Abstract

In this article, the author explores the presence of photography in Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes and Claude Cahun’s Disavowals, or Cancelled Confessions. Published almost half a century apart, Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes and Disavowals foreground the traffic between verbal and visual self-representation in making lives and selves visible. In both texts, photography is central to the authors’ construction of the self: not only through the inclusion of photographic images of the author, but also through a photographic consciousness that pervades their writing. Kim considers how family photographs, both inherited and reconstituted, play a central role in the authors’ quest for autobiographical revisioning.

In Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography, Linda Haverty Rugg asks: “Did the invention of photography transform the way we picture ourselves?” (1). Like Rugg, I am interested in tracing “the transformation of an author’s self-image and self-writing when confronted with photographs of the self” (1). In this essay, I shall explore the presence of photographic images of the author in two autobiographies: Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes (hereafter, Barthes by Barthes) and Claude Cahun’s Disavowals, or Cancelled Confessions. Published almost half a century apart, Barthes by Barthes and Disavowals foreground the traffic between verbal and visual self-representation in making lives and selves visible. In both texts, photography is central to the authors’ construction of the self: not only through the inclusion of photographic images of the author, but also through a photographic consciousness that pervades their writing. Indeed, both autobiographies begin with a verbal account of photography—of looking at childhood photographs of himself (Barthes) and of posing for a portrait (Cahun). Paraphrasing the title of Timothy Dow Adams’ study on photography and autobiography, these two opening scenes offer an occasion for revisioning the self, and for thinking about life writing as light writing.

Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes

Although published before Camera Lucida, Barthes by Barthes has received considerably less attention in discussions about Barthes’s theorizing of photography. And yet photography, especially pictures of the author and his family, is a central preoccupation of Barthes’s autobiography. Barthes by Barthes betrays many of the concerns that Barthes will return to in his final book. In Camera Lucida, Barthes affirms the affective power of photography, and its relationship to mourning and memory. This turns around his discovery, shortly after his mother’s death, of a photograph of her as a child: “There I was, alone in the apartment where she had died, looking at these pictures of my mother, one by one, under the lamp, gradually moving back in time with her, looking for the truth of the face I had loved. And I found it” (67). The “Winter Garden Photograph,” as Barthes calls it, is famously never reproduced in the book, although many other photographs are; for Barthes, “[i]t exists only for me. For you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture, one of the thousand manifestations of the ‘ordinary’” (73). In Family Frames: Photography, Narrative and Postmemory, Marianne Hirsch discusses the series of looks and relations that are engendered by Barthes’s discussion of his mother and the “Winter Garden Photograph”: “Multiple looks circulate in the photograph’s production, reading, and description: Roland’s mother, facing her parents as she is photographed, at the same ‘time’ faces her son who finds himself in her picture” (1–2). Hirsch foregrounds the “‘familial looks’ that both create and consolidate the familial relations among the individuals involved, fostering an unmistakable sense of mutual recognition” (2).

Shortly after his discussion of the “Winter Garden Photograph,” Barthes recounts an (apocryphal?) anecdote: “An unknown person has written me: ‘I hear you are preparing an album of family photographs’ (rumor’s extravagant progress). No: neither album nor family” (Camera Lucida 74). But Barthes had already prepared a family album of sorts for Barthes by Barthes, published five years before Camera Lucida and, crucially, while his mother was still alive. Barthes by Barthes begins with forty or so pages of photographs, mainly drawn from his own personal collection.Footnote1 Most are accompanied by captions, although these are not so much explanatory as ruminative; indeed, the list of illustrations at the end of the book, which provides dates, names, and locations, relieves the text proper from having to provide such factual information. The first photograph in Barthes’s autobiography is of his mother, taken circa 1932—of this photograph, which Barthes revisits at the beginning of Part Two of Camera Lucida, he observes that it is an image “which shows my mother as a young woman on a beach of Les Landes, and in which I ‘recognized’ her gait, her health, her glow—but not her face, which is too far away” (63). The inclusion of a family photograph album at the beginning of Barthes by Barthes might be read as a nod to the conventions of the genre, acquiescing to the curiosities of a readership that takes for granted the presence of photographs in biography and autobiography. Indeed, Nancy Pedri contends that: “the introductory photographic album entices readers to look for authenticating traces of Roland Barthes’s narrating subject, despite all warnings against such a quest” (165). The presence of family photographs—and the fact that they precede the main text—draws the reader in as an intimate, a confidant. Here, photography supports and augments autobiography’s claims to intimacy, familiarity, and revelation. Shirley Jordan proposes that intimacy is key to understanding the function of photography in autobiography: “As it explores the potential of telling through showing, visual autobiography plays with photography’s propensity to position us as intimates, privy to what only those closest to the autobiographical subject would normally see” (53). There are images of Barthes’s parents and grandparents, and of the author as a child, adolescent, and adult, as well as scenic shots of his ville natale, Bayonne, and his childhood home. But even in this gesture—which seems to satisfy one of the conventions of the autobiography—Barthes disrupts expectations by deviating from the usual chronological order. For example, the photographs of his grandparents come after we have seen pictures of Barthes as a young boy. If one of the functions of the family photograph is to make “appear what we never see in a real face (or in a face reflected in a mirror): a genetic feature, the fragment of oneself or of a relative which comes from some ancestor” (Camera Lucida 103), the formal structure of the photograph album—its lack of chronological order—nevertheless seems to resist the mythologizing of familial lineage. Under a family portrait of his grandfather as a young man, pictured with his parents and siblings, Barthes writes: “Final stasis of this lineage: my body. The line ends in a being pour rien” (Barthes by Barthes 19).

However, the inauguration of the self-representational strategies in Barthes by Barthes begins with photography in two ways: not only the family photograph album, but also through the author’s reflections on looking at photographs of himself: “To begin with, some images: they are the author’s treat to himself, for finishing his book. His pleasure is a matter of fascination (and thereby quite selfish). … And, as it happens, only the images of my youth fascinate me. Not an unhappy youth, thanks to the affection which surrounded me, but an awkward one, because of its solitude and material constraint. So it is not nostalgia for happy times which rivets me to these photographs but something more complicated” (3). Structurally, the text begins with photography (the family photograph album), but, as a beginning, it is already an ending: Barthes regards the images as a reward to himself for having completed writing his book. Thus, the images both precede and proceed the writing: the photographs pre-date the writing of the book and are placed before the main body of the text. However, if the author is to be believed, they also come after the writing of the book, as a “treat” and “pleasure” that follow the completion of the text. Crucially, this pivotal encounter between the narrator and his own photographic self-image engenders “a state of disturbing familiarity: I see the fissure in the subject (the very thing about which he can say nothing). It follows that the childhood photograph is both highly indiscreet (it is my body from underneath which is presented) and quite discreet (the photograph is not of ‘me’)” (3). In looking at photographs of himself, the narrator describes feelings of detachment and a failure of recognition: “When consideration... treats the image as a detached being, makes it the object of an immediate pleasure, it no longer has anything to do with the reflection, however oneiric, of an identity; it torments and enthralls itself with a vision which is not morphological (I never look like myself) but organic” (3). What is significant to note here, I think, is that Barthes can only begin his writing of the self through a reckoning with photographic images of himself.

Barthes returns to this experience of failing to recognize oneself toward the end of the photograph album section. On a right-hand page, there are two images of Barthes, both of him alone. The first, dated 1942, depicts a close-up of Barthes’s face against a solid black backdrop, his expression pensive, melancholy even. The second, underneath, is dated 1970 and shows Barthes at his desk, writing; the camera is positioned behind him, and the photograph is taken with his body half turned, as if he has momentarily turned away from his work. On the opposite page, Barthes writes: “‘But I never looked like that!’—How do you know? What is the ‘you’ you might or might not look like? Where do you find it—by which morphological or expressive calibration? Where is your authentic body? You are the only one who can never see yourself except as an image: you never see your eyes unless they are dulled by the gaze they rest upon the mirror or the lens (I am interested in seeing my eyes only when they look at you): even and especially for your own body, you are condemned to the repertoire of its images” (36).

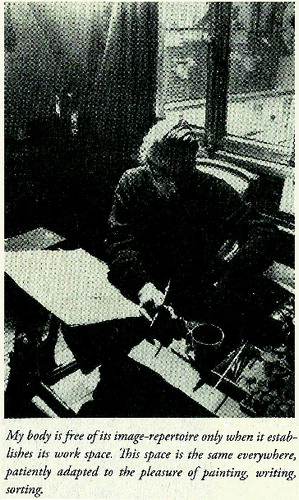

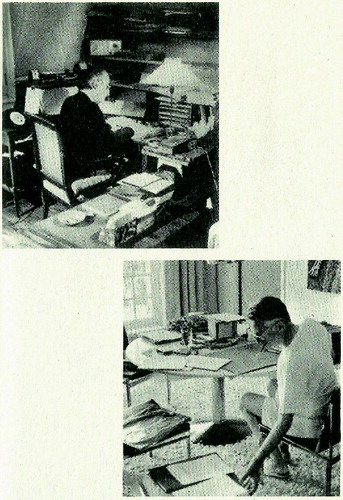

On the following two pages are three more photographs of Barthes working at his desk, taken from different angles (see ).

Unlike the preceding images, Barthes never meets the gaze of the lens, thus lending each image a candid, even naturalistic quality, as if each image was taken without the subject’s knowledge. In , the camera is positioned in front of Barthes, but so that it looks down on the author, who is seated behind his desk; Barthes himself is looking down, and thus averts the gaze of the camera. In , the photographs are taken from behind, so that the direct gaze of the subject is again nullified. The liberation of the author’s body can only occur through its engagement in labor, in particular the labor of writing: “My body is free of its image-repertoire only when it establishes its work space. This space is the same everywhere, patiently adapted to the pleasure of painting, writing, sorting” (38). Photography, or the “image-repertoire,” is an obstacle to writing: “So you will find here, mingled with the ‘family romance,’ only the figurations of the body’s prehistory—of that body making its way toward the labor and the pleasure of writing” (3). This preliminary photograph album, then, is something that Barthes sees as necessary to work through before writing. The autobiographical endeavor is imagined here as a confrontation between two technologies (or media) of self-representation: writing and photography.

Object Relations

However, it is not only the illustrative or representational qualities of the photograph that concern Barthes. He is also interested in their status as objects, and this understanding of the photograph as object is evident in the narrator’s opening account. In describing the photographs as “the author’s treat to himself, for finishing his book,” Barthes underlines their status as material objects, not just images. The photographs are imagined as a gift or a reward, but one where the author is both giver and recipient—a splitting of the self that is mirrored in the autobiographical project, in which the authorial subject is simultaneously the object of the writing. This is registered here, and throughout the rest of the book, in Barthes referring to himself in both the first and third person: he is both “I” and “he.” However, as Michael Sheringham cautions: “We must not imagine... that the ‘real’ Barthes is located behind the scenery... What matters about the pronouns is not some imaginary division between the aspects of Barthes but the effect of suddenly switching from one to the other, while talking about the same person” (195).

An important strand of recent critical scholarship on photography focuses attention on the photograph as object. In the introduction to the edited collection, Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images, Elizabeth Edwards and Janice Hart stress the materiality, not simply the illustrative qualities, of the photograph: “a photograph is a three-dimensional thing, not only a two-dimensional image. As such photographs exist materially in the world. … Photographs are both images and physical objects that exist in time and space and thus in social and cultural experience” (1).Footnote2 The objecthood of the photographs in Barthes’s family album is registered in the list of illustrations at the end of Barthes by Barthes. Each photograph is listed in order of page number, along with details of its subject(s), date, location, and provenance, if known—the kind of factual information that would often be jotted down on the back of a photograph. The organizing structure of the family album is thus revealed to be analogous to that of a museum catalog or archival inventory: name, place, year. Barthes states that: “I have kept only the images which enthral me, without my knowing why. … And, as it happens, only the images of my youth fascinate me” (3). The narrator’s experience of looking at these photographs of himself moves between pleasure, fascination, and enthrallment: “When consideration (with the etymological sense of seeing the stars together as a significant constellation) treats the image as a detached being, makes it the object of an immediate pleasure, it no longer has anything to do with the reflection, however oneiric, of an identity” (3). However, this pleasure in looking does not emerge from a sense of familiarity or self-recognition; rather, it comes from an experience of seeing himself as object.

The realization that one is drawn into a complex exchange of looks, in which the self is constituted as both subject and object, is critical to understanding family photographs, according to Hirsch: “Within the family, as I look I am always also looked at, seen, scrutinized, surveyed, monitored. Familial subjectivity is constructed relationally, and in these relations I am always both self and other(ed), both speaking and looking subject and spoken and looked at object: I am subjected and objectified” (9). Just as the family photograph participates in this economy of familial looks—indeed, is only made meaningful through its being drawn into this economy—I would propose that it also participates in another, interconnected economy: that of the familial object. The economy of the familial object is wedded to that of the familial looks that Hirsch proposes, and this economy is central to understanding Barthes’s relationship to photography in his autobiography.

Reflecting on Camera Lucida, W. J. T. Mitchell observes that: “Barthes is not a photographer; he made none of the photographs within his text. He therefore has no collaborator in the usual sense. His collaborator is ‘Photography’ itself, exemplified by an apparently miscellaneous collection of images, some private and personal” (306). Thus, Barthes is positioned as a collector; the photographs are images as well as possessions. But family photographs are special kinds of objects: not only can they be displayed in albums or on walls, but they can also be exchanged, passed on, inherited, and even destroyed—and, in the case of the “Winter Garden Photograph,” withheld. According to Hirsch: “As photography immobilizes the flow of family life into a series of snapshots, it perpetuates familial myths while seeming merely to record actual moments in family history” (7). Perhaps we can trace some of Barthes’s desire to rid himself of the family photograph album’s image-repertoire back to this codification and concretization of family life—the freezing and isolating of discrete moments, reconstituted into a coherent narrative. Barthes resists this narrativizing impulse, placing the photographs out of chronological order, and leaving the reader to speculate on the association between the juxtaposed images.

Claude Cahun’s Disavowals

Written almost half a century before Barthes by Barthes, Claude Cahun’s experimental memoir Disavowals explores the performative possibilities of self-representation in photography. Born Lucy Schwob, the author adopted the pseudonym Claude Cahun from her early twenties, and this interest in shifting names and personae would feature prominently in her artistic and literary endeavors. Originally published in French as Aveux non avenus, Disavowals was not published in English until 2007. It consists of ten chapters, each introduced with a photomontage of the author, created in collaboration with her stepsister and partner Suzanne Malherbe. Like Cahun, Malherbe assumed a pseudonym for her creative endeavors, taking on the equally non-gender-specific name Marcel Moore. Disavowals resists easy categorization, as Jennifer Mundy points out in her introduction to the English translation: its candid and intimate reflections on the narrator’s inner life lend weight to its autobiographical status, yet “it eschews conventional narrative and realism in favour of aphorisms and episodic interludes, and should perhaps be better seen as a series of ‘poem-essays and essay-poems’” (vii). Mundy borrows the terms “poem-essays” and “essay-poems” from Pierre Mac Orlan, who wrote the original preface for Aveux non avenus (which is included in the 2007 English translation). Yet in suggesting this classification of Cahun’s writing, Orlan nevertheless underlines the text’s autobiographical origins: “Ideas trace elegant parabolas to end in a tragic unfolding, exploding without a sound. I believe that each idea this author launches forms a trajectory parallel to that of her own life” (xxv). Poetry, essay, photography—Cahun marshals all of these forms in her autobiographical self-revisioning.

Cahun’s autobiographical project begins with a knowing acknowledgement of the genre’s literary antecedents. The confession was an early and seminal form of Western autobiography, with Augustine and Rousseau as the most notable examples. As Agnès L’Hermitte (who assisted with the text’s translation) observes, “the title itself sets the agenda” (xxii). Any generic or formal belonging to the confessional mode of autobiography is immediately annulled: “The impetus of the projected confession (aveu—confession) is instantly ‘contradicted’ by its negative qualification (non avenu—cancelled) marking failure, powerlessness, evasion” (xxii). Yet, the annulment of the author’s “confessions” might also be read, perhaps paradoxically, as an authenticating gesture, in a similar vein to that of the “unauthorized” biography—that is, as “illicit” confessions that have been cancelled not because they are untruthful, but because they exceed the permissible limits of the genre.

It is the interplay between intimacy and performance that animates my discussion of Cahun’s self-representational strategies. The intersection of the visual and the verbal is crucial to understanding Cahun’s ludic approach to autobiographical writing. The photomontages that appear at the beginning of each chapter evince a conceptualization of the self as fragmented, multiple, and unstable. Masquerade, costumes, role play, and disguise are recurrent motifs. Disavowals undertakes a revision of the confessional mode of autobiographical writing at the same time as the photomontages perform the author’s revisioning of self. I shall return to these performative aspects of Cahun’s photomontages later, but first I would like to consider how the opening chapter inaugurates the book’s concern with photography. Cahun writes, “The invisible adventure. The lens tracks the eyes, the mouth, the wrinkles skin deep. … the expression on the face is fierce, sometimes tragic. And then calm—a knowing calm, worked on, flashy. A professional smile—and voilà! The hand-held mirror reappears, and the rouge and eye shadow. A beat. Full stop. New paragraph. I‘ll start again” (1). The inaugural scene of the writing, then—as in Barthes by Barthes—is also a scene of photography: here, the narrator imagines having her photograph taken. It is not a candid, spontaneous snapshot, but one that is posed, contrived, and “worked on.” Certainly, this is how Mundy figures this opening scene in her introduction: Cahun “[i]magining herself posing for the camera” (xiii). But might there be a way of reading this scene with Cahun as photographer, rather than subject? Or, as Gen Doy suggests, Cahun as both photographer and subject: “Like a coated mirror, Cahun’s photographs, many produced in collaboration with her partner Malherbe|Moore, are sensitised surfaces where the location of the subject both ‘before’ and ‘behind’ the camera is interrogated” (6). This latter reading—of Cahun as the subject who looks and is looked at—accords with the necessary split and doubling of the autobiographical author, who simultaneously writes and is written about. Indeed, as Laura Marcus writes: “autobiography is able to secure, at one level at least, the much desired unity of the subject and object of knowledge” (5).

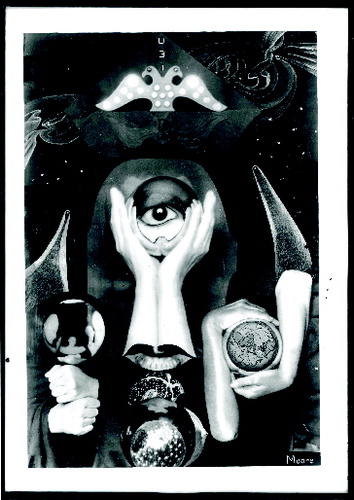

While for Barthes, this experience of the self as fractured and disconnected comes at the point of looking at photographs from his youth and not recognizing himself, for Cahun, this awareness emerges in the act of posing for and taking photographs. Crucially, this is imagined through the camera’s lens, which is an active agent in the objectifying of the photographic subject as it “tracks the eyes, the mouth, the wrinkles skin deep.” The camera not only captures a moment, but is also a tool for surveillance, monitoring the subject’s movements. Moreover, and perhaps more importantly for Cahun’s self-portraits, the camera lens fragments the subject’s body, reducing it to discrete, discontinuous body parts: eyes, mouth, skin. Bodily fragmentation is a recurrent motif in the photomontages; Cahun’s face and body are dissected and reconstituted, often transformed into an unrecognizable object. This is evident from the first photomontage, the text’s frontispiece ().

In the center is an orb containing an eye cupped by two hands that sit atop a set of rouged lips. Beneath this are overlapping spherical objects, such as a pomegranate, sliced open to reveal its glistening seeds. To the left is another orb, this time a convex mirror with multiple distorted images of a bald-headed Cahun. The multiplication of Cahun’s image—distorted, fragmented—has the effect of destabilizing Cahun’s identity: “Individualism? Narcissism? Certainly. My best characteristic, the one and only intentional fidelity I am capable of. You don’t care? I'm lying anyway: I scatter myself too widely for that” (Disavowals 9). There is no singular self-portrait to capture the distilled essence of the author|artist, but a proliferation of selves: identity is not so much revealed as it is performed, assumed, and accumulated. Cahun actively plays with the codes of gender and sexual identities, shifting abruptly between feminine and masculine modes of dress, and often embracing an androgynous self-image.

In the fourth chapter, “C. M. C. (Vanity, Sex),” Cahun returns to a consideration of the fragmented body, reduced to mere facial features and body parts: “Redundant breasts; irregular, ineffectual teeth; eyes and hair of the blandest colour; hands delicate enough but twisted, deformed. The oval head of a slave; forehead too high... or too low; a nose fashioned well enough of its type—a hideous type; the mouth, too sensual... She consents to recognise herself. And the illusion she creates for herself extends to a few others” (50). Although there is no specific mention of photography in this passage, the matter-of-fact dissection of the subject’s body echoes the earlier description of the photographed subject. The impersonal listing and assessment of the portrait subject’s appearance, in which her features are rendered as disconnected objects, is suggestive of the camera lens’s ability to zoom in on a part of a whole. Therese Lichtenstein reads the “fragmented body parts arranged totemically like rebuses that form no coherent whole” in relation to the “Exquisite Corpse” parlor game that was invented by the surrealists, “in which different artists would each write a phrase, or draw an image, to construct a composite sentence or drawing, the overall form of which they would grasp only when the work was completed” (94). While Cahun was on the fringes of the male-dominated surrealist circle—she was a friend of André Breton and his wife Jacqueline Lamba—her work was largely excluded from the surrealist canon until the 1980s. Nevertheless, her photomontages are clearly in sympathy with the surrealist aesthetic of contingency, fragmentation, surprise, and unexpected associations: “As is always the case in Claude’s world, nothing is simple, everything is mingled in a deliberate and fearful confusion, mangling as well as mingling” (Caws 137).

Photographic self-portraits occupy such a central place in Cahun’s autobiographical text because they afford her license to reinvent her own self-image. It is not so much photography’s claims (however contested) to verisimilitude and referentiality that Cahun seeks to enlist; rather, it is the medium’s capacity to capture and document multiple iterations and performances of the self. The dynamic process of photographic self-portraiture is emphasized, as the opening scene makes clear. Cahun foregrounds the production of the photographic image: the posing for the camera, the application of make-up, the self-conscious look in the mirror. While the interrogation of the photographic self-image in Barthes by Barthes often turns around a failure of self-recognition, in Disavowals, it is precisely photography’s capacity to distort and manipulate self-images that is embraced. The narrator writes, “indiscreet and brutal, I enjoy looking at what’s underneath the crossed-out bits of my soul. Ill-advised intentions have been revised there, become dormant; others have materialised in their place” (6).

As I suggested earlier, photographs in autobiography often promise an intimate revelation, especially if they are drawn from private or family collections, which are usually outside of the public domain. But Cahun’s self-portraits divert the reader|viewer’s curious gaze, revealing instead a series of masked, costumed, and disguised selves. In the photomontage for the ninth chapter, “I .O. U,” Cahun declares, in her own handwriting, “under this mask another mask. I will never be done taking off all these faces” (183). These words wind their way around a composite portrait of Cahun, consisting of two columns of overlapping faces—all Cahun, but some masked—sprouting from a single neck. Beneath each face lies another, a seemingly endless proliferation of selves.

Nevertheless, the narrator in Disavowals does express some hesitations about this process of continual reinvention: “No point in making myself comfortable. The abstraction, the dream, are as limited for me as the concrete and the real. What to do? Show a part of it only, in a narrow mirror, as if it were the whole?... Until I see everything clearly, I want to hunt myself down, struggle with myself. Who, feeling armed against her own self, be that with the vainest of words, would not do her very best if only to hit the void bang in the middle. It’s false. It’s very little. But it trains the eye” (1). Lichtenstein detects a certain weariness in Cahun’s constant, and often abrupt, shifts in personae: “a sad feeling of a soul wandering in limbo from one mask to another. Is this sexually indeterminate presence a liberated self or a self in crisis?” (94). Cahun herself seems to register this feeling when she writes: “We cover our faces with masks then cover them again, put on make-up, then make them up again, maybe only exaggerating the resemblance to, only accentuating the imperfections of, the hidden face. … it's a waste of time” (118).

For Cahun, photographic self-representation sponsors a ceaseless reinvention of the self. Here, the production and circulation of photographic images is co-opted into a dynamic process of role-playing and self-reinvention: each self-portrait is an opportunity to assume or appropriate another identity, another persona. Cahun is less interested in photography’s capacity for freezing a moment in time than she is in the possibilities of the medium to capture multiple iterations of the self. We are accustomed to thinking of a photograph as something that freezes a moment in time—that one can never replicate or to that one can never return—and while this might be true of the image itself, it is not accurately reflective of how photographs are used in Cahun’s photomontages. While each individual image represents a moment in time—fixed—the reuse and recontextualization of these self-images—dissected, enlarged, reduced, repeated—works against the immobility of the photographic images. The images themselves become mobile and mutable. Indeed, this is registered in the opening scene, when Cahun writes, “[a] beat. Full stop. New paragraph. I'll start again” (1). That moment in time may never be recovered, but, for Cahun, this is of little concern; one can always “start again.”

Cahun’s writing and photographic project—both in the apparent service of autobiographical revelation—are conceived of through the theatrical processes of scripting, staging, rehearsing, and performing. The opening scene, as I have already suggested, can be read as both an account of taking a photograph and being photographed. However, it can also be read metatextually as a performance, scripted by Cahun. The narrator dictates this scene, as if writing a scene in a play or film: “A beat. Full stop. New paragraph. I'll start again.” In a screenplay, “beat” is a term used to denote a pause in dialogue; here, it is followed by the instruction for a “[f]ull stop” and a “[n]ew paragraph,” suggesting the end of a scene.Footnote3 The description of posing for and taking a photograph is quite literally a scene being dictated by the narrator, with the beat representing a pause or shift in the timing of movement or action. Later, Cahun makes explicit the performative theatricality of her project. Like a director of a play, Cahun encourages a dynamic, continuing process of assuming different characters and personae: “I provide the theatre, you choose your stage sets, your adventures, your character, your sex, your make-up” (127). Writing, like photography, is about the envisioning—but not necessarily the fixing or concretizing—of a particular image, moment, or feeling; there is always the possibility of starting over.

Even as objects in and of themselves, the photomontages betray a sense of contingency. In the collaborative production of these artworks, Cahun and Moore draw on the vast repertoire of images of Cahun that had been created in the decade preceding the book’s publication. As Abigail Solomon-Godeau observes: “by the end of the 1920s Cahun had accumulated a virtual image bank of self-representations that she regularly circulated and recirculated within her own work. … self-portraits made in the 1920s (usually, the head or face alone) feature often in the photocollages produced with [Suzanne] Malherbe, ten of which were reproduced in Aveux non avenus in 1930” (117). Evoking a double metaphor of horticultural insertion and surgical transplantation, Lichtenstein describes this process of “recycl[ing] the same photographs in different photomontages, or crop[ping] photographs she has used elsewhere as single images and recombin[ing] them” as “a kind of random graft” (94).

Cahun’s incessant revisioning of her own self-image is, perhaps, the central preoccupation of Disavowals. The text traces a process of identity negotiation, in which different masks and personae are assumed and discarded. The multiplication of Cahun’s self-image suggests a narcissistic impulse. However, the effect of the proliferation of selves actually works against the reification of a stable, unified self. Given the self-centeredness that lies at the heart of autobiographical writing, it is not entirely surprising that Cahun draws attention to the narcissistic impulse here. But she remains suspicious of it, envisioning it as a kind of madness: “Self-Love. A hand grips a mirror—a mouth, nostrils palpitating—between swooning eyelids, the mad fixity of dilated pupils” (Disavowals 32). Indeed, her highlighting of the narcissistic impulse of autobiographical representation—whether in writing or photography—might also be read as a critique of the narcissistic motivations of self-representation. “Now would be the moment to fix the image in time as it is in space,” writes Cahun, “to seize completed movements—surprise oneself from behind. ‘Mirror’, ‘fix’, these are words that have no place here. In fact what troubles Narcissus the voyeur most is insufficiency, when his own gaze is interrupted” (33). It is self-fixation, perhaps, but not a fixing of the self.

Unlike the images in Barthes’s photograph album, the self-portraits that circulate in Cahun’s photomontages do not readily lend themselves to the category of family photographs. While the photomontage for the first chapter, “R. C. S. (Fear),” does feature an image of Cahun as a young girl (circa 1900, when Cahun would have been about six years old), most of the images of Cahun lack the naturalistic quality so often associated with family photographs. Here, the artist as a young girl appears not as “herself,” but in costume, dressed as Pierrot, the stock character of the sad clown that is well known from pantomime. One of the main obstacles in reading Cahun’s self-portraits as family photographs is the lack of context: there are no group portraits, and the close cropping of her face and torso (leaving sometimes only a hand or leg or eye) leaves little by way of identifying background information about locations or dates. In their insistence on stripping away this contextual detail, Cahun appears almost sui generis: liberated from the familial frame, she is free to negotiate her self-image unbound from considerations of genealogical lineage and resemblance. Indeed, in their privileging of theatrical role playing, artifice, and masquerade, these images of Cahun seem far removed from the group portraits or informal snapshots that one might expect to see in a family photograph album. Of course, all photographs, including family photographs, are staged to some extent; even a candid image, in which the subject is unaware that a photograph is being taken, is always framed by the photographer. While the seductive appeal of family photographs might be traced to their naturalistic aura of authenticity, such images are nevertheless governed by invisibilized codes of posing, looking, and framing: “The conventions of family photography, with its mutuality of confirming looks that construct a set of familial roles and hierarchies, reinforce the power of the notion of ‘family’” (Hirsch 47). Indeed, according to Hirsch: “If one instrument helped construct and perpetuate the ideology which links the notion of universal humanity to the idea of familiality, it is the camera and its by-products, the photographic image and the family album” (48). However, reading against the conventional framing of family photographs, how might these self-portraits of Cahun, made in collaboration with Marcel Moore, compel a rethinking of the limits of this category? After all, as artistic collaborations between Cahun and Moore, these images are, in a literal sense, family portraits, staged, directed, and posed for by Cahun, with Moore—stepsister, lover, and lifelong companion—often as the camera operator.Footnote4 If we take seriously “the power of photography as a technology of personal and familial memory” (193), then how might we read Cahun’s photomontages as intervening in the structures and ideologies that underpin how we define and understand family structures?

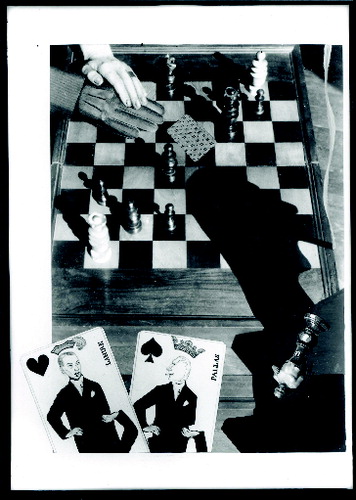

The photomontage that comes closest to representing an alternative domestic familial scene appears at the beginning of chapter four, “X. Y. Z. (Lying)” ().

It depicts a game of chess between two barely visible opponents. On the top left-hand side, a pair of hands, one gloved and one bare, rests on the chessboard. In the foreground are two playing cards—the jack of hearts and the queen of spades. The jack and queen exchange knowing glances, and both are androgynous figures, dressed in men’s dinner suits with close-cropped hair. The shadow of an androgynous figure in profile smoking a cigarette, which bears a striking resemblance to the queen of spades, is cast over the bottom right-hand corner of the chessboard. The jack-of-hearts card juts out of the left-hand edge, breaching the rectangular frame of the image; the pair of cards is within the frame of the photomontage but also exceeds its boundaries. It is an apposite visual metaphor, then, for Cahun and Moore’s relationship: an intimate bond that is both intra- and extra-familial, within and outside the family frame. Cahun and Moore’s lesbianism and their uncommonly close, even symbiotic, relationship (both lovers and stepsisters) set them outside of the conventional family structure.Footnote5 While neither candid snapshots nor formal portraits, these images can, I would argue, be read as alternative family photographs. In reading them so, however, it is not only the aesthetics and codes of family photography that are called into question, but also the construction of the family unit itself. Like Barthes, Cahun resists the reificatory potential of family portraiture—that is, its capacity to define and naturalize familial relations. Unlike Barthes, however, Cahun sees in photography the possibility of revisioning and reimagining an alternative family structure.

Final Revisions

In the opening photograph-album section of Barthes by Barthes, Barthes claims that “[o]nce I produce, once I write, it is the Text itself which (fortunately) dispossesses me of my narrative continuity” (4), establishing that his autobiography will not be beholden to the conventions of linear narrative development. In his desire to move beyond narrative continuity, he turns to the alphabet to create order: “Temptation of the alphabet: to adopt the succession of letters in order to link fragments is to fall back on what constitutes the glory of language… . The alphabet is euphoric: no more anguish of ‘schema,’ no more rhetoric of ‘development.’ … an idea per fragment, a fragment per idea” (147). For Barthes, “[t]he alphabetical order erases every origin. Perhaps in places, certain fragments seem to follow one another by some affinity; but the important thing is that these little networks not be connected, that they not slide into a single enormous network which would be the structure of the book, its meaning” (148). The privileging of the fragment and the largely alphabetical structure of Barthes’s autobiography sponsors a working through of ideas, allowing him to think through an idea without necessarily committing himself to it—“to keep a meaning from ‘taking’” (148). As Marcus observes: “the ostensibly narrative element is provided by photographs,” while “the ‘text’ takes the form of fragmented explications of images, concepts, words, memories” (217). This alphabetical “antistructure, its obscure and irrational polygraphy” (148), represents for Barthes a liberation not only from narrative continuity, but also from the image-repertoire of the family photograph album: “The image-repertoire will therefore be closed at the onset of productive life... Another repertoire will then be constituted: that of writing” (4). The narrator states that he wishes to escape from the framing devices of photography. Barthes places the family photograph album at the beginning of his autobiography so that his writing might proceed free from its image-repertoire. Barthes sees in writing a capacity for revisioning the self that, for him at least, does not exist in photography. For Barthes, writing is preferable to photography because writing can always be corrected, revised, and amended. After all, the two textual forms that are most commonly subject to alphabetical ordering—the dictionary and the encyclopedia—invite revision, correction, and annotation. Even in their pretence to comprehensiveness, both the dictionary and the encyclopedia are always incomplete; that each volume will be revised, superseded, and perhaps even rendered obsolete is its predetermined destiny.Footnote6

In Barthes by Barthes, writing supersedes photography, but remains vulnerable to its return. For writing “to be displayed (as is the intention of this book) without ever being hampered, validated, justified by the representation of an individual with a private life and a civil status, for that repertoire to be free of its own, never figurative signs, the text will follow without images, except for those of the hand that writes” (4). Yet Barthes can never completely free his writing from photography. Barthes by Barthes itself is bookended by two facsimiles of his own handwriting, in the paratextual space of the book. The first famously declares: “It must all be considered as if spoken by a character in a novel.” At the end, Barthes writes: “And afterward? What to write now? Can you still write anything? One writes with one’s desire, and I am not through desiring.” Here is image as text and text as image, enjoined through the photographic reproduction of Barthes’s own handwriting. And perhaps it is here that the imbrication of the verbal and the visual in revisioning one’s self is made explicit. It is a trace of the author’s body—not of the body as referent, but rather the trace produced by the author’s body, a final substitution of corpus for corps.

In this restless movement from one idea to another, we might detect an affinity with Cahun’s adoption of different guises in her self-portraits. Cahun does not share Barthes’s anxiety to rid himself of the image-repertoire. She sees in photography the potential to constantly revision herself. As both artist and subject, Cahun exercises control over her photographic self-representation: her revisioning of her own self-image is made possible through dissecting, fragmenting, and recontextualizing her self-portraits. Cahun remains hopeful for the revisionist and improvisatory possibilities of photographic portraiture: “But why hasten towards eternal conclusions? It behoves death, not sleep (another trompe-l'oeil), to conclude. Life’s role is to leave me uncompleted, allow me only freeze frames. Start again. Connections, repairs, reiterations, incoherence, so what! Provided that something else continually comes along” (Disavowals 202). Ultimately, Barthes desires his liberation from photography’s image-repertoire and Cahun seeks her liberation within it.

Notes

1. In the original French publication, Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes, Barthes states in the list of illustrations at the end of the text: “Sauf mention particulière, les documents appartiennent à l'auteur” (“Unless otherwise stated, the documents [images] belong to the author.” All translations mine.)

2. Indeed, it is a reflection on the oft-discussed scene from Camera Lucida in which Barthes is looking through old family photographs on the occasion of his mother’s death that opens Edwards and Hart’s introduction.

3. “New paragraph” is a translation of the French word alinea, which can also be translated into English as “paragraph mark,” “paragraph sign,” or “pilcrow,” which is the typographical symbol for a new paragraph.

4. Cahun and Moore collaborated on the photomontages that appear in Disavowals, and Moore’s name is clearly signed in some of them. For a detailed analysis of Cahun’s photographic technique and Moore’s central role, see Stevenson.

5. Mary Ann Caws writes: “In 1909 Lucy Schwob [Cahun] returned to school in Nantes, and fell in love with Suzanne Malherbe [Moore]... Their families were friends, and upon the death of Lucy’s mother, her father, Maurice Schwob, married Suzanne’s mother” (127).

6. In chapter one of Poetics of the Literary Self-Portrait, Michel Beaujour discusses Barthes by Barthes in relation to the speculum, or medieval encyclopedia.

Works Cited

- Adams, Timothy Dow. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000. Print.

- Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. 1981. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill, 2000. Print.

- —. Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes. 1975. Trans. Richard Howard. New York: Hill, 2010. Print.

- —. Roland Barthes par Roland Barthes. Paris: Seuil, 1975. Print.

- Beaujour, Michel. Poetics of the Literary Self-Portrait. Trans. Yara Milos. New York: New York UP, 1991. Print.

- Cahun, Claude. Aveux non avenus. 1930. Paris: Mille et Une Nuits, 2011. Print.

- —. Disavowals, or Cancelled Confessions. Trans. Susan de Muth. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology P, 2008. Print.

- Caws, Mary Ann. Glorious Eccentrics: Modernist Women Painting and Writing. New York: Palgrave, 2006. Print.

- Doy, Gen. Claude Cahun: A Sensual Politics of Photography. London: Tauris, 2007. Print.

- Edwards, Elizabeth, and Janice Hart, eds. Photographs Objects Histories: On the Materiality of Images. London: Routledge, 2004. Print.

- Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1997. Print.

- Jordan, Shirley. “Chronicles of Intimacy: Photography in Autobiographical Projects.” Textual and Visual Selves: Photography, Film, and Comic Art in French Autobiography. Ed. Natalie Edwards et al. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2011. 51–77. Print.

- L'Hermitte, Agnès. “Postscript: Some Brief Observations.” Cahun, Disavowals vii–xvii. Print.

- Lichtenstein, Therese. “A Mutable Mirror: Claude Cahun.” Illuminations: Women Writing on Photography from the 1850s to the Present. Ed. Liz Heron and Val Williams. London: Tauris, 1996. 91–95. Print.

- Marcus, Laura. Auto|Biographical Discourses: Criticism, Theory, Practice. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1994. Print.

- Mundy, Jennifer. Introduction. Cahun, Disavowals vii–xvii. Print.

- Orlan, Pierre Mac. Preface. Cahun, Disavowals xxiv–xxvi. Print.

- Pedri, Nancy. “Documenting the Fictions of Reality.” Poetics Today 29.1 (2008): 155–73. Print.

- Rugg, Linda Haverty. Picturing Ourselves: Photography and Autobiography. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1997. Print.

- Sheringham, Michael. French Autobiography: Devices and Desires: Rousseau to Perec. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1993. Print.

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. “The Equivocal ‘I’: Claude Cahun as Lesbian Subject.” Inverted Odysseys: Claude Cahun, Maya Deren, Cindy Sherman. Ed. Shelley Rice. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology P, 1999. 110–25. Print.

- Stevenson, James. “Claude Cahun: An Analysis of Her Photographic Technique.” Don’t Kiss Me: The Art of Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. Ed. Louise Downey. New York: Aperture Foundation, 2006. 46–55. Print.