ABSTRACT

Building on Alistair Anderson’s work, this paper proposes transforming enterprise education to deeply address questions of sustainability, social justice and hope in our time of multiple and complex crises. New pedagogies, practices, vocabularies and connections help us to enact crises in entrepreneurial, ethical and creative ways, enabling us to remain hopeful in the face of unknown horizons. Drawing from critical pedagogies, from Epistemologies of the South, and from the wisdoms of Alistair Anderson, the paper outlines how transforming to a more, hopeful, socially just and sustainable enterprise education could move us beyond present alternatives. We suggest that transforming enterprise education (TrEE) would better facilitate students as ethical change-makers when they engage with their worlds, and its unseen future horizons. TrEE emphasizes the time needed for questioning dominant meanings and space for experimenting with new ones. It invites re-placing us in the margins and with the excluded. It takes an expansive view of the ecosystem, and places enterprise within its wider context. It focuses students, teachers, entrepreneurs and various other stakeholders in learning together with the non-human and relies on sustainable stewardship, social justice and hope at the core of transforming enterprise education.

Introduction

Alistair Anderson’s living, both professional and personal, was heavily invested in foraging, forging and following connections. He knotted together an interwoven tapestry of thought and practice, tying in the storylines of his myriad collaborators, his own global community. He always, always, wanted to tell us a story, the next chapter, a story that wove together so many strands of our shared musings, imaginings, journeys and adventures. Like all truly great artists of the conversation, Alistair listened, too; encouraging other(ed) voices, helping them to pick out unlikely ‘patterns’ in undervalued places. Above all, Alistair engaged; with kindness, and wisdom and wit.

Much of this special issue focuses on Alistair’s monumental contribution to entrepreneurship theory, and rightly so. Here, we turn instead to an area of his work, which is perhaps slightly less familiar; enterprise education. Alistair’s final publications were a call to arms, a manifesto demanding we re-think entrepreneurship scholarship (Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021), and find new re-sourcing paths to co-creating depleted communities (Bensemann, Warren and Anderson, Citation2021). Some of us were also playing with early drafts with Alistair, translating these ideas into pedagogy, when we lost our master story-weaver. This paper is one way for us to continue these conversations with him, extending his legacy, and honouring his memory.

Our objective here was simple, if ambitious: extending Alistair’s last manifesto beyond research and community engagement, and knotting it into enterprise education. How might we start re-thinking some teaching fundamentals? How to respond to what Alistair and his co-authors saw as the ‘triple crunch of the economic, environmental and socio-spatial crisis’ (Korsgaard, Anderson, and Gaddefors Citation2016)? What is the nature of enterprise education in a context of continual complex crisis? And how may our educational endeavours become transformed, transforming and transformative, enacting new alternatives embedded in sustainability, social justice and hope? Our own hope, here, is to contribute to Alistair’s legacy by connecting and extending key areas of his work, and that of his other fellow-travellers, (back) into the field of enterprise education. We follow their interwoven threads, knotting them together, and entangling ourselves in these meshworks of theory and practice (Ingold Citation2008). This is the complex tapestry we hope to explore here, wondering hopefully how, like Alistair, we too might become agents of transformation in an era of crisis. The question we pose is, in short: how might we set about transforming enterprise education to be more hopeful, sustainable and socially just – more AndersonianFootnote1 ?

First, though, we ask ourselves, briefly, broader questions of understanding, as to the nature of enterprise education in a crisis context, revisiting Alistair’s own work, and then following the threads of his trails across the edges and into newer landscapes. Next, we build on these insights to explore what transforming enterprise education might entail in terms of sustainability, social justice and hope, and what it might thus look like. We ask how these elements might be woven together to support our students in building better places, and we illustrate our suggestions with some concrete examples. Finally, we attempt to weave our threads together into what we hope is an inspiring fabric for creating a transformative, socially just, hopeful and sustainable enterprise education.

EnterpriseFootnote2 education in a crisis context

The nature of the subject, its complexities and contexts make entrepreneurship difficult to teach (Anderson and Jack, Citation2008). Nevertheless, society places an increasing priority on enterprise and universities are recognized to play a critical role in ‘shaping attitudes, supplying knowledge and generally enabling our students as enterprising customers and endowing them as entrepreneurial products’ (Anderson and Jack, Citation2008, p. 259). In many countries throughout the world, enterprise education continues to rise to the top of the political agenda (Anderson and Jack, Citation2008), even more so in these current times of crises. As the number of university courses in entrepreneurship continues to grow, so do the number of students. Through this demand for enterprise education, places of education strive towards the development of creative individuals who can think for themselves and see opportunities for change, able to apply imagination to real-world problems (Anderson and Jack, Citation2008).

Unknown futures demand new pedagogies, which focus on positive, hopeful transformations, and ask us to take seriously our responsibilities in shaping an entrepreneurship that is environmentally positive, socially inclusive and ethically aware. ‘We set the institutional norms for entrepreneurship education (Jack and Anderson Citation1999): we shape the voice, the thoughts and the words of the next generation of entrepreneurs’ (Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021). This requires re-thinking, re-making, and re-directing pedagogical efforts so that the next generation of entrepreneur/ial people can find ways to turn enterprise into more hopeful futures. This involves learning about the connection between entrepreneurship, enterprise, and destruction as much as it involves engaging in imagining and enacting in less destructive and more constructive directions.

Our spirit of hopefulness is both inspired and informed by Alistair Anderson. It is inspired by his passionate commitment to creatively progressing entrepreneurship as a vehicle for inclusive, positive sustainable change and his demands for entrepreneurship (and those engaged with its research) to meet current challenges. It is informed, throughout, by a deep reflection on Alistair’s work, and the futures this might lead us to. Building on strong recent pedagogical directions (see e.g. Berglund and Verduijn Citation2018; Verduijn and Berglund Citation2019; Berglund, Hytti, and Verduijn Citation2020a, Citation2020b), we reflect here on how we might transform entrepreneurship education, not to just help us cope with crises, but to ethically enact entrepreneurship through crises. The question we pose here is, how might we set about transforming enterprise education to be more hopeful, sustainable and socially just?

This repositioning contributes to the further decoupling of entrepreneurship education from the creation of high-growth businesses (see, e.g. Galloway and Brown, Citation2002; Gibb, Citation2002) and from the fostering of entrepreneurial citizens that reproduce the status quo (Brunila, Citation2012; Torres‐Santomé Citation2018). Alternative thoughts to alternative thoughts are needed, cultivating entrepreneurship as a practice, which challenges the taken-for-granted; that is, a transformative practice of enterprise that envisions, co-creates, and enacts new, sustainable and socially just interactions, while remaining hopeful in crisis and in the face of uncertain future horizons.

Transforming enterprise education through sustainability

Repositioning studies of place requires, we have suggested, embracing the biosphere by, at least, ensuring our models and theories take good account of the natural environment, as well as the built, in this most human of epochs, the Anthropocene, and from the perspective of citizens of the whole cosmos (Heikkurinen et al. Citation2019). There is space, even, for work that returns to the fundamental building blocks of our entrepreneurial relationships with nature: water, earth, land, fire, air, sky, woods (Hjorth and Steyaert Citation2004, Citation2010; Steyaert and Hjorth Citation2008). (Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021, 17)

Our starting point is the hope and horror of living in a crisis society, and our role in shaping transformative, sustainable enterprise, capable of navigating the horizons of unknown futures. The major crisis which we have collectively brought upon ourselves and the planet is the environmental climate disaster unfolding around us. Creating and curating value in sustainable ways is a core principle of leading entrepreneurship scholarship, which sits well with the approach taken here to teaching (Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021).

The principle of sustainability offers an ethical value creation, where the entrepreneur wants to protect local ecological resources but at the same time enhance local social conditions (Anderson Citation1995; Shrivastava and Kennelly Citation2013; Kibler et al. Citation2015). Anderson (Citation1995), Jack and Anderson (Citation2002) and McKeever, Jack, and Anderson (Citation2015) see sustainable entrepreneurship in a much broader sense than, e.g. the UN’s 2030 Agenda for sustainable development, and see that through the partnering that exists between entrepreneurship and place, sustainability also relates to the social practice of entrepreneuring, sustaining communities and societies through time and in place. Anderson (Citation1995), Jack and Anderson (Citation2002) and McKeever, Jack, and Anderson’s (Citation2015) socialized view of entrepreneurship offers a type of entrepreneurship which happens because of a strong emotional attachment to place and the wanting to do right because of such an attachment. This often extends beyond place-based entrepreneurship to place-attached enterprising (Kibler et al. Citation2015; McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015), where place becomes a resource through which people are challenged to gain agency (Anderson and Gaddefors, Citation2016, Gaddefors and Anderson, Citation2018, Berglund, Gaddefors, Lindgren, Citation2015).

We have, it is clear, an incontestable duty to integrate the environment, the planetary context, within all our teaching, and to set the socio-economic transformation of the margins within that frame. Transformative, frugal, grassroots, teaching – alongside the planet, and its marginal peoples and places – focuses on re-sourcing and re-building places. Such an approach is also best placed to study and facilitate transformation at the margins theoretically. It has, after all, proven so successful in driving heterodox economic development policy that it has won the ultimate academic legitimation, the Nobel Prize in Economics, in 2019. At the very least, we can aspire to fully embedding sustainability and stewardship into our class content. We can also look to new pedagogies emerging from those who specialize in embedded and ecological scholarship and engagement. In all of these arenas, the role of (diverse ‘forms’ of) entrepreneurs in making place will demand our attention, too.

Ecosystem models, too, we also believe are currently missing a significant trick by assuming away the natural world, which gave its metaphor birth (if, indeed, it is a metaphor at all). It is certainly true that ‘an entrepreneurial ecosystem obviously cannot be the same as a natural ecosystem such as a forest or a specific habitat’ (Kuckertz Citation2019, 1). Yet it is fundamentally true that each and every entrepreneurial ecosystem is embedded within the wider natural ecosystems which predate, shape and encompass it. Rather than struggling to integrate the planetary context within our own metaphorical models, transformative enterprise education suggests we attempt the reverse, and integrate the entrepreneurial ecosystem, theoretically and empirically, within its natural context. Gaddefors and Anderson’s (Citation2017) wonderful re-telling of the role sheep played in one village’s entrepreneurial development may provide inspiration here (as well as a smile or two). The better we understand the planetary context and its nature – the natural places, particularly at the level of the local ecosystem – the better we understand how to enact entrepreneurship education in more hopeful and transformative ways, immersed in that environment. In so doing, we not only enact crisis entrepreneurially, but perhaps help mitigate against future crises as well, too.

The importance of this extends well beyond shouldering our environmental responsibilities, as teachers and citizens. Growth-and-consumption-based approaches to ecosystems assume – and sometimes even promote – competition for resources, churning, and geographic clustering of productive resources. Rather, and aligned with, for example, Pansera and Fressoli (Citation2020), we propose that it is possible to innovate without exhausting planetary resources, and to teach organizational practices that decouple innovation from growth, developing entrepreneurship education as sustainability education (Hermann and Bossle Citation2020). Transformative enterprise education in this sense is about instilling felt needs to transform, even if embracing the unknown.

Perhaps, a humbler appreciation of enterprise as embedded within larger planetary contexts will allow us to widen and deepen our use of the ecosystem metaphor, recognizing the values of symbiosis, of creating as well as destroying resources, of nurturing, sustaining, migrating; of seasonality, locality, frugality and co-operation. Equally, the natural ecosystem, whether as metaphor or applied anthropological truth, is infinitely diverse, inherently heterogeneous, and rich in the diversity, which fuels entrepreneurial bricolage (Anderson Citation1998). Of its nature, a greater engagement with the full panoply of locally available endowments and relationships – in a sustainable fashion – is also likely to challenge learners’ (and scholars’) perception of one-size-fits-all, simplistic approaches. One example of how this might happen is provided below.

Example 1: Every Tree Tells a Story

Strathclyde University scholars from a variety of backgrounds have come together with Glasgow City Council and other partners to found a citizen-science-and-art exploration of the city’s trees, as an experiment in community policy making. ‘Every Tree Tells a Story’ brings together educators, policy makers, artists, architects, planners, and entrepreneurial development scholars, to elicit through stories the grounded experience of our fellow-citizens. A pilot project with a local primary school (from a depleted area) led to the creation of a book, and a video, for example. (Not all our educational work takes place within universities, after all.) https://everytree.uk/

Our teaching invitation is thus to develop classes, projects, assignments and collaborations which take an expansive view of the ecosystem, and place entrepreneurship within its wider planetary context, be that local, regional, global, or all three. Embracing, studying and teaching natural ecosystems as the primary entrepreneurship context is, helpfully, entirely complementary with recent calls to deepen the focus on place, and place-making, within entrepreneurship (Welter and Baker Citation2020). Here, we are in luck. Ecological and Environmental Education is a creative, dynamic, heterotopic and multi-disciplinary community of practice, with much to inspire and inform us (Wahl Citation2019; Johnston Citation2009; Loureiro and Torres Citation2014; Tozoni-Reis Citation2006). This can help both teachers and students to develop more thoughtful relations to our commons and the planet.

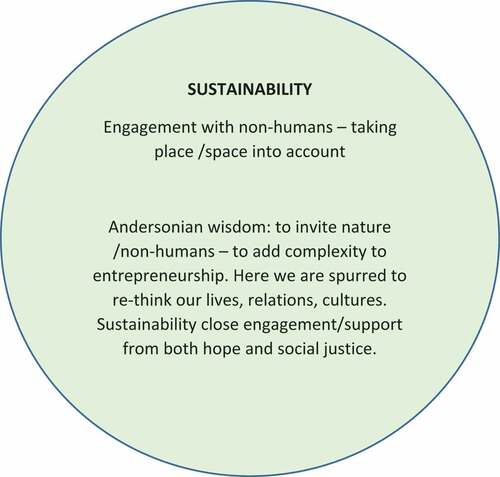

We concur with and build on Andersonian wisdom to propose that enterprise education be transformed, and become transformational, first and foremost by beginning at the grass roots to make sense of the non-human. Our trees, forests and woodlands, or our waterways, offer an exciting, hopeful route into re-thinking essential elements in our local ecosystems. This is an invitation to nature, to engagement with non-humans, taking place and space into account, and adding complexity to entrepreneurship. As such it is perhaps the complex nature of the untwining, re-twining, entwining and knotting together that is relevant to ‘class’ here – where we are all spurred to re-think our lives, relations, cultures, and to be humble, understand mutuality in recognizing that environmental sustainability also entails close engagement and support from both hope and social justice. summarizes our insights as to transforming enterprise education through sustainability.

Transforming Enterprise Education through Social Justice

Interventions focused solely on the level of the individual, and impregnated with atomistic assumptions about the “nature” of entrepreneurship, are unlikely to prove as effective as those that also engage with structure. … This populist hagiography of the atomistic entrepreneur lends especially itself to political rhetorics that espouse a wider vision of the importance of individualism, and is excluded from other, more collectivist political approaches. (Drakopoulou Dodd and Anderson, Citation2007, p352)

Addressing questions of sustainability call for our simultaneous attention to the questions and challenges related to social inequalities. We cannot ask people to survive cold winters without coal if they do not have the financial means and other resources enabling them to resort to more sustainable energy. Indeed, social and economic changes were already entangled in Schumpeter’s thesis on economic development. Nowadays, social change is often used to emphasize alternative dimensions, as in social entrepreneurship. We ask here, though, how to avoid replicating current institutionalized constraints, and unwittingly re-inscribing the status quo, our history and present practices, by, for example, re-othering marginal people and places. How can we avoid re-constructing tacit dialectic relationships between social and economic? Real transformation must surely overcome our persistent tendency to construct the (economic) centre as ‘helping’ the (social) margin, othering the edges, the joins, the depleted communities as places-to-be-helped. This trend of course perpetuates dominating understandings of entrepreneurship and change instead of transforming them.

A social justice informed by Epistemologies of the South (de Souza Santos Citation2014, 124) is about making a (radical) division, in the sense of drawing an abyssal line, between what is conceived as dominating, metropolitan and noticeable, and that what remains below the surface, and is consequently unacknowledged; the subaltern. Recognizing, and acknowledging this line, and its accompanying tensions and exclusions, is pivotal. Such tensions and exclusions (and concomitant inequalities) exist on either side of the line. On the dominating side, inequalities can be regulated with the mechanisms provided by a social state, such as laws, (human) rights, and democracy. On the other side of that line, equality is almost unimaginable. There, annexation and violence rule.

Knowledge, and knowledge-creation, at the dominating side of the line is perceived to be the (only) ‘real’ and ‘true’ knowledge. Epistemologies of the South challenge this, and suggest instead that we also embrace as valid the knowledges, and knowledge-creation, that take place on the other side, leading to an ‘ecology of knowledges’ (de Souza Santos, Citation2019, see also Braidotti Citation2019). Another example is from critical pedagogue Paolo Freire and his thoughts on ‘conscientization’, where learning centres on perceiving and exposing contradictions – social, political or economic. Freire expands the social/economic duality by including politics (one example of a power dimension). This makes it possible to problematize the inequitable relationship between margin/centre – ‘abyssal thinking’, in this vocabulary. It is only by problematizing abyssal thinking as an opening act in enterprise education that we can also mobilize, enact, practice and teach alternatives to the alternative. Post-abyssal pedagogies thus enables addressing social inequalities in more communitarian, grounded, and reflective fashions, and thus entail hope of more sustainable and just futures.

With inspiration from Anderson’s work, we see a need to turn away from a focus on the over-individualized notion of the entrepreneur and entrepreneurial processes. Instead, we see the potential of enacting enterprise – and within it, entrepreneurship – in all kinds of places and through a new understanding of the meshworks which thread, knot and bind together people, places and resources into a fabric and one, which can be sustained through time and space. We propose the need to move beyond dualistic understandings of economy and society, beyond means-ends conceptualizations and beyond centre-margin assumptions.

Embracing socially just education means much more than inviting teachers to collaborate. It means to going to the depleted edges of society, and seeing the story lines, the journey paths, the connections, and the (diverse) resources which sustain these seams joining society’s edges together. A socially just acknowledging thinking and knowing as relational activity (e.g. Braidotti Citation2019). Here, inner flexibility and unsteadiness are conceived as opportunities both to question theoretical notions and to encourage procedural creativity (Rodríguez-Romero Citation2020). Imas and colleagues (Citation2012) demonstrate how barefoot entrepreneurs (beggars, vendors and people collecting rubbish or dancing or playing music on the streets to make a living) engage in practices filled with meaning, values and relationships that align with our prominent views of entrepreneurship, yet, surely, not with that of the ‘common’ entrepreneur. Below we offer one example of how what we describe here is being achieved.

Example 2: Socially Just Enterprise Education Curriculum in Galicia

In late 2021, the Galician authority for Education (Consellería de Educación-Xunta de Galicia) piloted a training course for further/technical education teachers, in ‘Transformational Entrepreneurship’. The class content was designed to make space for just such new meanings, and to highlight non-hegemonic ways of entrepreneuring. Examples of class sessions in course include

How to design business projects using a co-operative and collaborative model

How to organize a financial structure from an ethical perspective

How to build mutual support networks within the Social Solidarity Economy

How to place life in the centre with feminist economy

How to design sustainable entrepreneurship.

Socially just enterprise education proposes, and encourages, altering habitual thinking, and starting to look with ‘new eyes’. This asks us to create a space in time to learn how entrepreneurship, and enterprise, are typically constructed, deconstructing it before reconstructing, together, more just alternatives to the alternative. Such movement entails relegating dominant meanings to create space for experimenting with new ones (Berglund and Verduijn Citation2018). Garmann Johnsen et al.’s (Citation2018) ‘conceptual activism’, for example, is ‘a way of teaching that aims to utilize philosophical concepts in the classroom’, p. 119) to unlock alternative viewpoints, and make space for reflection (see also Gaggiotti, Jarvis, and Richards (Citation2020) on pedagogic process and emerging the liminal/liminoid, following Van Gennep [Citation1960], and Turner [Citation1967, 1969, 1987]). This allows students to experience transitioning, transforming, and the concomitant dwelling in ambiguity and uncertainty, that is part and parcel of enterprise. Indeed, such practices may make it possible to prepare our learners to embrace the unknown.

Transformative enterprise education (TrEE) for social justice also implies striving for diversity, instead of inviting archetypal role models representing a niche and elite group of entrepreneurs. Socially just enterprise education consciously avoids further reinforcing the stereotypes of the very specific 1% enterprise form: homogenous in nature, and unrepresentative of anything, except the privileges of cognitive capitalism. In so doing, it also allows our curricula to avoid these practices which ‘institutionalise the winners and losers’ logic of market competition’, where ‘so-called “entrepreneurs” are encouraged who invent ways to risk collective assets and wealth’? (Valentine, Citation2018, 5).

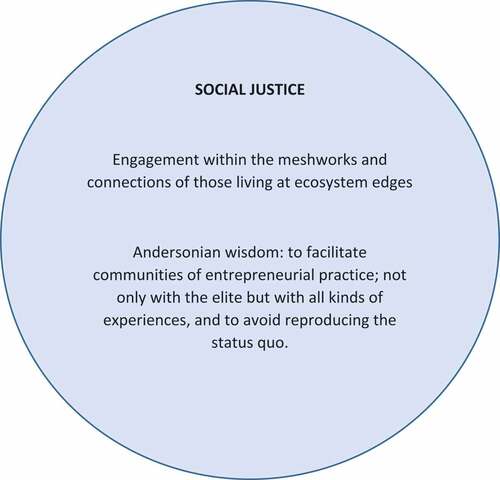

Pedagogies for social justice suggest that knowledge is being created in the process, not something ‘already-made’ that has to be ‘transmitted’. So, they advocate participatory learning arrangements, the creating of communities of (co-) learners. And not only that, it also – building on critical pedagogies (bell hooks Citation2003; Freire Citation1994; Darder Citation2017; de Souza Santos, Citation2019) – offers the opportunity to learn from, and with, the marginalized, such that education can become truly emancipatory. This means a (constant) crossing of (the abyssal line at) the margins, bringing the dominant side to the marginal one, and vice versa. summarizes our insights as to transformative enterprise education and social justice, and reminds us that equity is a precursor to hope.

Transforming enterprise education through hope

Our strengths, as universities, lie in developing higher level skills and nurturing analytic ability. In short, the production of reflective practitioners. We consider reflective practitioners to be individuals who, through their knowledge and critical ability, are capable not only of starting new businesses but also of ensuring the continuing viability of businesses by enhancing the capacity for them to develop through a richer understanding of the entrepreneurial process. (Jack and Anderson Citation1999, 211)

Why emphasize hope? Hope indeed offers an alternative thought to the alternative thoughts; a brighter thread. For it is in the very midst of crises of the global south that influential critical pedagogue Paulo Freire has situated hope. In Antonia Darder’s book Re-inventing Freire: A pedagogy of love, she returns to Freire’s key message that hope gives opportunity to re-direct the future, dismissing historical determinism and developing paths that lead to the ‘deepening of freedom and social justice’ (Darder Citation2017, xiv). Hope is a moral imagination to re-think – how can we otherwise act innovatively and entrepreneurially? Hope is a possibility to live ‘increasing solidarity between the mind and hands’ (Paulo Freire et al. Citation1997, 33).

Building hope, therefore, through education seems critical but also logical, and doubly so for entrepreneurship education within a crisis society. It is the fuel for engaging with the complex challenges involved in our attempts to save our Planet and create a more just world. It is not, primarily, hope for ourselves which we are proposing here: it is perhaps not even hope for our students, on an individual level. Rather, it is hope on a systemic level that we seek to nurture, real hope for transformation by engaging across frontiers, within in-betweens, at the margins. Such hope is predicated on authenticity of interaction across these marginal edges, and on addressing power dynamics, as pedagogies and epistemologies of the South also argue.

If we are to nurture the co-creation of hopeful and just futures, then this cannot yet again be simply from our own position of institutional privilege. Rather, we ultimately need an engagement with the perspectives of those who have systematically suffered injustices, dominations and oppressions (bell hooks Citation2003) – an engagement with knowledges and practices that have resisted, despite all, enabling and empowering social transformation (de Souza Santos, Citation2019). As such, the Epistemologies of the South propose to make believable and urgent the need to recognize and embrace diversity in the world, in order to amplify the various knowledge experiences and conversations, and to become more deeply familiar with them. This, we believe, is our challenge in co-creating pedagogies where authentic hope can be nurtured.

If we take entrepreneurship as being most archetypally enacted at the margins, along the in-between interstices, then is it not – indeed – the knowledge of these marginal places which

Example 3 – Critical Enterprise Pedagogies of Hope

How, though, can the entrenched fundamentals of enterprise education be reworked in the pursuit of transformational pedagogies of hope? Berglund and Verduijn’s (Citation2018) book offers the fruits of their engagement in dialogues with colleagues, reinterpreting how the ‘about, through, in and for’ concepts could be translated, with the help of critical scholarship, to revitalize entrepreneurship education, better grounding students to become more aware decision-makers. The book illustrates how the practice of learning in the classroom can be about enacting entrepreneurship in diverse forms, whether through projects, through NGOs, setting up an artistic performance, enacting flash mobs, social engagement and interventions, or making films. The ‘about’ of entrepreneurship education deals with problematizing the grand heroic narrative of entrepreneurship, perhaps by using the very knowledge provided by critical entrepreneurship pedagogy. The ‘through’ of entrepreneurship education implies engaging with students in dialogue and critical reflection – and not about following instructions and rigid (business) tools. We suggest that our teaching interventions should reflect this (entrepreneurial) move and prepare our students to facilitate re-thinking, re-acting and re-learning entrepreneurship, becoming grounded as ethical change-makers in the entepreneurialised crisis society as they grow and move forward to engage with their world.

should be studied? Marginal knowledge ecologies offer new ways to represent diverse epistemologies of these (edge-) worlds, to show up silenced knowledges, and to challenge the institutional colonialization of these knowings (Quijano Citation2005; de Souza Santos, Citation2003, 2004). Together with our students we can further explore these knowings, and immerse ourselves in these marginal ecologies of knowledge, beyond the edges, getting over the abyssal divide.

Such an approach likely means centring embedded entrepreneurship, taking its local (and sectoral) knowledges seriously, and discovering new socially progressive pedagogies to do so. Again, the Epistemologies of the South remind us that to re-place ourselves in the margins means crossing the abyss of (colonializing) centralized knowledge, and engaging with the wisdoms, practices, crafts, and cultural traditions in and of the edges (de Sousa Santos, Citation2019). And with the wisdom of everyday enterprise.

Co-creating embedded learning communities is a more complex task than cookie-cutter reproduction (Lepistö and Hytti Citation2020) but it speaks to all that is best, and most hopeful, in enterprise education. Making connections across meshworks of diverse learner groups, for example, allows for interactive peer-to-peer learning through knowledge bricolage. Although depleted communities and their ecosystems may appear poor in terms of resourcing, this is typically true mainly of economic forms of capital. The margins, the joins between ecosystems, their overlaps, are amongst the resource-rich environments for all species, and it is precisely this localized and highly diverse – if frugal and humble – munificence which spurs structural hope along these lines. Indeed, marginal ecosystem – ecotones – have shown us examples of ‘depleted’ communities with quite exceptional richness in cultural, social and symbolic capital, many of which we have retold here, sheep and all. Leaving the centre to its own economic devices, and embracing the embedded everyday lines of story and place relocates hope structurally to a post-abyssal set of alternatives to our current alternatives of despair. Transforming enterprise education allows for embedded, distributed, dialogic and explorative approach, where the dominating views and knowledge can be challenged and transformed. Sharing power, and embracing collectivity, provides foundations for responsible hope, whilst requiring that we too move away from our centres, and the traditionally hierarchical student–teacher relationship (Berglund and Verduijn Citation2018). Importantly, it makes relational learning, embedded in place, a likely candidate for novel and hopeful pedagogies (Larty Citation2021). By teaching entrepreneurship about, with, in and through place, and embedded in context, transformational ownership of personalized and grounded learnings can also promise wider freedoms, emancipation, and hope (Freire Citation1994 in Giroux, Citation2010).

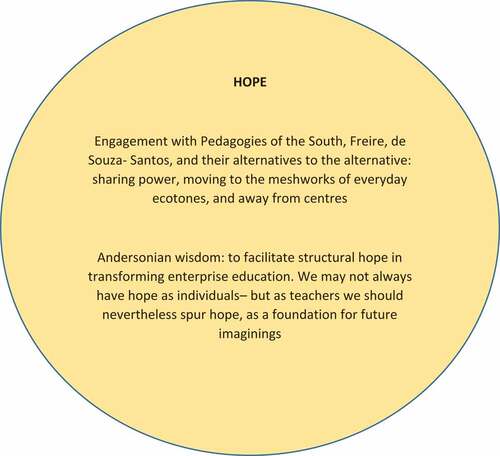

Hence, through our engagement with pedagogies of the south and Andersonian wisdom, we suggest that transformative enterprise education involves facilitating structural hope in just and sustainable futures, in re-imagining hopefully together, along ecotones edges and with everyday communities. Whilst it may be difficult to always be hopeful as individuals, as teachers we should nevertheless spur hope, although we may not have a clear idea of where to move or of potential solutions. Yet by socially just and environmentally sustainable transformation, structurally hopeful alternatives to our current crises may grow. We see our role as showing that there is an individually, collectively, and structurally hopeful position to take in facing unknown horizons; in finding alternatives to the alternative. brings together the insights we have drawn together here about hopeful transformation of enterprise education.

Transforming enterprise education through sustainability, social justice and hope

‘Entrepreneurship captures change, employs change and creates change as it forms new order, new organizations manifest as new business and new products from the vortex of change … change is clearly both the milieu and the medium for entrepreneurship’ (Anderson, Drakopoulou Dodd, and Jack Citation2012, 960).

We have argued for transforming enterprise education, and presented three guiding threads of what this might look like; sustainability, social justice, and hope. These are represented in Figure Four as overlapping fields, mutually supporting and reinforcing. This is, we hope, a helpful graphic summary of what transforming enterprise education might entail. However, a more evocative illustration of our argument might show the threads of sustainability, social justice and hope knotted together. Together, we argue, they form warps and wefts of our everyday enterprise meshworks, and thus the education we imagine transforming these connected ecotones.

Enterprise happens in flow, in the moment, as learning by doing, through the seams of the in-between and its ecotones. Transforming enterprise education builds on entrepreneuring-as-change, and enacts it within our educational programmes, interventions and classes. Our challenge is to build on this knowledge, and on these Andersonian wisdoms, in our class design, structure, delivery and assessment. Important questions for us all are those asking how transforming enterprise education (TrEE) can enhance student’s ability to deal with the uncertainty and messiness in their lives and societies. How can they become stronger, more ethical, more sustainable, more hopeful, more just and more aware decision makers and resource allocators? How can we help build learning communities skilled in wayfinding to and through transformed unknown futures, beyond the imposed dichotomies of centralized, economic, and abyssal thinking? For enterprise and entrepreneurship are less intentional straight roads to success, and more about journeying, co-creating bricolages, and making ways and meanings (Selden and Fletcher Citation2015).

Indeed, such pedagogical practices may make it possible to prepare our learners to embrace the unknown. A transformative pedagogy is interventionist in nature (e.g. Fenwick Citation2012). It is thus perhaps more action-oriented than critical pedagogy, whilst embracing its premises.

A transformative pedagogy suggests democratizing learning, and for teachers and students to position and reposition themselves, taking different positions in the meshwork? At the teachers’ side, there is choice, obviously, as suggested before. Teachers have the capacity to let go of traditional learning and teaching arrangements, broaden knowledge base(s), and make students co-responsible, and co-creators, of knowledge. Transformative pedagogy suggests that knowledge is being created in the process, not something ‘already-made’ that has to be ‘transmitted’ (Freire, Citation1970). So, a transformative pedagogy advocates participatory learning arrangements, the creating of communities of (co-) learners.

The core is about the ‘production of reflective practitioners’ as Jack and Anderson (Citation1999) suggested, enabling students to become better decision-makers (whether dealing with the planet, the social issues they face, or their own futures). This approach then does not view the students as objects for transferring knowledge or skills but places the students in the centre of the learning to transform the future by viewing the present in new ways (Verduijn and Berglund Citation2019). As such, it provides a possibility to re-think what other wor(l)ds we want to create. To learn from, with, and in diversity, we must share (new) knowledges and practices, and build relationality into our classes and their management.

Learning from Alistair, where do we move to next? Teacher exchanges, placements, and collaborations have arguably become much simpler to manage in a virtual world, and open us up to myriad new ways of thinking, teaching, and engaging. But of course, embracing a transformative pedagogy also means going to the margins, acknowledging thinking and knowing as relational activity (e.g. Braidotti Citation2019).

Conclusions

We have argued for the urgent need to re-position, to transform, enterprise education, just as Alistair Anderson helped re-position entrepreneurship theory. Underpinned by Epistemologies of the South, we have shown that transforming, socially just, hopeful, sustainable pedagogies are not only possible, but growing in number and variety. Those outlined here, for example, as Figure 4 illustrates, welcome diversity as a means to embracing the rights, agencies, and vulnerabilities of our planet’s human and non-human elements. In our crisis society, we have argued that hopefully responsible enterprise classes should and could be founded on an environmentally inclusive understanding of context, recognizing the biosphere as a fundamental good, which produces sustainably when nurtured. In the widest possible sense, our ecosystem models especially must be meeting a greater goal than the unfettered growth of one element – human economic capital, and, in this case, the human seeking to generate a living from their environment.

If enterprise, and its subgenre of entrepreneurship, are the names we give to the shaping of unknown future horizons, then we are perhaps uniquely positioned to make sense of these crises in-betweens, and to figure out how they may become a transformational landscape of hope. We enact these troubled terrains as thinkers, researchers, teachers, policy advisers, mentors, leaders, writers, consultants, trainers and human beings. Do we dare to enact them also as transformers? We hope here to have opened up the question of – if we choose to take on this responsibility – how might we work through theory to practice.

To provide direction for our journey, this essay brings to the surface just one of our major identities, roles, and practices, which also lie at the core of our profession and that is: teaching. Yet, we focus on transforming enterprise education very simply because it is with the enterprising makers of tomorrow that hopes of new futures rest. This aligns well with Alistair Anderson’s perspective about enterprise, in the form of entrepreneurship being an engine of change, a socio-economic process but one which realizes the moral obligation to do the right thing for society (Anderson Citation1995; Anderson, Jack and McKeever, Citation2015).

With this view of Alistair’s in mind, we have asked what we can do, most effectively, as entrepreneurship educators, to bring about the types of change which drove much of Alistair’s work, and to support all those seeking to learn the practices of transformative socio-economic engagement. How can we help our fellow citizens (whether or not they identify as entrepreneurs) to engage in ethical enterprise, in a moral way (Anderson Citation1995) to meet urgent needs, to keep sustainability and social justice in mind, and to dare to hopefully transform the unknown futures? Our answer is, as we hope this essay has shown, transforming enterprise education (TrEE) through hope, sustainability and social justice.

This paper draws from our wish to engage in collective reflexivity in re-thinking and re-imagining our values and teaching practices (Sklaveniti and Steyaert Citation2020). When we plan, deliver, evaluate, co-create our classes, we are acting, and being acted upon, in ways which fundamentally impact the ecosystems we both study, and are simultaneously embedded within. In this paper, we have elaborated on how enterprise education can be transformed, transforming and transformative, and argued for the ethical enactment of entrepreneurship through crises (Berglund, Hytti, and Verduijn Citation2020a, Citation2020b). We seek to provide ourselves with transforming directions and pedagogies by unlearning unsustainable practices (Braidotti Citation2019) and building on progressive practices of social justice (de Souza Santos, Citation2019), enabling us to remain hopeful in the face of the unknown (Freire Citation1994). Through this work, we engage with Alistair Anderson’s legacy; to creatively position and invoke entrepreneurship as a vehicle for positive and sustainable change. We see our support for this view as a conscious choice to move across its stepping stones, to follow its threads, from theory and research, into pedagogy, teaching and enterprise education. It is the rim of the wheel, not the hub, nor the spokes, where the traction happens. The margins, together, can turn the wheel too, can re-store, re-new, re-volve, re-volt. To be genuinely entrepreneurial scholars of entrepreneurship, as well as educators, we must be the agents of change we want to see in the world. It is not enough just to preach this to our students, or in our articles. Let us instead do what the in-between does best, and foster a collective, bricolaged, hopeful re-volution. It is our wheel to turn, after all.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Clearly this essay is a collective act of memory, grief, love, of many imagined conversations with Alistair, who was very much with us on this journey. We discovered hidden and forgotten gems, too, and they helped us move from a position of rage and despair, to one of hope in transformation. We thank him for this, as for so much else, but, above all, his friendship. You are so, so missed, dear friend.

2. We have chosen to use the broader concept of ‘enterprise education’ throughout, to engage with as wide a landscape as possible in this exploratory essay. ‘Entrepreneurship education’ is a subset, although a large one, of this wider pedagogical field.

References

- Anderson, A.R. (1995). “The Arcadian Enterprise: an enquiry into the nature and conditions of rural small business.” PhD. Stirling University.

- Anderson, A. R. 1998. “Cultivating the Garden of Eden: Environmental Entrepreneuring.” Journal of Organizational Change Management 11 (2): 135–144. doi:10.1108/09534819810212124.

- Anderson, A. R. 2000. “Paradox in the Periphery: An Entrepreneurial Reconception.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 12 (2): 91–110. doi:10.1080/089856200283027.

- Anderson, Alistair R, and Sarah L Jack. 2008. “Role Typologies for Enterprising Education: The Professional Artisan?.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development.

- Anderson, A.R., S. Drakopoulou Dodd, and S.L. Jack. 2012. “Entrepreneurship as Connecting: Some Implications for Theorising and Practice.” Management Decision 50 (5): 958–971. doi:10.1108/00251741211227708.

- Anderson, A.R., and J. Gaddefors. 2016. “Entrepreneurship as a Community Phenomenon; Reconnecting Meanings and Place.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 28 (4): 504–518. doi:10.1504/IJESB.2016.077576.

- Andreotti, V.D.O., S. Stein, K. Pashby, and M. Nicolson. 2016. “Social Cartographies as Performative Devices in Research on Higher Education.” Higher Education Research & Development 35 (1): 84–99. doi:10.1080/07294360.2015.1125857.

- Bensemann, Jo, Lorraine Warren, and Alistair Anderson. 2021. “Entrepreneurial Engagement in a Depleted Small Town: Legitimacy and Embeddedness.” Journal of Management & Organization 27 (2): 253–269.

- Berglund, K., J. Gaddefors, and M. Lindgren. 2015. “Provoking Identities: Entrepreneurship and Emerging Identity Positions in Rural Development.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 28 (1–2): 76–96. doi:10.1080/08985626.2015.1109002.

- Berglund, K., M. Lindgren, and J. Packendorff. 2017. “Responsibilising the Next Generation: Fostering the Enterprising Self through de-mobilising Gender.” Organization 24 (6): 892–915. doi:10.1177/1350508417697379.

- Berglund, K., and K. Verduijn, Eds. 2018. Revitalizing Entrepreneurship Education: Adopting a Critical Approach in the Classroom. Oxon: Routledge.

- Berglund, K., U. Hytti, and K. Verduijn. 2020a. “Unsettling Entrepreneurship Education.” Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 3 (3): 208–213. doi:10.1177/2515127420921480.

- Berglund, K., U. Hytti, and K. Verduijn. 2020b. “Navigating the Terrain of Entrepreneurship Education in Neoliberal Societies.” Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 4.702–717

- Braidotti, R. 2019. Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Brunila, Kristiina ”From risk to resilience: The therapeutic ethos in youth education.” Education Inquiry 3, no. 3 (2012): 451–464.

- Darder, A. 2017. Reinventing Paulo Freire: A Pedagogy of Love. England. Routledge.

- de Sousa Santos and Maria Paula Meneses. 2019. Knowledges Born in the Struggle: Constructing the Epistemologies of the Global South. Oxford: Routledge.

- Dodd, S., A. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2021. “Let Them Not Make Me a Stone”—repositioning Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Small Business Management 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1867734

- Fenwick, T. 2012. “Matterings of Knowing and Doing: Sociomaterial Approaches to Understanding Practice.” In Practice, Learning and Change, edited by L. Hager and Reich, 67–83. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Freire, Paulo. 1970. “Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York.” Continuum 72: 43–70.

- Freire, P. 1994. Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Gaddefors, J., and A. Anderson. 2017. “Entrepreneurship and Context: When Entrepreneurship Is Greater than Entrepreneurs.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior and Research 23 (2): 267–278. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-01-2016-0040.

- Gaddefors, J., and A. Anderson. 2018. “Context Matters: Entrepreneurial Energy in the Revival of Place.” In Creating Entrepreneurial Space: Talking through Multi-Voices, Reflections on Emerging Debates (Contemporary Issues in Entrepreneurship Research, edited by D. Higgins, P. Jones, and P. McGowan, 63–78. Vol. 9A. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/S2040-72462018000009A004.

- Gaggiotti, H., C. Jarvis, and J. Richards. 2020. “The Texture of Entrepreneurship Programs: Revisiting Experiential Entrepreneurship Education through the Lens of the liminal–liminoid Continuum.” Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy 3 (3): 236–264. doi:10.1177/2515127419890341.

- Galloway, Laura, and Wendy Brown. 2002. “Entrepreneurship Education at University: A Driver in the Creation of High Growth Firms?.” Education+ Training.

- Gennep, Arnaold van. 1960. ”The Rites of Passage.”. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Gibb, Allan. 2002. “In Pursuit of a New ‘Enterprise’And ‘Entrepreneurship’Paradigm for Learning: Creative Destruction, New Values, New Ways of Doing Things and New Combinations of Knowledge.” International Journal of Management Reviews 4 (3): 233–269.

- Giroux, Henry a. 2010. “Rethinking Education as the Practice of Freedom: Paulo Freire and the Promise of Critical Pedagogy.” Policy Futures in Education 8 (6): 715–721.

- Heikkurinen, P., S. Clegg, A.H. Pinnington, K. Nicolopoulou, and J.M. Alcaraz. 2019. “Managing the Anthropocene: Relational Agency and Power to Respect Planetary Boundaries.” Organization & Environment, 34. 1086026619881145.

- Hermann, R. R., and M. B. Bossle. 2020. “Bringing an Entrepreneurial Focus to Sustainability Education: A Teaching Framework Based on Content Analysis.” Journal of Cleaner Production 246: 119038. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119038.

- Hjorth, D., and C. Steyaert. 2004. “Narrative and Discursive Approaches in Entrepreneurship: A Second Movements in Entrepreneurship Book.” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

- Hjorth, D., and C. Steyaert, eds. 2010. The Politics and Aesthetics of Entrepreneurship: A Fourth Movements in Entrepreneurship Book. Edward Elgar Publishing; UK

- hooks, bell. 2003. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. New York: Routledge.

- Imas, J. M., N. Wilson, and A. Weston. 2012. “Barefoot Entrepreneurs.” Organization 19 (5): 563–585. doi:10.1177/1350508412459996.

- Ingold, T. 2008. “Bindings against Boundaries: Entanglements of Life in an Open Orld.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (8): 1796–1810. doi:10.1068/a40156.

- Jack, S.L., and A.R. Anderson. 1999. “Entrepreneurship Education within the Enterprise Culture: Producing Reflective Practitioners.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 5 (3): 110–125. doi:10.1108/13552559910284074.

- Jack, S.L., and A.R. Anderson. 2002. “The Effects of Embeddedness upon the Entrepreneurial Process.” Journal of Business Venturing 17: 467–487. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00076-3.

- Johnsen, Christian Garmann, Lena Olaison, and Bent Meier Sørensen. 2018. “Conceptual Activism: Entrepreneurship Education as a Philosophical Project.” In Revitalizing Entrepreneurship Education, pp. 119–136. Routledge.

- Johnston, Julie. 2009. “Transformative Environmental Education: Stepping outside the Curriculum Box.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 14 (1): 149–157.

- Kibler, E., M. Fink, R. Lang, and P. Muñoz. 2015. “Place Attachment and Social Legitimacy: Revisiting the Sustainable Entrepreneurship Journey.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 3: 24–29. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2015.04.001.

- Korsgaard, S., A. Anderson, and J. Gaddefors. 2016. “Entrepreneurship as re-sourcing: Towards a New Image of Entrepreneurship in a Time of Financial, Economic and socio-spatial Crisis.” Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy 10 (2): 178–202. doi:10.1108/JEC-03-2014-0002.

- Kuckertz, Andreas. ”Let's take the entrepreneurial ecosystem metaphor seriously!.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 11 (2019): e00124.

- Larty, J. 2021. “Towards a Framework for Integrating place-based Approaches in Entrepreneurship Education.” Industry and Higher Education, 35. 09504222211021531.

- Lepistö, T. T., and U. Hytti. 2020. “Developing an Executive Learning Community: Focus on Collective Creation.” Academy of Management Learning & Education. doi:10.5465/amle.2018.0338.

- Loureiro, C. F., and J. R. Torres.2014.Educação Ambiental - dialogando com Paulo Freire.São Paulo: Cortez. orgs.

- McKeever, E., A. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2014. “Entrepreneurship and Mutuality: Social Capital in Processes and Practices.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (5–6): 453–477. doi:10.1080/08985626.2014.939536.

- McKeever, E., S. Jack, and A. Anderson. 2015. “Embedded Entrepreneurship in the Creative re-construction of Place.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (1): 50–65. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.002.

- Pansera, M., and M. Fressoli. 2020. “Innovation without Growth: Frameworks for Understanding Technological Change in a post-growth Era.” Organization 28. 1–25.

- Paulo Freire Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30Th Anniversary. 2000. New York-London: Continnum.

- Paulo Freire, J. Fraser, D. Macedo, T. McKinnon, and W. Stokes, edited by. 1997. “A Response.” In Mentoring the Mentor: A Critical Dialogue with Paulo Freire. New York: Peter Lang.

- Quijano, A. 2005. “The Challenge of the “Indigenous Movement” in Latin America.” Socialism and Democracy 19 (3): 55–78. doi:10.1080/08854300500258011.

- Rodríguez-Romero, M. 2020. ““Investigación Educativa, Neoliberalismo Y Crisis Ecosocial. Del Extractivismo a la Reciprocidad Profunda” [Educational Research, Neoliberalism and Eco-Social Crisis. From Extractivism to Deep Reciprocity].” Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación 18 (2): 135–149. doi:10.15366/reice2020.18.2.007.

- Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2003. “The World Social Forum: Toward a Counter-Hegemonic Globalization.” Ponencia Presentada Al XXIV Congreso Internacional de la Asociación de Estudios Latinoamericanos, LASA. Dallas. Marzo 27–29.

- Santos B. D. S.2016. “Epistemologies of the South and the Future.” From the European South 1: 17–29.

- Santos B.de, S. 2014. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicede. Boulder (Colorado): Paradigm.

- Sarah, Drakopoulou Dodd, Alistair R Anderson. ”Mumpsimus and the Mything of the Individualistic Entrepreneur.” International Small Business Journal 25, no. 4 (2007): 341–360.

- Selden, P. D., and D. E. Fletcher. 2015. “The Entrepreneurial Journey as an Emergent Hierarchical System of artifact-creating Processes.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (4): 603–615. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.09.002.

- Shrivastava, P., and J.J. Kennelly. 2013. “Sustainability and place-based Enterprise.” Organization & Environment 26 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1177/1086026612475068.

- Sklaveniti, C., and C. Steyaert. 2020. “Reflecting with Pierre Bourdieu: Towards a Reflexive Outlook for practice-based Studies of Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 32 (3–4): 313–333. doi:10.1080/08985626.2019.1641976.

- Steyaert, C., and D. Hjorth, eds. 2008. Entrepreneurship as Social Change: A Third New Movements in Entrepreneurship Book. Vol. 3. Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham

- Torres‐Santomé, J. 2018. “Educating Mathematizable, Self‐Serving, God‐Fearing, Self‐Made Entrepreneurs.” The Wiley Handbook of Global Educational Reform 17. 351–370.

- Tozoni-Reis, M. F. C. 2006. “Temas Ambientais Como “Temas Geradores”: Contribuições Para Uma Metodologia Educativa Ambiental Crítica, Transformadora E Emancipatória.” Educar em Revista (27): [ online]. [Access 23rd August 2021]. 93–110. doi:10.1590/S0104-40602006000100007.

- Turner, Victor. 1967. “Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites de Passage.” The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual 93: 111.

- Valentine, J (2019) “Neo-liberalism and the New Institutional Politics of Universities.” Jimmy Reid Foundation, Glasgow, May 2019 https://reidfoundation.scot/2019/05/neo-liberalism-and-the-new-institutional-politics-of-universities-paper-now-available/

- Verduijn, K., and K. Berglund. 2019. “Pedagogical Invention in Entrepreneurship Education.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 26 (5): 973–988. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-04-2018-0274.

- Wahl, D. Ch. 2019. “Gaia Education’s Resources for Creating Multipliers of Local SDG Implementation.” Sustainability: The Journal of Record 12: 134–139. doi:10.1089/sus.2019.29155. April 2019.

- Welter, F., and T. Baker. 2020. “Moving Contexts onto New Roads: Clues from Other Disciplines.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 45, 1042258720930996.