Abstract

Three best-selling “animalographies”—Jon Katz’s Soul of a Dog, Susan Orlean’s Rin Tin Tin, and Alexandra Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog—do not exemplify critical posthumanism, which articulates the multidimensional animal–human nexus, nor the genre of “new biography,” but textually and visually re-enact ideological frameworks of spiritualism, commodification, and scientism.

On a warm summer day not long ago, I walked into a Barnes and Noble bookstore in Evanston, Illinois, and was assaulted by the sights and smells of bookish humanity: huge banners of authors hung from the ceiling; shoes squeaked on the floor; a soft hubbub of voices drifted from the busy cash registers; and the sweet, nutty smell of Starbucks permeated everything. There were tables groaning with biographies of famous and notorious people; tables chronicling human history and knowledge; and tables piled with self-help books claiming to solve weight gain, memory loss, poor income, and other ills. People bumped elbows and studied the people around them, and read about every aspect of human experience. But smack dab in the middle of the floor was a huge, eye-catchingly arranged display of books about dogs, including the three that I discuss here: Jon Katz’s Soul of a Dog: Reflections on the Spirits of the Animals of Bedlam Farm, Susan Orlean’s Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, and Alexandra Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know.

Dogs have increasingly become big business in the US, as evidenced by books about them framing the entrance to the US’s major bricks-and-mortar bookseller. Too, their commodification as pets is well established, given the increasing number of lines of designer clothes, specialized diets, and soft toys all manufactured to lure dog owners to treat their canines more and more as children. But, with that explosion in consumer goods allegedly designed for canine consumption, there has been an equal explosion in books about dogs, including ones that supposedly help us understand canine subjectivity. This has occurred simultaneously with the memoir boom, itself an event begging explanation by life-writing|narrative scholars who see the twenty-first century as the age of the memoir (see Smith and Watson 127–65; Miller).

This article aims to consider the current ideological frames of canine memoirs, but to complicate their framing by selecting three books that combine textual and visual referents. Life-writing scholarship has enjoyed an increasing turn to the visual as what constitutes life writing|narrative has expanded to include all things autobiographically scopophilic, so that the kinds of art explored by life-writing|narrative scholars include photography and the graphic, both of which feature prominently in canine memoirs (see Adams; Hirsch; Chute). The texts I consider are neither artistic creations, nor are they meant to be; nonetheless, the visuals they include are an integral part of their textual effect. Thus, I am interested in reading the visuals in them within the context of visual-rhetoric scholarship, just as I am interested in reading canine memoirs combining the written and visual within the contexts of animal studies, posthumanism, cultural studies, and life-writing|narrative studies.

Because the three canine memoirs I discuss combine the visual and textual under the ideological sign of “dog,” they are especially important for examining issues that are crucial to life-writing|narrative studies: what constitutes bios and what constitutes graphe. As the root word bios suggests, and as Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson have asserted, the bios|life of autobiography “include[s] how one has become who he or she is at a given moment in an ongoing process of reflection” (1). The life depicted, in other words, generates a subjectivity through a reflective process—a definition that is grounded in autobiography’s Enlightenment origins. Life-writing|narrative studies has traditionally been humanistic in its origins because the term autobiography, its practice, and most theorizing about it have centered on the human, even while what constituted human expanded to include marginalized subjects as critics used the theoretical lenses of post-structuralism, feminism, and post-colonialism, among other approaches, to interrogate who counts as human. In a departure from focusing exclusively on the human subject and as a gesture toward bringing to bear theoretical questions posed by posthumanism on life-writing|narrative studies, some scholars have recently begun to explore the meaning of “subject” more fully (see Whitlock and Couser). The impetus of posthumanism as a theoretical construct crosses boundaries of subjectivity in new ways, questioning how we have constructed the human by theorizing the lived connections between human and non-human, human and machine, and non-human and machine. These connections are at the heart of posthumanism, which challenges the long-standing philosophical and religious cordoning off of human beings from the rest of the animal kingdom; and it is equally pertinent to life-writing studies, which centers on subjectivity, memory, and experience, among other concerns. Posthumanism is not a monolith, and I want to make the distinction, first put forward by Bart Simon in a 2003 introduction to a special issue of Cultural Critique, between popular posthumanism, which poses as the union between human and machine and animal, and critical posthumanism, which methodologically assumes that human subjectivity is one of only many subjectivities. The concomitant radical destabilizing of human subjectivity posited by critical posthumanism pointedly asks what it means to be a subject; this is where canine memoirs, which are obviously written by human beings but have as their subject dogs, provide one litmus test for talking about what we mean by bios in life-writing|narrative studies.

Graphe, or writing, is also contested by canine memoirs, not only because the writing in these texts is meant to tell the stories of canines rather than human beings, but also because graphe becomes a much thicker and more contested term when canine memoir combines written and visual elements. Like posthumanism, visual rhetoric is a vibrant and growing field of inquiry, encompassing cultural studies, semiotics, and art history, among other disciplines, so that concentrating on multimodal canine memoirs troubles the graphe in autobiography studies to reveal many reading strategies that may or may not work in tandem. Reading images contests the hegemony of the narrative voice, a lynchpin of the humanist subject. The exposition of cultural context we might find in a textual narrative is complemented and challenged by the affective representation of cultural context in images, a presentation of context that readers must unpack themselves. Writing about the rhetoric of images in hypertexts, Mary E. Hocks notes that “readers experience a dissonance” when confronted with works that are grounded in both text and images, “that defamiliarizes their experiences with print narrative [and] argumentative forms” (641). That defamiliarization irrupts the binary logic of the humanist subject and the life-writing text (on which Lejeune’s “autobiographical pact” is grounded), and “uncover[s] … the free play of the signifier,” as visual rhetorician Irit Rogoff asserts, to enact “a freedom to understand meaning in relation to images, sounds, or spaces not necessarily perceived to operate in a direct, causal, or epistemic relation” (382).Footnote1

Posthumanism and animal studies challenge our conventional wisdom about bios and the solidity of the humanist subject; visual rhetoric troubles our thinking about how a text makes meaning. The upshot is that a much richer reading strategy is called for, one that is sensitive to the presumptions of humanist-centric subjectivity and to the increasing visualization of cultural signs. This article, then, explores sign-making under the highly contested sign of dog in an effort to unravel how the visual and verbal combine with|contradict one another in ways that productively help us interrogate bios and graphe, as both are perhaps tenuously joined.

Among the hodgepodge of books on that retail table, the three New York Times best-sellers I have selected perform human and canine bios, verbal and visual graphe, ideology and epistemology, and cultural production. Katz’s Soul of a Dog: Reflections on the Spirits of the Animals of Bedlam Farm is an excellent example of how dogs as a companion species are “framed” by various ideologies. The bulk of Katz’s book is about dogs, especially his Border collie, Rose, who exemplifies a “natural” working subject; Rose is likewise framed by a long tradition of philosophical inquiry into whether animals have souls—hence the book’s title, denoting a meditation on what, if anything, distinguishes humans from non-human animals. In Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know, Horowitz quite clearly speaks to an urban audience, for whom her expertise as a canine researcher gives her the cachet to explain the Umwelt, or environment, of dogs as a species, while in Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend, Orlean, a staff writer for the New Yorker since the 1990s, traces Rin Tin Tin as a living canine and screen and marketing success to recreate historically a changing US. Significant about all three texts is each author’s choice to interweave his or her story with their respective canine subjects. Soul of a Dog purportedly centers on Rose, but the reader also learns about Katz’s failed marriage and his desire to leave the city for the “naturalness” of the country. Rin Tin Tin is likewise human autobiography, for we learn of Orlean’s relatives perishing in concentration camps and her childhood desire to be allowed to touch the plastic Rin Tin Tin statue her grandfather kept on his desk blotter. Inside of a Dog is a scientific explanation of the subtitle’s announcement What Dogs See, Smell, and Know, but it is also Horowitz reminiscing about her life with her dog Pumpernickel. The visual rhetoric of these three texts is equally complex and functions at three different mimetic levels. Soul of a Dog and Rin Tin Tin use photographs to depict their canine subjects, frequently through the intimacy of a head shot, sometimes via interaction between human and canine, and once, rather abstractly, through shooting a Rin Tin Tin plastic representation. In keeping with the scientific emphasis of Inside of a Dog, there are no photographs between the book’s covers; rather there is a series of boldly executed line drawings.

My last paragraph asserts that contemporary canine memoirs are as much about the author as about a dog subject. This suggests the importance of subjectivity (Whose?) as a performance and an ethical issue. Crucial is whether the inclusion of the author’s story in a text purportedly about dogs is a cover-up for another agenda and|or whether it functions as “new biography,” biographical texts that “shuttle between the fictive and autobiographical” (Smith and Watson 8). The impetus of this new form was not simply to interpret present, historical documents, and to try to reconstruct the personality and psychology of the subject; the German biographer Emil Ludwig referred to his task as the “discovery of a human soul,” which is reminiscent, of course, of Soul of a Dog. (qtd. in Hoberman 650). The goal of new biography, in short, was to excavate a human subjectivity. New biography, as life-writing studies has defined it, represents a blending of human narratives and human subjectivities.Footnote2 The question, then, is whether currently popular animalographies are tethered by frameworks that fail to tell and picture dogs’ lives in a way that adequately or fairly represents canines, presuming that dogs’ subjectivity can be represented in print. Or, to put it another way, are the narratives and images so ideologically loaded that these animalographies act largely as vehicles to further an author’s hobby horse (no pun intended)?

The way in which these books visually and verbally represent both human and canine subjectivity is crucial: is there a symbiosis of subjectivities or does the human colonize the canine? In order to test this, I will invoke Donna Haraway’s use of genealogies in When Species Meet to capture how companion species touch each other. Haraway is famous for telling histories and family stories of species—machine, human and non-human animal—in an effort to communicate the tangled relating of different species in what Cynthia Huff and Joel Haefner have elsewhere described as the closest prose narrative can come to “posthumanist posthumanism,” as Cary Wolfe defines it (126), and what Simon would identify as critical posthumanism. Haraway’s genealogical methodology exposes ideological bedrock and its fault lines, and in the animalographies under discussion here, those fault lines include subjectivity, memory, and experience. G. Thomas Couser, while endorsing the recent explosion of conventional pet memoirs, claims that, “Even while such tame pet memoirs are hardly posthumanist, they do extend the notion of relational life writing to include our important relationships with animals” (192). Instead, I argue that posthumanism (and Haraway’s methodology, which she labels “not-humanism”) questions the idea of what Couser calls “relational life writing,” since the latter cannot capture the tangled webs of the relating between canine and human; a verbal|visual text reflecting the persistent skeins between dog and human would be, indeed, an innovative, new “new biography.”

Both Soul of a Dog and Rin Tin Tin appear at first glance to fit, at least loosely, the definition of new biography, for each text places the dog subject’s biography alongside the author’s autobiography, weaving back and forth between the two narratives to show effect. In Soul of a Dog, Katz does this straightforwardly by telling his memories of different companion species at Bedlam Farm in a style best described as dramatic musing. A case in point is Katz relating how Rose retrieves a ewe about to lamb during a movie shoot at Bedlam Farm: “Now time became critical. Within half an hour or so after the water breaks a lamb can die, and so can the ewe. ‘Rose, get the sheep,’ I said quietly. She had an uncanny ability to grasp a task. … She'd been focusing on this ewe—ignoring the others on the far side of the run—all night. … The ewe suddenly scrambled away, but Rose circled ahead of her. I got a crook around her neck and wrestled her onto her side, quietly asking her forgiveness for the rough treatment” (81). A picture of man and dog working together to save mother and lamb, this scene shows Rose as Katz characterizes her in the prologue: “heroic, determined, and her life is in service to me” (xvi).

But does this capture Rose’s subjectivity or, in Katz’s term, her soul? In Katz’s first chapter, entitled “Dogs and Souls,” he cursorily recapitulates the do-dogs-have-souls debate by sketching Aristotle’s and Aquinas’s contention that animals lack reason and hence souls, countering that liberal theologians and animal rights activists are currently promulgating different beliefs, and adding that studies by scientists and behaviorists are “oddly inclusive.” Finally, Katz asserts: “the question of dogs and souls can best be approached for my purposes not by scientists, pastors, or Ph.D.s, but through the animals themselves. … Researchers are amassing evidence … but so are the rest of us” (12). Not only does this assertion validate Katz’s series of books featuring tales of his companion animals at Bedlam Farm, but it also makes every member of his reading public an equally valid researcher to weigh in on the question of the human|non-human divide at the heart of posthumanism. By telling tales about the feats of our favorite pets, effectively anthropomorphizing them as heroes, and frequently elevating them as innocent beings representative of nature, we have used the genre of memoir, Katz alleges, to become effective researchers. Both Katz’s book and, as I examine later, Horowitz’s Inside of a Dog are using popular scientism as a rhetorical device to persuade readers of the authenticity of their narratives—a truth value that is not the “autobiographical pact” that Lejeune first averred, but the “authenticity effect” that Sidonie Smith identifies as integral to the imbricated autobiographies of Hillary Clinton.

However, claims about the scientific|empirical grounding of Soul of a Dog do not mean that such grounding really exists. Its lack of attributed sources and critical engagement makes me question the seriousness of Katz’s book, and disqualifies it as either new biography or critical posthumanism. Katz refers to the scholars and scientists invested in the posthumanist debate, but only to dismiss their expertise. He briefly mentions the history of pet-keeping to distinguish those much harsher times, marked by starvation, war, disease, suffering, and superstition, “from our presumably enlightened and progressive present” (7–8). He does not extensively lay out the histories and genealogies of companion species, specifically dogs, as Haraway does when she devotes chapters in When Species Meet to analyzing the rise of companion species as a recent concept, tracing the implications of that new nomenclature via the web of our everyday interactions with canines, and singling out the histories of specific breeds for extensive discussion. What I am asserting here is that, for animalographies to be taken as either worthy of a critical label (such as “new biography”) or as a serious contribution to the posthumanist debate, they need to be something more than a quick read that at best satisfies our ideological preconceptions. Furthermore, dramatic musings like Soul of a Dog fail to get at anything profound or enlightening about relationships between companion species and humans. Nor do they enact canine subjectivity, memory, or experience in any way that interrogates a human narrator speaking to a human audience via the human media of print or photography.

Katz’s book includes pictorial frames preceding each chapter about different companion species at Bedlam Farm. Most are black-line-bordered black-and-white head shots resembling a picture frame, presumably so that the viewer can see the soul of the respective animal through its eyes, which look straight ahead at the camera, level with the viewer, thus suggesting an equivalency between human and animal that effectively anthropomorphizes non-human animals. This technique suits the scopophilia of humans and does nothing to challenge the humanist rights doctrine of popular posthumanism, which advocates that animals need merely to possess the same rights to be on a par with humans. This technique also does nothing to represent the senses that are more important to non-human animals and their experience, such as smell and touch, thus effectively placing Soul of a Dog firmly in the category of popular posthumanism. It is interesting that the majority of the animal photographs within the covers of Soul of a Dog are of dogs, specifically of a Border collie, who is often presumed to be Rose, and that they are likely to have been taken by Katz, since the author’s profile lists him as a photographer among his other accomplishments. Of the seventeen black-and-white photographs in Soul of a Dog, including the one on the front cover, the one on the title page, and the one at the end of the book where Katz is pictured surrounded by dogs, ten images depict canines and eight feature a Border collie. It is telling that a Border collie—presumably Rose—is photographed in a field accompanying Katz and his tripod, that the black-and-white photograph is shot so that Katz and Rose appear in the foreground with the field and hills in the distance, and that this photograph is positioned before one of the book’s final chapters, entitled “Chasing Sunsets” (). It is equally revealing that on the paperback book’s color cover, half of a Border collie’s face, mouth slightly panting, stares straight at the reader, as if to invite the book’s purchaser to enter the soul of a dog by buying and reading Katz’s book.

FIGURE 1. Man and dog representing a “natural” scene S.Photographs from SOUL OF A DOG: REFLECTIONS ON THE SPIRITS OF THE ANIMALS OF BEDLAM FARM by Jon Katz, copyright © 2009 by Jon Katz, p. 138S. Used by permission of Villard Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

There is, of course, nothing innocent about the positioning of Border collie photographs between the book’s covers: it invokes a family album. From the small frontal-view head shot on the title page; to the half-body side shot of a Border collie lying down with an identification placard bearing the name Izzy Katz and the dog’s photograph resting on one of the Border collie’s legs; to the full body shot of Rose staring straight at the camera positioned to precede the chapter titled “The Soul of Rose;” to the head shot severely cropped to emphasize Rose’s face and eyes placed before “Rose and My Soul;” to an even more severely cropped partial head shot with the dog’s eyes (presumably Rose’s) occupying the foreground (), so as to force the viewer to penetrate their depths, positioned just before the epilogue entitled “The Mystery of Things”—the photographs in Soul of a Dog are meant to foster family resemblance and nurturing. Clearly, Katz thinks of the animals at Bedlam Farm as his family in the broadest sense of the term. Not only do the animals, particularly the dogs, cohabitate with him, but they likewise provide his major creature contacts and his livelihood, since writing about the animals at Bedlam Farm is how he supports them and himself. Katz’s endeavor is a cottage industry that the photographs in Soul of a Dog help to depict. The photographs also validate the naturalness of this idyllic life both because their subjects are animals and hence by definition natural, and because the setting is always rural. The photographs further function as speaking likenesses, as a tenacious communication between subject and viewer, for they seduce the viewer to follow Katz and leave the complicated life of the city for the lure of the innocent by entering the soul of a Border collie, if only for as long as it takes to read Soul of a Dog.

FIGURE 2. A Window on Rose's Soul. PhotographSS from SOUL OF A DOG: REFLECTIONS ON THE SPIRITS OF THE ANIMALS OF BEDLAM FARM by Jon Katz, copyright © 2009 by Jon Katz, p. 170. Used by permission of Villard Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Orlean’s critically acclaimed book Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend is a rich cultural exploration and carefully avoids the quasi-spiritual aura of Soul of a Dog. Like Katz’s book, however, Orlean’s work participates in the commodification of the canine-human narrative and uses visual as well as textual strategies to do so. Photographs frame the text of Rin Tin Tin—photographs of the mechanically reproduced plastic Rin Tin Tin; of the autographed photograph of the original Rin Tin Tin signed both by the dog and his master, Duncan; of Duncan with Rin Tin Tin as a puppy in France; of the heroic leap that catapulted the original Rin Tin Tin to movie fame; and of a later television celebrity Rin Tin Tin with his human pals, Rip and Rusty, encouraging the youth of the US to stay tuned in. All these photographs, and the written text that accompanies them, are part of answering the larger question of who and what is Rin Tin Tin, a dog, an experience, a performance—all that and more combined. Rin Tin Tin is a multimodal extravaganza not only because the book itself combines the visual and verbal, but also because both text and image point toward the multimodality that tells the complicated story of the life and legend. Like Soul of a Dog, Rin Tin Tin uses the medium of photography to accompany the written text, and both texts use photographs to produce an “authenticity effect.” Moreover, the grammar of photographs as indexical, as representational of an original—in this case, actual dogs—helps contribute to their functioning as pointing to the real and true. But unlike Soul of a Dog, the photographic effects in Rin Tin Tin are much more complex: in the schema of Charles Sanders Peirce, the Rin Tin Tin images are not only indexical, but iconic and nearly symbolic as well (239–40; Hill, “Psychology” 29). Ideology and cultural history have complicated both the images and the textual representation of Orlean’s German shepherd: the bios of Rin Tin Tin ranges more broadly than that of Katz’s featured canine, Rose. Not confined to a single location like Bedlam Farm, the original flesh-and-blood Rin Tin Tin leaves France to travel to California, and then journeys into the movies, fast achieving stardom and celebrity status. Hence, it makes sense to consider the photographs of the original Rin Tin Tin along with his descendants, both biological and virtual, within the context of the celebrity-photograph genre to track the process by which images become iconic as well as indexical, and verge on the symbolic.

In “Echoes of Camelot: How Images Construct Cultural Memory through Rhetorical Framing,” Janis L. Edwards discusses how iconographic images of the Kennedy family bios—such as the photograph of the salute that young John John made before his father John F. Kennedy’s coffin—achieved celebrity status and were circulated and recirculated to create a national community that in many ways transcended time and space. The “salute” photograph evoked a “pack” response, Edwards claims, by “invoking the mythic narrative of the Kennedy promise and the end of that promise” when John F. Kennedy, Jr. died in a plane crash (193). Although it may seem strange to put the dog Rin Tin Tin on a par with John F. Kennedy or his son even via the medium of a photograph, doing so helps elucidate the webbed relationship between humans and canines prefigured by the philosophical questioning of posthumanism, because thinking in these terms helps us understand how new biography might or might not translate visually.

The images in Orlean’s book, as Craig Stroupe writes about another multimodal text, “comprise an alternative, parallel text that doesn’t simply follow the verbal text, but rises and falls independently on … dialogical waves of discursive contention” (248). Between the covers of the hardback Rin Tin Tin there are seven black-and-white photographs. None of them sport the line framing device meant to recall a picture frame, they are all of a canine Rin Tin Tin, albeit sometimes accompanied by a human being, and they all frame the book’s major sections, except for the photograph placed before the title page. This photograph of the original Rin Tin Tin pictures him at a three-quarters-part upper-body angle with his muzzle pointing downward, his erect ears slightly flopping forward, and a pensive expression on his face. This is obviously a celebrity photograph. It is doubly signed in the photograph’s foreground directly below Rin Tin Tin’s muzzle, “Most faithfully Rin-Tin-Tin,” in large, bold, black script, with “Lee Duncan master and friend 1931” in smaller, bold, black script directly below Rin Tin Tin’s alleged signature. The effect of the photograph and its placement in Orlean’s text points to multiple complexities: the personal and professional relationship between Duncan and Rin Tin Tin; the dog’s celebrity status; and the evocation of a 1931 celebrity photograph to guide reader response to Orlean’s text. This photograph was clearly disseminated to the US public to foster Rin Tin Tin’s reputation, but what is interesting is that he is not pictured as a canine hero in action—as the embodiment of the qualities of courage and pluck that he exuded in his movies and that were encouraged to help lift Americans out of the Great Depression. Rather, he is thoughtful and, I would argue, this thinking pose puts him more on a par with human beings, as does the fiction that he can sign his name.

But if this gestures toward a pictorially conceived posthuman relationship between dog and man, it is simultaneously contradicted by the sign of Duncan’s signature, which verifies his correct, hierarchical relationship with Rin Tin Tin as master, even though Duncan is also inscribed as “friend.” In this celebrity photograph, Rin Tin Tin is presented to his public as a faithful, thinking dog, whose pensiveness contradicts the reputation, well established by 1931, of German shepherds as aggressive guard dogs; the cultural status and packaging of this photograph resonates with the “salute” photograph, where young John John observes the hierarchies of father and son as he respectfully says goodbye to John F. Kennedy. Both these celebrity photographs create icons which reinscribe proper relations—which tell viewers that, even when there is danger in the form of death or a dog bred to guard, all is right with the world (see Edwards). The placement of this celebrity photograph of Rin Tin Tin before the book’s title page with its subtitle, The Life and the Legend, communicates several things to the reader, most obviously that the text will deal with Rin Tin Tin’s bios as celebrity as much as with his life as a German shepherd; that Duncan is a major part of the Rin Tin Tin story; and that Rin Tin Tin functions as the quintessential faithful dog, who in his largeness and largess can succor his human friend, Duncan, as well as his fans.

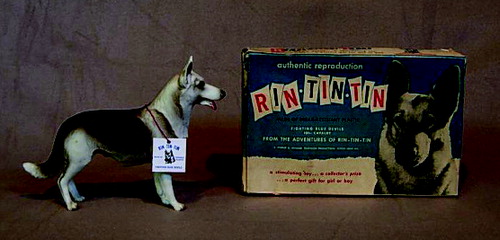

Perhaps the most disconcerting photograph in Rin Tin Tin is the one of a plastic Rin Tin Tin () that frames the short “Forever” section, which itself introduces the written text. Immediately, the viewer is jerked from seeing an indexical image to viewing a representation of a representation. The startling effect of seeing a plastic mold of a full-body representation of a German shepherd—tail down in the correct German shepherd pose; ears pricked and eyes staring straight ahead to show alertness; muzzle unnaturally elongated; mouth slightly open and panting, with tongue hanging out to convey excitement—arrests the viewer. Certainly, picturing a plastic representation of a German shepherd, and one whose coat markings indicate that this is not the flesh-and-blood Rin Tin Tin of the 1931 celebrity photograph, causes viewer dissonance; the only way we can begin to interpret its inclusion is to read Orlean’s autobiography, which extends the story of Rin Tin Tin autobiographically and biographically. This imbrication of image and writing, while bringing representationality front and center, plays with how the reader|viewer makes sense of multiple sign systems, while it also has the effect of posing questions for critics of life writing|narrative about new biography.

FIGURE 3. An original Rin Tin Tin plastic figure with box, made by Breyer Animal Creations from 1958 to 1966—the same model that Orlean’s grandfather kept out of the reach of his grandchildren. Photograph by Kirsten Wellman of White Horse Productions. Used by permission.

Certainly, Orlean’s biography is contextually, historically, and ideologically complex, and it intertwines Orlean’s life narrative with her excavation of the Rin Tin Tin legend. Orlean is a masterful writer and Rin Tin Tin is a wonderful read, especially for anyone even vaguely interested in dogs, for it celebrates the fervent belief in and love that orphan Duncan felt for the German shepherd puppy he found abandoned with his dam and littermates in a bombed-out World War I German compound in Fluiry, France—a village that has changed hands so many times it scarcely now exists. Faith and determination, a boy’s love for his dog, the boom-and-bust cycle of US success, and its apotheosis in the glitter and glamor of Hollywood—in short, diverse components of the American Dream—relentlessly frame the pages of the book Rin Tin Tin. Interspersed with this is Orlean’s counterpoint story of longing, loss, and secrets; of her desire to hold the plastic Rin Tin Tin figure her austere grandfather denied his grandchildren; of the shards of information left her to learn about her Polish relatives who died in the Holocaust; and of the family’s secrecy about what happened to aunts and uncles. Rin Tin Tin is a tour-de-force of life in the twentieth-century US and of the frames we use to package the US experience. At its center is a dog, but its raison d'être is to painstakingly trace US urbanization, the impact of World War I on those who fought and those who stayed at home, the growth of the movies and the advent of television, and the bourgeoning of a youth consumer culture after World War II. Orlean is a fine researcher who lets her readers know that she visited Rin Tin Tin’s birthplace; spent years sifting through the Rin Tin Tin archives housed in Riverside, California; watched the Rin Tin Tin silent and talkie movies that remain; and tracked down anybody and everybody living who was associated with the first Rin Tin Tin, his descendants, or his reincarnations. Unlike Katz’s Soul of a Dog, Rin Tin Tin includes notes on sources, though not the scholarly apparatus of citations, and suggests epic proportions, which are carefully documented.

But does it tell the story of the original canine Rin Tin Tin—his subjectivity, memory, and experience? The answer is no. The original Rin Tin Tin, the German shepherd whom Duncan helped make into a Hollywood phenomenon, is only the coaxer of the story, the center point that focuses the many biographies of all the people in some way associated with the original canine phenomenon or his legacy, whether biological, cinematic, or commercial. Orlean distinguishes Duncan, who cared deeply about the flesh-and-blood original Rin Tin Tin, from Bert Leonard, who was emotionally invested in Rin Tin Tin as an image, and from Daphne Hereford, who claims to have “the living legacy of Rin Tin Tin dogs in Texas” (258). Telling biographies of the central actors in the Rin Tin Tin story might seem to place the text in the category of new biography and gesture toward the genealogical methodology Haraway uses in When Species Meet. But it does neither. New biography interrogates narrative frames, leading us to revisit and revise how we tell stories, how we think about how they are told, and how they circumscribe our lives. One of the recurring tropes, as well as a fascinating phenomenon in Rin Tin Tin, is the Memory Room, which was first an archive maintained by Lee Duncan to celebrate and keep alive the dog he never wanted to die. But as any good author and|or critic knows, memory as concept and articulation is tricky, and very human. Orlean effectively exploits this when she writes about Rin Tin Tin and Me, the movie script depicting the intense relationship between Rin Tin Tin and Duncan that Leonard had been working on for almost fifty years: “The outline of the story followed the outline of Lee’s life, but the character was not quite Lee. … It was as if Bert was grafting some of his personality onto the cinematic version of the Lee Duncan he was creating. … It was his version of a Memory Room, in the form of a movie, where he had always felt most at home” (305).

If, as I have suggested, Rin Tin Tin is not new biography, what then would we call the effect of this multimodal text? Put simply, I would argue that the complex interplay of written text and visual image, of life story set against life story, creates an imagined community where text and image perform important cultural work by exploiting and reinforcing common values (Hill, “Reading” 116), not least because Orlean’s text is itself a study of the effects of media on lives and consciousness. Although it is common practice to use photographic images to frame sections to a written text, the use of these in Rin Tin Tin seems more than simple mimesis, as my earlier comments about the image of the plastic German shepherd—meant to represent the flesh-and-blood canine movie star, yet suggestive of any German shepherd dog—show. What disconcerts the viewer and helps create the effect of an imagined community of Rin Tin Tin fans and of virtual and actual German shepherd dogs that represent the Rin Tin Tin icon is the inclusion of images that can be read as straightforwardly indexical, as well as those that obviously promote iconic celebrity status. The out-of-focus black-and-white straight-on photograph of Rin Tin Tin and his litter-sister foregrounded and lying in the laps of two smiling soldiers, who are themselves positioned in front of two lines of sitting, smiling soldiers, who in turn have behind them standing soldiers whose heads are cut off by the photograph’s frame, is placed before the section entitled “Foundlings.” This photograph is meant to help tell the origin story of the first Rin Tin Tin, his orphan status, and the beginning of his rise as a self-made canine, but it also shows that, once he was found, the future dog celebrity became the focus of caring humans, specifically Duncan. The bond of the man-dog relationship is apparent here; the message conveyed is that a dog is a man’s best friend. The only other photograph between the covers of Rin Tin Tin that conveys the message of the bond between man and dog is the one of a silver-haired Duncan, arms and legs crossed and staring straight ahead, lying on the grass with the original Rin Tin Tin, ears alertly pricked, staring straight ahead, with his head at a three-quarters angle and one leg tucked under his body. The photograph is shot from above and obliquely, and is staged to show the casual, bonded relationship between master|promoter and dog star, which is also conveyed by Rin Tin Tin wearing a studded V-shaped harness and Duncan being dressed in a striped turtle-neck sweater. The obviously staged quality of this photograph, placed before the section titled “Heroes,” indicates that the once-straightforward relationship between Duncan and Rin Tin Tin has become more complicated, more imagined, even if it is depicted as casual.

If these photographs of the original Rin Tin Tin with soldiers and with Lee Duncan seem “natural,” in that they represent the essentialized man-dog relationship, the other photographs contained within the covers of Rin Tin Tin more obviously show Rin Tin Tin as a canine icon—as the metonymic representation of an imagined community. One is of the original Rin Tin Tin, with pricked ears and head titled slightly downward, shot full-frontal sitting behind a typewriter with a sheet of paper in its carriage and the background faded out (). Here, Rin Tin Tin is anthropomorphized into the quintessential representation of the creative, writing canine, a dog allegedly so talented that he can tell his own story or perhaps write the scripts for the movies in which he stars. His increasingly human and even godlike status shows that he is literally larger than life, a canine creative force able to will his image into being. Not surprisingly, this photograph precedes “The Silver Screen” section of the book.

Rin Tin Tin as a super athlete, as a canine hero who could perhaps leap tall buildings, would seem to be the ideological message of the photograph picturing the original Rin Tin Tin pulling himself over an almost twelve-foot-high jump bearing a crest with the message “Rin Tin Tin Imported” and also featuring a US flag waving behind him and a man at the left-hand side of the jump witnessing the feat of this marvelous canine athlete. If the flag clearly indicates that Rin Tin Tin is an American hero, despite his German origins, the man, his hands on hips and standing on the ground, by being positioned lower and to the side of Rin Tin Tin shows that the dog and his extraordinary feat dwarf the man’s capabilities. Rin Tin Tin’s jumping prowess helped catapult him to stardom, according to Orlean, but this iconic photograph of Rin Tin Tin is placed before the section entitled “The Leap,” in this case symbolically connecting the original physical act with Orlean’s discussion of how the imagined community occurred, which extends from the first Rin Tin Tin, to his biological and cinematic descendants, to the Hollywood creators who fostered that image, and finally to the admirers whose adoration has kept it alive. Bringing to life and sustaining any imagined community is a complicated endeavor that occupies, provides a living for, and sustains a reason to believe for any involved group of people, and the one that bears the brand of Rin Tin Tin is no exception. This is why the brand of Rin Tin Tin literally could not die, even if, as was inevitable, the flesh-and-blood puppy found by Duncan in France did. Rin Tin Tin has lived on in his descendants, but, more importantly for sustaining an imagined community, he has lived on in photographs that recall the original dog.

Two photographs connected with Rin Tin Tin remain in Orlean’s book, the dog in neither of which looks anything like the original Rin Tin Tin. The photograph placed before the section entitled The Phenomenon, we surmise from Orlean’s written text, is of Rin Tin Tin IV, who carried on the Rin Tin Tin legacy by being transposed from film to the relatively new and increasingly popular medium of television, whose capacity to reach viewers in their own homes adds yet another twist to the concept of an imagined community. In his promotional shot, the lightly colored Rin Tin Tin IV, in contrast to his darkly marked progenitor, is pictured as a “family” dog, a canine companion who promises wholesome male bonding in the great outdoors, for he is depicted sitting on a rocky ledge between a boy and a man, both of whom are white and clean-cut, and dressed in cavalry uniforms reminiscent of the Boy Scouts and Western adventure (). Yet Rin Tin Tin IV is also literate, since he can sign, if only with a paw print, the brief letter to young viewers thanking them for writing, promising “lots of action and adventure” in the television series, and urging them to stay tuned. Rin Tin Tin IV continues an iconic brand but, in so doing, his representationality creates a seemingly endless stream of signifiers that appear to extend to all German shepherd dogs.

FIGURE 5. Rin Tin Tin and family posing as calvary troopers. Reproduced by permission of Getty Images.

The final example of paratextuality—the dust jacket of Rin Tin Tin—foregrounds the head of a German shepherd photographed in color from behind, with his iconic ears pricked, slightly panting and looking into the black-and-white background at a man and dog walking and melting into a cloud-covered, brooding Western setting. Here, the German shepherd dog dominates because he is the viewer of the scene, his image is foregrounded, and he is pictured in color. The message that the viewer|reader receives even before opening the text of Rin Tin Tin is the power of the dog’s vision, the scope of his reach, and his ability to command and create an imagined community, as suggested by the subtitle, The Life and the Legend, placed in the cloud cover of the image and just to the right of the dog’s ears. It does not matter that this is not the original Rin Tin Tin; even on the dust jacket he has become representative of all German shepherd dogs—in fact of all dogs who project iconic power and symbolize the community’s ideological values.

If the images in Rin Tin Tin fall within the realm of indexical photographic depiction, the black line drawings interspersed throughout Inside of a Dog seem abstract, yet denotative and in keeping with the fine line between scientific observation and public education that Horowitz treads. Diagrams are used by scientists to represent typology, while photographs are considered too individual and thus not reliable for conveying scientific knowledge. However, if the audience of a scientific text is younger or less inducted into the visual rhetoric of science, the diagrams are more naturally conceived, as is the case with the line drawings in Inside of a Dog. The diagrams included in Horowitz’s book exhibit the circular and curved form associated with the natural order, even evoking the whimsicality of children’s drawings, and seem to be randomly placed in the written text, in contrast to the photographs framing sections in both Soul of a Dog and Rin Tin Tin. Given Horowitz’s delicately negotiated stance as a scientific writer whose mission it is to educate the general public about canine behavior, using line drawings and placing them randomly makes sense, for both tactics create the effect of initiating the uninformed into newly conceived relations—specifically, new and improved canine-human interaction. In fact, the line drawings function as ideographs. Through their representation of the sign “dog,” they convey a sign system of canine behavior. Of the twenty-five line drawings, or grouping of drawings, between the covers of Inside of a Dog, the vast majority represent doggy activities that many humans obviously do not adequately understand: dogs' acute sense of smell, and dog communication via tail-wagging, ear placement, and urine-marking, for example.

But if these ideographs help humans learn to read dogs’ body language, others show dogs’ ability to problem-solve. Introducing the section entitled “Dogs' Psychic Powers Deconstructed,” as part of the chapter “Canine Anthropologists,” is a drawing of a sitting dog in profile, with his tail laid out behind him and eyes, nose, and ears sketched in, staring straight ahead (). Read in conjunction with Horowitz’s written text, the message is that dogs spend most of their time reading humans by staring at them, which any human companion who is at all observant knows, and which is one of the reasons why dogs have been lauded as a man’s best friend.

But dogs’ ability to problem-solve does not always involve adoring interaction with humans and can, in fact, show that dogs are canny enough to use humans in the support role of tool. The ideograph picturing a canine with half his body inside a box, tail held high and one leg raised, depicts the kind of intelligence test that scientists have used to assess canine behavior. But this does not tell the whole story, or tell it accurately, since “dogs are terrific at using humans to solve problems, but not as good at solving problems when we’re not around” (Horowitz 181). This is one of two ideographs in the chapter entitled “Noble Mind,” where Horowitz explores memory as a quality that may or may not separate humans from non-human animals.

Unlike in Rin Tin Tin where memory is a distinctly human quality, memory, subjectivity, and especially experience are all central issues that are troubled in the canine experience allegedly captured in Inside of a Dog; likewise, they are essential questions in posthumanism, as well as in life-writing studies. The bulk of the book tries to capture the canine Umwelt, or experience, as the key to communicating how dogs’ subjectivity differs from humans—namely, that dogs experience the world closer to the ground and via the senses of smell and touch more than the human sense of sight. In order to achieve this, Horowitz takes pains to educate average dog owners, particularly urban ones who routinely dress their dogs, by placing humans in the position of “an anthropologist in a foreign land—one peopled entirely by dogs” (31), and considering two dimensions that make up dogs’ Umwelt: history and anatomy. The first dimension gets short shrift, both because Horowitz is clearly biased against purebred dogs and because she is a cognitive scientist specializing in dog research. The perspective of science, then, frames Inside of a Dog, a perspective that “considers animals as representative of their species first, and as individuals second,” so that “when I talk about the dog, I am talking implicitly about those dogs studied to date” (8, 9). Given this approach and Horowitz’s statement that “[p]rofessionally, I am wary of anthropomorphizing animals” (3), it is curious that Inside of a Dog also features Horowitz’s fond memories of her dog, Pumpernickel, affectionately referred to as Pump.

Is Inside of a Dog, then, new biography, a means to link animal studies with life-writing studies via the shared concerns of subjectivity, memory, and experience? Does Horowitz’s inclusion of her memories of Pump alongside behaviorist explanations of a smell walk, play signals, and social panting, among other canine behaviors, make this text representative of critical posthumanism? Inside of a Dog is interesting and especially useful for people whose lack of canine knowledge extends to not knowing that a tick is a parasite, which Horowitz explains when discussing Jacob von Uexküll’s concept of Umwelt. Even though she evokes Umwelt—a concept essential to posthumanist thought—Horowitz’s failure to interweave her memories of Pump with her explanations of canine experience so that the two mutually illuminate each other to challenge received narrative frames disqualifies her book as posthumanist or as new biography. So, too, does her truncated explanation of canine history, which fails to show how genealogical knowledge prompts revisioning of our idea of the dog in Haraway's dense and interlinking methodology. Interestingly, Horowitz specifically addresses dogs' autobiographical memory, saying that “[n]o experimental study has specifically tested the dog’s considerations of his own past or future” (226), and asserts that “they are writing [autobiography] right now in front of you” (228), an assertion that supports her contention that “No animal can be asked to relate its experience in voice or paper, so behavior must be our guide” (145). This traditional anthropological stance, critiqued by feminists and post-colonial critics, among others, for the past several decades, purports that because we cannot know the Other, we rely on our observed experience of their behavior. Of the three animalographies I have discussed, Inside of a Dog most clearly and completely attempts to represent dog experience. However, by doing this so exclusively from a behaviorist framework and leaving out much discussion of the ideological contexts, historical relationship, and personal relating of canines and humans as companion species, Horowitz undermines crossing the species divide.

Horowitz’s view into the inside of a dog remains extremely popular, topping the New York Times best-seller list for paperback nonfiction in 2011. Horowitz’s and Orlean’s books held pride of place in the pile of animalographies that confronted me in Barnes and Noble on that muggy summer day. While such works purport to narrate a dog’s experience, or human experience enfolded with dogs, they narrate instead the ideologies from which they spring: commodification, scientism and empiricism, spiritualism, and celebrity culture. In order to pose as biographical and to convince us of the authenticity of their accounts, Soul of a Dog, Rin Tin Tin, and Inside of a Dog use the textual genres of autobiography with spiritual reflection, cultural history, and empirical treatise, as well as the visual rhetorics we know well, to persuade us that we have learned something startlingly new about ourselves and our relationships with dogs. Not new biography, not a critical posthumanist representation of the canine-human relationship, these texts add to our knowledge, but do not complicate and extend our performance of subjectivities or our exploration of the breadth and nexus of life writing.

Notes

1. Roland Barthes identified three messages in any image: its linguistic message (how it is tied to text), its denotative message, and its connotative message (or the way it conveys cultural ideologies). Most importantly, these are all discontinuous, so that images both generate meaning we expect from a verbal text and disrupt it by importing uncoded cultural meanings.

2. The term “new biography” stems from a review by Virginia Woolf and was most explicitly defined and practiced in the 1920s and 1930s. As Smith and Watson note, in the early years of the twenty-first century, US biographers were redeploying the term to describe their work and to denote as well the autobiographical impulse inherent in much modern scholarly writing (297–98). In defining this “innovative” genre, Smith and Watson cite Carolyn Steedman’s Landscape for a Good Woman because Steedman uses a case-study approach, telling the stories of her parents alongside her own and interspersing each family member’s story with critical, scholarly commentary that interrogates received working-class narratives (8). See also Hoberman.

Works Cited

- Adams, Timothy Dow. Light Writing and Life Writing: Photography in Autobiography. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2000. Print.

- Barthes, Roland. “Rhetoric of the Image.” Handa 152–63. Print.

- Chute, Hillary L. Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. New York: Columbia UP, 2010. Print.

- Couser, G. Thomas. “A Personal Post(Human) Script.” Whitlock and Couser 190–97. Print.

- Edwards, Janis L. “Echoes of Camelot: How Images Construct Cultural Memory through Rhetorical Framing.” Hill and Helmers 179–94. Print.

- Handa, Carolyn, ed. Visual Rhetoric in a Digital World. Boston: Bedford|St. Martin’s, 2004. Print.

- Haraway, Donna J. When Species Meet. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008. Print.

- Hill, Charles A. “The Psychology of Rhetorical Images.” Hill and Helmers 25–40. Print.

- —. “Reading the Visual in College Writing Classes.” Handa 107–30. Print.

- Hill, Charles A., and Marguerite Helmers, eds. Defining Visual Rhetorics. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2004. Print.

- Hirsch, Marianne. Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1997. Print.

- Hoberman, Ruth. “New Biography.” Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Ed. Margaretta Jolly. London: Dearborn, 2001. 650–51. Print.

- Hocks, Mary E. “Understanding Visual Rhetoric in Digital Writing Environments.” CCC 54.4 (2003): 629–56. Print.

- Horowitz, Alexandra. Inside of a Dog: What Dogs See, Smell, and Know. New York: Scribner’s, 2009. Print.

- Huff, Cynthia, and Joel Haefner. “His Master’s Voice: Animalographies, Life Writing, and the Posthuman.” Whitlock and Couser 153–69. Print.

- Katz, Jon. Soul of a Dog: Reflections on the Spirits of the Animals of Bedlam Farm. New York: Random, 2009. Print.

- Lejeune, Philippe. On Autobiography. Trans. Katherine Leary. Ed. John Paul Eakin. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1989. Print.

- Miller, Nancy K. “The Entangled Self: Genre Bondage in the Age of the Memoir.” PMLA 122.2 (2007): 537–48. Print.

- Orlean, Susan. Rin Tin Tin: The Life and the Legend. New York: Simon, 2011. Print.

- Peirce, Charles Sanders. Peirce on Signs: Writings on Semiotic by Charles Sanders Peirce. Ed. James Hoopes. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1991. Print.

- Rogoff, Irit. “Studying Visual Culture.” Handa 381–94. Print.

- Simon, Bart. “Introduction: Toward a Critique of Posthuman Futures.” Cultural Critique 53 (2003): 1–9. Print.

- Smith, Sidonie. “‘America’s Exhibit A’: Hillary Clinton’s Living History and the Genres of Authenticity.” International Autobiography Assn. Conference. U of Sussex, Brighton. 29 July 2010. Address.

- Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. 2nd ed. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2010. Print.

- Steedman, Carolyn. Landscape for a Good Woman. New Brunswick Rutgers UP, 1986. Print.

- Stroupe, Craig. “The Rhetoric of Irritation: Inappropriateness as Visual|Literate Practice.” Hill and Helmers 243–58. Print.

- Whitlock, Gillian, and G. Thomas Couser, eds. (Post)Human Lives. Spec. issue of Biography 35.1 (2012): 153–169. Print.

- Wolfe, Cary. What is Posthumanism? Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2010. Print.