ABSTRACT

This research examines the formation and development processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs in the context of institutional logics change in an emerging economy. Building on the microfoundations lens and the institutional logics perspective, the empirical investigation focuses on the qualitative study of the interfirm collaborative relationships among SMEs in China. The research findings underscore the significant role played by government-supported broker firms in fostering the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs. In particular, these broker firms first reproduce the institutional logics by means of championing government-promoted projects and events and diffusing government policies through their sensemaking and sensegiving. The reproduction of institutional logics by broker firms facilitates the formation and development processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs which, over time, may lead to collaboration success occurrences that are predominantly manifested by success events, artefacts and stories. In the case of new meanings emergent from the collaboration success occurrences, broker firms tend to engage in legitimating these new meanings to transform the institutional logics. Thereby, this research contributes to the theoretical advancement in the fields of inter-organizational collaborations among SMEs and institutional logics.

Introduction

Interfirm collaboration among small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has received increasing attention from entrepreneurship and management scholars, industry practitioners and policymakers. SMEs often collaborate with one another in industrial clusters and districts (Bianchi Citation1993; Porter Citation1990; Scott, Hughes, and Kraus Citation2019; Vernay, D’Ippolito, and Pinkse Citation2018) where governments establish incubators to encourage regional entrepreneurship (Bliemel et al. Citation2019; Wang and Liu Citation2016; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018), SME innovation (Hemmert Citation2019; Phillips, Lawrence, and Hardy Citation2000; Verdú and Tierno Citation2019; Zeng, Xie, and Tam Citation2010), and internationalization (Libaers and Meyer Citation2011; Liu Citation2017; Rosenbaum, Madsen, and Johanning Citation2019; Smallbone and Welter Citation2012). The collaborative relationships among SMEs may take manifold forms such as supply chain and service agreements, strategic partnerships, and alliances (Reuer, Matusik, and Jones Citation2019). It has been widely recognized that interfirm collaboration in industrial clusters can contribute to SMEs’ value creation and improved performance (Oviatt and McDougall Citation1994; Porter Citation1990; Reuer, Matusik, and Jones Citation2019; Zacharakis Citation1997) by increasing the possibility for new market access, resource acquisition, technology development, and collective learning (Huggins Citation2000; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021; Ryan et al. Citation2019; Staber Citation2009; Zeng, Xie, and Tam Citation2010).

Extant studies often focus on the interfirm collaborative relationships that have already been established by SMEs and look at the effect of interfirm collaboration upon SMEs’ internationalization, value creation and/or performance (Hemmert Citation2019; Ryan et al. Citation2019; Zeng, Xie, and Tam Citation2010). For instance, based on the research investigation of born global firms in the Irish animation sector, Ryan et al. (Citation2019) conclude that SMEs can utilize their existing high-intensive interfirm collaborative relationships for accelerated international market entry and growth. Zeng, Xie, and Tam (Citation2010) examine the relationship between interfirm collaboration and innovation performance of SMEs. Their findings suggest that both vertical and horizontal collaboration with customers, suppliers and other firms play a distinct role in SMEs’ innovation performance (ibid).

However, less is known about how interfirm collaboration among SMEs comes into being in the first place and how such collaborative relationships develop over time. These are essential process questions surrounding the development of interfirm collaborative relationships (Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994; Van de Ven Citation1976). Despite the increasing scholarly attention to SMEs’ interfirm collaboration, there is still a lack of microscopic and nuanced mechanisms to unfold the interfirm collaborative relationships among SMEs from the institutional logics perspective (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Thornton and Ocasio Citation2008).

Institutional logics (Friedland and Alford Citation1991; Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999), as a manifestation of the microfoundations lens (Contractor et al. Citation2019), have been regarded as a promising theoretical perspective for the studies of entrepreneurship (Greenman Citation2013; Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018) and inter-organizational collaboration (Ahmadsimab and Chowdhury Citation2021; Nicholls and Huybrechts Citation2016; Saz-Carranza and Longo Citation2012). As important institutional actors (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018), government and government-related agencies have increasingly promoted interfirm collaboration activities among SMEs – for example, in technology-intensive industries – in their regional policies to boost economic growth (Casson and Giusta Citation2007; Liang and Liu Citation2018; Vernay, D’Ippolito, and Pinkse Citation2018). These regional policies can be regarded as macro level institutional logics that shape the behaviour of SMEs and their firm members. Due to the contextual factors, institutional logics in non-western regions do not necessarily entail the same pattern of interplay between society, organizations, and individuals (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012). In non-western contexts, only a few studies have examined the influence of institutional logics on the behaviours of firms and firm members (Jain and Sharma Citation2013; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). These studies suggest that emerging economies may ‘challenge theories developed to explain phenomena occurring in relatively stable and mature economies’ (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018, 671). Thus, emerging economies, such as ‘the current transformation of China’, offer ‘a natural, real-time laboratory’ (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012, 174) to contribute to theoretical advancement (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018).

Building on the microfoundations lens (Contractor et al. Citation2019) especially the institutional logics perspective (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Thornton and Ocasio Citation2008), this study aims to investigate the formation and development processes of interfirm collaborative relationships among SMEs during the process of institutional logics transformation in China. There has been little research conducted on the micro processes of reproducing and transforming institutional logics at the levels of firms and individuals involved in interfirm collaboration. To fill this theoretical gap, a qualitative study was conducted to examine how the social actors of SME members reproduce and transform institutional logics in fostering regional interfirm collaboration. Thus, the research question is formulated as: How do SME firm members form and develop interfirm collaboration in the context of institutional logics change in an emerging economy?

This research focuses on a qualitative study of the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs in the light of institutional logics change in China. There are two reasons for conducting the research qualitatively. First, the choice of a qualitative research approach is determined by the exploratory nature of the research question (Crick Citation2021; Welch et al. Citation2011) and the contextual features in relation to emerging economies (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). Second, the qualitative approach has a unique advantage for offering micro level analysis without necessarily losing its overall, macro coherence with regard to institutional logics (Greenman Citation2013; Lok Citation2010).

The research findings reveal the significant role played by government-supported broker firms in fostering the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs. These broker firms first reproduce the institutional logics advocated by the central and regional governments through championing government-promoted projects and/or events and diffusing government policies through their sensemaking and sensegiving. The reproduction of institutional logics by broker firms facilitates the formation and development processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs. The processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs, over time, may lead to collaboration success occurrences which are predominantly manifested by success events, artefacts and stories. These collaboration success occurrences are then distributed by the community of SMEs, broker firms, governments, and goverment agencies. In the case of new meanings emergent from the collaboration success occurrences, broker firms often engage in legitimating these new meanings to transform the institutional logics.

This research contributes to the growing body of research on interfirm collaboration among SMEs and institutional logics in three ways. First, this research demonstrates that the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs can be mediated and supported by a broker firm that often runs the incubation centres sponsored by governments. The broker firm is a private firm that builds partnerships with governments to reproduce societal level institutional logics (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012) in their supporting activities to nurture the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs (Huggins Citation2000). Second, this research explicates the detailed mechanisms employed by the broker firm in the reproduction and transformation of institutional logics and sheds light on the extant theorization of institutional logics in inter-organizational collaboration among SMEs based in emerging markets (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). Third, this research unfolds the processual dynamics of forming and developing interfirm collaboration among SMEs through a qualitative research design (Welch et al. Citation2011). By doing this, this research contributes to the process research on inter-organizational relationships (Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994; Van de Ven and Huber Citation1990; Zhang and Huxham Citation2009, Citation2020).

The paper begins by reviewing the literature on institutional logics and interfirm collaboration among SMEs. How the research was conducted empirically is presented next, which includes the research context, data collection and analysis methods. This is followed by the discussion of the empirical findings. The paper is concluded with theoretical and policy implications.

Theoretical background

Interfirm collaboration among SMEs from a microfoundations lens

Interfirm collaborationFootnote1 involves firm members’ working across firm boundaries towards some positive end (Huxham and Vangen Citation2005; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021). There are manifold forms of interfirm collaboration employed by SMEs in their development and foreign market entry, such as supply chain and distributor relationships, joint ventures, strategic alliances and partnerships (Festing, Schäfer, and Scullion Citation2013; Liu Citation2017; Liu and Almor Citation2016; Ryan et al. Citation2019; Smallbone and Welter Citation2012). The importance of interfirm collaboration has long been recognized in entrepreneurship and management studies (Huggins Citation2000; Huggins and Johnston Citation2010; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021). For instance, Festing, Schäfer, and Scullion (Citation2013) conducted a study of seven hundred German SMEs and identified that collaborative partnership among SMEs can help them cope with talent management in order to alleviate resource deficiency. Based on the study of knowledge-intensive born global firms, Liu (Citation2017) highlights that interfirm partnerships with overseas distributors can facilitate born global firms to acquire needed resources and manage uncertainty in foreign markets. Similarly, Ryan et al. (Citation2019) emphasize the importance of collaborative relationships among born global firms in a local horizontal network for their accelerated acquisition of foreign market knowledge and global customers. Although the significance of interfirm collaborative relationships is widely recognized in these studies, less is known about how such interfirm collaborative relationships form and evolve in the course of SME development and international expansion.

The process approach to interfirm collaboration among SMEs centres on the answer of how and why questions in relation to inter-organizational relationships (Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994; Van de Ven Citation1976). Instead of treating process as a variable, process research examines ‘events, activities, and choices as they emerge and sequence themselves over time’ (Bizzi and Langley Citation2012, 225). Such process theorizing is essential for entrepreneurship and management studies because of its explicit focus on temporal patterning of events which has been largely underplayed in variance models (Langley Citation2009; Van de Ven and Huber Citation1990). Given the importance of process research in interfirm collaboration, there is still a lack of attention to the formation and development of the interfirm collaborative relationship among firm members and the effect of such individual and organizational level collaboration upon the institutional environment (Foss Citation2011; Greenman Citation2013; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021).

A microfoundations lens (Barney and Felin Citation2013; Contractor et al. Citation2019; Felin et al. Citation2012; Foss Citation2011) has been regarded as an important theoretical foundation for the investigation of interfirm collaboration (Liu et al. Citation2017; Mueller Citation2021). A microfoundations lens concerns a set of heuristics around theory building which seeks ‘causal explanations for firm-level characteristics and strategies’ on the basis of ‘the characteristic predilections, actions and interactions of organizational members’ (Contractor et al. Citation2019, 5). As Barney and Felin (Citation2013, 145) argue, ‘organizational analysis should be fundamentally concerned with how individual level factors aggregate to the collective level’. Such a microfoundations lens makes it possible to examine the interfirm collaborative interaction at the level of individuals and link it with meso- (organizational) and macro- (institutional) level outcomes (Liu et al. Citation2017; Mueller Citation2021). Despite its importance, the microfoundations lens has predominantly informed research in single organizations, with less attention to interfirm collaborations especially among SMEs.

Drawing upon the microfoundations lens and network theory, Mueller (Citation2021) develops a conceptual model that explains how the behavioural antecedents of network facilitators – who manage the collaboration among network firms – are linked with their facilitation practices and positive network level outcomes. This conceptual model emphasizes the role of network facilitators in nurturing trust among collaborating organizations even though there is no distinction given in association with the size or type of the collaborating organizations researched; for instance, whether the researched organizations are SMEs, multinational corporations or social enterprises. Such contextual features of the collaborating organizations matter because they contribute to theory building and explanation (Reuber and Fischer Citation2022; Welch et al. Citation2011). In an editorial article on the investigation of human side factors as the microfoundations of inter-organizational collaboration, Liu (Citation2017, 157) call for future research to pay more attention to ‘the role of context’ and to the ‘specifics of emerging economies’ in particular.

Institutional logics in interfirm collaboration among SMEs

Institutional logics, as a theoretical perspective which builds on the microfoundations lens (Contractor et al. Citation2019), has received increasing attention from entrepreneurship and management scholars researching interfirm collaboration or broader inter-organizational collaboration (see, for example, Ahmadsimab and Chowdhury Citation2021; Jain and Sharma Citation2013; Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018; Nicholls and Huybrechts Citation2016; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). Institutional logics are defined as overarching, socially constructed assumptions, values, beliefs and principles by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their material subsistence (Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999, Citation2008). They are connected with macro level institutional orders (Friedland and Alford Citation1991) such as state, market, profession, and corporation (Greenman Citation2013; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012).

Extant studies on institutional logics in the entrepreneurship and management fields have largely focussed on the western context (Greenman Citation2013; Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018). For example, based on a qualitative study of Finnish and French SME collaborating partners, Leppäaho and Pajunen (Citation2018) explore how SMEs adapt to differences in institutional logics in their networking when they enter an institutionally distant market. Their findings indicate that cross-border interfirm collaboration activities are influenced by institutionally prescribed logics of behaviour (i.e. Finnish and French cultural norms and values), which may lead to SME conflicts or misunderstandings in a foreign context even when that context is geographically close. Greenman (Citation2013) examines the relationship between institutional logics and everyday entrepreneurial action through an ethnographic study of micro and small enterprise owner-founders in the creative industries based in the UK. The research findings reveal that institutional logics can be used to explore the ‘symbolic grammars’ of entrepreneurial action and various institutional logics exist in a ‘cultural context’ and exert influence over everyday entrepreneurial action (Greenman Citation2013, 643). Greenman (Citation2013) argues that such a cultural context can be firmly integrated into entrepreneurship theory development. However, it is not clear whether the interplay between society, organizations, and individuals entails the same pattern across the western and non-western cultural context such as emerging economies (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012).

Emerging economies, which are defined as ‘low-income, rapid-growth countries using economic liberalization as their primary engine of growth’ (Hoskisson et al. Citation2000, 249), can offer a real-time laboratory context for theoretical advancement on institutional logics from the societal level to the organizational and individual level (Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). On the one hand, economic liberalization implies that national governments initiate and implement policy changes to boost economic growth. Among these national policies, industrial clusters and incubation centres are often favourably adopted by governments to encourage co-located firms, many of which are SMEs, to gain synergies and attain competitive advantage (Porter Citation1990). These national policies can be seen as societal level institutional logics that shape the organizational and individual behaviour. However, on the other hand, agency exists, which allows institutional entrepreneurship to emerge and form collective identity and legitimacy (Kalantaridis and Fletcher Citation2012; Phillips, Lawrence, and Hardy Citation2000; Wry, Lounsbury, and Glynn Citation2011) that may complement or challenge the existing institutional logics. Xing, Liu, and Cooper (Citation2018) conduct research on public-private collaborative partnerships initiated by Chinese regional government, who were deemed as institutional entrepreneurs, with private firms led by overseas returnee entrepreneurs, in order to promote regional entrepreneurship. They call for future research that examines other social actors in collaboration as the pattern of collaborative relationships may differ. This study responds to Xing, Liu, and Cooper’s (Citation2018) call by investigating how the social actors of SMEs and individuals involved form and develop interfirm collaboration in the context of institutional logics change in an emerging economy context.

Research methodology

In order to provide a deeper understanding of the dynamics of interfirm collaboration among SMEs, this study embraced qualitative-constructivist methodology (Lok Citation2010) and adopted discovery-driven research methods (Locke Citation2011). A multi-method approach (Vaara and Monin Citation2010) was employed, which comprised of case studies (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018), semi-structured interviews (Silverman Citation1993), observations (Junker Citation2004) that were conducted at major SME conferences and collaboration events, and content analysis (Corley and Gioia Citation2004) of both primary data and secondary archival data. This multi-method approach gave rise to the collection of different types of qualitative data from a wide range of sources for inductive and abductive theory-building (Fisher and Aguinis Citation2017; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013; Welch et al. Citation2011).

Research context

The creative industry SME cluster situated in Shenzhen was chosen as the research context for three reasons. First, Shenzhen, as a special economic zone and one of the most developed cities in China, has been designated as a national pilot city for comprehensive reform. This becomes a valuable context for studying institutional logics transformation because new institutional logics are often first introduced in Shenzhen before being diffused in other cities in China. Second, Shenzhen is one of the top cities for entrepreneurship in China, providing favourable policies for SME development and collaboration. Third, the city of Shenzhen was appointed as a City of Design by UNESCO in 2008 and is now a member of the Creative Cities Network (UNESCO Citation2019). Shenzhen has more than 6,000 creative design firms (UNESCO Citation2019), many of which are SMEs co-locating in geographically proximate clusters. Such creative SME clustering offers a promising context for examining SME interfirm collaborative relationships and for the theoretical advancement and empirical refinement of entrepreneurship and management studies (Greenman Citation2013; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018).

In particular, the empirical fieldwork was conducted in the F518 Idea Land Industrial Park (subsequently referred to as F518 Park) in the Bao’an District of Shenzhen, China. The F518 Park, housing more than 600 SMEs, was run by Shenzhen Creative Investment Company (subsequently referred to as Shenzhen-CreativeCo) that was also an SME. In 2015, Shenzhen Municipal Government of China and Edinburgh City Council of the UK established the Edinburgh-Shenzhen Creative Exchange (ESCE) collaborative project, which provided incubator space and support for the creative SMEs from each city. Two incubation centres were established for the ESCE collaborative project with one based in the F518 Park, Shenzhen, China and the other based inside the building of Edinburgh City Council, Edinburgh, UK. This ESCE collaborative project was championed by Shenzhen-CreativeCo and supported by both Shenzhen and Edinburgh municipal governments. This research examined the interfirm collaborative relationships among Shenzhen-CreativeCo and other SMEs that were either located in the F518 Park or associated with the ESCE collaborative project.

Data collection

Based on the theoretical sampling method (Eisenhardt, Graebner, and Sonenshein Citation2016; Suddaby Citation2006), primary data were collected mainly through the author’s professional networks and contacts. The field investigation spanned from June 2018 to July 2019 and consisted of two rounds of intensive data collection. The first round (R1) took place in June and July 2018 and the second round (R2) took place in June and July 2019. The data collected were in the form of semi-structured interviews, observation of events and conferences, tours of the firms involved in the research, and archival documents (e.g. reports, news articles, and media coverage of SMEs and governments). Thirty-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with informants, including senior management teams from eight SMEs located in the F518 Park, government officials from China and the UK, and a consulting company that provided services to SMEs for their interfirm collaboration and internationalization. The interview participants were chosen by including the key stakeholders who contributed to interfirm collaboration among SMEs. Therefore, the selection of samples deliberately focused on government officials, SME managers, and associated consulting companies. Because the analytical focus of the study was SME interfirm collaboration in the context of institutional logics change, particular attention was paid to the interaction and collaborative activities among SME partners and the associated stakeholders such as consulting company members and government officials. This balanced approach to data collection led to the attainment of multiple and complementary perspectives on the research question (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). presents an overview of the primary interview data, showing the distribution and working position of the interview participants.

Table 1. Primary interview participants.

The interviews, which lasted between 50 and 110 minutes, were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Yin’s (Citation1994) guidelines were followed in the development of the interview questions to make them as non-leading as possible. In both rounds (R1 and R2) of data collection, at the beginning of each interview, neutral and non-threatening questions were asked to build a relationship of mutual trust (Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018). These opening questions involved the interview participant’s job title, duration of working in the researched organization, and working duties. Then the interview participants were asked to describe their organizations in general and, thereafter, the institutional contexts as well as the interfirm collaboration activities in which they were engaged. In particular, these questions concerned the collaborative relationships among SMEs, the kind of institutional contexts these collaborative relationships are situated in, how they are formed and developed, whether any challenges are encountered and how interview participants respond to these challenges.

In addition to the semi-structured interviews, notes and diaries were kept for the observations made during the author's visit to the firm premises and attendance at two major conference events organized for SME interfirm collaboration and internationalization. Moreover, secondary data were gathered in the form of archival documents including central and regional government policy documents and promotional materials, company reports, newsletters, newspaper and media coverage, and websites. These archival data helped to triangulate the insights gleaned from the semi-structured interviews and observations (Crick Citation2021; Patvardhan, Gioia, and Hamilton Citation2015). The primary data collection ended when additional interviews, observations and archival documents ceased to generate significant new information and insights in relation to the research question (Crick Citation2021; Suddaby Citation2006).

Data analysis

Content analysis was conducted for the data gathered from interviews, observation note-taking, and archival documents by following the inductive and abductive theory building approach (Fisher and Aguinis Citation2017; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013; Patvardhan, Gioia, and Hamilton Citation2015; Welch et al. Citation2011). First, the analysis was commenced by using open coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation2008) of the interview transcripts and observation notes to identify first-order codes (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013), typically beginning with interview participants’ descriptions of the SME interfirm collaboration activities that they initiated and/or attended and the institutional contexts in which these interfirm collaboration activities were embedded. Both ‘In vivo’ labels – which are the terms actually used by informants – and researcher ‘assigned’ labels were used to preserve ‘informant-level meanings’ (Patvardhan, Gioia, and Hamilton Citation2015, 411). Constant comparative methods (ibid) were adopted to compare and contrast the data gathered from the first and second round and across interview participants and sources to ensure the analytic distinction of each code generated.

The first-order coding was followed by axial coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation2008) that involves the synthesis of the first-order codes into more abstract, second-order themes (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). Axial coding was conducted by moving back and forth between the data and the relevant literature on microfoundations perspectives, institutional logics, and interfirm collaboration among SMEs. After successive iterations between data and literature, the second-order themes were generated around broker practice for reproducing and transforming institutional logics, formation and development of SME interfirm collaboration and collaboration success. To illustrate the second-order concepts, quotations were used from the interview transcripts, observation notes and archival documents. Occasionally some details have been concealed or given pseudonyms for confidentiality purposes.

Then theoretical coding (Patvardhan, Gioia, and Hamilton Citation2015) was carried out which involves assessing the semantic relationships among the second-order themes. This coding practice engendered the aggregation of the second-order themes into three theoretical dimensions that explain how collaborating firm members and associated broker firm members engaged in SME interfirm collaboration to reproduce and transform the institutional logics. In detail, these aggregated theoretical dimensions are: (1) reproduction of institutional logics; (2) processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs; and, (3) transformation of institutional logics. presents the data analysis process by displaying the data structure, first-order coding, second-order coding, and aggregated theoretical dimensions. Triangulation of the primary data with secondary archival data was employed in the analysis to strengthen the interpretation of the interview and observation data and enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the research findings (Crick Citation2021; Ryan et al. Citation2019).

Findings

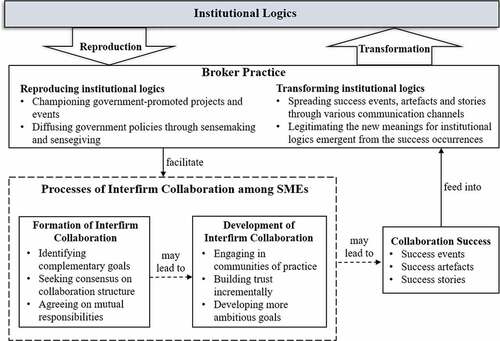

The empirical analysis suggests the significant role played by government-supported broker firms in fostering the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs. These broker firms first reproduce the institutional logics advocated by the central and regional governments by means of championing government-promoted projects and events and diffusing government policies through their sensemaking and sensegiving. The reproduction of institutional logics by broker firms facilitates the processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs. Such processes involve both the formation and development of interfirm collaboration. In the formation process, broker firm members actively engage in identifying suitable collaborating partners and facilitating SME partners’ identification of complementary goals, consensus seeking on collaboration structure, and agreement-building on mutual responsibilities. In the development process, broker firm members also champion activities, conferences and events to bring SME partners together to engage in communities of practice. These facilitation activities form grounds for SME partners to build trust incrementally and develop more ambitious goals for their interfirm collaboration. The processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs, over time, may lead to collaboration success occurrences that are predominantly manifested by success events, artefacts and stories. These collaboration success occurrences are then distributed by the community of SMEs, broker firms, governments, and government agencies. In the case of new meanings emergent from collaboration success occurrences, broker firms often engage in legitimating these new meanings to transform the institutional logics. presents a conceptual framework that was developed to illuminate the processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs in the context of institutional logics change and the significant role of broker practice. In the following elaboration of the conceptual framework, the term ‘partner’ is used to refer to collaboration firm and ‘participant/member’ to refer to individuals who engage in interfirm collaborations.

Figure 2. A conceptual framework of interfirm collaboration processes among SMEs in the context of institutional logics change.

Broker practice: reproducing institutional logics

The research analysis identified the precursor role played by broker firms with two distinctive forms of practice in fostering the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs: championing government-promoted projects and events and diffusing government policies through sensemaking and sensegiving. The critical events were traced in relation to the Edinburgh-Shenzhen Creative Exchange from 2013 to 2019 and were used as a basis for building a narrative account of how broker firms reproduce institutional logics in their everyday practice.

Championing government-promoted projects and events

Championing government-promoted projects and events involves taking a lead in organizing and managing projects and activities endorsed by the government. In the case of China, there were new government initiatives promoted in the policy document entitled ‘China State Council Report on the Reflection of China’s Economy in 2013’ to advance the older industries such as the labour-intensive manufacturing industry with high technology and to further develop other industries such as service and culture industries. There was an institutional logic change at the national level from ‘Made in China’, which emphasized China as a world factory, to ‘Created in China’, which highlighted China as a smart manufacturing centre with advanced technology and innovation capacitie (China State Council, Citation2013). Shenzhen, as the window of China’s open door policy and economic development, had been positioned as the focal area for economic reforms.

Under this national level institutional logic shift, the local and regional government authorities in Shenzhen were keen to foster innovation-based technology-intensive industries and other industries such as the culture industry. To this end, the government authorities implemented policies to attract high talent from both domestic and international markets especially by targeting Chinese returnee graduates from overseas higher education institutions. There were considerable competitive incentive policies implemented by Shenzhen municipal government to support overseas talent and Chinese returnee entrepreneurs to start up their businesses in Shenzhen; for instance, free office leasing to start-up firms for a fixed time period, speedy authorization of paperwork for registering a company, and provision of a free consultation and networking service by government agencies (Shenzhen Municipal Government, Citation2019). In light of these local and regional policies, the municipal government officials of Shenzhen and Edinburgh (UK) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in June 2013, which was aimed at providing reciprocal support for incubation spaces in the culture and creative industry in each of the cities (Edinburgh-Shenzhen Creative Exchange, Citation2020).

The aforementioned duties can be interpreted as the championing effort of the broker firm members to reproduce the national and regional institutional logic that was innovation-centred and culture and creative industry-focussed.

Apart from the ESCE project, the broker firm Shenzhen-CreativeCo also championed other major events for Shenzhen municipal government. According to the Shenzhen-CreativeCo Magazine published in 2019, Shenzhen-CreativeCo became one of the exhibition centres for the annual China (Shenzhen) International Cultural Industries Fair and they organized competitions in China and the UK to identify promising SMEs to further develop in Shenzhen.

Diffusing government policies through sensemaking and sensegiving

Diffusing government policies through ‘sensemaking’ and ‘sensegiving’ (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991, 434) means the broker firm members’ action of developing a sense of the government policies by defining a revised conception of the firm identity and activities (sensemaking) in relation to these policies and disseminating the revised firm vision and identity statements to stakeholders (sensegiving). In the case of the broker firm Shenzhen-CreativeCo, the firm members developed a much broader conceptualization of their firm identity and associated cultural industry identity by embedding the national innovation-driven, technology-intensive institutional logic into their personal and company statements:

We have a broader service range. Because of the gene of Shenzhen as a city, we define our service range as culture and technology. In the UK, it is called creative industry. In China, we have a much broader definition of the culture industry. There are 13 industries categorized within cultural industry. It is most often talked about as the intersection between culture industry and another industry. We found out that culture or creative industry does not develop in isolation from other industries. Culture or creative industry often contributes to the advancement of another industry by interacting with that industry. For instance, a company specializing in product manufacturing may need a creative company to develop brand for them like graphic design, product design, etc. More and more products are developed through such diversified cross-industry collaboration. So we did not initiate the intersection of culture and technology but, rather, it is the market trend that drives us to focus on this area. (Project Manager, Shenzhen-CreativeCo)

Shenzhen-CreativeCo, through strategic partnership and investment, centres on the five business areas in culture and tourism, culture and finance, cultural heritage, cultural industrial park, and culture and education. The main business activities include cultural industrial parks, culture and tourism, cultural exhibition centres, creative products, gaming products, collaboration on cultural product design and supply chain, services for start-ups, dissemination of the business model of cultural industrial park management and so forth. (Shenzhen-CreativeCo Magazine published in 2015)

The sensemaking and sensegiving practice of broker firm members contributes to the reproduction of national and regional institutional logic, which builds a solid ground for a broker firm’s active role in facilitating the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs.

Formation processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs

The broker firm can play an active role in nurturing the formation of interfirm collaboration among SMEs by identifying suitable collaborating partners and facilitating SME partners’ identifying complementary goals, seeking consensus on collaboration structure, and agreeing on mutual responsibilities.

Identifying complementary goals

Identifying complementary goals involves the conceptualization of partners’ goal expectations towards collaboration that are often reciprocal rather than in conflict with one another. The identification of complementary goals among interfirm partners takes time and effort from each partner. With the facilitation of the broker firm, SMEs may speed up the partner search and identification of complementary goals with the partner. In the case of SMEs supported by the ESCE project, often, SME members first met with the broker firm members and expressed their goal expectations towards the interfirm collaboration that they wanted to form. In the meantime, these SME members articulated what kind of partner may fit with their goal expectations while meeting with the broker firm members. The broker firm members then actively searched potential partners on behalf of the SMEs through their firm or personal contacts. This process of partner selection and goal identification requires the broker firm members to undertake several iterations of clarification and communication with the SMEs and their potential partners. Such a process of clarification and communication may take longer if the potential collaborating SME members are from different language and cultural backgrounds, as suggested by the following interview comments.

Our main role is to provide matchmaking service; such matching action is critically important. What companies should I bring forward for the matching? Due to the importance of matchmaking, it took us quite a lot of time to do this. There was a successful cultural boutique firm in Edinburgh wishing to find a partner in Shenzhen. Quite a lot of companies wanted to talk to the manager. So I went to each interested company to understand their status and discuss with them. Finally, I filtered all these companies and chose two to three companies which I think appropriate for the Edinburgh company. This has taken quite a lot of workload for me, at least for a week to process all of the information gathered, because many companies do not have enough company information written in English. Also because there are different languages involved in communication between our domestic companies and an overseas company, the communication process takes time. The founder of the Edinburgh company will visit his Hong Kong store in July. We may meet him at that time when he visits Hong Kong to see what his thoughts are at the moment. I think it is important to understand the expectations and pursuits from both sides of the collaboration partners. If you want to help firms achieve mutual benefits out of interfirm collaboration, you must understand what they want to achieve first. We use WeChat and telephone quite a lot to communicate in order to understand what they want to achieve. (Project Manager for ESCE, Shenzhen-CreativeCo)

Before talking to Shenzhen-CreativeCo, it took us quite a while to search for a suitable partner to design our prototype digital air product in Shenzhen. After we explained our criteria to them, they quickly found a good partner in the F518 Park. We have completed our second-generation digital air product design. I’m really pleased with our partner. (CTO, Brit-Digital-Air-Product-Co)

Seeking consensus on collaboration structure

Consensus seeking on collaboration structure means partners’ mutual agreement concerning the structural forms of the interfirm collaboration such as equity joint venture, licencing, supply chain, and strategic partnerships. With the facilitation of the broker firm, SMEs may speed up the consensus-seeking process. In the case of the SMEs supported by the ESCE project, the supply chain collaboration structure was often pursued by partners. The background research work conducted by the broker firm, Shenzhen-CreativeCo, often led to the collaborating SME partners’ accelerated agreement upon the collaboration structure, as explained by the CEO of Brit-China-Fintech-Co:

We signed the contract very quickly with our partner with the great help from the Shenzhen-CreativeCo. We have agreed upon the partnership arrangement with our partner and now we are expanding into other regions of Asia thanks to our partner’s market knowledge.

Agreeing on mutual responsibilities

Based on the collaboration structure, SME partners engage in detailed agreement-building concerning who will be doing what and the quality expectations towards the delivery of such actions. The broker firm can offer advice on the responsibility ranges and quality standards that a collaborating partner may fulfil based on their research work conducted on the collaborating partner. The broker firm’s advice may also help accelerate the responsibility agreement. An operation manager from the China-Digital-Camera-Co commented:

Through the connection of Shenzhen-CreativeCo, we built a partnership agreement with one distributor in the UK and we’ve finalized the contract for our roles and responsibilities.

Development processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs

When the interfirm collaboration among SMEs further develops, the broker firm also champions activities, conferences and events to bring SME partners together to engage in communities of practice. These facilitation activities form grounds for SME partners to build trust incrementally and develop more ambitious goals for their interfirm collaboration.

Engaging in communities of practice

Engaging in communities of practice means that collaborating SME members work as ‘groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis’ (Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder Citation2002, 4). By championing various communities of practice events such as workshops and seminars on particular topics, competition events, overseas education tours, and conference fairs, the broker firm provides an open platform for established and potential SME partners to connect and get to know one another in more depth, as indicated by the following interview comment by the CEO of Brit-China-AI-Robot-Co:

Through the International Cultural Fair Exhibition organized by Shenzhen-CreativeCo, our robotics prototype got increasing attention from our existing partners and potential partners … I have also given a talk at a forum organized by Shenzhen-CreativeCo to share my experience of starting up a company as a Chinese returnee entrepreneur. After that event, I have further developed a partnership with my investor companies.

Building trust incrementally

The collaborative interactions among SMEs foster their mutual trust development over time. Trust is defined as ‘the expectations that partners have about their collaboration and about their partners’ future behaviours in relation to meeting to those expectations’ (Huxham and Vangen Citation2005, 154). The broker firm can facilitate this trust-building process among SME partners by offering peer recommendations on the collaborating partner invoked, which is based on their past interaction with the partner or their understanding of the partner from their professional or social contacts. The CEO of China-Smart-Speaker-Co explained:

When entering an international market, it is good to get recommendations from Shenzhen-CreativeCo about the potential distributors who can be trustworthy partners.

Developing more ambitious goals

With the accumulation of trust, SME partners tend to develop more ambitious goals for their collaboration. By following up the interfirm collaboration progress, the broker firm may provide further support to help collaborating partners achieve more ambitious goals.

Depending on each collaboration case, we may follow up the interfirm collaboration progress. (General Manager, Shenzhen-CreativeCo)

Our second-generation prototype digital air product that we developed with our partner [an industrial design firm based in the F518 Park] is now under production by our collaborating manufacturer thanks to the recommendation of Shenzhen-CreativeCo. (Operation Manager, Brit-Digital-Air-Product-Co)

Collaboration success

The processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs, over time, may lead to collaboration success occurrences in the form of success events, success artefacts and success stories. Success events, artefacts and stories refer to material arrangements (events) and symbolic representations (artefacts and stories) for interfirm collaboration that are widely acclaimed by collaborating partners and associated stakeholders such as central and regional governments and government agencies. These collaboration events, artefacts and stories can be resultant from the broker firm’s facilitation and organization, as suggested by the following interview comment on the success event, artefact and story of the twin-city agreement between Edinburgh and Shenzhen:

As for our national pride, we also want to do such things. For example, the twin cities between Edinburgh and Shenzhen may last in the next 20, 30, or even 40 years. When I get older, I can tell my children that their mum has actively contributed to the formation of such twin-cities. I have a sense of reward from this twin-city arrangement. I think this can be written in our history record and documentaries. I told my colleagues that ‘look, my picture is now included in the history book as a background’. There is a significant meaning in it [twin-city arrangement]. (General Manager, Shenzhen-CreativeCo)

Broker practice: transforming institutional logics

The collaboration success events, artefacts and stories can be disseminated by the community of SMEs, broker firms, governments and government agencies through various communication channels such as radio, television, newspaper, and social media. These interfirm collaboration success occurrences, on the one hand, contribute to the reproduction of the new institutional logics at the national and regional level and, on the other hand, enable the community of SMEs to engage in new meaning-making about the industry level institutional logics, which can arise from the interfirm collaborative practice among SMEs. The broker firm can champion the legitimation of the new meanings for the industry level institutional logics, which contributes to the industry level institutional logics transformation.

Spreading success events, artefacts and stories through various communication channels

The collaboration success events, artefacts and stories from the rhetorical accounts of the collaborating partners and associated stakeholders can be disseminated through diverse communication channels. In the case of the SMEs supported by the ESCE project, the success occurrences concerning the interfirm collaboration among SMEs and the facilitation by the broker firm Shenzhen-CreativeCo were circulated by the central and regional governments’ newspapers and policy documents, the broker firm’s website, magazines and social media channels, and the firm websites of the associated SMEs. The broker firm’s championing role was appraised as the main contributor to the collaboration success occurrences. In the Shenzhen-CreativeCo’s promotion leaflet, one of the interfirm collaborations between the Brit-Digital-Air-Product-Co and their industrial design partner was presented as a successful case study.

After approximately four months [of interfirm collaboration], the prototype of the design came out as satisfying. The cooperation was successful. (Shenzhen-CreativeCo firm promotion leaflet published in 2019)

Until now, there are 16 enterprises settled in both centres [incubators in F518 Park and Edinburgh]. Over the past two years, ESCE has provided services to enterprises in more than 100 cases. (China’s national government newspaper published online in 2017)

Edinburgh has been ranked number one for its FDI strategy in the FDI Intelligence Global Cities of the Future awards 2016/17. This accolade recognises Edinburgh’s collaboration and strategic alliance with Shenzhen as well as the innovative incubator space [led by Shenzhen-CreativeCo] provided for creative and tech investment from Shenzhen at the City of Edinburgh Council’s Creative Exchange incubator hub. (Regional government website of Edinburgh published in 2016)

Legitimating the new meanings for institutional logics emergent from the collaboration success

Through interfirm collaborative practice, the broker firm may champion the legitimation of the new meanings given to the industry level institutional logics by mobilizing other firms in the industry. In the case of Shenzhen-CreativeCo, their facilitation for interfirm collaboration among SMEs has been collectively perceived as an innovation model which can be replicated into other contexts. Moreover, the underlying meanings given to the cultural industry logic, that were mostly culture related, were added with new meanings that centred on ‘culture and technology industry’.

We think Shenzhen-Edinburgh Creative Exchange is an innovation model for interfirm collaboration. … We don’t have concrete business products. We provide services for interfirm collaboration. We constantly adjust ourselves while engaging in interfirm collaboration. For example, before we haven’t thought of engaging in supply chain or industrial design. Then last year we added these two elements into our services and employed one staff to specifically focus on this supply chain area because the client demand is very high. For example, the two company delegates visited us today about the supply chain need. The demand is indeed very high, which is why we formed a new internal project team to handle this. This can be seen as a change in our operation. What we positioned before is different from what we position now in one area. We formed a new department called Smart Shenzhen because we want to serve more companies not only based in Edinburgh. Why it is called Smart because Shenzhen is the largest city for Smart Manufacturing in the Pearl River Delta region. Through Smart Shenzhen, we also want to promote a kind of wisdom embedded in Shenzhen. We are not only doing OEM [original equipment manufacturing] but also we genuinely want to bring the good products and designs of Shenzhen companies into the international markets. Smart Shenzhen can be a service platform for supply chain; it can also be a service platform for our Shenzhen product internationalization. There are quite a number of meanings in this Smart Shenzhen label. (General Manager, Shenzhen-CreativeCo)

Shenzhen-CreativeCo developed a new model on building the value chain for culture and technology industry by becoming an investor for some of the supporting SMEs and facilitating their interfirm collaboration with partners. (Regional government website of Shenzhen published in 2019)

Discussion and implications

This study aims to extend theoretical understanding on interfirm collaboration among SMEs in the light of institutional logics change in an emerging economy context. Particular attention was paid to the formation and development processes of SME interfirm collaboration as well as the interplay between these interfirm collaboration processes and the reproduction/transformation of institutional logics. The research findings highlight the prominent role of government-supported broker firms in fostering the formation and development of SME interfirm collaboration and in reproducing and transforming institutional logics. Based on a qualitative study of the success and failure of policy-implanted interfirm collaboration initiatives, Huggins (Citation2000, 111) concludes that the best SME interfirm collaboration support consists of individual brokers who can ‘mix and overlap the hard business and softer social interests of collaborating participants’. The findings from this study support this view by showing that the brokers can be both individual members and formal organizations such as government-supported incubators located in industrial clusters. Through sensemaking practice (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991), the broker firm members reproduce the institutional logics that are represented by associated government policies through subtly reworking the firm identities and the underpinning routine activities to be in line with the government policies. Through sensegiving practice (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991), the broker firm members disseminate the reworked firm identities and routine activities to related stakeholders such as local government and SMEs. By championing government-sponsored projects and events that promote interfirm collaboration among SMEs, the broker firms gain legitimacy to facilitate and be part of the formation and development of SME collaboration.

As Bliemel et al. (Citation2019, 133) argue, incubators or accelerators can be seen as part of the start-up infrastructure for entrepreneurial clusters by providing ‘tangible and intangible dimensions of start-up infrastructure to form a positively reinforcing cycle of entrepreneurial activities’. This study extends Bliemel et al.’s (Citation2019) view by revealing the broker firm and incubation members’ everyday practices and routines that contribute to the collaborative synergy-building among SMEs in entrepreneurial clusters. In particular, the broker firm members can facilitate partner selection, trust building and internationalization among SME partners. This enhances Smallbone and Welter’s (Citation2012, 100) notion of ‘local agencies’ as part of the enablers for SME cross-border business collaboration and entrepreneurial activities.

Additionally, the research findings suggest that, even though the entrepreneurial cluster is sponsored and/or supported by the government, the government can exercise less intervention to nurture a vibrant cluster by authorizing the broker firm to facilitate SME interfirm collaboration in the cluster. This corroborates with Vernay, D’Ippolito, and Pinkse’s (Citation2018, 916) notion of ‘technology gatekeepers’ who are influential cluster members like the broker firm that receives ‘interpretive flexibility’ to translate government ‘policy initiatives into something meaningful for them’ in the facilitation of entrepreneurial cluster development. In the case of ESCE, the local government in Shenzhen provided financial support to the broker firm and assessed the broker firm’s performance on an annual basis through prescribed key performance indicators with respect to the facilitation of SME interfirm collaboration. However, there was a degree of flexibility given to the broker firm in relation to how such facilitation was conducted for SME partners, which contributed to the creation and development of a ‘vibrant cluster’ (Vernay, D’Ippolito, and Pinkse Citation2018, 901).

Furthermore, the research findings showcase that broker firms are not simply passive recipients of institutional logics, playing an active role in institutional logics transformation. This echoes Kalantaridis and Fletcher’s (Citation2012, 204) view of ‘institutional entrepreneurship’ that refers to organized actors who leverage support and acceptance for new institutional arrangements and plays a key role in catalysing institutional change. In particular, the broker firms enact institutional entrepreneurship by disseminating the success events, artefacts and stories about SME interfirm collaboration and ascribing new meanings and practices for the existing institutional logics. As the research findings suggest, the newly ascribed meanings given for the cultural industry logic, which moved from ‘predominantly culture related’ to ‘the intersection between culture and technology’, reflect what Lounsbury and Crumley (Citation2007, 1005) call ‘collective mobilization’ among broker firms and their collaborating partners.

Theoretical contribution

This paper contributes to the growing body of research regarding a microfoundations lens towards interfirm collaboration among SMEs and institutional logics (Barney and Felin Citation2013; Kalantaridis and Fletcher Citation2012; Liu et al. Citation2017; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Thornton and Ocasio Citation2008) in three ways. First, the research findings provide empirical support for previous interfirm collaboration research that adopted the microfoundations lens by highlighting the role of the broker firm in forming and developing interfirm collaboration (Liu et al. Citation2017; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). Xing, Liu, and Cooper (Citation2018) identify that the regional association of overseas entrepreneurs can offer support to SMEs to help them form interfirm collaboration. The findings from this study illuminate additional sources of support for both the formation and development of interfirm collaboration among SMEs by explicating the roles and practices of the broker firm who often leads incubation centres supported by the national and/or regional government. The broker firm members actively champion government-promoted projects and events and contribute to the diffusion of government policies through sensemaking and sensegiving (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991). Such sensegiving practices of the broker firm members at the individual level can aggregate to the interfirm collaboration at the organizational and industry level. In the case of the broker firm, Shenzhen-CreativeCo, the firm members developed a much broader conceptualization of their firm identity and the associated collective identity of the cultural industry. These firm members also engaged in sensegiving practice to broaden the meanings of the cultural industry by adding innovation and technology into them. Thereby, this research offers empirical insights into the aggregation of individual level factors to the collective level in interfirm collaborations in the context of institutional logics change (Barney and Felin Citation2013; Contractor et al. Citation2019; Kalantaridis and Fletcher Citation2012; Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018; Liu et al. Citation2017; Wry, Lounsbury, and Glynn Citation2011).

Second, this research makes a further contribution to the institutional logics and entrepreneurship literature (Jain and Sharma Citation2013; Kalantaridis and Fletcher Citation2012; Lounsbury and Crumley Citation2007; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Thornton and Ocasio Citation1999, Citation2008) by explicating the key mechanisms employed by broker firms in the reproduction and transformation of institutional logics in an emerging market context. The research findings indicate that, in China, apart from central and regional governments that reproduce and transform institutional logics, the broker firm can play an important role in assisting such institutional logics diffusion and change in the process of facilitating the formation and development of interfirm collaborations. In so doing, these research findings not only provide further empirical support to extant institutional logics literature that address the critical role played by the state in emerging economies (Jain and Sharma Citation2013; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018) but also advance the theorization of institutional logics and entrepreneurship by demonstrating that the broker firm can play an agency role in fostering institutional logics change (Lounsbury and Crumley Citation2007; Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury Citation2012; Thornton and Ocasio Citation2008).

Third, this research casts light on the process approach to interfirm collaborations (Bizzi and Langley Citation2012; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994; Van de Ven Citation1976; Van de Ven and Huber Citation1990; Zhang and Huxham Citation2009, Citation2020) by unfolding the processual dynamics of forming and developing interfirm collaboration among SMEs. With the adoption of qualitative research design, through two rounds of field investigation, this study unfolds the evolvement of interfirm collaborative relationships over time (Bizzi and Langley Citation2012). It thus further illuminates the existing process models of inter-organizational collaborative relationships (Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994) by explicating the routines and practices adopted by the broker firm to facilitate the collaborative relationship formation and development among SMEs.

Policy and managerial implications

This research has several implications for policymakers and SME managers. Governments should recognize the role of private firm actors, such as the broker firm, in the facilitation of diffusing government policies and nurturing economic development. The broker firm can be in the form of an incubator or accelerator located in industrial clusters. Such a broker firm can be established as part of the start-up infrastructure for entrepreneurial clusters to foster a positively reinforcing cycle of entrepreneurial activities (Bliemel et al. Citation2019). Because SMEs are deemed as a major contributor to a nation’s economy, governments may offer more support to the broker firms who can champion government-promoted projects and events, such as industry level expos, conferences, and consultancy on interfirm collaboration, to facilitate the collaboration among SMEs and the diffusion of institutional logics and government policies. When assigning the championing projects and events to broker firms, governments should also consider exercising less intervention to these broker firms in their facilitation of SME interfirm collaboration. This can contribute to the sustainable growth of SME interfirm collaboration (Huggins Citation2000; Vernay, D’Ippolito, and Pinkse Citation2018).

Past studies have revealed that attracting talented overseas returnees can be a critical and unique component of the overall economic growth strategies in China (Wang and Liu Citation2016; Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018). Building on this view, this research suggests that emerging economies may develop policy initiatives to establish a supporting external environment such as industrial clusters and incubation centres, which can be championed by key broker firms, for SMEs owned by overseas returnees to boost economic development. As for SME managers, the professional advice and support offered by broker firms can help accelerate the development and internationalization of SMEs. The SME managers may consider fostering links and collaborative relationships with broker firms to acquire their needed resources and attain value creation.

Future research directions

This study offers several fruitful directions for future research on interfirm collaboration among SMEs in emerging economies. First, future research can examine the processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs from different theoretical perspectives such as resource-based theory (Crick, Crick, and Chaudhry Citation2021; Huggins and Johnston Citation2010; Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021), network theory (Huggins Citation2000; Lechner and Dowling Citation2003; Leppäaho and Pajunen Citation2018; Scott, Hughes, and Kraus Citation2019), and knowledge-based view (Lyu et al. Citation2020). For instance, Lechner and Dowling (Citation2003) draw upon network theory (Granovetter Citation1973) to examine the growth process of entrepreneurial firms through interfirm networks. Their research findings suggest that the transformation of weak into strong ties for value exploitation is crucial. Future research can investigate the role of broker firms in the transformation of weak to strong ties in SME interfirm networks.

Second, future research can conduct comparative studies either on the different sizes and/or relationship types of the firms as the research subjects or on the emerging economies at divergent developmental stages as the research contexts. For example, comparing the interfirm collaborative relationship patterns between SMEs and multinational corporations can unfold how the size of a firm matters in the formation and development of interfirm collaborations (Lahiri, Kundu, and Munjal Citation2021). The role of collaborative goal-setting and attainment can also be further examined in future studies that compare the interfirm collaborative relationship of SMEs having complementary goals with those collaborative relationships that involve competing goals (Crick Citation2020; Crick and Crick Citation2021a, Citation2021b; Lechner and Dowling Citation2003). Alternatively, comparing the interfirm collaborative relationships among SMEs across different emerging economy contexts such as China and Vietnam may entail the distinctive institutional logics invoked in emerging economies (Xing, Liu, and Cooper Citation2018).

Third, future research can be conducted longitudinally in a more than one-year time span to capture the formation, development or perhaps termination of interfirm collaborations as more collaborative relationship patterning may emerge over a longer time period. Fourth, future research could examine the collaborative relationships between SMEs and other agents and/or social actors (de Bruin, Shaw, and Lewis Citation2017), such as government agencies, non-governmental organizations, universities and so forth, to illuminate the developmental processes of inter-organizational collaborative relationships (Liu et al. Citation2017; Ring and Van de Ven Citation1994; Van de Ven and Huber Citation1990).

Conclusion

This research unfolds the formation and development processes of interfirm collaboration among SMEs in the context of institutional logics change in an emerging economy. In particular, it reveals the everyday collaborative practices and routines adopted by broker firm members to nurture SME interfirm collaboration and to reproduce and transform institutional logics. The research findings suggest that understanding the role of the external and internal actors, such as governments and broker firms, is important for advancing studies on interfirm collaboration. Therefore, this research can serve as a departure point for further theorization of interfirm collaborations among SMEs.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Jörg Sydow for his valuable feedback on the earlier drafts of this article. A special thanks to the editor Miruna Radu-Lefebvre and the reviewers for their constructive feedback and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Another similar concept to interfirm collaboration is coopetition that refers to the interplay between cooperation and competition among rival firm members who engage in collaborative activities such as knowledge and experience sharing (Bengtsson and Kock Citation2014; Crick Citation2020; Crick and Crick Citation2021a, Citation2021b). However, there is still a subtle difference between these two concepts. Interfirm collaboration is more all-embracing, potentially involving multiple organizational stakeholders who may not necessarily be competitors, whereas, coopetition refers to organizations cooperating with their competitors. The notion of interfirm collaboration is adopted in this research to cover the wide relationship types among organizational stakeholders.

References

- Ahmadsimab, A., and I. Chowdhury. 2021. “Managing Tensions and Divergent Institutional Logics in Firm–NPO Partnerships.” Journal of Business Ethics 168 (3): 651–670. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04265-x.

- Barney, J., and T. Felin. 2013. “What are Microfoundations?” Academy of Management Perspectives 27 (2): 138–155. doi:10.5465/amp.2012.0107.

- Bengtsson, M., and S. Kock. 2014. “Coopetition—Quo Vadis? Past Accomplishments and Future Challenges.” Industrial Marketing Management 43 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2014.02.015.

- Bianchi, P. 1993. “The Promotion of Small Firm Clusters and Industrial Districts: European Policy Perspectives.” Journal of Industry Studies 1 (1): 6–29.

- Bizzi, L., and A. Langley. 2012. “Studying Processes in and around Networks.” Industrial Marketing Management 41 (2): 224–234. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.01.007.

- Bliemel, M., R. Flores, S. De Klerk, and M. P. Miles. 2019. “Accelerators as start-up Infrastructure for Entrepreneurial Clusters.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 31 (1–2): 133–149. doi:10.1080/08985626.2018.1537152.

- Casson, M., and M. D. Giusta. 2007. “Entrepreneurship and Social Capital: Analysing the Impact of Social Networks on Entrepreneurial Activity from a Rational Action Perspective.” International Small Business Journal 25 (3): 220–244. doi:10.1177/0266242607076524.

- China State Council. 2013. “China State Council Gazette.” Accessed 10 February 2022. https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/state_council_gazette/2015/06/08/content_281475123302284.htm.

- Contractor, F., N. J. Foss, S. Kundu, and S. Lahiri. 2019. “Viewing Global Strategy through a Microfoundations Lens.” Global Strategy Journal 9 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1002/gsj.1329.

- Corley, K. G., and D. A. Gioia. 2004. “Identity Ambiguity and Change in the Wake of a Corporate spin-off.” Administrative Science Quarterly 49 (2): 173–208. doi:10.2307/4131471.

- Crick, J. M. 2020. “The Dark Side of Coopetition: When Collaborating with Competitors Is Harmful for Company Performance.” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 35 (2): 318–337. doi:10.1108/JBIM-01-2019-0057.

- Crick, J. M., D. Crick, and S. Chaudhry. 2021. “Interfirm Collaboration as a performance-enhancing Survival Strategy within the Business Models of Ethnic minority-owned Urban Restaurants Affected by COVID-19.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research ahead-of-print (ahead-of-print). doi:10.1108/IJEBR-04-2021-0279.

- Crick, J. M. 2021. “Qualitative Research in Marketing: What Can Academics Do Better?” Journal of Strategic Marketing 29 (5): 390–429. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2020.1743738.

- Crick, J. M., and D. Crick. 2021a. “The dark-side of Coopetition: Influences on the Paradoxical Forces of Cooperativeness and Competitiveness across product-market Strategies.” Journal of Business Research 122: 226–240. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.08.065.

- Crick, J. M., and D. Crick. 2021b. “Rising up to the Challenge of Our Rivals: Unpacking the Drivers and Outcomes of Coopetition Activities.” Industrial Marketing Management 96: 71–85. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.04.011.

- de Bruin, A., E. Shaw, and K. V. Lewis. 2017. “The Collaborative Dynamic in Social Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29 (7–8): 575–585. doi:10.1080/08985626.2017.1328902.

- Edinburgh-Shenzhen Creative Exchange. 2020. “Edinburgh-Shenzhen Creative Exchange (ESCE).” Accessed 10 February 2022. http://www.edinburghshenzhen.com/View/Aboutus.aspx.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., M. E. Graebner, and S. Sonenshein. 2016. “Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis.” Academy of Management Journal 59 (4): 1113–1123. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.4004.

- Felin, T., N. J. Foss, K. H. Heimeriks, and T. L. Madsen. 2012. “Microfoundations of Routines and Capabilities: Individuals, Processes, and Structure.” Journal of Management Studies 49 (8): 1351–1374. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01052.x.

- Festing, M., L. Schäfer, and H. Scullion. 2013. “Talent Management in medium-sized German Companies: An Explorative Study and Agenda for Future Research.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24 (9): 1872–1893. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.777538.

- Fisher, G., and H. Aguinis. 2017. “Using Theory Elaboration to Make Theoretical Advancements.” Organizational Research Methods 20 (3): 438–464. doi:10.1177/1094428116689707.

- Foss, N. J. 2011. “Invited Editorial: Why micro-foundations for resource-based Theory are Needed and What They May Look like.” Journal of Management 37 (5): 1413–1428. doi:10.1177/0149206310390218.

- Friedland, R., and R. R. Alford. 1991. “Bringing Society Back.” In The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis: Symbols, Practices, and Institutional Contradictions, edited by W. W. Powell and P. DiMaggio, 232–263. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Gioia, D. A., and K. Chittipeddi. 1991. “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation.” Strategic Management Journal 12 (6): 433–448.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research:Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Granovetter, M. S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. doi:10.1086/225469.

- Greenman, A. 2013. “Everyday Entrepreneurial Action and Cultural Embeddedness: An Institutional Logics Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (7–8): 631–653. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.829873.

- Hemmert, M. 2019. “The Relevance of inter-personal Ties and inter-organizational Tie Strength for Outcomes of Research Collaborations in South Korea.” Asia Pacific Journal of Management 36 (2): 373–393. doi:10.1007/s10490-017-9556-6.

- Hoskisson, R., L. Eden, C. Lau, and M. Wright. 2000. “Strategy in Emerging Economies.” Academy of Management Journal 43: 249–267.

- Huggins, R. 2000. “The Success and Failure of policy-implanted inter-firm Network Initiatives: Motivations, Processes and Structure.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 12 (2): 111–135. doi:10.1080/089856200283036.

- Huggins, R., and A. Johnston. 2010. “Knowledge Flow and inter-firm Networks: The Influence of Network Resources, Spatial Proximity and Firm Size.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22 (5): 457–484. doi:10.1080/08985620903171350.

- Huxham, C., and S. Vangen. 2005. Managing to collaborate:The Theory and Practice of Collaborative Advantage. London: Routledge.

- Jain, S., and D. Sharma. 2013. “Institutional Logic Migration and Industry Evolution in Emerging Economies: The Case of Telephony in India.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 7 (3): 252–271. doi:10.1002/sej.1160.

- Junker, B. H. 2004. “The Field Work Situation: Social Roles for Observation.” In Social Research Methods: A Reader, edited by C. Seale, 221–225. London: Routledge.

- Kalantaridis, C., and D. Fletcher. 2012. “Entrepreneurship and Institutional Change: A Research Agenda.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 24 (3–4): 199–214. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.670913.

- Lahiri, S., S. Kundu, and S. Munjal. 2021. “Processes Underlying Interfirm Cooperation.” British Journal of Management 32 (1): 7–19. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12476.

- Langley, A. 2009. “Studying Processes in and around Organizations.” In Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods, edited by D. Buchanan and A. Bryman, 409–429. London, UK: Sage Publications.