ABSTRACT

This paper sets out to better understand the role of ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship, in particular in terms of intersections at the boundaries between ‘ethnic’ and ‘mainstream’ economies, internal differentiation within ethnic community boundaries, and the socially constructed nature of ethnic boundaries more broadly. To better account for these dynamics, we develop a Barthian perspective on immigrant entrepreneurship, building on and integrating Fredrik Barth’s work on entrepreneurship, ethnic boundaries, and spheres of value. A Barthian perspective shifts the analytic focus from the ethnic group to entrepreneurial activities and, by implication, to the ethnic boundary dynamics that these activities generate. We draw on ethnographic research conducted among immigrant Mennonite entrepreneurs in Belize, and identify three boundary dynamics among the Mennonites: bridging the boundary between Mennonite ethnicity and the wider Belizean society, stretching the boundaries of individual Mennonite communities, and allying across the boundaries between Mennonite communities. In developing a Barthian perspective, the contribution of our paper lies in developing a comprehensive framework for understanding the role of ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship, thereby also responding to calls for more micro-processual approaches to understanding the ‘mixed embeddedness’ of immigrant entrepreneurs in their ethnic community and the wider society contexts.

1. Introduction

Abraham ZimmermanFootnote1 is a Mennonite entrepreneur who grows rice in Belize, a small country in Central America. In 1958, Mr. Zimmerman was among the first Mennonites who came to Belize through Mexico, where the state was forcing them to assimilate further in mainstream society, while, by way of a tacit agreement, Belizean authorities offered religious and cultural autonomy in return for the production of cash crops and meat, hence rendering Belize less dependent on imports. Mennonites are Anabaptists adhering to an Ordnung (religious-moral code) that varies in strictness across different communities, which are today scattered throughout different settlements in Belize. Upon arrival, Mr. Zimmerman’s parents helped found the settlement of Shipyard to build a life within the Old Colony community, which prohibits the use of many modern technologies. By 1977, however, to be able to till his land properly, he began using ‘modern’ rubber tires on his tractor instead of the approved steal tires. This upset the Old Colony Älteste (eldest) and Prediger (preacher) so much that he was ausgeschlossen (excommunicated). According to the preacher, ‘he could have stayed in the community if he had repented and asked for forgiveness’, but Mr. Zimmerman would not budge. The latter recalls: ‘I said to them, “I will not take them off”. It was all very sad.’ Mr. Zimmerman maintained his business in Shipyard but later registered with the less conservative church of the Kleine Gemeinde community, which allowed him to use rubber tires. He and his family now have to drive one hour every Sunday to visit their new church in the settlement of Blue Creek. No longer constrained by the religious-moral code of the conservative Old Colony community, however, Mr. Zimmerman’s business thrives as he sells his rice across Belize.

If entrepreneurship is the ‘creation and extraction of value from an environment’ (Anderson Citation2000, 91), then value creation in immigrant entrepreneurship has long been considered to emerge from within the boundaries of the ethnic community. Early studies argue that migrants rely on trust-based relationships within their community for investment and credit, ideas, expertise, labour and consumer markets (e.g. Aldrich and Waldinger Citation1990; Portes and Sensenbrenner Citation1993). More recent studies instead point out that immigrant entrepreneurship is not only contingent upon ethnic community resources, but also on the adopted society, including ties to ethnic ‘others’ and society’s institutional framework and opportunity structure (Basu Citation2011; Eraydin, Tasan-kok, and Vranken Citation2010; Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018; Ram, Theodorakopoulos, and Jones Citation2008). The appeal of the ‘mixed embeddedness’ perspective (Kloosterman, van der Leun, and Rath Citation1999) best illustrates the emerging consensus among scholars that immigrant entrepreneurship is embedded in both ethnic community and mainstream society.

Yet, the case of Mr. Zimmerman is not satisfactorily explained by his mixed embeddedness in Mennonite community and Belizean society. After all, value creation does not occur as a result of his mixed embeddedness as such, but rather because he operates at, challenges, and ultimately transgresses the ethnic boundaries implied in mixed embeddedness. Within the multicultural society of Belize, Mr. Zimmerman draws on a Mennonite repertoire to start a company, but subsequently creates value by pushing the boundaries of what is considered morally appropriate within the conservative community, transgressing those boundaries, moving to a more progressive Mennonite community as a result and, again, operating at ethnic boundaries, this time between the progressive Mennonite community and the wider Belizean market and society. Mr. Zimmerman creates value by seeking out, sometimes failing, and sometimes achieving to negotiate the boundary between his ethnic-religious community and the other socio-economic spheres where he spots an opportunity, which raises tensions because what is good for Mr. Zimmerman’s company may be disapproved of or even forbidden by the community.

Mr. Zimmerman’s case thus directs our empirical attention away from the question of whether he is embedded in ethnic community or wider society per se, and towards ethnic boundaries, where he balances communal constraints and looming economic opportunities. To date, however, ‘few studies take into account the complexity of ethnic boundary-making, especially in relation to business interactions’ (Pécoud Citation2010, 65). This neglect of ethnic boundaries in immigrant entrepreneurship literature, as critical scholars have pointed out, is problematic for three reasons: it falsely presumes a clear distinction between ‘ethnic’ and ‘mainstream’ economies (Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018; Nederveen Pieterse Citation2003), glosses over internal differentiation within ethnic communities (Ram, Jones, and Villares-Varela Citation2017; Romero and Valdez Citation2016), and disregards the socially constructed nature of ethnicity (Aldrich and Waldinger Citation1990; Jones and Ram Citation2007).

This paper sets out to better understand the role of ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship. Building on ethnographic research among different Mennonite communities in Belize, we show that entrepreneurial activities generate three distinct boundary dynamics: bridging the boundary between Mennonite ethnicity and the wider Belizean society, stretching the boundaries of individual Mennonite communities, and allying across the boundaries between Mennonite communities. We draw on the seminal work of Fredrik Barth, who has extensively written on ethnicity (Citation1969) as well as entrepreneurship (Citation1963, Citation[1967] 2000), to explain and theorize these boundary dynamics. In doing so, we shift the analytic focus from the ethnic community level to micro-level immigrant entrepreneurial activities, and thus arrive at a perspective that centres around, rather than neglects, ethnic boundary dynamics.

By fleshing out a Barthian perspective, our contribution is twofold. First, we respond to calls for more micro-processual approaches to mixed embeddedness (Peters Citation2002; Storti Citation2014; Wang and Warn Citation2018), recognizing that a dominant focus on outcomes at the ethnic group level has left the processes by which migrant business ventures are formed understudied (Dheer Citation2018). Our second contribution lies in a critical reappraisal of the role of ethnic boundaries in immigrant entrepreneurship. A number of previous studies reveal micro-level ethnic dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship, describing internal differentiation within ethnic groups (Romero and Valdez Citation2016; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011), business engagements across ethnic groups (Arrighetti, Bolzani, and Lasagni Citation2014; Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018), and the negotiation of existing identities or practices within ethnic groups (Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Ram et al. Citation2003). Implicitly or explicitly, these studies challenge static understandings of ethnic boundaries in immigrant entrepreneurship. Yet, while literature to date remains fragmented (Pécoud Citation2010), we integrate insights from these empirical studies, critical reviews in the field (e.g. Danes et al. Citation2008; Pécoud Citation2000; Rath Citation2000) and the work of Barth (Citation1963, Citation1969, Citation[1967] 2000) to develop a comprehensive framework for understanding ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship.

2. Literature review: ethnic boundaries in immigrant entrepreneurship studies

Early studies argued that immigrants rely on ‘bounded solidarity’ and ‘enforceable trust’ within ethnic communities to engage in economic transactions (Portes and Sensenbrenner Citation1993, 1324–1325; cf. Aldrich and Waldinger Citation1990). These studies have decided the contours of immigrant entrepreneurship studies and spurred notions of ethnic economies, enclaves and middlemen minorities that operate ‘outside’ the national economy (Zhou Citation2004; cf. Fairchild Citation2010). Other scholars observe in these studies an overemphasis on migrant community factors and seek to counter the tendency to ‘reduce immigrant entrepreneurship to an ethnocultural phenomenon’ (Rath and Kloosterman Citation2000, 666; cf. Jones and Ram Citation2007). Especially in European scholarship, consensus is emerging around the mixed embeddedness perspective since the turn of the millennium, and hence around the idea that immigrant entrepreneurs are embedded in their ethnic community as well as the wider society (Ram, Jones, and Villares-Varela Citation2017).

In its original formulation (Kloosterman, van der Leun, and Rath Citation1999), mixed embeddedness connotes that, next to personal resources derived from co-ethnic networks, immigrant entrepreneurs are especially dependent on the opportunity structure of markets, where migrants have to compete with established indigenous firms, and on the rules and restrictions set by the state (Kloosterman and Rath Citation2001; Ram, Jones, and Villares-Varela Citation2017). Others have expanded mixed embeddedness to include the relational level (Ram, Theodorakopoulos, and Jones Citation2008), similarly arguing that immigrant entrepreneurs rely on connections within and beyond their ethnic group – for example when hiring employees or targeting consumers (Basu Citation2011; Drori and Lerner Citation2002) – or develop both strong ties within their community as well as weak ties outside it to the benefit of their business (Eraydin, Tasan-kok, and Vranken Citation2010). In the context of transnational economic activities, yet other scholars make the case for a ‘simultaneous embeddedness’ perspective that considers these factors in both the host and home country of migrants (Nazareno, Zhou, and You Citation2019). Another opportunity lies in developing more micro-processual approaches that focus on actual entrepreneurial activities (Peters Citation2002; Storti Citation2014; Wang and Warn Citation2018), which – surprisingly considering the subject matter – have largely been neglected in immigrant entrepreneurship literature to date (Dheer Citation2018; Jones and Ram Citation2007; Ma et al. Citation2013). By developing a Barthian perspective, in this paper we respond especially to this latter opportunity to advance the mixed embeddedness literature, but first we will discuss representations of ethnic boundaries in immigrant entrepreneurship literature.

Ethnic community boundaries are often presented as static, while in fact such boundaries are inherently dynamic and porous (Nederveen Pieterse Citation2003; Pécoud Citation2010). As Brubaker notes about studies of ethnicity and migration broadly, these tend to regard categories of people as ‘internally homogeneous, externally bounded groups’ and take these as ‘fundamental units of social analysis’ (Citation2009, 28; cf. Wimmer Citation2008). This tendency is also observed in immigrant entrepreneurship studies (Danes et al. Citation2008; Pécoud Citation2000; Rath Citation2000; Romero and Valdez Citation2016). Most studies inquire into community characteristics – investigating for example rates of self-employment (as a proxy for entrepreneurship), network endowments, performance differences, or concentration in economic niches (Aliaga-Isla and Rialp Citation2013) – and especially into the differences between communities on the national level (Danes et al. Citation2008). As we describe below, critical scholars have identified three ways in which such a focus on ethnic groups is problematic when we consider the dynamics of ethnic boundaries, and suggest corresponding avenues for moving beyond such ‘groupism’ (Brubaker Citation2009).

First, a focus on the ethnic group presumes a clear boundary between ‘ethnic’ and ‘mainstream’ economies. This is especially visible in literature that documents how migrants (or their children) manage to ‘break out’ to tap into non-ethnic markets, hence overcoming the barriers to growth of ‘staying in’ the ethnic economy (e.g. Basu Citation2011; Bouk, Vedder, and Poel Citation2013). The notion of ‘breaking out’ implies an either/or scenario, while it has been convincingly argued that immigrant entrepreneurs more typically engage in ‘intersective market activity’ when developing their business ventures (Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018, 458). As Smith and Stenning (Citation2006) argue with regard to formal and informal economies, we should see ‘ethnic’ and ‘mainstream’ economies not as idiosyncratic forms, but as interwoven sets of business interactions and associated practices, norms and values. Other critical scholars similarly point out that (migrant) entrepreneurs are known to challenge more than adhere to group boundaries (Pécoud Citation2010), and that the entrepreneur’s foremost domain – the marketplace – has always been a site for crossing cultural boundaries (Blanton Citation2015). The suggestion of these scholars, which we take to heart, is thus to be open to the likelihood that entrepreneurs are not confined to community boundaries, but often act as the ‘hybrids, the inbetweens’ (Nederveen Pieterse Citation2003, 46).

Second, as much as the boundary between the ethnic economy/community and wider society is overemphasized, so are internal ethnic community boundaries often underemphasized (Pécoud Citation2010; Ram, Jones, and Villares-Varela Citation2017; Romero and Valdez Citation2016). This is remarkable because it is shown that social differentiation within ethnic communities, for example along the lines of dialect or family loyalties (Verver and Koning Citation2018), access to transnational networks (Brzozowski, Cucculelli, and Surdej Citation2014), or in terms of class, gender or generation (Datta et al. Citation2007) affect entrepreneurship in manifold ways. Moreover, in many parts of the world there is increasing ‘diversity within diversity’ among migrants, which Vertovec (Citation2007) labels ‘super-diversity’. He urges scholars to better account for the concurrence of ethnicity and other variables, including migration status, spatial distribution, and labour market position. In all, any nuanced consideration of the interface of ethnicity and entrepreneurship among immigrants is attentive to the range of possible boundaries – ethnic and otherwise – within communities.

Third, and most fundamentally, taking ethnic group boundaries for granted is epistemologically dubious because to start from ‘the’ ethnic group implies the ‘premise that immigrants can be equated with ethnic groups’ (Rath Citation2000, 5). It reveals an implicit primordialist view (the idea that ethnic identity is based on fixed, primordial group attachments), whereas the opposing constructivist view (the idea that ethnic identities are socially constructed and thus dynamic) has become widely accepted among scholars (Brubaker Citation2009). In fact, it was Barth’s (Citation1969) Ethnic Groups and Boundaries that, in hindsight, marked the shift from primordialism to constructivism and hence revolutionized the study of ethnicity (Vermeulen and Govers Citation1994). In it, Barth critiques the ‘naïve assumption’ (Citation1969, 9) that ethnocultural boundaries persist through social isolation. This assumption, Barth laments, ‘has produced a world of separate peoples’ that, in the scholarly imagination, ‘can legitimately be isolated for description as an island to itself’ (Citation1969, 11). Notably, the issue is not a lack of awareness. Already in 1990 Aldrich and Waldinger called for a ‘more careful use of ethnic labels’ (131) in immigrant entrepreneurship studies, a call that has since been repeated by prominent scholars (Jones and Ram Citation2007; Nee, Sanders, and Sernau Citation1994; Rath and Kloosterman Citation2000). In analysing the role of ethnicity in immigrant entrepreneurship, we adhere to their dictum that ‘[e]thnic boundaries, as social constructions, are inherently fluid’ (Aldrich and Waldinger Citation1990, 132).

We are left with a conundrum about the relationship between ethnicity and entrepreneurship among immigrants. As Pécoud (Citation2000) explains, ‘it is nearly impossible to assign to ethnicity a dominant role in a debate while simultaneously deconstructing it’. In other words, the crucial question is how we can analyse the role of ethnic community membership in immigrant entrepreneurship without presuming – and thereby reifying – ethnic boundaries in the process. What is needed is a less reductionist approach, one that investigates rather than presumes the ‘ethnic nature’ of immigrant entrepreneurship (Verver and Koning Citation2018). In the remainder of this paper we argue that Barth’s work allows us to escape this conundrum. Barth shifts our analytic focus from the ethnic group towards micro-level immigrant entrepreneurial activities and, in extension, the ethnic boundaries where these activities unfold. The next section outlines the conceptual building blocks of a Barthian perspective on immigrant entrepreneurship.

3. Barth on entrepreneurship, spheres of value, and ethnic boundaries

Fredrik Barth’s work is well known in the social sciences broadly (Eriksen Citation2015), and is occasionally employed in entrepreneurship studies to reveal the embeddedness of entrepreneurs in community contexts (e.g. Fadahunsi and Rosa Citation2002; Mckeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015; Stewart Citation1990). In studies on immigrant entrepreneurship, however, Barth’s work is seldom used beyond passing reference (e.g. Dana and Morris Citation2007; Heberer Citation2005; Nee, Sanders, and Sernau Citation1994; Koning and Verver Citation2013; Peters Citation2002). Below, we present Barth’s work on entrepreneurship (Citation1963), spheres of value (Citation[1967] 2000) and ethnic boundaries (Citation1969).

Barth (Citation1963) is interested in the interrelation of entrepreneurial activity and the sociocultural life of the community. In relation to other members of the community, Barth attributes the entrepreneur a ‘more single-minded concentration’ on profit maximization and a ‘greater willingness to take risk’ (Citation1963, 8). The predicament of the entrepreneur, then, is to weigh monetary, material and immaterial profits against the costs of repudiating social barriers or commitments, including moral or legal condemnation within the community (cf. Stewart Citation2003). Barth (Citation1963) thus emphasizes their role as change agents who are embedded in and committed to their community, but who also upset and possibly transform their community in the pursuit of value creation (Dana and Morris Citation2007; Essers and Benschop Citation2009; Mckeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015).

Central to Barth’s work is the notion that entrepreneurs transfer across different ‘spheres for the exchange of value’ (Citation1963, 11). The concept of sphere denotes a system of circulation in a community, or ‘flow pattern’ (Barth Citation[1967] 2000, 152), within which goods and services attain a particular value in accordance with their uses and functions. Value thus has a double connotation: a monetary value of particular goods and services as well as moral values upheld within a particular community that constrain the development, sale or purchase of these goods and services. Possible ‘discrepancies of evaluation’ of goods and services may exist between spheres, and so entrepreneurial opportunity arises in the economic exploitation of these discrepancies (Barth Citation[1967] 2000, 158). Entrepreneurial resources and profits may belong in the same sphere, but the ‘essence of entrepreneurial activity’, according to Barth (Citation1963), is to discover new channels between spheres and exploit them (cf. Fadahunsi and Rosa Citation2002), even if this creates tension within the community. It follows that in pluralistic societies, where cultural groups with unlike spheres of value co-exist, entrepreneurial activity entails the establishment of ‘brokerage niches’ (Salisbury Citation1973, 91) and ‘mediating boundary transfers’ (Dana and Morris Citation2007, 809) between these groups.

As much as Barth explains the process of entrepreneurship in terms of boundary crossing, so does he address the socially constructed nature of ethnic boundaries. In an oft-quoted phrase, Barth states that the critical focus must be ‘the ethnic boundary that defines the group, not the cultural stuff that it encloses’ (Citation1969, 15, emphasis in original). As is implied in his notion of spheres, Barth does not deny the ‘culture-bearing aspect’ (12) of ethnic communities, including signals, signs, morals and value orientations. Yet, whether ethnic categories matter in everyday life, so he argues, depends on the maintenance of ethnic boundaries in interaction, and so we should focus on what is ‘organizationally relevant’ more than the ‘cultural contents’ per se (14).

In sum, Barth theorizes that (1) entrepreneurship is a balancing act between individual profit making and social-moral considerations within the community; (2) in pluralistic societies, where ethnic communities with unlike spheres of value co-exist, entrepreneurial opportunity arises in economic exchanges across these spheres; (3) entrepreneurship is thus found at the boundaries between ethnic communities. In the remainder of this paper we draw on the case of the Mennonites in Belize to examine how entrepreneurship occurs at ethnic boundaries.

4. Research context: Mennonites in Belize

Based on Barth’s work, we expect that, in order to create value, entrepreneurs must draw on different spheres of value that more or less parallel different communities. Therefore, we draw on an extreme case (Pratt Citation2008) where this is both unlikely to occur and clearly observable if it does occur: Mennonite entrepreneurs in Belize. As we outline below, Mennonite communities strive towards seclusion for religious reasons and consequently often live in geographically isolated places where they maintain their own way of life.

Mennonites are an Anabaptist movement that inherits its name from the influential Dutch religious leader and prolific writer Menno Simons. In the 16th century, Anabaptists branched off the radical reformation spreading through Northern Europe, rebelling, amongst others, against the practice of infant baptism. Mennonites’ religious zeal and their refusal to be absorbed in state administrative, military and educational institutions led to widespread persecutions and migration of Mennonite groups to more tolerant places in Europe and North America, and ultimately via Mexico to Belize in 1958 (Kraybill Citation2010).

A multi-ethnic society, Belize features the presence of ethnicities such as Maya, Chinese, Garifuna, East Indian, Creole, and Mestizo, of which the latter constitutes a narrow majority. Of a total population of around 320,000 people, about 12,000 are Mennonites. The Mennonite presence in Belize is characterized by a continuous tension between modernity and Mennonites’ strict religious-moral code. Mennonites believe in ‘separation from the world’ and hence reject ‘worldliness’, which conveys a sense of impurity and lack of moral standing, enticed by the seductions and luxuries of the outside world, including modern technologies (Loewen Citation1993). Internal debates about worldliness erupt with some regularity in Mennonite communities, as their members find themselves needing to adjust to changing times while attempting to adhere to the timeless interpretation of the Scripture referred to as Ordnung. Ordnung – translated as regulation, or discipline – summarizes the behavioural expectations of the local church body on topics such as fashionable clothing, gambling, taking photographs, technology use, participation in the wider society, and more broadly in expressing values like obedience, humility, and simplicity (Roessingh and Bovenberg Citation2016; Kraybill Citation2010).

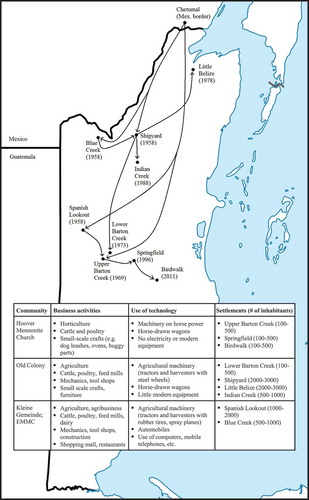

Mennonites are organized in communities that are united by their religious-moral code, which is strictly enforced in some and more loosely interpreted in other communities. Thus, Mennonite communities give varying appearances of technological and social pre-modernity, ranging from the use of airplanes to horse and buggy (Kraybill Citation2010; RoessinghCitation2007, Citation2013; Roessingh and Smits Citation2010). Different Mennonite settlements have spread across Belize under the rule of diverse community churches. Religiously inspired schisms in communities as well as land shortage triggers the creation of new settlements over time. The result of this dynamic is illustrated in .

5. Research methodology: ethnography

We employed ethnographic methodology to study entrepreneurial activities in different Mennonite communities in Belize. The promise of ethnography is increasingly recognized in entrepreneurship studies (Greenman Citation2011; Jack and Anderson Citation2002; Newth Citation2018; Watson Citation2013). Although ethnography inheres limitations in terms of generalizability to wider populations or contexts, it is well suited to capture the ways in which micro-level behaviour – including entrepreneurial behaviour – is embedded in context (Greenman Citation2013). As such, we investigate everyday business conduct as embedded in Mennonites communities and Belizean society, or, as Barth puts it, we are interested in the ‘chain of interactions between the entrepreneur and his environment’ (Citation1963, 7).

Ethnographic fieldwork was conducted by the second author as well as multiple master’s students and consisted of several periods of both multi-sited and single-sited fieldwork. Between 2002 and 2018, the second author visited Belize eleven times (totalling 38 weeks) travelling between different Mennonite settlements to converse and build relationships with entrepreneurs and other community insiders. Through his connections, thirteen master’s students have conducted fieldwork (around three months each) in different settlements, participating and gathering in-depth data of communal and business life. The four settlements in our sample include Blue Creek, Spanish Lookout, Shipyard and Springfield. As such, while our data is not exhaustive, it includes entrepreneurial activities taking place inside and between different communities spanning conservative to progressive orientations (see for the fieldwork periods in each settlement).

Table 1. Cases of Mennonite entrepreneurship

During fieldwork, the empirical focus was on the position of the Mennonites in Belize, evolving communal issues, (shifting) religious norms and values, business conduct, business-life histories, entrepreneurial networks, and dealings with technology and modernity. The researchers used observations and informal conversations, triggered by daily encounters as well as more planned visits, to tease out peoples’ experiences pertaining to these themes. By combining conversational and observational methods, both meaning making and behaviour were captured, enabling more complete interpretations (cf. Greenman Citation2011, Citation2013). Notes were sometimes jotted down during engagements, but more typically written up as soon as possible afterwards. Due to the nature of the research setting, formal interviews were rarely an option, while the use of a voice recorder was out of the question altogether. Our data thus consists of a collection of descriptive accounts and fieldnotes of conversations and observations, including literal quotations of research participants.

In line with ethnographic methodology (e.g. Greenman Citation2011; McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014), in the data analysis we moved iteratively between research participants’ accounts as reflected in the data, our interpretations thereof, and theoretical insights to synthesize these. The analysis consisted of an exploratory and a more systematic phase (cf. Miles and Huberman Citation1994). The former entailed a ‘speculative project in which observations are explored, hunches occur [and] perspectives are considered’ (Locke Citation2011, 630). With the three authors we independently reviewed and analysed the descriptive data. Going back and forth between individual analyses and joint discussions on our findings, we gradually came to realize that ethnic boundaries were centre-stage: entrepreneurs tended to challenge the religious-moral code of their communities and/or engage with people (Mennonites or other Belizeans) outside their communities when engaging in entrepreneurial activities. Extant literature on immigrant entrepreneurship did not provide us enough conceptual tools to explain the role of ethnic boundaries in entrepreneurship. Familiar with his Ethnic Groups and Boundaries (Citation1969), we began exploring Barth’s work and, from there, the idea that immigrant entrepreneurship unfolds at ethnic boundaries.

In the more systematic analysis phase, by way of ‘sifting through all data’ (Mckeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015, 54), we first selected 25 Mennonite businesses across the four settlements (see ). We drew together all empirical material related to the 25 businesses, totalling roughly 150 pages of written out descriptions (by master’s students) and 250 pages of fieldnotes (by the second author). For each business, we zoomed in on entrepreneurial activities throughout the biography of the business owner(s), and considered the boundary dynamics involved. Through constant comparison within and across businesses (cf. McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014), boundary dynamics surfaced that re-emerged in the data. Through this process, we ultimately arrived at three boundary dynamics: bridging, stretching and allying. In the ensuing section we describe these three boundary dynamics that are at the heart of a Barthian perspective to immigrant entrepreneurship.

6. Findings: boundary dynamics in Mennonite entrepreneurship in Belize

In line with Barth’s work, in the following three subsections we will consider how entrepreneurial activities generate three boundary dynamics within and across spheres of value at the levels of host society, ethnic community and multiple sub-communities. In doing so, we will consider both the leverage and limits for Mennonite entrepreneurs to engage in ethnic boundary dynamics, and hence we include examples not only of where Mennonites succeed, but also where they fail to create entrepreneurial ventures. To make transparent how our argument emerges from the data (cf. Greenman Citation2011; Mckeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015), we present an empirical table that outlines the three boundaries dynamics for each of the 25 businesses (). In the three sub-sections we present ‘vignettes’ – each of which is ‘a basic representation of an event and can involve individuals, behaviors, or contexts’ (Gioia and Poole Citation1984, 451) – of a selection of these 25 businesses.

Table 2. Ethnic boundary dynamics in Mennonite entrepreneurship

6.1. Bridging the boundary between Mennonite ethnicity and Belizean society

Even though Mennonites strive towards a life of seclusion, their interaction with Belizean society is crucial in Mennonites’ entrepreneurial activities. Even more so, this interaction was part of an agreement between early settlers and authorities that was made in 1958 and continues to this day. In exchange for autonomy in communal organization and the possibility to buy land, the Mennonites were expected play a key role in providing mostly basic necessities. ‘Farming is in our genes’ is an often-used phrase among Mennonites. They thus resorted to re-establish agricultural niches that they had occupied in other countries, including diary and meat production, and the cultivation of cash crops such as rice, fruits and vegetables (Penner, Reimer, and Reimer Citation2008; RoessinghCitation2007). However, this reciprocal relationship is shaped in more complex ways when we zoom in on the historical development of the interactions and interdependencies between different Mennonite communities and the Belizean society and state. Below, we illustrate this relationship with contrasting entrepreneurial trajectories in the settlements of Spanish Lookout and Springfield.

An exemplary business showing how Mennonites simultaneously draw on intra-ethnic resources and ties to other members of Belizean society is Cayo Dairies in the settlement of Spanish Lookout. Cayo Dairies was developed by a group of Mennonites seeking settlement coming in from Mexico in 1958. After negotiating the terms for their settlement with the local Belizean authorities, the Mennonites got in touch with a landowner whose land appeared to be fertile and bought her land. However, the group of Mennonites found themselves wholly unprepared for the challenging conditions, as one of the early settlers describes:

It was a time of hardship. The whole area [of Spanish Lookout] was one dense forest, nothing like we were used to in Mexico. The first years we mostly spent clearing the land. We cut trees with the locals [Mestizos they hired] and we worked at the sawmill. At night we couldn’t sleep because of the mosquitos, and we sometimes got lost in the bush. I still look around sometimes and realise that the cornfield, the gas station, the parts shop … it used to be all bush.

Attempting to breed cattle, they found that the animals that they had brought from Mexico were dying: ‘When we asked, the locals told us it was because of screw worms in sores.’ Indeed, the early settlers were forced to seek advice and help from local Belizeans to improve their livestock and make a living from the land.

Once the group had established itself in Spanish Lookout and milk production was successful, some members decided to start producing cheese from their overproduction. Initial efforts failed due to insufficient quantities of milk, and so the Cayo Dairies business was set up by a group of sixteen farmers, who together produced enough milk to also make cheese. Collectively, they built two wooden buildings for production and invested in expensive equipment imported from Pennsylvania, USA, needed to pasteurize and bottle the milk. From the outset, the company shipped its milk across Belize, starting in 1967 to Belize City, and expanding to other districts since. The business enabled the board to re-invest profits in renewing their equipment, such as larger generators, which was necessary because Spanish Lookout was not connected to the Belizean electricity grid. Although cheese production was a variable success because ‘making good quality cheese in a tropical country is hard’, the business survived and since 1994 also produces other dairy products such as ice cream.

Cayo Dairies is exemplary of businesses in Spanish Lookout, which has become a relatively wealthy place that caters to Mennonites and other Belizeans alike. Due to the Cayo Dairies ice cream store and other business like Chicken Walk, Brubaker Homebuilders, All Animal Feed Mill and Fehr Hatcheries that cater to wider Belizean society, Spanish Lookout acquired a reputation as one of the progressive Mennonite settlements. Many businesses employ both Mennonites as well as non-Mennonites. The Cayo Dairies ice cream store, while managed by Mennonites, is largely operated by non-Mennonite Belizean workers. Belizeans from nearby cities regularly travel to Spanish Lookout for shopping or to (look for) work. The road network is one of the best in Belize and regular busses travel to and from the settlement.

Whereas Spanish Lookout has thus become one of the more progressive Mennonite settlements, communities dominating other settlements have retained more conservative ways. Mennonites in more conservative communities often only speak Plautdietsch (Low German), while in Spanish Lookout people also speak English and Belizean Spanish to communicate with the outside world (SIB Citation2010). In addition, in more conservative communities the Ordnung is more strictly enforced by the Älteste (eldest) and Prediger (preachers); ordained leaders who often provide the central authority.

Mennonites in Springfield for example, a conservative settlement that is dominated by the Hoover Mennonite Church, take pride in living ‘a pure life, without electricity, without computers’, as an inhabitant explains. They denounce the ‘worldly’ behaviour of people in Spanish Lookout: ‘Sure, you will see us catching a bus when absolutely necessary, but you will not see us driving a car. Owning a car is part of man’s vanity. They should know better.’ In Springfield most settlers perform subsistence farming only and prefer not to interact at all with Belizean society. However, we observe how even a very conservative community like Springfield develops a degree of interaction with outsiders when they engage in entrepreneurial activity. The isolationist stance was challenged for example because families ran out of farmland over time, which meant that the community needed money to buy more farmland from the Belizean government. Father Schwartz, whose family sells trees, explains:

It’s a tradition in our family to grow trees. First someone had to bring the trees to Belmopan to sell them for us there, but now we can also sell to outsiders who come here. Thanks to the profit we could buy more land for our children. We bought land in Birdwalk [a nearby settlement] and Roseville [a new settlement in southern Belize]. The same is now happening with vegetables; some families now sell them in the market place so they can buy new land.

Thus, while Springfield is conservative, those members of the community who engage in entrepreneurial activity do have controlled interaction with the wider Belizean society. Another example thereof, already touched upon by father Schwartz, is a biweekly market place inside the settlement that is open to visitors. While the community leadership had initially been against economic activities that brought outsiders into the settlement, they eventually conceded to farmers’ appeals. Members of the progressive Kleine Gemeide community in Spanish Lookout, in contrast, have outposts in the cities of Belmopan, San Ignacio and Belize City to sell their goods there, something that would be unimaginable in the case of the conservative Hoover Mennonites of Springfield. Nevertheless, even in the progressive Kleine Gemeinde community, they employ a rotating schedule between families occupying the outpost, so as to protect them against ‘worldliness’.

These examples show that, on the one hand, Mennonite communities rely on strong internal solidarity that allows them pool financial and material resources necessary for entrepreneurship. As a Mestizo from Belmopan argues: ‘They are smart people who work together well. Look at the [horse-operated] sawmill [in Springfield]; they built the mill and bought the horses with the whole village. Everyone can use it’. While building on a Mennonite repertoire to set up businesses, the examples on the other hand show that, even in the most conservative communities, business innovation begets interactions with other Belizeans. Mennonites create profit, individually or collectively, by bridging spheres of value defined by their own communal order and the wider society and market, respectively. In the next section we will zoom in on what largely remained implicit in the above; the ways by which entrepreneurs negotiate exceptions to the constraints posed by the religious-moral code of their communities, and thus grow their businesses.

6.2. Stretching Mennonite communal boundaries

This paper commences with the example of Mr. Zimmerman, who finds himself excommunicated after unsuccessfully negotiating his business interest and the religious-moral code within the Old Colony community. In other cases, in contrast, entrepreneurs are successful in the negotiation, and thus stretch the boundaries of their ethnic communities’ interpretation of the religious-moral order. Below we describe the experiences of a butcher, Mr. Martin, and a chicken farmer, Mr. Hein, both members of the same community as Mr. Zimmerman’s original allegiance, and also residing in the settlement of Shipyard.

Mr. Martin buys up cattle from local farmers, processes the animals in a slaughterhouse, and transports the meat to a wide area, including places like San Ignacio, some 200 kilometres away. Mr. Martin uses a range of technologies for his business, while his community’s rules stipulate only minimal use of electricity and modern equipment. First, processing the meat requires electrically operated devices such as a chain to lift the carcases, a saw to divide the carcases in pieces, and refrigerators for storage. However, while electricity is available in Shipyard through generators, community members are not allowed to use these devices for 24 hours per day. Electricity is available 24 hours through the Belizean public network, but Mennonites are not allowed to tap into this source, because this would implicate them in ‘too worldly’ an arrangement. Second, to distribute the meat, Mr. Martin has to use a truck with regular rubber tires, which is forbidden within the community, as we saw in the case of Mr. Zimmerman. In time, however, Mr. Martin managed to circumnavigate these constraints to his business by negotiating minor, yet crucial exceptions to the rules. He managed to gain approval from the community Älteste and Prediger to use his generator for 24 hours, two times per week, which is what he needs to keep the meat frozen in the period between slaughtering the animals and distributing the meat. Mr. Martin relates: ‘I talked to the Church to ask if the community can approve. I had to ask because I cannot leave the meat in the heat. Luckily they approved’. Furthermore, he employs a Mestizo truck driver to transport the meat. Mr. Martin is allowed to accompany his truck driver and even to ride along, as long as he himself is not at the wheel.

A second example that demonstrates how entrepreneurship may test the boundaries of the religious-moral code is that of chicken farmer Mr. Hein. He breeds chickens and sells them to more progressive Mennonites in the settlement of Blue Creek, who are able to distribute the chicken meat further to cater to the Belizean market. The business went well and Mr. Hein decided to diversify into producing chicken feed. He built a feed mill with silos and included offices adjacent to the main building. Because of the Belizean heat, Mr. Hein installed air conditioning in the offices, which, unsurprisingly, given Mr. Martin’s experiences, angered the community Älteste and Prediger. According to Mr. Hein, ‘there are many people who have air conditioning here, but maybe only in their bedroom so others don’t see it’. Indeed, the Älteste and Prediger soon paid Mr. Hein a visit to tell him that he should be careful not to violate the Ordnung: he should not be using electrical equipment for more than a few hours per day. When he did violate this rule, however, he heard nothing more of it in the church, where the preacher would normally have followed up violations like these.

Mr. Hein has in fact long had a tenuous relation with the Älteste and Prediger. For example, he sometimes consumes alcohol and smokes, which is questionable in light of the communities’ Ordnung. He asked himself, somewhat rhetorically: ‘Should I let in the Church into my house?’ While Mr. Hein personally had come to doubt the Ordnung, he cannot publically express these doubts because the sales of his chicken feed – all of which is destined for the local Old Colony farmers – would plummet when he would be excommunicated. Hence, Mr. Hein has come to a sort of truce with the Älteste and Prediger: He keeps his doubts to himself and does not drink and smoke in public, while the Älteste and Prediger tolerate his excessive electricity use. Whereas in the case of Mr. Zimmerman in the introduction, the community boundary was transgressed, and in the case of Mr. Martin, the boundary shifted and a more liberal code was agreed upon, in the case of Mr. Hein the boundary is stretched and relations remain tense, as a new equilibrium is yet to be found.

Examples abound of entrepreneurs negotiating religious-moral codes, and hence re-articulating community boundaries. In some cases, boundaries are stretched. In the Kleine Gemeinde community in Spanish Lookout, for example, entrepreneurs early on negotiated the use of computers for business purposes, although the ban on personal use was maintained until recently. In Springfield, similarly, Hoover Mennonite entrepreneurs managed to negotiate a bi-weekly market within the settlement as we saw in the previous section. Among the progressive EMMC Mennonites, according to a businessman in Blue Creek, this process of stretching is so advanced that ‘the church has almost no influence on the way business is done anymore; business and church are growing apart’. In other cases, boundaries are maintained, adhering to the dictum that ‘we always have to be careful that the church doesn’t fall asleep’, as a preacher argues. For example, to date the Hoover Mennonites in Springfield refuse to have their cattle registered in an online registration system that was introduced by the government, thereby limiting their options to sell meat on the Belizean market.

This re-articulation of the boundaries at the micro level allows evolving Mennonite entrepreneurship, as it differentiates itself along the boundaries, through Mennonites’ interaction with outsiders, and with each other. Entrepreneurship drives the gradual opening up of rigid religious-moral code within ethnic communities, hence turning these communities increasingly progressive, which may render more conservative members dissatisfied. Micro-level immigrant entrepreneurial activities, then, also amount to a driving force that occasionally splits communities, sometimes leading to the establishment of new communities that attempt to reach back to the traditional roots of Anabaptism. In the next section we expand on the interdependencies between communities that have thus been created.

6.3. Allying across Mennonite communal boundaries

In this section we describe how entrepreneurs manage to create value by operating at the boundary between different Mennonite communities. The example of Happy Papaya Fruits, a papaya company in Blue Creek, shows how entrepreneurs make the most of the complementarity of resources that exist at each end of the boundary, and exploit the solidarity and trust that is found between Mennonites regardless of their differences.

Happy Papaya Fruits was founded when Mr. Wolfe, a Canadian Mennonite with family in Blue Creek, decided to survive the Canadian winters in Belize and connected to Mr. Horst, whose land appeared to have fertile soil for cultivating papayas. Both of them are members of the progressive Evangelical Mennonite Mission Church (EMMC) community, which originates in North America and thus provided them with connections to US investors for the papaya business. Their business mushroomed. Within a year, export volume to the US – arranged through their EMMC transnational network – grew from two to 25 containers per week. Using a Cessna airplane, they regularly flew back and forth between Blue Creek and the fields near Indian Creek to oversee the business.

Apart from fertile soil, one of the reasons they set up Happy Papaya Fruits on the land of Mr. Horst was the nearby settlement of Indian Creek, which they anticipated could offer them labourers. Indian Creek is an impoverished, Old Colony settlement that sprung off from land shortage in Shipyard. Younger couples had left Shipyard in search of land and tried to build a life in the new settlement. The settlers of Indian Creek, however, failed to live purely on subsistence farming because they lacked financial capital to purchase the necessary farming equipment. Hence they were forced to seek work outside of their own community, working for other Mennonites in slaughterhouses, feed mills, or on the rice fields. Indian Creek became known as a poor community where predominantly Low German is spoken, and which is dependent on other Mennonite communities to survive.

While Happy Papaya Fruits employed Old Colony Mennonites from the outset, the company gradually grew so large that it needed more workers than Indian Creek could provide. As Mr. Horst relates:

There are no more employees available in Indian Creek. Almost everyone is working for us, but we need more workers. We have received phone calls from San Felipe [a mestizo community] almost every day for the last few months, asking if they can work for us.

The growth of the company and the entrance of non-Mennonite employees, however, caused tensions between all the parties involved in the business. Within management – made up of both Blue Creek and English-speaking Indian Creek Mennonites – tensions arose over religious interpretations, where lower ranked Indian Creek Mennonites looked down on the higher ranked, but ‘more worldly’ Blue Creek EMMC Mennonites. Within the work force, Indian Creek Mennonites initially refused to work with non-Mennonites.

The example of Happy Papaya Fruits demonstrates the negotiation process between members of different Mennonite communities; in this case the EMMC owners and their Old Colony employees. On the one hand, the owners try to respect the Indian Creek workers’ moral-religious code, for example when they accommodate them with separate commuting busses for men and for women. Furthermore, they tolerate them to bring their 12-year old children to do packaging, which Mr. Horst claimed the Ministry of Education approved because ‘this job is less physical than working on the fields’. On the other hand, the Old Colony Mennonites eventually conceded to work with non-Mennonites.

Despite their differences, trust and solidarity is found between Mennonite communities, to their mutual economic benefit. This especially surfaces when Mr. Wolfe and Mr. Horst express their views on employing Indian Creek Mennonites versus mestizo Belizeans. Mr Horst argues that while native Belizeans commit to regular terms of employment and may not always prove to be a stable work force, Mennonites will do more and have better availability. Furthermore, while ‘you have to be on top of [non-Mennonite employees] all the time’, Mr. Horst found he could entrust Mennonites to work more autonomously and without written agreement. Thus, he sometimes put Mennonites in management positions even when there was a better-educated non-Mennonite candidate. In the words of another company manager; ‘we rather work with brothers than with others’.

Another arrangement that was set up by Happy Papaya Fruits similarly shows trust, solidarity, and mutual benefit amongst different Mennonite communities. Having developed the export of papayas, demand grew beyond what the company could deliver on its own. Simultaneously, rice farmers in Blue Creek as well as Indian Creek were looking for more profitable opportunities than growing rice. The company then helped them develop papaya plantations by providing credit for the start-up phase and by buying up and arranging the export of their papayas.

Happy Papaya Fruits illustrates the relationship between prosperous, progressive communities, where most entrepreneurship is found, and more conservative, often impoverished communities. The ethnicity of Mennonites as such is sometimes equivocal: on the one hand, the internal divisions are sometimes so extreme that conservatives regard progressives no longer as Mennonites on account of being ‘too worldly’. Vice versa, asked about Mennonite identity, a businessman from Blue Creek replies:

It depends. When I’m in the city being a Mennonite is not on my mind. […] When you look at Blue Creek, you don’t see any of the girls wearing a head cover these days, things will go the same way in Indian Creek. It just takes time. I hope they don’t lose their identity.

On the other hand, conservatives can still rely on shared Mennonite solidarity for jobs in neighbouring communities, as well as credit systems and other help that imply great levels of ethnic trust. The example of Happy Papaya Fruits shows that entrepreneurs ally across the boundaries between Mennonite communities; they reconcile the differences between them, build on mutual solidarity, and benefit from their complementary resources.

7. Discussion: towards a Barthian perspective on immigrant entrepreneurship

Based on our findings presented above, a clear pattern emerges in the relationship between ethnicity and entrepreneurship among Mennonites in Belize, which is congruent with Barth’s work (Citation1963, Citation1969; Citation[1967] 2000). Entrepreneurship among the Mennonites generates three distinct boundary dynamics. On the macro level, at the boundary between Mennonite ethnicity and Belizean society, entrepreneurs bridge value created within the communally defined sphere, based on internal Mennonite solidarity and the sharing of resources, and the more arm’s-length, market-based sphere for the exchange of value of the wider Belizean society. On the micro level, the boundaries of individual Mennonite communities are sometimes stretched, depending on whether, in attempts to develop legitimacy for their entrepreneurial ambitions, entrepreneurs fail or succeed to open up the religious-moral code that characterizes the communal sphere. On the meso level, at the boundaries between conservative and progressive Mennonite communities, entrepreneurship is found in allying the different religious-moral code existing between Mennonite spheres of value and securing complementary resources embedded in these different communities in the process. Taken together, Mennonite entrepreneurship is thus shaped by a poly-ethnic system spanning individual communities, Mennonite ethnicity at large, and Belizean society, and itself shapes this system by stretching, bridging and allying across the boundaries of communally defined spheres of value implied in this system.

Although developed in the context of the Mennonites in Belize, when stripped of its context-specific attributes a Barthian perspective can be applied to other contexts of immigrant entrepreneurship as well. It hypothesizes that entrepreneurship among migrants is found in (1) bridging the boundary between societal and ethnic spheres of value, (2) stretching the boundaries of ethnic spheres, and (3) allying across the boundaries of sub-ethnic spheres. In different communal and societal contexts, these three dimensions may manifest in different ways, as we explain below drawing on existing literature.

Bridging, firstly, occurs when (nascent) entrepreneurs spot and exploit an opportunity in the discrepancy between ethnic and other societal spheres of value. As for the Mennonites in Belize, this often means that entrepreneurs draw on intra-ethnic trust and reciprocity to pool resources (e.g. credit, labour, land, networks, knowledge) in developing particular goods or services, but subsequently cater to an ethnically more diverse customer base to sell these goods or services (e.g. Basu Citation2011; Drori and Lerner Citation2002). Studies in other context similarly highlight bridging activities; in South Africa, for example, immigrant entrepreneurs create value by integrating different value chains through ethnically diverse partnerships (Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018), while in Italy they do so by creating ethnically hybrid management teams (Arrighetti, Bolzani, and Lasagni Citation2014). In our interpretation, these studies reiterate our point that we need to recognize the intersections of ethnic and other societal or ethnic spheres as the sites where entrepreneurship often happens.

Stretching, secondly, entails the challenging of established norms, values, and practices within ethnic communities, which opens up space for entrepreneurship over time. Stretching pertains to religious-moral code in the case of the Mennonites in Belize, but will manifest differently elsewhere. Essers and Benschop for example find that Muslim women in the Netherlands ‘stretch the boundaries of what is allowed […] in order to resist traditional, dogmatic interpretations of Islam’ (Citation2009, 403). In yet other cases, stretching occurs where second-generation migrants challenge their parents’ ways. In the United Kingdom, for example, growth-oriented children of immigrants reach out to banks to finance their business, as such going against established practice among their more survival-oriented forebears, who prefer a sole reliance on family capital (Ram et al. Citation2003). However incrementally, efforts like these stretch the boundaries of ethnic spheres of value, which creates leverage for entrepreneurs to develop or introduce particular goods and services.

Allying, thirdly, occurs when entrepreneurs exploit discrepancies between sub-ethnic spheres of value within their wider ethnic sphere. Among the Mennonites in Belize, sub-ethnic spheres are comprised of communities of more progressive or conservative orientations. In other contexts, sub-ethnic spheres may be based on other forms of sociocultural differentiation within the broader ethnic sphere, such as age, class, gender, family background, or dialect group. In Cambodia, for example, entrepreneurs of Teochiu descent (a dialect group from south China) build on a Teochiu business culture and network to acquire credit or access to sectoral associations, while relying on business relationships with other (non-Teochiu) Chinese in the East Asian region for the supply of raw materials or machinery (Verver and Koning Citation2018). Typically, family groupings comprise sub-ethnic spheres; kinship solidarity within families is often crucial as a pool of start-up capital and a source of trustworthy and cheap labour (e.g. Karra, Tracey, and Phillips Citation2006). Different generations within migrant communities, lastly, also tend to comprise discrete spheres, and (family-based) entrepreneurship often involves allying older generation resources (e.g. capital, ethnic network) to younger generation resources (e.g. professional network and knowledge) (e.g. Koning and Verver Citation2013). Entrepreneurship tends to involve the application of ‘combinations of the resources at hand’ (Baker and Nelson Citation2005, 333), and sub-ethnic spheres are often complementary in assuring the necessary variety of resources.

A Barthian perspective heeds calls by critical scholars (Brubaker Citation2009; Danes et al. Citation2008; Pécoud Citation2000; Rath Citation2000) to move beyond the analytic focus on ethnic groups. First, it reveals that entrepreneurial activity is often found at the intersection of ‘ethnic’ and ‘mainstream’ economies, and hence moves away from either/or scenarios that do not reflect the complex embedding of immigrant entrepreneurship (Griffin-El and Olabisi Citation2018; Pécoud Citation2010). Second, a Barthian perspective uncovers the diverse ways by which internal differentiation within ethnic groups affects entrepreneurship, and thereby also echoes literature on intersectionality (Romero and Valdez Citation2016) and super-diversity (Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011) that similarly stresses the need to go beyond the false presumption of uniform ethnic communities in studying business life. Third, Barth’s work allows us to investigate the role of ethnicity in entrepreneurial activities while avoiding ‘groupism’ and primordialism, and thus attends to appeals for the more careful use of ethnic labels (Aldrich and Waldinger Citation1990; Rath and Kloosterman Citation2000). Barth’s notion of spheres is particularly instrumental here: it permits an investigation of the ways in which entrepreneurs enact a communally shaped social and symbolic order, but avoids an a priori conflation of immigrants and ethnic community.

In developing a Barthian perspective this paper makes two contributions, the first of which lies in a critical reappraisal of the role of ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship. While extant literature that explicates this role – the empirical studies and critical reviews outlined above – is fragmented (Pécoud Citation2010), we integrate insights from this literature and the work of Barth to develop a comprehensive framework for understanding ethnic boundary dynamics in immigrant entrepreneurship. Second, a Barthian perspective attends to calls for more micro-processual approaches to understanding the mixed embeddedness of immigrant entrepreneurship (Peters Citation2002; Storti Citation2014; Wang and Warn Citation2018) by highlighting the ‘dynamic interconnection between macro- and micro-phenomena’ (Barth Citation1981, 12). On the one hand, Barth’s work is consistent with the notion of mixed embeddedness because it suggests that immigrant entrepreneurship revolves around the dynamics between the entrepreneur, ethnic community networks and the wider society’s institutions and market. On the other hand, Barth urges us to shift the empirical focus from the ethnic group to entrepreneurial activity (cf. Jones and Ram Citation2007; Ma et al. Citation2013; Storti Citation2014) as a balancing act between the self-interested pursuit of profit and social-cultural legitimacy within the community.

Our Barthian perspective requires that we add two caveats. First, a limitation of our focus is that we have left out a consideration of immigrant entrepreneurship that does not happen at ethnic boundaries. Indeed, sometimes entrepreneurship is entirely confined to the ethnic community in terms of supply, demand, resources, labour, and etcetera, also among the Mennonites in Belize. While we acknowledge this, we also claim that the extent to which entrepreneurs are drawn towards ethnic boundaries, especially when they pursue innovative business activity, is grossly underestimated, and that this may in fact be the more typical pattern in immigrant entrepreneurship in most contexts. Second, critics argue that by positing ethnic boundaries, Barth also presupposes the existence of ethnic groups, thereby contributing, ‘against his own intentions, to the reification of groups’ (Brubaker Citation2009, 29). Barth himself admits that the image of boundaries may be ‘inappropriately absolute’ (Citation1963, 12). While this may be true, at the same time it is exactly by zooming in on the entrepreneurial activities that occur at these boundaries that we come to recognize them as fluid, not fixed, and porous, not impervious.

We suggest a few areas for further research. First, future studies may provide insight into possible manifestations, some of which we have pinpointed above, of the three boundary dynamics that we identify, and will have to establish whether – separately or in combination – these three dynamics explain entrepreneurial activity among immigrants in other contexts. Second, the analytic shift from the ethnic group to entrepreneurial activity broadens the focus from studying how ethnic identity enables and constrains entrepreneurship to how, vice versa, entrepreneurial activity also affects the construction of ethnic identity. After all, our findings reveal that ethnic boundaries and, in extension, ethnic identities are rendered dynamic as a result of entrepreneurs’ negotiations between profit-making and social-cultural legitimacy within and across communally defined spheres of value. Moving away from simplistic understandings of ethnic identity in terms of ‘more or less’ or ‘in or out’, this may be a vehicle to better capture the situational and multiform nature of ethnic identification (cf. Heberer Citation2005; Pécoud Citation2004).

Considering future research directions, lastly, whereas most immigrant entrepreneurship studies interpret entrepreneurship as synonymous with self-employment, Barth instead emphasizes innovation and risk-taking behaviour, mirroring a Schumpetarian understanding (Reichman Citation2013) that is more common in ‘mainstream’ entrepreneurship studies. As such, a Barthian perspective has the potential to generate cross-fertilization between immigrant and ‘mainstream’ entrepreneurship research. Calls for more cross-fertilization have been made in both fields: while ‘mainstream’ entrepreneurship studies are criticized for ignoring entrepreneurship (e.g. migrant or female entrepreneurship) that deviates from the ‘archetype of the white, male, individualistic, Calvinist entrepreneur’ (Essers and Benschop Citation2009, p. 420; cf. Vershinina and Rodgers Citation2019; Welter et al. Citation2017), vice versa, it is regretted that immigrant entrepreneurship studies tend to ‘retreat into the ghetto of special case ethnicity […] without reference either to “ethnic majority” entrepreneurs or to the scholarship these have engendered’ (Jones and Ram Citation2007, p. 440–441; cf. Rath Citation2000). Entrepreneurship literature has turned its attention to notions of entrepreneurial action (Watson Citation2013) and practice (Johannisson Citation2011), which may enrich the micro-level study of immigrant entrepreneurship.

8. Conclusion

In an attempt to contribute ‘renewed analytical tools’ (Pécoud Citation2010, 71) to immigrant entrepreneurship studies, in this paper we have developed a Barthian perspective. We have integrated insights from empirical studies on the micro-level ethnic dynamics of immigrant entrepreneurship, critical reviews of the field, and the work of Frederik Barth to arrive at a comprehensive framework for understanding the role of ethnic boundary dynamics. To develop this framework, we have drawn on the case of the Mennonites in Belize to identify three boundary dynamics that are generated by immigrant entrepreneurial activity: bridging the boundary between societal and ethnic spheres, stretching the boundaries of ethnic spheres, and allying across the boundaries between sub-ethnic spheres. A Barthian perspective explains the ways in which immigrant entrepreneurs create value in the tenuous, precarious dynamics that characterize ethnic boundaries.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. Pseudonyms are used for the names of individuals and businesses throughout this paper.

References

- Aldrich, H. E., and R. Waldinger. 1990. “Ethnicity and Entrepreneurship.” Annual Review of Sociology 16: 111–135. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.16.080190.000551.

- Aliaga-Isla, R., and A. Rialp. 2013. “Systematic Review of Immigrant Entrepreneurship Literature: Previous Findings and Ways Forward.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (9–10): 819–844. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.845694.

- Anderson, A. R. 2000. “Paradox in the Periphery: An Entrepreneurial Reconstruction?” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 12 (2): 91–109. doi:10.1080/089856200283027.

- Arrighetti, A., D. Bolzani, and A. Lasagni. 2014. “Beyond the Enclave? Break-outs into Mainstream Markets and Multicultural Hybridism in Ethnic Firms.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (9–10): 753–777. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.992374.

- Baker, T., and R. E. Nelson. 2005. “Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction through Entrepreneurial Bricolage.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (3): 329–366. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329.

- Barth, F. 1963. “Introduction.” In The Role of the Entrepreneur in Social Change in Northern Norway, edited by F. Barth, 5–18. Bergen: Norwegian Universities Press.

- Barth, F. 1969. “Introduction.” In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference, edited by F. Barth, 9–38. Illinois: Waveland Press.

- Barth, F. 1981. Process and Form in Social Life. Selected Essays of Fredrik Barth. Vol. I. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Barth, F. [1967] 2000. “Economic Spheres in Darfur.” In Entrepreneurship: The Social Science View, edited by R. Swedberg, 139–160. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Basu, A. 2011. “From “Break Out” to “Breakthrough”: Successful Market Strategies of Immigrant Entrepreneurs in the UK.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship 15: 1–23.

- Blanton, R. E. 2015. “Theories of Ethnicity and the Dynamics of Ethnic Change in Multiethnic Societies.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (30): 9176–9181. doi:10.1073/pnas.1421406112.

- Bouk, F. E., P. Vedder, and Y. T. Poel. 2013. “The Networking Behavior of Moroccan and Turkish Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Two Dutch Neighborhoods: The Role of Ethnic Density.” Ethnicities 13 (6): 771–794. doi:10.1177/1468796812471131.

- Brubaker, R. 2009. “Ethnicity, Race, and Nationalism.” Annual Review of Sociology 35 (1): 21–42. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115916.

- Brzozowski, J., M. Cucculelli, and A. Surdej. 2014. “Transnational Ties and Performance of Immigrant Entrepreneurs: The Role of Home-country Conditions.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (7–8): 546–573. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.959068.

- Dana, L. P., and M. Morris. 2007. “Towards A Synthesis: A Model of Immigrant and Ethnic Entrepreneurship.” In Handbook of Research on Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship: A Co-evolutionary View on Resource Management, edited by L. P. Dana, 803–811. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Danes, S. M., J. Lee, K. Stafford, and R. K. Z. Heck. 2008. “The Effects of Ethnicity, Families and Culture on Entrepreneurial Experience: An Extension of Sustainable Family Business Theory.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 13 (3): 229–268. doi:10.1142/S1084946708001010.

- Datta, K., C. McIlwaine, Y. Evans, J. Herbert, J. May, and J. Wills. 2007. “From Coping Strategies to Tactics: London’s Low-pay Economy and Migrant Labour.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 45 (2): 404–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8543.2007.00620.x.

- Dheer, R. 2018. “Entrepreneurship by Immigrants: A Review of Existing Literature and Directions for Future Research.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 14 (3): 555–614. doi:10.1007/s11365-018-0506-7.

- Drori, I., and M. Lerner. 2002. “The Dynamics of Limited Breaking Out: The Case of the Arab Manufacturing Businesses in Israel.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 14 (2): 135–154. doi:10.1080/08985620110112619.

- Eraydin, A., T. Tasan-kok, and J. Vranken. 2010. “Diversity Matters: Immigrant Entrepreneurship and Contribution of Different Forms of Social Integration in Economic Performance of Cities.” European Planning Studies 18 (4): 521–543. doi:10.1080/09654311003593556.

- Eriksen, T. H. 2015. Fredrik Barth: An Intellectual Biography. Bergen: Pluto Press.

- Essers, C., and Y. Benschop. 2009. “Muslim Businesswomen Doing Boundary Work: The Negotiation of Islam, Gender and Ethnicity within Entrepreneurial Contexts.” Human Relations 62 (3): 403–423. doi:10.1177/0018726708101042.

- Fadahunsi, A., and P. Rosa. 2002. “Entrepreneurship and Illegality.” Journal of Business Venturing 17 (5): 397–429. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00073-8.

- Fairchild, G. B. 2010. “Intergenerational Ethnic Enclave Influences on the Likelihood of Being Self-Employed.” Journal of Business Venturing 25 (3): 290–304. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.10.003.

- Gioia, D. A., and P. P. Poole. 1984. “Scripts in Organizational Behavior.” Academy of Management Review 9 (3): 449–459. doi:10.5465/amr.1984.4279675.

- Greenman, A. 2011. “Entrepreneurial Activities and Occupational Boundary Work during Venture Creation and Development in the Cultural Industries.” International Small Business Journal 30 (2): 115–137. doi:10.1177/0266242611431093.

- Greenman, A. 2013. ““Everyday Entrepreneurial Action and Cultural Embeddedness: An Institutional Logics Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (7–8): 631–653. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.829873.

- Griffin-El, E. W., and J. Olabisi. 2018. “Breaking Boundaries: Exploring the Process of Intersective Market Activity of Immigrant Entrepreneurship in the Context of High Economic Inequality.” Journal of Management Studies 55 (3): 457–485. doi:10.1111/joms.12327.

- Heberer, T. 2005. “Ethnic Entrepreneurship and Ethnic Identity: A Case Study among the Liangshan Yi(Nuosu) in China.” China Quarterly 182: 407–427. doi:10.1017/S0305741005000251.

- Jack, S. L., and A. R. Anderson. 2002. “The Effects of Embeddedness on the Entrepreneurial Process.” Journal of Business Venturing 17 (5): 467–487. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3.

- Johannisson, B. 2011. “Towards a Practice Theory of Entrepreneuring.” Small Business Economics 36 (2): 135–150. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9212-8.

- Jones, T., and M. Ram. 2007. “Re-embedding the Ethnic Business Agenda.” Work, Employment & Society 21 (3): 439–457. doi:10.1177/0950017007080007.

- Karra, N., P. Tracey, and N. Phillips. 2006. “Altruism and Agency in the Family Firm: Exploring the Role of Family, Kinship, and Ethnicity.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30: 861–878. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00157.x.

- Kloosterman, R., and J. Rath. 2001. “Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Advanced Economies: Mixed Embeddedness Further Explored.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (2): 189–201. doi:10.1080/13691830020041561.

- Kloosterman, R., J. P. van der Leun, and J. Rath. 1999. “Mixed Embeddedness: (In)formal Economic Activities and Immigrant Businesses in the Netherlands.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 23 (2): 252–266. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00194.

- Koning, J., and M. Verver. 2013. “Historicizing the ‘Ethnic’ in Ethnic Entrepreneurship: The Case of the Chinese in Bangkok.”Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (5/6): 325-348. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.729090.

- Kraybill, D. B. 2010. Concise Encyclopedia of Amish, Brethen, Hutteries, and Mennonites. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Locke, K. 2011. “Field Research Practice in Management and Organization Studies: Reclaiming Its Tradition of Discovery.” Academy of Management Annals 5 (1): 37–41. doi:10.5465/19416520.2011.593319.

- Loewen, R. 1993. Family, Church and Market: A Mennonite Community in the Old and the New Worlds, 1850-1930. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Ma, Z., S. Zhao, T. Wang, and Y. Lee. 2013. “An Overview of Contemporary Ethnic Entrepreneurship Studies: Themes and Relationships.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 19 (1): 32–52. doi:10.1108/13552551311299242.

- McKeever, E., A. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2014. “Entrepreneurship and Mutuality: Social Capital in Processes and Practices.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (5–6): 453–477. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.939536.

- Mckeever, E., S. Jack, and A. Anderson. 2015. “Embedded Entrepreneurship in the Creative Re-construction of Place.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (1): 50–65. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.002.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Nazareno, J., M. Zhou, and T. You. 2019. “Global Dynamics of Immigrant Entrepreneurship: Changing Trends, Ethnonational Variations, and Reconceptualizations.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research 25 (5): 780–800. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-03-2018-0141.

- Nederveen Pieterse, J. 2003. “Social Capital and Migration: Beyond Ethnic Economies.” Ethnicities 3 (1): 29–58. doi:10.1177/1468796803003001785.

- Nee, V., J. M. Sanders, and S. Sernau. 1994. “Job Transitions in an Immigrant Metropolis: Ethnic Boundaries and the Mixed Economy.” American Sociological Review 59 (6): 849–872. doi:10.2307/2096372.

- Newth, J. 2018. “Hands-on” Vs “Arm’s Length” Entrepreneurship Research. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research. Advance online publication. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-09-2016-0315.

- Pécoud, A. 2000. “Thinking and Rethinking Ethnic Economies.” Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies 9 (3): 439–462. doi:10.1353/dsp.2000.0018.

- Pécoud, A. 2004. “Entrepreneurship and Identity: Cosmopolitanism and Cultural Competencies among German-Turkish Businesspeople in Berlin.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1080/1369183032000170141.

- Pécoud, A. 2010. “What Is Ethnic in an Ethnic Economy?” International Review of Sociology 20 (1): 59–76. doi:10.1080/03906700903525677.

- Penner, H. R., J. D. Reimer, and L. M. Reimer. 2008. Spanish Lookout since 1958: Progress in Action. Benque Viejo: BRC Printing.

- Peters, N. 2002. “Mixed Embeddedness: Does It Really Explain Immigrant Enterprise in Western Australia (WA)?” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 8 (1/2): 32–53. doi:10.1108/13552550210423705.

- Portes, A., and J. Sensenbrenner. 1993. “Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action.” American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1320–1350. doi:10.1086/230191.

- Pratt, M. 2008. “Fitting Oval Pegs into Round Holes.” Organizational Research Methods 11 (3): 481–509. doi:10.1177/1094428107303349.

- Ram, M., T. Jones, and M. Villares-Varela. 2017. “Migrant Entrepreneurship: Reflections on Research and Practice.” International Small Business Journal 35 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1177/0266242616678051.

- Ram, M., D. Smallbone, D. Deakins, and T. Jones. 2003. “Banking on “Break-out”: Finance and the Development of Ethnic Minority Businesses.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 29 (4): 663–681. doi:10.1080/1369183032000123440.