Abstract

In this article, the author looks at Joanne Leonard’s Being in Pictures and engages in a critical dialogue with the assemblage of visual and textual narratives that comprise her intimate photo memoir. In doing this, the author draws on Hannah Arendt’s take on narratives as tangible traces of uniqueness and plurality, political traits par excellence in the cultural histories of the human condition. Being aware of her role as a reader|viewer|interpreter of a woman artist’s auto|biographical narratives, the author situates her work within the framework of Peircian and Barthian semiotics, which allows her to move beyond dilemmas of representation or questions of unveiling the real Leonard. The artist is instead configured as a narrative persona, whose narratives respond to three interrelated themes of inquiry—namely, the visualization of spatial technologies, vulnerability, and the gendering of memory.

I didn’t start out to become a photographer. My path led me from upper-middle-class Los Angeles… to the impoverished streets of West Oakland, where I first took up my camera with conviction. This outcome was nothing I had imagined. (Leonard 4)

There are some things in life that immediately grasp your attention and interest from the very beginning. Such was my encounter with Joanne Leonard’s book Being in Pictures, which dropped as an announcement into my inbox more than four years ago, and has since captivated me both intellectually and aesthetically. The book was published in 2008 as a visual autobiography of a woman becoming an artist. The author|artist|photographer looks back into her artistic work of almost forty years and, by freezing some “moments of being,” she brings them together as an encompassing document of life. Although the photo memoir is organized along thematic units, there is also a latent chronological order in how the themes unfold, thus holding on to an Aristotelian plot of beginnings, middles, and points of arrival or moments of the present.

The author, Leonard, is a photographer and academic, and her feminist approach in photo collage and visual narratives is internationally recognized. Her work is included in art history collections (Janson; Kirkpatrick, de la Croix, and Tansey) and has been extensively cited in the scholarship of life writing, feminist studies, and critical theory (Smith and Watson; Lippard; Stanton). She has held numerous exhibitions in the US and overseas, and her work is housed in a number of museum collections in the US, including the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco and the Detroit Institute of Art.

Leonard’s photographic art emerges from the critical art scene of the radical 1960s and 1970s, a period when many artists became organically involved in the social movements of their geographies and times. As Leonard has written: “I was struggling to reconcile the largely sunny worldview of my family photographs with the daily experiences of West Oakland poverty I saw, as well as the anger and energy of the political actions in which I took part” (54). For Leonard, then, as for many of her contemporaries, art as critique is entangled with politics, with art and politics becoming constitutive of each other in what I have elsewhere theorized as “the artpolitics assemblage” (Tamboukou, “Ordinary|Extraordinary”). In this light, art is not conceived as an abstract discipline or cultural regime, but as a set of practices tightly interwoven with life and the idea of social change—a theme that runs like a red thread throughout her work.

My interest in Leonard’s visual|textual autobiography is thus very much related to my overall research project of writing feminist genealogies (Tamboukou, “Writing”). In this context, over the years I have collected, analyzed, and discussed women artists' autobiographical narratives, drawings, and paintings, making connections between textual and visual expressions of the historical constitution of the female self in art (Tamboukou, Fold). Following trails of Foucault’s genealogical approach, my inquiries always start from the present and try to deconstruct truth regimes, power|knowledge relations, and forces of desire, which have created a plane of consistency for “common-sense” perceptions of the persona of the woman artist. “What is the present of women artists today?” I have asked. “How have they become what they are and what are the possibilities of becoming other?” It goes without saying that Leonard’s visual autobiography has been taken as an exemplary case study of my genealogical inquiries.

In this article, I want to create a dialogical scene wherein visual and textual narratives create a milieu for women’s lives to take up meaning within the web of human relations. In order to do this, I draw on Hannah Arendt’s conceptualization of narratives as crucial in making sense of the human condition. Drawing on the Aristotelian notion of “energeia,” Arendt’s thesis is that “action as narration and narration as action are the only things that can partake in the most ‘specifically human’ aspects of life” (Kristeva 41). In acting and speaking together, human beings expose themselves to each other, reveal the uniqueness of “who” they are, and, through taking the risk of disclosure, connect with others. In this light, narration creates conditions of possibility for uniqueness, plurality, and communication to be enacted within the Arendtian configuration of the political. As the only tangible traces of the human existence, stories in Arendt’s thought evade theoretical abstractions and contribute to the search of meaning by revealing multiple perspectives, while remaining open and attentive to the unexpected, the unthought-of. What is particularly interesting in adopting the Arendtian thesis is the visuality of the narrative milieu, which creates conditions of possibility for existential questions to be raised, but I will return to the analysis of the visual later on. Here, I want to consider Adriana Cavarero’s argument that narrative should be considered as an alternative discourse, challenging traditional philosophical questions around the subject: “We could define it as the confrontation between two discursive registers, which manifest opposite characteristics. One, that of philosophy, has the form of a definite knowledge, which regards the universality of Man. The other, that of narration, has the form of a biographical knowledge, which regards the unrepeatable identity of someone. The questions which sustain the two discursive styles are equally diverse. The first asks ‘what is Man?’ The second asks instead of someone ‘who he or she is’” (13).

Following Arendt’s philosophy, Cavarero has argued that the act of narration is immanently political, relational, and embodied: “to act and speak, to leave one’s safe shelter and expose one’s self to others and, with them, be ready to risk disclosure. This would be the first political condition for revelation: demonstrating who I am, and not what I am” (Kristeva 16). To the Arendtian line that human beings as unique existents live together and are constitutively exposed to each other through the bodily senses Cavarero adds the “narratability” of the self—its constitution by the desire of listening to her story being narrated.

In thus looking into Leonard’s visual autobiography, what I argue is that through the artistic entanglements of textual and visual narratives, it opens up a performative scene—a dialogic space wherein the autobiographical subject, the researcher, and the reader meet, interact, and negotiate meaning about subjects and their world. It has to be noted here that although Arendt highlights the importance of stories in creating meaning, she makes the distinction between revealing meaning and defining it, thus pointing to the impossibility of pinning down what stories are about or what subjects should be or do. “It is true,” she notes, “that storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it” (Dark 105). Here, however, Arendtian scholars have pointed out that “meaning” as an existential concept remains rather elusive in Arendt’s work—“a jigsaw puzzle, whose pieces are distributed among actors in the public realm, spectators, poets, historians and philosophers” (Hinchman and Hinchman 164).

In this light, Being in Pictures becomes a site of mediation and communication, enabling the emergence of a multiplicity of meanings and traces of truth. Moreover, Leonard, as the autobiographical subject of the analysis, far from being essentialized, pinned down in a fixed subject position, or encased within the constraints and limitations of her story, becomes a “narrative persona” (Tamboukou, Fold 179), who responds to the theoretical questions and concerns of the researcher. In configuring Leonard as a “narrative persona,” I have followed Deleuze and Guattari’s juxtaposition of “conceptual personae” in philosophy and “aesthetic figures” in art, as discussed in their last collective work, What Is Philosophy?

“Philosophy constantly brings conceptual personae to life,” Deleuze and Guattari have suggested (62)—the Socrates in Plato, the Dionysus in Nietzsche, and the Idiot in Descartes becoming their exemplars for the most well-known conceptual personae in the history of philosophy. The philosopher speaks through her conceptual persona, keeping a critical distance from what is being said and from the subject of enunciation. It is a third person—the conceptual persona, not the philosopher—that says “I,” since there is always a multiplicity of enunciations and subjects in the work of philosophy.

While philosophy invents conceptual personae, art creates aesthetic figures: “the great aesthetic figures of thought and the novel but also of painting, sculpture, and music produce affects that surpass ordinary affections and perceptions, just as concepts go beyond everyday opinions” (Deleuze and Guattari 65). Conceptual personae and aesthetic figures “may pass into one another, in either direction,” but should not be conflated, Deleuze and Guattari note (177).

Although my initial idea of the narrative persona comes from a synthesis of Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the conceptual persona of the philosopher and the aesthetic figure of the artist as explicated above, it is in Arendt’s work again that the concept has been narratively grounded. As Arendt notes in her book On Revolution, the roots of the persona are to be found in ancient drama, wherein it has a twofold function: (a) as a mask disguising the actor in the theater and (b) as a device that, although disguising, allows the voice of the actor to sound through (106). If we follow the historicity of the concept, however, in Roman times the persona passes from the theater to the legal realm, and it means a legal personality, a “right-and-duty bearing person,” a Roman citizen, not any natural person. So what we have is the drama persona and the legal persona.

In this context, the notion of the narrative persona in my work is taken as a conceptual and aesthetic figure who acts and whose story we can follow in the pursuit of meaning and understanding. But the fact that we follow the story of the narrative persona does not necessarily mean that this story represents the real essence or character of who Leonard really is. This is not to deny that Leonard is a real person, but to denote the limitations of her, and indeed anybody’s, autobiographical stories to convey the essence of who their author is. As Arendt has aptly put it: “nothing entitles us to assume that [man] has a nature or essence in the same sense as other things” (Human 10). But the lack of essence does not necessarily lead to the death of the autobiographical subject. While rejecting essence, Arendt theorizes human existence, “life itself, natality and mortality, worldliness, plurality and the earth,” but here again she emphasizes the fact that we are not reducible to the conditions of human existence (11). Instead of a unified and autonomous subject, there are instead nomadic passages and subject positions that the narrative personae of my inquiries take up and move between, while writing and|or visualizing stories of the self (Tamboukou, Fold). As Leonard puts it at the very beginning of her book: “My path led me from upper-middle-class Los Angeles, where I was born, to the impoverished streets of West Oakland, where I first took up my camera with conviction” (4). Moreover, it is through their stories that certain concepts, ideas, and events can be expressed, rehearsed, and dramatized so that their enactment can create a scene for dialogic exchanges, communication, understanding, and action.

Further considered within the legal dimension of the Roman tradition in Arendt’s analysis, the narrative persona takes up a position in discourse and assumes her rights as a legal subject. This positioning does not essentialize her either; rather, it creates a person with whom one can be in dialogue, but also to whom one is responsible: “a right-and-duty bearing person, created by the law and which appears before the law,” as Arendt has pithily remarked (On Revolution 107). In the discussion of this article, Leonard thus becomes a persona created by her narrative but to whom I am accountable, having taken up the responsibility of presenting her story as an Arendtian design that has a meaning; the latter is open to interpretation and negotiation between you as audience|viewers|readers, myself as an author and narrative researcher, and my narrative persona, whose stories should be open to all.

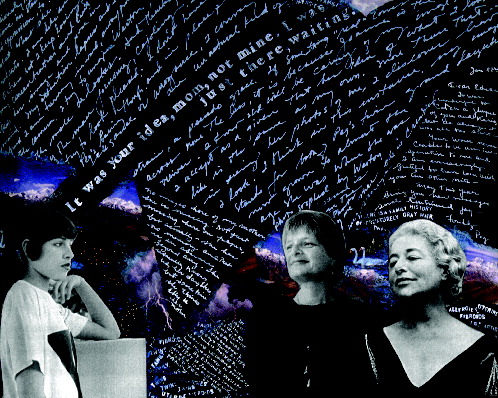

Emerging in passages and crossroads between conceptual personae and aesthetic figures, Leonard has thus been conceptualized as a narrative persona in my engagement with her visual autobiography. Indeed, her photographs and the narratives that are wrapped around them create a plane of consistency for entanglements of power relations and forces of desire to be charted. But what is the role of the visual in this entanglement? And how is it conceptualized in my analysis? As Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson have pointed out, particularly in discussing Leonard’s Being in Pictures, “photographs never simply illustrate a written narrative. Each photo tells a separate story and taken together, they form a separate, often conflicting system of meaning” (96). What is important to remember here is that in putting Being in Pictures together, Leonard has actually created an artist’s book, where photographs, artistic images, and tissues of narrative have been artfully brought together in the tradition of the collage. What Leonard has therefore created is what I have called “a narrative assemblage” of stories and images (Tamboukou, Fold) that, rather than representing the real, simply respond to the world, opening up dialogical scenes where the readers|viewers are openly invited to participate. In this light, the visual analysis of Leonard’s autobiographical acts has been framed within Peircian and Barthian semiotics, which I will briefly explicate below.

In Peirce’s theory, signs constitute the world; thinking is a sign and even human beings are signs. How does the sign-relation function? Peirce introduces the role of the “interpretant” in the sign-relation and, in this sense, a triadic relation is configured between the sign or “representamen,” the “object” (which is what is being represented), and the “interpretant.” Within the cycle of the triadic sign-relation, Peirce further introduces a tripartite taxonomy of signs depending on the indispensability of the presence of the “interpretant” and the “object” in the configuration of the relation.

In discussing Peircian semiotics, West has noted that “an icon looks like the thing it represents, an index draws attention to something outside the representation and a symbol is a seemingly arbitrary sign that is, by cultural convention, connected to a particular object” (41). Peirce’s tripartite schema makes interesting connections with Barthes’s notions of the “operator,” the “spectator,” and the “spectrum”: “The Operator is the Photographer, the Spectator is ourselves, all of us who glance through collections of photographs… and the person or thing photographed is the target, the referent… which I should like to call the Spectrum” (9). In thus taking Peircian and Barthian semiotics as the framework of my approach, what I propose is that, taken as a Peircian index, Leonard’s images generate meaning, draw the spectator’s attention to something outside the representation, and inspire her to imagine worlds beyond what has been or can be merely represented.

In this context, Leonard's narrative assemblages respond to the theoretical questions that my genealogical inquiries have raised: how have women artists become what they are and what are the possibilities of becoming other? Such questions and themes revolve around women artists' agonistic relations with space, place, and creativity. As I have discussed elsewhere (Tamboukou, Fold), the auto|biographical narratives and visual images that comprise the archive of my genealogical inquiries annihilate binary oppositions and open up planes of analysis in the intermezzo of psychosocial and cultural formations: between the inner and the outer; the public and the private; submission and independence; pain and pleasure; Eros and love; solitude and communication; estrangement and homeliness; movement and stasis; and, ultimately, life and art—the central conceptual pair of my genealogical inquiries. What I thus want to do in the following sections of this article is to try and retrace three sets of “lines of flight” that Leonard as a narrative persona has followed in creating her autobiography as an assemblage of textual and visual narratives: the visualization of spatial technologies, vulnerability, and the gendering of memory.Footnote1

Becoming an Artist: Visualizing Spatial Technologies of the Self

When does one become an artist? This is the difficult question that Leonard grapples with at the very beginning of her intimate memoir: “It is not easy for anyone to mark the moment of realization: ‘Now! I’ve become an artist. … becoming an artist might seem to have happened by accident” (6). Interestingly enough, the question is framed by two pictures of her kitchen (6, 7) and a picture of her studio (6). If you cannot freeze the moment of becoming an artist, you can visualize the spaces that created conditions of possibility for becoming an artist. Indeed, Leonard’s self-realization as an artist is spatially framed and narrated: “I had to take myself seriously as an artist in order to allow myself the time, money and space for my art … I built a darkroom and, later, a studio when I could have fixed up a kitchen” (6). The moment of building a studio is a decisive event in women’s self-recognition as an artist, and is a constant refrain in their autobiographical stories (Tamboukou, Fold). Women artists have written about their studios and have represented them in a variety of visual modes and media. “A studio of her own” has thus become a recurrent spatial theme in the constitution of the female self in art. What is also important is that the artist’s studio is very rarely a demarcated and independent space, but often exists in the margins of domestic spaces, while its boundaries are often reconfigured and continually crossed; “a studio of her own” is thus a labile space, a floating platform for a woman to inhabit temporarily while moving along nomadic paths or following lines of flight in becoming an artist.

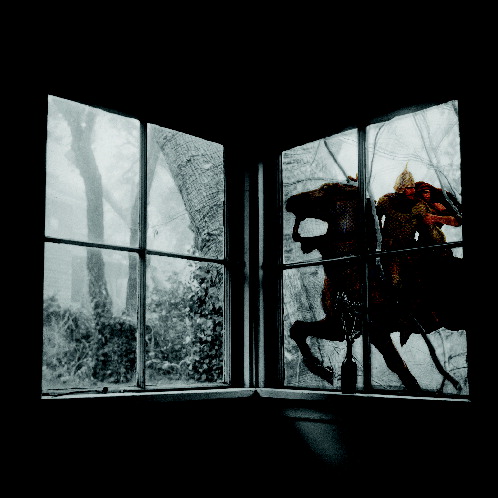

Visualizing domestic spaces, and particularly her kitchen, thus becomes a recurrent theme in Leonard’s photo memoir, particularly when in movement. It is while traveling for the 1972 Winter Olympics in Japan that she realizes “that such a life would be incompatible with the quieter pleasure I took in working out ideas in my studio” (89), hence the snowed-under kitchen photograph () is juxtaposed with a snow-scene silver print of the Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan (88). While her countertop photographs have often been interpreted as expressing the frustration “of a woman trapped in the kitchen” (166), for the photographer they were a humorous response to how it felt to have moved from the sunny Bay Area to wintry Michigan in order to take up a teaching position at the university there. Within the analytical context of Peircian semiotics, the snowed-under countertop is not a symbol or an icon, but an index, drawing attention to something outside the representation—what it means to move, in this particular case. But, of course, this is a sign-reading that goes through the artist as an “interpretant,” and does not preclude other viewings and interpretations.

FIGURE 1. Joanne Leonard, Romanticism Is Ultimately Fatal, 1972, fine-grain positive transparency, selectively opaqued, over collage, Collection of Manuel Neri.

FIGURE 2. Joanne Leonard, Countertop Snowing, 1980, silver print, water-soluble wax pastel and gouache, private collection.

As an artist, as well as an academic, Leonard is fully aware of the complexities in not just how we look at photographs, but also how we perceive private and public spaces: “if the set of images succeeds, it’s because it suggests, I think, something more complex about the tensions and pulls of the world inside and the world outside ‘home’—which included my university responsibilities,” she writes about the Countertop Landscapes and Skylines series (166).

In highlighting tensions between spaces inside and outside “home,” Leonard raises some critical questions around domesticity. Indeed, how is the domestic to be perceived within the spatial context of a woman artist’s life? Domesticity has been a hot area of feminist theorization, and a lot of feminist ink has been spilt on arguments linking women’s liberation with the rejection of domestic ties, as well as post-feminist counter-arguments challenging constructed dichotomies between the domestic, the private, and the public.Footnote2 Domesticity has also been challenged in art histories revolving around the Bloomsbury interiors, in particular. In writing about the “Bloomsbury rooms,” Christopher Reed has shown how a different ideal of domesticity was amongst the concerns of the Bloomsbury Group as part of the aesthetics and politics of everyday life. In looking into the architectural and decorative arrangements of English interiors created by members of the Bloomsbury Group, and particularly Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, and Roger Fry, Reed has argued that while criticizing mainstream domestic culture, the Bloomsbury Group’s alternative domesticity was an important subculture within modernism. What I argue is that it is this idea of “alternative domesticity” that emerges from Leonard’s photographs of spaces inside the home and runs like a red thread throughout her work in general, and her photo memoir in particular.

In this context, the snow on the kitchen countertop functions as a Barthian “punctum,” a sign that erupts from the photograph and wounds the eye, as it makes the viewer aware of the “co-presence of two discontinuous elements, heterogeneous in that they do not belong to the same world” (Barthes 23)—the snow of the outside world and the countertop of the kitchen interior. But the punctum in Barthes’s analysis always functions in relation to the “studium,” a kind of common-sense understanding and taste through which we look at and make sense of photographs, without any passionate attachment to them. As Barthes writes: “the studium is that very wide field of unconcerned desire, of various interest, of inconsequential taste: I like|I don’t like” (27). Here, it is obvious that the photograph of a kitchen countertop is a field of “unconcerned desire” par excellence. The presence of snow in the kitchen, however, irrevocably unsettles our understanding of what kind of place a kitchen is, and therefore disrupts the studium of domestic spaces. Moreover, as a punctum, the snow in the kitchen is always linked to a subjective interpretation and can never sit comfortably within any kind of generalized or common-sense understanding. The snow becomes the visual sign that disturbs the studium and, at the same time, attracts the viewer to the image, creating strong affective ties with it: “a detail attracts me,” writes Barthes. “I feel that its mere presence changes my reading, that I am looking at a new photograph, marked in my eyes with a higher value” (42).

Leonard’s visualization of the porous boundaries between the inside and the outside also responds to Iris Marion Young’s argument that “house and home are deeply ambivalent values” (252). Drawing on Heidegger’s theorization of dwelling as a fundamental existential mode of being-in-the-world, Young has pithily noted that Heidegger has divided dwelling into building and preservation, tacitly privileging the former over the latter. Taking issue with this deeply gendered division, Young has focused on the importance of preservation and has revisited home “as a support for personal identity without accumulation, certainty or fixity” (254).

Since Leonard is a single mother, both building and preservation are tightly interwoven in her spatial orientation as an artist. As already noted, she writes about her decision to build a studio instead of a kitchen, while, in the mood of preservation, putting in order a messy living room at the end of a very troublesome day feels like reorienting her life and reassuring her concerns as a single mother. The two 1976 black-and-white photographs () that document this transformation are, indeed, unique traces of such spatial modes of being-in-the-world: “One evening I sat down in our main room on my couch-bed and saw toys and clothes scattered everywhere. A total mess! Feelings of being alone and disconnected sometimes hit when I was tired. That night those feelings joined a long day’s work and single parent life to leave me limp and despondent.… I took out a kitchen stool to record the household chaos, then cleaned up and, savoring my small triumph on the home front, rephotographed” (Leonard 130).

FIGURE 3. Joanne Leonard, Living Room|Dining Room|Bedroom, Messy View and Tidy View, 1976, silver prints.

Leonard’s spatial technologies frozen in the two views of the tidy|untidy room|dining room|bedroom are juxtaposed with a peaceful black-and-white photograph of Julia’s bedroom, taken in 1975. Julia’s presence is, indeed, dominant in Leonard’s photo memoir, and has initiated a number of comments and essays around the mother–daughter relationship theme of the whole project (see Jigarjian and Mestrich). What has been less discussed, however, is a theme that I want to look at in the next section: the visualization of vulnerability in Leonard’s photographs of her beloved daughter, Julia.

Visualizing Vulnerability

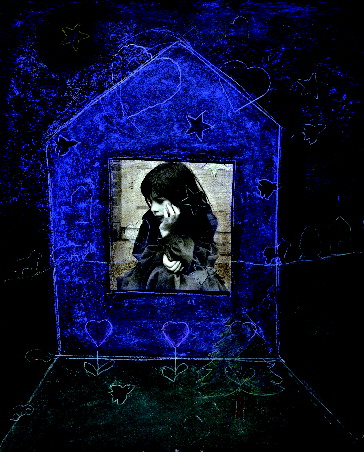

“In 1983 President Reagan was building up huge stockpiles of antiballistic missiles. Enough missiles were already on hand, I had read, to destroy the world many times over. The president justified the missile buildup’s huge expense by saying it would help the United States close ‘a window of vulnerability’, a phrase I found poetic and suggestive for my imagery” (Leonard 154). As Leonard explains here, the conceptual idea of creating the series Julia and the Window of Vulnerability came from the political rhetoric of a phrase, which she found suggestive for her work. Vulnerability is central in the political discourse that motivates Leonard’s artistic intervention; but while military expenses are aiming at “clos[ing] a window of vulnerability,” the artist’s work is opening it up, putting a child figure—her daughter Julia—at its very center. It is this reversal of the notion of vulnerability that I want to consider here by returning to Arendt’s political philosophy.

Vulnerability, in Arendt’s thought, is a precondition of what it means to be human: we are born in the world completely dependent on other human beings, who promise to look after us, protect us, and guide us into the web of human relations—a process that is always precarious and unpredictable. This is why “the power of making promises has occupied the centre of political thought over the centuries,” Arendt remarks (Human 244). In this light, human relations depend on and are shaped by this condition of vulnerability, which can never change, let alone be annihilated or closed down, like Reagan’s window. In this sense, vulnerability becomes a condition sine-qua-non of the political, conceptualized in Arendt’s thought as the practices of acting and speaking together. Drawing on Arendt, Butler has discussed the political discourse of “invulnerability” and its discontents and effects: “it seems to me that implicitly what’s being promised is that, as a major First World country, the US has a right to have our borders remain impermeable, protected from incursion, and to have our sovereignty guarantee our invulnerability to attack; at the same time, others, whose state formations are not like our own, or who are not explicitly in alliance with us, are to be targeted and presumptively treated as expugnable, as instrumentalizable, and certainly not as enjoying the same kind of presumptive rights to invulnerability that we do. So it’s led me to think about the differential distribution of vulnerability and, in a corollary way, the differential distribution of grievability—whose lives are worth grieving and whose are not?” (Bell 147).

For Butler, vulnerability is at the heart of what it means to give an account of oneself and, more importantly, of the ethical implications of responding to it, since narration is a process where questions of the self are raised—albeit not fully answered—and ethical actions and responsibilities are enacted. As Bell has pithily noted, in developing her thought on responsibility and ethical action, Butler has drawn on Arendt’s work and particularly her “emphasis on a plurality within the subject’s sociality”—that is, Arendt’s “two-in-one”-ness (147).

Although created well before Butler’s theorization of “the differential distribution of vulnerability” as discussed above, Julia and the Window of Vulnerability beautifully visualizes the futility of the political discourse of invulnerability, and also brings to the fore the Arendtian notion of natality through the figure of the artist’s child: “The miracle that saves the world, the realm of human affairs, from its normal, ‘natural’ ruin is ultimately the fact of natality, in which the faculty of action is ontologically rooted. It is, in other words, the birth of new [men] and the new beginning, the action they are capable of by virtue of being born. Only the full experience of this capacity can bestow upon human affairs faith and hope, those two essential characteristics of human existence” (Arendt, Human 247).

FIGURE 4. Joanne Leonard, Julia and the Window of Vulnerability (1), 1983, silver print with chalk pastel, Collection of René di Rosa.

Beginning is, indeed, a crucial concept in Arendt’s theoretical configuration of the human condition: “Men are equipped for the logically paradoxical task of making a new beginning because they themselves are new beginnings and hence beginners.… the very capacity for beginning is rooted in natality, in the fact that human beings appear in the world by virtue of birth” (On Revolution 211). Existentially inherent in the human condition, the notion of beginning further shapes Arendt’s understanding of the political, an arena where new beginnings are always possible: “the essence of all, and in particular of political action, is to make a new beginning” (“Essays” 321). As widely noted and discussed, natality marks Arendt’s philosophy as a radical departure from the Heideggerian orientation toward death, and founds her philosophy of and for life (see Cavarero). Moreover, the idea of freedom as ontologically inherent in the human condition is closely interrelated with new beginnings in Arendt’s thought: “Because he [sic] is a beginning, man can begin; to be human and to be free are one and the same” (Between 166).

In this context, it is no wonder that the photograph of a child becomes such a powerful visual sign in the work of a politically committed artist, who is also a mother. Moreover, as Leonard writes, Julia and the Window of Vulnerability was not just a milestone in her career, but, most importantly, a new beginning in her work. What is also very interesting in Leonard’s narrative is that this work was not a mega event, a bright moment of genius inspiration in the head of the artist, but rather the effect of a summer-long process of engaging with Julia’s world and thinking about world problems through her love and care for her daughter: “I worked with great intensity and remember how important it was to me to suggest something of my heightened anxieties about the world and Julia’s safety, particularly in the political climate of that time” (154). Indeed, Leonard gives a detailed account of the 1983 summer when she created four versions of Julia and the Window of Vulnerability on a table in a small crowded bedroom, using a white pencil to trace the outlines of not only small cars, trees and hearts, but also stars, the moon and a missile onto the surface of the photograph. She thus created a miniature of the world and the cosmos not only as a backdrop to the child’s photograph, but also as a scene wherein the child is caught in a pensive mood, naturally unaware of the risks of the world that she has been thrown into. Julia’s portrait is thus constituted as a Barthian “closed field of forces” (Barthes 13), a battlefield of power relations at play, wherein she is inevitably entangled. The “operator,” who is also a mother, artfully visualizes her ethical responsibility through drawing and painting, and, in doing so, invites the “spectator” to take up a position vis-à-vis vulnerability, as well as its unequal distributions. In this light, the Arendtian “two-in-one”-ness that the mother-daughter|operator-spectrum enacts opens up in the plurality of the spectators' world.

As Susan Sontag has astutely remarked: “a photograph is not only an image... an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stenciled off the real” (154). In discussing the material details of her art work with Julia and the Window of Vulnerability, Leonard writes that she actually used a book of stencils to draw the outlines of the worldly objects onto the surface of the photograph and, since the stencil book had the word “mom” in it, she stenciled that too. When the work was published, “I was tickled that the word mom had made it into fine art history,” she writes, thus creating a trace “on behalf of mother-artists everywhere” (Leonard 156).

Thus, Julia and the Window of Vulnerability is a forceful visual enactment of what Cavarero has theorized as the neglected I|you relationship and particularly the marginalization of the singular “you”: “the ‘you’ is a term that is not at home in modern and contemporary developments of ethics and politics,” she has written (90). Butler is also interested in the dyadic encounter of the narrative scene and the ethical responsibilities that arise from it, despite the fact that the stories emerging from this encounter will always be incomplete and constrained by prior discursive limitations: “The narrative authority of the ‘I’ must give way to the perspective and temporality of a set of norms that contest the singularity of my story” (37). Either constitutive of narratable and relational subjectivity, as in Cavarero, or always falling short of the task, as in Butler, narration is a process where questions of the self are raised, thus opening up scenes for the enactment of ethical actions and responsibilities. As Butler aptly puts it: “to take responsibility for oneself is to avow the limits of any self-understanding” (83).

In light of the above and within the milieu of motherly love for her daughter, visual and textual narratives are closely intertwined: “in love, the exposition and relational character of uniqueness plays out one of its most obvious scenes,” Cavarero eloquently writes (109). Moreover, the theme of motherly love as forcefully inscribed in Leonard’s photographic collage is further interlaced with feminism, as an imagined radical future as well as a wider political project of an Arendtian love for the world (Tamboukou, “Love”).

If stories are always relational, then the subject positions that their characters can occupy either as readers|viewers or writers|artists, or both, are always already relational as well as vulnerable, and therefore political in the Arendtian sense: they depend on each other for their mere survival and they exist through their immersion in narratives—be they textual or visual—through which they become entangled in the web of human relations. Stories are also crucial to how memories of the self and the world are constituted and indeed sustained, and it is the mnemonic practices in Leonard’s photo memoir that I wish to discuss next.

Visual Traces of the Gendering of Memory

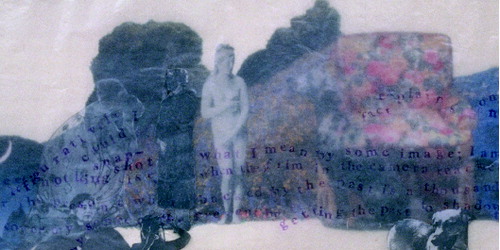

One of the urgent questions that have been raised in the burgeoning literature on memory studies is “how the category of gender can be integrated into debates on memory culture” (Paletchek and Schraut 7). Leonard’s Moments of Being () is, I argue, an early artistic intervention in the quest of how gender can shape a culture of memory that incorporates and validates women’s experience. Here it is important to consider the genealogical lines of women artists' intervention in the area of memory studies, as Leonard does in acknowledging Virginia Woolf’s impact on her work with photographs, time, and memory: “I made Moments of Being in the mid-1980s after I had read the book Moments of Being: Unpublished Autobiographical Writings in 1985. … In one essay in the collection Woolf likens memory to a net suspended in water from corks, where the corks (like the few moments that one remembers over the years) are all that rise to the surface. Woolf’s vivid textual imagery of memory in her writings interested me hugely; I used a set of alphabet rubber stamps to stamp passages from Woolf onto the glassine” (178).

FIGURE 5. Joanne Leonard, Moments of Being (detail), 1990, collage on off-white paper with stamped lettering and additional collage of glassine overlay.

Woolf’s image of memories floating like corks, but still connected to a net, gave Leonard the idea of printing her memory photographs on thin photographic paper; in her attempt to create translucent effects, she waxed the thin photographic prints or photocopied pages, and also used glassine layers on some of her pieces (see Leonard 180). Here again, she drew on Woolf’s imagery of remembering: “One of the ideas I had about the overlay was that it veils the underlying imagery and creates a kind of distance suggesting memories obscured by time, as in Woolf’s wonderful word picture of remembering: ‘lying in a grape and seeing through a film of semi-transparent yellow’, a quote I found in ‘A Sketch of the Past’ in Moments of Being” (Leonard 180).

Leonard’s photographic techniques and collage practices of visualizing the experience of remembering reverberate here with Sontag’s suggestion that photographs are not so much an instrument of memory—insignificant and shallow, according to Proust, in that they reduce the past into visual representations. Rather, photographs are an invention of the past or a replacement of it, Sontag argues (165). But what does it mean to use photographs as tools for reinventing the past? Drawing analogies between Balzac’s literary art in magnifying details and the photographic operation of enlargement, Sontag has highlighted what I would call the “art of the detail”—the artistic practice through which “the spirit of an entire milieu could be disclosed by a single material detail. … the whole of life … summed up in a momentary appearance” (159). What I argue is that Leonard’s art of freezing time frames offers some very powerful visual images of “momentary appearances,” which are brought to the fore through the art of magnifying details, as in her Roots and Wings (): “I made Roots and Wings when my parents were elderly. My dad had liver cancer, and my mom’s memory was failing. In this piece I sought to suggest a continuum from my parents to my daughter—a passage of time. I've used a cup of coffee or teapot to refer to myself alone, here as in other works” (183).

FIGURE 6. Joanne Leonard, Roots and Wings, 1988, silver print of photographs and photograms with collage and gouache, Collection of Barbara Raymond.

Roots and Wings is an artwork that attempts to freeze the passage of time by bringing together significant “moments of being” in the artist’s family. The backdrop of the collage is a dinner table with magnified images of domestic objects, such as candlesticks, a teapot, coffee pots, and cups, which the artist has often used in her work to represent herself. The artist’s parents are depicted as a romantic dancing couple, and also by a magnified framed photograph taken at the very end of her father’s life, while her daughter Julia is drawn as a flying figure, ready to throw herself into the open future. In cramming together magnified objects and miniature figures in the visual field of a dinner table, the artist creates an artful image of the space|time continuum, within which her family history unfolds and the passage of time is visually captured.

In further discussing her work with time and memory, Leonard has noted that finding a visual vocabulary to describe female worlds and represent gendered biographies has been a central preoccupation of her work over the years. Her search for artistic practices in gendering memory has actually led her to use more and more text in her collages. The use of “text as image” (Leonard 190) is particularly striking in her work that revolves around her mother’s gradual loss of memory due to Alzheimer’s disease: “Absence and loss are all but unrepresentable through traditional photography since photography inherently depends on presence—a presence recorded by the camera,” Leonard (190) notes, in agreement with Barthes that “every photograph is a certificate of presence” (87). Her Four Generations, One Absent () is such an attempt at using collage, which includes a great deal of “text as image.” In this artwork, the artist’s mother is represented by an empty space “because her mental decline, as well as inability to travel, meant she was absent (figuratively and literally) when I travelled to Los Angeles to photograph EllyFootnote3and Julia at what had once been my grandmother’s house” (Leonard 190).

FIGURE 7. Joanne Leonard, Four Generations, One Absent, 1991–92, silver print from laser-copy transparencies with writing stamped lettering and collage.

The rich use of “text as image” here brings to mind Sontag’s acute observation that “a photograph could also be described as a quotation” (71). What is interesting with Leonard’s text images is that the photographic collages of exploring female identity, biography, and memory are, indeed, full of quotations—literally and not just metaphorically. Except that the quotations that fill Leonard’s artwork are not like Walter Benjamin’s books of quotations, which Sontag has discussed (75). They are taken from Leonard’s family histories and inserted in her photographic collages as tissues of narrative that keep together slices and moments of auto|biographical memory. In the same way that the past becomes for Benjamin “the most surreal of subjects—making it possible … to see a new beauty in what is vanishing” (Sontag 76), family history becomes for Leonard a source of inspiration for her artwork, as she attempts to freeze in pictures what is rapidly changing and vanishing. In collecting snapshots of the past and keeping them together through the art of the photo collage, Leonard follows the tradition that Sontag has astutely identified: “Photographers, operating within the terms of the Surrealist sensibility, suggest the vanity of even trying to understand the world and instead propose that we collect it” (82).

How is gender inserted in these memory works? Leonard is clear that her overall project as an artist is to create visual ways of representing female worlds, drawing on her immediate family history of four generations of women. Although there is a lot of “sameness” in her family—the artist herself being an identical twin—through her artwork she strives to highlight differences by visually representing what Bakhtin has most influentially theorized as polyphony and heteroglossia—quite simply, allowing multiple voices to be heard and different world views to be expressed through her text images:

When I create photo collage, I fragment the original photographic “truths” by rearranging sequences, layering images in time and space and… placing words on and around the photographs. Using my female subjects’ words and my own, I write text in, and the lines of writing resemble roads making connections between territories, between generations, but refusing conquest: I do not make over my subjects’ voices into one voice or my own voice. I create an atlas for further study, a geography of identity with uncertain boundaries. The work engages multiple viewpoints, disrupts ideas about “the facts” in photographs and in the autobiographical forms that craft life stories. (Leonard 186)

As I have written elsewhere, autobiographical work is always fragmented and unity is only a fantasy (Tamboukou, “Good”). What Leonard’s artistic practices do is highlight the fragmented nature of our lives and of ourselves, map the inherent differences of the human condition, and unveil the fantasy of its unity. In this light, her memory-works create a rhythm of difference and repetition through bringing together visual representations of auto|biographical fragments.

Stories and Images

In responding to Leonard’s intimate photo memoir, in this article I have offered some fragments of thought around women artists' textual and visual narratives in the context of my overall project of writing a feminist genealogy of the female self in art. In reading Leonard’s stories that weave around a rich range of photographs and artwork in the photo-collage genre, I have resisted the biographical impulse of discovering the truth about my subject. At the same time, I have also avoided the post-structuralist fragmentation of the subject by holding onto the Arendtian idea of pursuing meaning through following auto|biographical traces of the self. In recognizing and acknowledging the multiplicity of meanings that life stories can reveal, I have particularly followed three themes in Leonard’s photo memoir: spatial technologies of becoming an artist, vulnerability as an ontological precondition of the political, and visual trends in gendering auto|biographical memories. Interestingly, the spatial theme of the importance of a studio of one’s own has come up in Leonard’s photo memoir; what has been problematized, however, is the gendered division between domestic and public spaces. Leonard’s subject position as an artist, but also a single mother, has shown how porous the boundaries of spaces “inside” and “outside” the home can be. It is also from the position of the artist-as-mother that Leonard has problematized the discourse of invulnerability and highlighted the importance of ethical responsibility to others through the mother-daughter dyadic relationship as expressed in her artwork. Leonard’s engagement with the attempt to visualize time and memory has finally created an early and artful intervention in what still remains an underdeveloped theoretical field: the inclusion of gender as an analytical category in cultural studies of memory.

In reading and analyzing Leonard’s visual and textual narratives, I have deployed methodological strategies framed within Peirce’s tripartite schema of sign relations, as well as Barthes’s theorization of photographs alongside the practices, emotions, and intentions of the operator, the spectator, and the spectrum. In this context, Leonard has emerged as a narrative persona whose textual and visual stories have responded to the genealogical questions of my inquiry: what is the present of women artists today? How have they become what they are and what are the possibilities of becoming other? Moreover, how do ethics, aesthetics, and politics create an assemblage for making sense of the historical constitution of the self and the radical openness of its futurity?

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Joanne Leonard for trusting me to convey some thoughts around her rich and beautiful autobiographical work, and for kindly giving me permission to cite from her work and reproduce her artwork.

Notes

1. “Lines of flight” is a concept from Deleuze and Guattari’s philosophy, denoting a detachment from social, political, and cultural grounds; it is another way of theorizing resistance, as I have discussed elsewhere in my work with women artists (Tamboukou, Fold).

2. For an overview of this debate and discussion of the literature, see, amongst others, Felski; Giles; and Hollows.

3. Elly (Eleanor Rubin) is Leonard's twin sister.

Works Cited

- Arendt, Hannah. Essays in Understanding 1930–1954: Formation, Exile and Totalitarianism, Ed. J. Kohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1994. Print.

- Arendt, Hannah. Between Past and Future: Eight Exercises in Political Thought. 1961. London: Penguin, 2006. Print.

- —. The Human Condition. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1998. Print.

- —. Men in Dark Times. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1968. Print.

- —. On Revolution. London: Penguin, 1990. Print.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Ed. Michael Holquist. Austin: U of Texas P, 1981. Print.

- Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. Trans. Richard Howard. London: Vintage, 2000. Print.

- Bell, Vikki. “New Scenes of Vulnerability, Agency and Plurality: An Interview with Judith Butler.” Theory, Culture & Society 27.1 (2010): 130–52. Print.

- Butler, Judith. Giving an Account of Oneself. New York: Fordham UP, 2005. Print.

- Cavarero, Adriana. Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood. Trans. Paul A. Kottman. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Félix Guattari. What Is Philosophy? Trans. Graham Burchell and Hugh Tomlinson. London: Verso, 1994. Print.

- Felski, Rita. Time: Feminist Theory and Postmodern Culture. New York: New York UP, 2000. Print.

- Giles, Judy. The Parlour and the Suburb: Domestic Identities, Class, Femininity and Modernity. Oxford: Berg, 2004. Print.

- Hinchman, Lewis P., and Sandra K. Hinchman. “Existentialism Politicized.” Hannah Arendt: Critical Essays. Ed. Hinchman and Hinchman. New York: State U of New York P, 1994. 143–78. Print.

- Hollows, Joanne. “Can I Go Home Yet? Feminism, Post-Feminism and Domesticity.” Feminism in Popular Culture. Ed. Joanne Hollows and Rachel Moseley. Oxford: Berg, 2006. 97–118. Print.

- Janson, Anthony F. History of Art. New York: Abrams, 2004. Print.

- Jigarjian, Michi, and Qiana Mestrich, eds. How We Do Both: Art and Motherhood. New York: Secretary, 2012. Print.

- Kirkpatrick, Diane, Horst de la Croix, and Richard Tansey, eds. Gardner’s Art through the Ages. 9th ed. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1991. Print.

- Kristeva, Julia. Hannah Arendt: Life Is a Narrative. Trans. Frank Collins. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2001. Print.

- Leonard, Joanne. Being in Pictures: An Intimate Photo Memoir. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 2008. Print.

- Lippard, Lucy. Inside and Beyond: Photographs by Joanne Leonard. Catalog essay. Austin, TX: Laguna Gloria Art Museum, 1979. Print.

- Paletschek, Sylvia, and Sylvia Schraut, eds. The Gender of Memory: Cultures of Remembrance in Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Europe. New York: Campus, 2008. Print.

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. “Sign.” Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic by Charles Sanders Peirce. Ed. James Hoopes. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1991. 239–40. Print.

- Reed, Christopher. Bloomsbury Rooms: Modernism, Subculture and Domesticity. New Haven: Yale UP, 2004. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2010. Print.

- Sontag, Susan. On Photography. London: Penguin, 1979. Print.

- Stanton, Domna C., ed. Discourses of Sexuality: From Aristotle to AIDS. Ann Arbor: U of Michigan P, 1992. Print.

- Tamboukou, Maria. “Good Night and Good-Bye: Temporal and Spatial Rhythms in Piecing Together Emma Goldman’s Auto|biographical Fragments.” BSA Auto|biography Yearbook 6 (2013): 17–31. Print.

- —. In the Fold between Power and Desire: Women Artists' Narratives. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010. Print.

- —. “Love, Narratives, Politics: Encounters between Hannah Arendt and Rosa Luxemburg.” Theory, Culture & Society 30.1 (2013): 35–56. Print.

- —. “Ordinary|Extraordinary: Narratives, Politics, History.” Open Democracy. Open Democracy, 7 Dec. 2012. Web. 28 Jan. 2014.

- —. “Writing Feminist Genealogies.” Journal of Gender Studies 12.1 (2003): 5–19. Print.

- West, Shearer. Portraiture. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. Print.

- Young, Iris. Marion. ‘House and Home: Feminist Variations on a theme.’ Feminist Interpretations of Martin Heidegger. Eds. Nancy, J. Holland and Patricia, J. Huntington. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania University Press, 2001. 252–88. Print.