Abstract

In this edited interview, feminist visual artist Joanne Leonard contemplates her works of art as interruptions of linear chronology that reform temporality to reflect more accurately the intersection of memories. The interview, conducted by Sidonie Smith, further explores the duality and relationality present in Leonard's photography, photo collages, and visual-verbal works, as well as in her autobiographical book Being in Pictures: An Intimate Photo Memoir.

On December 10, 2010, Sidonie Smith interviewed visual artist Joanne Leonard at the University of Michigan's “Author's Forum.”Footnote1 This interview focused on Leonard's visual-verbal auto|biographical narrative Being in Pictures: An Intimate Photo Memoir (2008), a narrative in which “the art practitioner [acts] as multilingual guide through the life story of a feminist artist” (Smith).

We are very pleased to publish the edited transcript of this interview as the second installment of our new segment, “The Process.” This reoccurring section of the journal is intended to provide a space for initiators of life narratives to voice their unique perspectives on the construction and|or collection of said narratives. By situating scholars in this vantage point—behind the narratives that we engage with—it is our intention to expand productively the discourse in our field by calling attention to the multiple and varied ways in which interpretations of the self are fashioned, narrated, and mediated.

This interview with Leonard meets the objectives of “The Process” by clarifying aspects of the artist's methods, both in constructing Being in Pictures and in her work as a visual artist. While Leonard does touch on her process of art-making in this interview (and even more so in her book), the real gift of this interview is the insight it offers into her thought processes behind the art-making. It is this insightfulness and self-reflexivity, brought out by Smith's careful questioning,Footnote2 that Leonard brings to the interview and that add intangible layers of meaning behind the tactile layers of her collages.

Leonard, for example, presents the argument that photography captures only what is present and is unable to record successfully that which is absent. She articulates that her photo collages are better able to represent what is absent, as she is able to supersede time by allowing memories to step out of chronological synchronization and meet and merge with other times in a way that is not possible in unaltered photographs. Interestingly, Leonard draws a connection between feminism and photography, as she states that: “Feminism is a tool for looking at what's missing.”

This intertwining of feminism and photography speaks to the duality of both Leonard's artwork and her book. In her foreword to Being in Pictures, Lucy Lippard writes: “Continually resurfacing throughout this book is the notion of doubling and bonding, connections and separations…as collage…comes to the rescue, reconnecting fragments. The power of these images lies not merely in personal honesty and expressive talent but in the artist's clear-eyed acknowledgement of multiple truths.” In her introductory remarks that preceded the interview, Smith also recognizes the role duality plays in Leonard's work. She states that Leonard's work “crosses media—a set of words talking to and about sets of images, but also each telling different stories, drifting to different effect and affect” (Smith).

This theme of relationality emerges throughout the interview, the book, and the essays collected in this special issue, as they ask readers to consider self to other, word to image, art to viewer, and writing to reader, among other relationalities. In Being in Pictures, Leonard asks: “Where does a mother's story end and a daughter's begin? That might be…the central question of this book, the point of the autobiographical approach I’ve taken in putting this book together—to discover the lives in my own images, to remember the stories of my mother, to give the stories to my daughter, and to anyone else for whom these ideas and themes resonate” (240). This navigation of self and other is present in the interview and resultant transcript as a discourse between Leonard and Smith that deepens the artist's understanding of herself and her work, as much as it functions as a means to extend the audience's understanding of the artist. This dialogue is further expanded through the inclusion of the audience as both witnesses and participants.

In reference to the essays collected in this special issue, Paul Longley Arthur articulates that they “resist categorization,” “reject and forbid closure,” and “elude framing” (4). This rejection of categorization is also a fair assessment of Leonard's visual-verbal photo collages. Furthermore, as Maria Tamboukou theorizes: “Leonard, as the autobiographical subject of the analysis, [is] far from being essentialized, pinned down in a fixed subject position, or encased within the constraints and limitations of her story” (29). The relationship between the multimodal artworks studied in this special issue, which “elude framing,” can be read as an appropriate representation of a self that cannot be “pinned down in a fixed subject position”—a correlation that seems ripe for further inquiry.

While the exploration of intent in this interview makes a significant contribution to “The Process,” it is particularly apropos that this piece appears in the special illustrated issue of a|b: Auto|Biography Studies, Framing Lives. By situating it in this special issue, the interview is placed in direct conversation with Maria Tamboukou's essay on Leonard's auto|biographical artworks, “Narrative Personae and Visual Signs: Reading Leonard's Intimate Photo Memoir,” and my own essay exploring Judy Chicago's feminist visual lexicon, “When Words Are Not Enough: Narrating Power and Femininity through the Visual Language of Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party.” All of the essays in this special issue, however, make palpable connections to this interview, in that they seek to extend readers’ ability to make meaning of visual narrative, and to incite more complex readings of the interplay between the visual and the verbal.

Leonard explains in the text of her book that she has “created a lexicon of imagery that [she] bring[s] along from piece to piece” and “worked increasingly to find a visual vocabulary that describes female worlds, female lives” (Being 222, 186). The work that this special issue seeks to accomplish, then, is a consideration of the means by which scholars studying visual lexicons can better access, navigate, engage with, and “read” visual and visual-verbal life narratives. Each of the essays presented here explores auto|biographical means of utilizing visual rhetorics to extend narrative: Lee-Von Kim offers a theoretical foundation from which to explore “making lives and selves visible” (103); Jessica Wells Cantiello explores the complex role that photographs play in educators’ memoirs of teaching Native American children; Cynthia Huff considers the illustrations in “animalographies;” and Elisabeth El Refaie articulates graphic narratives’ ability to reshape cultural discourse. Read in conversation with these essays, the following interview makes a substantial contribution to the work of this special issue.

Sidonie Smith: I’ve asked Joanne to give everyone a sense of how she went about creating Being in Pictures and some of the questions that [she] had to address as [she] was assembling it.

Joanne Leonard: I thought of two ways to—or many ways to—answer this question, but I’m going to try to just do it in two ways. The first was having to pick the photographs. Imagine eight four-drawer filing cabinets, hundreds and hundreds of pictures; those are the ones I had printed and then all the negatives that hadn't been printed yet, and what was going to go into the book? I put up about 300 prints in my studio and what LeannFootnote3 came to call my posse and I came [together] and chimed in on what they thought was most effective. We thought about the organization, what photographs meant something together, and we went from there. I went away with small scans of all of these and I began to work out just what text might be on the pages with those images, with no particular order for these texts that I was creating. It was later that we wrestled it into some kind of form and, well, that it became more chronological.

The other aspect of how the book took shape and what questions I was asking as they put the book together is—and I’m really only questioning it now—why it seemed so inevitable that this book would be autobiographic. That even though my photographs were of poverty and protest in West Oakland, California, the Olympics,Footnote4 and things like that, that almost everything I did seemed in some way to be a recording of what I had done and felt and seen. And, lest that seem too thoughtless, I’m going to try to make it make sense—to bring you into how that theme seemed so inevitable to me.

First of all, I’m a twin, and we’ll talk about this a little bit more in a different way later on. But that means that I always could look out and see myself in a certain way. Sort of imagine how it looked as a picture, and I think that had an effect. Also, I’m the daughter of a psychoanalyst, so the thought of stories—I mean the stories of one's own internal life—this had meaning and was important through my family. These inner-life stories were almost like gifts to my mother. She appreciated it if we would talk about how we felt about things, so it was very important in my growing up.

I’ve only recently thought of the fact that when I was twelve, Anne Frank's Diary was published in the United States.Footnote5 Anne Frank's Diary, for all the horror it conveyed, also said that a young girl's thoughts, and life, and everyday events could be important. I think maybe I’ve carried that notion of a story inside me and a relationship to her in ways that I have only begun to think about.

And lastly, there's Hollywood,Footnote6 the idea that you could be in a film, and the intersection between psychoanalysis and screen memory and all those kinds of things.

Smith: I wonder if you could talk a little bit about how you see your feminist vision and the process of putting together Being in Pictures.

Leonard: For me, feminism is something like a filter. So that makes it a little bit photographic in a sense—something to look at the world through and something more than just incidental, but vital. Some of you know that when heart attacks were studied and statistics compiled by the medical profession, for years it was in terms of symptoms that only happened to men and not what the symptoms were for women. [This shows that] it can be lifesaving to think questions through in terms of women. I really feel that having [an understanding of] the way women's lives actually intersect with the world at large is crucial. So, in that sense, I thought of it as feminism|feminist.

In addition, in terms of an artistic process, and in terms of career advancement, for example, and consideration of tenure,Footnote7 there's a model of an artist at large in the world that would suggest that a person isn't serious if the work doesn't flow continually. If there are large portions of a person's time spent, as one of my friend's has done, supporting her husband before taking on her own career. Having a late start, a discontinuity, stopping because of children, or less time for work, all of those things can make an artist or a writer or any kind of artist seem not serious and not to be counted.

So, in the sense of giving an account of a life that happened and some wonderful surprises, like being included eventually in Janson's History of Art, when a book like that had been published for 20 years without the work of a single woman, and most of us (my generation) didn't even notice when we were in college and [couldn't see] what was missing. Feminism is a tool for looking at what's missing. And that's what I thought of in terms of making my book.

Smith: When you return to reading Being in Pictures now, how do you think about the readers of Being in Pictures and the kind of narrative you were composing for them? As you were putting it together, were you thinking about your generation of women artists or “this gives me an occasion to speak to younger artists”?

Leonard: [Reading] “It's not easy for anyone to mark the moment of realization: ‘Now! I’ve become an artist’” [(Being 6)]. So, in a sense, I’m telling the story of how a woman would become an artist. Not the genius with the muse on his shoulders, but a different story there. Especially in a case like mine. I never majored in art or got a degree in it. Becoming an artist might seem to have happened by accident. [Reading] “A colleague at the University of Michigan once told me that it wasn't for him (or me) to say whether either of us was an artist—that the definition|designation of who was an artist comes from outside oneself, from the recognition by art historians, critics, and the like. I thought that's all very well for him to say; men are expected to dedicate themselves to vocations and avocations, but even as a young woman, I had to take myself seriously as an artist in order to allow myself the time, money, and space for my art. In fact, looking back, I think it was that very ‘allowing’ more than anything else that defined me as an artist; I built a darkroom when I could have fixed up a kitchen” [(Being 6)].

Smith: Now you noted, of course, how important the process of twinning is, and twin-ness, and twin identity or “twin-dentity.” I wonder if you could talk about how you see the effect of being a twin, of thinking about twin-ness. Thinking about twin-ness in terms of the composing of the book and what people might see as they’re reading—about the thematic, the esthetic, and the knowledge of twin-ness.

Leonard: Twins come up more here and there throughout the book. I say at the beginning that every page is about me, but Elly (my twin sister) is also on every page. On the end papers of the book, [there is] a picture of me [with my camera, which is repeated], that the designers and I used…to suggest a doubling: both the camera looking in and the camera looking out, but they are repeated, repeated and twinned. There's also the notion of relationality that is, maybe again, the motive for the book.

Jean Baker Miller wrote a book about psychology, Toward a New Psychology for Women, and [in it] she posits that a male model of maturity is getting to the top of the mountain where [the individual] can stand alone [emphasizing competition and power]. In Jean Baker Miller's version, the mountain is inverted so that as [the individual] builds friendships and relationships, and that's what a mature person in a society that might be defined by a different kind of relational model would be: a person where relations are paramount, and higher than singularity or “independence.” And so I think my twinship is an influence on the value I place on relationships.

Smith: Another kind of situation in your life—before working on Being in Pictures—had to do with your mother and her struggle with Alzheimer's, which was very important to you both as a daughter but as an artist as well, trying to figure out how to watch someone who, in a sense, is losing memory. And for you as an artist who is working with visualizing memory, that must have been profoundly sad, of course, but also a challenge. I wonder if you could talk a little bit about that, about…that aspect of being a daughter, of being a daughter who is an artist, of thinking about or watching somebody who's slipping into memorylessness.

Leonard: The absence of something is pretty difficult to photograph. The photographs depend on presence. So to create a way [to do this was very important to me]. There have been many things that have inspired me to use collage with my photographs, but certainly this was one of those things. There's this saying, “A photograph is worth a thousand words”—but the truth is, photographs don't explain anything. So you really don't have the story. You see an older woman on a bench. You know nothing about what happened before and so on. So to find a way to layer some of these stories, that's what I was looking for. And that was quite a search. And that's why that part of the book is very important to me. I had picked out—some of the things that I’m reading now are just little bits from the text in the book: “Exploring issues like female identity and biography, and visually representing memories, became urgent quests as my mother declined from Alzheimer's disease. I struggled to represent her lapses while attempting to suggest, in pieces combining text and images, stories she could no longer remember. Absence and loss are all but unrepresentable through traditional photography since photography inherently depends on presence, a presence recorded by the camera. The collage series that evolved is the one I called, Not Losing Her Memory: Stories in Photographs, Words and Collages” [(Being 190)] .

Smith: That's so interesting in a way, because your project then becomes retrieving your mother's memories, remembering for her. There are some very interesting works out there where daughters are trying to experiment with different forms to recover the stories of the mother and to position themselves as the mother. I’m thinking of something like Jamaica Kincaid's The Autobiography of My Mother, which itself poses this very interesting, strange genre. This would be to think of your work as embedded in a set of texts by women who are remembering and remembering as someone else and remembering as their mother at the same time.Footnote8 It's very interesting.

Leonard: I wrote this at the very beginning of the book and I think it also goes to what we’re talking about right now: [reading] “Toward the end of my mother's life her memory began to fail. My sister took her to doctors for possible diagnosis. A neurologist's report begins with a humorously incongruous list of female family traits: ‘There is a family history of allergies, twinning, prematurely gray hair, uterine fibroids…and artistic talent.’ I can't think of a better way to suggest the dual nature of this book: as personal as medical histories yet with a public in mind of those who might be both intrigued and captured, as I am, by the prospect of exploring women's lives through pictures and stories” [(Being 3)].

Smith: Another part of the book, which falls right in the center of it, it's almost like the centerfold area, is the story of your miscarriage and the work that you did in the wake of that. I wonder if you could talk about what it was like to return to that moment and then what the response to your work was at the time you produced it.

Leonard: My editor might agree with me that the conversation about my [creating] a book started years ago with the question of possibly reproducing this work [Journal of a Miscarriage], which was made in 1973, but which simply couldn't be published at the time.Footnote9 It's not just the story of the miscarriage, but the feelings afterwards of sexuality and anger, desire, and a desire for pregnancy. The images are considered difficult and so it was the courage, really, of Leann Fields to think about publishing this book and surround it with the rest of the life.Footnote10 But it was work that met at various times with people slamming doors, even though I was very encouraged and I showed the work in 1973 and had some very excited responses. The making of the work, as miserable as I was (and it was a miserable time for me), was also a time of great excitement because I was doing something I had actually never seen before. I was finding ways to represent something I had no idea how to do.

That might seem strange to this audience who knows very well the work of Frida Kahlo and how there are images, not a lot, even now, of women's reproductive lives, but Kahlo's work of her own miscarriage is well known today. But if you think back to 1973, it's just about then and just a little later that her work became known to me at all. So I was without any model of this, but with some sense from the beginning of the women's art movement, that women's lives, in this intimate kind of detail was beginning to be a more commonplace subject. So it's quite amazing that something so normal, in a sense, as pregnancy-loss would be so absent from our visual making of images of something that we already know, but which simply didn't exist in visual art. But people were quite disgusted at times and didn't want to see it, and so it's very exciting that in this book there are over 30 images [from Journal of a Miscarriage].

Smith: So another thing that [the book] provided was an occasion to, in a way, publish formerly unpublishable projects and yet to do it in the context of another kind of project, which was a life writing project. One of the themes that runs through Being in Pictures, or one of the explorations that it undertakes, is a kind of engagement with multiple identities, but particularly the identity of mother and artist, especially the conflicts around those roles, the productive—and there's a productive side to that conflict, but also the kind of ongoing haunting of that conflict. I wonder if you might talk about how you see yourself in Being in Pictures negotiating that conflict or about how that conflict defined how you understood yourself as an artist.

Leonard: I’ll try [to answer that] partly with this passage that I picked out from the book, “The story of this work's creation” [(Being 152)], and I’m talking now about Julia and the Window of Vulnerability (1983),Footnote11 the piece I made in response to the fears of the missile crisis: [reading] “The story of this work's creation offers an alternative story to the big ‘ah ha’ moments with light-bulbs going off over the creators’ heads that are the common stuff of artists’ biographies. ‘How's your work going?’ people would ask and I sometimes wanted to shout, ‘When do you suppose I get a chance to do it?’ But I didn't say anything except, ‘fine.’ The summers, after the school term had ended, held more opportunities for art making, but I felt tense about competing needs and desires: I wanted to spend time with [my daughter] Julia, but also to concentrate on my artwork, and to teach a summer course for added income.… That summer I made Julia and the Window of Vulnerability; what I called my ‘studio’ was a small, crowded bedroom that housed eight four-drawer filing cabinets full of negatives, prints and papers. A small table and chair that I’d bought at a local resale shop took up every inch of the remaining space. I remember sitting and working out the details of Julia and the Window of Vulnerability pieces at that table. There were four variations when I finished. I worked with great intensity and remember how important it was to me to suggest something of my great anxieties about the world and Julia's safety, particularly in the political climate at that time the nuclear arms race” [(Being 154)].

“To make Julia and the Window of Vulnerability, I used a color negative and printed it on a black-and-white photo paper” [(Being 156)]. I’m not going to continue with the details…about how I [physically] made things, but it was another idea that we had about the book that there would be curiosity about some of these things; especially as they seem so antique now since they are not Photoshop. But you look at a printed page and you really don't know that a collage was made by figuring out some way to do it in the darkroom and built on that with paste and glue (and other methods) after the darkroom.

Smith: So that's another way in which Being in Pictures becomes a kind of archive of art-making.

Leonard: Yes, it's kind of a history of an evolution of how this idea came from here and built on that and went on from there.

Smith: Autobiographical writing and self-portraiture, whether it's in multi-media or in words or in images, is always a relational genre. We come to know ourselves through our inter-subjective engagements with other people, sometimes imagined, sometimes real. But those others are often living, breathing human beings who have their own response in [the] reading of a book. I wonder if you could talk about the aspect of composing and publishing Being in Pictures, which is an intimate portrait of nested families, particularly your daughter, whose voice is incorporated as another interpreter of your work.

Leonard: I do include something my daughter wrote about one of the photographs of herself, but she did not take—want—a big part in making decisions about this book.Footnote12 She put a few photographs aside, “Mom, not that one.” And I respected that. But she did not concern herself a lot with what I would say, only in a few instances.

One of the most serious concerns [in constructing this book] was in how mortified my mother would have been by her own condition and so I wrote this about a photograph of her that shows her quite compromised from Alzheimer's: [reading] “The making public of something that was never meant to be placed into the public realm is a form of ‘outing,’ a struggle for control over personal histories. When confronted with a confused, elderly person, my mother had often said, ‘Shoot me if I ever get like that.’ While I believe she would have applauded the politics behind my desire to give the nearly unthinkable subject of dementia a form and forum for public dialogue, she would have been personally mortified by being exposed as a demented person. Clearly there are tensions between what I might ‘expose’ as a photographer and my mother's feelings, feelings that, as a good daughter, I would honor. I also face this dilemma from another direction: when I write or make art about my life with my daughter, I risk exposing things she might prefer not to have made public” [(Being 200)].

Valerie Traub: I want to follow up on the relationship between your visual artistry and your narrative artistry in the book, and the connection between them, because it seems really clear that they’re intimately connected. Did you ever think about not making the narrative of the book autobiographical? That is, did you consider a different kind of form for what you wanted to say about the pictures?

Leonard: I had to consider it. I went to the American Academy in Rome and was writing, and Francine Prose and a poet colleague of hers came to my studio and they both said, “Lose the text…. Great images, [but] lose the text.” I had hardly even written anything, but they saw a little bit of autobiographic writing. I never wrote without thinking about pictures, and I learned just enough of a program called InDesign to always be writing on a page that I kind of designed opposite the images. So of course the photographs were very important to me—at the heart of what I was writing—and I was taken aback, offended, defensive, but today, I mean, in the preparation for this conversation, thinking about it and what form the book would take, I had to honestly say to myself, it never really seemed possible to lose the writing or to lose the autobiographic slant. I did for a while try to organize the book a bit against the autobiographic: by topics and not chronologically, with topics like “professional life” or “motherhood.” I started out today saying, “Even when it was about West Oakland, even when it was about the Olympics, I felt myself to be in some kind of position as the autobiographic subject.” I’ve never been a journal keeper, so I think the photographing itself was an act of keeping track, of keeping a record, of keeping autobiographic notes, and that's how it came to seem so logical that the book too would have an autobiographic cast.

And I had a lot of help. I had LeAnn's editing and Peg Lourie's editing. Abby Stewart (a psychologist) read this. My twin sister read it. So I had many readers who said, “My, I don't get where you’re going with this,” and so on. Probably lots of projects of writing are like that, but my writing has been a collective effort to a certain extent, too.

Audience: To me, the photo collage seems a more narrative genre than a photograph. What I have been thinking about is whether the collage element is the connection because of the ability to further narrate?Footnote13

Leonard: In a way, making collages could be considered a kind of textualizing of the work. I think that because every photograph is an extraction, it's really something very bare and bereft of its context. I said that photographs can't really explain anything. When you see a picture of a war, you really don't know if it's a just war. You can know that war is horrible. You can know somebody's winning, but you can't know why or the money behind it or anything. The photographs don't tell those stories. The very kinds of resemblances and coincidences and parallels and metaphors that something may have in it [are not always apparent]. If I want to say, “Pay attention to this,” by bringing a collage to the surface and thereby saying, “This is like that,” this is what a collage does.

I have had conversations about dichotomies and how problematic these are, not fantasy and fiction or personal versus political, but something more complex. I can do that and maybe make it evident that I’m not entirely simply dividing the world into dark and light or inside and outside and things like that, but create a more nuanced secondary text or layering of one thing on another, or a restoration of the original context or some other context that now seems important to this image.

Audience: I was really struck by the way that you talked about documenting absences and that the camera relies often on the documenting of presence. Then you spoke about the nearly unthinkableness of dementia and the unspeakableness of miscarriage and the politics of feminism as documenting what's missing. It made me think about your process when you were going about capturing some of these things, and did you have a conscious awareness of capturing something that is often absent or invisible, or did it only come as a sort of post-hope sense that you captured something that one doesn't usually see?

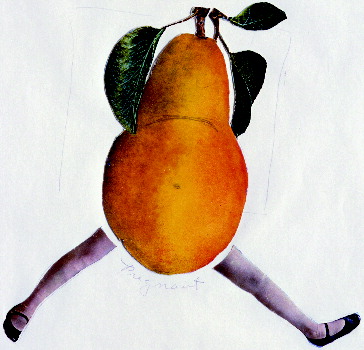

Leonard: Probably a little of both. [I had] the impulse to put blood from the miscarriage right on the pages while it was happening. I started out to make my journal about being thrilled to be pregnant, but it was already very complex. I wasn't married (see ). I didn't know how I was going to support myself and those doubts even seemed to be part of the picture. And [then the questioning], “did I cause [the miscarriage]?” and all of that, so the going ahead with [the blood on the page]—it's as close as I get to kind of replicating the myth of the inspired artist and the inevitability I had to make art out of it, and so on. But that piece [of Journal of a Miscarriage] had that kind of intensity and necessity within it.

Then a lot of it has also come afterwards, even in dealing with the reception of the piece, where it wouldn't be the unspeakableness of it or the [question] who would ever want to see this or “we all know about that, don't we,” which was what John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art said in a very patronizing tone after paging very carefully through the images without response.Footnote14 Implicitly, he seemed to be adding, “and why would you want me to have to look at it?” It was quite devastating in ways I can't completely capture. I actually didn't show the piece to anybody again for 20 years. I figured if somebody's going to see [the work], it's not going to be because of me. I’m not going to stand there in front of people and put this forward. That's been a complication throughout. It's a better, safer, happier place for it in a book than for me to be present as the maker of that and my body and my blood and so on.

Audience: I’d like to follow up on this question which seems to be teasing people—this business of collage and writing in the digital era. In your work, you have all these separate images and there's something really very physical about collage because you’ve got these separate images that you’re bringing together. The writing seems to be making it all flow together. It's almost like weaving it together and you have a pattern from different things. I was wondering how different does it make your process now that technology is digital?Footnote15

Leonard: This is such a good point because almost every way that the work can come into a public connection is a remove from the physical layering and so on [of collage], which was very important to me. Most of my collage work was made before Photoshop, and people often ask, “Don't you want to re-photograph this and then have the re-photographed collage be a more seamless version of [the] paper and glue original?” And I said, “No, no, I like the evidence of the rips and the tears, etc.” I didn't want unwell-done gluing or bubbly surfaces or something, but I wanted some residue of the multiple layers.Footnote16

Smith: It's very interesting to think about how one [might] think about teaching Joanne's book, interesting [to think] about a kind of course that one could put Joanne's book in and something that would look at the textual [verbal-]visual intersection and women's forms of self-presentation, self-performance, [and] self-representation. Perhaps starting with somebody like Charlotte Salomon and working with her text, and then going to yours and then Phoebe Gloeckner. [The course could continue with] Alison Bechdel and move to Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi. It would be a very interesting course to put together, to assemble, and, in that course, to work with students and have them think about what's going on in the visuality of the text, what's going on in the narrative or the language-based part of the text, how they’re working together or how they’re moving in different ways, how they’re telling different kinds of stories and how those stories relate to one another.

Leonard: I would love that.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Joanne Leonard and Sidonie Smith for making the transcript of this interview available to us.

Notes

1. Before the interview, the 9-minute film Joanne Leonard: A Life in Pictures was shown to the interview audience. The film may be viewed at: <http://playgallery.org|video|joanne_leonard_a_life_in_pictures/>.

2. At the end of the formal interview between Leonard and Smith, audience members were invited to participate by asking Leonard additional questions.

3. Leann Fields is Chief Executive Editor at the University of Michigan Press.

4. In 1972, Leonard “was invited to fly to Japan to be one of two official photographers to the U.S. Olympic team” (Leonard, Being 87). This assignment contributed to her sense of professionalism and caused her to feel “suddenly deemed worthy in a profession [she’d] not fully recognized as [her] own” (89).

5. Due to religious persecution both prior to their immigration to the US and in their new land, Leonard explains that her family “quickly put aside anything that might mark them as overtly Jewish” (Being 14). The Diary then takes on added importance for her, as she explains that she and her sisters “knew remarkably little about World War II beyond what we learned from the story of Anne Frank” (18).

6. Leonard “began ‘being in pictures’ as an infant in front of the camera” (Being 8). She and her twin sister both played the role of one infant in the 1942 Hollywood film The Lady Is Willing, starring Marlene Dietrich.

7. At one time, Leonard co-taught a course at the University of Michigan called “Photography, Ethnography, and Autobiography.” Her “colleague, a social scientist, received recognition from her college for her innovative cross-disciplinary teaching” (Leonard, Being 174). Leonard “received the lowest evaluation and merit salary increase of [her] teaching history” (174). When she queried the Dean, she was told that the course “appeared to be one largely responding to self-interest,” as it was a “women's class” (174).

8. With regard to her collage Conversation: My Mother and Her Mother (1991), Leonard writes that the piece “has my mother talking to her mother, but their ages are reversed; in this composite image [my] mother is older than her own mother and tells two memories of her mother. For the text I used two contradictory stories Mom had written at different moments, long ago. Visually, by allowing the two texts to interrupt and cancel each other, I am suggesting how memories frequently refuse to coalesce into one coherent narrative” (Being 199).

9. “It might be difficult for a contemporary reader,” Leonard explains, “to appreciate how unusual it was at this time to make or find acceptance for art about an intensely personal subject like miscarriage. Artistic precedents that existed were largely unknown or rarely seen by artists of my generation” (Being 113).

10. A photography curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City “thrust the work back in its box with evident disgust” after viewing it (Leonard, Being 114).

11. Julia and the Window of Vulnerability (1983) “was reproduced in full color in Gardner's Art through the Ages (1991),” (Leonard 152) representing quite a milestone not only for Leonard, but also for feminist art and artists.

12. About her mother's photograph Julia, One Week Old (1975), Julia wrote: “This photo has always felt so loving and warm as though you see this baby through eyes of someone who loves and knows this baby like a ‘view’ as opposed to just a snapshot or a family photo… I feel that this and all other photos of me before I could remember help me remember being a baby” (Leonard, Being 145).

13. I have edited this question significantly in order to represent more fully what the speaker was asking Ms. Leonard.

14. John Szarkowski was Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City from 1962 to 1991. His dismissal of Leonard's work—from his position as a prominent curator, critic, art historian, and photographer—was both a significant personal rejection and a professional slight spanning almost three decades. Interestingly, Szarkowski's retirement coincided with the 1991 publication of Gardner's Art through the Ages, which featured a full-page full-color reproduction of Julia and the Window of Vulnerability.

15. I have edited this question significantly in order to represent more fully what the speaker was asking Ms. Leonard.

16. In Being in Pictures, Leonard further explores the question of writing in her multimodal artworks by explaining: “When I create photo collage, I fragment the original photographic ‘truths’ by rearranging sequences, layering images in time and space, and … placing words on and around the photographs. Using my female subjects’ words and my own, I write text in, and the lines of writing resemble roads making connections between territories, between generations, but refusing conquest: I do not make over my subjects’ voices into one voice or my own voice. I create an atlas for further study, a geography of identity with uncertain boundaries. The work engages multiple viewpoints, disrupts ideas about ‘the facts’ in photographs and in the autobiographical forms that chart life stories” (186).

Works Cited

- Arthur, Paul Longley. “Out of Frame.” Framing Lives. Ed. Arthur. Spec. issue of a|b: Auto|Biography Studies 29.1 p. 1–9. (2014). Print.

- Joanne Leonard: A Life in Pictures. Writ. and narr. Joanne Leonard. Play Gallery, Stamps School of Art and Design, U of Michigan (2008). Film.

- Leonard, Joanne. Being in Pictures: An Intimate Photo Memoir. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008. Print.

- Leonard, Joanne and Sidonie Smith. Interview by Sidonie Smith. “Author's Forum.” U of Michigan, Ann Arbor. 10 Dec. 2010. Transcript.

- Lippard, Lucy. “Foreword: Doubling Back.” Leonard, Being 1. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie. “Introduction: Joanne Leonard Interview.” Leonard, Interview. Print.

- Tamboukou, Maria. “Narrative Personae and Visual Signs: Reading Leonard's Intimate Photo Memoir.” Framing Lives. Ed. Paul Longley Arthur. Spec. issue of a|b: Auto|Biography Studies 29.1 p. 25–47. (2014). Print.