepreneurs tended to rely more on modelling, but for less complex knowledge needs (e.g., operations), they preferred experimentation. For example, the entrepreneurs realized that their business concepts consisted of complex configurations of multiple elements that needed to be in place simultaneously in order to generate the ambience and dining experience they sought and that developing these concepts did not lend itself to experimentation because these concepts needed to be in place upon restaurant launch. Indeed, developing these concepts could not be done in a piecemeal manner. The entrepreneurs modelled their concepts based on those that worked for others whom they respected (Fredrik modelled Richard Corrigan’s concept, Allan took inspiration from his trip to Italy, Jonathan followed industry trends, and Charlie retained the previous owner’s business concept). When the knowledge needs were simpler and could be developed along the way – for instance, value chain processes (e.g., orders, invoice payment), production processes (e.g., food processing, presentation techniques), and customer interactions (e.g., interactions between customers and wait staff, wine matching) – the entrepreneurs preferred to change or adapt others’ practices or develop their own practices based on their own experience (see ).

We observed that the entrepreneurs’ perceptions of the complexity of entrepreneurial tasks changed over time. More specifically, although the entrepreneurs’ initial business designs and value propositions were based on modelling behaviours and solutions they observed elsewhere, the process of matching their offerings to customer segments, which happened over time (in all cases at least three or four years into the business), involved more experimentation and the creation of new solutions. presents the value propositions the entrepreneurs developed over time and the learning modes used. For example, Allan’s value proposition included the addition of a delicatessen and cooking classes, Fredrik’s value proposition included the addition of participatory cooking and gourmet takeout, and Jonathan’s value proposition included themed weekends.

Table 3. The Relationship between Engagement in Networks and Preferred Learning Mode Over Time

To understand why the entrepreneurs’ perceptions of complexity changed, we analysed their perceived entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Before starting their restaurants, each of the four restauranteurs had successful careers. They considered themselves able and competent in the careers they were pursuing. For example, Charlie had been a restaurant manager, and Jonathan had owned a discotheque. This experience gave these two individuals confidence in their abilities to operate their own restaurants. In reflecting on their experience of starting their current businesses, they felt that this confidence was justified. Their prior experience gave them high levels of self-efficacy and enabled them to realize that they needed highly complex knowledge to run their new ventures. Neither experienced any major negative surprises when they started their current businesses, and they made little change to their original business models and operations.

However, Fredrik and Allan did not have such prior experience. As an accomplished chef (and a member of a national cooking team), Fredrik thought it was time to strike out on his own. His restaurant concept resembled one he had seen at one of his overseas employers. Having seen this previous employer run a successful restaurant gave him confidence that he would not experience many problems. Being self-efficacious and unaware of the complexity of the tasks, Frederik started by experimenting with operations. Although this experimentation helped him learn what worked and what did not, it made things difficult for him. He had to learn to make compromises among the diverse demands associated with the different roles he needed to perform, such as chef and restauranteur. Frederik’s lack of experience and knowledge about how to act in these situations and how to make some of the necessary decisions, combined with his high professional self-efficacy and pride, made him overconfident in his ability to run his business. In turn, this overconfidence pushed him to experiment rather than accept advice and employ others’ practices. This action was based on his assumption that the entrepreneurial tasks involved low complexity.

Frederik’s experimentation to solve some of the problems he faced was not always successful, which served to reduce his entrepreneurial self-efficacy. This experience not only made him realize the complexity involved in operating a successful business but also pushed him to adapt his learning mode – to model his former boss’s solutions. He admitted, ‘I went back to him [his friend and former boss] and asked how he deals with this?’ Thus, after an initial phase of experimenting, Fredrik focused on getting the different elements right, convincing customers about the validity of his concept, and dealing with other liabilities of newness. Gaining recognition from customers and food critics increased his confidence that he could be successful (e.g., ‘When we became the Restaurant of the Year, I suddenly believed anew that what we did made sense’) and resulted in his opening up and experimenting.

Like Fredrik, Allan embarked on running a restaurant convinced that it would be not much different from being an employed chef (overconfidence and illusion of control). He quickly realized that his assessment of the complexity involved in running a restaurant was inadequate and that the entrepreneurial tasks were more intricate than it had appeared initially. As Allan experienced various problems, he realized that his knowledge was limited but also that modelling solutions found elsewhere would allow him to introduce innovations and ideas without risking losing time and money developing something that did not work. His previous wide recognition (e.g., ‘For me, the highlight was when I was invited to cater for the presidential banquet in Reykjavik’) had boosted his self-efficacy and made running a restaurant appear relatively straightforward. Also, his meat supplier noted, ‘After people decided to trust him and started to believe in what he was saying, things have changed and he has changed.’ Consequently, feeling efficacious encouraged Allan to again start experimenting more and to offer his customers value they could not get elsewhere. The restaurant’s location in a small place with only one local newspaper in which to advertise meant Allan had to market his restaurant and its location. He used his influence to persuade local people in different businesses to come together to create a food cluster that would attract more customers to his and the other businesses (learning with others, cf. Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015).

Apart from our observation that the entrepreneurs’ different beliefs about their entrepreneurial efficacy influenced their learning mode, we also noticed that over time, the restauranteurs’ preferences changed although their tasks did not. For example, from early on, Fredrik had closely collaborated with renowned chefs and had modelled their behaviours when establishing his own restaurant concept. They created a sort of forum in which they could discuss problems and try to find solutions (i.e., learning from others). When Fredrik also became a renowned chef and owner of a restaurant ranked among the best in the country, he began to engage more in deliberate experimentation with new ideas. He forged close relationships with local suppliers to allow him to offer seasonal menus and develop new products (i.e., learning with others). For example, he introduced participatory cooking with customers, began serving lunches in 2009, and embarked on a side project with his beef supplier for gourmet takeout in 2011 (see for changes to the business model; see for key phases in his development as an entrepreneur). These developments suggest that the restauranteurs’ perceptions of what they could do (self-efficacy) changed over time. Simply put, entrepreneurial self-efficacy beliefs shape individuals’ preference for a particular learning mode. Next, we develop a contextualized model of entrepreneurial learning.

Table 4. Contextual Variables and Entrepreneurial Learning Modes

Developing a contextualized model of entrepreneurial learning

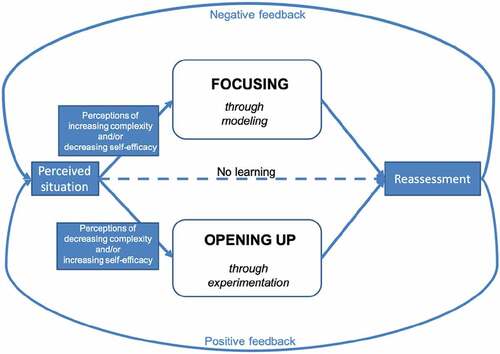

On the basis of our observations, we constructed a contextualized model of entrepreneurial learning (see ). Entrepreneurial learning starts with a perception of a situation – the entrepreneur assesses the situation by evaluating the perceived complexity of his or her entrepreneurial tasks. If the entrepreneur believes the complexity is too high and/or does not feel sufficiently efficacious, he or she will focus on searching for possible solutions and engaging in learning from others. However, if the entrepreneur believes the situation is simple and feels highly self-efficacious, he or she will open up and explore possibilities by engaging in experimentation. Based on feedback, the entrepreneur will then decide whether his or her initial assessment was correct or not and will adapt his or her learning mode if necessary. This means that the entrepreneur may employ one learning mode continuously or may switch among different modes. It is also possible that no learning will happen if the entrepreneur does not perceive that learning is required for the situation – for example, if there are no further opportunities to be pursued.

First, our model differentiates between two different processes that entrepreneurs engage in as they acquire new experience: focusing and opening up. We refer to the process involving a narrower focus on applying already proven solutions as focusing. For an entrepreneur with a more accurate assessment of the complexity of entrepreneurial tasks, the learning journey starts here. Because the entrepreneur understands the complexity of entrepreneurial tasks and feels relatively confident in his or her abilities, the entrepreneur begins by using existing knowledge. As the entrepreneur gains more experience in pursuing these tasks, his or her self-efficacy increases. This experience reduces the entrepreneur’s perception of the complexity of entrepreneurial tasks and, combined with high self-efficacy, triggers the entrepreneur to start exploring and experimenting. We refer to this experimentation with new ideas as opening up. This opening up can result in the development of new ideas, which – if judged to be feasible and desirable – provide continuous opportunities for learning. In other words, a preference for focusing (modelling) dominates if the entrepreneur has low self-efficacy and perceives the entrepreneurial tasks as highly complex, while a preference for opening up through experimentation will dominate if the entrepreneur has high self-efficacy and perceives the entrepreneurial tasks as relatively easy (low complexity).

Second, our model suggests that changing one’s learning mode requires experiencing some difficulty or some level of positive feedback that changes one’s perception of the context. Experiencing difficulties involves negative or less-than-satisfactory outcomes and is related to a focused search for solutions to an identified problem or need. Positive feedback comes from the entrepreneur’s network and is associated with the exploratory search for new ideas or ways of acting (alone or with others).

Third, our model highlights that the entrepreneur’s initial assessment of the complexity of the entrepreneurial tasks may or may not be adequate. More specifically, experienced entrepreneurs are likely to make more accurate assessments of complexity based on their prior experience, while inexperienced entrepreneurs are more likely to make inadequate initial assessments of the complexity of the entrepreneurial tasks, particularly if they are successful professionals (as in the cases of Fredrik and Allan). As a less experienced entrepreneur realizes that the entrepreneurial tasks are more complex than he or she originally estimated, this increased complexity is perceived as a problem and encourages the entrepreneur to focus on and utilize existing models and solutions – that is, to learn from others by modelling.

Finally, our model responds to calls for a better understanding of the learning process; it shows that learning is contextual and that entrepreneurs adapt their learning modes (experimentation and modelling) to the contextual variables. We also show that entrepreneurial learning is collaborative and that network embeddedness facilitates this process (Cope Citation2011; Korsgaard Citation2011; Korsgaard, Ferguson, and Gaddefors Citation2015; Lechner and Dowling Citation2003; Taylor and Thorpe Citation2004).

Discussion

A basic premise of our paper is that despite increased interest in the entrepreneurial learning process, the temporal and process dimensions have received insufficient consideration (Wang and Chugh Citation2014). In their literature review, Wang and Chugh (Citation2014) note the need to integrate learning from opportunity exploration with learning from opportunity exploitation, particularly after market entry, as well as the need for a more collective social approach to learning. In this paper, we take a step towards unpacking the contextual nature of entrepreneurial learning by (1) conducting a longitudinal exploration of the process in its socioeconomic spatial context, (2) mapping sequential changes in entrepreneurs’ preferences for a specific learning mode and identifying the contextual variables influencing those changes, (3) highlighting perceived complexity as a key variable influencing entrepreneurs’ preferred learning mode, (4) specifying how different configurations of self-efficacy beliefs and perceived task complexity influence entrepreneurs’ learning mode preferences over time, and (5) depicting the role of networks in this process. More specifically, on the basis of in-depth case studies of four Scandinavian fine-dining entrepreneurs, we develop a contextualized model of experiential entrepreneurial learning.

This work contributes to the entrepreneurial learning literature by conceptualizing entrepreneurial learning as a contextualized social process that occurs over time, in which changing perceptions of task complexity and self-efficacy guide individuals’ preference for either modelling or experimentation. This variability in preferences and its temporal aspect have not been discussed in the literature so far.

Research implications

Some recent works have proposed entrepreneurial learning as a complex process that is embedded contextually (Jack and Anderson Citation2002; Toutain et al. Citation2017) and is the result of the interaction between the individual and his or her social context (Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015; Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017). We contribute to this view, by exploring how contextual variables influence the learning process.

Our study provides various novel insights that contribute to the literature. First, we show that in the course of pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurs engage in opening-up and focusing processes. While opening up is related to exploratory learning mainly through experimentation, focusing refers to modelling related to problem solving and performance improvements. Thus, opening up is akin to exploration, and focusing is akin to exploitation (Politis Citation2005). Our findings also suggest that modelling provides entrepreneurs legitimacy and enables them to fit their venture to current norms and ways of doing business, while experimentation enables them to create distinctiveness and uniqueness. Overall, our findings provide evidence that regardless of the existence of or lack of prior entrepreneurial knowledge, entrepreneurs go through a focusing phase in which they either replicate their own earlier behaviour or model others’ behaviours. The preference for modelling is also explained by optimal distinctiveness theory (cf. Shepherd and Haynie, Citation2009) and in the context of legitimacy-seeking behaviours (Barreto & Baden-Fuller, Citation2006). Entrepreneurs revert to known strategies and concepts to reduce their level of uncertainty and ensure market acceptance. Thus, it could be argued that this initial focus on modelling helps entrepreneurs reduce the complexity of the task and satisfy their need to belong to a community (of chefs in our case), which may be important to signal their origins and belongingness.

Second, our findings show how learning modes change over time. Extant research has acknowledged the existence of participative (experiential) and observational (i.e., learning from others) learning (Choi, Lévesque, and Shepherd Citation2008; Lévesque, Minniti, and Shepherd Citation2009) and has implicitly assumed that they are stable over time. Our research reveals the contextual conditions under which learning modes (experimentation and modelling) that once seemed appropriate and useful become less effective. Specifically, we show that the transition from experimentation to modelling occurs because, following an initial period of experimentation, entrepreneurs realize that the complexity of the entrepreneurial tasks is higher than they anticipated. Modelling then offers a more effective and less risky strategy for exploiting opportunities (Holcomb et al. Citation2009; Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017). This process saves time and money. Conversely, experienced entrepreneurs who are strongly embedded in professional networks realize that experimentation will likely make them distinctive in their profession by generating (i.e., co-creating) new value propositions that will attract the recognition of peers, gain prestige among customers, and result in awards. Further, we show that experienced entrepreneurs with high levels of self-efficacy who actively engage in building strong relationships within their professional and local networks reduce their involvement in modelling and intensify their experimentation efforts over time. This mode of learning allows entrepreneurs to open up, explore new avenues, and test the accepted rules of the game. It seems that entrepreneurs engage in this learning mode once their initial operations and business models have stabilized and appear to be reasonably successful. In other words, learning preferences change over time, shifting from experimentation to modelling and then back again, but they change less when entrepreneurs are weakly embedded and weakly engaged in their networks.

Third, we show that learning mode preferences depend on entrepreneurs’ level of perceived self-efficacy and perceptions of the complexity of the task at hand. Specifically, low self-efficacy leads entrepreneurs to choose modelling, while increased self-efficacy promotes the use of experimentation. Further, high perceived complexity encourages modelling, while experimentation appears to be a more viable learning strategy for tasks perceived as less complex. Our data show that in the case of low levels of self-efficacy, individuals prefer modelling because they do not trust their own judgement and therefore consider personal experience as a less relevant learning mode (Wood and Bandura Citation1989). When they become more successful and more confident in their abilities, experiential learning dominates modelling. Extant research has suggested that prior experience and learning (e.g., formal learning and learning from the example of others) are important for increasing self-efficacy beliefs and the intention to become an entrepreneur (Engel et al. Citation2014; Zhao, Seibert, and Hills Citation2005). Like most entrepreneurs, those we studied had extensive experience with both the industry they entered and the relevant work tasks associated with operating the businesses they started. Initially, driven by their high professional self-efficacy, they vastly underestimated the complexities of their business models and the efforts needed to learn about them. Essentially, they believed that the role of entrepreneur (i.e., running a restaurant in this case) was quite similar to the role of employee. They jumped into entrepreneurship, figuring they could learn by experimentation. When things did not turn out as expected, their perceptions of the complexity involved in running a restaurant increased, their self-efficacy decreased, and they resorted to learning about their business models by modelling others and to focusing on identifying and learning about the core activities of their businesses. Our findings suggest that entrepreneurial self-efficacy is domain efficacy and that entrepreneurs’ initial behaviours seem to be consistent with an overconfidence bias in their ability to manage the complexity of the entrepreneurial tasks. Holcomb et al. (Citation2009) observe that under uncertainty, decision heuristics play an important role in the entrepreneurial learning process. Overconfidence bias is one such heuristic, and higher self-efficacy is likely associated with greater overconfidence (e.g., Forbes Citation2005). Although overconfidence increases individuals’ willingness to engage in entrepreneurial behaviour (Engel et al. Citation2014), it may be detrimental to entrepreneurs’ ability to learn from the process initially because it entices entrepreneurs into believing that their knowledge is more relevant than it is and reduces their willingness to learn by modelling others. More importantly for our learning model, our research suggests that both entrepreneurial self-efficacy and perceived complexity are important for entrepreneurs’ choice of learning mode.

Fourth, with regard to the contextualized nature of entrepreneurial learning, our data extends current understanding. We show that entrepreneurs who actively build strong ties in their networks also engage more in joint experimentation activities. In our specific cases, some of the entrepreneurs included other chefs, suppliers, and/or members of their local networks to experiment jointly with them, and they learned with others, while the chefs who retained their networks for functional use did not include others in their experimentation, if they experimented at all. This is an interesting finding that should encourage future research. Indeed, prior entrepreneurship research has emphasized that entrepreneurs can obtain resources from their social networks (Zozimo, Jack, and Hamilton Citation2017) but has been relatively silent about what entrepreneurs give back. Our results show that deep embeddedness in professional networks stimulates experimentation. Others can then learn from this experimentation, which in turn provides entrepreneurs with stronger and more central positions in their networks. In other words, purposeful professional embeddedness increases entrepreneurs’ ability to identify with professional role models and facilitates learning (Jack, Dodd, and Anderson Citation2008; Jones, Macpherson, and Thorpe Citation2010; Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015). Being connected to role models and prestigious professional ties influence the effort entrepreneurs invest in developing their business concepts and lead to more rapid and extensive learning. This embeddedness is likely to increase the transfer of resources in general and the transfer of tacit and complex knowledge in particular since close contacts are generally more willing to take time to explain processes in detail or to listen to novel and complex ideas (Anderson and Jack Citation2002; Moran Citation2005). The extent to which the involved parties understand each other enables and supports the transfer of tacit and complex knowledge and enables the communication of non-codified knowledge (Uzzi Citation1997).

Limitations and outlook

This research relies on case studies of Scandinavian entrepreneurs in the fine-dining segment of the restaurant industry. The empirical generalizability of our work is limited and was not an objective of our study. Our identification of what entrepreneurs learn and their changing preferences for different modes of acquiring knowledge based on the perceived characteristics of the task at hand is based on general learning theories and should therefore be more generalizable. We also believe that the pattern of change in perceptions of task complexity and level of self-efficacy experienced over time is likely to be general and is reflective of dealing with uncertainty in various aspects of life. However, as with any theory, the model should be subjected to systematic empirical testing in order to determine the empirical validity and generalizability of our proposed theory.

Our model suggests that entrepreneurs are more likely to use experimentation for tasks they perceive as less complex, while modelling appears to be a more viable learning strategy for tasks they perceive as more complex. This finding may appear counterintuitive and contrasts with the commonly held view that less complex tasks are easier to imitate and model based on the assumption that high levels of complexity and tacitness impede opportunities for observation and successful knowledge transfer (e.g., Holcomb et al. Citation2009). Our findings clearly show that when dealing with situations they perceive as complex and uncertain, entrepreneurs prefer to model behaviours they have seen applied by others and solutions they have seen elsewhere. Despite being able to imitate only the observable elements of the task at hand, entrepreneurs appear to perceive modelling as a strategy that reduces uncertainty, thereby providing greater safety. It allows them to focus on replicating observable elements that they deem important. In other words, the relative uncertainty of the situation and the fear of losing control over outcomes due to perceived complexity seem to push entrepreneurs to adopt existing solutions, while choices they perceive as simple seem to encourage them to experiment. This finding suggests interesting avenues for future research to explore the differences between perceived task complexity and objective task complexity and subsequent risks, fallacies, and biases in judgements (decision making). For example, it would be interesting to further explore how the degree of overconfidence (i.e., the extent to which perceived complexity is lower than objective complexity) influences entrepreneurial learning.

We also show that as entrepreneurs become more self-efficacious, they engage in more experimentation because it offers the possibility to identify new opportunities and helps them demonstrate their own uniqueness. Nevertheless, despite showing high levels of self-efficacy, two of our entrepreneurs (Charlie and Jonathan) did not actively engage in experimentation. Thus, future research could investigate what reduces entrepreneurs’ willingness to experiment despite high levels of self-efficacy.

Finally, as observed by Frankish et al. (Citation2012), not all entrepreneurs seem to learn from their experience; rather, they tend to repeat the same mistakes. In terms of our proposed model, a likely reason for the lack of learning during the early phases of the entrepreneurial journey might be failure to realize the complexity of the entrepreneurial task compared to initial expectations and therefore failure to realize the need to engage in a focused learning process by changing from experimentation to modelling others’ behaviour. Another reason might be overconfidence (Forbes Citation2005). Individuals who consider themselves experts in their domain may fail to recognize that entrepreneurial endeavours require the acquisition of additional knowledge and skills. Further analysis of the relationship between the types of mistakes entrepreneurs make and the learning modes they prefer could shed additional light on the effectiveness of the two learning methods to deal with different learning needs.

Note

Kolb’s (Citation1984) experiential learning theory assumes that experience is available for entrepreneurs – namely, that they learn either from direct experience or through conceptualization. We argue that Bandura’s theory is more applicable in the entrepreneurship context because it does not assume the availability of experience. The forethought, intentionality, and the interplay of environmental, personal, and behavioural factors allow for this openness and variation in the acquisition of new experience.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, A. 2000. “Paradox in the Periphery: An Entrepreneurial Reconstruction?” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 12: 91–109. doi:10.1080/089856200283027.

- Anderson, A., and S. Jack. 2002. “The Articulation of Social Capital in Entrepreneurial Networks: A Glue or A Lubricant?.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 14: 193–210. doi:10.1080/08985620110112079.

- Bandura, A. 1977a. “Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behaviour Change.” Psychological Review 84: 191–215. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191.

- Bandura, A. 1977b. Social Learning Theory. Eaglewoods Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: Freeman.

- Bandura, A. 2001. “Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective.” Annual Review Pychology 52: 1–26. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1.

- Barreto, I., and C. Baden-Fuller. 2006. “To Conform or to Perform? Mimetic Behaviour, Legitimacy-based Groups and Performance Consequences.” Journal Of Management Studies 43 (7): 1559-1581. doi:10.1111/joms.2006.43.issue-7.

- Baum, J., S. Li, and J. Usher. 2000. “Making the Next Move: How Experiential and Vicarious Learning Shape the Locations of Chains’ Acquisitions.” Administrative Science Quarterly 45 (4): 766–801. doi:10.2307/2667019.

- Bosma, N., J. Hessels, V. Schutjens, M. V. Praag, and I. Verheul. 2012. “Entrepreneurship and Role Models.” Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2): 410–424. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004.

- Choi, Y. R., M. Lévesque, and D. A. Shepherd. 2008. “When Should Entrepreneurs Expedite or Delay Opportunity Exploitation?.” Journal of Business Venturing 23 (3): 333–355. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.11.001.

- Cope, J. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Learning from Failure: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (6): 604–623. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002.

- Corbett, A. 2005. “Experiential Learning within the Process of Opportunity Identification and Exploitation.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29 (4): 473–491. doi:10.1111/etap.2005.29.issue-4.

- Dalborg, C., and J. Wincent. 2015. “The Idea Is Not Enough: The Role of Self-efficacy in Mediating the Relationship between Pull Entrepreneurship and Founder Passion – A Research Note.” International Small Business Journal 33 (8): 974–984. doi:10.1177/0266242614543336.

- Dempsey, D., and J. Jennings. 2014. “Gender and Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy: A Learning Perspective.” International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 6 (1): 28–49. doi:10.1108/IJGE-02-2013-0013.

- Drnovšek, M., J. Wincent, and M. Cardon. 2010. “Entrepreneurial Self‐efficacy and Business Start‐up: Developing a Multi‐dimensional Definition.” International Journal Of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 16 (4): 329–348. doi:10.1108/13552551011054516.

- Eisenhardt, K., and M. E. Graebner. 2007. “Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges.” Academy of Management Journal 50 (1): 25–32. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160888.

- Engel, Y., N. G. Dimitrova, S. N. Khapova, and T. Elfring. 2014. “Uncertain but Able: Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy and Novices׳ Use of Expert Decision-logic under Uncertainty.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 1–2 12–17. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2014.09.002.

- Erikson, T. 2003. “Towards a Taxonomy of Entrepreneurial Learning Experiences among Potential Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 10: 106–112. doi:10.1108/14626000310461240.

- Forbes, D. 2005. “Are Some Entrepreneurs More Overconfident than Others?” Journal of Business Venturing 20: 623–640. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.05.001.

- Frankish, J. S., R. G. Roberts, A. Coad, T. C. Spears, and D. J Storey. (2012). Do entrepreneurs really learn? Or do they just tell us that they do? Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(1), 73–106. doi:10.1093/icc/dts016.

- Gioia, D., K. Corley, and A. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Hjorth, D. 2004. “Creating Space for Play/invention – Concepts of Space and Organizational Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 16 (5): 413–432. doi:10.1080/0898562042000197144.

- Holcomb, T., R. D. Ireland, R. M. Holmes Jr, and N. A. Hitt. 2009. “Architecture of Entrepreneurial Learning: Exploring the Link among Heuristics, Knowledge, and Action.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 33 (1): 167–192. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00285.x.

- Jack, S. 2005. “The Role, Use and Activation of Strong and Weak Network Ties: A Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of Management Studies 42 (6): 1233–1259. doi:10.1111/joms.2005.42.issue-6.

- Jack, S., and A. Anderson. 2002. “The Effects of Embeddedness on the Entrepreneurial Process.” Journal of Business Venturing 17 (5): 467–487. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3.

- Jack, S., S. D. Dodd, and A. Anderson. 2008. “Change and the Development of Entrepreneurial Networks over Time: A Processual Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 20 (2): 125–159. doi:10.1080/08985620701645027.

- Jones, O., A. Macpherson, and R. Thorpe. 2010. “Learning in Owner-managed Small Firms: Mediating Artefacts and Strategic Space.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22 (7): 649–673. doi:10.1080/08985620903171368.

- Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential Learning: Experiences as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ,: Prentice Hall.

- Korsgaard, S. 2011. “Entrepreneurship as Translation: Understanding Entrepreneurial Opportunities through Actor-network Theory.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (7–8): 661–680. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.546432.

- Korsgaard, S., R. Ferguson, and J. Gaddefors. 2015. “The Best of Both Worlds: How Rural Entrepreneurs Use Placial Embeddedness and Strategic Networks to Create Opportunities.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (9–10): 574–598. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1085100.

- Krueger, N. 2007. “What Lies Beneath? the Experiential Essence of Entrepreneurial Thinking.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (1): 123–138. doi:10.1111/etap.2007.31.issue-1.

- Lechner, C., and M. Dowling. 2003. “Firm Networks: External Relationships as Sources for the Growth and Competitiveness of Entrepreneurial Firms.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 15 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1080/08985620210159220.

- Lefebvre, V., M. Radu Lefebvre, and E. Simon. 2015. “Formal Entrepreneurial Networks as Communities of Practice: A Longitudinal Case Study.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (7–8): 500–525. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1070539.

- Lévesque, M., M. Minniti, and D. Shepherd. 2009. “Entrepreneurs’ Decisions on Timing of Entry: Learning from Participation and from the Experiences of Others.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (2): 547–570. doi:10.1111/etap.2009.33.issue-2.

- Markowska, M. 2018. “An Entrepreneurial Career as a Response to Seeking a Career Challenge: The Case of Gourmet Chefs.” In Seeking Challenge in the Career, edited by S. G. Baugh and S. E. Sullivan. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing. p. 49-75

- Markowska, M., and H. Lopez-Vega. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Storying: Winepreneursas Crafters of Regional Identity Stories.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 19 (4): 282–297. doi:10.1177/1465750318772285.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 1995. Designing Qualitative Research 2 Ed.. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- McKeever, E., A. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2014. “Entrepreneurship and Mutuality: Social Capital in Processes and Practices.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (5–6): 453–477. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.939536.

- McMullen, J., and D. Shepherd. 2006. “Entrepreneurial Action and the Role of Uncertainty in the Theory of the Entrepreneur.” Academy of Management Review 31 (1): 132–152. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.19379628.

- Miao, C., S. Qian, and D. Ma. 2017. “The Relationship between Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy and Firm Performance: A Meta-Analysis of Main and Moderator Effects.” Journal of Small Business Management 55 (1): 87–107. doi:10.1111/jsbm.2017.55.issue-1.

- Moran, P. 2005. “Structural Vs. Relational Embeddedness: Social Capital and Managerial Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 26: 1129–1151. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0266.

- Morris, M., D. Kuratko, M. Schindehutte, and A. Spivack. 2012. “Framing the Entrepreneurial Experience.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (1): 11–40. doi:10.1111/etap.2012.36.issue-1.

- Muehlfeld, K., P. Rao Sahib, and A. Van Witteloostuijn. 2012. “A Contextual Theory of Organizational Learning from Failures and Successes: A Study of Acquisition Completion in the Global Newspaper Industry, 1981–2008.” Strategic Management Journal 33 (8): 938–964. doi:10.1002/smj.v33.8.

- Nanda, R., and J. B. Sørensen. 2010. “Workplace Peers and Entrepreneurship.” Management Science 56 (7): 1116–1126. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1100.1179.

- Newman, A., M. Obschonka, S. Schwarz, M. Cohen, and I. Nielsen. 2018. “Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy: A Systematic Review of the Literature on Its Theoretical Foundations, Measurement, Antecedents, and Outcomes, and an Agenda for Future Research.” Journal of Vocational Behavior. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2018.05.012.

- Pittaway, L., and R. Thorpe. 2012. “A Framework for Entrepreneurial Learning: A Tribute to Jason Cope.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24 (9–10): 837–859. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.694268.

- Politis, D. 2005. “The Process of Entrepreneurial Learning: A Conceptual Framework.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 29 (4): 399–424. doi:10.1111/etap.2005.29.issue-4.

- Rao, H., P. Monin, and R. Durand. 2005. “Border Crossing: Bricolageand the Erosion of Categorical Boundariesin French Gastronomy.” American Sociological Review 70 (6): 968–991. doi:10.1177/000312240507000605.

- Schumpeter, J. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Boston: Harvard University Press.

- Shepherd, D. 2009. “Birds Of a Feather Don't Always Flock Together: Identity Management in Entrepreneurship.” Journal Of Business Venturing 24 (4): 316–337.

- Shepherd, D., and K. M. Sutcliffe. 2011. “Inductive Top-Down Theorizing: A Source of New Theories of Organization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (2): 361–380.

- Shinnar, R. S., D. K. Hsu, and B. C. Powell. 2014. “Self-efficacy, Entrepreneurial Intentions, and Gender: Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Longitudinally.” The International Journal of Management Education 12 (3): 561–570. doi:10.1016/j.ijme.2014.09.005.

- Strandgaard Pedersen, J., S. Svejenova, C. Jones, and P. De Weerd-Nederhof. 2006. “Editorial to Special Issue on Transforming Creative Industries: Strategies of and Structures around Creative Entrepreneurs.” Creativity and Management 15: 21–23.

- Taylor, D., and R. Thorpe. 2004. “Entrepreneurial Learning: A Process of Co-participation.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11 (2): 203–211. doi:10.1108/14626000410537146.

- Toft-Kehler, R., K. Wennberg, and P. H. Kim. 2014. “Practice Makes Perfect: Entrepreneurial-experience Curves and Venture Performance.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (4): 453–470. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.001.

- Toutain, O., A. Fayolle, L. Pittaway, and D. Politis. 2017. “Role and Impact of the Environment on Entrepreneurial Learning.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29 (9–10): 869–888. doi:10.1080/08985626.2017.1376517.

- Ucbasaran, D., M. Wright, and P. Westhead. 2003. “A Longitudinal Study of Habitual Entrepreneurs: Starters and Acquirers.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 15 (3): 207–228. doi:10.1080/08985620210145009.

- Uzzi, B. 1997. “Social Structure and Competition in Intrafirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 35–67. doi:10.2307/2393808.

- Wang, C. L., and H. Chugh. 2014. “Entrepreneurial Learning: Past Research and Future Challenges.” International Journal of Management Reviews 16 (1): 24–61. doi:10.1111/ijmr.2014.16.issue-1.

- Wolcott, H. F. (1990). Writing up qualitative research. (Vol. 20). USA: Sage Publications.

- Wood, R. E., and A. Bandura. 1989. “Impact of Comception of Ability on Self-regulatory Mechanisms and Complex Decision Making.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 56 (3): 407–415. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.3.407.

- Zahra, S. A., M. Wright, and S. G. Abdelgawad. 2014. “Contextualization and the Advancement of Entrepreneurship Research.” International Small Business Journal 32 (5): 479–500. doi:10.1177/0266242613519807.