ABSTRACT

In this paper, we apply a feminist interpretation and an extension of Bourdieu’s theory of practice to explore the gap in our understanding between gender gap issues – the institutionalized and structural inequalities that underpin the differential access to resources by women and men – and women business owners. Drawing on an interpretivist analysis of the lived experience of women entrepreneurs who were members of women-only or open-to-all formal entrepreneurship networks, we examine their enculturation and the strategies they employ to be deemed credible players in the field. We conclude that women-only formal entrepreneurship networks have had a limited impact on helping these women overcome the isolating and individualizing effects of a gendered entrepreneurial field. Despite the promise of familiarization with and sensitization to the field, women-only formal entrepreneurship networks only serve to perpetuate and reproduce the embedded masculinity of the entrepreneurship domain in the absence of appropriate activating mechanisms or ‘margins of intervention’.

This transformative edge [to feminism] assumes that no emancipatory process, however partial, is ever completely subsumed or incorporated into the dominant socio-economic life conditions, to which it is attached by critical opposition. Margins of intervention remain available, albeit as virtual potential. The trick is how to activate them. (Braidotti Citation2022a, 3)

Introduction

How do gendered dispositions (Miller Citation2016) produce and reproduce fields of socioeconomic production, such as entrepreneurship? Such fields depend on numerous individuals behaving in predictable mutually understood ways, organized by ‘conventions’, or shared assumptions (both explicit and implicit) about the ‘way things are done’ (Miller Citation2016). They also rely on particular kinds of participants, that is, those individuals with the skills and dispositions needed to maintain the fields and their conventions (Thomson Citation2014).

For Bourdieu (Citation1984, Citation2000) these dispositions are a ‘specific habitus’, a set of internalized, embodied ways of thinking, feeling, and acting shaped by social structures. Viewing habitus as incorporated history, a generating principle, a modus operandi that produces the regular improvisations we call ‘social practice’, Bourdieu comprehends doing gender as ‘both the action of the individual and as a socially prestructured practice’ (Krais Citation2000, 57): what he refers to as the ‘gendered and gendering habitus’ (Bourdieu Citation1990b, 11). He goes on to argue that male domination functions as an everyday structure and activity: a gendered view of the world is stored in our habitus, which is ‘profoundly and inescapably shaped by a pattern of classification that constructs male and female as polar opposites’ (Krais Citation2000, 58). In other words, ‘gender is a fundamental dimension of the habitus which modifies, as do the sharp or the clef in music, all social features connected to fundamental social factors’ (Bourdieu Citation1977, 222).

In this paper, we follow a stream of feminist appropriations and extensions of Bourdieu’s work (Adkins and Skeggs Citation2004; Krais Citation2000; Moi Citation1991, Citation1999) to explain how gender affects the field-habitus relationship in the field of entrepreneurship and to further identify the gendered nature of the field mechanisms (such as capital and doxa, which are objective structures, a medium of operation reflected in features which arise from their procedures), and field conditions (such as interest/illusio and symbolic violence, which are subjective representations of how fields are present in individuals and their repercussions) (Grenfell Citation2014b).

The starting point for our analysis is that despite the representation of entrepreneurship as a field of open entry (Adamson and Kelan Citation2019; Lewis Citation2014; Sullivan and Delaney Citation2017), women remain under-represented relative to men (Greene and Brush Citation2023; Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023; OECD-GWEP Citation2021; Pfefferman, Frenkel, and Gilad Citation2022). Accordingly, there has been an expansion of policy initiatives aimed at addressing this underrepresentation and enhancing women’s position in entrepreneurship by supporting the acquisition of a particular entrepreneurial logic (Ahl and Marlow Citation2021; Arshed, Chalmers, and Matthews Citation2019; Foss et al. Citation2019; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020; Henry et al. Citation2017; Henry, Coleman, and Lewis Citation2023). Thus, it is argued, for example, that by improving women’s access to networks, capital and appropriate support structures and processes, their contribution and positions within entrepreneurship will be enhanced. However, despite these lofty aims, women’s entrepreneurship policy, in both the developed world and the Global South, is characterized by the ‘implicit ideological premises of programs [that] tend to overestimate the empowerment potential of entrepreneurship’ (Wood, Hg, and Bastian Citation2021, 2), as a manifestation of a wider gender blindness in entrepreneurship (Lewis Citation2013).

A key element in women’s entrepreneurship policies has been the establishment of formally constituted women-only entrepreneurship networks as a catalyst to the development of an entrepreneurial culture (Fritsch Citation2011). These are intended to serve as a mechanism to address issues of difference and diversity in the light of the homogeneity and discrimination against ‘others’ characteristic of competitive production systems (Ettlinger Citation2001). They also are intended to develop the social capital of women business owners and prospective entrepreneurs through psychic investments (those aspects of work which ‘get inside’ the lives of women, transforming and shaping their subjectivities and relations with others: Gill Citation2009; Scharff Citation2011; Citation2012, Citation2015 Walkerdine Citation2003) in particular kinds of work (i.e. entrepreneurship) as sites of personal satisfaction (Cockayne Citation2015).

As such, these represent ‘margins of intervention’ which define the scope for, or degrees of freedom of, policy interventions in a particular sphere (Rodrik and Sabel Citation2020; Semigallia Citation2012). These margins of intervention also, potentially, represent critical and creative ways in which the marginalized experience the actualization of a possible future. This future in turn is manifest as a ‘reservoir of yet unrealized possibilities that cannot be brought about by dialectical opposition to the present (that is, actual) conditions. They rather need to be called forth by a collective relational endeavour of co-creation of the conditions to actualize this potential’ (Braidotti Citation2021, 149). How and to what extent these interventions bring about these unrealized possibilities, however, remains a matter of continuing debate in entrepreneurship.

In terms of women’s entrepreneurship policy, and despite the early recognition of the institutionalized and structural inequalities that underpin the differential access to resources by women and men (Perrin Citation2021; Yllö Citation1984), there is a gap in our understanding, and we are still missing ‘an approach that links gender gap issues and women business owners in a coherent manner’ (Greene and Brush Citation2023, 15). We argue that the application of a feminist interpretation and extension of Bourdieu’s theory of embodied practice can provide such a link. Specifically, given the relative lack of attention directed to the experience of women in these formal entrepreneurial networks (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020; Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015; McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019), and the advocacy of a more practice-oriented approach to policy analysis (Arshed, Chalmers, and Matthews Citation2019), we formulate the following research question: How do women entrepreneurs perceive the effectiveness of formal women-only entrepreneurial networks in mitigating the isolation and individualization inherent in the gendered entrepreneurial policy landscape? In addressing this question, we draw on a gendered interpretation of Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Adkins and Skeggs Citation2004; Bourdieu Citation1977). Although there has been increasing interest in Bourdieu in entrepreneurship (see for example Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2014; Hill Citation2018; Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023; Spigel Citation2017), most of this research (including work specifically on Bourdieu and gender – Shaw et al. Citation2009; Vincent Citation2016) has been restricted to the application of his ideas on capital and capital conversion, to the relative neglect of other aspects of his ‘thinking tools’ (Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023).

We make the following contributions: First, drawing on feminist readings of Bourdieu’s theory of practice, we bring together feminist and Bourdieusian scholarship in entrepreneurship, two research perspectives hitherto, with some notable exceptions (e.g. Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023; Shaw et al. Citation2009; Vincent Citation2016; Vincent and Pagan Citation2019), addressed separately. In so doing, we extend Bourdieusian research in entrepreneurship by exploring the relationships between field, habitus, doxa, illusio and symbolic violence. Second, in illuminating how formal women-only entrepreneurial networks can perpetuate and reproduce the embedded masculinity of entrepreneurship, we develop a more comprehensive understanding of the gendered doxic order as a system of presuppositions underpinning behaviour in a field. Third, by highlighting the perceptions and lived experiences of women entrepreneurs, we draw attention to these relationships and demonstrate the ways in which capital and access to it might be gendered. Finally, with regards to policy implications we argue that to the extent to which women-only entrepreneurial networks are focused on equity rather than equality their potential as ‘margins of intervention’ will remain unexploited, and the positive implications of these will not be realized unless and until there are appropriate activating mechanisms to prevent their perpetuating and reproducing the embedded masculinity of the entrepreneurship domain.

The paper is structured as follows. In the following section, we discuss formal women-only entrepreneurship networks as an instrument of entrepreneurship policy. The next section reviews the nature of entrepreneurship as a gendered social practice, integrating recent feminist perspectives with Bourdieu’s theory of practice. We then detail our research design and data analysis protocols. On the basis of this, we summarize our findings and critically reflect on the implications for a Bourdieusian understanding of gender relations and entrepreneurial action.

Entrepreneurship policy: women-only entrepreneurial networks

Networking, as a process, can be defined as the coming together of similarly minded people for the purposes of contact, friendship, and support (Brass et al. Citation2004), and women’s business networks can be defined as ‘independent, bottom-up initiatives that organize women’s voices and experiences to address the status quo in the gendered world of work’ (Villesèche, Meliou, and Jha Citation2022, 1903). In both corporate and entrepreneurial contexts (Jack Citation2010; Klyver and Terjesen Citation2007), successful networking has been argued to positively influence career outcomes such as increased job opportunities, job performance, income, promotion and advancement and career satisfaction through the provision of access to information, enhanced visibility, social support, business leads, access to resources, collaboration opportunities, strategy-making and professional support (Singh et al. Citation2006). Critics of women’s business networks, however, argue that while at the individual level these groups do develop support strategies that meet their member’s needs, they do so at the expense of their failure to address organizational and structural inequalities (Petrucci Citation2020).

Research to date has consistently demonstrated the importance of networks (formal and informal) in generating social capital (Coleman Citation1988), providing access to knowledge, customers, suppliers and investors (Florin, Lubatkin, and Schulz Citation2003; Hoang and Antoncic Citation2003), and enhancing entrepreneurial self-efficacy and legitimacy (Arshed, Chalmers, and Matthews Citation2019). Prior research has also demonstrated the gendered nature of entrepreneurial networking and networks (Brush et al. Citation2019, Foss Citation2010; Neergaard, Shaw, and Carter Citation2005; Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody Citation2000), in that men are more instrumentally active in promoting their careers while women tend to use networks for social support (Ibarra Citation1992; McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019). As a result, the distinctive structure of women’s networks makes more difficult their connection with reputable players and negatively affects their legitimacy as entrepreneurs (Avnimelech and Rechter Citation2023; McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019).

Given this, the creation of formally established networks for women entrepreneurs as a top-down initiative represents an attempt to create for them the support generated for men by their informal same-sex groups (Gavara and Zarco Citation2015). This arises from the view that women entrepreneurs and would-be entrepreneurs have not been socialized appropriately to compete in a man’s world, require ‘fixing’ by specific policy interventions (Ahl and Marlow Citation2012; Ely and Meyerson Citation2000; McAdam Citation2022) to provide them with appropriate entrepreneurial tools and skills. Most research on entrepreneurial networking has focused on the creation and functioning of entrepreneur centred, informal networks and on the ego-alter relationships within these (Jack Citation2005; Jack, Anderson, and Drakopolou Dodd Citation2008; Shaw et al. Citation2009). However, there have been far fewer studies of formal entrepreneurial networks, despite their prominence as an instrument of economic development policy, and, in particular, of gendered differences in their membership (Das and Teng Citation1997; Lefebvre, Radu Lefebvre, and Simon Citation2015; Malewicki Citation2005).

The aim of this paper is to add to this scant literature, by investigating the experiences of women entrepreneurs who have joined formal networks, as an illustration of the extent to which Bourdieu’s theory of embodied practice provides a deeper understanding of entrepreneurial action and experience. Commentators have identified a widespread ‘pragmatic approach to Bourdieu’s work, one that considers it legitimate to pick and choose concepts, as opposed to adopting the whole package’ (Lamont Citation2012, 228–229). As we show in the next section, this is certainly the case in entrepreneurship. In reacting to this, our intent is to complement the current use of Bourdieu’s ‘thinking tools’ as we seek to put Bourdieu to work, in the spirit of his own emphasis on theory-method rather than theory alone, to ‘evoke his concepts as tools for thinking [our] way into empirical realities’ (Gale and Lingaard Citation2015, 1). As such, we use both his theory (and in particular his notion of habitus) and do theory, in the sense of pushing the boundaries of current theoretical knowledge and co-develop our arguments as a dialogue between the literature and our research context.

Entrepreneurship as a gendered social practice

In recent years, there has been an upsurge of interest in and application of Bourdieu’s theory, or socioanalysis, of practice across the social sciences in general (Costa and Murphy Citation2015) and as part of the recent practice turn in entrepreneurship in particular (Champenois, Lefebvre, and Ronteau Citation2020; Thompson et al. Citation2022). Driven by the desire to transcend a number of interconnected dichotomies (e.g. theory/practice, subjective/objective, structure/agency), Bourdieu developed some ‘thinking tools’, including field, habitus, capital, doxa, illusio and symbolic violence. We build on existing Bourdieusian approaches to entrepreneurship as a social and economic process embedded in complex networks of resources, power relations and institutions (Anderson, Dodd, and Jack Citation2010; De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009a, Citation2009b, Citation2009c; Hill Citation2018; Karataş-Özkan Citation2011; Nijkamp Citation2003; Scott Citation2012; Spigel Citation2013; Vincent Citation2016; Vincent and Pagan Citation2019), to develop a theoretical framework based on feminist interpretations of Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Bourdieu Citation1977, Citation2000; McNay Citation2000).

The starting point for this analysis is that, in contradistinction to the agentic individualism of neoliberalism, ‘work’ in contemporary society is regulated by a set of inherited and pre-existing social structures which shape the institutional field of professional identity, including entrepreneurial identity. We apply Bourdieu’s notion of field, as an organized site of force and struggle which actors attempt to transform in the struggle for legitimacy (Pileggi and Patton Citation2003), to the practice of entrepreneurship as a domain in which actors manoeuvre and struggle in pursuit of desirable resources, through the acquisition of different types of capital. In so doing, we acknowledge Bourdieu’s understanding of the social world as comprising differentiated but overlapping fields of action (the economic, the political, the legal and so on) each of which has its own logic or habitus as embodied social practice over time which informs and sets limits on practice, naturalizes and normalizes as doxa the cultural and symbolic roles embodied in the world of gendered work, and is evoked as illusio, the commitment of ‘players’ in the field to invest in its stakes, that is, its objects of value, and to believe in the significance of the game and the benefits it promises (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992).

We investigate this theorization of the role and importance of pre-existing structures in shaping gender relations in the context of formally established networks, both women-only and mixed-gender, as arenas in which women entrepreneurs can become acculturated into the field and learn its values, rules, and dynamics. Specifically, we examine the role gender plays in shaping how, if at all, women become credible field players through their membership of formal networks.

In terms of Bourdieu’s thinking tools, much of Bourdieusian research in entrepreneurship to date has focused primarily on economic, cultural, social and symbolic capital (Light and Dana Citation2013; Nowicka Citation2013; Pret, Shaw, and Drakopooulou Dodd Citation2015; Shaw et al. Citation2009), and on social capital in particular, drawing only, in many cases, on Bourdieu’s (Citation1986) essay on ‘the forms of capital’ (Batjargal Citation2003; De Carolis, Litzky, and Eddleston Citation2009; Ferri, Deakins, and Whittam Citation2009). Furthermore, much of this research makes only passing reference to Bourdieu to establish a focus on social capital (Bird and Wennberg Citation2014; Davidsson and Honig Citation2003; Foley and O’Connnor Citation2013; Román, Congregado, and Millán Citation2013; Stam, Arzlanian, and Elfring Citation2014) or cultural capital (Fairchild Citation2010; Meek, Pacheco, and York Citation2010; Spigel Citation2017; Wright and Zammuto Citation2013). This is also consistent with the concept of gender capital as embodied cultural capital in feminist readings of Bourdieu (Lovell Citation2000; McCall Citation1992; Reay Citation2004; Skeggs Citation1997, Citation2004). Extended by Huppatz (Citation2014, Citation2009, Citation2010) to differentiate female (gender advantage derived from the perception of having a female body) from feminine capital, gender capital can help understand gendered occupational practices, explain how gender inequality and privilege operate in particular types of work and the intersectionality of gender, class and occupation (Huppatz Citation2012). Gender capital is embodied (historically contingent and context-dependent dispositions cast as masculine and feminine), objectified (in the form of material and immaterial objects that are endowed with gendered properties in everyday practice) and institutionalized (such that production tasks, valorization devices and labour outputs are embedded in relational and asymmetrical conceptions of femininity and masculinity) (Matos Citation2018).

Relatively less attention has been paid to his concepts of habitus, field – ‘although it lies at the heart of his work’ (Hilgers and Mangez Citation2014, 1) – doxa, the understanding of what is being played out in a field and the basis for the relationship between the players in that field, and illusio, (or ‘interest’), as the interest individuals have which is defined by their circumstances and allows them to ‘act in a particular way within the context in which they find themselves’ (Bowman Citation2007; Drakopoulou Dodd et al. Citation2014; Grenfell Citation2014a, 152; Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023; Patel and Conklin Citation2009; Seidl and Whittington Citation2014). Recent exceptions are Vincent’s Citation2016 examination of the temporal structure of the field and how this affects access to capital(s) and of the ‘man’s world’ of the entrepreneurship domain, and the application of Bourdieu’s concepts of field and habitus (but not doxa) to the study of entrepreneurs’ digital networks (Smith, Smith, and Shaw Citation2017), which highlights the importance of habitus in shaping the context for networking behaviour (Anderson, Dodd, and Jack Citation2010; Anderson, Park, and Jack Citation2007; De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009c; Keating, Geiger, and McLoughlin Citation2014; McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015).Footnote1

Fields are the social spaces in which individual agency, through interactions, transactions and events, comes into play, each of which has properties that are the focus of strategic decision-making characterized by an ongoing struggle between a community of actors for unequally distributed resources in the form of different types of capital that can be acquired, converted and/or traded (Shaw et al. Citation2009; Vincent Citation2016). Each field is constituted by a durable network of social relations which is in constant evolution as actors compete for possession of the most appropriate forms of capital (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992) which is ‘essential for getting ahead’ (Vincent Citation2016, 1167), motivates actors’ practice and underpins the field’s structuring principles and relations (Laberge Citation1995). These social relations in turn rely on actors implicitly agreeing to follow ‘the rules of the game’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992; Bourdieu, Citation1990a) by internalizing the field’s structures, modus operandi and hierarchies into their habitus or socialized subjectivity. The struggle for ownership of capital is the precondition of playing the game and the determinant of an actor’s position in the field. Thus, it is important for actors to develop a sense for how a field operates and to understand their place in it. Habitus, internalized via enculturation, provides each actor with a mental schema and an embodied understanding of the field’s rules and how these might be applicable given their status and position (McLeod Citation2005; Tatli et al. Citation2014). Representing the ‘individual embodiment of shared meaning systems’ (Vincent Citation2016, 1167) habitus is a useful means by which to explain how fields are differentially experienced and enacted.

For Bourdieu, there is an intrinsic interplay between field, capital and habitus such that membership of a field is a para-doxal commitment to a set of presuppositions (doxa) that shapes action and behaviours (Bourdieu Citation1977, 1990; 2006; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Grenfell (Citation2014a) distinguishes between field mechanisms (such as capital and doxa) which are objective structures, a medium of operation reflected in features which arise from their procedures, and field conditions (such as interest/illusio and symbolic violence) which are subjective representations of how fields are present in individuals and their repercussions. Doxa, the set of rules in a specific field, defines what is thinkable and what is capable of being said (Bourdieu Citation1977, 1990; 2006; Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). The ability to effectively operate in a field requires an actor, in this case an entrepreneur, to understand the prescribed rules of the game and how to operate within them. This has a specific implication: ‘the homology between the spaces of positions and the space of dispositions is never perfect and there are always some agents “out on a limb”, displaced, out of place and ill at ease’ (Bourdieu Citation2000, 157). This is consistent with Lane’s (Citation2000) analysis of the three roles of doxa: first, it gives actions a sense of purpose and meaning; second, it ensures a time and place for everything; and third, it naturalizes and legitimizes the social roles adopted by different classes, age groups and genders. In other words, doxa is the tacit taken-for-granted aspect of social life, the feeling that actors can and ought to do no other than what they are doing. It happens when we ‘forget the limits’ that have given rise to unequal divisions in society: in essence, it is ‘an adherence to relations of order which, because they structure inseparably both the real world and the thought world, are accepted as self-evident’ (Bourdieu Citation1984, 471).

These ‘thinking tools’ reflect Bourdieu’s ontological rejection of the binary dichotomy between structure and agency (Martin and Denis Citation2016; Sterne Citation2003; Vandenberghe Citation1999) and his insistence that both entail ‘bundles of relations’ (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 161). There is, of course, a danger that this risks a conflation of structure and agency: for example, fields have properties that are relationally emergent from the articulations of agents and so are not properties of individuals, and our concept of margins of intervention allows for the power of agency to transform and contest local doxa, and so agency does not necessarily conform to routine. The relationship between structure and agency in Bourdieu, and the central conflation of structure and agency that this formulation risks, has been criticized from a critical realist perspective that sees agency as a quality inherent in human subjects which participates in both social representation and social change (Archer Citation2012). However, Archer’s critique is overstated, and she does recognize in practice that anchoring the different forms of reflexivity and the formation of concerns in different social contexts (as she does) is in effect describing the formation of habitus under a different name, leading one commentator to conclude that ‘far from supporting the critical rejection of Bourdieu, her analysis nicely captures the detail and mess of habitus formation “on the ground” in twenty-first-century Britain’ (Atkinson Citation2014). Given this, the ‘bundle of relations’ perspective suggests that agency must be understood in relational terms rather than in the ontological sense as the absolute grounds of social being (McNay Citation2004): it is located not in any essential properties of ‘the subject’ or in the possession of resources (capital) but in the production of different affective capacities through the assemblages that produce human beings (Threadgold, Farrugia, and Coffey Citation2021). Agency and structure, on this view, are not a binary either/or, neither are they conflated into one construct, and agency is best viewed as part of a person’s continued process of engagement with the world. Agency, on this view, is not a capacity inherent in the subject but can be thought of in terms of the capacities produced through social arrangements.

If the field designates any social space, and its practices reflect both structure (being positioned) and agency (self-positioning), then its corollary is habitus as the expression of the combination of socially structuring dispositions and socially structured predispositions. Together, habitus and field illuminate the ways in which particular social groups engage with practice and their differentiated trajectories within fields that are inherently competitive and unequal (Colley and Frédérique Citation2015). This suggests that based on the knowledge of the field rules actors can make a number of choices in order to achieve their objectives, choices that are shaped by their experience and habitus. By choosing to imitate practices they observe they can follow the rules of the field more closely in order to be successful (Spigel Citation2013). Habitus, thus, shapes how women entrepreneurs act and respond according to the rules of the field. They draw on capital to improve their field position and in so doing can enhance their standing with respect to others, gaining credibility as a player in the field. As women entrepreneurs may be considered interlopers in the entrepreneurial field (Ahl Citation2004, Citation2006), a Bourdieusian analysis of habitus and field aids a more nuanced understanding of how they acquire understanding of it and how they negotiate and navigate their pursuit of credibility and legitimacy (De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009a).

Habitus and field are inseparable concepts, articulated together by illusio (Gouanvic Citation2005; Warde Citation2004) as the commitment of players in any field to invest in its stakes, its objects of value: ‘We have stakes (enjeux) which are for the most part the product of the competition between players. We have an investment in the game, illusio (from ludus, the game): players are taken in by the game, they oppose one another, sometimes with ferocity, only to the extent that they concur in their belief (doxa) in the game and its stakes; they grant these a recognition that escapes questioning. Players agree, by the mere fact of playing, and not by way of a “contract”, that the game is worth playing, that it is “worth the candle”, and this collusion is the very basis of their competition (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992, 98)’.

One of the challenges for entrepreneurial research, to which we respond to in this paper, is that of shifting the focus from the field-level structural argument to the micro-level of individual behaviour (Ozken and Eisenhardt Citation2009; De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009a; McKever et al. Citation2015), and to do so in a wider range of contexts, including the analysis of gendered entrepreneurial action (to date focused on capital as a field mechanism – e.g. Marlow and Carter Citation2004; Shaw et al. Citation2009; Vincent Citation2016; Vincent and Pagan Citation2019) that have not been the primary focus of Bourdieusian entrepreneurship scholarship to date (McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019).

Research context and design

We adopt an interpretive approach that sees research as a dialogical process between theory and empirical observation, in which the researcher’s judgement (cognition) plays a crucial role in interpretation, and in which the intent is the development of reflexive narratives not explanatory models or theoretical propositions (Manteri and Ketoviki Citation2013, 75; see also Ketokivi and Mantere Citation2010). As such, this has much in common with an abductive approach which as a recursive process requires both in-depth familiarity with theory and an intensive engagement with observations, in which negotiating the tension between knowing what you are interested in and remaining open to new unexpected findings is central to the research process (Timmermans and Tavory Citation2022). This has been informed by three specific characteristics of a Bourdieusian perspective on research design and data collection (Grenfell and Lebaron Citation2014). First, we avoid simply describing the data in terms of Bourdieusian concepts (a kind of metaphorization of data reflected in ‘the contemporary fashion of overlaying research analyses with Bourdieu’s concepts’ (Reay Citation2004, 431–432)). Instead, we construct the research object, that is, women’s experience of participating in formal business networks, in terms of the identification of relations and their consequences, to bring fresh insight to the topic. Following Bourdieu’s distinction between ‘objectivation of the first order’ (the analysis of objective relations in the field of study) and ‘objectivation of the second order’ (the phenomenological investigation itself), we summarize the character and efficacy of the networks analysed and the disparity and disadvantage of women in this field they seek to address as a basis for the contextualization of our research.

Second, in constructing the research object and rethinking it in a new way (Bourdieu Citation1990a) we highlight the reflexive relationship between us, as researchers, and our research, recognizing that our own ‘feel’ or ‘eye’ is a critical source of knowledge, which can benefit from an empathetic resonance between the researcher and the researched (Sklaveniti and Steyaert Citation2020). Bourdieu, in his discussions of objectivity and subjectivity, the logic of practice in relation to the scholastic point of view, and the relation of praxis to societal transformation, turns attention to our own taken for granted commonsense understandings (Adkins Citation2004) and highlights that it is vital to be ‘aware of our own “locations” in the fields of possibilities as well as those of our subjects of research’ (Reed-Danahay Citation2005, 159), recognizing that reflexivity is ‘more than a pragmatic option; it is rather an epistemological necessity’ (Grenfell Citation2014b, 224).

Third, given the difficulty of capturing a social discourse in all of its multidimensionality, and recognizing that research is a ‘responsible act’ (Bourdieu Citation1990a), we use power quotes (Pratt Citation2008, Citation2009) drawn from participants’ narratives to effectively illustrate our points in a dialogue between the Bourdieusian literature and our research context (Matos Citation2018, 3). While this does not fully overcome the researcher’s unconscious, implied and occluded presuppositions (arising from their particular position in the social space, the orthodoxy of the scientific field itself and the whole relation to the social world –Bourdieu Citation2000), it does help the researcher and the reader to situate themselves in a social space at the same point as the respondent. It does not, however, sublimate the distance between our learned reconstruction of the respondents’ world and their experience of that world. In short, our research design is built on a philosophical base of epistemologically charged analytical constructs and an empirical approach which, following Bourdieu, is structural, relational and dynamic and is based on an openness to see beyond the conventional ways of interpreting the site-specific contexts of the social world (Grenfell and Lebaron Citation2014). Following Bourdieu (Citation1999) we view these as ‘places of kaleidoscopic experience’ which can both include and exclude (Boyne Citation2002, 125).

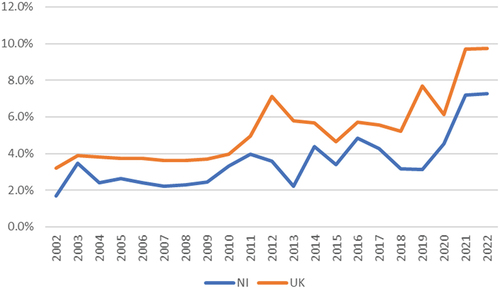

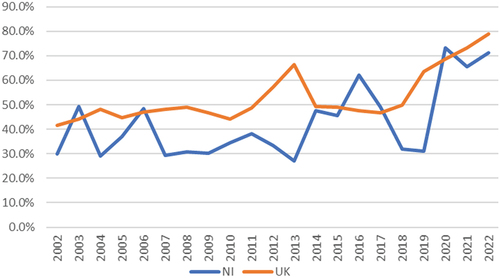

In terms of contextual framing (Baker and Welter Citation2018), the setting for this research is Northern Ireland, a UK region with a particularly weak economic position and low rates of entrepreneurship in general, and female entrepreneurship in particular (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020; Hart Citation2008; Hill, Leitch, and Harrison Citation2006; Leitch, Harrison, and Hill Citation2015a, Citation2015b). Levels of women’s entrepreneurship in the region have consistently been significantly below the UK national average, and the gap has only closed somewhat during the recession (). Furthermore, average ratios of female to male entrepreneurial activity from 2002 to 2022 have also been lower in Northern Ireland: 43% in Northern Ireland compared to 53% in the UK, although the NI/UK gap has closed in recent years ().

Figure 1. Total early-stage female entrepreneurial activity in Northern Ireland and the UK, 2002–2022.

Figure 2. Total early-stage female entrepreneurial activity as a percentage of male in Northern Ireland and the UK, 2002–2022.

In response, the regional development agency has introduced initiatives to stimulate female entrepreneurial activity and wealth creation (Marlow, Carter, and Shaw Citation2008) to increase the critical mass and quality of start-ups by women through addressing the structural and cultural obstacles that traditionally limit female entrepreneurial activity (Conlon and Stennett Citation2015; Fleck, Hegarty, and Neergaard Citation2011; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020). InvestNI, the regional development agency, is fundamentally committed to belief in the efficacy of women’s entrepreneurship: they have ‘a very positive view of entrepreneurship as a career choice … [and] … increasing the level of entrepreneurial activity among women will make a huge contribution to the diversity and success of the local economyFootnote2’. In so doing, they inadvertently demonstrate the ‘othering’ of women’s entrepreneurship and the superficiality of analysis and policy development (Stewart and Logan Citation2023) by describing it in terms that would never be applied to their male counterparts: ‘Many women work part-time while setting up a business. This gives them the chance to develop their business idea while reducing the financial risk that may be involved. … Others work flexible hours in their new business to allow them to look after a home or fulfil other commitments while getting the business off the ground … Setting up a business is an exciting career option that is flexible and open to anyone. So, whether you are currently working, are taking a career break or are just starting out, you can find help to make your business idea a reality’.

One specific initiative, the focus for our analysis, was the introduction of subsidized, formal women-only business networks which were established to compensate for the absence of informal networks and thus offer nascent and more experienced female entrepreneurs’ access to relevant knowledge, expertise, support and role models. In a direct embodiment of the ‘confidence culture’ (Orgard and Gill Citation2022), InvestNI advise their prospective women entrepreneurs that ‘If you feel nervous about setting up a business, that’s normal for everyone – don’t let that put you off. A good way to build your confidence is to speak to others who have set up a business and find out what the experience is really like’. They continue: ‘If you are a woman considering setting up a business, you will boost your chances of success by accessing the right networks and mentors. These are women who can share their experience of business with you and people who understand the needs of female entrepreneurs. … Women’s business networks are a good way to build relationships. They offer a forum for discussion, sharing experiences, peer mentoring and practical and emotional support. Just knowing someone else is facing the same challenges as you, makes it easier to keep going. … Networking is a highly effective way to build up a business. It offers a potential market for your goods or services and can be an invaluable way of building up a client base and track record. … [Networks] … are aimed at helping women develop both personally and professionally, make connections and ultimately grow their business’.

Given this policy background, we investigate women entrepreneurs’ lived experience of membership of formal business networks, as a route to accumulate capital, develop understanding of the field and gain insights into the rules of the game. However, research has consistently demonstrated the gendered nature of networking and networks (Foss Citation2010; Neergaard, Shaw, and Carter Citation2005; Renzulli, Aldrich, and Moody Citation2000), with women tending to use networks for social support while men are more instrumental in promoting their careers (Ibarra Citation1992; McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019). Given these differences, the creation of formally established networks for women entrepreneurs represents an attempt by policymakers to create for them the support men enjoy through their informal same-sex groups and to provide them with appropriate entrepreneurial knowledge, tools and skills and capabilities (Fritsch Citation2011; Gavara and Zarco Citation2015).

Data collection and analysis

Our approach to sampling was purposive (Gartner and Birley Citation2002; Neergaard Citation2007; Pratt Citation2009) and theoretical in having the characteristics that fitted our investigation (McKeever, Jack, and Anderson Citation2015). While we recognize that women who join formal entrepreneurship networks may have already perceived some bias towards them, and therefore, may not be typical of the wider population of female entrepreneurs, nevertheless our interest in understanding the impact and effectiveness of such networks requires a focus on their members. Therefore, we make no universalist claims for the applicability of our research findings for women entrepreneurs in general, nor do we address the efficacy of informal vis-a-vis formal networking.

We contacted and interviewed the managers/coordinators of all 11 identifiable formal business networks in the economic field, six of which were women-only networks established as part of the regional entrepreneurship strategy. Each manager facilitated access to their members, who were invited to participate in interviews with a member of the research team. We secured the participation of 17 women entrepreneurs, drawn from five networks, three women-only and two mixed-gender. The women-only networks are relatively small, have nominal membership fees and are administered by part-time coordinators who are also entrepreneurs. The mixed-gender networks are longer established and larger with a more diverse membership base and employ full-time, dedicated staff (). Data were collected from nascent entrepreneurs whose businesses were aged less than 3 years (n = 8) (Aldrich et al. Citation1987), and more experienced individuals with businesses aged 3 years or more (n = 9) (). We chose to use these two categories to explore the extent to which women’s experience of participation of formal networks changes with the maturity of their business and their experience. This allows us to develop a more nuanced insight into the role of doxa (and its interrelations with habitus, field, and capital) in accounting for women’s entrepreneurial behaviour and actions.

Table 1. Background and purpose of the networksFootnote4 studied.

Table 2. Details of nascent business owners.

Table 3. Details of established business owners.

Following Talmy (Citation2010a, Citation2010b) and Liuberté and Feuls (Citation2022) we identify two perspectives on interviewing. The first is to see the interview as a research instrument and tool for collecting information from research participants, in the form of facts, attitudes and other cognitive representations, the analysis of which allows the data to ‘speak for themselves’ as a reflection of reality. The second perspective, by contrast, sees the interview as a social practice which is not a free-standing technique but a participatory encounter that invokes ‘the interactional, multimodal, narrative and indirect elements and contexts that are brought into action’ (Liuberté and Feuls Citation2022, 261) in the reflective co-creation of knowledge. From this perspective, the collection of personal interview narratives, following Bourdieu (Citation1999), allows access to understandings that go beyond the doxa, and treats interviewees as ‘practical analysts’ situated at points of contradiction in structures who in order to ‘survive’ develop a form of self-analysis which can give them access to the objective contradictions which have them in their grasp and to the objective structures expressed by and in these contradictions (Bourdieu Citation1999, 511). These narratives are not, of course, unproblematic (Goodman Citation2003; Reed-Danahay Citation2005, 130–131): even the best-informed informant ‘produces a discourse which compounds two opposing systems of lacunae. Insofar as it is a discourse of familiarity, it leaves unsaid all that goes without saying … Insofar as it is an outsider-oriented discourse it tends to exclude all direct reference to particular cases … [we] … so often forget the distance between learned reconstruction of the native world and the native experience of the world, an experience which finds expression only in the silences, ellipses, and lacunae of the language of familiarity’ (Bourdieu Citation1977, 18).

We conducted semi-structured interviews of on average one and a-half-hours at the network venues. Two members of the research team recorded the interviews that were transcribed verbatim and took field notes.Footnote3 In total, we generated 1898 min of interview recordings representing 70, 264 words of transcript over 109 single-spaced pages. The resulting narratives, using pseudonyms, were treated as archetypal sense-making tools to reveal how our participants think and act as well as providing detailed insight into their worldview (Czarniawska Citation2004). Language through narrative provides a mechanism for social actors to make sense of their world and identifies the taken-for-granted assumptions that inform and limit their entrepreneurial thinking (Down and Reveley Citation2009; Holt and Macpherson Citation2010; Watson Citation2009). Throughout we were careful to ensure that we sought understanding and explanation of the women’s networking behaviours, as far as possible to see the world from their point of view. Accordingly, we avoided both an unwarranted form of objectivism and a weak constructivism-based form of relativism as we sought in Bourdieu’s phrase, the ‘democratization of the hermeneutic’ (Grenfell and Lebaron Citation2014). Following the procedures set out in Leitch et al. (Citation2010) and Gioia et al. (Citation2013), we sought to ensure the trustworthiness of our data in two ways. First, we ensured the accuracy of our interpretations via follow-up interviews 6 months after the initial interviews, each lasting 40 min with our participants (n = 28) (Morse Citation1991); and second, as demonstrated below, we enable other researchers to determine the methodological veracity of our study by providing a traceable chain of evidence (Pratt Citation2009).

The transcripts provided a rich source of data in which understanding of the entrepreneurial environment (the field), the requirement to learn and play the rules of the game, the women’s own interpretation of these and their acquisition and conversion of capital, were evident. We adopted a reflexive critical methodology (Stead and Hamilton Citation2016; Vincent and Pagan Citation2019) that specifically challenges the normative and focuses on the context in which the micro-practices and relational dynamics of everyday life are embedded (Alvesson and Deetz Citation2000), foregrounding the relationship between those who are dominant and those who are not (Calàs, Smircich, and Bourne Citation2009). We conducted two cycles of analysis and employed four categories (field, capital, habitus and doxa) to assist us. During each cycle, we read and re-read the narratives closely for examples of the different ways in which the women understood the field’s rules and their impact on their entrepreneurial practice (Gioia Citation2020; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013).

In the first cycle, we ascertained the interpretive potential of the narratives, providing a broad overview of how women negotiated their way around the field, how they perceived it and the strategies they adopted to play the game and acquire capital. We began by identifying statements regarding our participants’ views of the world and drew on common statements to produce provisional categories and first order codes, comprising phrases, terms or descriptions used by the participants. After codes were named and categories were constructed, we reviewed the data to see which, if any fitted each category. Sometimes the revisited data did not fit with a constructed category, resulting in either the abandonment or revision of a category. This cycle also involved the integration of first order codes and the creation of theoretical categories, thus signifying the transition from open to axial coding (Locke Citation2001). This was a recursive rather than a linear process as we moved iteratively between the first order categories and the emerging patterns in our data until adequate conceptual themes emerged (Eisenhardt Citation1989).

Once these theoretical categories had been generated, the second cycle of analysis involved a more critical interpretation of the findings as we examined the narratives for evidence of the gendering of Bourdieu’s embodied theory of practice. Thus, we used ‘theory’ to interpret, as it were, the social world of the ‘woman entrepreneur’ and treat theory as a perspective, a ‘point of understanding to sort out the buzzing confusions and complexities of the social world’ (Spicer Citation2008, 47). As such, the moment of doing theory becomes not one of establishing causal relations to predict behaviours and outcomes, but one of trying to generate a meaningful understanding of the entrepreneur’s world. It is, in other words, an effort to understand and recover their patterns of meaning and interpretation of actions, to root out the practical knowledge of the actors as they go through the social world. The outcome is that by ‘grounding knowledge in people’s experiences and emotions and, simultaneously, connecting these with new ideas about what is happening, a new sense of what is “real” is constructed’ (Ramazanoğlu and Holland Citation2002, 43). We then organized the resultant theoretical categories into aggregate theoretical dimensions (Corley and Gioia Citation2004; Maitlis and Lawrence Citation2007). This illuminated incidents where gender was produced and re-produced within the women’s reflections, thus challenging the apparently gender-neutral nature of Bourdieu’s theory of embodied practice. Our final Data Structure Table is presented in .

Table 4. Data structure: inductive analysis and data coding.

This reflexive critical approach allowed us to obtain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the impact of gendered relations on women entrepreneurs’ experiences resulting in the development of a gender aware Bourdieusian perspective on field, doxa, illusio, habitus and capital, which we now discuss.

Findings: woman’s entrepreneurship as a contested space

Our emergent framework comprises three dimensions of women’s experience of the field of entrepreneurship. First, we demonstrate how the entrepreneurship field is differentiated by gender, such that habitus is formed in the midst of and structured by differential relations of power and unequal distribution of capitals. Second, we identify the importance of gender habitus, where dispositions are gendered, inherited and manifest in an embodied way of being which is shaped by interaction with the field. Third, we uncover the important role of doxa and illusio, as the participants’ commitment to and belief in the rules of the game. As we will show below, this framework provides a valuable means of demonstrating the manner in which gender influences women’s participation in entrepreneurial activity.

Field differentiated by gender

In the everyday practice of engaging with entrepreneurship, there was unquestioned acceptance that men dominated the key field positions: ‘entrepreneurship is still a man’s world’ (Mary) while for Patricia it ‘is very much a man’s environment … you have to break into that and as a woman it’s very much pushing your way through’. These women accepted the masculinity of entrepreneurship, their role in it and even demonstrated an eagerness to know the rules of engagement (Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020; McAdam, Harrison, and Leitch Citation2019). However, it was evident that nascent entrepreneurs joined the women-only networks to counteract this masculinity, to improve their social capital by engaging with other likeminded women and to reduce the gender or entrepreneurial isolation associated with business ownership: “I think when you are in business on your own it is reassuring to talk to other people … because you do get a bit isolated (Cathy), while Angela noted that you get ‘A lot of emotional support … .especially if you are a sole trader that you are out mingling with other people’. This is consistent with the concept of gender capital as embodied cultural capital in feminist readings of Bourdieu (Lovell Citation2000; McCall Citation1992; Reay Citation2004; Skeggs Citation1997, Citation2004). In other words, gender capital may empower women and provide them with a sense of agency to develop and sustain their careers (Huppatz Citation2009). However, there is little evidence in the lived experience of our nascent women entrepreneurs to suggest that this gender capital has currency elsewhere in the entrepreneurship field.

This is reinforced in the experience of more established women entrepreneurs, for whom the motivation for joining mixed networks appeared to be the opportunity to undergo a social process of cultural alignment into the field by which to emulate certain behaviours of knowledgeable field players in the entrepreneurship arena in the hope of attaining credibility. As Maureen observed, it is essential to ‘get a leg up’ as ‘on your own you can only go so far before hitting another wall’, while for Hilary, ‘it was imperative to join XXX, it was not a question of do I like them, it needs to be done because an awful lot of business is about credibility’. While gender capital has the potential to disrupt the field, in this case entrepreneurship, by helping women draw on their feminine dispositions to negotiate and navigate its boundaries as capital-wielding subjects (Ross-Smith and Huppatz Citation2010), these boundaries have been established by, and the field continues to be dominated by, men, and these outcomes do not challenge the masculinist power regimes that dominate the field (Skeggs Citation1997).

Once in the field, the women referred to the struggles for positions, for instance, observing in mixed-gender networks how men were ‘jockeying for position’ in the field’s hierarchy. Karen, (a nascent entrepreneur and member of a mixed network) noted that she ‘ … hadn’t realized that there would be so much jockeying for position – it has been a real wakeup call’. Despite acceptance that the key positions were held and would always be held by men, it was still deemed important to know who occupied particular positions: ‘You know who’s the head, who’s in the committee, who’s the proactive people – you are very much aware of them’ (Patricia). ‘Before joining XXX I did some mapping – to get a sense of who is out there and what they are about … ’. (Joanne). Based on the lived experience of both nascent and established women entrepreneurs there is a clear recognition of the extent to which the field is differentiated by gender. This qualifies and constrains the extent to which gender capital, as theorized in feminist appropriations of Bourdieu, can actually transform women’s positioning within the field (Matos Citation2018). In other words, our evidence suggests that women do not have access to enough economic, political, social and symbolic capital to force a redefinition of the requirements of the field (Corsun and Costen Citation2001): the outcomes of wielding (feminine or female) gender capital are not constitutive of transformation (as would be evidenced in overturning the power relations of the field) but merely tweak at the edges in ways that are tactical rather than strategic (Ross-Smith and Huppatz Citation2010).

Gender habitus

When entering a field, an individual has their habitus, the embodied ‘feel’ for the social situation, which facilitates the successful navigation of social environments (Bourdieu, Citation1990b; 1994). Due to the persistent gender bias in entrepreneurship discourse women entrepreneurs, unless they acknowledge or subscribe to normative masculine standards, will continue to be viewed as lacking or as incomplete men (Ahl Citation2004, Citation2006; Marlow and Martinez Dy Citation2018). One of the ramifications of this, is that women, may not have an apt feel for the game: ‘Women just don’t know how to play the game right’ (Hilary), while Fiona remarked ‘it is still a man’s world in business but at least if you are a business owner there is no glass ceiling because you are your own boss but now I’ve changed my mind slightly because in the network you realize you’re up against other issues’. In other words, for some of our respondents there was a recognition that the position of social actors in the field resulted from the capital they had accrued. Capital accrual and capital accrual strategies determine one’s position, so those with more abundant capital had more dominant positions within the hierarchical structure of the field.

Accordingly, obtaining this feel for the field in order to be deemed credible players, and accruing the capital necessary to support this, is particularly challenging for women. Our respondents recognized this challenge and tried to address it through formal network membership; specifically highlighting the importance of joining a mixed-gender network. For example, Joanne observed that ‘It (a women-only network) can be very limited, in that there are very few people that can help you get to the next level. So that’s where you have to go into the mixed bag of affairs – the male and the female!’ For Elaine, the benefits of a mixed-gender network was through the mentoring it afforded as it provided insights into masculine taken-for-granted norms: ‘the mentoring in XXX is absolutely brilliant, I get to think like a man’. In deliberately seeking out opportunities to assimilate into the field and to gain insights into its modus operandi, women shape their habitus and in turn their subsequent entrepreneurial actions and behaviours as entrepreneurs (Reay Citation2004). In other words, the nascent entrepreneurs were more naïve in their motivations for joining networks. By looking for opportunities to socialize, to reduce isolation and to be part of something they were potentially enhancing their social capital only, which could detrimentally impact their field position. In other words, there was a lack of strategic hierarchical positioning, both internally within networks and externally between them.

By contrast, the established women entrepreneurs, with their more highly developed and attuned habitus, were conscious of the structuring of the field and employed their own capital accumulating strategies in an attempt to increase their position in it. ‘I joined XXX as I knew it would have the movers and shakers’ (Mary) resulting in the mixed-gender networks ‘being very driven and a bit pressurized’ (Joanne). In contrast, the nascent entrepreneurs, with a less developed sense of habitus, were not as aware of the field’s hierarchal positioning and thus less likely to engage in capital accumulating strategies to aid their field positions. Instead, they saw networks, including those which were mixed, as a way to reduce isolation and increase socialization: ‘I think when you are in business on your own it is reassuring to talk to other people … because you do get a bit isolated’ (Gillian), while Susan observed, ‘It’s just a relief to talk to other women. The women only thing, I suppose it like being part of a sisterhood type of thing’. Despite the benefits identified in terms of reducing isolation there was concern that women-only networks were perceived as ‘a talking shop for women’ (Ann) or for Cathy, ‘The women-only thing, I suppose it like being part of a sisterhood type of thing’. In addition, they were considered inferior to the mixed-gender networks, “I know lady friends of mine and men refer to it (women-only network) as ‘have you got your women’s meeting tonight?’ (Louise) or as Helen remarked, ‘The women’s network, it sounds a bit WI (Women’s Institute) doesn’t it … ?’. Membership of a mixed-gender network, on the other hand, appeared to facilitate the accrual of symbolic capital, as summed up by Hilary ‘It’s part of my business and needs to be done because an awful lot of my business is about credibility … what I find with XXX (mixed group) is that they are very helpful in building a presence for you’. Network membership can therefore result in different accumulations of symbolic capital, which in turn can produce or reproduce inequality within the field.

Doxa, Illusio and symbolic violence

The discussion of gender capital and habitus, as evidenced by the lived experience of our respondents, goes some way to account for their position in the field. A deeper understanding comes from consideration of how these women develop a sense of the game. This is an important factor for Bourdieu and network membership endows women entrepreneurs with a better feel for it. However, given that entrepreneurship as a social field of practice is suffused with masculinity that defines and limits the underpinning discourse, it remains pertinent to ask, ‘How do some women manage to develop a good feel for games from which they are excluded by virtue of their sex?’ (Lovell Citation2000, 14). Part of the answer can be found in a more detailed consideration of role played by doxa, the process through which socially and culturally constituted ways of perceiving, evaluating and behaving become accepted as unquestioned, self-evident and taken for granted (Throop and Murphy Citation2002, 189). Regardless of their self-perceived position in the field, the women in mixed-gender networks seem to share an acceptance of it, their role in it and the rules of engagement, which served to privilege the male experience. This was reinforced by the recognition, ‘they [men] have their own language and us women need to be able to speak it’ (Patricia). Indeed, to be deemed credible the women highlighted the importance of conforming to the stereotypical image of the entrepreneur (De Clercq and Voronov Citation2009b); ‘either your face fits or it doesn’t’ (Nuala).

Doxa tends to privilege the dominant players by taking their position of dominance as self-evident and universally favourable (Deer Citation2014; Duggin and Pudsey Citation2006). Our respondents were aware of this, for as Mary commented ‘you are not appointed, you’re anointed by the powers that be’, while Maureen highlighted, ‘it (entrepreneurship) is predominately controlled by men’. This is not confined to acknowledging actors’ positions in the field’s hierarchy but is reinforced by the decisions made, even apparently minor ones such as where to hold a networking event. For example, Nuala noted, the ‘very fact that meetings are in the XXXX [former Gentlemen’s] Club, puts a particular spin on it’. In fact, holding meetings in a venue, which has been the home of a long-established, members-only private club, originally set up by and for professional and businessmen, subjects women to symbolic violence, the recognized legitimation of power, influence, prestige and honour.

The importance of gaining knowledge and understanding of the rules of the game was apparent among the more established entrepreneurs, who were strategic in identifying the key players in the field. ‘It’s a massive game, which you have to learn the rules. A mixed group that is where you learn rules of the game’ (Patricia). Based on this, actors can then make a number of choices to achieve their objectives. In this case, it appeared that the women choose to imitate practices they observed and follow the field rules, instead of violating them or inventing new practices. Even though Karen described the men in senior positions in the mixed-gender networks pejoratively, as ‘dinosaurs’, she acknowledged their expertise: ‘There are dinosaurs (men) … and yet the dinosaurs have a lot to offer in experience …if only they would open up and offer that experience … I think it’s a huge opportunity’. Gaining insights from such men can help women increase their own field positions: “Because a man is taken more seriously and it depends a little bit on the powers that be, whether you are given the same credibility or not (Denise). As such, mixed-gender networks offer the space not only to facilitate enculturation into the field where women can learn the culture, values and rules of the game in addition to the identities of those individuals and groups considered the dominant players.

Discussion

Entrepreneurship as a gendered field

The starting point for our analysis has been the recognition of the gendering of entrepreneurship and the underrepresentation of women as credible entrepreneurs, partly due to their lack of understanding of entrepreneurial norms and practices. We have shown that the marginal positions women occupy in informal social networks compromises their relative lack of perceived legitimacy as entrepreneurs and has stimulated the formation of women-only entrepreneurial networks. Our findings confirm the central role of the entrepreneur in creating, maintaining and developing the field. Many of our respondents understood that this required the ability to gain a thorough understanding of the rules of the game (Carter and Spence Citation2014; Harrison, Leitch, and McAdam Citation2020), which represents the legitimation of entrepreneurs and their participation in the field: as players they know the right action to take in any given situation.

In order to explore the implications of this, we have employed Bourdieu’s theory of embodied practice to provide insights about how women manoeuvred in the field according to its doxa and their habitus in their pursuit of capital accumulation. Specifically, we have followed feminist applications of Bourdieu which see habitus as core, and gendered habitus as relationally constituted and socially differentiated from the opposite gender. Habitus, therefore, assumes an innate complacency that shapes gender expectations, and hence one’s legitimated position in the field, according to concrete indices of the accessible and inaccessible, of what it is and is not for us (Bourdieu Citation2001). As such, habitus must always be seen in context and in the light of institutions, history and social order. For Krais (Citation2006) the gender order is entrenched as masculine domination is legitimated. However, there is scope for reflexivity in that one can change one’s illusio and define and improve our position (Grenfell Citation2014a), as we think about and act in the world, interpret it and attempt to order it via classifications, myths, ideologies (that is, our symbolic orders) and storytelling. These are linked to our social practice and can potentially dislodge doxic attitudes and encourage social change (Krais Citation2006, 131). Illusio reflects the way in which field conditions make for the emergence of particular interests. However, individual social practice is never determined according to specific rules but, as our participants recognize, is endlessly and variously negotiated according to personal circumstances: it is, in other words, represented and evidenced in regularities and trends and not in rules.

On the basis of our findings, this has four implications for the contribution our analysis makes to entrepreneurship: for our understanding of the interrelationships between habitus, doxa and field; for the development of the Bourdieusian concept of gender capital as part of the habitus; for our understanding of the gendered doxic order as a system of presuppositions that shape actions in social fields (Benson and Neveu Citation2005), which are shared by the dominated and the dominant as hegemonic images of binary opposites, which in turn inform the taken-for-granted stereotypes of how women and men perceive themselves and are perceived (Huppatz Citation2014) and for our understanding of the basis for sustainable and impactful policy intervention to overcome the structural barriers to women’s participation in entrepreneurship. In this discussion, it must be remembered that there is no simple homogeneity here: women’s experiences are contradictory and heterogeneous, and in practice there are exemplars of ‘subordination to domination’, examples of exerting agency and examples of conflict. On the basis of our analysis, we demonstrate that formal women-only networks, established as part of an economic development strategy, actually perpetuate and reproduce the embedded masculinity of the entrepreneurship domain.

Bourdieusian analysis in entrepreneurship

Our analysis differs from other entrepreneurial appropriations of Bourdieu to date in specifying the relationship between field, doxa and habitus instead of that between habitus, capital and field. The challenge for the women in our sample was three-fold. First, for them the established order is reproduced and reinforced so that the ‘socially arbitrary nature of power relations (e.g. classifications, values, categories, etc.)’, which initially produced the doxa continue to be misrecognized (Deer Citation2014, 116). Second, as the comments of our participants, in both women-only and mixed-gender networks make clear, their justification of this established order informs and conditions their internalized sense of limits, their sense of reality and their aspirations. Third, the taken-for-granted assumptions that constitute doxa are powerful and appear to be the field’s foundation stone, in that they determine the stability of the objective structures as they are produced and reproduced through the women’s practices and perceptions. In essence, the presuppositions embedded in the doxa guide the appropriate feel for the game (Bourdieu and Wacquant Citation1992). Our findings suggest that even interventions, such as the creation of women-only entrepreneurial networks, aimed at overcoming the masculine bias endemic in advanced capitalist systems, appear to do little to address it.

From a Bourdieusian perspective this is not surprising. He argues, for example, that the greater its autonomy and distinctiveness the more the field is produced by and produces agents who master and possess an area of specific competence (say, entrepreneurship). The more the field functions in accordance with the interests inherent in the type of activity that characterizes it, the greater the separation from the laity (Bourdieu Citation2000) and the more specific become the capital, the competences and the ‘sense of the game’. This closure is an index of the autonomy of the field. … As the field closes in on itself, the practical mastery of the specific heritage of its history, objectified and celebrated in past works by the guardians of legitimate knowledge, is also autonomized and increasingly constitutes a minimum entry tariff that every new entrant must pay. The autonomization of a domain of activity generates the doxa, an illusio that forms the prereflexive belief of the agents of the field, i.e. a set of presuppositions that implies adherence to a domain of activity and implicitly defines the conditions of membership (Hilgers and Mangez Citation2014). In so doing, the barriers to entry to the field (faced, for example by women seeking to become entrepreneurs) become higher, and whatever the combatants on the ground may battle over, no one questions whether the battles in question are meaningful. The considerable investments in the game guarantee its continued existence. Illusio is thus never questioned (Heidegren and Lundberg Citation2010).

Gender capital in entrepreneurship

As our analysis demonstrates, the identification of gender capital specifically has important implications for women’s networking. In general, women have less social capital than men and face problems in accumulating it, not least because of credibility issues in networks that prevent them from playing the game (Burt Citation1998; Eagly and Carli Citation2007; Palgi and Moore Citation2004). Specifically, our research suggests that women who join women-only networks do so in an attempt to counteract this masculinity, for example, by talking to other women and reducing isolation. However, women joining mixed networks did so because these networks were considered to offer more opportunities to be more strategic and competitive. In Bourdieu’s terms, these women acknowledged the field dynamics and referred to men as ‘jockeying for position’. Nevertheless, they still became members in order to ‘think like men’, to increase their field positions and thus credibility. Indeed, the respondents were very aware of who the key players in the field were and were also well aware that the rules were normative, masculine and traditional. Even though the women wanted to learn the rules, they never challenged or questioned the taken-for-granted assumptions on which they were based. Thus, entry into mixed networks specifically was seen as a way to learn the rules of the game from the more established players in the field. Our evidence suggests that women imitate practices they see in the networks, especially in the mixed-gender networks, which allows them to follow the field’s rules closely in order for them to be what they deem to be successful. The extent to which this is likely to be successful is moot, on the basis of the Bourdieusian analysis above. Indeed, the asymmetrical value of femininity and masculinity in entrepreneurship results from the reproduction of two different forms of capital grounded in global neoliberalisation processes (Marttila Citation2013) and a wider cultural grammar of the inferior status of women and femininity: men’s investment strategies in assertive masculinity which sets the rules of the game in the field is itself a form of gender capital that allows them to negotiate their status in entrepreneurship and in society at large (Matos Citation2018).

Doxa and the perpetuation of masculinist entrepreneurship

For Bourdieu, as we have shown above, it is through illusio that players bring their habitus to the field and engage with the practices that constitute it. The stakes that inspire this engagement are the objects of value in the field, including values and beliefs, and illusio represents the more conscious counterpart of the tacit and unquestionable doxa of a field. That said, however, illusio is not always wholeheartedly invested by all players, and it is important to recognize the potential weakness of illusio for those (such as many of our women entrepreneurs) who sense they are somehow out of kilter with the objects of value that are at stake within the field (Colley and Frédérique Citation2015). This suggests that future analyses of the field of entrepreneurship and its mechanisms and conditions could usefully go beyond existing discussions of illusio (Meliou and Ozbilgin Citation2023) to examine different types of illusio and their implications (Colley and Frédérique Citation2015): this would differentiate congruent illusio (buying into the ‘official’ stakes of the field); weak illusio (doing things their own way); and conflict illusio (power games arising from conflict with established players). Such research could also usefully examine the implications of the disappearing grounds for illusio as shifts in values arise from ‘cross-field effects’ (Rawolle Citation2005) from, for example, shifts in the global economy, politics and the media.

What our analysis has demonstrated is that, for women entrepreneurs, negotiating access to, acceptance in and legitimation through the field of entrepreneurship is in many respects an illustration of what Bourdieu (Citation1998) has referred to as toxic illusio, the allure of a game that draws participants in whilst at the same time preventing them from developing a healthy distance and critical perspective about the consequences of the game for its various stakeholders and participants. There is no such thing, in other words, as a disinterested act. Across the life course socio-psychological transformation occurs through a whole series of imperceptible transactions at the borders between the tacit (projection, identification, compromise, sublimation) and the conscious. Because of affinities and disaffinities, social actors gravitate to social locales which most share the values and interests of their own social provenance, views and practices – it is not so much that individuals occupy specific social fields, but they are occupied by them.

For Bourdieu, social actors are preoccupied by dispositions which orientate thoughts, actions and choices – illusio is to see ends without posing them; a future which is quasi-present because it acts there; a game which is so good that it forgets that it is a game, embedded in a totality – the dominant gender order (Connell Citation1987) – which is not reducible to the field. Social agents, both female and male, draw on this totality for resources to pursue their own projects of value, the realization of which requires a point of comparison or ‘imagined audience’ (Graeber Citation2001, 87). In the case of entrepreneurial networks, this audience – the gender regime consistent with a dominant gender order – acts as an ‘unequal system of value that both enables (men) and constrains (women), thereby conferring power to one … while restricting the freedom of another’ (Matos Citation2018, 11). Stated aims and objectives are therefore never as they appear but are instead the epiphenomena of interest. Such interest is doxic in that it corresponds (or not) to a particular orthodoxy and is expressed through habitus because of the immanent structure that constitutes it in ontological relationship with field surroundings. Life trajectory is never only a conscious plan but the response to what life throws up – illusio is knowledge born from within the field – ‘it is in my skin. I am caught: I did not choose that game I play; at the same time, I am not the subject of my actions. … . I do not have to act to dominate or subjugate another. It is sufficient for me to express the interests of my social provenance … in order for symbolic violence to occur, because they will privilege one view of the world over another and I have no choice but to represent my own’ (Grenfell Citation2014a, 164).

From analysis to policy