ABSTRACT

Because entrepreneurship is socially embedded and influenced by societal discourses, this study combines content and discourse analysis to analyse entrepreneurship policy texts in The Netherlands and Kosovo. These discursive threads, as portrayed and produced by policy texts, reveal discursive nuances across these two contexts that each accommodate entrepreneurship in their own ways. Discursive threads within entrepreneurship policy texts, pertaining to (economic) power, protectorates, and enterprises, reveal constraints on entrepreneurial agency by enforcing a limited view of entrepreneurship. In a transitioning economy (Kosovo), discursive threads seem more rigid than in an advanced economy (The Netherlands). Policy texts in the former setting attribute entrepreneurial achievements to government intervention; in the latter, the role of government appears diminished and complemented by other explanatory factors. Policy texts in the advanced economy also exhibit a broader understanding of entrepreneurship, such that they link it with societal issues, instead of reducing the phenomenon to an economic logic, as is the case in the transitioning economy. These findings advance a more nuanced understanding of the relations among discourses, ideology, entrepreneurship, and policymaking, by bringing differences across social contexts to the surface, as well as linking policymaking to a contextual view on entrepreneurship.

Introduction

Policymakers direct attention towards entrepreneurship, as a potential force for economic development, and establish policies to encourage entrepreneurial initiatives. But such efforts also have far-reaching consequences, not least in terms of how they define how entrepreneurship will be understood in that society. A seemingly general belief shared by policymakers is that entrepreneurship fosters economic growth, competitiveness, and employment (Audretsch, Keilbach, and Lehmann Citation2006; Anderson Citation2015), so they often express conventional views of entrepreneurship in their political agendas, using rhetoric bound to the promise of economic progress (e.g. Perren and Jennings Citation2005; Da Costa and Saraiva Citation2012; Anderson Citation2015). This emphasis on conventional forms of entrepreneurship, related to economic progression (e.g. Calás, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009), thus appears in discursive threads related to entrepreneurship and signifies the dominant meanings ascribed to it, which in turn produce the realities surrounding this phenomenon (Anderson and Warren Citation2011).

A notable source of such discursive threads is entrepreneurship policy texts (Perren and Jennings Citation2005; Da Costa and Saraiva Citation2012). The language used in policy texts tends to govern subsequent policy actions, with essential impacts on a society’s understanding of and interest in entrepreneurship (Anderson and Smith Citation2007; Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021). Accordingly, policy texts regularly get evaluated, in terms of their effectiveness in stimulating entrepreneurial activity (Ahl and Nelson Citation2014), yet little attention has focused on the discursive threads they inevitably produce (Perren and Jennings Citation2005) and the consequences of such threads. Nor do we have a clear sense of the discursive nuances that might arise, due to different sets of meanings ascribed to entrepreneurship in various contexts (Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017). Because entrepreneurship clearly is socially embedded and influenced by societal discourses (e.g. Anderson and Smith Citation2007; Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017; Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021), social contexts that differ in their views, attitudes, and behaviours towards entrepreneurship (Smallbone and Welter Citation2001) must evoke distinct outcomes. Research is needed to identify such differences in context; we address this need by raising a key research question: What discursive threads are produced by entrepreneurship policy texts in distinct settings (The Netherlands and Kosovo), and what differences do they evoke?

This study contributes to a nuanced understanding of discursive threads of entrepreneurship in policy discourse, as well as the discursive nuances between two contexts that accommodate entrepreneurship in disparate ways. By combining content and discourse analysis techniques, we analyse entrepreneurship policy texts in The Netherlands and Kosovo and thereby (1) identify discursive threads portrayed and produced by these entrepreneurship policy texts, (2) establish the discursive nuances between the two contexts, and (3) offer some possible explanations for the differences. The three discursive threads portrayed and produced by these entrepreneurship policy texts refer to discourses of (economic) power, protectorates, and enterprise. They are more dominant and rigid in the transitioning economy (Kosovo), characterized by institutional voids and moderate economic and social welfare, than in the more economically and socially developed context (The Netherlands). In outlining the links among discourses, ideology, entrepreneurship, and policymaking, we highlight differences in entrepreneurship discourses across different social contexts, which helps connect policymaking efforts to a contextual understanding of entrepreneurship (Smallbone and Welter Citation2001, Citation2003). In a transitioning economy such as Kosovo, characterized by an ‘unstable and hostile … external environment’ and moderate economic and social welfare (Smallbone and Welter Citation2001, 249), entrepreneurship is construed as a means to achieve economic growth. In an advanced economy like The Netherlands, the discourse of economic growth appears but coexists with broader considerations, such as those related to social change. Furthermore, the policy discourse in Kosovo explicitly constructs entrepreneurial achievement as a result of governmental intervention, whereas in The Netherlands, the role of the government appears reduced and shared with other factors that also influence entrepreneurship, such as academic research.

Theoretical background

Entrepreneurship discourses and policy texts

Various studies rely on policy texts to explore entrepreneurship discourses and positioning in general terms. For example, Ahl and Nelson (Citation2014) compare the positioning of female entrepreneurs in entrepreneurship policy applied over two decades in Sweden and the United States. They find inequalities even in policies that claim to help female entrepreneurs, because they become positioned as ‘other’. Pettersson et al. (Citation2017) emphasize the importance of analysing discursive threads in this context, because female entrepreneurs often are explicitly targeted by policies that claim empowerment goals, yet the policies achieve the opposite effect. The outcomes thus depend on the premises that underlie the policies.

Among studies of entrepreneurship and discourses though, we find little consideration of discursive threads of entrepreneurship, which can denote the dominant meanings ascribed to entrepreneurship (Anderson and Warren Citation2011). These discursive threads, which typically build on assumptions (Wiklund, Wright, and Zahra Citation2019), portray and (re-)produce patterns of meanings that influence a society’s understanding of and interest in entrepreneurship (Anderson and Warren Citation2011). They become relevant and possibly problematic if they produce meanings about entrepreneurship that are widely accepted (Ogbor Citation2000). The discourses then become containers and indicators of ideology (Anderson and Warren Citation2011), and the understanding of entrepreneurship they produce is likely flawed (Tedmanson et al. Citation2012). Eventually, as Rehn (Citation2008) argues, discursive threads become established as final facts, even though they reflect ideologies rather than ‘reality’, without ever being contested (Achtenhagen and Welter Citation2011).

Such acceptance tends to be more likely if the language used to portray and produce the discursive threads is articulated by people in power (Wodak and Busch Citation2004). That is, the dominance of discursive threads depends on the source of language, and Ahl and Nelson (Citation2014) argue that people draw on discourses that are more institutionalized and powerful. For example, entrepreneurship policy texts usually are written by people in power, who can shape conceptions of entrepreneurship by ascribing meanings to the phenomenon (Perren and Jennings Citation2005; Da Costa and Saraiva Citation2012). The precise words used in entrepreneurship policy texts define the development of this phenomenon, steer how people think about entrepreneurship, and influence their behaviours (Gartner Citation1993). As Tedmanson et al. (Citation2012, 536) argue, entrepreneurship even can function as a political ideology that shapes public policy in ways that serve ‘economic (capitalist) ends’. Such entrepreneurship policies likely exclude unconventional considerations about entrepreneurship and its links to key social issues, such as its potential benefits for individual transformation (Tobias, Mair, and Barbosa-Leiker Citation2013) or emancipation (Goss et al. Citation2011; Jennings, Jennings, and Sharifian Citation2016). It also would neglect the risk of undesirable social consequences, such as increased regional inequality (Lippmann, Davis, and Aldrich Citation2005) or efforts to preserve a status quo (Verduijn and Essers Citation2013; Hjorth and Holt Citation2016).

The meanings attributed to entrepreneurship and related policies likely are context-specific (e.g. Smallbone and Welter Citation2003; Perren and Jennings Citation2005; Dodd, Jack, and Anderson Citation2013). For example, Mason, Moran, and Carey (Citation2019) identify contextual policy differences in the social enterprise policies of the United Kingdom and Australia, through a comparison of each country’s policy corpus with ‘everyday’ language. The U.K. social enterprise policies exhibit a stronger emphasis on work and employment, which aligns with its public policy, which linked social enterprise to local development. In Australia, market-oriented categories instead have specific relevance in social enterprise policy. As their comparative policy analysis reveals, such divergences between countries can lead to different regime types and outcomes.

Dodd, Jack, and Anderson (Citation2013) also emphasize that entrepreneurship is a socially constructed concept, such that its meanings and related behaviours vary internationally. Therefore, they insist on viewing entrepreneurship in its social context, to reflect the strong differences in conceptualization across nations. Smallbone and Welter (Citation2001) also specify the distinctiveness of entrepreneurship that results from countries’ different stages in their transformation towards market-based economies. According to Anderson and Ronteau (Citation2017), the discursive nuances of entrepreneurship stem from the significant differences of this phenomenon across contexts. In turn, cross-context studies (e.g. Ahl and Nelson Citation2014) appear necessary to understand different meanings, as influenced by societal discourses (and vice versa). Instead, entrepreneurship policy texts tend to be evaluated solely according to their effectiveness for stimulating entrepreneurial activity (Ahl and Nelson Citation2014). The discursive threads they produce – and the possible consequences, in terms of establishing a flawed understanding of entrepreneurship (Ogbor Citation2000; da Costa and Saraiva Citation2012) or revealing discursive nuances that reflect differences across contexts (Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017)—get regularly ignored. By studying discursive nuances, we seek to determine how different understandings are constructed in different contexts for entrepreneurship (Dodd, Jack, and Anderson Citation2013) and depict the role of the context in the relationships among discourse, ideology, entrepreneurship, and policymaking. We elaborate on our methodological approach hereafter, to establish how we obtained our findings.

Methodological approach

From a social constructivist perspective, we propose that discursive threads are constructed through language, such that they produce and represent a set of meanings related to entrepreneurship (Anderson and Warren Citation2011). Language shapes realities, including that of entrepreneurship, according to entrepreneurship policy texts (Dodd, Jack, and Anderson Citation2013). Language and context also diffuse ideas and embed ideologies (Perren and Sapsed Citation2013). Our methodological approach aligns with a proposition by Wodak and Busch (Citation2004) that language gains power through its use by influential people. The language ‘produced’ by politicians and policymakers likely portrays and produces entrepreneurship discourses, so we use entrepreneurship policy texts written by people in power, who can influence certain discourses with their actions.

As we have noted previously, analysing and revealing discursive threads is imperative for gaining a nuanced understanding of entrepreneurship (Jones and Spicer Citation2009; Ogbor Citation2000), because it reveals taken-for-granted norms, ‘ideologies, dominant assumptions, grand narratives, samples and methods’ (Tedmanson et al. Citation2012, 532). Ogbor (Citation2000, 629) calls for studies of how ideology has ‘contaminated’ entrepreneurship discourse, to make it ‘discriminatory, gender-biased and ethnocentrically determined’. Such studies need to challenge taken-for-granted assumptions, such as the ‘ideologized tale of optimism associated with entrepreneurship’ (Verduijn and Essers Citation2013, 612).

Efforts to analyse entrepreneurship discourses often rely on content or discourse analyses (e.g. Ahl and Nelson Citation2014; Marsh and Thomas Citation2017); we combine a content analysis based on text mining with discourse analysis (Stubbs Citation1992; Stubbs and Gerbig Citation1993; Caldas-Coulthard Citation1993; Hardy, Harley, and Phillips Citation2004; Hopf Citation2004; Orpin Citation2005) to reveal dominant discourses related to entrepreneurship in policy texts. An effectively, rigorously conducted discourse analysis can reveal regionally and socially embedded processes at the interface of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurship support. It thus is particularly relevant for assessing entrepreneurship policy texts and the discourses they reflect and produce, because this technique regards data as productive rather than representational (Ahl and Nelson Citation2014). With a discourse analysis, we can focus on what the content is and on ‘what it does, what is included and what is not, what is implied and what is asserted’ (Ahl and Nelson Citation2014, 9). In turn, we gain a sense of the underlying meaning of texts, embedded in their social and historical context, and can understand the societal processes that these documents shape, particularly in terms of the relationship between language and ideology (Orpin Citation2005). However, discourse analysis also has been criticized for including a relatively small number of texts, which may limit our ability to identify which linguistic patterns represent robust discourses (Ryan, Wray, and Stubbs Citation1997). We overcome this concern by combining the discourse analysis with textual analysis using R. With this empirical, linguistic analysis and description method, we start with the corpus (text) as the primary data point. Such a methodological synthesis between a textual analysis based on software and discourse analysis enables us to examine more text and make more accurate generalizations about language uses in the analysed texts. It also informs the interpretive phase of our research, by producing patterns derived from the descriptive data that mitigate the potential bias in subjective data interpretations (Ryan, Wray, and Stubbs Citation1997; Orpin Citation2005). That is, our method explicitly comprises two phases: descriptive and interpretive. In the descriptive phase, we identify keywords and keyword combinations and their frequencies. In the interpretive phase, we analyse and interpret our data.

Data selection

We conduct our assessments in The Netherlands and Kosovo, two European countries that accommodate entrepreneurship in distinct ways. By acknowledging the potential for dramatic differences in entrepreneurship across contexts (Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017), we view entrepreneurship as a social construct that has varying meanings, particularly for transitioning versus advanced economies (Smallbone and Welter Citation2003), and we seek to identify discursive nuances or divergences between these two relevant contexts (Mason, Moran, and Carey Citation2019). Then we can establish how different forms and understandings emerge in different contexts for entrepreneurship, as well as the role of context in defining the relationship among discourse, ideology, entrepreneurship, and policymaking. Furthermore, our comparative research approach acknowledges what is included, or not, in each entrepreneurship discourse promulgated by each country (Ahl and Nelson Citation2014).

The data selection process began with an effort to identify relevant institutions responsible for entrepreneurship policymaking. We focused on governmental institutions that produce political agendas focused on entrepreneurship. By assessing political agendas, rather than policies, we gain a more action-oriented corpus that accurately reflects the countries’ actual perspectives on entrepreneurship. We screened a total of 200 documents for relevance, and to avoid selection bias or distortion, we set clear criteria: First, the documents had to be available in English, as well as the country’s native language. Because we analyze agendas from countries with different languages, we need to compare only those agendas published in the same language, to minimize the risk of deviating from the context in the translation process. Second, the sources of the documents had to be institutions with consistent histories of promoting entrepreneurship, which should have a more decisive role in constructing entrepreneurship than institutions that infrequently include entrepreneurship in their agendas. We selected 20 political agendas (10 from each country) for analysis, published between 2013 and 2020, each document was assigned a code (see ) that we use in our subsequent discussion to identify the sources of sample quotes.

Table 1. Documents from The Netherlands.

Table 2. Documents from Kosovo.

In total, we reviewed 393 pages of text for The Netherlands and 744 pages of text for Kosovo. This discrepancy in the number of pages per document appears to be due to the inclusion of more tables and figures in policy texts in Kosovo. The former texts were produced by The Netherlands Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, whose explicit aim is to promote The Netherlands as a country of enterprise. It is committed to creating an entrepreneurial business climate by giving entrepreneurs room to innovate and grow. In Kosovo, we collected texts published by the Office of the Prime Minister, Ministry of Economic Development (which includes the Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Innovation), and the Ministry of Trade and Industry. These ministries share a common objective of supporting Kosovo’s private sector by establishing policies to improve its business climate.

In the case of Kosovo, national strategies are drafted by ruling governments and go through a public consultation process that allows the participation of interested parties and the public who can provide feedback before strategies are ratified in the parliament of Kosovo. After the public consultations, subject to relevant iterations, laws or policies are voted and ratified in the Parliament. In The Netherlands, a bill needs to be passed by the Parliament and signed by the monarch, then countersigned by the relevant minister, before entering into law. Such acts of Parliament also needs to be signed by the King before they can become law. See for our methodological appproach.

Table 3. Methodological approach.

Data analysis

Data examination using software

To start, we assess the text by applying R software to identify keywords and keyword combinations related to entrepreneurship. Then we examined our data with R, such that we can explore a large set of documents and establish a more accurate interpretation of our data by minimizing interpretive or selection biases. Before submitting the texts we gathered from governmental institutions to our database, we preprocessed the data, by cleaning the text (e.g. removing irrelevant words), performing tokenization (breaking text documents into words or full sentences), and extracting features (e.g. key themes and categories). The resulting database of 260,766 words represents processed data for our research. After indexing the data (assigning specific terms or numbers), to structure the text and support more unrestricted access to it, we began the mining and analysis processes.

The data exploration techniques aim to generate new knowledge, such as identifying keywords, keyword combinations, and their frequencies. Such output provides a strong foundation for the interpretive phase of our data analysis, for which we adopt the data coding approach suggested by Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton (Citation2013). In identifying keywords and keyword combinations, we can code all the data in our large data set, which otherwise would be too cumbersome. For example, with the identified keyword government, we search effectively for phrases within the data set that include this term and thereby identify relevant codes, themes, and discourses.

Discourse analysis

In the next phase of data analysis, we conducted a discourse analysis (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013). The coding process relied on statistical output from the descriptive phase, which adds rigour and transparency to our data analysis and also enables us to identify and contextualize important codes. First, with computer-aided open coding (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998), we generate first-order concepts. By assessing keywords such as economy, we can localize codes such as ‘The economy of Kosovo will develop through the private sector as the most effective ways to generate value and allocate resources in the economy’ or ‘We prioritize and focus efforts on the sectors, markets, and technologies that are most promising and add the highest economic and societal value for The Netherlands’.

Second, we analysed and compared common first-order concepts, grouping them into larger second-order themes, such as competitiveness through entrepreneurship, supportive government schemes for entrepreneurship, or supportive legislation for entrepreneurship. Thus we reduce the set of codes to a more manageable size (Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013) and identify broader themes related to entrepreneurship that also hint at aggregate dimensions.

Third, from the list of second-order themes, we identified common aggregatedimensions that we can classify as dominant discourses related to entrepreneurship. For example, from the second-order themes employability through entrepreneurship and competitiveness through entrepreneurship,we derived an aggregate dimension related to the discourse of (economic) power. Moreover, in this phase, we analyzed variations in the characteristics of the aggregate dimensions (Strauss and Corbin Citation1998) to specify dominant discourses related to entrepreneurship (see )

Table 4. Data structure.

Findings

In presenting the results of the descriptive phase, we elaborate on the initial part of our data analysis, introducing keywords and keyword combinations and their respective frequencies. Then we present the results of the interpretive phase and elaborate on the themes and discourses thus revealed. Finally, we use illustrative data to present the dominant discourses we find.

Descriptive phase

Keywords & keyword combinations, The Netherlands

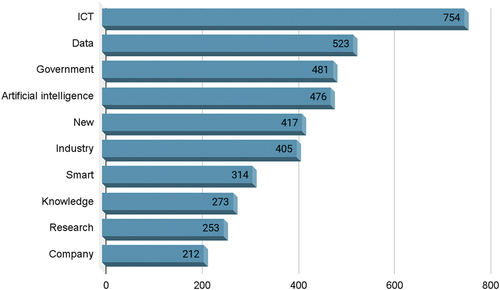

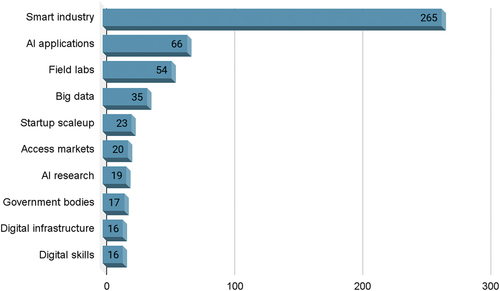

Our analysis reveals that policy texts in The Netherlands include a broad range of words referring to entrepreneurship, but the most used keywords () signal a strong emphasis on technology, with frequent terms such as ICT (754 times), data (523 times), and artificial intelligence (476 times). Furthermore, the identified keyword combinations suggest the context in which the keywords in tend to be used; as we list in , these frequent keyword combinations include smart industry, AI applications, field labs, big data, and startup scale. Note that though we identify a wider range of keyword combinations, we focus only on combinations relevant to entrepreneurship. These frequent keywords and keyword combinations help us identify and subsequently elaborate discourses attached to entrepreneurship in The Netherlands.

Keywords & keyword combinations, Kosovo

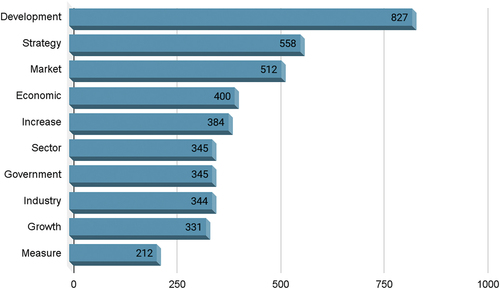

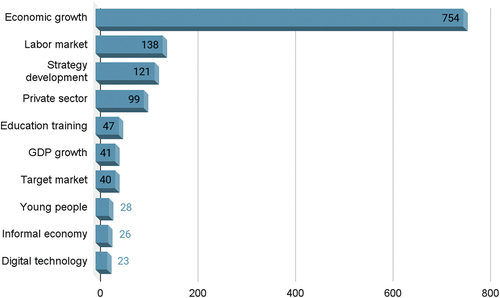

In Kosovo, the main keywords used to refer to entrepreneurship include development, strategy, market, economic, and increase (), and the most used, relevant keyword combinations refer to economic growth (development), labour market, strategy development, private sector, and education training (). Here again, we identify a broader range of keyword combinations in the text but exclude those that are irrelevant to entrepreneurship. Furthermore, some keyword combinations are similar enough to be merged.

Interpretive phase

In this phase, we outline and challenge dominant discourses identified in both policy discourses, then elaborate on the discursive nuances between the settings to specify how contextual factors influence the hegemonic workings of discourses. Through this critical examination and interpretation of dominant discourses, we uncover and interpret implicit and explicit meanings attached to entrepreneurship, supported by evidence. The combination of software-enabled textual analysis and discourse analysis uncovers some hidden meanings attached to entrepreneurship that likely would have remained unnoticed without such a comprehensive empirical scrutiny.

In particular, we identify three dominant discourses invoked by the political agendas: the discourse of (economic) power, the discourse of the protectorate, and the discourse of enterprise. These discourses are more dominant and rigid in Kosovo, a transitioning economy, than in The Netherlands, a more economically and socially developed context. In the latter, the dominant discourses appear less hegemonic than in the former; for example, they do not constrain entrepreneurial agency by attributing achievements mainly to backing from the government, and they reveal a broader view of entrepreneurship that includes various issues, such as environmental protection. This point is not to suggest that the three dominant discourses do not overwhelm entrepreneurship discourse in The Netherlands; our data reveal clear associations of entrepreneurship and economic growth, entrepreneurship and governmental intervention, and entrepreneurship and enterprise in The Netherlands. However, in relative terms, we find that these prevailing discourses are more often accompanied by themes that serve to diversify the discourse in The Netherlands, such as concerns about environmental protection, product safety issues, or research. In contrast, the entrepreneurship discourse in Kosovo appears more strictly bound to the dominant rationale, as we elaborate next with illustrative data.

Discourse of (economic) power

Both sets of political agendas link entrepreneurship to economic growth (employability and competitiveness) and innovation, reflecting what we call the discourse of (economic) power. It comprises the themes of employability through entrepreneurship and competitiveness through entrepreneurship, suggesting a primary link to job creation, competitiveness, and productivity. For example, a description of National Development Strategy for 2016–2017, published by the office of the Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, stated:

The Kosovo Government Programme has set forth the establishment of the Development and Employment Fund to support the private sector to serve as the main mechanism for economic growth and job creation

This phrasing emphasizes a dominant entrepreneurship association in Kosovo, namely, the ability to produce economic growth through the private sector. In contrast, our data suggest a closer link between entrepreneurship and economic growth in The Netherlands. For example, in documentation of the Smart Industry Implementation Agenda for 2018–2021, an excerpt states:

To safeguard jobs and economic growth, we face the important challenge of digitizing our industry and thereby ensuring it is fit for the future (10)

That is, efforts to support entrepreneurship by digitizing entire industries reflect an economic rationale, based on protecting jobs and economic growth.

Although our data indicate that entrepreneurship is closely related to economic progression in both contexts, we find a more prevalent dominance of an economic rationale in Kosovo. That is, in Kosovo, entrepreneurship is predominantly framed as an economic concept, whereas the policy discourse in The Netherlands acknowledges its complexity by integrating social and environmental considerations. A document published by the Ministry of Economic Affairs through Smart Industry cites the empowerment of Dutch leaders for example, promising that the government aims to ‘prioritize and focus efforts on the sectors, markets, and technologies that are most promising and add the highest economic and societal value for The Netherlands’ (08). Such entrepreneurial and social considerations are intertwined, rather than the latter assuming a secondary role. The Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy also describes Ambitious Entrepreneurship in Practice by elaborating benefits of entrepreneurship pertaining to ‘increased safety of employees and product users and the positive impact on the environment’ (01).

Furthermore, in Kosovo, entrepreneurship is strongly competitive in its orientation, such that a dominant grand narrative describes entrepreneurs as ‘heroic’ individuals who keep the economy running by creating jobs and enhancing national competitiveness. Our data reveal more than 400 mentions of the keyword economic and 198 keyword combinations featuring economic growth. National Development Strategy documents accordingly detail the importance of entrepreneurship for economic progression, describing how the ‘economy of Kosovo will develop through the private sector as the most effective ways to generate value and allocate resources in the economy’ (15) and citing, as a critical governmental objective, the ‘development of private sector competitiveness through industrial development and improvement the business environment’ (18). Other considerations, beyond economic progress (e.g. how entrepreneurship might address social needs) mainly appear as epiphenomena in Kosovo’s entrepreneurship discourse or simply do not appear in the policy texts. In The Netherlands, entrepreneurship is portrayed as a multifaceted concept, linked to social, environmental, and economic outcomes. The societal considerations also are not limited to mature ventures but rather appear explicitly cultivated for all venture stages. The policy texts refer to devoted efforts to educate early-stage startups about being socially responsible and producing environmentally friendly products, as in the following document:

The goal is to enable each early-stage startup with the potential to deliver large societal and climate impact in The Netherlands to access appropriate funding to develop the idea or technology into a commercially scalable venture (08).

In contrast, even agendas that explicitly target early-stage ventures in Kosovo seem to cultivate and sustain economic rationalism exclusively.

Problematizing the discourse of (economic) power

Especially in a transitioning economy such as Kosovo, it seems counterproductive to instal hegemonic discourses of economic power, because such discourses suggest a discriminatory perspective. That is, entrepreneurship is still gaining relevance and remains in a relatively early stage, but this policy discourse could promote an ideologically driven view and dominant discourses that will be difficult to challenge in the future, such that it may limit other approaches to entrepreneurship, including those that prioritize social issues. Policy agendas that target early-stage enterprises in Kosovo may be teaching them a single-minded focus on economic power that, as Welter et al. (Citation2016, 312) phrase it, can systematically close off a beneficial ‘multiplicity of perspectives’. In turn, scholars cannot develop clear theory, and policymakers cannot establish policies that will lead to more extensive and varied forms of value. Even though we find clear evidence of the discourse of (economic) power in The Netherlands too, the policy texts in that country also introduce young entrepreneurs to a broader conceptualization that can increase their awareness of perspectives beyond wealth creation or economic progression.

Discourse of the protectorate

In political discourses, the term ‘protectorates’ refers to territories that have been granted some autonomy and independence, though they remain subject to the ruling state; we use it to draw parallels between entrepreneurs and local governments. We find that the political agendas of both countries inflict the discourse of the protectorate on entrepreneurship discourse, by representing the government as a crucial agent. For example, the lists of keywords show that government is frequent in both, with 481 occurrences in Dutch documents and 345 in Kosovan documents. It reflects two main themes, namely, supportive legislation for entrepreneurship and supportive government schemes for entrepreneurship. We identify a rhetoric, in both policy discourses, that portrays entrepreneurs as ‘puppets’ of the economy, who are vital for creating jobs and enhancing competitiveness, but who act in accordance with governmental structures. In this view, entrepreneurs are not heroic figures, responsible for economic and social development, but rather are dependents of the government. In line with the general definition of a protectorate, entrepreneurs have some degree of freedom to operate, but they are portrayed as always dependent on the ‘greater’ power of the government. Consider excerpts of policy texts from both countries:

The government will create economic policies that will guide and support enterprises to combine knowledge, capacities, skills, and resources (17)

The Dutch government wants to give entrepreneurs more freedom to run their businesses and make optimum use of ICT … by easing the regulatory burden, establishing future-proof rules and removing barriers within the single market (04)

Both policy discourses explicitly claim a role for government in supporting and promoting entrepreneurship, as well as responsibility for critical processes related to the mobilization of resources, enhancement of required skills, or easing of regulatory burdens. In turn, it seems as if entrepreneurs do not control all the resources they need to succeed in their initiatives, which ‘removes the possibility of entrepreneurs creating personal agency through the discourse of their importance to society’ (Perren and Jennings Citation2005, 179).

Although our comparative approach confirms that both sets of texts explicitly elaborate on how necessary governmental support is for venture creation and growth, we also note that whereas entrepreneurs in Kosovo are portrayed as highly dependent, Dutch entrepreneurs receive relatively more credit for creating sustainable products and engaging in research to foster entrepreneurship. To illustrate, a statement in a document about Ambitious Entrepreneurship in Practice explicitly identifies collaborations between entrepreneurs and researchers as a source of knowledge creation:

Thanks to research, ISA [a Dutch company that previously profited from governmental support] has now built up a portfolio with two clinical phases of therapeutic SLP vaccines for various forms of cancer and precancerous stages (01).

This same document also acknowledges both corporate and university research partners, pointing to the idea of ‘rapid charging of lithium-ion batteries that a group of students in Delft researched and how later a business emerged’ (01). In our descriptive data, we note that the keyword research ranks among the most prominent words in the Dutch documents (frequency = 253). In Kosovo, we do not find any explicit credit assigned to other contributors, beyond the government. A critical difference is that whereas the governmental authors implicitly position themselves as central figures in entrepreneurial initiatives in Kosovo, they claim less influence in The Netherlands, so the resulting policy texts imply less dependence on governmental institutions.

We offer a potential explanation, based on the sense that entrepreneurs in The Netherlands may appear more mature, such that they just need a little push to grow their ventures. In contrast, even in established firms in Kosovo, entrepreneurs are portrayed as nascent and in need of assistance with financing, legislation, training, and education. Such suppositions are supported our consideration of the programs initiated in Kosovo to support the private sector. Since the Ministry of Innovation and Entrepreneurship was established in 2017, its strategy has been to support enterprises in Kosovo. Although its mission statement cites start-ups, its financial support is available to established enterprises that the Ministry considers as in need of further assistance to grow; its policy texts implicitly hint that all enterprises in Kosovo need such backing, in stating for example that it seeks the ‘Development of entrepreneurship through training/consulting programs’ and promises that the ‘government will work towards creating the necessary skills to compete in the private sector’ (17). This implied nascence seemingly legitimizes the government’s intervention and sustains the discourse of the protectorate in Kosovo.

Problematizing the discourse of the protectorate

This particular discourse seems counterproductive and counterintuitive to the goal of establishing free enterprise and moving away from a centralized economy. It deprives entrepreneurs of personal agency, such that they become implicitly subsumed into the economic machinery (Perren and Jennings Citation2005). In a sense, the discourse of the protectorate subjects entrepreneurs to further oppression and control by policies that instead claim to support their quests for liberation, autonomy, and progression. Such implied dependence on the government also may leave entrepreneurs exposed to corruption and could produce a system that favours a particular group of entrepreneurs, with an unfair distribution of public or supportive resources. Especially in an emerging economy such as Kosovo, which is characterized by institutional and legislative voids, the resulting system might constrain entrepreneurial agency by unfairly protecting certain entrepreneurial initiatives over others that are more meritorious and promising.

Discourse of enterprise

Finally, the discourse of enterprise is specific to the enterprise level. Our data reveal that most of the policy texts interpret entrepreneurship only at this level and imply it is limited to venture creation and venture performance, such that entrepreneurs, through their ventures, enact employability and competitiveness. Two major themes underlie this discourse: economic growth through enterprises and supportive scheme for enterprises. The supportive schemes are limited to enterprises, which are portrayed as vital to economic growth. Similarly, the descriptive data indicate that the keyword company was used 212 times to refer to entrepreneurial initiatives in Dutch policy discourse. But statements from both governments reflect this view:

Start-ups and scaleups are important innovators within the economy. They create a new activity and challenge the established order to modernize. (04)

The governmental fund will enable the focus on startups, support existing businesses, and promote new investments. (17)

We also note that this enterprise discourse is especially prevalent in documents that highlight schemes to support entrepreneurship by enhancing conditions in the private sector, primarily through financial incentives. For example, the

Kosovo Government Programme 2015–2018 has set forth the establishment of the Development and Employment Fund, whose purpose is to support the private sector to serve as the main mechanism for economic growth and job creation (15).

The ICT fund, distributed in 2018 by the Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Innovation in Kosovo, also is explicitly targeted, such that it ‘will focus on startups, support existing businesses, and promote new investments’ (17). Shared efforts by governmental institutions, the private sector, and research institutions to foster startups and scale-ups also are evident in an excerpt from the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy:

Working with the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Economic affairs Climate, RVO and others, we will design and align international expansion instruments to optimally serve startup and scaleup entrepreneurs in their growth and access to markets strategy. (08)

Unlike the comparative findings for the discourses of (economic) power and of the protectorate, we find no substantial discursive nuances between The Netherlands and Kosovo with regard to the discourse of enterprise. Instead, policy texts from both settings limit perspectives on entrepreneurship to the enterprise level.

Problematizing the discourse of enterprise

This discourse, by defining entrepreneurship as enterprise, may constrain other forms of entrepreneurship, including in the public sector or by non-profit organizations (Berglund and Wigren Citation2012; Anderson Citation2015). As Calás, Smircich, and Bourne (Citation2009) predict, entrepreneurship brings about new firms, products, and services but also new openings for more liberating forms of individual and collective existence. Because entrepreneurship policy is decisive for defining entrepreneurship in a particular setting, a prevailing discourse of enterprise provides a limited view of entrepreneurship to the public, which may hinder aspiring entrepreneurs from pursuing other forms. For example, the dominant focus on how enterprises perform, such as in terms of job creation, may discourage entrepreneurial initiatives that aspire to tackle social issues. Moreover, beyond activities by enterprises and individuals, entrepreneurship also is a process of value creation that changes society, for better or worse (Steyaert and Katz Citation2004; Hjorth and Holt Citation2016). As Hjorth and Holt (Citation2016) argue, equating entrepreneurship with just enterprise inaccurately prioritizes an individualistic relationship with value creation, rather than allowing for the various entrepreneurial outcomes that can arise in reality. A broader conceptualization supports the emergence of multiple forms of social creativity, offering more possibilities for new value creation (Hjorth and Holt Citation2016). (see )

Table 5. Illustrative quotes of dominant discourses.

Discussion

In accepting that entrepreneurship is socially embedded and influenced by societal discourses (e.g. Anderson and Smith Citation2007; Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017; Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021), we purposefully combine content analysis (text mining) and discourse analysis to analyse entrepreneurship policy texts in The Netherlands and Kosovo and thereby disclose the distinct discursive threads they portray and produce. In revealing these discursive nuances, we elaborate on the different constructions of entrepreneurship, then discern and challenge three discursive threads: discourses of (economic) power, of the protectorate, and of enterprise.

Previous studies that consider entrepreneurship discourses do not include assessments of the discursive threads in entrepreneurship policy texts (cf. Mason, Moran, and Carey Citation2019), despite the potentially powerful influences of the language used in such texts for shaping societal understanding of entrepreneurship (Anderson and Smith Citation2007). The way entrepreneurship develops depends on both the language used to describe the phenomenon and the social context (including stage of economic transformation, Smallbone and Welter Citation2001), and policy texts that help establish these features thus set clear boundaries on how people think about and behave towards entrepreneurship (Gartner Citation1993). Because the meaning is context-specific, entrepreneurship likely gets defined differently in different contexts (e.g. Smallbone and Welter Citation2003; Perren and Jennings Citation2005; Dodd, Jack, and Anderson Citation2013). Yet previous studies mostly identify common discursive threads across distinct contexts (e.g. Perren and Jennings Citation2005). Therefore, to gain a clearer view, we explicitly seek differences in entrepreneurship discourses, as signified by policymaking and the contextual understanding of entrepreneurship. Our comparative approach to analysing discursive threads in entrepreneurship policy texts reveals significant, discursive nuances that arise across different contexts, to accommodate distinct views of entrepreneurship (Anderson and Ronteau Citation2017).

Our findings in turn are theoretically relevant for both critical entrepreneurship studies (e.g. Dey, Steyaert, and Teasdale Citation2012; Da Costa and Saraiva Citation2012; Verduijn and Essers Citation2013; Hjorth and Holt Citation2016; Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021) and studies of entrepreneurship policy and contexts (e.g. Smallbone and Welter Citation2003; Perren and Jennings Citation2005), in that we offer nuanced insights into the relations among discourses, ideology, and entrepreneurship, as well as context. In particular, for research into entrepreneurship policies and contexts, we reveal significant differences in meanings ascribed to entrepreneurship, according to the discursive nuances in policy texts published in The Netherlands versus Kosovo. These discursive threads of entrepreneurship appear more rigid in Kosovo, a transitioning economy characterized by a relative unstable external environment and moderate economic and social welfare (Smallbone and Welter Citation2001). In The Netherlands, a more advanced economy, the discursive threads seem less rigid, do not dominantly constrain entrepreneurial agency, and reflect a broader view of the phenomenon.

Our findings also emphasize the relevance of context-specific societal influences in establishing a potentially limiting view of entrepreneurship’s role in society (e.g. Dodd, Jack, and Anderson Citation2013). In Kosovo, entrepreneurship is constructed as strictly limited to economic growth, whereas in The Netherlands, the discourse of economic growth persists, but it is complemented by considerations related to social change. The policy texts in The Netherlands specifically acknowledge the complexity of entrepreneurship by linking the phenomenon to social or environmental issues and promising its ability to ‘Deliver large societal and climate impact in The Netherlands’. Similarly, the discourse of the protectorate presents entrepreneurship as a phenomenon attributed to governmental backing and is more prominent in the transitioning economy, where the policy discourse explicitly describes entrepreneurial achievement as a result of governmental intervention. In the developed context, the role of government is less prominently described and also is accompanied by acknowledgements of other impacts on entrepreneurship, such as academic research. Finally, policy texts support a discourse that equates entrepreneurship with enterprise, which did not reveal any substantial discursive nuances between the two contexts.

These discursive threads have several implications, particularly in social contexts that entail early-stage economic transformations to an open market system (Smallbone and Welter Citation2001). Noting Smallbone and Welter’s (Citation2001), Smallbone and Welter (Citation2006) observation that social contexts inherited from former socialist governments strongly affect attitudes and behaviours towards society, we posit that these discursive threads might be particularly problematic in Kosovo, which requires good solutions to improve social and economic welfare, but where policy texts may be constructing pervasive, persuasive, economically focused entrepreneurship narratives. Phrasings that describe entrepreneurship as the ‘main mechanism for economic growth and job creation’ indicate that entrepreneurship is a guaranteed solution to economic development, which may create optimistic attitudes and augment its popularity. But such preferential views also represent constraints that restrict people’s thinking and acting, by influencing the way they think about entrepreneurship (Dey and Mason Citation2018). That is, these discursive threads may prevent imaginative approaches to entrepreneurship that extend beyond a dominant narrative, closing off other perspectives and alternative enactments.

Language has a critical role in establishing such boundaries (Gartner Citation1993), and we particularly question the discourse of economic power, which constructs entrepreneurship as a commercial practice without accounting for other relevant aspects, such as social issues, especially in transitional economies struggling with severe societal challenges. The other discursive threads also can be problematic; the discourse of the protectorate may deprive entrepreneurs of the means to create personal agency, once they get implicitly subsumed into the economic machinery (Perren and Jennings Citation2005). Reducing entrepreneurship to enterprises, as suggested by the discourse of enterprise, also may tend to exclude other forms of entrepreneurship, such as in the public sector, by larger corporations, or involving non-profit organizations, leading to insufficient support for these efforts (Berglund and Wigren Citation2012). It also emphasizes a capitalist relationship with value creation, preventing other potential entrepreneurial outcomes (Hjorth and Holt Citation2016).

These findings suggest some pertinent practical implications for policymakers. Our study highlights that policy texts can shape, positively or negatively, the portrayal and deployment of entrepreneurship on a regional level. Therefore, policymakers must recognize and appreciate the power of their words, in a way that involves reflecting on their likely implications as they write. Policymakers in transitioning economies may possess a relatively underdeveloped understanding of entrepreneurship. Moreover, policymakers could possess limited practical entrepreneurial experience that would help them grasp the reality and entirety of the entrepreneurial context. The policy texts they write could fall into the trap of nurturing a narrow understanding based on a limited description of the phenomenon. We caution that policymakers should consider their position as each of their interventions may further help nurture dominant discourses, positioning ‘entrepreneurs to a rhetorical loop of perpetual domination’ (Perren and Jennings Citation2005, 179). Dodd, Jack, and Anderson (Citation2013) offer evidence that, in countries where entrepreneurship is held in high regard, the attractiveness of becoming an entrepreneur is correspondingly high. To ensure such appeals, policymakers must take responsibility for the powerful impacts of their words and ensure that their policy texts portray entrepreneurship in a way that embraces the wide range of characteristics that constitute this important phenomenon. This should include an array of topics related to entrepreneurship including economic development or social welfare, as well as inform about both positive and negative aspects of the phenomenon such that aspiring entrepreneurs’ understanding of entrepreneurship is nurtured through discourses that are free of unchallenged and ideological assumptions.

We also note some limitations of our study, in terms of representativeness and generalizability. Although we include various policy documents from two contexts, a larger corpus of documents might offer more solid empirical findings and minimize the risk of distortion. We cannot conclude with high certainty that the results apply to all policy documents produced by The Netherlands and Kosovo either. More documents from different sources could establish more comprehensive results. Moreover, continued research might analyse other text sources, including laws, media, or archival data. Finally, as we repeatedly argue in this study that entrepreneurship is highly socially constructed, thus contextual and situational, we also acknowledge that our findings could be different for a different pair of transitioning/developed economies.

Conclusion

With this comprehensive, comparative review of entrepreneurship policy produced in two different contexts, we seek to move beyond studies that suggest novel perspectives on entrepreneurship (Hjorth Citation2013), by using critical scholarship to contribute to this research stream (Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021; Tedmanson et al. Citation2012). If they primarily establish economic narratives of entrepreneurship, policymakers might be at risk of creating policies that ignore its complexity and exclude alternative views. Resisting discursive threads requires challenging dominant assumptions (Verduijn and Essers Citation2013; Dodd, Anderson, and Jack Citation2021) that produce unrealistic, limited understandings of entrepreneurship. It demands acknowledging what entrepreneurship has to offer, beyond economic dimensions and enterprises, to enable path explorations of the diverse outcomes that entrepreneurship can produce, such as individual transformation (Tobias, Mair, and Barbosa-Leiker Citation2013) or emancipation (Rindova, Barry, and Ketchen Citation2009).

We hope continued research addresses such topics, using the critically discursive approach that we outline, because it is relevant for uncovering and critiquing discourses that manifest in a seemingly innate link between entrepreneurship and an economic logic. Critical discourse studies based on textual analyses can clarify the narratives produced and reflected in entrepreneurship policy texts; they do not reveal the actual intentions or motivations of the text authors, who might seek to shape and disseminate specific entrepreneurial narratives. Research that incorporates qualitative methods might uncover these underlying motives of policymakers and thus offer further insights into the link between policymaking and entrepreneurship discourses. Furthermore, cultural dimensions might be related to specific entrepreneurship discourses. We distinguish two contexts, based on economic well-being; continued research could address other cultural characteristics that distinguish different contexts to develop a more contextual, culturally oriented understanding of entrepreneurship policy discourses. Relevant cultural characteristics might include broad societal beliefs and norms that strongly inform how members of the society perceive of and engage in entrepreneurship. In line, future research could also consider regional discursive differences within countries, with a notable observation that entrepreneurship activity and prosperity may vary across regions for several reasons, including economic (Baumol Citation1990) and institutional reasons (Harbi and Anderson Citation2010). This could produce nuances in the perception of entrepreneurship and its surrounding discourses. Future research could study those differences within a single country with a specific focus on urban vis-a-vis rural areas. Finally, we call for research that analyzes policy agendas published over a more extended period, to identify trends, patterns, co-occurrences of elements, and groupings of features related to entrepreneurship.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achtenhagen, L., and F. Welter. 2011. “Surfing on the Ironing Board’ – the Representation of Women’s Entrepreneurship in German Newspapers.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (9–10): 763–786. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.520338.

- Ahl, H., and T. Nelson. 2014. “How Policy Positions Women Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis of State Discourse in Sweden and the United States.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (2): 273–291. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.08.002.

- Anderson, A. R. 2015. “Conceptualising Entrepreneurship as Economic ‘Explanation’ and the Consequent Loss of ‘Understanding’.” International Journal of Business and Globalisation 14 (2): 145. doi:10.1504/IJBG.2015.067432.

- Anderson, A. R., and S. Ronteau. 2017. “Towards an Entrepreneurial Theory of Practice; Emerging Ideas for Emerging Economies.” Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies 9 (2): 110–120. doi:10.1108/JEEE-12-2016-0054.

- Anderson, A. R., and R. Smith. 2007. “The Moral Space in Entrepreneurship: An Exploration of Ethical Imperatives and the Moral Legitimacy of Being Enterprising.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 19 (6): 479–497. doi:10.1080/08985620701672377.

- Anderson, A. R., and L. Warren. 2011. “The Entrepreneur as Hero and Jester: Enacting the Entrepreneurial Discourse.” International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship 29 (6): 589–609. doi:10.1177/0266242611416417.

- Audretsch, D. B., M. C. Keilbach, and E. E. Lehmann. 2006. “Entrepreneurship and Economic.” Growth. doi:http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195183511.001.0001.

- Baumol, W. J. 1990. “Entrepreneurship: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive.” The Journal of Political Economy 98 (5): 893–921. doi:10.1086/261712.

- Berglund, K., and C. Wigren. 2012. “Soci(et)al Entrepreneurship: The Shaping of a Different Story of Entrepreneurship.” Journal for Critical Organization Inquiry 10 (1): 9–22.

- Calás, M. B., L. Smircich, and K. A. Bourne. 2009. “Extending the Boundaries: Reframing “Entrepreneurship as Social Change” Through Feminist Perspectives.” Academy of Management Review 34 (3): 552–569. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.40633597.

- Caldas-Coulthard, C. R. 1993. “From Discourse Analysis to Critical Discourse Analysis: The Differential Representation of Women and Men Speaking in Written News.” Techniques of Description: Spoken and Written Discourse 5 (2): 196–208.

- Da Costa, A., and L. A. S. Saraiva. 2012. “Hegemonic Discourses on Entrepreneurship as an Ideological Mechanism for the Reproduction of Capital.” Organization 19 (5): 587–614. doi:10.1177/1350508412448696.

- Dey, P., and C. Mason. 2018. “Overcoming Constraints of Collective Imagination: An Inquiry into Activist Entrepreneuring, Disruptive Truth-Telling and the Creation of ‘Possible Worlds.” Journal of Business Venturing 33 (1): 84–99. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.11.002.

- Dey, P., C. Steyaert, and S. Teasdale. 2012. “Social Entrepreneurship: Critique and the Radical Enactment of the Social.” Social Enterprise Journal 8 (2): 90–107. doi:10.1108/17508611211252828.

- Dodd, S. D., A. R. Anderson, and S. Jack. 2021. ““Let Them Not Make Me a Stone”—repositioning Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Small Business Management 1–29. doi:10.1080/00472778.2020.1867734.

- Dodd, S. D., S. Jack, and A. R. Anderson. 2013. “From Admiration to Abhorrence: The Contentious Appeal of Entrepreneurship Across Europe.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (1–2): 69–89. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.746878.

- Gartner, W. B. 1993. “Words Lead to Deeds: Towards an Organizational Emergence Vocabulary.” Journal of Business Venturing 8 (3): 231–239. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(93)90029-5.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Goss, D., R. Jones, M. Betta, and J. Latham. 2011. “Power as Practice: A Micro-Sociological Analysis of the Dynamics of Emancipatory Entrepreneurship.” Organization studies 32 (2): 211–229. doi:10.1177/0170840610397471.

- Harbi, S. E., and A. R. Anderson. 2010. “Institutions and the Shaping of Different Forms of Entrepreneurship.” The Journal of Socio-Economics 39 (3): 436–444. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2010.02.011.

- Hardy, C., B. Harley, and N. Phillips. 2004. “Discourse Analysis and Content Analysis: Two Solitudes.” Qualitative Methods 2 (1): 19–22.

- Hjorth, D. 2013. “Public Entrepreneurship: Desiring Social Change, Creating Sociality.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (1–2): 34–51. doi:10.1080/08985626.2012.746883.

- Hjorth, D., and R. Holt. 2016. “Its Entrepreneurship, Not Enterprise: Ai Weiwei as Entrepreneur.” Journal of Business Venturing Insights 5: 50–54. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2016.03.001.

- Hopf, T. 2004. “Discourse and Content Analysis: Some Fundamental Incompatibilities.” Qualitative Methods 2 (1): 31–33.

- Jennings, J. E., P. D. Jennings, and M. Sharifian. 2016. “Living the Dream? Assessing the “Entrepreneurship as Emancipation” Perspective in a Developed Region.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 40 (1): 81–110. doi:10.1111/etap.12106.

- Jones, C., and A. Spicer. 2009. “Unmasking the Entrepreneur.” doi:http://doi.org/10.4337/9781781952689.

- Lippmann, S., A. Davis, and H. E. Aldrich. 2005. “Entrepreneurship and Inequality.” Entrepreneurship Research in the Sociology of Work 15: 3–31.

- Marsh, D., and P. Thomas. 2017. “The Governance of Welfare and the Expropriation of the Common.” Critical Perspectives on Entrepreneurship 1: 225–244.

- Mason, C., M. Moran, and G. Carey. 2019. “Never Mind the Buzzwords: Comparing Social Enterprise Policy-Making in the United Kingdom and Australia.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 12 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1080/19420676.2019.1668828.

- Ogbor, J. O. 2000. “Mythicizing and Reification in Entrepreneurial Discourse: Ideology-Critique of Entrepreneurial Studies.” Journal of Management Studies 37 (5): 605–635. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00196.

- Orpin, D. 2005. “Corpus Linguistics and Critical Discourse Analysis: Examining the Ideology of Sleaze.” International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 10 (1): 37–61. doi:10.1075/ijcl.10.1.03orp.

- Perren, L., and P. L. Jennings. 2005. “Government Discourses on Entrepreneurship: Issues of Legitimization, Subjugation, and Power.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 29 (2): 173–184. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00075.x.

- Perren, L., and J. Sapsed. 2013. “Innovation as Politics: The Rise and Reshaping of Innovation in UK Parliamentary Discourse 1960–2005.” Research Policy 42 (10): 1815–1828. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.012.

- Pettersson, K., H. Ahl, K. Berglund, and M. Tillmar. 2017. “In the Name of Women? Feminist Readings of Policies for Women’s Entrepreneurship in Scandinavia.” Scandinavian Journal of Management 33 (1): 50–63. doi:10.1016/j.scaman.2017.01.002.

- Rehn, A. 2008. “On Meta-Ideology and Moralization: A Prolegomena to a Critique of Management Studies.” Organization 15 (4): 598–609. doi:10.1177/1350508408091009.

- Rindova, V., D. Barry, and D. J. Ketchen. 2009. “Entrepreneuring as Emancipation.” Academy of Management Review 34 (3): 477–491. doi:10.5465/amr.2009.40632647.

- Ryan, A., A. Wray, and M. Stubbs. 1997. “Whorf’s Children: Critical Comments on Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA).” British Studies in Applied Linguistics 12: 100–116.

- Smallbone, D., and F. Welter. 2001. “The Distinctiveness of Entrepreneurship in Transition Economies.” Small Business Economics 16 (4): 249–262. doi:10.1023/A:1011159216578.

- Smallbone, D., and F. Welter. 2003. Entrepreneurship in Transition Economies: Necessity or Opportunity Driven. Babson College, USA: Babson College-Kaufmann Foundation.

- Smallbone, D., and F. Welter. 2006. “Conceptualising Entrepreneurship in a Transition Context.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 3 (2): 190–206. doi:10.1504/IJESB.2006.008928.

- Steyaert, C., and J. Katz. 2004. “Reclaiming the Space of Entrepreneurship in Society: Geographical, Discursive and Social Dimensions.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 16 (3): 179–196. doi:10.1080/0898562042000197135.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Stubbs, M. 1992. “Institutional Linguistics: Language and Institutions, Linguistics, and Sociology.” Thirty Years of Linguistic Evolution 189: 189–214.

- Stubbs, M., and A. Gerbig. 1993. “Human and Inhuman Geography: On the Computer-Assisted Analysis of Long Texts.” Data, description, discourse ed: 64–85.

- Tedmanson, D., K. Verduijn, C. Essers, and W. Gartner. 2012. “Critical Perspectives in Entrepreneurship Research.” Organization 19 (5): 531–541. 9781138938878. doi:10.1177/1350508412458495.

- Tobias, J. M., J. Mair, and C. Barbosa-Leiker. 2013. “Toward a Theory of Transformative Entrepreneuring: Poverty Reduction and Conflict Resolution in Rwandas Entrepreneurial Coffee Sector.” Journal of Business Venturing 28 (6): 728–742. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.03.003.

- Verduijn, K., and C. Essers. 2013. “Questioning Dominant Entrepreneurship Assumptions: The Case of Female Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurs.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 25 (7–8): 612–630. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.814718.

- Welter, F., T. Baker, D. B. Audretsch, and W. B. Gartner. 2016. “Everyday Entrepreneurship—a Call for Entrepreneurship Research to Embrace Entrepreneurial Diversity.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 41 (3): 311–321. doi:10.1111/etap.12258.

- Wiklund, J., M. Wright, and S. A. Zahra. 2019. “Conquering Relevance: Entrepreneurship Research’s Grand Challenge.” Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice 43 (3): 419–436. doi:10.1177/1042258718807478.

- Wodak, R., and B. Busch. 2004. “Approaches to Media Texts.” The SAGE Handbook of Media Studies 1: 105–122.