Two images locate this special issue. The first is the portrait on the cover of “Life Writing in the Anthropocene,” from Anna Laurent’s immersive installation Flora: Exploration to Extinction. This site-specific installation was commissioned for the corridors of the Exhibitionist Hotel in South Kensington, London, in 2018. Arranged on the saturated color of the emerald walls, the gilt frames emphasize the portrait presentation of black silhouettes of species of extinct or endangered flora, each accompanied by an information panel including the plant name, native ecology, and ecological pressures. Laurent chose black silhouettes to signify the absence of these plants in the landscape, as well as a historical reference to conventions of Victorian portraiture and nineteenth-century plant exploration, a period during which “species traveled the globe and luxurious images of flora were fetishized,” particularly in an era of perceived ecological abundance.1 Here, the gilt frames are surrounded by dried seed heads and leaves, preserved relics of plant life that are spray-painted gold. The specific silhouette we have selected for the cover is the miniature cactus Biznaguita (Mammillaria sanchez-mejoradae), which is endemic to one location in Neuvo León, Mexico. Its population has reduced by seventy-five percent in fifteen years and it is at risk of extinction due to illegal collection and climate change.2

Laurent’s immersive installation signals the turn to plant life (and extinction), which is a theme of this issue on the Anthropocene. The juxtaposition of portraiture—traditionally a depiction of an individual person of significance in humanist life narrative—and endangered flora in Laurent’s artwork introduces the immersion in “phytographia”—”human writings about plant lives as well as plant writings about their own lives”3—which is a feature of this special issue. Laurent’s turn to portraiture and extinction also captures a key feature of the Anthropocene: it is, “first and foremost, about death on an unimaginable scale”.4

This special issue is a companion to the preceding issue of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies on “Engaging Donna Haraway: Lives in the Natureculture Web.” We sustain its questioning of what constitutes a life, how that life is narrated, and what lives matter in autobiography studies now, and the turn to “phytographia” in this issue complements the focus on animal lives there. As Cynthia Huff argues in her essay on the autobiographical pact in this preceding issue, the environment of our research field has changed significantly, with a posthuman turn that eschews the human as a principal actant in favor of the distributive agency of the animal, the machine, inanimate matter, and the human.5 For almost a decade now, special issues of journals, such as these companion issues, have led this turn from the human signature to “posthuman lives.”6 The distinctive contribution of this specific issue to this tradition of innovative scholarship is an emerging recognition of plant life, which thrives here in “ecobiography” (White), “ethological poetics” (Cooke), “phytography” (Ryan), “the witness tree” (Connor), “ethnomycology” (Harley), the commodification of plant life in the “Plantationocene” (Krieg), and “wheaten childhoods” of settler colonialism (Hughes-d’Aeth). Laurent’s installation and its turn to portraiture and the silhouette to represent plant life (and extinction) captures this botanical turn, as well as the definitive force of thinking in terms of the age of the Anthropocene—the “extravagant wastage of lives and of earth.”7

That autobiography studies as a field of research should engage with debates in environmental humanities on the issue of the Anthropocene in this way is not surprising. Kate Douglas and Ashley Barnwell argue in their recent reflections on Research Methodologies for Auto/biography Studies that this has been one of the most vibrant interdisciplines to emerge in the humanities and the social sciences in the past decade, moving across literary and creative writing, history, gender studies, education, sociology, and anthropology.8 As Huff asserts, this transforms the autobiographical pact into the zoetrophic pact, encompassing “not just ‘bio’ but zoe—that is, life that has generally been considered so insignificant as to be killable.”9 These companion issues of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies, addressing the politics and poetics of the environment in this interdiscipline, capture the dynamism and agency of this field and its imbrication in issues of social justice, which transform the discourse of human rights and narrated lives by extending the ethics of recognition to the material presence of other-than-human life.

As a concept, the Anthropocene is distinguished by its grasp of humans as a geophysical force, shaping the planet’s biophysical systems through the combustion of fossil fuels and production of carbon, unprecedented population growth, transformation of the earth’s land surface and water flows, and mass extinction. While scholarship on these man-made changes to the earth has circulated since the nineteenth century,10 atmospheric chemist and Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen and biologist Eugene Stoermer formalized the term “Anthropocene” in 2000 to “emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology.”11 The term has pervaded the sciences and humanities, and is now under formal consideration as a possible addition to the Geological Time Scale by an Anthropocene Working Group of the Internal Commission on Stratigraphy, thereby joining other ages such as the Jurassic and Pleistocene.12 The term is not without its critics. Australian novelist James Bradley resists “the way its assertion of human primacy reiterates the blindness that got us here.”13 He prefers biologist and conservationist Edward O. Wilson’s term “Eremocene,” the Age of Loneliness.14 Other concepts that stake a claim here include the Capitalocene, reflecting the role of capitalism in creating the carbon bomb, as well as discussions regarding the start date for the Anthropocene, with Crutzen and Stoemer arguing for the late 1700s, a time when the effects of human activity became noticeable (ice cores, for example, record an increase of carbon dioxide), which also coincided with James Watt’s invention of the steam engine, an agent of the Industrial Revolution.15 The Necrocene points to deaths of the sixth mass extinction that surround us; the Plantationocene refers to the transformation of farms and estates into plantations that extract, via exploitation, human labor; and Donna Haraway’s Chthulucene identifies an era defined by its focus on a web of relationships, “a timeplace for learning to stay with the trouble of living and dying in response-ability to a damaged earth.”16

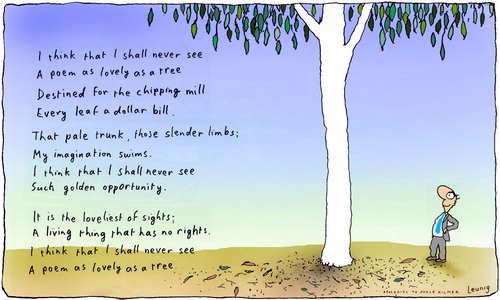

The second image we have chosen to introduce this special issue on life writing in the Anthropocene is a cartoon by Michael Leunig (), which takes its inspiration from Joyce Kilmer’s poem “Trees.” Leunig’s poem is, we recognize, whimsical, although it belies a serious message. By placing trees and arboreal discourse at the center of our life-writing narratives, we question our awareness of and interaction with other-than-humans. This issue is an attempt to imagine and interrogate how to write about those “living things that have no rights,” that are of value only in terms of commodification.17 The question of human rights and narrated lives has been germane to the energy of life narrative as an interdisciplinary field. However, at any historical moment, only certain stories are tellable and intelligible to a broader audience in terms of rights discourse.18 Questioning “the human” and, with it, some of the key tenets of the “bio” of auto|biography, such as the status of the human and the rights of other-than-human things, calls into question the ethics of recognition of rights-based discourse and its modernist language of rights and social justice for embodied individuals. This issue, like “Engaging Donna Haraway: Lives in the Natureculture Web,” suggests that the posthuman turn in life-writing theory and practice now engages critically and creatively with Anthropocene landscapes of death and extinction, and “emergent and unexpected constellations of life, nonlife, and afterlife”.19

The force of both Laurent’s portraits and Leunig’s cartoon suggests the importance of artistic practice as well as scholarly theory in expanding thinking on life matters and life writing. This issue of a/b is, as always, practice-led, beginning with a section that presents insights into the craft and construction of Anthropocene life writing. As coeditor, Jessica White’s critical and creative writing has been germane to the botanical focus of this issue, and her essay on writing an ecobiography of the settler-botanist Georgiana Molloy returns to nineteenth-century botanizing, a discourse Laurent evokes in the Flora: Exploration to Extinction installation. Molloy has been the subject of several significant biographies to date. However, it is only in ecobiography that the specimens she collects feature as significant life forms. The Southwest Australian Floristic Region is the focus of this decolonizing ecobiography, and Molloy’s numerous letters suggest how the unique and exquisite flora of this ecosystem are instrumental (rather than incidental) to her sense of self as a settler woman. Decolonizing ecobiography expands chronology to incorporate the deep time of both biological systems and Indigenous lifeways, and here, as throughout this issue, anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose’s concepts of “nourishing terrains” and “country,” drawing on Indigenous knowledges, are critical. Given the scale of ecological devastation and collapse, new modes of storytelling are required to convey our interconnection with, and responsibility to, things other than humans.

Rose’s work on “writing into the Anthropocene” inspires two other essays on the writing process.20 Thomas Bristow’s experimental “Sebaldian stereometry,” composed in a series of embodied “Anthropocene field notes” and “countersignatures,” is crafted precisely in place and time: Townsville, North Queensland, Australia, on the eve of a federal election where climate change, the proposed Adani coal mine, and the conservation of the Great Barrier Reef become critically important in the national conversation on the environment.21 In an echo of other pieces in this special issue, Bristow’s incorporation of diary, image, and descriptions of walks with his companion animal engenders a porousness in his writing, an openness and dialogue with spaces and their other-than-human inhabitants. Stereometry, Bristow argues, may be a way in which we can “delete the privatized human ‘I’” by pointing to “a world where nothing is final or absolute”.22

Stuart Cooke’s essay on ethological poetics and other-than-human lives also turns to Rose’s concept of “mutualism” to explore ways of articulating other-than-human language and expression, crafting forms of poetry open to the “vastly different Umwelten of their subjects”.23 Questioning how we might broaden our understanding of the interpellation of the other-than-human into human lives, Cooke draws on the concept of “ethological poetics,” or “the study of nonhuman poetic forms”,24 to encourage the understanding that there is a myriad of signals in the other-than-human world. This unsettles, as mycorrhizal fungi do, assumptions accompanying the classification of plants and animals (using Western taxonomic systems) that stymie understandings of interactions between humans and other-than-humans. This creative practice sets out to “translate the expression of a particular Australasian species or landform (such as a house fly, a tea tree, or an estuary) into human language”.25

Indeed, the presence of Rose, who died late last year, beats in this issue like a pulse, particularly her acknowledgment of Australian Aboriginal peoples’ deep and abiding relationship to country. In Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness, Rose explains that country is “a living entity with a yesterday, today and tomorrow, with a consciousness and a will towards life.”26 Those who do not care for or respect their ecosystem will find that it is unable to support them: “The interdependence of all life within country constitutes a hard but essential lesson—those who destroy their country ultimately destroy themselves.”27 Given that the Anthropocene is marked by mass extinction, it was perhaps inevitable that this issue on the Anthropocene might trigger extraordinary and experimental creative essays on death, on the powers of grief and mourning, or on “memoir and the end of the natural world” (Hughes-d’Aeth; this issue).

How does the obituary function present itself in Anthropocene life writing, asks Bristow, and how will it transform existing rhetorical categories and genres, such as the elegy? This question of how the Anthropocene shapes genres and conventions recurs in Astrid Joutseno’s haunting thanatography on “[b]ecoming ill with what will be the cause of my time’s end”.28 This feminist intersectional analysis draws on Haraway’s “tentacular thinking” and Rosi Braidotti’s affirmative ethics—“choosing to look for hope while acknowledging the sadness around losses in the Anthropocene”29—and engages with the archive of the other-than-human self to “consciously exit life”.30 Here, once again, we return to Laurent’s immersive installation, which transforms the conventions of portraiture and the silhouette to narrate the extinction of plant life.

This special issue, like its companion issue “Engaging Donna Haraway: Lives in the Natureculture Web,” commemorates a scholar who transforms how we understand life matters.31 Stephen Muecke’s essay, “Her Biography: Deborah Bird Rose,” is a further example of creative practice in the Anthropocene, transforming the conventions of the obituary to do justice to the “plural and complicated”32 connections of humans and other-than-humans that are alive in Bird’s research. “I have to talk a little about totemism,” he explains, “because she revived the concept of totemism as a shared-life concept that distributed rights and responsibilities for ecological management”.33 The interdependence of all life in country returns here. “Deborah Bird Rose became a flying-fox woman after she went to Yarralin … The flying fox thus shared her life and extended her life into the environment in a logical way—a logic of care, rights, and responsibilities”.34

No clear, bright line establishes a boundary between The Process and Essays, critical and creative writing, in this issue. We see, for example, bibliographies of both critical and creative writing, suggesting a body of scholarship that now inspires interdisciplinary writing on the Anthropocene: Karen Barad, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, Jane Bennett, Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Deborah Bird Rose, Timothy Morton, Amitav Ghosh, Cynthia Huff, and Stephen Muecke—among others—are all participants in this critical conversation. A distinctive contribution of this special issue on “Life Writing in the Anthropocene” to current scholarship on posthuman lives is the turn to writing the lives of plants. John Charles Ryan proposes that this is a new form of life writing: “phytographia.” His essay, “Writing the Lives of Plants: Phytography and the Botanical Imagination,” encourages an attentiveness that seeks and recognizes, in botanical prose and poetry (and, by extension, in the real world), the individual plant amidst a mass of foliage. Engineering the form of phytography, or, as he explains, “critical posthumanist life writing about more-than-humans,” “pivots on the potential of collaborating and coauthoring narratives with plants”.35 Ryan addresses an as yet largely unexamined area in the field of life writing, which has tended to dwell on the lives of humans and other-than-human animals.

Phytography entails careful attention to individual plants and their habitus, their unique forms and voices. This attentiveness features in Eamonn Connor’s essay “‘If a Tree Falls …’: Posthuman Testimony in C. D. Wright’s Casting Deep Shade,” which contemplates a book that is both formed and informed by trees. A three-paneled object, this “bok” is made of paper from trees and its spine is like a trunk. It materializes Wright’s acts of witnessing and, as Connor writes, “a subject position that exceeds her-self”.36 These acts create a “beech-consciousness,” which draws Wright into the assemblage of things that disrupt the singular notion of a “life.” Connor’s essay draws on testimony and witness as a mediating discourse between the human and the other-than-human, as Wright summons a reader who is capable of bearing witness to testimony that emerges from beyond a bounded human subject and returns to the theme of extending life into the environment with a logic of care, rights, and responsibilities.

The contingencies of living things are also laid bare in Alexis Harley’s essay, “Writing the Lives of Fungi at the End of the World,” an examination of three life narratives of mycorrhizal fungi and their symbionts. Tracing the ascendancy of humanism in the Enlightenment, and its subsequent unraveling with the Anthropocene, Harley illuminates how the indeterminacy of fungi (they are, for example, difficult to classify with traditional taxonomy) might prompt us to consider how we are never merely human but are constituted by our relations with other-than-human selves. Fungal agency problematizes “a common implication of the term ‘Anthropocene’—namely, that the relationship between humans and the rest of the world operates in one direction only, the agential human acting upon inert nature”,37 rather than being a co-constitutive relation that generates unexpected relationships. Turning to Bruno Latour’s writing on living in the epoch of the Anthropocene, Harley focuses on changing notions of the subject and subjection in response to the agency of earth, matter, and nature.

Two essays on memoir in this issue turn to colonization and race and the settler-colonial foundations of Anthropocene histories in the agricultural commodification of plant life: cotton and wheat. In “Planetary Delta: Anthropocene Lives in the Blues Memoir,” Parker Krieg challenges periodization of the Anthropocene that excludes colonial and plantation geographies by situating blues memoirs in an alternative framing—the Plantationocene, which foregrounds attention to “[t]he colonial combination of field and factory, and its various returns in contemporary global capitalism”.38 Here, blues memoirs of artists from the Mississippi Delta are read as a record of life writing in the Anthropocene which speaks to contemporary environmental culture and the economic and racial history of Anthropogenic environmental change. These memoirs mirror this situatedness, Krieg writes, wherein “authors’ encounters with the blues connect them to a tradition that links their life narratives to broader material memories of planetary production and exchange”.39 In a different yet related context, Tony Hughes-d’Aeth’s essay on the commodification of wheat and reflections on the “wheaten childhoods” of Wallace Stegner, Dorothy Hewett, and Barbara York Main question the capacity of memoir to bear witness to the event of the Anthropocene in the Americas and Australia. Drawing on Dipesh Chakrabarty’s influential essay on the impact of climate change for history, and the crisis of the historical subject that falls from this, this essay features the agency of wheat as a commodity that “works its logic into the landscape relentlessly, drawing human actors (settlers) into its incessant production while dispelling other human actors (Indigenous peoples) from the lives they have lived for millennia”.40 As global agricultural commodities, both cotton and wheat are critical agents of settler-colonial histories, and decolonizing scholarship questions the capacity of memoir to recognize the presence of these other-than-human agents that bear witness to the Anthropocene.

Although there is a distinctive arboreal turn in this special issue, to phytography rather than animalography, we have argued that a focus on the Anthropocene in life writing more generally is haunted by its definitive awareness of death. To return once again to Laurent’s Flora: Exploration to Extinction, the arts and scholarship of the Anthropocene address death and extinction, the powers of grief and mourning, and the precarity of zoe—life generally considered so insignificant as to be killable. Grace Moore’s essay on “animalographies, kinship, and conflict” turns to the history of the emotions, and representations of animal emotions in particular. In her reading of two animalographies—Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals, a collection of ten stories featuring an animal recounting the circumstances of its death, speaking from the afterlife, and Eva Hornung’s Dog Boy, the fictionalized biography of an abandoned child who assimilates into a dog pack—Moore considers an important ethical issue in critical debates about animalographies (and, it follows, phytography): the projection of emotions onto other-than-human life and the propensity to turn to human rights discourse to recognize and empathize with these “living things that have no rights” (to return to Leunig once more). Animals and plants are rendered expendable, property to be “managed” and “farmed,” and these animalographies focus on the “vexed question of who is kin and who is food”.41 The distinctions between which animals are “livestock” and which are “companions” are historical, cultural, and (in times of scarcity) subject to change. “[T]he primacy of the so-called civilized human animal over all others signifies a failure of empathy that now threatens to undermine all forms of life in the Anthropocene”.42

This turn to the emotions and to empathy in the Anthropocene sets the stage for the essays in The Forum, and each of these confronts the reader by focusing on the ethics of human jurisdiction over the lives of other-than-human animals, whether this be through breeding and slaughter or for sport and curiosity in colonial times. In “Writing the Cow: Poetry, Activism, and the Texts of Meat,” Jessica Holmes returns to Carol J. Adams’ writing on “texts of meat” and the emerging field of vegan poetics to consider the ethics of interspecies relations in the Anthropocene. What does it mean to “write” the life of a cow? Here, too, the question of empathy and “bearing witness” to the suffering of other-than-human life returns as a key issue for thinking on life writing in the Anthropocene and, in response, Holmes argues for the reparative potential and the logic of care, rights, and responsibilities of vegan poetics. Barbara Holloway also contemplates the strained relationship between the domestic animal reared as a poddy lamb in the kitchen and the flock animal sent to slaughter. Drawing on E. O. Schlunke’s Stories of the Riverina, she considers how the subjectivity of a flock animal might be written, particularly in a way that draws attention to its exploitation. Rick De Vos’s contribution to this Forum is both literary and visual, and draws this special issue back to where we begin with Flora: Exploration to Extinction. De Vos’s essay focuses on two specific historical acts of killing: a platypus near Ravenshoe, Queensland, in September 1921, and a Yangtze River dolphin in Hunan Province in February 1914. The collection of skulls of species at risk of extinction for display in the US National Museum of Natural History by Charles McCauley Hoy presents a conundrum: fear of species extinction leads to the mission of collecting, which risks making the threat of extinction manifest. De Vos turns to animalography to translate these killings from the perspective of the animal, in juxtaposition with the account in Hoy’s field notes. He also includes three figures: images of the specimens in the museum collection and the catalogue records of these skulls. This special issue begins to close, then, as it begins - immersed in images of extinction - before making a segue to Stephen Muecke’s biography of Deborah Bird Rose. Muecke, reflecting on Rose’s gift of storytelling, reminds us that “stories, articulated with time that passes, are a good device for teaching and learning.” Stories in the Anthropocene can teach us to be aware of, and how to interact respectfully with, the other-than-humans with whom we share our world.

There is an Antipodean turn in this special issue, and we complete this work on “Life Writing in the Anthropocene”—which time and again returns to “death on an unimaginable scale43—at a place and time where life writing and criticism is intimately connected to everyday life, as it so often is. Fire surges on an unprecedented scale here in the summer of 2019–2020; the term “catastrophic” has never been used so often. Rainforests burn; eucalypts explode and release pungent flammable fumes. Embers fly many kilometers ahead of the fire fronts, which consume human, other-than-human animal, and plant life. Also catastrophic and historical is the drought-induced mass death of other-than-human life. In the summer of 2018–2019, up to a million native Australian fish, including Murray cod decades of years old, were killed in three separate incidents in the Darling River, a major waterway stretching across the state of New South Wales. We see “fish kill”—thousands of silvery bodies floating on the surface of a river—and listen to descriptions of the choking smell of rotting fish. The magnitude of these events is extraordinary. In times like these, where the logic of commodification and denial rules, the relevance of scholarly work in the humanities is subject to question.44 Here, in this special issue, critical and creative writing and artworks on life narrative rise to the challenge of the Anthropocene in theory and practice. We are drawn into corridors where portraiture, ecobiography, phytography, obituary, stereometry, thanatography, testimony, and animalography bear witness to a multitude of lives and deaths.

The University of Queensland

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the generosity of both Anna Laurent and Michael Leunig in allowing us to reproduce their images, which trigger our reflections in this special issue.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Laurent, Flora.

2 Laurent, Flora.

3 Ryan, “Writing the Lives of Plants,” 97.

4 Cooke, “Writing Toward and With,” 63.

5 Huff, “Autobiographical Pact.”

6 Whitlock and Couser, “Post-ing Lives.”

7 Rose, “Slowly,” 2.

8 Douglas and Barnwell, Research Methodologies, 32.

9 Huff, “Autobiographical Pact,” 446.

10 Steffen et al., “The Anthropocene.”

11 Crutzen and Stoermer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” 17.

12 Zalasiewicz, Williams, and Waters, “Anthropocene,” 15.

13 Bradley, “Writing on the Precipice.”

14 Wilson, “Beware.”

15 Crutzen and Stoermer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” 17.

16 Haraway, cited in Huff, “Autobiographical Pact,” 445.

17 Leunig, “Tree.”

18 Smith and Schaffer, Human Rights, 32.

19 Nils Bubandt, cited in Joutseno, “Becoming D|other,” 86.

20 See Rose, “Slowly.”

21 Bristow’s essay is also in memory of Heather Kerr, a researcher in the “History of the Emotions” project with a particular interest in botanical life. The influence of this major Australian Research Council project is also acknowledged in Moore’s essay on animalography in this issue.

22 Bristow, “Period Rhetoric, Countersignature, and the Australian Novel,” 55.

23 Cooke, “Writing Toward and With,” 75.

24 Cooke, “Writing Toward and With,” 64.

25 Cooke, “Writing Toward and With,” 72.

26 Rose, Nourishing Terrains, 7.

27 Rose, Nourishing Terrains, 10.

28 Joutseno, “Becoming D|other,” 82.

29 Joutseno, “Becoming D|other,” 83.

30 Joutseno, “Becoming D|other,” 86.

31 In the preceding issue of a/b: Auto/Biography Studies on “Engaging Donna Haraway: Lives in the Natureculture Web,” Margaretta Jolly’s essay “Survival Writing: Autobiography versus Primatology in the Conservation Diaries of Alison Jolly” is written in tribute to her mother.

32 Muecke, “Her Biography: Deborah Bird Rose,” 274.

33 Muecke, “Her Biography: Deborah Bird Rose,” 274.

34 Muecke, “Her Biography: Deborah Bird Rose,” 274.

35 Ryan, “Writing the Lives of Plants,” 101.

36 Connor, “‘If a Tree Falls…’,” 124.

37 Harley, “Writing the Lives of Fungi,” 146.

38 Krieg, “Planetary Delta,” 162.

39 Krieg, “Planetary Delta,” 166.

40 Hughes-d’Aeth, “Memoir and the End of the Natural World,” 201.

41 Moore, “'As Closely Bonded as We Are'," 214.

42 Barbara Creed, cited in Moore, “'As Closely Bonded as We Are'," 223.

43 Cooke, “Writing Toward and With," 63.

44 Attenborough, “It’s Extraordinary.”

Works Cited

- Attenborough, David. “It’s Extraordinary Climate Deniers Remain in Australian Politics.” The Guardian, July 7, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/global/video/2019/jul/10/david-attenborough-its-extraordinary-climate-deniers-remain-in-australian-politics-video

- Bradley, James. “Writing on the Precipice.” Sydney Review of Books, February 21, 2017. https://sydneyreviewofbooks.com/writing-on-the-precipice-climate-change

- Bristow, Thomas. "Period Rhetoric, Countersignature, and the Australian Novel." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 35–62.

- Cooke, Stuart. "Writing Toward and With: Ethological Poetics and Nonhuman Lives." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 63–80.

- Connor, Eamon. "'If a Tree Falls …' : Posthuman Testimony in C. D. Wright’s Casting Deep Shade." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 123–144.

- Crutzen, Paul J., and Eugene F. Stoermer. “The ‘Anthropocene.’” IGBP Newsletter, no. 41 (2000): 17–18.

- Douglas, Kate, and Ashley Barnwell, eds. Research Methodologies for Auto/biography Studies. New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

- Harley, Alexis. "Writing the Lives of Fungi at the End of the World." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 145–160.

- Huff, Cynthia. “From the Autobiographical Pact to the Zoetrophic Pack.” a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 34, no. 3 (2019): 445–460.

- Hughes-d'Aeth. "Memoir and the End of the Natural World." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 183–206.

- Jousteno, Astrid. "Becoming Djother: Life as a Transmuting Device." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 81–96.

- Kilmer, Joyce. “Trees.” Poetry 2, no. 5 (1913): 160.

- Krieg, Parker. "Planetary Delta: Anthropocene Lives in the Blues Memoir." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 161–182.

- Laurent, Anna. Flora: Exploration to Extinction. https://www.annalaurent.com/flora-installation

- Leunig, Michael. “Tree.” March 8, 2014. https://www.leunig.com.au/works/recent-cartoons/463-tree

- Moore, Grace. "'As Closely Bonded as We are': Animalographies, Kinship, and Conflict in Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals and Eva Hornung’s Dog Boy." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 207–230.

- Muecke, Stephen. "Her Biography: Deborah Bird Rose." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 273–278.

- Ryan, John Charles. "Writing the Lives of Plants: Phytography and the Botanical Imagination." a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 35, no. 1 (2020): 97–122.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. Nourishing Terrains: Australian Aboriginal Views of Landscape and Wilderness. Canberra, NSW: Australian Heritage Commission, 1996.

- Rose, Deborah Bird. “Slowly—Writing into the Anthropocene.” TEXT, no. 20 (2013): 1–14.

- Smith, Sidonie, and Kay Schaffer. Human Rights and Narrated Lives: The Ethics of Recognition. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Steffen, Will, Jacques Grinevald, Paul Crutzen, and John McNeill. “The Anthropocene: Conceptual and Historical Perspectives.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 369, no. 1938 (2011): 842–867.

- Whitlock, Gillian, and G. Thomas Couser. “Post-ing Lives.” Biography 35, no. 1 (2012): v–xvi.

- Wilson, Edward O. “Beware the Age of Loneliness.” The Economist, November 18, 2013. http://www.economist.com/news/21589083-man-must-domore-preserve-rest-life-earth-warns-edward-owilson-professor-emeritus

- Zalasiewicz, Jan, Mark Williams, and Colin Neil Waters. “Anthropocene.” In Keywords for Environmental Studies, edited by Joni Adamson, William A. Gleason, and David N. Pellow, 14–16. New York, NY: New York UP, 2016.