?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This research uses hierarchical linear modelling to test the KSTE in a developing-country context. By trying this theory on a different setting as is usually studied, we attempt to identify boundary conditions, expanding this theory’s understanding. Results show the low effectiveness of this theory in a developing economy, suggesting that additional dimensions are needed to understand it completely. In reviewing the high-tech sector (the only sector in which we found evidence that the KSTE mechanisms apply), our data shows the importance of diversity for technological innovation and thus for firms born out of spillovers. Finally, we find that easiness to start a business interacts with human capital into forming high-tech new firms. Under a more bureaucratic system, high-knowledge human capital will have fewer incentives to switch from employment to self-employment and start a venture. By dealing with the specificities of developing economies when dealing with the KSTE, policymakers can avoid applying police recipes coming from findings related only to developed economies that cannot fit with the characteristics of these countries. In this context, this phenomenon is not particularly relevant for fostering new ventures, joining on the call of avoiding standardized strategies to build efficient entrepreneurial ecosystems.

1. Introduction

Most western economies use entrepreneurship as a public policy tool for fostering economic growth (OECD Citation2019). As such, in their anxiousness to catch up quickly with advanced nations, developing economies tend to replicate successful public policies from developed countries’ (Wasdani and Manimala Citation2015). However, empirical evidence has shown that when policies are not correctly internalized and adequately adapted to local conditions, their implementation turns difficult, and more importantly, the subsequent impact on the economy is not necessarily the expected one (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021; Eesley et al. Citation2018; Simón-Moya, Revuelto-taboada, and Guerrero Citation2014). Further, it has been suggested that high-growth start-ups enhance knowledge spillovers (Cerver-Romero, Ferreira, and Fernandes Citation2020) such that some firms, unable to exploit their research, leave this new knowledge for others to develop into new ventures. Based on this, policymakers have developed several initiatives around spillovers under the axiom that investment in knowledge is a key driver of regional and macroeconomic growth (Romer Citation1990; Saxenian Citation1994). The stream’s core argument is that external benefits from the creation of knowledge accrue for third parties differently than for the knowledge creators (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2010).

The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship (KSTE), where ‘entrepreneurial activity is a conduit via which knowledge spillovers contribute to innovation and economic development’ (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008), has been empirically tested and supported mainly in developed economies, such as European countries (Acs et al. Citation2009; Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2007), the United States (Tsvetkova, Thill, and Strumsky Citation2015; Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019), and other OECD countries (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009), but also for regions and industries (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005). In essence, this theory posits that entrepreneurial opportunities are systematically created by investments in knowledge by incumbent organizations (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2007). This knowledge created endogenously results in knowledge spillovers, enabling entrepreneurs to identify and use the best ideas for business opportunities (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009). Hence, a context with more available knowledge will generate more entrepreneurial opportunities, positively impacting economic growth. However, the KSTE has several underlying implicit assumptions based on its having been theorized in a developed context, such as: a flow of knowledge that neatly can be transformed into commercialized products and services, availability of local resources (human capital, financial inputs, and legal services); an appropriate market incentive mechanism that facilitates the transition from worker to entrepreneur; and effective support given by key institutions to entrepreneurial activity (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015). As such, the theory may operate differently when these implicit assumptions are challenged. This feature is theoretically interesting and practically relevant for countries designing such policies. What are the boundary conditions of the KSTE when testing it in a developing country? By identifying how this theory works in less than ideal settings, we can expand upon the assumptions in which it stands, and further increases its understanding. To explore these issues, we use the case study of Chile as a relevant empirical context to study the impact of challenging these implicit assumptions.

Considering emerging markets operate differently than advanced economies (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2006; Bradley and Klein Citation2016; Foo et al. Citation2020; Grilli, Mrkajic, and Latifi Citation2018; Mingo Citation2013; Zacharakis, McMullen, and Shepherd Citation2007) and similar regulations can generate different results depending on national context (Bustamante Citation2019; Eesley et al. Citation2018; Simón-Moya, Revuelto-taboada, and Guerrero Citation2014), Chile is a particularly interesting case to analyse the effectiveness of this theory for several reasons. First, Chile’s open economy, well-developed institutions, and strong rule of law make it an attractive investment destination (US Congressional Research Service Citation2021). Indeed, it represents one of the most competitive economies in the region with the highest development level (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013), and entrepreneurship has been an essential part of the national growth and development strategy since 2005 (Oyarzo et al. Citation2020). In this sense, the Chilean case enables research on changes in the type of entrepreneurial activity in a context where the institutional framework has remained generally strong and stable during the last few decades (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021). Further, the Chilean economy represents one of the world’s most productive entrepreneurship ecosystems (Espinoza et al. Citation2019), with every region having distinctive entrepreneurial (Muñoz et al. Citation2020a) and innovation (Gatica-Neira Citation2019) ecosystem characteristics. However, the typical expectation that a developed economy should emerge progressively with the appropriate enactment of a system of rules and regulations has not been observed. Thus, Chile provides an intriguing case to examine questions about the role of knowledge spillovers in creating and developing entrepreneurial activity. This unique feature of the study, in addition to the intriguing analysis of the Chilean case, offers a new perspective to understand the mechanisms involved in the emergence of knowledge spillovers. Even though most programmes oriented towards promoting entrepreneurship have a national scope, we presume that the significant differences in the quantity and quality of entrepreneurial activity between regions (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013; Atienza, Lufín, and Romaní Citation2016; Modrego et al. Citation2014, Citation2015) may be conditioned by the reach of knowledge spillovers. This is because a region with more knowledge spillovers would imply more opportunities left for entrepreneurs to discover and thus develop into the market in new ventures.

In this research, we use an hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) approach to perform a systematic test of the KSTE in a developing-country context while studying different economic sectors based on the grade of knowledge needed. Our main empirical results can be summarized as follows: First, the effects of the KSTE are only applicable in quite specific industries of high-knowledge use, so a generalization over our results may suggest that the theory’s predictive power is less effective in developing economies. This, in turn, suggests that additional dimensions are needed to completely understand this theory. Second, in reviewing the knowledge-intensive industry sector, the regional grade of industry diversity has an enhancing effect on the development of high-tech entrepreneurial activity. This supports previous evidence on the importance of having diverse industries for technological innovation (Rosenzweig Citation2017) and thus for firms born out of spillovers (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2017). Third, we find an interaction effect between the influence of human capital on high-tech firm creation and the lowering of bureaucratic barriers to starting a business. This shows the importance of institutional factors in fostering the crossover into entrepreneurship, as under a more bureaucratic system, the high-knowledge human capital will have fewer incentives to switch to self-employment by starting a business.

This research contributes to the entrepreneurship literature in three ways. First, while in developed regions, the KSTE holds in markets with a high dependency on knowledge and in some cases fails in general or low-technology sectors, in our developing-economy setting, we only find validation for the KSTE in the high-tech sector. This finding may suggest that more dimensions of this theory are not yet considered in the literature. Thus, we present some complementary ideas to expand the framework. Second, while Chile has a similar entrepreneurial ecosystem and innovation rates as developed countries, the transfer of knowledge from incumbent firms into new entrepreneurship has not occurred as expected. This paper presents some possible explanations for this. Third, this paper also provides lessons for other developing economies that want to foster growth through the KSTE. In this context, this phenomenon is not particularly relevant for fostering the creation of new ventures. This does not mean that we recommend encouraging less knowledge creation, as it is still a relevant engine for complexifying the economic matrix, increasing value-added, boosting exporting, etc., but we argue that it will produce fewer or no KSTE-born companies. Policymakers who want to promote growth by investing in research and development will have to consider the framework via which knowledge is produced before blindly investing in projects, like technology parks or innovation programmes, following recipes made in the developed world. In this way, we join the literature’s growing criticisms that discredit the overreliance on standardized strategies to build efficient entrepreneurial ecosystems (Brown and Mason Citation2017; Muñoz et al. Citation2020a; Spigel Citation2017).

2. Theoretical framework

According to the KSTE, entrepreneurial ventures are among the conduits through which knowledge produces economic growth (Z. Acs and Armington Citation2006; Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009; Z. Acs and Plummer Citation2005; Audretsch Citation1995; Audretsch, Keilbach, and Lehmann Citation2006; Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008; Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005; Qian, Acs, and Stough Citation2013). Most of the research within this framework has centred on new knowledge as one of the major sources of entrepreneurial opportunities, as start-ups are seen as the main mechanism that permeates the so-called knowledge filter (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009; Cerver-Romero, Ferreira, and Fernandes Citation2020). This notion of knowledge filter points to the obstacles, like organizational or institutional barriers, that hinders the realization of the market value of new knowledge being commercialized (Carlsson et al. Citation2009; Qian Citation2018; Qian and Yao Citation2017). By enabling knowledge spillovers, entrepreneurs introduce new products or services into the market based on that tacit knowledge that would otherwise be left uncommercialized (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009). Consequently, entrepreneurship is considered the ‘missing link’ between investments in new knowledge and economic growth by serving as a channel for knowledge spillovers (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008; Braunerhjelm et al. Citation2010).

The underlying argument about why entrepreneurship contributes to innovation and, ultimately, territorial revitalization and local prosperity relies on the idea that knowledge spills over between economic agents. The recipients are the ones who better recognize its market value and act faster to commercialize it. However, prior studies have noted that this mechanism’s magnitude depends on various factors in the regional entrepreneurial ecosystem, including knowledge bases, absorptive capacity, competition, networks, diversity, and culture (Qian Citation2018). As the knowledge-spillover process is far from automatic (Liu et al. Citation2010), more evidence is needed to understand it when these general assumptions of the KSTE are relaxed, and new constraints reflecting the context of developing countries are introduced (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015; Iftikhar, Ahmad, and Audretsch Citation2020). In particular, González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2015) state that certain assumptions of the KSTE may not hold in less developed countries compared to developed economies, reducing the theory’s effectiveness. First, the flow of knowledge between local markets and institutional agents and its transformation into products and services is a process that does not seem to evolve as successful in developing countries as in developed countries (Armington and Acs Citation2002). Second, developing countries lack available human capital, financial inputs, legal services, and other advantages present in developed countries (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2007; Qian and Acs Citation2013). Third, market incentive mechanisms vary between countries (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2010). And fourth, key support provided by institutions, including universities, national innovation systems, and industry clusters, to stimulate (innovation-driven) entrepreneurship operates differently in developing and developed contexts (Qian and Yao Citation2017).

In sum, we argue that the core arguments of the KSTE – (1) growth and knowledge are endogenous, as new firms are born from knowledge and create knowledge themselves (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009), (2) knowledge must accumulate in a region (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005), and (3) entrepreneurs act as knowledge filters by selecting and pursuing the best ideas (Braunerhjelm et al. Citation2010) – may not appropriately activate economic development on the emerging economies. This is regardless of when apparent macro-level requirements – a strong and stable economy with intensive support to entrepreneurship – are fulfilled.

2.1 Hypotheses development

For our hypotheses development, we expand on the previously stated four assumptions by González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2015) that could fail when changing from a developed country to a developing country setting, thus reducing the effect of the KSTE mechanism. resumes the KSTE mechanism and our hypotheses.

Figure 1. KSTE theoretical model with boundary conditions. Based on Qian (Citation2018). Each boundary condition contains one specific hypothesis, affecting a different part of the KSTE model. Market incentives mechanisms affect how firms produce knowledge (H3), its usefulness on how it can flow into new ventures (H1), selected by the human capital in place, which in turn act as a filter (H2), and thanks to the key support by institutions, can transition into entrepreneurship to exploit these ideas (H4) .

2.1.1 Flow of knowledge into firms

The occurrence of the KSTE has two major implications for regional economic development. First, ceteris paribus, a higher level of local knowledge creation leads to a higher level of start-up activity, as the former gives entrepreneurs more opportunities to discover and exploit. Therefore, investing in R&D or knowledge creation may contribute to a more entrepreneurial regional economy. Many empirical studies have provided evidence of this positive relationship in regional economies (Audretsch, Bönte, and Keilbach Citation2008; Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005; Plummer and Acs Citation2014; Qian, Acs, and Stough Citation2013; Tsvetkova Citation2015). However, as developing countries tend to have less knowledge-intensive industries, this flow of new inventions based on knowledge spillovers could find less usefulness and thus not find market opportunities so easily. For example, the agriculture industry sector, usually not highly knowledge dependent, could benefit from knowledge spillovers from the automatization industry, but only in economies that already use machines for extraction and are not made entirely by labour-intensive processes as low-income countries usually do. Another issue in developed countries is the grade of innovation that comes from them, as agents are more prone to imitative innovation than real ones (Koellinger Citation2008; Minniti and Lévesque Citation2010). This means that their products are only locally innovative, having to compete in the local market with the alternative of imported foreign technology (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015), adding risk to the process of commercializing their innovation and thus hindering the KSTE.

In sum, if the KSTE theory holds in a less developed country, we should expect that more available knowledge in a region would turn into new ventures, but only in sectors of the economy more knowledge-dependent for innovation. Therefore, we can state our first hypothesis.

H1: Created and available knowledge in a region will be positively associated with entrepreneurial activity in highly knowledge-dependent sectors.

2.1.2 Effect of human capital

The second implication of the KSTE for regional economic development is that for the entrepreneur to act as a knowledge filter and select the best available knowledge, their ability to do so depends on their own intrinsic capabilities. By introducing the entrepreneurial ‘absorptive capacity’ (i.e. the ability to understand new experiences, recognize these experiences’ value, and commercialize them by creating a firm), Qian and Acs (Citation2013) also extend the application of the KSTE to non-inventor entrepreneurs’ behaviour. For example, an entrepreneur not affiliated with a specific university may exploit the market value of a new idea that originates from the university. In this case, the entrepreneur is not the inventor himself but has sufficient technical background to understand the new idea and discover its potential market value when communicating with the university research staff.

The other role of the human capital in a region is in the knowledge generation process, as incumbent firms depend on them for R&D activities. Empirically, Qian (Citation2017b) has shown the direct and moderating effects of various labour-market skills (human capital measures) on knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship in US cities. In particular, these skills, including cognitive, social, technological, problem-solving, systems, and resource-management skills, moderate the entrepreneurial process of commercializing knowledge. Thus, the higher the absorptive capability of potential entrepreneurs in a region, they will have superior abilities to detect and discover the best ideas to commercialize, thus creating more new business in the region. On the other side, a region without absorptive capability, even with productive knowledge centres, would imply that its knowledge would end up being unused and spoilt.

H2: The level of Human capital, representing the absorptive capacity of a region, will be positively associated with entrepreneurial activity.

2.1.3 Market incentive mechanisms

Market incentive mechanisms vary between countries, as the contextual conditions (i.e. markets and institutions) in developing countries to launch innovative start-ups are less creative and supportive than those in advanced economies (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2010). Therefore, the availability of entrepreneurial opportunities arising from knowledge spillovers in developing economies is expected to be low and not uniform among the poorest countries (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015). This in turn leads to a lower expected return on entrepreneurship and weaker incentives to form innovation-driven start-up firms.

While a context with more knowledge infrastructure will generate more entrepreneurial opportunities, in contrast, one with less (value-yielding) knowledge will generate fewer entrepreneurial opportunities (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2007). Under this setting, recent literature has stated the importance of agglomeration dynamics to enhance regional capabilities to innovate. However, the literature is still inconclusive if Marshallian specialization or Jacobian diversification externalities will favour overall regional innovativeness better (Van Der Panne Citation2004). On the one hand, the specialization thesis asserts that regions with production structures towards a particular industry tend to be more innovative in that specific industry, allowing for knowledge to spill over to similar firms (Cavallo et al. Citation2020). The current discourse on specialization is on the so-called smart specialization, where regions specialize in one particular industry sector according to hidden opportunities (Balland et al. Citation2019) or specific regional capabilities (Szerb et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, the diversification thesis argues that knowledge spills over between different (but related) industries, causing diversified production structures to be more innovative (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2017; Bishop Citation2012; Colombelli, Orsatti, and Quatraro Citation2021; Rosenzweig Citation2017).

Because there is still no consensus in the literature on which is more important, it has been suggested that it depends on context, for example, on the industry’s lifecycle (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009) or an industry’s source, nature, and direction of innovations (Colombelli, Orsatti, and Quatraro Citation2021). In particular, Rosenzweig (Citation2017) and later supported by Audretsch and Lehmann (Citation2017) favour that a country enhanced economic performance can be attributable to technological context, i.e. ‘technology taken out of its original context and adapted to an entirely different technological context’. This suggests that a country’s firm capability to commercialize knowledge intended for a very different technological context bestows competitive advantage.

While in previous KSTE studies, there is some consensus on the overall importance of Jacobian spillovers (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2007; Capone, Lazzeretti, and Innocenti Citation2019; Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019), we did not find previous evidence for this theory in low-knowledge countries. Nonetheless, given that for the specialization agglomeration to be a successful enhancement for innovative new ventures depends on the grade of knowledge complexity, we should not expect this kind of spillovers to be relevant.

H3: The level of industry diversification, representing the variety of activities in a region’s economic sector, will be positively associated with entrepreneurial activity.

2.1.4 Key support by institutions

Finally, the process by which employees of an existing firm leave their employment to initiate a new business venture, known as entrepreneurial spawning (Garrett et al. Citation2017), differs in high – or low-barrier industry groups. When entry into low-barrier lines of business requires only modest amounts of financial capital and little education levels, in high-barrier markets, it is the opposite (Lofstrom, Bates, and Parker Citation2014). Besides market conditions, other relevant factors for this are risk aversion, legal restrictions, bureaucratic constraints, labour market rigidities, taxes, or lack of social acceptance (Parker Citation2018). However, for developing countries, the most relevant are financial, skill relationships, and market and institutional barriers (Torres de Oliveira, Gentile-Lüdecke, and Figueira Citation2021). A lack of these factors in a given country could explain why economic agents might decide against starting a new venture, even when possessing knowledge that promises potential profit opportunities (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009). In particular, the degree of the bureaucracy process to start a business can contain most of them, as it increases costs, time, legal issues, and ultimately uncertainty to an employee’s transition to entrepreneurship. A higher barrier to formalization in low-tech firms can lead to informality, a common feature of most developing economies. Two important concerns arise from this. First, informal firms tend to be less productive than formal firms. Second, the competition from informal firms can weigh on firms’ productivity in the formal sector (Amin and Okou Citation2020). Reducing such barriers can have the following effects: (1) As it is easier for informal businesses to incorporate into a firm, there should be a large sample of existing firms that now should be doing it for its enhancement effects. (2) An easier process will leave more available resources (human, financial) for this critical stage for survivability. These positive effects are compensated with the negative effect of increment of competition, thus reducing the survivability of inefficient firms. As there is plenty of evidence that lower entry barriers into a market increase entrepreneurship overall (Klapper, Laeven, and Rajan Citation2006), we expect the same effect, ceteris paribus, in our case.

H4: A lower barrier to entrepreneurship, represented by the amount of paperwork, costs, and time for legally establishing a new venture, will be positively associated with overall entrepreneurial activity.

3. Data, variable definitions, and methodology

3.1 Research setting

As Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007) argue, unusual or extreme cases are instances of theoretical sampling that may be very useful for building theory, helping to reveal different aspects of the phenomenon at hand and generate new theoretical insights (Siggelkow Citation2007). The data we use to test our hypothesis are economic data from the country of Chile, a Latin American country in a transition stage from developing to developed status. Regarding the choice of the country, we believe that this transition stage is what gives this country its special status and appropriate characteristics for the testing of the KSTE theory. As ‘developed’ is a loosely defined term, some authors have stated that Chile has already left the development group but is not quite actually developed. For example, the OECD graduated Chile from its Development Assistance Committee list in 2018 after defining it as a new ‘high-income country’.Footnote1 Also, the World Bank classifies Chile as a ‘high-income country’ with a human development index of ‘very high’.Footnote2 However, at the same time, the country still lacks an innovative-driven economy,Footnote3 a characteristic usually related to developed countries and suffers a high economic (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013; Espinoza et al. Citation2019).and human capital (Aroca and Eberhard Citation2015) disparity,amount its populationFootnote4 and regions

We consider at least three main arguments to justify the appropriateness of studying this country regarding the KSTE. First, following the emergence of a more entrepreneurial capitalist class in the 1980s (Schurman Citation1996), Chile has made tremendous progress towards greater economic prosperity, more than doubling its per capita income while lifting many Chileans out of poverty (OECD Citation2021). Although the main institutional approach still supports big corporations and concentration of power, the last 20 years have seen some considerable effort to shift this trend into a more entrepreneurship-led economy (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021; Feige and Feige Citation2014; Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee Citation2018). Thanks to its stable macroeconomic context, strong open market, and well-developed institutions, the country is the most competitive economy with the highest development levels in Latin America and the Caribbean (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013). Also, it stands out among transitioning and developing economies with an unusually high growth-oriented entrepreneurship rate (Stam, Citation2013) and innovative high rates among nascent entrepreneurs (Koellinger Citation2008). As such, it is considered one of the world’s best entrepreneurial ecosystems (Z. Acs et al. Citation2019). However, this contradicts with a severe lack of innovation outcomes, as it has among OECD countries the lowest R&D spending, patenting activity, and economic complexityFootnote5 (World Economic Forum Citation2019). In fact, for Koellinger (Citation2008), the main issue is not a lack of innovative entrepreneurs, but the type of innovation that comes out of them, characterizing it as only innovations at a local level and not necessarily novel for the global market. This paradoxical state allows us to discard any bias due to economic or institutional effects that would arise with another developing country when comparing our results with a developed country, thereby enabling us to focus on our model variables.

Second, while being a small country with only 19 million inhabitants, Chile’s particular longitudinal form gives culturally and economically heterogeneous regions with a unique geographic and climate diversity. This creates regional gaps of significant development differences (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013; Espinoza et al. Citation2019) and distinctive entrepreneurial (Muñoz et al. Citation2020a) and innovation (Gatica-Neira Citation2019) ecosystem characteristics, with different levels of success and configurations. For example, while the northern mining regions receive robust private funding, in the more impoverished southern regions like Araucanía (with a high percentage of rural indigenous inhabitants) or Aysén (sparsely populated with rich European and Argentinian Gaucho influences), support mainly comes from public funds. This allowed us to obtain high variability in our sample in a relatively small country (Muñoz et al. Citation2020a). Although working on a more fine detailed level of analysis should deliver more robustness to our results, Given the non-existence of data, we can only deliver some reasons why this should not be an issue. The main reason is that, for each region, the knowledge production is mainly concentrated in its capital, with low activity outside of it (Modrego et al. Citation2015). One notable characteristic of the country, similar to other Latin American countries, is the high rurality characteristics outside of its regional capitals. As rural communes are less innovative than urban (Modrego and Foster, Citation2021), and their entrepreneurs tend to have fewer growth expectations (Mahn et al., Citation2022), this limits their potential for knowledge production. Combined with the fact that Innovation policies tend to be regional-based (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013), we can consider each region as an independent EE – as also (Villegas Mateos and Amorós., Citation2019), suggests.

Third, in general, there is evidence that Chilean firms’ productivity is not affected by innovative results nor research expenditures in the short-run (Benavente Citation2006). Adding to the lack of a robust venture-capital market (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021) and the concentration of resources in the core regions of the country (Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon Citation2013), it has led to highly heterogeneous regional innovative capabilities (Gatica-Neira Citation2019; Modrego et al. Citation2015). This intensifies the disparities in the regions’ economic development levels. Given the regions’ path-dependent characteristics (Espinoza et al. Citation2019; Oyarzo et al. Citation2020), this state has continued over time. To improve the shortcomings of the ecosystem, the Chilean Economic Development Agency (CORFO) came in to fill the gap, delivering seed money, mentoring systems, and R&D funding, with mixed results (Crespi et al. Citation2020; Gonzalez-Uribe and Leatherbee Citation2018; Navarro Citation2018; Romaní, Atienza, and Amorós Citation2013). With all this expending effort, policymakers expected that all the generated knowledge would transition into new ventures, generating KSTE-related endogenous growth, and thus push the economy forward into a developed, innovation-driven economy – but it has not. In fact, GDP per capita growth has been falling since its higher value in 1992 (World Bank Citation2021), and The World Economic Forum (Citation2019) ranked Chile five places below where it was a decade ago, still being categorized as an economy in transition into the Innovation-driven Stage. So, after two decades of investments into knowledge production, not only has the country not advanced into the innovative stage, but also slowed down against their competitors.

Concerning the study’s timeframe, we focused on the years 2010 to 2019, a period of particular economic and financial stability for the country, reducing external shocks that could have affected our analysis. In February 2010, the 8.8 magnitude Maule earthquake caused severe damage to the central part of the country’s infrastructure, requiring heavy public investment in reconstruction. As 2009 marked the year in which informal institutions started to legitimize entrepreneurship as a real alternative to employment (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021), this event reinforced the positive attitude towards entrepreneurship even more (Bustamante, Poblete, and Amorós Citation2020; Mandakovic, Cohen, and Amorós Citation2015), which followed a decade of economic and social stability. Subsequent efforts by CORFO to promote innovation spillovers led to the support of university-based business accelerators and seed money for innovative start-ups. During 2010–2014, even though R&D activity in Chile remained low, PCT patenting efforts increased significantly. However, in October 2019, the country went through its worst social crisis in decades, starting a civil process to change its Constitution and kickstarting an economic crisis. This crisis, forced by previous economic disparity (Edwards Citation2019; Morales Quiroga Citation2021), was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, plunging Chile into a recession with a magnitude unseen since the 1982 monetary crisis (Muñoz et al. Citation2020b; OECD Citation2021).

In sum, we have a country that apparently complies with all KSTE pitfalls in developing countries from González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2015), and also respects all the requirements for the KSTE mechanisms to occur: a strong and stable economy, local support to entrepreneurship from formal institutions, and robust innovation capabilities. However, no substantial growth has been observed at all. This disparity is what allows us to examine rival explanations related to the role of economic incentives and the entrepreneurial ecosystem in encouraging innovation-driven entrepreneurship. With this in mind, we can state the Chilean Paradox: Why does an OECD country, ‘rich’ in innovative entrepreneurs, exhibit such low growth rates.

3.2 Dependent variables

A common pitfall in KSTE studies is the difficulty of measuring venture creation rates based on knowledge spillovers, as it is non-trivial to separate such ventures from firms created from other sources (Qian Citation2018). As most entrepreneurial measures typically correlate with economic growth, there could be some confusion when separating and analysing our phenomenon. A common fix for this in previous studies is to use ‘entrepreneurship in knowledge-intensive sectors’ as a proxy (e.g. Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008; Tsvetkova, Thill, and Strumsky Citation2015)

We selected four different measures for entrepreneurship, as these allow for variation in the grade of knowledge dependence. These are (1) new firms in high-tech industries, defined as ‘firms of professional, scientific, and technical activities’; (2) new firms in the informatics and communication technologies industries (ICT), partly considered as having high knowledge use; (2) new firms in all industries and (4) as a counterfactual, the rest of the industries denoted as ‘low-tech industries’. Low-tech refers to the industry degree of R&D intensity, not to the founders’ capabilities or the extent of human capital. This categorization allows us to see how the rate of knowledge transfer into new ventures varies when shifting from knowledge-intensive sectors to less knowledge-intensive sectors of the economy, allowing us to compare our results with previous literature on developed settings more directly (Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008; Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019). Also, we measured entrepreneurship as a rate instead of a stock, considering both firm entry and exit from the economy to offer a better picture of entrepreneurship over time than just considering the rate of firm entry (Gartner and Shane Citation1995). Considering that emergent economies are rich in necessity entrepreneurship (Valliere and Peterson Citation2009) with higher failure rates and usually not KSTE related, not taking into account the exit rates could generate bias. For example, during an economic downturn, the occurring destruction of jobs would push a percentage of labour into self-employment. In this developing country scenario, this group would probably be less motivated to start a business by an opportunity found in the stock of available knowledge but more due to necessity during harsh times. This increment on entry rates, although real, would not be representative of the phenomenon we are trying to understand, thus we add the exits from the market to control for this. Several other measurements of entrepreneurial activities were also tested (e.g. new business registrations per capita and per GDP) with inconclusive results, so we believe the one selected is the most adequate to represent the phenomenon at hand.”

3.3 Explanatory and control variables

In Acs et al.’s (Citation2009) theoretical model of the KSTE, the knowledge-production function consists of two elements: how knowledge production accumulates regionally and how it is used. Some methods to measure knowledge production from the literature give relevance to the mere presence of public universities (Del Monte and Pennacchio Citation2020), the number of graduate students, and the number of research publications (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005) or academic R&D expenditures (Lendel Citation2010). In our case, we used regional spending in R&D, thereby including different public and private R&D sources like incumbent firms, universities, and non-profits (Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005; Plummer and Acs Citation2014). Regarding knowledge utilization, as it is virtually impossible to measure it in a region, a common way of doing so is by patent count (Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019). When a firm protects its knowledge by registering it as a patent, it takes this knowledge out of the unused pool of knowledge, saving it for the firm to extract its invested value, thus hindering new ventures. (Acs and Sanders Citation2008) expand this idea, showing that more robust protection of intellectual property rights has an inverted U-shaped effect on innovation. That is, stronger patent-protection laws encourage more inventors and investments to develop new ideas, but also reduce the available knowledge in a region for entrepreneurs to exploit, thus affecting new firm rates. Hoping to capture both effects, we controlled for the creation and use of knowledge in a region by patent-count registrations per 1 million habitants and per-capita R&D investment. As knowledge production or patenting takes time from being developed to be available locally for its use or protected in a patent, we lag both variables one year,Footnote6 that way reducing measurement bias.

Apart from knowledge variables, empirical studies on the KSTE have also incorporated control variables, such as market regulations, macroeconomic variables, industry structure, urbanization and institutions (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009; Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2007; Tsvetkova Citation2015), without a strong consensus on which of these are relevant. Simultaneously, other authors have attempted to identify specific factors or characteristics of the surrounding entrepreneurial ecosystem that foster knowledge transfer into new ventures. Some examples are cultural diversity (Audretsch, Belitski, and Korosteleva Citation2019; Audretsch and Belitski Citation2013), related variety and firm heterogeneity (Cainelli and Ganau Citation2019), the creativity of a region (Belitski and Desai Citation2016), and how regional diversity and authenticity (sexual, racial, and social) attract individuals with greater creative capacity to a city or region (Das Citation2016). Along these lines, Qian (Citation2018), borrowing from the entrepreneurial ecosystem literature, develops a theoretical frame of regional environmental factors that are particularly important for the KSTE while excluding other factors discussed the literature. These are: knowledge bases, competition for knowledge, networks, diversity of firms and people, and entrepreneurship culture. This does not mean that the other factors (e.g. access to capital, demand, infrastructure, or leadership) not impact KSTE-born firms, as the ecosystem literature has suggested they do; it means only that these other factors are important to general entrepreneurship but are not particularly important to the KSTE.

Knowledge bases refer to the sources of knowledge (universities and incumbent firms) and entrepreneurs’ absorptive capacity (Qian and Acs Citation2013). As knowledge producers depend on human capital for research and regions specialized in engineering or management tend to have more entrepreneurial opportunities to exploit (Qian Citation2017a), we controlled for both with the percentage of the working force employed in technical, professional, and scientific companies.

Second, how firms compete for knowledge affects the degree of its spillover, as competition in a market among similar firms puts pressure on businesses to innovate as a means to survive and grow (Porter Citation1998). This leads to additional knowledge created by incumbent companies in the region and thus to more knowledge available for entrepreneurs to utilize (Plummer and Acs Citation2014). Simultaneously, more competition forces firms to protect their produced knowledge so they can exploit it themselves, decreasing the spillover effect. The overall effect is typically measured as the inverse of the average firm size in terms of full-time workers (Qian Citation2018).

Third, networks are essential for supporting the transfer of knowledge spillovers to entrepreneurs, with a striking consensus among multiple disciplinary perspectives that network characteristics mediate all resources necessary for entrepreneurial performance (Hayter Citation2013). Strong social connections facilitate new knowledge-based entrepreneurial opportunities being exposed to potential commercialization, acting as critical conduits for information, resources, and new knowledge and connecting entrepreneurs with funders, researchers, and advisors. These individuals can act as advisors, helping entrepreneurs determine the economic value of new knowledge, thereby addressing some of the KSTE’s conceptual concerns related to endogenous growth theory (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009). As agglomeration studies have claimed that information moves quickly across shorter distances, we controlled for this with a variable representing regional population density in logarithm form as it provided more data variation (Audretsch and Belitski Citation2013).

Fourth, the degree of the diversity of related industries and people also contributes to knowledge-spillover entrepreneurship. As an approximation for the regional diversification of the economy, we included Bishop and Gripaios’s (Citation2007) entropy measure,

where Si is the share of the i’s four-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) category in a region’s total employment, as there are n different four-digit categories. The index value is zero if employment is concentrated in one sector and maximized at ln(n) if employment is diversified across all sectors of the economy. A higher and significant parameter would support that a Jacobian spillover is more critical to growth, as unrelated firms take advantage of being spatially closer.

Regarding control variables, we include regional GDP per capita growth (%) to control for differences in regional economic growth, the regional human development level (HDI) for differences in inequality and quality of life, and the distance between each regional and metropolitan capital (Santiago) for spatial considerations. This allows us to control for the country’s particular shape and size, which makes communication, transport and, noticeably, knowledge flows, quite difficult when dealing with distant regions (i.e. Northern and Southern ones). Finally, we take into account changes in the barriers to entrepreneurship. In 2013, Chile implemented the ‘Your Company in One Day’ initiative to ease paperwork and lower the time and capital costs of starting a business from 40 to only one day. Reducing entry barriers should increase firm-creation rates across industries (Klapper, Laeven, and Rajan Citation2006), so we expect this variable to explain part of the entrepreneurial rates. Thus we add a dummy for the years of this legislation being implemented.

3.4 Methodological approach

Our approach is based on the empirical estimation strategy adopted by Acs et al. (Citation2009), which explained the core of the KSTE through the following function:

where

i: Regions

t: Years

ENT: Entrepreneurial outcome

KSTOCK: Knowledge stock

KU: Knowledge utilization

BARR: Barriers to entrepreneurship

Z: Control variables

u: Error term

Our dataset comprises yearly data from Chile’s 15 administrative regions,Footnote7 similar to the NUTS2 category of administrative regions in Europe (Eurostat Citation2015), from 2010 to 2019, with a sample size of n = 135. Each region has a distinctive capital in which most human and technical capabilities are concentrated, and regional policies for R&D support are coordinated. presents the details of each variable and its parametrization. Data was obtained from public sources such as the National tax service’s administrative data (SII), the National Statistics Institute (INE), the Central Bank of Chile (CBC), and the National Patent Office (INAPI). The HDI was obtained from Global Data Lab (Radboud University Nijmegen Citation2022), and the GINI was calculated from the CASEN Survey (Ministry of Social Development Citation2015).

Table 1. Variables and data sources summary.

Previous studies on Chile’s entrepreneurship and innovation characteristics have presented some interesting facts to consider. First, there is a high level of persistence in the country’s most and least entrepreneurial areas (Espinoza et al. Citation2019; Oyarzo et al. Citation2020), suggesting that regional entrepreneurship drivers do not change much year to year. This suggests possible time dependence and autocorrelation of the entrepreneurial activities between years. The Wooldridge test statistics for autocorrelation in panel data confirm time dependency in the overall and low tech economy, but not in the ICT and HT sectors. To control this effect, we add a standard first-order temporal autoregressive term of entrepreneurial activity to our model.

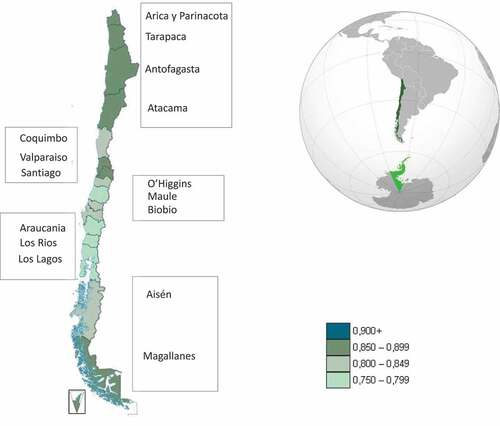

Second, there seems to be some spatial dependence between regions as one area’s entrepreneurial success positively affects its neighbours’ entrepreneurial performance. As not considering spatial dependence and regional spatial characteristics in our model could bias our results, we drew from a Ministry of Science classification and clustered regions with similar geographical, cultural and social characteristics into macrozones, detailed in .

Figure 2. Map of Chilean regions by HDI Level in 2019, Adapted from Nijmegen Center for Economics (2022). Boxes represent macrozones classifications based on a previous one from the Science Ministry of Chile. While the capital’s metropolitan region is not part of any macrozone, we choose to add it to the center macrozone. That way, joined with the Valparaiso Region, represents Amorós, Felzensztein, and Gimmon (Citation2013) ‘Core region’ of the country, defined with higher productivity capabilities. These macrozones also reflect region-specific geographical and cultural characteristics: desert and andine influences in the north, flat valleys and farm life in the centre, forests and Mapuche influences in the south, then European in the lakes Patagonia macrozones in the southern country) .

Because we used two levels of analysis (regions and macrozones), we analysed the data using HLM methods. Multilevel modelling is appropriate when data is hierarchically structured. In our case, regions belong to a determined macrozone (Aguinis, Gottfredson, and Culpepper Citation2013; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal Citation2006). With standard multivariate methods, the assumption of independence of observations could be violated (Hofmann, Griffin, and Gavin Citation2000). The use of HLM helps improve estimations compared to other multivariate procedures because it reduces the risk of Type I errors from not acknowledging the existence of a higher level (macrozone) and treating all variables as if they were observed at the individual level (Huta Citation2014). Consequently, using conventional single-level regression analysis could increase the possibility of ‘false positives’ due to underestimating the standard errors because of their non-normal distribution. To test this method’s validity, we compared the Akaike information criterion (AIC) of our hierarchical model against a similar one without the hierarchical levels (Bozdogan Citation1987), finding that the former fits the data better.Footnote8 To controlling for other spatial effects, we also check for spatial autocorrelation using Moran’s I statistics test. Results () show no regional dependence except for some particular years, thus discarding any additional effects needed to control. One possible explanation is that although there is evidence for spatial dependence in municipalities (as Espinoza et al.;Citation2019 suggests), this does not translate as easily to regions.

Table 2. Moran’s I test for spatial autocorrelation.

Additionally, we tested for heteroskedasticity with a Breusch-Pagan test, needing to add robust errors to our model (Green Citation2018). Finally, a pairwise correlation () revealed some significant correlations between our explicatory variables. Nonetheless, the fact that some or all of the predictor variables are correlated among themselves did not, in general, inhibit our ability to obtain a good fit, nor did it tend to affect inferences about mean responses or predictions of new observations. Also, the variance inflation factors (VIFs) for all the variables are below the usual benchmark of 10, thus indicating that multicollinearity is not an issue. Results are available by request.

Table 3. Pairwise correlations.

The specifics of the endogenous firm-formation mechanism proposed by the KSTE entail a circular dependence of business entry on knowledge production and of knowledge production within firms on business entry. This dependence could lead to an endogeneity problem in the empirical estimation (Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019). However, instrumentalizing the knowledge variable with the number of regional researchers per capita and using Anderson’s under-identification test did not show any endogeneity. For further testing, an alternative standard method to solve circular causality in the literature is to use Blundell and Bond’s (Citation1998) ‘system GMM’. We tested the instruments’ overall validity with Hansen’s J test of over-identifying restrictions, not finding evidence to validate this method.Footnote9 A possible reason for this lack of endogeneity could be contextual characteristics: As in our case, most R&D spending comes from public funding, thus more dependent on national economic policies than created firm rates, reducing the circular dependence. As an example, in 2018, only 30% of national R&D spending came from private for-profit funding.Footnote10

Finally, we defined our working model as

where m is the macrozone, represents the time effects,

ecosystemic conditions and

+

are the macrozone and individual region-level random residuals.

4. Results

The main estimation results for all models are in . First and foremost, knowledge production has heterogeneous effects on business formation depending on the analysed industry, not giving conclusive support for H1. The only sector with a significant and positive relationship is the high-tech industry. The rest of the entrepreneurial rates are not dependent on R&D spending. While European evidence supports the KSTE in all economic sectors (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009; Audretsch and Keilbach Citation2008; Audretsch and Lehmann Citation2005), and American or Italy evidence only supports the theory on high-tech and ICT industries (Colombelli, Orsatti, and Quatraro Citation2021; Tsvetkova and Partridge Citation2019), in our developing-country context, we only found support for high-tech entrepreneurship.

Table 4. HLM results.

Second, the percentage of the labour force in knowledge firms negatively explains general and low-knowledge firm-creation rates, not supporting H2. This could be explained because developing economies tend to have a larger share of self-employed, necessity-driven entrepreneurs, usually characterized by low-skill, basic subsistence ventures (Z. Acs Citation2010; Almodóvar-González, Fernández-Portillo, and Díaz-Casero Citation2020; Amorós et al. Citation2019). If one region has data showing a large percentage of its workforce inside high-knowledge firms, then it would imply that they are concentrated mainly at big incumbent firms, thus reducing the raw number of new firms in the overall market.

Third, we found a significant and negative effect of knowledge use on firm creation, consistent with the previous literature (Z. J. Acs et al. Citation2009), except for the ICT sector. Of course, this does not mean that patent production should be discouraged, but instead that, in our model, a past patent registration represents an idea that is no longer available in the market space, thus mediating the number of new companies born from that knowledge spillover. Also, per definition, unused knowledge cannot be considered an innovation yet as it must be first introduced to the market. Moreover, as we measure economic development based on the number of new per-capita companies, and not on increase of incumbent firms’ size, a firm protecting a newly developed product and introducing it to the market (with its consequent profits) is not measured in our model.

Regarding our ecosystem variables, first, there is no ecosystem effect on ICT firm creation, giving more evidence to the non-existence of KSTE firms in this sector. Second, firm diversity has a positive and relevant impact on new high-tech firm creation, supporting the idea that Jacobian spillovers are more relevant for new firm creation than Marshallian spillovers (Baltzopoulos, Braunerhjelm, and Tikoudis Citation2016), and thus validating H3. This finding is in line with current diversity discourse, which emphasizes the effect of unrelated diversity on growth (Rosenzweig Citation2017) – namely, technology taken out of its original context and adapted to an entirely different technological context. This concept suggests that a region’s ability to commercialize knowledge intended for a very different technological context bestows competitive advantage and thus economic growth. Third, population density negatively affects the creation rates of firms in general and low-knowledge new firms in particular, challenging the core assumption of an urban efficiency advantage. It seems that the non-linear diseconomies of scale in urban environments, such as congestion costs, pollution, or oversupply of labour, and higher living costs could offset the positive effects of networking on spillovers (Dijkstra, Garcilazo, and McCann Citation2013; Folta, Cooper, and Baik Citation2006).

The economic-cycle stage, measured as the variation of regional GDP in our study, has different effects depending on the analysed sector. Positive GDP growth was expected to impact firm-creation rates, as good economic conditions help foster new business development. However, we did not find any effect on the high-tech sector, probably because this sector is less dependent on the economic cycle and more dependent on international markets or long product-development cycles. Finally, reducing barriers to entrepreneurship (i.e. the ‘Your Company in One Day’ initiative) positively affected firm creation in all industries, supporting H4. The effect of this legislation is ten times stronger for general entrepreneurship and the low-tech sector than in the high-tech sector. This supports previous literature, as costly regulations hamper new firm creation, especially in industries that should naturally have high entry (Klapper, Laeven, and Rajan Citation2006).

4.1 Alternative knowledge model

According to our initial results, the percentage of knowledge professionals in a region (i.e. absorptive capacity) is not statistically significant in explaining high-tech firm creation, contradicting prior literature (Qian and Acs Citation2013). To understand the dynamics of human capital in high-tech companies, we propose a variation of our previous model. During the year 2013 of our dataset, there was a sharp decrease in entrepreneurship entry barriers as the ‘Your Company in One Day’ initiative started. Because of this, knowledgeable risk-averse human capital now had less uncertain conditions for entrepreneurial spawning. To analyse the full effect of this policy on human capital, we propose a model in which we add a cross-interaction between these two variables.

As shown in , the interaction effect is positive and significant, and the human capital variable by itself maintains its insignificance. This finding suggests that in our case study, human capital only affects firm creation rates when the level of bureaucracy allows it and not otherwise. Only after the policy went into effect did firm-creation bureaucracy stop inhibiting employees’ transition to entrepreneurship. Another relevant result is the lack of significance of R&D for high-tech firm creation after adding the interaction factor, capturing all the variables’ previous effects. It appears that only when considering the full effect of human capital on entrepreneurship does R&D stop being relevant in our model, giving more relevance to ecosystem characteristics, such as human capital and firm diversity. This finding supports the importance of each region’s specific ecosystem characteristics in explaining the conditions under which the KSTE mechanisms apply and the degree to which they function.

Table 5. HLM results, proposed model.

From an ecosystem standpoint, Acs (Citation2010) proposes the importance of the bottleneck effect for entrepreneurship development as the weakest link of an ecosystem hinders its full capability. In our case, it seems to be that the bureaucratic process for starting a new firm was adding uncertainty to entrepreneurs’ decision-making and thus blocking the KSTE mechanisms, implying that institutions need to be strengthened before entrepreneurial resources can be fully deployed. Finally, in appendix A, we show how the explicative power of R&D spending diminished when we included the ecosystem and controls variables in the model.

4.2 Robustness analysis

The results presented so far are preliminary because we have not considered all data specificities or alternative proxies for our variables. In this section, we perform three types of robustness tests to check whether taking these specificities into account changes our findings. We provide selected results (Overall economy and High Tech) of alternative specifications in .

Table 6. Robustness analysis.

First, we repeat our previous model without including the Metropolitan Region of Santiago, as its bigger wealth, political and human capital concentration could skew our findings. Columns (1) through (4) show that the results do not differ from our original model.

Next, we interchanged the barriers of entrepreneurship variable with the ‘Starting a business Score’ from the World Bank’s ‘Ease of doing business index’. We believe that this variable could better capture year-to-year changes in legislation regarding entry barriers to entrepreneurship than a binary about one particular policy. Columns (5) through (8) show that these results do not vary much from our original model.

Additionally, many economic and financial time series exhibit trending behaviour or nonstationary in the mean. If data are trending, then some form of trend removal is required. Two common trend removal or de-trending procedures are first differencing and time-trend regression (Zivot and Wang Citation2017). Considering this, we test our data for stationarity with the Harris–Tzavalis unit-root test to avoid producing spurious regressions (Sweidan Citation2021). Our results show that all four ecosystem variables and the HDI level are incremental, which was expected as the regional entrepreneurial ecosystems have improved in the last decade (Bustamante, Mingo, and Matusik Citation2021). To correct this effect, we differentiated all ecosystem variables one time, plus competition that needed to be differentiated a second time to become stationary variables. The results in columns (9) through (12) show some interesting findings. First of all, firm diversity losses all explanatory power, suggesting that further studies are needed to give robustness to this finding. Second, knowledge stock losses significance into explaining high-tech business creation, contradicting the previous results. However, when adding the moderating effect between knowledge and barriers to entrepreneurship (Barr*Knowledge Class), it becomes significant again, with a high significance of p < 1%. In this specification, it seems that the moderating effect of the barriers to starting a business on the absorptive capacity of a region is effectively hindering the positive effect of knowledge stock on new ventures

5. Discussion

Our study centres on how knowledge is transferred to create new firms in a developing economy context. Based on our results, knowledge spillovers are only used in sophisticated firms (e.g. technological firms) and not for ICT, general or low-knowledge entrepreneurship. At least theoretically, the ICT sector should be partly dependent on knowledge, so some transfer of knowledge should occur. However, after reviewing the empirical results, this sector’s activity is so underdeveloped and concentrated in its capital city that the data variability prevents us from obtaining significant results, serving us as an example of how little dependence is growth on knowledge production. If we switch industry sectors from complete to partial dependence on knowledge, the knowledge effect on growth disappears.

Given the conditions that the KSTE asks for, the case of Chile is particularly interesting to study because, despite all the expectations that it should already be a developed country, it is still underdeveloped. Accordingly, to explain this, we go back to the core arguments of the theory and its validity for our case: (1) growth and knowledge are endogenous, (2) knowledge must accumulate in a region, and (3) entrepreneurs act as knowledge filters.

First, firms from developing economies have fewer incentives to invest in R&D as they have less capacity and efficiency in patent production (Fu and Yang Citation2009). According to Amorós et al. (Citation2019), this lower capacity and efficiency may be related to three issues: a disconnect between R&D and new venture creation, causing inappropriate mechanisms for technology and knowledge transfer; scarce use of new technologies in the majority of new business models and ventures; and a lack of consistent policy and public programmes that support innovative (technology-based) new firms. An older analysis of Chile’s innovation system is even more severe, as empirical results showed that Chilean firms’ productivity in the 90 ‘s was not affected by innovative results nor by research expenditures in the short-run (Benavente Citation2006). This trend has been corrected only recently with mixed results (Álvarez, Bravo-ortega, and Zahler Citation2015; Aroca and Stough Citation2016; Crespi et al. Citation2020). If companies do not have incentives to invest in R&D, they will have to find other sources of innovation to maintain long-term competitiveness. This can be in alternatives more prone to developing countries, such as engaging in imitative innovation (Minniti and Lévesque Citation2010) importing foreign technology (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015; Montégu, Pertuze, and Calvo Citation2021), intermediate goods (Kasahara and Rodrigue Citation2008) or learning-by exporting (Bravo-Ortega, Benavente, and González Citation2014). A low level of investment in R&D will lead to constraints in knowledge spillovers with the subsequent effect of limited new ventures born from the KSTE.

Second, studies from the international business literature have stated that when emerging economies promote innovation, one of the secondary effects is incremental foreign participation in such activity. For instance, Matusik, Heeley, and Amorós (Citation2019) show that spillovers are less likely to stay local when ownership of an invention is foreign. While foreign ownership of an invention is associated with spillovers happening outside the host country, local ownership may allow for a greater transfer of knowledge about inventions to the local context, providing a foundation for creating new knowledge that builds upon those ideas. As previously discussed, González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2015) mention the importance of foreign direct investment knowledge spillovers when there is a lack of local knowledge production in a home country. If R&D is produced mainly by foreign firms, there will be fewer knowledge spillovers to local entrepreneurs and fewer new firms born of the KSTE.

Another possible explanation comes from Tsvetkova and Partridge (Citation2019), who show that when shifting the grade of knowledge use, the KSTE-based explanation of business entry is not always consistent with firm-formation patterns. For example, separating the US computer and electronics high-tech sector into goods and services companies reveals that spillovers only occur in the latter. They reason that it is easier to protect knowledge in the goods sector than in the services sector, by patenting tangible innovations or establishing more restrictive non-compete clauses in employment contracts. Based on this argument, as developing economies tend to focus more on producing goods than services (Rubalcaba 2013), higher appropriability rates from incumbent firms can be expected, which in turn reduce available knowledge for accumulation in a region.

Third, according to the risk and uncertainty literature, given two employed high-knowledge entrepreneurs with the same risk tolerance, the one in a riskier setting will need a higher expected utility to switch from his or her full-time job’s stability to the uncertainty of entrepreneurship (Cressy Citation2000; Kan and Tsai Citation2006). Given the higher uncertainty in developing economies related to their more fragile institutional frameworks (Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson Citation2005), entrepreneurs in a developing country will need higher expected utility levels to start a business, ceteris paribus, compared with a developed setting. Thus, they will have a lower chance of switching due to their alternative costs (Earle and Sakova Citation2000), thereby reducing regional firm-creation rates. Of course, this logic does not apply to low-knowledge entrepreneurs as they tend to be pushed into self-employment instead of choosing to do so. resumes the previous core arguments of the KSTE theory and its failing state.

Table 7. KSTE core arguments, restrained by development countries’ characteristics.

5.1 The Chilean paradox

Coming back to our paradox, we can now explore how it behaves with the previous KSTE assumptions and confer some insights that may explain our results. From the knowledge supply side, despite all the policy efforts to create and promote knowledge from R&D centres and universities, we could not find any endogeneity between firm creation rates and knowledge production. This suggests the low knowledge spillovers from being created from those firms. Alternatively, they do not conduct R&D, and if they do, they manage to appropriate their associated results effectively. From the entrepreneur supply side, despite the population’s positive attitude towards entrepreneurship (Guerrero and Serey Citation2020), the type of entrepreneurs who are needed to start high-knowledge ventures – be it from uncertainty, opportunity costs, or entry barriers – are not appearing in high enough rates for the development of high-knowledge ideas and their transformation into ventures to occur. Put this all together, and it reveals a scenario in which the country addressed both the formal and informal institutions needed to foster an entrepreneurship culture, which would have generated the logic required for endogenous growth based on entrepreneurship as a pillar of the economy. However, this growth was not seen as the type of entrepreneurship generated in Chile was not precisely the type that produces an economic surplus but was instead more precarious with little added value. Therefore, it disarmed this logic.

Although we consider Chile a transition economy, which may apply to the country as a whole, some regions (especially the peripheral ones) are far away from being a developed areas. The high inequalities between regions could be affecting the rationale under our study.In fact, Chile is one of the most concentrated countries in the world, as around 40% of the population lives in the capital city, Santiago, which produces about 45% of the GDP. At the same time, most policies promoting welfare focus on people, thus spatially blind. Increasing brain drain effects on the capital further complement this inequality (Aroca and Eberhard Citation2015).

This failure occurred because the country built a culture around entrepreneurship, thinking that more entrepreneurship was better, but this reasoning did not pan out. The country does not need more low-quality entrepreneurship but instead better entrepreneurship (Shane Citation2009) that generates economic growth. The problem in Chile is that the country saw entrepreneurship as the generation of companies with a purely economic vision and did not understand the fundamental nature of entrepreneurship (Kuratko Citation2005).

6. Implications

Prior studies have stated the need to analyse the underlying assumption behind KSTE to deeply understand why some countries have failed in their transition from an emerging economy to a developed one (González-Pernía, Jung, and Peña-Legazkue Citation2015). Based on our findings, we have identified some boundary conditions that seem to restrict the effectiveness of KSTE in our developing country (i.e. Chile), despite accomplishing the apparent appropriate requirements that this theory needs to facilitate for knowledge spillovers to flow. One of the things commonly requested for theories to be of value is their predictive power (Makadok, Burton, and Barney Citation2018). Accordingly, several empirical studies have been published around KSTE, but only considering developed countries. By testing this theory in a developing country, we aim to evaluate the boundary conditions behind the basic assumptions embraced on the KSTE. We consider Chile a particularly fruitful case analysis because it is quite similar to some developed countries in macro-level conditions. Indeed, as we have previously mentioned, Chile was one of the first emergent countries to be added to the OECD membership. Accordingly, by being so similar in some aspects but not so much in others, we can explore the theory and its implicit assumptions in terms of boundary conditions through this case analysis. Therefore, within this study, we provide some insight into the reasons that may explain this phenomenon. It is not about Chile as unique, but its features that make it an especially suitable case for testing the KSTE.

This allows us to generalize our findings, not only to developing countries but to the whole theory. For example, we have identified under what conditions skilled individuals will pursue high-tech opportunities. While the KSTE posits that entrepreneurial opportunities emerge from a society’s investment in human capital, research, and development (Audretsch, Keilbach, and Lehmann Citation2006), we evidenced that when linking human capital with Schumpeterian opportunities, the local bureaucracy level plays a moderator role. In other words, we provide insights about the ‘when’ or ‘under what conditions’ knowledge spillover’s flow of knowledge resources and capabilities from one decision-making entity benefit skilled individuals to enact high-tech entrepreneurial ventures.

Finally, we have identified a core driver of KSTE in our developing economy, as industry diversity (heterogeneity in capabilities and firm industries) plays a key role as a source of knowledge for high/tech firms to be developed aligned (Agarwal, Audretsch, and Sarkar Citation2010). This finding is aligned with Griliches’s (Citation1992) review of the empirical literature on R&D expenditures, stating that the significantly higher social to privates rates of return to R&D investments can be attributed mainly to the high levels of R&D spillovers across organizations.

Overall, these results provide some potentially valuable insights that may contribute to the contextualization of KSTE in developing economies. First, at an abstract level, the whole rationale of the theory needs to include more dimensions that incorporate the local reality and how this may restrict or enhance knowledge spillovers. Second, in order for knowledge to be transferred, specific conditions are requested, turning this process into a complex issue. In this sense, efforts on bureaucracy reduction, increment of regional firm diversity, or highly centred entrepreneurship policies must be focussed on particular markets or micro-groups of entrepreneurial activity. For the case of Chile, policymakers must focus on fixing the previously detailed elements necessary for the KSTE to occur before blindly expending more funding in knowledge creation via R&D or innovation fostering programmes. For other developing countries with less robust institutions, they will need first to work on the basic requirements for entrepreneurship and innovation to occur, like IP protection, strong rule of law, or property rights. Only then they can start improving the related KSTE requirements stated in this research.

One example of this is presented by Romaní, Atienza, and Amorós (Citation2013), who analysed a national policy for developing business angel networks (BANs) in Chile. In contrast to the experience of Europe (Mason, Citation2009; Mason and Harrison, Citation2001) and Asia (Botelho, Citation2005), where the support for the formation of angel networks sought to reduce the equity gap, in Chile, the objective was to strengthen innovative entrepreneurs. However, the difficulties the BANs faced in finding attractive projects, as the entrepreneurs did not present good projects, came with high rejection rates and difficulty in reaching the BANs’ target objectives, weakening its sustainability. After the policy ended, and despite the programme having a national focus, only the angel networks in the capital survived, having failed in the rest of the country. The main issue was that the policy only focused on financing the investors, where no direct policies for developing the preliminary conditions for the emergence of quality entrepreneurs were considered. To further extend this point, we can apply our ideas in a related knowledge-spillovers case study. In 2012, under the belief that Silicon Valley innovativeness could be replicated with the ‘right recipe and recommendations’ (Albornoz and Pérez Ones Citation2020), Ecuador developed in the middle of the mountains the innovation-focused city of Yachay. This would take advantage of locally produced human capital and the diversification agglomeration dynamics of its technological park to kickstart a technological revolution in the country. However, by 2018 the industrial park was still in the planning stage, being declared as failed (Gómez-Urrego Citation2019). Under this study’s logic, one possible reason for this project to fail could be its focus on fostering knowledge production and expecting its subsequent spillovers without developing first the primary conditions for this knowledge to transition into products and new ventures effectively. Some missing conditions were: a lack of human capital (Chavez and Gaybor Citation2018), firm’s missing innovative capabilities (INEC, Citation2016) and a national productive structure based on commodity exportations and dependent on industrialized imports (Gómez-Urrego Citation2019). In sum, the previous evidence suggests that just spending on the infrastructure without focusing first on creating the conditions for making firms effectively produce knowledge would end up with just a ‘great white elephant’ (Chavez and Gaybor Citation2018, 246).

7. Conclusions