ABSTRACT

There is a re-positioning of entrepreneurship towards the sustaining, the frugal, the local, and the everyday. This poses challenges for peripheral policy work, especially around growth, at sectoral and regional levels. Through collaborative workshops with engaged craft brewing stakeholders, this study generated deep new insights into how diverse forms of value can come to be created, shared, stewarded, invested in, grown, given away, and held as a collective resource, in order to both sustain community, and build sectoral growth. As such, we highlight novel entrepreneurial practices and capitals which, taken together, can respond both to critical chorus demands for an urgent repositioning towards frugal sustaining folk enterprise, and yet also retain a strong sense of peripheral socio-economic progress implied by the growth agenda, and its policies.

Introduction

In the face of multiple recent crises, entrepreneurship’s radical ‘critical chorus’ has converged in a direction of travel towards the local, the collaborative, the communitarian, the sustaining, and the replenishing of depleted peripheral places (Tedmanson et al. Citation2012; see also Drakopoulou Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021; Ramoglou, Gartner, and Tsang Citation2020; Fayolle et al. Citation2018; Welter and Baker Citation2020). It asks us to explore other ways of doing entrepreneurship – of being entrepreneurial – at the edges, to ‘replace the heroism of high consumption for high growth with a folk hero of frugal production’ (Drakopoulou Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021, 12).

Entrepreneurship has also recently been challenged to take a much wider view of the value enacted by the socio-economic change-makers whom we study (Drakopoulou Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021). Particular challenges have been laid against the extreme dangers of considering only the economic, innovation, and jobs creation value created by high-growth firms. Audretsch and Moog (Citation2020) argue that entrepreneurship, in the aggregate – at a regional level, say – is essentially a tool by which society solves specific pressing contemporary problems.

What is entrepreneurship for, in today’s context of multi-faceted crisis? Especially, what is entrepreneurship’s role in sustainable and sustaining regional development? Can growth ever be sustaining, and embrace wider understandings of value? Is sustaining growth achievable or must we choose to address one problem over the other, at regional, sectoral and local policy planning levels? Our study aims to address the interlinked research questions that underlie the crafting of sustainable growth, namely: If we are to pursue ‘sustainable and sustaining growth’ – if this is what entrepreneurship is for at a regional level – what might that look like, how might it evolve, what kinds of value does it create, and which practices does it enact in their pursuit?

To address this aim, we selected the artisanal brewing sector for a number of reasons, but dominant amongst these was their combination of presenting internationally as a high-growth sector, with an artisanal folk ethos that is almost archetypal, showing a very strong focus on community, knowledge and resource sharing, and sustaining local place, whilst building thriving global networks (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018). There are additional structural rationales which make this sector such a promising natural laboratory for solving our puzzle. Our empirical setting, the European craft beer sector, had experienced very high growth levels in recent years, and a constant influx of new, small, specialist entrepreneurial ventures seeking to serve customers wishing to disassociate from the mass-produced, undifferentiated beer offerings of the large, generalist breweries (Elzinga, Tremblay, and Tremblay Citation2015; Argent Citation2017; Cabras and Bamforth Citation2016; Carroll and Swaminathan Citation2000).

Craft brewing also offers diverse and complex affordances as a place-based regional policy tool. The sector has become the focus of significant recent policy consideration, and appears to offer complex, and perhaps not directly economic, benefits to regional development (Ellis and Bosworth Citation2015). As with other food and drink and craft sectors, batch production of higher quality goods – with their branding grounded in locality, heritage and place – offers opportunities for smaller communities to capture some of these potential benefits, through local production. Building and embedding supply chains into regional economies, cluster policies and other ways to retain more value added within the area by raising the local content in manufactured goods, and so local multiplier effects, contrasts with traditional export-based assembly branch plants. These arguments and promises have been illustrated in policies and strategies (e.g., Scottish Government Citation2019; Welsh Government Citation2014) and in previous research (Argent Citation2017; Barth et al. Citation2015; Burnett and Danson Citation2004; Muñoz and Kimmitt Citation2019; Snihur Citation2016; Leitch and Harrison Citation2016; Whittam and Danson Citation2001).

Our paper thus explores how an innovative, high-growth, and collaborative food and drink sector – craft beer – organizes and establishes its growth, whilst maintaining and building its ‘everyday entrepreneurship’ ethos. We focused on uncovering the values the sector seeks to create and curate, as well as the practices, problems and potentialities it encounters and enacts in so doing. To achieve this, the paper embraces a distinctive integrated approach. First, we draw from Bourdieu’s (Citation1986) capital theory to examine how diverse entrepreneurial capitals intertwine in order to allow the sector to organize itself and its resources, legitimize its presence, and create a future for itself. Bourdieu’s (Citation1977, Citation1984, Citation1986) theory of practice, has increasingly been adopted in management and organization theory scholarship (Gomez and Bouty Citation2011), and has been proposed as potentially valuable for examining symbolic struggles for legitimization of emergent craft (and creative) industries (Jones et al. Citation2016; Pret, Shaw, and Drakopoulou Dodd Citation2016).

Next, we approach the investigation empirically via a participatory research study with a participant pool of multiple stakeholders from the contemporary European craft beer sector. The study explicitly adopts what might be termed an epistemology of everyday entrepreneurship, striving to enact, reflexively, the communitarian and inclusive practices we seek to study. Our methodologies were developed to manifest these principles, and, we hope, make a novel contribution in their own right to emerging issues around emerging and sustaining locally embedded cultural assets, wisdoms, competences and perspectives. More than this, previous research has shown craft brewers to be highly skilled in innovation, collaboration, creativity, meaning making, craft entrepreneurship, and the co-creation of cultural capital (see, for example, Wilson et al. Citation2018). They are our peers, if not our betters, in enacting such practices, and we can learn much by engaging fully with craft practitioners throughout a study’s journey. Including participants in all our own processes was thus not only a more democratic and embedded approach, it also, in this case especially, significantly added to the knowledge and skills brought to the research.

The European craft beer sector

The European craft brewing sector presents an ideal context to explore sustainable growth models, as it makes such a valuable potential archetype of a growing, sustaining artisanal community, and, thus a highly promising regional pivot organization, for various reasons.

Europe is the world’s second-largest producer of beer, after China, and a recent report highlighted widespread growth in the opening of new craft breweries, with ‘particularly striking increases in numbers in the Czech Republic, France, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland’ (Europe Economics Citation2016, 13). Embodying characteristics of craft and localness and both drawing on and precipitating social, cultural and economic changes, their approach has been argued to revolutionize the beer market (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018; Garavaglia Citation2020). Within the sector there has been a lack of focus on growth per se, rather as a supporter of small-scale, locally owned businesses (Reid Citation2018) and the emergence of hybrid business models balancing commerce and craft (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018). This focus on authenticity and small-scale craft specialists is in stark contrast to mainstream beer production (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018; Clemons, Gao, and Hitt Citation2006; Elzinga, Tremblay, and Tremblay Citation2015; Carroll and Swaminathan Citation2000; Carroll Citation1985; Argent Citation2017; Cabras and Bamforth Citation2016).

Crafting is a combination of production skills of the brewers with the materiality of ingredients, and local identity, ‘a bringing-together of skills, knowledge and both embodied and emotive connections to place and practice’ (Thurnell-Read Citation2014, 48). Craft brewers represent a form of neo-localism invoking branded embeddedness and provenance (Argent Citation2017; Danson et al. Citation2015Feeney Citation2017), creating connections to local places and their distinctiveness and uniqueness (Feeney Citation2017; Garavaglia Citation2020).

Their success has also been attributed to their distinctiveness and clear differentiation from the homogenized products offered by the established industrialized breweries, where geographical distinctiveness has been lost (Sennett Citation2008). It has been argued that the absence of linkages to any tradition helped brewers to express their identity and creativity in production, shaping a hyper-differentiated product (Clemons, Gao, and Hitt Citation2006; Garavaglia Citation2020). This hyper-differentiation strategy of continual innovation and experimentation, producing novel beers, to meet passionate consumer demand for diversity, authenticity and quality is a defining characteristic of the sector (Clemons, Gao, and Hitt Citation2006; Danson et al. Citation2015; Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018; Woolverton and Parcell Citation2008).

Craft breweries are commonly seen as anchors of local economic development and agents of neighbourhood revitalization and change (Barajas, Boeing, and Wartell Citation2017; Feeney Citation2017; Reid and Gatrell Citation2017). Acknowledged as pioneers, they commonly are first movers into economically depressed neighbourhoods (Barajas, Boeing, and Wartell Citation2017; Garavaglia Citation2020), exploiting resource-scarce spaces, using capitals overlooked by large-scale generalists (Argent Citation2017; Carroll Citation1985; Carroll and Swaminathan Citation2000; Clemons, Gao, and Hitt Citation2006; Cabras and Bamforth Citation2016; Elzinga, Tremblay, and Tremblay Citation2015). These pioneers are followed by other craft brewers collaborating, co-operating and clustering in space (Cabras and Bamforth Citation2016; Danson et al. Citation2015). This clustering facilitates the exchange and sharing of knowledge, contacts and advice, production facilities and loaning of brewery equipment and ‘cuckoo brewing’ (Dennet and Page Citation2017; Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018, Nilsson et al. Citation2018). This clustering also facilitates brewery hopping with consumers moving from brewery to brewery and the emergence of craft beer districts (Reid Citation2018).

Overall, there is a growing realization that ‘local, independent breweries strengthen local economies, promote sustainable development, and strengthen social history’ (Feeney Citation2017, 1). However, further and more detailed research is required into the potential role of craft brewing as an anchor sector for marginal areas, since: ‘at the very local level, especially in more rural areas, the findings are mixed. Some interventions have led to spin-off benefits for tourism businesses and other local food and beverage producers while others have simply offered a competitive edge to independent businesses’ (Ellis and Bosworth Citation2015, 2734).

This, then, is a challenger sector, which is shaking up organizational norms, structures and products, as it comes into being and grows in diverse national and institutional settings. Appendix A, adapted and extended from Drakopoulou Dodd et al.’s (Citation2018) study of the emergent Irish craft beer field, presents an exemplar overview of this sector, and also overviews studies into the global craft beer context. Appendix A is structured using Bourdieu’s forms of capital, to which we now turn.

Bourdieu’s theory of practice

Entrepreneurship has deployed Bourdieu’s wider work to study a diverse range of related entrepreneurial phenomena. In fact, as Tatli et al. (Citation2014) have so cogently argued, Bourdieu’s (relational) theory proffers a comprehensive conceptual toolbox for exploring entrepreneurship in context, as well as for overcoming the traditional, and often vexing, qualitative-quantitative, and structure-agency dichotomies. Bourdieu’s theory of practice Bourdieu (Citation1977, Citation1984, Citation1986) is especially suited to research which aims to explain ‘the nature, processes, and structures of embedded, contextualised, patterned interactions’ within craft sectors (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018).

Bourdieu’s work has inspired much entrepreneurship scholarship, from diverse perspectives. Detailed insights include, for example, Spigel (Citation2013) on the significance of Bourdieu for regional approaches to entrepreneurship, and his comparison of local and global sectoral norms, or habitus (2017; see also Tatli et al. Citation2014, especially the summary table on p. 623). Other leading entrepreneurship scholars have applied Bourdieusian theory to study, inter alia, the impact of behavioural norms on strategic power plays (Karataş-Özkan and Chell Citation2015); the challenges and strategies of transnational entrepreneurship (Drori, Honig, and Ginsberg Citation2006, 2009; Patel and Conklin Citation2009; Tersejen and Elam Citation2009); and winning legitimacy in the wine sector (De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2009c). Recent work has also explored the embedded community structure and dynamics of contextualized entrepreneurship (McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014; Gaddefors and Anderson Citation2017); and, even, the discipline of entrepreneurship itself Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2014, then, is an approach with a long, strong and growing pedigree in entrepreneurship studies. A brief re–presentation of Bourdieu’s main concepts follows.

Bourdieu sees a field as agonic social topologies: ‘bounded spaces comprising individual agents, who are linked together through relationships’ (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2016; see also Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 97–101; Friedland Citation2009, 888; Golsorkhi et al. Citation2009, 782; De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009a, 801, Citation2009c, 399–400; Levy and Scully Citation2007). Each field has different combinations of very specific forms of capital that are needed to play this game. In this landscape, actors are positioned relative to each other according to the overall amounts and relative combinations of capital they possess (Bourdieu Citation1989; Anheier, Gerhards, and Romo Citation1995). The practices and norms of a field – such as the craft beer sector – make up the rules of each specific game, the generative grammar of its practice, its habitus, or its ‘socially constituted system of cognitive and motivating structures’ (Bourdieu Citation1977, 76).

Our major focus in this study is on Bourdieu’s forms of capital, presented in his classic 1989 essay of the same name. Here, Bourdieu sets out detailed depictions of three forms of capital – cultural, social and economic – and the nature of conversions between these. To these, Bourdieu then adds symbolic capital, ‘the form that the various species of capital assume when they are perceived and recognized as legitimate’ (1989, 17). Economic capital, perhaps the most obvious, encompasses material, financial, and spatial assets. More complex are: ‘social capital (the latent resources embedded within networked relationships with others), cultural capital (knowledge, skills, education, and field-specific dispositions), and symbolic capital (legitimation and respect awarded by the field, typically in recognition of successful and appropriate attainment of other capital resources)’, (Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018, 643; our emphasis).

Cultural capital is particularly important in creative and craft worlds, being the encapsulation of the aesthetic in product, disposition and expertise (Bourdieu Citation1986), which facilitate reputation building (Pret, Shaw, and Drakopoulou Dodd Citation2016). Social capital represents the actual and potential value held by, and embodied in, relational networks, and the processes by which entrepreneurs build and maintain networks to leverage critical resources (Anderson and Jack Citation2002; Anderson, Drakopoulou Dodd, and Jack Citation2010, Citation2012; Batjargal and Liu Citation2004; Cope, Jack, and Rose Citation2007; Davidsson and Honig Citation2003; Drakopoulou Dodd and Anderson Citation2007; McKeever, Anderson, and Jack Citation2014). Symbolic capital is the reputation effects that then provide resources through legitimation of businesses and business practices. Crucial in a sector with new products, cognitive legitimation through labelling, symbols and other media of branding promotes the spread of knowledge about a new venture, particularly where new enterprises are likely to copy earlier entrants (Aldrich and Fiol Citation1994, 646; Zhao et al. Citation2017).

Recent studies have unanimously emphasized the heightened significance of non-economic capitals for entrepreneurship, and the interweaving of social, symbolic and cultural capital thus have special implications for socio-economic development, in the craft, cultural and creative sectors (see, for example, Dodd and Hynes Citation2012; Lee and Shaw Citation2016; Pret, Shaw, and Drakopoulou Dodd Citation2016; Shaw, Wilson, and Pret Citation2016). The multi-faceted nature of these entrepreneurial capitals allows us some purchase on the analysis of diverse forms of value, by moving us away from a focus on the purely economic.

Drakopoulou Dodd et al. (Citation2018) deploy Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, to study how global and local field norms emerge, within the craft beer sector. Their study identifies and compares the specific capitals which are valued and traded within both the emerging local (Irish), and the established global craft beer habitus. Appendix A presents a tabularized overview of their capitals analysis, for these two overlapping fields. We follow them in applying Bourdieusian analysis to the craft beer sector, but we extend this promising line of inquiry to explore how the four capitals, both in isolation and in combination, are deployed to organize the emergent craft beer field, and to facilitate creativity and innovation. We hope our focused explorations of growth, development and innovation capitals will contribute to deeper understanding of this policy-relevant sector, and the values which it creates, converts and curates. We hope, too, our findings may have wider theoretical implications for studies of rural craft sectors, and their regional impact.

As explained in the next section, we aimed to design a study which matched the sector, in both its innovative creativity, and its collaborative, democratic approach to knowledge. This decision was made:

for policy-support reasons – bringing multiple engaged stakeholders together to articulate their capitals strategies;

for epistemological reasons – bringing us close to the socially constructed world of the craft brewer, and giving them voice throughout the research process; and

for the obvious ethical rationales, around research openness and democracy.

Methods

The research ‘team’

Data were gathered through two whole-day participatory research events. These were shaped and attended by a multi-disciplinary, international team of academics, craft beer practitioners, and industry bodies from Scotland, the rest of the UK, and eight other European countries (see Appendix B). These events were organized by the academic team from the UK and drew on their own social networks. All participating practitioners were prominent members of their respective craft beer clusters, and several brewers held an official title of ‘prominence’, for example as head of the local brewers’ association. For others, prominence was inferred in terms of the symbolic capital they exhibited in their sectors (De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009b), objectified in the form of awards and public recognition (Pret et al. Citation2016). Brewer representatives were a mix of business owner or manager, head brewer, or key employee of the brewery. In the vast majority of situations, the manager was also the head brewer. The majority were thus central actors, with in-depth knowledge of existing practices in their clusters, and the efficiency, effectiveness and reach of these. The academic experts involved were from a variety of disciplines, from nine leading international universities. All were involved in research with artisanal food and drink businesses, and most had specifically explored the start-up and growth of craft beer firms. There were also representatives from key support bodies in the UK and Europe, including brewers’ associations and business support bodies from the food and drink sector.

Recruitment of participants was through a form of snowball sampling. Each academic was asked to bring one brewer from each of the countries that participated. In addition, representatives from key support bodies were recruited via personal contacts and announcements on support agencies email newsletters. All participants gave full consent to participation at the outset of the study and were free to withdraw at any time they wanted. All data have been anonymized and analysed at the aggregate level, ensuring that individuals and their craft firms were not identifiable, in accordance with ethical guidelines (Wiles et al. Citation2008; Guillemin et al. Citation2004).

Participatory research

Participatory research methods involve those people whose ‘life-world and meaningful actions are under study’ in all stages of the research process (Bergold and Thomas Citation2012, 192). They encompass methods of data collection that build on participants’ everyday experiences (Cook Citation2012), and focus on the perceived needs of a community, ‘defined in their own terms’ (Park Citation1999, 143). They are a particularly apposite method of research when researching communities such as the European craft beer sector as they allow the key actors of the community to collectively reflect on issues of importance to them, and with which they have experience (Elden and Chisholm Citation1993; Hense and McFerran Citation2016; Robertson et al. Citation2017).

This approach foregrounds participants and their understandings of context and culture in meaning-making (Elden and Chisholm Citation1993; Reason and Bradbury Citation2001) and solution-building (Robertson et al. Citation2017). Their increased use is a response to calls for a need for re-framing of the processes around data collection, analysis and understanding within qualitative social research (Hjorth, Jones, and Gartner Citation2008; Watson Citation2013; Zahra and Wright Citation2011). A key aspect of these types of methods is the notion of ‘safe spaces’, which encourage open discussion between participants and co-created solutions and resolutions to the subjects under study. These solutions are focused on a greater whole rather than individual goals, through a focus on community-level problems and outcomes (Hense and McFerran Citation2016).

Data co-creation

Both of the two whole day events were structured in conjunction with a sample of our target population of interest. Thus, the participatory design was an outcome of democratic collaboration with participants (Hense and Skewes Mcferran Citation2016). A key part of this process was in the design of sections of the workshops to ensure a ‘common language’ among all participants.

The frameworks used were introduced and discussed with participants at the beginning of each event. Participants then worked in multi-stakeholder teams engaged in a structured set of tasks. Industry representatives partnered with academics and experts to work on business growth challenges and solutions. The initial focus of discussion was at an individual-firm level. Then, participants worked in larger groups to identify commonalities in terms of growth challenges and solutions and reflect and debate on their impact for the sector as a whole. The frameworks thus enabled brewers and their partners to generate their own findings, to present, and to debate these, as well as to codify them in structured artefacts (Herr and Anderson Citation2005). This approach emphasized ‘withness’, in line with emerging principles of multimodal, multi-stakeholder, participatory (visual) fieldwork (Hassard et al. Citation2017), considering the problems and solutions for the craft beer sector as a whole through democratic collaboration (Reason and Bradbury 2006). In line with participatory research practices, participants were thus actively involved throughout the whole research process, from defining the problem focus to co-creating solutions. The role of the authors was as active participants in this process (Cassell and Johnson Citation2006).

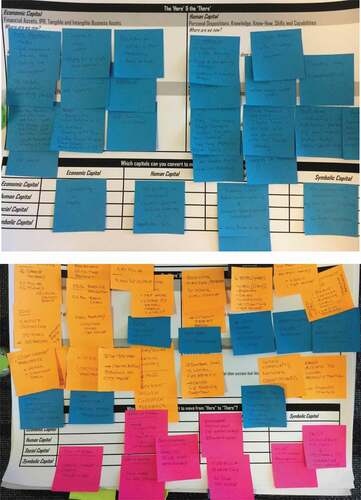

The data from the two events comprised: transcripts and video footage of conversations, debates and presentations from the workshops; filmed vox-pops with brewers, academics and support/policy agencies; co-created coding frames; posters constructed by participants and presented to and discussed with the group as a whole; and observational reflections from the four authors. The final dataset comprised approximately 36,000 words of transcript, 4 hours of video material, and 38 artefacts, including 17 maps of entrepreneurial capitals produced directly by participants themselves (see Appendices C and D).

Data analysis

Our role as authors in the next stage was identifying and articulating the subthemes and patterns which emerged from these workshops. Our broad analytic frame was taken directly from Bourdieu’s theory of capitals; this theory had been an integral part of our interactions with participants, who were trained in its meaning and application. Thus, a significant part of our initial coding was in fact carried out by participants themselves (see Appendices C and D).

Within our forms of capital analysis, however, greater analytic demands were placed on the authorial team, as we sought to identify the key subthemes and aggregate dimensions therein (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). Initially, two teams of two researchers each undertook iterative analysis of one event each, working through two rounds of data coding, first independently, and then in pairs. In this phase, data was classified as (mainly) providing evidence in relation to economic, social, cultural, and symbolic capital (second-order themes). Next, three further rounds of analysis took place with all authors, for both events, iteratively comparing and discussing our findings. We thus together identified emergent (first order) subthemes for each of the four forms of capital (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008; Easterby-Smith, Araujo, and Burgoyne Citation1999). The resulting data structure is illustrated in . For each such subtheme, extensive examples, vignettes and quotations from the dataset were collated into tables, to further enrich and explore our findings. Although space restrictions prevent their presentation here Appendix E provides an illustration of our analytical codes. Findings, by each form of capital, and their emergent second-order themes, are presented below.

Findings

Economic capital

Cash flow

When asked to identify the greatest challenges facing their breweries multiple respondents highlighted ‘cash flow, of getting cash moving through the business to drive other activities’ (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations). The need to pay duty on sales immediately, often prior to revenue receipt, was a specific challenge, for example. Export sales were identified as a promising solution to the cash flow issue, since ‘they can … pay upfront which is quite good for business that you get the money before you ship the product, so it’s quite a good arrangement’ (Group3, E1, round-robin presentations). Another way to generate strong steady cash flow to sustain and drive the business is by having a ‘cash cow’, that is, ‘a mass market beer in the portfolio that can be used to finance the other special products’ (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations). This was presented as a financing alternative to grants, or exploring crowd-funding, as a steady revenue generator. It demands, though, consistency and single-product volume, which is somewhat countercultural for the craft field.

Investment and growth

The dramatic growth in craft brewery establishment and sales prefaced many conversations, and was discussed with enthusiasm and passion, as a continued sectoral objective. Economic sectoral growth is also seen as a measure of the cultural developments with which craft beer is entangled: ‘In Ireland, the craft brewing sector is gaining 1% of the market share per year, so it’s not just like a cultural revolution, but it’s starting to become, as well, a business and an industry revolution’ (P2, E1, interviews).

For individual breweries, by contrast, economic growth per se was rarely mentioned as an objective. Brewery growth targets were routinely expressed in terms of volume of beer brewed, rather than as a sales figure. Indeed, there is, for some, a reticence to grow beyond small-scale craft brewing, as inimical with an artisanal identity and ethos. The longstanding CEO of ‘our’ largest brewery, who grew its capacity tenfold, explained the challenges of greater management demands, as well as the public’s perceptions of (now) the region’s largest independent brewer:

At that point, it sort of becomes a serious business. I wouldn’t say it’s never stopped being fun, but the management things of running a business come into it, rather than being more of a hobby or craft. I mean, we love what we do, we craft what we do, but we’ve grown. (P22, E1, intro presentations).

Growth potential was framed around local assets and infrastructure, as were growth barriers. Landscape, provenance, the lack of another local craft brewer, the demands of sourcing ingredients (typically from outwith the locality, for hops, especially), and the logistical demands of distributing widely from, say, a remote island, were all highlighted within our workshops as relevant. Spatial economic capital shapes craft brewery growth.

For many smaller breweries, though, the most significant problems are caused by ‘just not having the physical production capacity to ramp up to that next stage’ not least since ‘that would have required investment’ (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations). Brewing is capital intensive, and the scale of production and sales heavily dependent upon the capacity of physical brewing plant, which also sets the upper limit to a brewer’s goals: ‘we’re a four-barrel brewery; we’ve always been a four-barrel brewery, we don’t think we’re going to get bigger any time soon’ (P24, E1, intro presentations).

The other key high capital investment strategy is vertical integration, for example when breweries seek to enter the retail market, to ‘actually get our own outlet, either a brewery tap or a pub’ (P32, E2, interviews). Again, sectoral growth is high on the agenda, since ‘through that, we can not only serve our own beer, but we can support other independent breweries by getting their beer in as well’ (P32, E2, interviews).

Economic capital and context

To achieve sectoral, and brewery-level, growth, institutional support, especially tax and employment incentives are sought more widely. In Ireland, for example, smaller breweries pay much less duty than larger establishments, which is seen to have greatly facilitated the ‘immense growth in the past number of years’ (P3, E1, interviews). Such staged duty, as well as the capacity increase issues discussed above, lead to staggered and sticky growth trajectories.

Coming together in buying groups is discussed, too, following a Spanish example: ‘so we can go together to buy hops … and decrease the prices’ (Group1, E2, presentations). Again, the support of ‘the authorities’ is desirable for the establishment of such co-operatives, ‘by giving some funding’ (Group1, E2, presentations), and a wider need for additional economic capital to fund these is recognized.

The rationales for such state support often centre around ‘how craft breweries create new jobs in the rural regions’ (Group1, E2, presentations), with ‘very, very, very positive economic effects … the employment effects and regional and local development’ (P3, E1, interviews). Employment, the provision of novel tourist experiences, the creation of locally embedded beverages, the enactment of place and heritage through brewing, and collaborations with other local crafters – in all of these ways and more, craft brewers explained how they impact positively upon their socio-economic context ().

Table 1. Economic capital problems and potentialities

However, this is a mutual dependency, since spatial economic capital was particularly valued, in return, for the development of provenance and reputation. Embedding the beer itself within place matters a great deal: ‘it’s about organic, place, heritage, the sort of things that resonate with an awful lot of tourists … . it’s also giving them products that say, “this is very much about where you are at the moment, it’s about this place”’ (Group5, E2, presentations).

Cultural capital

Institutionalized cultural capital

Knowledge was a dominant theme: its creation, acquisition and sharing throughout the craft beer ecosystem. Both brewing expertise, and managerial, or entrepreneurial, competencies were much prized and pursued.

Crafting beer was seen as an expert art, and brewers continually innovate artisanal beers, in pursuit of the highest possible standards of aesthetic taste, and novel diversity. Some had engaged in formal training to achieve this knowledge, whilst others ‘turned my hobby of home brewing into a career’ (P32, E2, interviews). This transition from consumer, to domestic hobby producer, to commercial producer strongly influences the hands-on, artisanal, small-batch and experimental qualities through which craft brewers enact their skills and knowledge (see Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2018, for further discussion of routes to market entry for craft brewers). However, a need for formal systems was articulated in terms of an opportunity to tackle the problems of recruiting, training and retaining skilled staff, ideally through a national system providing

that ability to have a passport as it were with an agreeing sector to say, I know this person is appropriately qualified, I can recruit them, or I can give this person a qualification, therefore I can reward them and retain them (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations).

Equally, the need to sustain and communicate craft beer standards and quality through accreditation and within-sector regulation for production and packaging was seen to be a vehicle for ensuring only high-standard craft beer reaches the customer, thereby protecting market growth. Some workshop groups proposed ‘an EU craft brew institute’ (Group1, E2, presentations), or a ‘non-governmental regulatory body that is set up by a group of peers within the craft beer industry’ (Group2, E2, presentations), whereas others sought something like ISO9000, which could be ‘either industry-led or government-led’ (Group2, E2, presentations). Note the apparent paradox between the relational, informal and experiential exchange of knowledge which currently is seen to uphold quality standards within the craft beer sector, and the desire, as the sector matures, for these standards – and the skills which achieve them – to be formally codified and systematized.

Furthermore, brewers also desired to acquire what they perceive as non-core skills, around the business side of managing their breweries. Developing the skills needed to enter export markets was seen as a particular area of need, around the demands of rules, regulation, and labelling, and in terms of having the right contacts within international networks, since ‘a strategic way of entering them without contacts … is the biggest challenge’ (Group3, E1, round-robin presentations). Here, institutionalized cultural capital, in the form of formally taught export marketing skills, is sought, and seen as a replacement for a lack of international social capital. Brewers ‘know about markets like India and China and Saudi Arabia being potentially really good markets to enter, but because they don’t know anyone there, doesn’t make sense for them’ (Group3, E1, round-robin presentations). Others of these stated non-core skills were linked to the shared objective of educating customers about craft beer, and thus included marketing skills: ‘we also of course need to get some human capital. We need more marketing capabilities in order to promote craft beer as a product category’ (Group1, E2, presentations).

There was much direct discussion around the need to facilitate the customer journey of learning about craft beer, and to share knowledge with other members of the supply and distribution chain. The development of cultural capital within the customer base was seen as an end in itself, but also as a crucial marketing necessity. A key objective here was explaining to customers the complexity of even sourcing appropriate hops and grains, and, especially, the complicated knowledge ‘behind the different flavour of beer and … why mass-produced beer cannot reach that’ (P8, E1, interviews). This emerged as one of the core problems (and, indeed, potentialities) repeatedly identified by our participants, since ‘the key challenge would be to make would-be customers become aware, know what is real craft beer and distinguish it clearly from imitators’ (P8, E1, interviews). In part, such knowledge was felt to be required to validate craft beer’s premium price. This process was likened to the similar taste and production learning journeys which consumers and professionals alike undertake for wine and whisky. For one Scottish brewer, located on a famous whisky island, distillery tours also prime brewery visitors to experience beer education:

So, when they come in the brewery, they’re in that frame of mind. So, we have a rather unique situation where people have got time, and they’re learning, they’re learning loads. So, we can stand there with six or seven different types of beer in front of them and say okay, so you like that one (P24, E1, intro presentations).

When considering institutionalized cultural capital, participants also identified a clear need for formal and informal knowledge development with restaurant and pub staff. Beer sommelier education, food and beer pairings, more beer rankings, and tasting events with bars and bottle shops were all proposed. The need for knowledge development is still more pressing in (wine drinking) countries like Spain and Italy, where

often the craft beer is actually sold together with the rest, there is no presentation of the product, there is no education to the product. In those countries it’s quite important to educate the public and to educate the waiters in restaurants and pubs and pizzerias to present that (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations).

Indeed, some national differences were evident in the nature of the cultural capital which brewers aimed to share. In the British context, for example, considerable attention was given to encouraging wider cultural moves away from binge drinking of low-quality pints, and towards the sipping of fewer premium beers. What linked these national variations, though, was a shared focus on ‘the “winification” of beer’, and helping diverse people ‘enjoy the experiences tasting new beers creates’ (Group3, E1, round-robin presentations).

How is this institutionalized cultural capital shared? Both the established and more democratic online media are key vehicles for enhancing customer education – ‘opinion leaders, reviewers, “Untapped” blog writers, video loggers, or reviewers and writers of newspaper reviews’. Knowledgeable consumers themselves act as ‘your advocates, your ambassadors’ through ‘social media in particular, perhaps developing video channels’ (Group1, E1, round-robin presentations). Finally, brewers also talked about the need to educate policymakers as to the benefits of the craft beer sector, and to lobby collectively to see that new knowledge codified in legislation and support.

Objectified cultural capital

What of the beer itself, as a craft production? Much passionate attention and discussion was given to the endless creation of new beers, of novel objectified cultural capital. Creating new beers can also be a collaborative act between two or more craft brewery peers. Co-lab brewing emerged as quite an organic process, a spontaneous reinforcement of a growing friendship, as illustrated by an international co-lab dreamt up between brewers during socialization around our workshops. Since co-labs typically involve visits to one of the partnering breweries, the co-creation of new beer is a strongly social act of innovative interaction – an inherently relational process for the sharing of skills and knowledge through product innovation.Footnote1

Diversity and innovation are constantly sought, whilst brewers simultaneously (if paradoxically) pursue embeddedness in the locality, through provenance-giving local ingredients, and by drawing on local brewing tradition and heritage. Craft beer customers’ desire for diversity was seen to be a key driver of this paradox, as well as of constant recipe innovation, because ‘consumers now appreciate choice, want to buy into choice. So, the old days was about loyalty – people had just one drink’ (P22, E1, intro presentations). However, ‘the consumer wants to stay more local than ever before – although they do want to find discovery brands … what I think we see now is a lot wider portfolio of drinks, or repertoire drinking’ (P22, E1, interviews). This, exacerbated by extensive pub closures, results in brand dilution, because ‘more pubs are selling more choice, therefore there is less volume’ (P22, E1, interviews) ().

Table 2. Cultural capital problems and potentialities

Social capital

Local social capital and collaboration

In local terms, rich relationships and engagement with the craft beer community are especially valued, as well as links with incoming tourists (E2, presentations; Groups 1, 2, 4), ‘it’s not seeing your competitors as competitors, you see them as an opportunity to network and build upon your own brand essentially’ (P43, presentations). One of our participants, from the national tourism organization noted,

we’ve done a paper based on how we build the trends that we see on a consumer basis within tourism, how we can match it with the craft beer industry, and the three that came out were authenticity, provenance, and targeting a millennial market … so if you can build around your brand story of telling about what’s authentic about your product, what makes you stand out from everyone else, what’s the provenance aspect, so do you use water or barley from your areas, things like that. (P43, interviews).

Links and co-operation with other local food and drink players were highlighted as of significance, including restaurants (E2, presentations; Groups 1, 4), food and drink festivals (Groups 2, 5), and tourism (Group 1). Pre-embeddedness in localities, and within the craft beer (and other) networks provides latent social capital, which brewers then draw upon, or invest in, as they reach out to customers, distributors, peers, and institutional agenciesFootnote2:

A lot of what we talked about has been done very locally, so the local brewer, for them to make local relationships with other local partners, to grow their market, to penetrate new bits in the local market, and so on (Group5, E2, presentations).

Horizontal peer links with other brewers were highlighted, and, at the sectoral level, there was a strong perception that ‘we have social capital because breweries already have a lot of different collaborations going on’ (Group1, E2, presentations). As noted by a participant from a support organization, ‘collaboration has the potential to be a game changer for the craft beer industry’ (P40, interviews). The sociality and conviviality between craft brewers is inherent in the norms of shared beer drinking, so that the product itself is an integral element in the building and sustaining of social capital .Footnote3

Strong ties with other local independent brewers were also a key resource for collaborating on festivals and related events, since ‘all craft brewers are good friends … we then go out and reach out to small independent breweries like ourselves, rather than going to the big breweries; and we’re getting reciprocal arrangements’ (P32, E2, interviews). Reciprocity of interactions is perceived to be crucial, throughout the dataset, and is a matter of considerable pride and pleasure, as crafters work together to build agency and institutions, as in this Spanish example:

They are sharing costs, for example, for the materials, all the machinery that they need, and also, they are organizing events together, so they go to the fairs together, and also they are … sharing knowledge with each other (P8, E1, interviews).

Horizontal relationships with other local makers, including artisanal food producers, were perceived to be especially promising, and were welcomed as a way of enhancing local provenance within the beer itself. P24 collaborates with a community garden: ‘he’s actually got four hop plants going, and last year … we green hopped a beer’ (E1, interviews). P32, likewise, have been working with a local craft baker, as part of a national initiative on the circular economy, to make ‘a beer out of their spare bread, left over bread rolls’ (E2, interviews). Similarly, building relationships with tourist businesses offers ‘new possibilities for craft breweries … for example, craft brewery visits for tour groups and tour operators’ (Group4, E2, presentations). Brewery tourism itself was seen to have major social capital opportunities, by personalizing the face of craft brewers: ‘people come to your brewery and know who makes this product, and what the product represents’ (Group4, E2, presentations). Thus, fellow brewing, crafting and tourist businesses in the locality were all uniformly seen as key relational resources, not least as facilitators in the development of further, wider social capital within the value chain, to which we now turn.

Building social capital with customers and distributors

Vertical relationships are essential for reaching and educating the markets, and form a vital social capital resource comprising pubs, bars, the local tourist industry, exporters, and distributors. Building strong relationships with such partners was seen to be crucial to achieving these aims (E2, presentations). Digitally mediated relationships are also a significant reservoir of social capital for craft breweries, and the use of social media to develop and enact such relationships was singled out for special attention, ‘because that is the way that most people seem to engage with new ideas, new thoughts’ (P32, E2, interviews). Events, festivals and tastings also lend themselves to social media engagement, which has the additional benefit that ‘you know that’s going to be educating the market’ (Group2, E2, presentations). Social media thus emerged as a crucial innovation diffusion and communication channel, simultaneously building community, and educating customers. Customers’ own engagement with social media, presenting and celebrating specific beers, and reviewing and rating them on specialist beer fora, adds still further credibility and prestige to breweries.

Building national and international social capital and collaboration

Formal associations were also extensively mentioned as important social capital resources for craft brewers. Greater use could be made of these in the future, most especially in terms of quite formal peer craft brewery networks, which have already been identified as a potential agent in the establishment and accreditation of standards. The importance of peer learning networks was explicitly articulated, with clear recognition of the benefits of learning from ‘one of your peers who you respect from within the industry, who has a brewery, who knows how to make beer, coming in’ (Group2, E2, presentations). Also of note were links with formal business networks and public-sector associations, such as the sector’s UK independent brewing association, SIBA (the Society of Independent Brewers).

We are here as XXX to help businesses to collaborate, so whether it’s looking at the model or looking at the legals and the structure or the members’ agreement of how to work together. We’re here to help. It’s a free service and we’ve helped other businesses in sectors across the food and drink industry, for example, the craft distillers’ co-operative, doing very similar things. (P40, interview)

Rich personal ties to export contacts were perceived as a key social capital endowment: ‘yes, it’s that social capital that you need to develop, like really strong relationships with people who will bring your beer into their country … you have a relationship there already’ (Group2, E2, presentations). One idiosyncratic but highly interesting relational approach to growing international sales is that developed by some dark metal brewers, whose branding links strongly to this specific rock tradition, its language and symbols. This brewery ‘export’, in part, through attendance and sales at international dark metal festivals: ‘the festivals are basically every year, so next year you go back to the country and consumers get more and more used to your beer and maybe then they ask at the local shop to drink the beer during the year’ (WS1, group feedback, peer comment). Again, building face-to-face ties with consumers, building on shared interest and a strong narrative, is the key to exporting, even in this unusual format. ()

Table 3. Social capital problems and potentialities

Curiously, and against the grain of open collaboration, there was considerable resistance expressed to the notion of joint international selling and marketing activities. Brewers had anxieties of the extent to which their own brand would be able to stand out in, for example, a mixed pallet of Scottish beers sent to a specific export destination. By contrast, some expansion networks, particularly export connections, were seen to be weaker ties (in social terms), but of great benefit in supporting internationalization. Such connections included existing brewery and export associations, and some public-sector export support bodies. However, the number of these agencies was also questioned: ‘too many associations – not enough time’ (E2, Group3 poster). Nevertheless, desire for a pan-European craft brewery association was consistently expressed by several groups.

Symbolic capital

Craft beer narratives

Symbolic capital that resonates with consumers requires clear narratives. It demands consistent, authentic stories, often rooted within the heritage of locality, where the attributes of a specific place add weight to the narrative and branding of breweries. For example, some places have a lengthy tradition of beer making, as in the example of the East Midlands, ‘a traditional real ale base area with a lot of tradition – centuries tradition of brewing’ (AB, WS1, video interview). Other locales are strong tourist destinations, with related craft producers sharing in the creation of a food and drink experience for visitors. One island based Scottish brewery illustrates this aspect of spatial symbolic capital, drawing on the legacy and heritage of the closely related whisky distilling. As well as legitimacy, such place-based heritage also creates a pull effect, drawing customers into the area, and shaping their expectations of premium quality and provenance.

Beyond locality, the craft beer sector as a whole is seen as engaged in earning and defending symbolic capital. First and foremost, there is the conscious myth making of the small-scale crafter as against the macro brewers: ‘already now we have high quality and special taste associations connected to the craft beer, and we have this David versus Goliath kind of myth going on’ (WS2, group feedback).

Institutionalized symbolic capital

Symbolic capital’s authenticity can be embodied in awards, particularly at national and international level. Brewers felt that awards for their beers articulate value mainly to their peer group within the brewing community, facilitating market entry, as do the online reviews and ratings of informed consumers, for beers and breweries. This quite formal and institutionalized systematization of social capital is at the heart of reputation building, and legitimation, within the craft beer sector:

if you’re talking to somebody in Europe … the first thing those people will do when you mention your beer is clackety, clackety, clackety, clack on the keyboard, look you up on Untapped, on RateBeer, on all that. They check your beers. So, if your beer comes up saying ‘oh, it’s won this award, it’s won that award’, you are far more likely to be successful in developing that market. So symbolic capital is very important there (Group3, E2, presentations).

Risks to symbolic capital

These positive reputational effects are jeopardized by the sale of substandard ‘craft’ beer. Protection against this risk to the sectors’ collective capital – which is taken very seriously, and much discussed, is a major motivator of the desire for formal accreditation systems. As we have seen, all workshop groups independently proposed sectoral mechanisms to ensure and accredit the quality of craft beer, articulating and underwriting the meaning of craft in the brewing context. ()

Table 4. Symbolic capital problems and potentialities

Inauthenticity is also a reputational risk, and the temptations of succumbing to mainstream marketing norms was wryly discussed. This was rare, and appeared tongue in cheek, but stood out within the dataset for its instrumentality, and parody of attempted manipulations of symbolic capital. One (non-UK) academic participant reported back for his workshop group that ‘for a brewer exporting to the US, you might have to ham up. So, you might put a picture of the Union Jack on your bottle of beer … to say put a picture of baby Charlotte on the; Theresa May on the label, send it over. The Trump lovers would love it, wouldn’t they?’ (WS2, CMB, group feedback). Thus, craft beer not only carries positive reputational effects, but also recognizes more negative associations – the lack of symbolic capital – which some of its products and devotees both provoke.

Discussion

In our opening argument, we suggested that entrepreneurship might now be called upon as a tool to solve the problems and potentialities of pursuing ‘sustainable and sustaining growth’. We wondered what this kind of entrepreneurship might look like, at sectoral and regional economy levels, and sought to identify its form, its practices, its values created, converted and curated, as enacted in the natural laboratory of craft brewing. Our aim was to find ways in which we might solve the puzzle of supporting regional socio-economic growth, yet staying true to the principles of ‘Everyday Entrepreneurship’, and the ecosystem. We also sought to frame this road-mapping through a widening appreciation of capitals-as-value.

In line with our intuition and past research (see Appendix A), this (high-growth but pro-social) sector is characterized by very strong network ties, especially within the local places where craft brewers are embedded. Strong relational ties, characterized by mutuality of support and interests, extend throughout the value chain, embracing consumers, distributors, retailers, and, especially, other brewers. The richness of human interactions is celebrated for its own sake in this very relational value, which is often deliberately furthered and deepened through the sharing of knowledge.

The social capital inherent in these strong tie networks is, then, enhanced through intense focus on the creation and sharing of cultural capital within the sector, and on the importance of high-level knowledge for all, as to the variety, ingredients, recipes, traditions and innovations of craft beer. Not captured by superficial economic measures of growth, there are very significant value gains here, through the sharing of both localized heritage knowledge and highly skilled professional and commercial competences (marketing, exporting, production). Moreover, the community consistently works to co-create new knowledge, using very creative and innovative collaborative practices, which are perhaps resonant with other high-growth knowledge sectors, such as technology, or haute cuisine. Yet, again, these are tempered by a focus on sustaining and developing the wider craft brewing community, rather than growing the individual firm, including the depleted communities and overlooked places within which it embeds itself. We find competition between brewers articulated as a matter of craft excellence, and the just rewards for this, with individual financial and commercial growth downplayed, denied and distrusted. Especially important is to note that knowledge is seen as a shared asset, and that its value is shown to increase through collective extensions of that knowledge, and widening understanding throughout supply and distribution channels.

Aesthetic excellence matters enormously, as objectified cultural capital – knowledge enacted in great beers. Excellence in taste and skill is also celebrated through a plethora of awards, through online rankings sites, festivals, and associations. Being seen to be creative, performing crafting innovative excellence, is as crucial as enacting these practices, and such attributions are as vital here as in the world of haute cuisine (Koch et al. Citation2018). Comparisons to the world of wine highlight an appreciation for established institutional growth practices and paths which is, perhaps, a little surprising.

We found a firm desire for this craft excellence to be upheld through the introduction of accredited quality standards, again a perhaps surprisingly formal mode of legitimation through institutionalized symbolic capital. Although hardly novel, this usefully confirms a sectoral appreciation of wider mainstream recognition – un-othering – so needed when ‘firms initially lack external legitimacy due to their small number’ (Aldrich and Fiol Citation1994, 646). Here, the sector itself is seeking what might be considered quite conventional sectoral growth policy tools. Note, though, the re-shaping of these through a widened understanding of value, a deeper sense of the local, of environment, and of communal holding of assets. Note too, and highly democratically, that the acquisition of this rare and complex cultural capital is shared widely through the craft beer field in a variety of means, at every possible opportunity, and novel knowledge is often co-created.

The aim is not cultural domination, but rather the democratization of knowledge. Knowledge and social interaction combine to build ever wider communities of knowledge, with legitimation accruing as much from community building through knowledge sharing, as through the creation of novelty. This ensemble, through their embedded conversations, both co-creates the craft beer sector and negotiates its artisanal identity. It is a wide-ranging community of multiple stakeholders (Austin, Hjorth, and Hessel Citation2017). As argued by Zhao et al. (Citation2017), however, there is a conflict within such a sector between the drive to gain legitimation (conformity) and the individual (brewers’) pursuit and need to protect the distinctiveness of their product.

We note, too, the role of social media in democratizing knowledge – and of festivals, tastings, beer tourism in bringing people together for this purpose, which is interestingly resonant with scholarship exploring (folk) music (Van Eijck Citation2001; Peterson and Kern Citation1996; Peterson and Simkus Citation1992). The festival is a liminal, fluid social space where creativity emerges from chaos, and the boundaries of production and consumption are significantly blurred (Toraldo and Islam Citation2019). This is a sector characterized by passion and camaraderie, which drive the shared growth path, and must be appreciated as of value in their own right in supporting the field.

What emerges is an inclusive distributed model of sectoral growth, which stretches itself up, down, and along all its channels. Motivated by the passionate need to create, celebrate and share cultural capital, these assets are highly prized, whether expressed as new knowledge, embedded in traditional skills, or objectified in aesthetically excellent beers. Yet there is also a shrewd and practical recognition of the opportunities and barriers which regional and national institutions comprise, and of their role in sectoral growth. Beyond the romance, we also found a well-articulated and well-informed vision of a sector helped to grow into more formality, efficiency and professionalism.

Theoretical implications

Bourdieu’s language of capitals has provided a highly tractable lexicon here for extending our consideration of resources beyond the economic. We, amongst many others, have borrowed and bought into Bourdieu’s sociological lexicon to make sense of the world around us, often focusing on marginal contexts through this lens. Along with his forms of capitals, our main focus here, we showed above how Bourdieu’s theories of legitimation, social violence, fields, habitus, and power have also entered our collective work. Yet, as we noted at the beginning of this article, we now face contemporary environmental and socio-economic crises of an unprecedented scale. We ask here if it is time to move beyond Bourdieu, as we seek to reposition entrepreneurship scholarship in and at the edges.

Our study has revealed a field which is emblematically ‘folk’ and artisanal – yet simultaneously, professionally and intentionally focused on high growth through innovation – and characterized far more by internal collaboration than agonic strategic positioning. Does this different, emerging, craft-based form of agile distributed entrepreneurship, set against a context of ecosystem crises, demand a re-working, or at least a re-wording, of Bourdieusian approaches? We think perhaps it does.

To think of diverse ‘capitals’ has proved useful and enormously helpful in as much as it highlights social, symbolic and cultural resources contributing (at least as much) to the emergence of new ventures (new projects, new ideas) with the economic. With its Marxist overtones, ‘capitals’ speaks to power structures, as Bourdieu intended. However, its language can also imply that relationships, public standing, and knowledge (as well as money) are little more than individually held assets to be traded for better field position, and, importantly, that these are the only resources to be considered. This narrow understanding of phenomena can no longer be defended, on cosmological, ontological, axiological, or teleological grounds. It does, arguably, symbolic violence to Bourdieu’s own ethos, in facilitating the co-option of his work by an overly economic spirit. This study raises a clear empirical challenge also to this position; assets, values and capitals are created, curated and converted as community goods, in a very natural, routine and authentic fashion. If this is an agonic field, internally, then the game is mainly played for fun, for passion, for learning: winning might legitimate cult products and brewers, but excessive commercial success is presented as a by-product; growing the movement, and sharing the knowledge, are the key shared mantra here, the generative grammar of this habitus.

Here, too, we recognize the need to move to a post-Bourdieusian lexicon, which allows us to speak of the natural environment at all, and, in particular to speak of it as something other than a cost-less resource for our endless entrepreneurial consumption. Rather than capitals, we could write of endowments, for example. Not owned, nor bought, nor sold – unlike capitals– endowments are inherited, entrusted, stewarded.Footnote4 Or we could follow Korsgaard, Ferguson, and Gaddefors (Citation2015) and think about re-sources. Our verbs of processes around capitals are similarly infected with a very specific market metaphor: convert, exchange, trade, barter, invest, expend, build up stocks of. Where are our words for renewing, rebuilding, reusing, upscaling, improving, enhancing, rethinking, and donating to the common weal? We have been myopic in the lexical constraints we have imposed upon ourselves; we have stayed within the fixed boundaries of incumbent fields, instead of creating a vocabulary of entrepreneurship, of the in-between.

Conclusion

Informed commentary and analysis from representatives of European craft beer producers have confirmed a generation of innovative and growing enterprises that are both challenging the dominant oligopolists as a competitive fringe, but also cooperating and applying wider resources to generate space for dynamic growth at individual and sectoral level. The success of the craft beer sector in applying this capitals model can be seen in its achievements, both commercially and in terms of taste. As theorized by Bourdieu (Citation1986), this balance between competition and cooperation is being pursued through constant endeavours to secure economic, cultural, social, and symbolic capitals, many of which are perceived as a collective resource.

Across the sector craft brewers put an incredibly strong emphasis on the sharing of cultural capital, stressing a high-level knowledge as to the ingredients, recipes, traditions and innovations of craft beer. Integral to the craft beer movement, aesthetic excellence matters.

Traditional capitalism, and its models of entrepreneurship, assume profit maximization through striving for monopoly power, by cultural domination, specifically separating elites from the masses. Craft entrepreneurship, rather, strives for maximization of multiple forms of value, or capital, using knowledge and social interaction to build ever wider communities of knowledge, engagement and enactment. Cultural and social capitals interact here, with the craft beer communities and producers emphasizing the role of social media in democratizing knowledge and disseminating information, enthusiasm, and other intelligence about the beers. Our detailed empirical findings highlight a field which holds in balance both an innovative high growth ambition, held collectively, and a firm enactment of frugal, circular, local, foundational, pro-social and everyday entrepreneurship. This sustaining entrepreneurship calls into question some of the underlying assumptions and language of Bourdieusian theory, most especially around individual capital ownership and enactment, and the range of processes practised upon capitals (we do not only produce, trade and consume, but also steward, replenish, sustain and sacrifice for).

As engaged scholars, an integral part of the project design, our outputs included a policy white paper, on facilitating sustainable development and growth in the craft beer sector (Wilson et al. Citation2018). Six main policy and development priority areas emerged from the study: resourcing growth, marketing communications, market expansion, building skills, working with the value chain, and, crucially, legislation and support structures. Yet whilst these may appear entirely predictable requirements for sectoral and regional development, nevertheless in each case, as outlined in this paper, these areas were articulated within the context of innovative, distributed, knowledge-driven communities of practice, holding many resources in common. It is this additional way of being, this habitus of crafting growth together, which gives sustaining and sustainable value to the sector’s growth. These ways of being resonate with wider arguments for the ‘foundational economy’, and the rediscovery under Covid19 lockdowns of the need to rebuild resilience back into local economies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. It struck us that this bonding through collaboration process is very similar to that of academics striking up a friendship at a conference, and dreaming up joint research projects over pints of beer, which also then involves the conversion of budding social capital into the sharing of cultural capital (knowledge), and the creation of a novel cultural good (journal articles).

2. Unlike Cruz, Beck and Wezel’s study of Franconia Cruz, Beck and Wezel (Citation2017), our participants had not faced the problem of launching their ventures in locales with incumbent, centuries-old, craft breweries. Rather, they were pre-embedded in local communities prior to their launch of their new breweries.

3. However, note that brewing new beers together is not intended to be a means to sustained financial success: ‘I mean I don’t really see collaborating on a recipe and bringing out a beer together as a very profitable undertaking. It’s nice to do, but collaboration really is more about what you’re doing in the background.’ (P30, E1, intro presentations).

4. This is a prime example of the knowledge of the elite few, driving out the knowledge of the entrepreneurial many. The most long running conceptual debate in the family business literature is that of stewardship versus agency. Yet stewardship of resources, rather than ownership, is never, ever transferred into the language of the entrepreneurial mainstream.

References

- Aldrich, H. E., and C. M. Fiol. 1994. “Fools Rush In? The Institutional Context of Industry Creation.” Academy of Management Review 19 (4): 645–670. doi:https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9412190214.

- Anderson, A. R., S. Drakopoulou Dodd, and S. L. Jack. 2010. “Network Practices and Entrepreneurial Growth.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 26 (2): 121–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2010.01.005.

- Anderson, A. R., S. Drakopoulou Dodd, and S. L. Jack. 2012. “Entrepreneurship as Connecting: Some Implications for Theorising and Practice.” Management Decision 50 (5): 958–971. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227708.

- Anderson, A. R., and S. L. Jack. 2002. “The Articulation of Social Capital in Entrepreneurial Networks: A Glue or a Lubricant?” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 14 (3): 193–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620110112079.

- Anheier, H. K., J. Gerhards, and F. P. Romo. 1995. “Forms of Capital and Social Structure in Cultural Fields: Examining Bourdieu’s Social Topography.” American Journal of Sociology 100: 859–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/230603.

- Argent, N. 2017. “Heading down to the Local? Australian Rural Development and the Evolving Spatiality of the Craft Beer Sector.” Journal of Rural Studies 24: 503–527.

- Audretsch, D. B., and P. Moog. 2020. “Democracy and Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice.” 00 (0): 1–25.

- Austin, R., D. Hjorth, and S. Hessel. 2017. “How Aesthetics and Economy Become Conversant in Creative Firms.” Organization Studies 39: 1501–1529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617736940.

- Barajas, J., G. Boeing, and J. Wartell. 2017. “Neighborhood Change, One Pint at a Time: The Impact of Local Characteristics on Craft Breweries.” In Untapped: Exploring the Cultural Dimensions of Craft Beer, edited by N. G. Chapman, J. S. Lellock, and C. D. Lippard, 155–176. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

- Barth, S., J. Barraket, B. Luke, and J. McLaughlin. 2015. “Acquaintance or Partner? Social Economy Organizations, Institutional Logics and Regional Development in Australia.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 27 (3–4): 219–254. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2015.1030458.

- Batjargal, B., and M. Liu. 2004. “Entrepreneurs’ Access to Private Equity in China: The Role of Social Capital.” Organization Science 15 (2): 159–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1030.0044.

- Bergold, J., and S. Thomas. 2012. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung 37: 191–222.

- Bourdieu (1989). “Social Space and Symbolic Power.” Sociological Theory 7 (1): 14–25.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, P., and L. J. Wacquant. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago press.

- Burnett, K., and M. Danson. 2004. “Adding or Subtracting Value? Rural Enterprise, Quality Food Promotion and Scotland’s Cluster Strategy.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour and Research 10: 381–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550410564716.

- Cabras, I., and C. Bamforth. 2016. “From Reviving Tradition to Fostering Innovation and Changing Marketing: The Evolution of Micro-Brewing in the UK and US, 1980–2012.” Business History 58: 625–646. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1027692.

- Carroll, G. R. 1985. “Concentration and Specialization: Dynamics of Niche Width in Populations of Organizations.” American Journal of Sociology 90 (6): 1262–1283. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/228210.

- Carroll, G. R., and A. Swaminathan. 2000. “Why the Microbrewery Movement? Organizational Dynamics of Resource Partitioning in the US Brewing Industry.” American Journal of Sociology 106: 715–762. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/318962.

- Cassell, C., and P. Johnson. 2006. “Action Research: Explaining the Diversity.” Human Relations 59 (6): 783–814. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726706067080.

- Clemons, E. K., G. G. Gao, and L. M. Hitt. 2006. “When Online Reviews Meet Hyperdifferentiation: A Study of the Craft Beer Industry.” Journal of Management Information Systems 23 (2): 149–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222230207.

- Cook, T. 2012. “Where Participatory Approaches Meet Pragmatism in Funded (Health) Research: The Challenge of Finding Meaningful Spaces.” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 13 (Art): 18. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1201187

- Cope, J., S. Jack, and M. B. Rose. 2007. “Social Capital and Entrepreneurship: An Introduction.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 25 (3): 213–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607076523.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Cruz, M., N. Beck, and F. C. Wezel. 2017. “Grown Local: Community Attachment and Market Entries in the Franconian Beer Industry.” Organization Studies 39: 47–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617695357.

- Danson, M., L. Galloway, I. Cabras, and T. Beatty. 2015. “Microbrewing and Entrepreneurship: The Origins, Development and Integration of Real Ale Breweries in the UK.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 16: 135–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.5367/ijei.2015.0183.

- Davidsson, P., and B. Honig. 2003. “The Role of Social and Human Capital among Nascent Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (3): 301–331. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6.

- De Clercq, D., and M. Voronov. 2009a. “Toward a Practice Perspective of Entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial Legitimacy as Habitus.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 27 (4): 395–419. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609334971.

- De Clercq, D., and M. Voronov. 2009b. “The Role of Cultural and Symbolic Capital in Entrepreneurs’ Ability to Meet Expectations about Conformity and Innovation.” Journal of Small Business Management 47 (3): 398–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00276.x.

- De Clercq, D., and M. Voronov. 2009c. “The Role of Domination in Newcomers’ Legitimation as Entrepreneurs.” Organization 16 (6): 799–827. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508409337580.

- Dennett, A. and Page, S. (2017). “The geography of London's recent beer brewing revolution.” The Geographical Journal 183: 440–454.

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., A. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2021. “Let Them Not Make Me a Stone”—repositioning Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Small Business Management. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1867734.

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., and A. R. Anderson. 2007. “Mumpsimus and the Mything of the Individualistic Entrepreneur.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 25 (4): 341–360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607078561.

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., and B. C. Hynes. 2012. “The Impact of Regional Entrepreneurial Contexts upon Enterprise Education.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24 (9–10): 741–766. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.566376.

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., J. Wilson, C. M. A. Bhaird, and A. P. Bisignano. 2018. “Habitus Emerging: The Development of Hybrid Logics and Collaborative Business Models in the Irish Craft Beer Sector.” International Small Business Journal 27: 395–419.

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., S. McDonald, G. McElwee, and R. Smith. 2014. “A Bourdieuan Analysis of Qualitative Authorship in Entrepreneurship Scholarship.” Journal of Small Business Management 52 (4): 633–654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12125.