Abstract

The article traces how understandings of the concept of autofiction have developed between 2000 and 2020. It observes a broader, and more global, understanding of autofiction as well as an other-, reality-directed and ethical turn. The article links these developments to terminological changes and twenty-first-century conversations around identity and representation.

Autofiction is a contested and arguably flawed term, popularized by Serge Doubrovsky in the 1970s, that has nonetheless taken root in the academic and more general vocabulary.Footnote1 It is typically used to refer to a group of contemporary texts that combine fictional and autobiographical modes, yet even this description, despite its extreme openness, might not find consensus agreement. Initial discussion of the term and the practice associated with it took place largely in French and concerning French literature,Footnote2 but the beginning of the new century has seen a rapid increase in critical attention in the Anglophone sphere, which has brought with it important conceptual developments. These developments are the subject of this article, which charts trajectories of critical thinking on autofiction as term and concept in Anglophone criticism from 2000 to 2020.

Our findings derive from an online word-search project on the use of the term “autofiction” in articles, e-books, and theses published in this twenty-year period.Footnote3 These data were collected in 2021 using Bodleian Libraries’ search tool SOLO, Search Oxford Libraries Online. Subscribed to the Primo Central Index, which gathers data from many of the same publishers as Google Scholar, SOLO provides access to thirteen million library items and three million Electronic Legal Deposit e-books and journal articles across different languages, including non-Roman scripts. It supplements this index with publications available through university subscriptions and articles and theses held in the Oxford Research Archive, and it provides full access to all search results. We compiled year-by-year bibliographies, which included every work in which the term appeared across different languages, before concentrating in depth on the Anglophone results and combining quantitative and qualitative analysis to evaluate developments in the discourse on autofiction. Our quantitative questions focused on three key areas relating to the primary works that the author had considered under the label: the linguistic and national contexts in which they were written and publishedFootnote4; the form or medium, if other than long prose text; and the date of publication, where this preceded the popularization of the term from 1977. The final primary research question was qualitative and assessed whether the author had used the term reflectively. Our criteria for determining this “critical engagement” were that the author considers debates around and developments in understandings of the term, thus demonstrating awareness of definitions beyond Doubrovsky’s 1977 conception, and/or that she or he explains and reflects on the implications of the particular approach to autofiction they adopt in their analysis. In addition, we investigated notable patterns, for example, between the contexts in which adjectival forms are used in place of the noun and conceptions of autofiction as a genre, mode, form, strategy, or other descriptions. By identifying and analyzing tendencies that emerged, first within and subsequently between three-year intervals, we traced the trajectory of the term in Anglophone discussions.

If a consensus on autofiction can be discerned, it is the agreement that no consensus will be reached and that open, diverse, divergent, and continuously changing understandings are of value. Armine Kotin Mortimer is the first critic in this study to identify this paradoxical consensus as the cornerstone of the discussion, and the most emphatic: from it, she argues, stems a “collective will to blur the boundaries of the genre as much as possible” and “the more fluid the definition, the happier the collective thinking is.”Footnote5 Natalie Edwards emphasizes autofiction’s “necessary resistance to definition” even as she observes that it is also what “awards its opponents an easy target” in debates on literary value,Footnote6 and she and Mortimer are respective reference points for Amelia WalkerFootnote7 and Todd WombleFootnote8 when they take up the discussion of the “productive” lack of consensus in their respective chapters in Autofiction in English. Indeed, Dix identifies “the recognition that there is no single definition of autofiction either in English or in French” as one of the vital starting points for the first book-length study of Autofiction in English.Footnote9 This recognition, we argue, has played a vital role in the wider development of thinking on autofiction in Anglophone criticism, and its impact on the term and concept merits further investigation.

Our findings indicate that as the term becomes established in the Anglophone discussion, understandings of autofiction shift toward seeing it as a global practice, not confined to a particular language, geographical, national, or cultural context, or to a particular medium, and as less concerned with the individual than with selves about others and the world at large. The critical (re)thinking behind this outlook, as this article argues, is closely linked to the terminological tendencies of this discussion, as well as to broader changes in the socio-cultural sphere. In the first part, we explore how critical trajectories surrounding terminology have allowed for a broader, including a more global, understanding of autofiction, and one ranging across diverse media. In the second part, we consider shifts in the discussion of life writing since the turn of the millennium, in response to conversations around identity, self-representation, and ethics and aesthetics. Our data show what one might call an other-, reality-directed, and ethical turn in the discussion of autofiction.

Expanding Critical and Conceptual Parameters: Thinking with Terms

Terminology affects our way of thinking. As Terence Cave observes, by way of the example of the heuristic value of the word affordance,Footnote10 the use of a specific term can promote “a redescription of familiar aspects of, or issues in, literary analysis,” and thereby make for a “shift of angle” that, “may be relatively slight, but nevertheless critical.”Footnote11 He stresses that “[a] new set of ideas cannot be assimilated by methodical or methodological accumulation alone,” but needs “an instrument that makes a difference, a vehicle that can take you further,” an affordance, in other words, which is etymologically linked to the adjective and verb (to) further.Footnote12 Whether we say (and think) “autofiction” or “autofictional,” can thus make a crucial difference in terms of the texts to which we turn our attention. Simply put, if we speak (and think) of autofictional strategies or modes, we are more likely to find these in a text that would not qualify as autofiction according to narrower definitions of the term. Shifts in terminology affect shifts in angle and focus that can take us further, for example, toward seeing autofiction as a global practice, and also as less, or not predominantly, concerned with the self.

These terminological affordances emerge clearly in our data as we consider the changes in the use of the term in the Anglophone conversation alongside developments in our understanding of what autofiction means and our expectations of what it will look like. As Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf observes in a comment on the discussion on autofiction as a term, critical thinking works by perpetually reconsidering terminology,Footnote13 and this is what the evolution of the Anglophone discussion confirms. Formulations such as “autofictional texts,” “autofictional writing,” and “autofictional narratives” are common from the outset, and the preference for the adjective becomes increasingly evident. While this choice receives little explicit comment, and there remains slippage between the adjective and the noun in expanded understandings of autofiction, the use of “autofictional” in context makes evident that it accompanies and enables a more pliable understanding of the practice. Cognitively, it affords a more flexible conceptualization, one which facilitates, in turn, increasingly frequent and diverse applications to works in different languages, from different nations and in different media.

This more flexible conceptualization is facilitated by a shift away from the focus on taxonomy that predominates in early studies of autofiction, particularly in France. Doubrovsky developed his understanding of autofiction in response to Philippe Lejeune’s Citation1975 study Le pacte autobiographique, which differentiated autobiographical and fictional writing based on the shared identity of author and protagonist: onomastic correspondence, Lejeune argued, seals a pact with the reader to tell the truth. According to his structural classification, a work that features this shared name but declares itself to be fictional would be a contradiction in terms,Footnote14 and the combination thus forms an empty square in the table of autodiegetic narratives he designs. Doubrovsky lays claim to precisely this co-existence of autobiographical and fictional pacts, of course, when he labels Fils, with its protagonist named Serge Doubrovsky, a “novel.” He writes in “Autobiographie/Vérité/Psychanalyse” (1980) that the intention behind the work was to fill said square and in so doing, as Alison James observes, he “undermines the pragmatic basis of Lejeune’s distinctions.”Footnote15 The dominant conception of autofiction originates, in other words, in a theoretical clash over the classification and delimitation of autodiegetic narratives and these questions of taxonomy determined the study of autofiction as it developed in France. Joost de Bloois goes so far as to describe this as “the French debate”: he argues that the “rewarding or withholding of autofiction’s genre credentials” has “long dominated the character and quality of the discussions.”Footnote16

Certainly, the matter of how we might categorize autofiction is the main current of the major theoretical interventions in the French context, as critics including Doubrovsky, Lejeune, Jacques Lecarme, Marie Darrieussecq, Vincent Colonna and Philippe Gasparini grapple with how narrowly the term should be defined and applied. Of these critics, Colonna goes furthest in transforming the approach to taxonomy. His argument that autofiction defies such categorization and challenges notions of genre is accompanied by an encompassing conception of autofiction as a practice of literary self-invention, or autofabulation.Footnote17 Colonna proposes a new typology intended to resist the rigid classifications that, from his perspective, cannot accommodate autofiction, while maintaining a productive theoretical coherence. This expanded understanding has become an important springboard for scholars in different linguistic contexts who seek to widen further the parameters of autofiction. In the Anglophone sphere, broader conceptions of what autofiction is and what it can designate, employed with varying levels of critical engagement and precision, have drawn the focus of much of the discussion away from taxonomy. For critics such as de Bloois, this is a conscious change of direction.Footnote18 In the introduction to his 2007 special issue on visual autofiction, he makes explicit the impetus behind his critical rethinking of the concept, namely, that attempts to categorize and taxonomize have “clogged” the study of literary autofiction.Footnote19 To move away from such attempts and think of autofiction instead as an assemblage of strategies—a starting point de Bloois takes from Colonna—affords an understanding of the concept as not limited to one particular genre or medium. The major impact of this special issue on expanding the range of media we associate with autofiction shows the productiveness of this rethinking.

The connections between these changes in conceptual focus, terminology, and critical rethinking become evident early in our dataset. While in 2000 and 2001, the majority of Anglophone works refer unreflectively to autofiction as a genre, 2002 marks the first explicit engagement with the contested description of autofiction; an intervention that proposes the move away from the genre descriptor. Alex Hughes asks whether autofiction constitutes a genre in its own right, or whether it is a sub-genre of autobiography. Focusing on textual strategies, she proposes that autofiction is understood most helpfully as a narrative modality, one which weakens the borders between genres. Marion Sadoux, too, makes the case for understanding autofiction as a mode. She does so with a focus on reception, namely by taking up Marie Darrieussecq’s account of autofiction as willed ambiguity. Sadoux thus focuses on the specific, uncertain mode of reading that autofictional texts posit. Even while the move to adjective has not yet occurred in these instances, both Hughes and Sadoux refocus attention to textual qualities and readerly engagement. Whether their emphasis on these aspects leads to terminological reconsideration or vice versa is difficult to establish, and the attempt to do so is ultimately unproductive. The process should rather be seen as circular, with cross-transfers between the aspects on which one focuses and the terminology one thinks with and through.

Hughes’s article becomes a key point of reference in the Anglophone discussion and what we see develop in the years following this publication is increasing critical reflection on or problematization of the description of autofiction as a genre. From 2005, such descriptions are often accompanied by qualifiers such as “hybrid,” “unstable,” and “paradoxical,” or occasionally placed in inverted commas, to convey what they see as the resistance of autofictional texts to such classification.Footnote20 Several critics follow Hughes in understanding autofiction as a mode,Footnote21 but more notable is the diversity in descriptions of autofiction in the Anglophone discussion. Like critics who speak of autofiction as a mode, studies that approach it as a form,Footnote22 or as a sub-genre or division of autobiography,Footnote23 seem to think of the term as denoting a quality that can form part of many genres and that might even occur outside the realm of art. The same implication is present, perhaps even more strongly, in descriptions of autofiction as a strategy,Footnote24 and in broader explanations that tend toward adjectival understandings of autofiction rather than perceiving it as a genre label: examples include a postmodernist or literary trend,Footnote25 and various blends or mixes of fact, memory, and personal history with fiction and imagination.Footnote26

The trend toward understanding autofiction adjectivally, whether the adjective is actually used or not, continues subsequently. The year 2011 sees a discernible shift away from applying the term as a genre marker; it is instead qualified as one possible category for a work (together with others),Footnote27 as describing some characteristics of a given work,Footnote28 or as one element working in combination with other genres, modes, media, and strategies.Footnote29 This shift is evident as adjectival formulations diversify and proliferate—“autofictional projects,” “autofictional practices,” and “autofictional strategies” are three of the most frequent—Footnote30 but also when critics describe authors as adopting a more distanced, tentative, or self-reflexive position in relation to autofiction as genre.Footnote31 The preference for and range of these partial applications is most evident in 2017: Gergely Kunt, Karl Agerup, and Mike Frangos all portray autofiction as one categorization of or approach to the texts they discuss; Nicoletta Mandolini categorizes Maria Schiavo’s Macellum as a combination of autofiction and the anthropological essay; and Massimiliano L. Delfino and Judith Still both opt to compare the works they analyze to autofiction, rather than to classify them as such.Footnote32 All these partial applications, which direct our attention to autofictional elements, features, or qualities, contribute to the turn away from using autofiction as a genre label in the Anglophone discussion, and toward emphasizing autofictional qualities within or in combination with other genres. These developments appear to increase alertness to autofictional phenomena in a wider range of works. In particular, the change from exclusive use of the noun (autofiction) to adjectival forms seems to have led to a shift in critical focus that has enabled an understanding of autofiction as global practice.

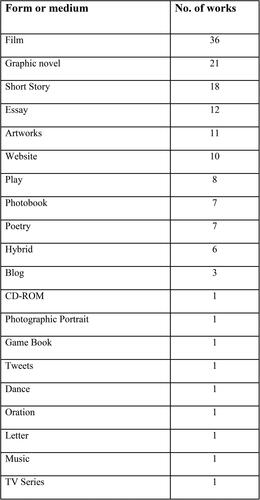

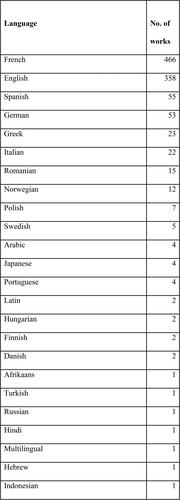

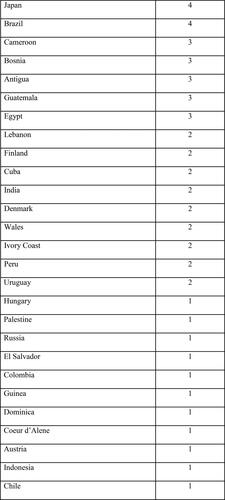

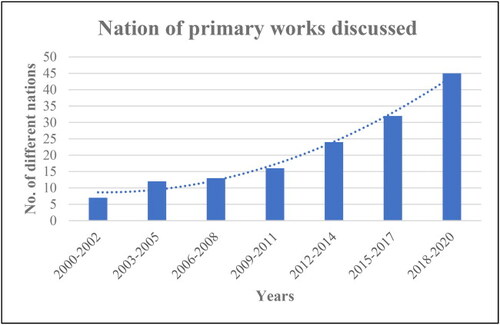

As autofiction properly enters the Anglophone conversation in 2001, with Johnnie Gratton’s entry on the term in Margaret Jolly’s Citation2001 Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Writing,Footnote33 we see a rapid spread in the languages, nations, and cultural contexts that are considered. Our data shows moreover a similar widening of the concept to include forms other than the long prose text and to encompass different media. The number of languages of primary works that are discussed under the umbrella of autofiction (see ) increases in all but one three-year period (there is a slight dip in 2006–08, in which the total number of languages is one lower than in 2003–05), going from three languages in 2000–02 (French, English, and Arabic) to sixteen languages in 2018–20 (see and in the appendix for the breakdown of works in each language). French works rank highest, amounting to 44.8% of the titles discussed, and English comes second with 34.3%, followed, after a significant drop, by Spanish (5.3%) and German (5.1%). Greek and Italian have a 2.2% and 2.1% share respectively, and Romanian and Norwegian make up 1.4% and 1.2% of the results. The remaining 16 works comprise less than 1% of the results, with the following distribution: Polish (0.67%); Swedish (0.48%); Arabic, Japanese, and Portuguese (0.38%); Latin, Hungarian, Finnish and Danish (0.19%); and Afrikaans, Turkish, Russian, Hindi, Hebrew, and Indonesian each appear only once in the results, along with one work classed as multilingual.Footnote34

Figure 1. Bar chart showing the total number of different languages of the primary works discussed in each three-year period of our study.

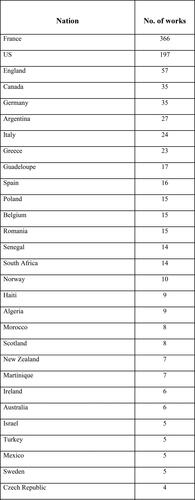

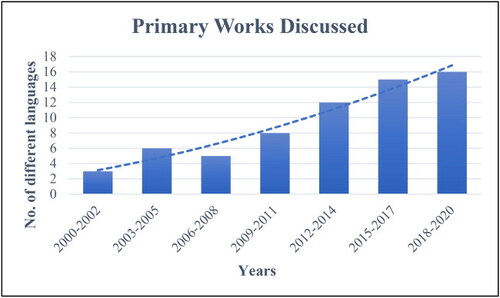

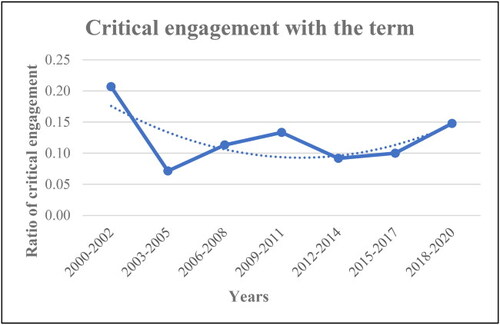

The number of nationsFootnote35 from which the primary works in our data set are taken (see ) shows a similar pattern, rising continually in every three-year period from a range of seven nations in 2000–22 to forty-five nations in 2018–20. Increments increase steadily with the largest rise between 2015–17 and 2018–20; this peak is produced in part by the 2019 publication of Martina Wagner-Egelhaaf’s Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction, which explicitly adopts a global approach. The works discussed stem from a total of fifty-six different nations (see in the appendix): France has the highest number of results by a considerable margin, boasting over 36% of the primary works discussed, and the US, with almost 20%, the second highest. Next are England (5.7%), Canada and Germany, which each have a 3.5% share of the results. Argentina, Italy, Greece, Guadeloupe, Spain, Poland, Belgium, Romania, Senegal, South Africa, and Norway (in descending order) contribute over a 1% share of the primary works. Forty-one further nations feature, and, although the bulk of primary works remains concentrated in the Francophone and Anglophone spheres, this range attests to an increasingly global spread.

Figure 2. Bar chart illustrating the total number of different nations from which the primary works discussed are taken in each three-year period of our study.

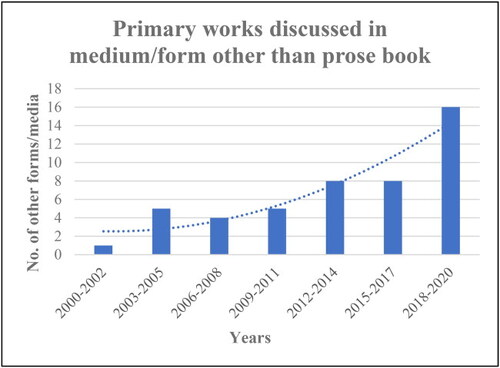

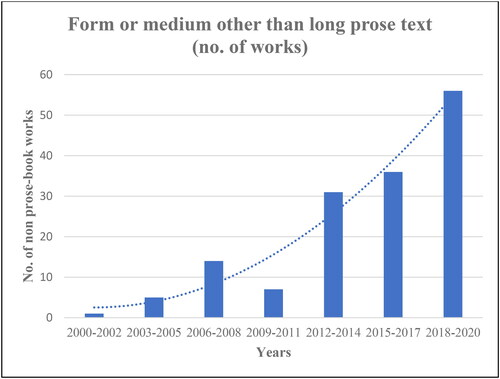

The diversification of primary works described as autofiction or autofictional in this twenty-year period also extends to forms and media (see ). The total number of works in a medium or form other than long prose text rises from one in 2000–02 to fifty-six in 2018–20. Twenty different media or forms are discussed under the label in total in this study (see in the appendix): film is the most common, with 24% of the results, followed by the graphic novel, which has a 14% share, and the short story, with 12%. Essays make up 8% of the results, artworks 7.3%, and websites 6.7%. Plays, photobooks, and poetry are the next most common media, hybrid works and blogs comprise 4.7% and 2% of works respectively, and there is one work from each of the eight remaining forms and media.

Affordances and Constraints of Broader Terminology

While we see the global spread and widening consideration of medium in the discussion of autofictional phenomena as afforded by the terminological developments charted above, affordances are always accompanied by constraints. Bloom observes that “[w]here the competing, hyper-specific viewpoints on these topics make it difficult to arrive at one coherent definition of autofiction […], Anglophone critics are beset by the opposite problem: namely, that the variety of works unproblematically grouped under the label—works from different periods, genres, styles, and even media—necessitates a broad conceptual rubric.”Footnote36 Thinking autofiction adjectivally affords new understandings of autofictional practice and allows a more inclusive perspective, but this breadth also raises issues concerning classificatory rigor and critical engagement. Doubrovsky himself declared Colonna’s assimilation of autofiction into his theory of autofabulation to be an “abus inadmissible” (unacceptable misuse [of the term])Footnote37 and emphasized the danger of this loss of specificity, too, when autofiction is confused with the autobiographical novel. These pitfalls are also articulated in the Anglophone context and the shift away from establishing and narrowing the parameters of the term leads at intervals to definitions that critics have deemed unhelpfully broad. Stavrini Ioannidou echoes Doubrovsky’s concerns, for example, when she argues that autofiction is reduced to a “vague mot-valise” term if we apply Colonna’s typologyFootnote38; Kristina Pla Fernández discusses the misinterpretations and miscategorizations of fictional and testimonial texts that have arisen from readers’ failure to differentiate between autofictions and autobiographical novelsFootnote39; and Max Saunders summarizes that the term is “used to describe such a wide range of autobiographical fiction that it is in danger of losing the very analytical clarity it was introduced to provide.”Footnote40 Often in this study, however, when critics comment on the lack of consensus or stability around definitions of autofiction, they perceive its malleability in a positive light. Mortimer observes as far back as 2002, as we have seen, that the collective impetus in thinking about autofiction is toward as fluid an understanding as possible, even as she acknowledges that the broad application has given the term “depth without sharpness.”Footnote41 Dix attributes the burgeoning critical interest in autofiction to its multiple different theories and definitionsFootnote42 and Edwards (Citation2014), Morven Fraser (Citation2015), and Walker (2018) are among the most vocal in championing the freedom that this resistance to fixed interpretations affords authors and scholars alike.

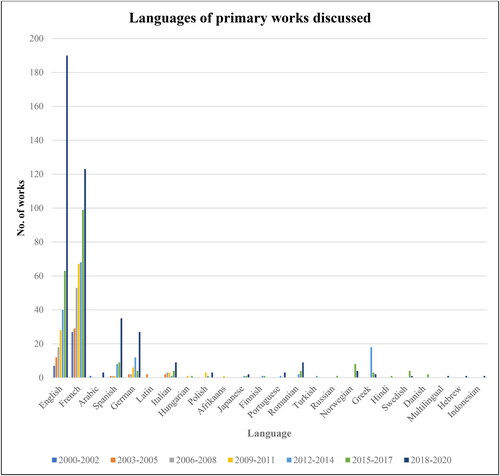

If the “clarity” and “sharpness” of definitions dissolve, like Saunders and Mortimer suggest, as the use of autofiction expands, this does not necessarily make for an unreflective consideration of the term and concept. The graph below (see ), which traces the ratio of works that engage with the term critically over three-year periods, demonstrates that there is no linear correlation between the overall progression in the discussion toward a broader and adjectival conceptualization and a less reflective use of the term.

Figure 4. Line graph showing the ratio of secondary works that engage critically with the term ‘autofiction’ in each three-year period of our study.

The ratio of works that use the term “reflectively” is at its highest in the period 2000–02, when the term is less familiar in the Anglophone sphere.Footnote43 It drops to its lowest level in 2003–05, after the term is consolidated in the Anglophone conversation by key works published in 2002 (notably, Alex Hughes, “Recycling and Repetition in Recent French “Autofiction”: Marc Weitzmann’s Doubrovskian Borrowings,” which becomes the most prominent Anglophone point of reference across the period). Multiple broad applications of the term are subsequently employed as the works discussed begin to diversify in terms of language, nation, and period. Critical engagement begins to rise again in 2006–08 and continues to do so until 2009–11. From 2009 onwards, the breadth of application of the term itself becomes an important source of critical engagement. If we compare two of the most influential articles from 2009 and 2010 respectively, by Armine Kotin Mortimer and Arnaud Schmitt, we see a different, but no less reflective, debate emerge in the Anglophone sphere compared to the taxonomic focus of the Francophone one. Mortimer, in “Autofiction as Allofiction: Doubrovsky’s L’Après-vivre” (2009), and Schmitt, in “Making the Case for Self-narration Against Autofiction” (2010), adopt opposite stances in relation to the liberal application of the term. While Mortimer claims that any consensus definition has become impossible and that momentum is toward blurring boundaries of the “genre” through flexible definitions, Schmitt argues that the question of genre still needs to be settled and proposes replacing the term “autofiction with” “self-narration” to do so. Tracing the Anglophone conversation through 2011–20 leaves no doubt that it pulls strongly in the direction that Mortimer outlines; that is, accepting and privileging the malleability of the term. After a dip in the ratio of critical engagement in 2012–14, we see a continuous rise, and critical engagement with the term returns to its highest level since 2000–02 in 2018–20. The publication of Autofiction in English and the Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction contribute to this spike, but the reflective use of the term in these volumes is part of a much wider critical engagement in other book-length studies, articles, and theses in these years.

Intellectual engagement is by no means constrained, this data shows, as the discussion in the Anglophone sphere puts the accent on broad (and broadening) parameters of autofiction.Footnote44 It indicates that these shifts have instead opened up alternative ways in which to reflect critically on the term, a hypothesis consolidated by the more flexible understanding of autofiction that has driven new conceptual work undertaken since 2020.Footnote45 The shift away from delimiting the term, in sum, by no means shuts down the conversation; rather, it invites and facilitates further investigation in multiple different directions. Certainly, it is at least in part thanks to the expanded conception of autofiction that different languages, nations, media, and time periods enter the discussion.

Thus far, the argument made in this article may seem to be that the broader the terminology, the better we see wide-ranging autofictional phenomena. While this is true to an extent, more inclusive approaches to the term do not have to exclude additional categorization, which brings its own affordances. This is evident already from Colonna’s “big-tent” typology, which particularizes four varieties of autofiction. How such supplementary terminology can allow us to see certain kinds of autofictional phenomena more effectively is apparent in the discussion of different forms and media in our corpus, where distinct terms serve to establish specific characteristics.

As we see in in the appendix, there is a significant peak in the number of works in different forms and media discussed as autofictional in the period 2006–08 (a jump to fourteen works from five in 2003–05) that marks the publication of the influential special issue in which de Bloois coins the term “visual autofiction.” de Bloois acknowledges intersections with literary autofiction but proceeds to differentiate visual autofiction on the basis of the specific artistic concerns and needs to which it responds. Isabelle Vanderschelden (Citation2012) subsequently adopts a similar approach to de Bloois in drawing out the specificities of the form when she argues that “film autofiction” is a self-standing cinematic genre, and Jenn Brandt (Citation2014) focuses on the departure of what she calls “graphic autofictions” from “traditional autofiction.” The latter term is embedded in the critical conversation by 2017, when Candida Rifkind uses it in her discussion of graphic life narratives without further explanation, and when Olga Michael takes it up in the following year in her chapter of Hywel Dix’s Autofiction in English. While Michael draws on Brandt’s coining of the term, she does not continue the focus on its specificities but looks instead to how the hybrid medium “accommodates” what she describes as the genre of autofiction.Footnote46 Autofiction in English contributes significantly to the spike in the number of works in a different medium or form in 2018–20. The increasing diversification in forms and media discussed under the label owes not only to the broader terminology that affords more flexible thinking about the practice, therefore, but also to the use of supplementary terminology and classifications.

The affordances of additional terminology for subcategories invite further reflection on what it means to consider the global reach of autofictional practice. Do we need, for example, the term “global autofiction,” or terminology that centers our attention on specific regions and languages? Should we speak of “Western autofiction” as opposed to, or as part of, “global autofiction”? Is there something like European, North American, South American, Asian, African, and Australian autofiction, or perhaps a distinct autofictional tradition of the Global South? And do we need precise terms that afford consideration of the practice in these regions? Would such terms help us see specificities? Would they constrain the attention we pay to overarching characteristics and concerns?

Anglophone Responses to Autofictional Practice in Twenty-First Century Contexts

As de Bloois suggests, the shift away from attempting to categorize autofiction seems to enable the discussion to move more freely in other directions. Broadly speaking, the Anglophone discussion turns its attention away from pinning down what autofiction is—that is, how we should classify autofiction, and where we are justified in applying the term—and toward what autofiction does, or what it can do. This turn does not only “unclog” debates around taxonomy, therefore, but also facilitates new approaches to long-standing questions over egocentrism and veracity, and sheds light on links between autofictional practice and twenty-first-century socio-cultural developments. Below, we outline some of the principal tendencies that emerge in the Anglophone discussion and explore the connections between our data and current developments in how twenty-first-century culture reconceives identity, reinvents forms of (self-)representation, innovates forms of testimony, rethinks concepts of truth, and explores new links between ethics and aesthetics.

By rethinking autofiction adjectivally, as a mode or strategy, or as one element of a work in combination with others, we are arguably more prone to perceiving it as less exclusively concerned with the self. The view of autofictional practice as a part of or in the service of something broader—a means or a tool, in other words, rather than an end—resituates debates on its literary value. A handful of studies describe autofiction as egocentric or exhibitionistic—Charles Forsdick (Citation2006); Simona Barello (Citation2007); Violeta-Teodora Lungeanu (Citation2014); and Raffaele Donnarumma (Citation2015)—but a strong defense is mounted against these accusations, especially in the years 2010 to 2020. de Bloois suggests that the emphasis on avatars in autofictional texts displaces autobiographical narcissism with new subjectivities, for example, and Karen Ferreira-Meyers (Citation2012) argues that autofiction privileges the role of the other in the construction of identity. Shirley Jordan (Citation2013), meanwhile, resists descriptions of Sophie Calle’s installation Prenez soin de vous as narcissistic based on Calle’s self-reflexive play with and critique of autofiction and the debates that surround it, while Dawn Cornelio (Citation2018) directs our attention to the social activism of Chloé Delaume’s autofictional writing to refute allegations that her works are egocentric. Teresa Pepe takes a similar tack when she observes that whereas “autofictional authors worldwide are often accused of exhibitionism and narcissism,” writing the body in the Egyptian blogs she analyses is a political act.Footnote47

The prevailing view in the Anglophone discussion is that the focus of autofictional works is far from limited to the writer’s self, and this general consensus is most evident in the number of studies that do not make the discussion or rebuttal of accusations of self-indulgence or navel-gazing their starting point. Examples include studies that focus on the collective dimension of autofictional practice: Renée Larrier (Citation2006) and Bonnie Thomas (Citation2017) argue that a range of Caribbean autofictional texts are driven by the desire to record collective memory, for example, and Yanbing Er (Citation2018) sees the representation of the individual in autofictional writing by North American women as serving to empower a collective female consciousness. Analyses of autofictional accounts of trauma also play a key role in moving the discussion away from questions of egocentrism: Rosa-Àuria Munté Ramos (Citation2011) describes autofiction as the means through which the writer-survivors of the Holocaust attempt to give voice to shared suffering, and Brandt (2012) argues in her study of graphic autofiction responding to 9/11 that the reflection on subjecthood and liminality in autofictional texts enables connection to others through narrative, and that it facilitates navigation between personal focus and national rhetoric. Broadly speaking, autofictional writing is conceived as more socially oriented than it has been in the Francophone context.Footnote48 It is notable that these reconsiderations of autofictional texts as ethically, politically, and other-directed rather than as primarily self-centered, stem often (although by no means exclusively) from critics who look beyond Anglophone and Francophone texts. That Ramos finds an ethical-political orientation in Spanish writer, Jorge Semprún’s work; that Pepe draws inspiration for a new understanding of autofiction from Egyptian blogs; that Brandt reconceptualizes the term as part of an exploration of differences between Francophone and global autofictional practice. The fact that Larrier and Thomas find collective memorial aims in the work of Caribbean authors Maryse Condé, Gisèle Pineau, Patrick Chamoiseau, Edwidge Danticat, and Dany Laferrière points to another kind or level of cognitive affordance, namely, the autofictional literary text itself. While an adjectival understanding of the concept increases the likelihood of finding autofictional elements in the aforementioned texts, these works afford, in turn, a reconceptualization of autofictional practice as more ethically and other-oriented.

An Other-, Reality-Directed, and Ethical Turn

Studies emphasizing that autofictional works relate the self to others, and the individual to the social, reconceive the practice as part of something wider, namely as responding and contributing to social, cultural, and political developments. It is reconceptualized as outward as opposed to (or as well as) inward facing, and not, therefore, as a freestanding exercise in experimentation or self-exposure. The Anglophone conversation leans strongly toward understanding autofictional texts as responding to wider questions about identity, subjectivity, and self-representation, and as a life-writing mode that facilitates connections between personal and national preoccupations. This understanding of autofictional practice becomes increasingly prevalent in the discussion as we approach 2020, and the links with the re-description of autofiction as a strategy become evident. “Strategy” appears frequently in studies where autofictional texts are analyzed as a means for challenging received or enforced narratives of identity, self-representation, and history: Mortimer (Citation2013) describes autofiction as one of the strategies employed in Assia Djebar’s work in response to unease with self-revelation in Arabic culture—a stark departure, of course, from indictments of autofiction, and women’s autofiction in particular, as exhibitionistic—Footnote49 and Sabine Ivenäs (Citation2017) considers autofictional texts by Scandinavian transnational and transracial adoptees as literary strategies in the negotiation of socio-cultural norms and debates (including gender, sexuality, race, family, immigration, and multiculturalism). Muge Salmaner (Citation2014) understands autofictional writing as a strategy for minority writers to speak about the past in the face of their dismissal from official history, and Gisli Vogler (Citation2019) identifies autofiction as one of the strategies employed in Herta Müller’s work to convey and maintain the ambiguity and complexity of life in Communist Romania, and so to cut through the closure and simplicity of narratives propagated by the totalitarian regime.

The attention to the social, cultural, and political affordances of autofictional texts in this discussion is certainly facilitated by the terminological developments we have seen, therefore, and the prominent recourse to “strategy” across the different chapters of Autofiction in English and the Handbook consolidate this impression. Reconceptualizations of autofiction as grounded in an activist agenda and engaged in specific historical-political contexts of oppression transverse the discussion of Djebar’s work as a response to Arabic cultural norms; transnational and transracial author identities (as in Astrid Trotzig’s Blod är tjockare än vatten [1996; translated as Blood Is Thicker Than Water], which engages with the author’s mixed Swedish and Korean identity); Armenian literature (discussed by Salmaner); and German immigration writing on Romanian personal and collective identity (Herta Müller). This current points to the affordances of global autofictional texts, in addition to that of the terminology used, in changing our thinking about term and practice.

What we can describe as the ethical turn in Anglophone discourse on autofictional practice and the progressive focus on global interrelatedness is also characteristic of twenty-first-century culture more broadly. Christian Moraru’s account of our contemporary period as characterized by increased concern with global relationality, and “solidarity across political, ethnic, racial, religious and other boundaries”Footnote50 offers further insight into the reconceptualization we have outlined. The sustained and progressive focus on how autofictional modes relate to wider social debates about ethics and aestheticsFootnote51 is linked, moreover, to the spotlight on personal narratives in the public sphere. Increasing attention is paid in this twenty-first-century context to the role of individual, and also contradictory, stories in current debates on identity—ethnic, national, and gender identity in particular—as well as on testimony, especially with respect to whom has been granted the right to speak and how this has determined the (hi)stories with which we live.

The turn of the millennium has also brought significant, related developments in how autofictional texts reconceive boundaries and links between fact and fiction, and the relations between lived experience, its representation, and elements of invention and imagination in both. Contemporary autofictional works, and critical responses to them, offer insight into current debates over descriptions of our times as “post-truth” or “post-factual.” The increasing recognition that truth is relative, and perception filtered, and the fact that we see autofictional phenomena where we did not previously, should not be equated with a belief that concepts of facts and truths no longer matter, as these descriptions may suggest. The complex engagement of twenty-first-century autofiction with these concepts of facts and truth is mirrored in critics’ numerous and diverse understandings of how autofictional work relates to veracity.Footnote52 While some critics perceive autofictional practice as resistant to or incompatible with notions of truthFootnote53 the more common viewpoint across the discussion is that autofictional texts offer insight into a different type of approach to truth. Multiple studies consider, for example, that the expression of emotional and subjective truths is the driving force for practitioners.Footnote54 Other critics focus on how readers’ relationships to “truth” are affected by autofictional works: some propose that autofictional texts prompt readers to seek the truth more actively or avidlyFootnote55; others argue, by contrast, that autofictional works highlight the impossibility of reaching a single “truth,”Footnote56 or force us to reconsider what we conceive of as truth-telling. What all these accounts indicate is that, as Alison Gibbons, Timotheus Vermeulen, and Robin Van Den Akker (2019) observe, accounts of autofiction as “a literary genre that seeks to get at truth and at reality” are gaining traction, although it should be stressed that autofictional texts rethink, sometimes radically, what kind this truth is and how it might be approached. This truth- and reality-oriented direction reinforces the focus on autofictional modes as response to social, political, and historical developments. Autofictional practice participates in conversations over what we understand by “truth” in a twenty-first century context in response to new media ecologies, in contexts of liberatory transformations of self, and as part of rejection of universal reason and prescribed, uniform meanings.

The advent of social media is one of the driving factors behind the “post-truth” description of the twenty-first century, and this digital context of identity construction has a prominent role in the Anglophone discussion throughout this study.Footnote57 Several studies engage directly with online autofictional practices or with texts that incorporate these modes of communication: prominent examples include Heidi Peeters (Citation2007), who explores MySpace as multimediatic autofiction; Pepe (Citation2019), who analyses Arabic autofictional blogs; Alois Sieben’s (2019) examination of the internet as a mode of self-construction or deconstruction in Megan Boyle’s Liveblog project; and Bloom’s special issue “Sources of the Self (i.e.)” (2019), which puts explorations of autofiction as an up-and-coming mode of production in the digital age into dialogue with studies which take autofiction as a lens through which to approach earlier texts. Many others reflect on the connections between autofictional practices and new media ecologies more broadly, with a view to the new perspectives on and insights into self-knowledge and self-representation offered by digital practices.Footnote58 The proliferating and often inconsistent narratives of selfhood and experience that are now so prominent in everyday life puncture impressions of identity as fixed and singular on a broad scale. As digital and online acts of identity construction draw attention to this self-staging and open up new avenues for exploring and expressing plural and shifting identities, longstanding tenets of autofictional practice gain in interest.

The discussion has emphasized in recent years, moreover, that the ways in which autofictional texts disrupt singular and stable truths have a bearing on contexts of societal-reportorial commentary, testimonial discourse, and historical narratives. Autofictional practice is viewed increasingly as opening up crucial space for new perspectives and alternative histories to emerge. Prior to the transformations in approaches to truth that we have discussed, “autofictional testimony” would have sounded like a contradiction in terms. In the course of our study, however, several critics explore autofictional practices in relation to or as a form of testimonial discourse.Footnote59 The multiple and complex truths that autofictional works explore are often viewed now as necessary tools in dealing with the past and, in particular, in revisiting and rewriting histories that have been dictated by the dominant powers, especially in postcolonial contexts. Recent work has highlighted the important connection between a more collaborative concept of truth and the way in which western societies confront their past, as well as how it should shape the future.Footnote60

In sum, the hybridization and boundary-pushing that is inherent in and privileged by autofictional works has taken on new importance in view of twenty-first century responses to questions of forced displacement and migration, queer and transgender identities,Footnote61 and challenges to stories told in history books, propagated in educational institutions, and portrayed in the cultural sphere (including literary works but also museums). The understanding that autofiction offers an important space within life writing for subordinate groups is a constituent part of the concept: the sociological basis of Doubrovsky’s definition, as Dix notes, was that while only “somebodies” were justified in writing an autobiography, “nobodies” like him could write autofictions (2019). While this dimension has been sidelined in more virulent debates around taxonomy, navel-gazing, and exhibitionism, its prominence in the Anglophone conversation is clear from Frank Zipfel’s Citation2005 entry in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Narrative Theory. Zipfel identifies as a focal point of critical discussions the idea that autofiction “allows for the creative reconfiguration of minority identities,”Footnote62 and this motif is evident through the wide range of contexts explored in our corpus. At the heart of the possibilities in autofictional practice for so-called minority writers is the approach to identity, selfhood, and experience as shifting, fluid, and plural, and the challenge this poses to rigid, fixed, and singular narratives.

Coda

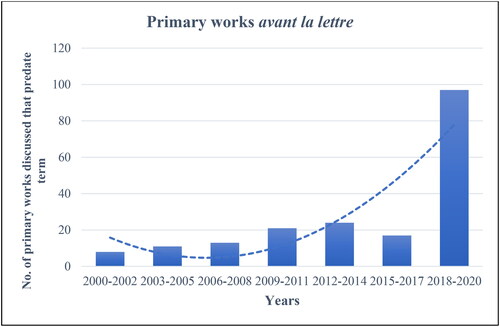

We will conclude by reflecting on a notable difference in our findings in terms of how the discussion of autofiction has expanded diachronically in comparison to its inclusion of different media, languages, cultures, and geographical contexts. While there is more discussion now of autofiction avant la lettre than there was before the new millennium, we do not see the same kind of extension diachronically that was broadly characteristic of our results for media, nation, language, and geographical region (see of the appendix). Up to 2018, the rise is considerably slower: the number of primary works increases in small increments from 8 in 2000–2 up to a peak of twenty-four in 2012–14, thanks primarily to the publication of Ioannidou’s Citation2013 doctoral thesis on Greek autofiction; the first full-length work in our results which sets out to prove the existence of autofiction before the term. There is a subsequent dip to seventeen works in 2015–17, before a striking increase to ninety-seven in 2018–20, the biggest jump across our findings. While Autofiction in English and the Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction contribute to this high number, outside these works there is a strong trend in all three years to include works avant la lettre under the umbrella of autofiction. Relative to the other key areas that we have explored in this study (language, nation, media), we see less theoretical engagement with diachronic extensions. Whereas the discussion of a different medium under the umbrella of autofiction is often accompanied by an impetus to establish its particularities, the inclusion of works which predate the term appears more often to be a by-product rather than the focus of broader applications of the term. At least in the Anglophone conversation, therefore, it is the area with most room for further theoretical development, building especially on the pioneering developments in Wagner-Egelhaaf’s Handbook with respect to how the diachronic expansion of the term affects or is affected by its global spread.Footnote63

Does the slower diachronic extension that we have described indicate that we lack an appropriate term, that the more encompassing understanding afforded by the adjective is not sufficient for thinking autofictional modes diachronically? This is unlikely, since we do see diachronic extension under the term of autofiction, and even more so when it is used adjectivally. Although ultimately, we are not able to answer why diachronic extension is still lacking, our inclination is that it has to do with the need to pay more attention to contextual, socio-historical and textual-formal specificities. We might need, in other words, to be alert to autofictional texts that look very different and that work differently, too. Perhaps we see and understand autofiction diachronically only if we consider texts in their historical and individual context of production and reception. Analogous to the question we posed at the end of the previous section, we might thus reflect on whether we need to explore the specificities not only of autofictional practice in different regions, languages, and cultures, but also of modernist, Victorian, and Romantic autofiction, for example, or of autofiction in the transcendentalist tradition, autofiction of the early-eighteenth-century pseudofactual period, Roman and ancient Greek autofiction, and so on and so forth. Our claim is not that autofictional texts and strategies are all-pervasive, but that, since they have been identified in select texts before Doubrovsky, it is worth looking more actively for further evidence of them, and reflecting on what terminological and cognitive affordances we might need to find them. By virtue of promising insights into how autofictional practice has evolved, into the different forms, and at times guises, in which it can appear, and into how it works in diverse contexts across (literary) history, such an endeavour would further enrich our understanding of autofiction as a contemporary practice and of its workings on a global scale. Increasing reflection on global autofictional practice—especially if it goes hand in hand with attention to differences in forms and functions, to specificities and distinctions in different contexts—might moreover facilitate diachronic extension. One reconceptualization, that is, one refocusing, reframing, and the ensuing cognitive reorientation, can thus afford another. We can think of this process as an affordance on yet another level or of yet another kind.

A final possible reason for the lack of diachronic extension in the critical discussion of autofiction is that we are currently more concerned with the present and future than we are with the past. From 2012 onwards, twenty-first century works make up over half of the primary sources discussed in each three-year data set. The proportion jumps significantly from 29.1% in 2009–11 to 51.3% in 2012–14, peaking at 60.5% in 2015–17 before a small decrease to 55.6% in 2018–20. There is a strong focus in the Anglophone discussion on contemporary practice, therefore, which contributes to the slower diachronic extension of the term in our study (although it will be interesting to observe whether the drop in the proportion of twenty-first century works combined with the increase in works avant la lettre in 2018–20 marks a change in direction). The draw of these twenty-first century works seems to have resulted in less critical interest in looking for autofictional texts in earlier periods, perhaps because contemporary practice appears more immediately relevant to the prominent debates around identity and testimony that we have discussed. If this is indeed contributing to the relative lack of diachronic extension, we would call for it to be remedied. In order to better understand, respond to, and live within a culture that has uprooted to some extent the categories of facts and truth, and which is becoming more conscious of the need to revisit how western societies confront their past, how we can form collective memory in view of better futures, how we must challenge universal verities, and decolonize the academic curriculum, it is vital that we probe further into how truth, memory, and individual as well as collective identity have been conceived of, pushed at, and reconceived throughout the centuries. In any case, the fact that autofictional texts are so far discussed only sparingly in diachronic perspective constitutes proof, as one of the anonymous reviewers of this essay kindly noted, that the affordances and also the limitations around the concept of autofiction are still being negotiated.

Acknowledgments

This project was made possible by funding from the Oxford-Berlin Research Partnership. We would like to thank Professor Elleke Boehmer for her guidance in the initial stages of the project and for her encouragement throughout and Anna Glieden for her diligent support with the primary research. We would also like to thank members of the Centre for Literature, Cognition and Emotions, University of Oslo, for inspiring our thinking about terminological affordances in autofiction research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alexandra Effe

Alexandra Effe is Postdoctoral Fellow within the interdisciplinary research center “Literature, Cognition and Emotions” (LCE) at the University of Oslo. She is the author of J. M. Coetzee and the Ethics of Narrative Transgression (Palgrave, 2017), as well as co-editor of The Autofictional (Palgrave, 2022) and of Autofiction, Emotions, and Humour (Routledge, 2023). She has published articles and book chapters on narrative and cognitive theory, life writing, manuscript studies, twenty-first-century literature, postcolonial literature, and testimonial writing. As Visiting Scholar at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing, she co-convened the project “Autofiction in Global Perspective.”

Hannie Lawlor

Hannie Lawlor is Lecturer in Spanish at University College Dublin. She holds a PhD from the University of Oxford and her research interests include autobiographical and autofictional practices, intergenerational transmission of trauma, fictional stagings of impossible conversations, and narrative perspective in twentieth and twenty-first-century prose in Spain and France. She is co-editor of The Autofictional: Approaches, Affordances, Forms (Palgrave, 2022) with Dr Alexandra Effe, and her thesis monograph, Relational Responses to Trauma in Twenty-First-Century French and Spanish Women’s Writing, is forthcoming with Oxford University Press (2024).

Notes

1 While the coining of autofiction is attributed most frequently to Serge Doubrovsky and his 1977 work, Fils, Myra Bloom observes that the term had in fact already appeared in Anglophone criticism five years prior, when it was used by Paul West in his review of Richard Elman’s Fredi & Shirl & The Kids (1972) in the New York Times. As Bloom writes, despite the fact that West subsequently his own self-described autofiction, Gala (1977) in the same year as Fils, it was Doubrovsky who went on to become the “patriarch of autofiction,” primarily thanks to his repeated return to and redefinition of the term in the course of his oeuvre. Bloom, “Sources of the Self(ie),” 5–6.

2 Karen Ferreira-Meyers, “Autofiction: ‘imaginaire’ and Reality,” 31. Philippe Gasparini gives a thorough overview of autofiction criticism in the 1990s and early 2000s in French in Autofiction: une aventure du langage.

3 Using the advanced search tool, we inputted the term “autofiction” and generated the results for all languages and items for each year of our search period. We discounted subsequently from these results book reviews and works in which “autofiction” appeared only in the bibliography.

4 We did not consider in this study the connections between the scholar’s country of origin and the primary works on which they focused, but we recognize that the choice of corpus is shaped significantly by this linguistic and national background. Our focus, however, was on demonstrating the global spread of the primary texts discussed in Anglophone criticism irrespective of this influence of origins.

5 Mortimer, “Autofiction as Allofiction,” 22.

6 Edwards, “Autofiction in the Dock,” 78.

7 Walker, “Conversion, Deconversion, and Reversion,” 200.

8 Womble, “Narrations of Ambiguity,” 222.

9 Dix, Autofiction in English, 2.

10 Originally used by psychologist James J. Gibson, the term affordance designates potential uses to which an object or feature can be put (a chair offers the affordance of sitting, for example, also climbing on, throwing, etc.). Terence Cave, in Thinking with Literature (2016) has drawn attention to the cognitive affordances of literature, but also of language more generally, including of specific terms.

11 Cave, Thinking with Literature, 62.

12 Cf. n. 20, emphases in original.

13 Wagner-Egelhaaf, Handbook of Autobiography/Autofiction, 21.

14 Such a work is not impossible, Lejeune suggests, but no example exists in practice (Le pacte autobiographique, 31).

15 James, “Jacques Roubaud,” 43.

16 de Bloois, “Introduction,” n.p.

17 Colonna, “L’autofiction”; Autofiction.

18 See Gasparini, Autofiction: une aventure, for further details on how the French discussion has developed.

19 de Bloois, “Introduction,” n.p.

20 “Hybrid” is by far the most common of these qualifiers, appearing in James N. Agar (Citation2007); Andrew Sobanet (Citation2008); Sanna Karkulehto (Citation2012); Maria Alhambra Díaz (2013); Jochen Mecke (Citation2015); Florence Labaune-Demeule (Citation2016); Debra G. Parker (Citation2016); Yanbing Er (Citation2018); Wagner-Egelhaaf (Citation2019); and Teresa Pepe (Citation2019), and Virginia Pignagnoli (Citation2019) uses “hybrid genre-narrative.” Frank Zipfel (Citation2005) and Sara Kippur (Citation2009) use “paradoxical” and “unstable,” respectively, and Chelsea Largent (Citation2019) describes autofiction as a (non) genre. Amalia Rechtman (Citation2005) and Caren Barnezet Parrish (Citation2006) both place genre in inverted commas.

21 Sadoux and Stuart Kendall in Citation2002; Gregory Lattanzio and Ruth Cruickshank in Citation2009; Susanna Hempstead, Emily Spiers, Elliot Evans, and Oliver Davis in Citation2015; Leigh Gilmore (Citation2016); Agerup (Citation2017); Dix, Nina Schmidt, and Joshua Rivas in Citation2018; and Kate Willman and Jeffrey Clapp in Citation2020.

22 Pamela Paine (Citation2000); Katharine Harrington and Charles Forsdick in 2006; Lia Brozgal (Citation2007); Necia Chronister, Edward Muston and Candace Caraco in Citation2011; Sally-Ann Murray (Citation2014); Shadi Neimneh (Citation2015); Karen Steigman and Benjamin Hoffman in Citation2016; Alexandra Effe (Citation2017); Anna Kemp (Citation2018); Wagner-Egelhaaf (Citation2019); Allira Hanczakowski, Kaitlin Roquel Yeomans and Alexandra Schwartz (Citation2020).

23 Fabio Ferrari (Citation2006); Lawrence Schehr, Madeline Walker, Louise Vasvári, and Thanh Cao (Citation2009); Ferreira-Meyers (Citation2012); Jennifer Cadman (Citation2013); Iván Villarmea Alvarez (Citation2014); Per Krogh Hansen, Ştefana-Teodora Popa, and Elise Hugueny-Léger (Citation2017) all describe autofiction as a sub-genre of autobiography or life writing, while Anneleen Masschelein (Citation2010); Stefan Herbrechter (Citation2012); and Fabienne Cheung (Citation2018) call it a subdivision.

24 Critics include Daniel Pope and Mildred P. Mortimer in Citation2013; Christian Lorentzen (Citation2017); Gisli Vogler (Citation2019). Alison Gibbons (Citation2018) argues that autofiction is a reading strategy as well as a literary genre.

25 Kent Minturn (Citation2007); and Anders S. Johansson (Citation2014).

26 Claire Bazin (Citation2007); David Hamilton (Citation2017); Benaouda Lebdai and Johanna Vollmeyer in Citation2018; Sam Meekings and Morna Mcdermott Mcnulty in Citation2019; and Mette Leonard Hoeeg (Citation2020).

27 See, for example, Laura Rascaroli, who characterizes Peter Whitehead’s 1977 film Fire in the Water as simultaneously an (auto)fiction, a documentary, a self-portrait, a political and cultural critique, and an avant-garde film in “Burning Passions, Flammable Decade” (657). In 2012, David C. Phillips identifies autofiction as one of two potential categories for the Francophone and Anglophone works that he discusses in “Black Blood/Red Ink,” as does Nicoletta Di Ciolla in her analysis of Italian author Roberto Saviano’s Gomorra in “Crime Fact.”

28 Rachel Douglas (Citation2011) describes autofiction as enmeshed with travel-writing and testimony in Dany Laferrière’s work, and Karkulehto (Citation2012) identifies characteristics of autofiction and confessional literature as well as autobiography in Finnish writer Pirkko Saisio’s Punainen Erokirja.

29 Steven Urquhart (Citation2011) identifies autofiction as one of the genres that Gerard Bessette mixes in Le Semestre, and Ruth Lipman (Citation2014) perceives Patrick Modiano’s Dora Bruder as containing elements of autofiction.

30 Elizabeth Jones (Citation2002); Kippur (Citation2009); Masschelein and Jan Baetens (2010); Arcana Albright (Citation2011); Shirley Jordan (Citation2013); Dawn M. Cornelio (Citation2018); and Pepe (Citation2019) refer to “autofictional projects,” while Sobanet (Citation2001); Matthew Todd Womble (Citation2015); Graham J. Matthews (in Dix, Citation2018); and Bloom (Citation2019) describe “autofictional techniques.” “Autofictional strategies” is used by Isabelle Vanderschelden (Citation2012); Hansen and Glăvan (Citation2017); Alison Gibbons, Timotheus Vermeulen, and Robin Van Den Akker (2019); and Serena Fusco (Citation2020).

31 Adrienne Angelo (2014), for example, perceives Marie Nimier’s Photo-Photo as playing with the taxonomy of autofiction and autobiography. Motte (2015) describes Jean Rolin as “flirting with autofiction” in L’Explosion de la durite, while Neimneh suggests that J. M. Coetzee’s works “partake in this genre” (“Autofiction and Fictionalisation,” 1).

32 Kunt posits autofiction as a potential label for Swiss writer Sacha Batthyány’s Und Was Hat Das Mit Mir Zu Tun? in “Mapping the Intergenerational Memory”; Agerup suggests in “Diegetic Biographism” that autofiction is one approach by scholarly critics to Annie Ernaux’s work; and Frangos lists autofiction in “The Girl Who Fell” as one of several classifications for Quatari-American artist Sophia Al-Maria’s The Girl Who Fell to Earth. In Derrida and Other Animals, Still describes autofictional elements as being present in Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Red Riding Hood’ and ‘Mrs Midas’ and observes that Cixous’s L’Amour du loup includes complex autofictional play, while Delfino considers the fictional re-writing of the author’s past in Pierfrancesco Diliberto’s La mafia uccide as bringing the film “into close proximity with the autofictional genre” (“A Cinematic Anti-Monument,” 387).

33 Gratton, “Autofiction,” 241–253.

34 Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s work Dictee, discussed by Largent in “The Absolute Self(ie),” is in English and French and includes Korean characters.

35 By “nation” in this study, we refer to the main place in which an author has lived and worked; if an author has dual nationality, we have included them under the country that is most relevant to the text in question (most frequently their country of birth).

36 Bloom, “Sources of the Self(ie),” 1–2.

37 Doubrovsky, “Ne pas assimiler autofiction,” 28. Translation is authors’ own.

38 Ioannidou, “Autofiction à la grecque,” 39.

39 Pla Fernández, “A Comparative Study,” 126.

40 Saunders, “Autofiction, Autobiografiction, Autofabrication,” 768.

41 Mortimer, “MRIs of Sollers’s fictions,” 383.

42 Dix, “Autofiction: The Forgotten Face,” 74.

43 To qualify as “reflective” in this study, the requirements were an awareness of different definitions of autofiction and an explanation as to why the author chooses to apply a particular understanding in this work, or in-depth engagement with the difference between the uses of autofiction in different cultural or linguistic contexts.

44 Indeed, in 2017, critics who had previously used the term unreflectively now use it reflectively (Marjorie Worthington [Citation2014, Citation2017] and Lorna Martens [Citation2014, Citation2017]).

45 Visible, for example, in recent larger projects, including The Autofictional: Approaches, Affordances, Forms (2022), Autofiction and Cultural Memory (2022), and Radical Realism, Autofictional Narratives and the Reinvention of the Novel (2022).

46 Dix, Autofiction in English, 120.

47 Pepe, Blogging from Egypt, 22.

48 Jordan nonetheless observes a similar shift in the Francophone discussion when she writes that the focus of the second conference in the field, held at Cerisy-la-Salle, was on how “autofictional writing has been transformed as it has been harnessed to express a wide range of cultural realities” (“Autofiction in the Feminine,” 82). See also Edwards, “Autofiction in the Dock.”

49 See Jordan, “Autofiction in the Feminine,” and Kaye Mitchell, Writing Shame, for detailed discussions of this gender-inflected accusation.

50 Moraru, Cosmodernism, 5.

51 See, for example, James, “Jacques Roubaud.”

52 See Sam Ferguson, “Diary–writing,” and Popa, “My Struggle,” for more detailed accounts of this evolving relationship.

53 See J’Lyn Chapman, “Unmasking Sanctioned Authority”; Nicholas Dames, “New Fiction of Solitude”; and Hansen, “Autofiction.”

54 French writer Catherine Cusset’s article, “The Limits of Autofiction” (2012) becomes a key point of reference in this strand of the discussion. See also Mortimer (Citation2009); David Thompson (Citation2013); Laura Di Summa Knoop (Citation2017); Michael’s chapter in Autofiction in English (2018); Rivas (Citation2018); Pignagnoli (Citation2019); Mitchell (Citation2019).

55 See Pope, “Enigmatic Realism” and Worthington, “Ghosts of Our Fathers.”

56 Kevin Corbett, “Beyond Po-Mo”; Stefan Kjerkegaard, “Getting People Right”; and Sarah Foust Vinson’s chapter in Autofiction in English.

57 See Bloom, “Sources of the Self(ie),” for a detailed discussion of the relationship between autofiction and digital platforms.

58 See, for example, Ferreira-Meyers, Citation2012; Dominik Antonik, Citation2012; Edwards, Citation2014; Kylie Cardell, Citation2017; and Inge Van De Ven, Citation2018.

59 Examples include Rosa-Àuria (2009); Munté Ramos and Douglas in Citation2011; Jordana Blejmar and Natalia Fortuny (Citation2013); Rivas (Citation2017); Melyssa Haffaf (Citation2018); and Eric Chevrette (Citation2019).

60 See, for example, Dix’s Autofiction and Cultural Memory (2022).

61 Works in our study that connect autofictional practices with the expression and navigation of queer identity include Oliver Davis and Hector Kollias (Citation2012); Ioannidou (Citation2013); Jonathan Sturgeon (Citation2014); Spires and Rivas in 2018; Largent; Jules O’Dwyer; Yasmina Jaksic (Citation2019); and Hunter V. Capps (Citation2020).

62 Zipfel, “Autofiction,” 37.

63 In The Autofictional: Approaches, Affordances, Forms (2022), we attempt to develop this area of the critical conversation. Several chapters engage with precursors of autofiction: Wagner Egelhaaf engages in depth with the relationship between Goethe’s work and the autofictional mode; Ben Grant’s investigation of the co-presence of autofiction and self-portraiture in the work of French author and photographer Claude Cahun considers a precursor to autofiction across different media; and Ricarda Menn and Melissa Schuh take a diachronic approach, tracing the evolution of literary, serial autofictional texts from Dorothy Richardson to Rachel.

Bibliography

- Agar, James N. “Self–Mourning in Paradise: Writing (about) AIDS through Death–Bed Delirium.” Paragraph 30, no. 1 (2007): 67–84.

- Agerup, Karl. “Diegetic Biographism: Authorial Intrusions and Interdiscursive Anchorages Producing a Rhetoric of Authenticity in Three Books by Annie Ernaux.” Enthymema 19 (2017): 222–234.

- Alambra Díaz, Maria. “Autobiography as a Curiosity: Generic (In)Definition, Narrative Time and Figuration in Vladimir Nabokov’s Speak, Memory, Georges Perec’s W or the Memory of Childhood and Javier Marías’s Dark Back of Time.” PhD diss., University of East Anglia, 2013.

- Albright, Arcana. “Remapping Autobiographical Space: Jean-Philippe Toussaint’s Self-Effacing Self-Portraits.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 15, no. 5 (2011): 543–551.

- Angelo, Adrienne, and Erika Fülöp. Protean Selves: First-Person Voices in Twenty-First Century French and Francophone Narratives. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

- Antonik, Dominik. “The Author as a Brand.” Teksty Drugie 6 (2012): 62–76.

- Baetens, Jan, and Douglas Basford. “Pierre Alferi’s ‘Allofiction’: A Poetics of the Controlled Skid.” SubStance 39, no. 3 (2010): 66–77.

- Barello, Simona. “At the Margin of the Margin: Female Identities within Beur Literature and Film.” PhD diss., University of New York, 2007.

- Barnezet Parrish, Carren. “The Authorial Figure in Nathalie Sarraute’s Enfance, and Assia Djebar’s L’amour, la fantasia.” PhD diss., University of California, 2006.

- Bazin, Claire. “Janet Frame: ‘Keel and Kool’ or Autobiogra/Fiction.” Commonwealth: Essays and Studies 29, no. 2 (2007): 19–28.

- Blejmar, Jordana, and Natalia Fortuny. “Introduction.” Journal of Romance Studies 13, no. 3 (2013): 1–5.

- Bloom, Myra. “Sources of the Self(ie): An Introduction to the Study of Autofiction in English.” ESC: English Studies in Canada 45, no. 1-2 (2019): 1–18.

- Brandt, Jenn. “Art Spiegelman’s in the Shadow of No Towers and the Art of Graphic Autofiction.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 5, no. 1 (2014): 70–78.

- Brozgal, Lia. “Reading Albert Memmi: Authorship, Identity and the Francophone Postcolonial Text.” PhD diss., University of Havard, 2007.

- Cadman, Jennifer. “The Displaced I: A Poetics of Exile in Spanish Autobiographical Writing by Women.” PhD diss., University of St Andrews, 2013.

- Cao, Thanh. “Identity Presentation in Stories of Past and Present: An Analysis of Memoirs by Authors of the 1.5 Generation of Vietnamese Americans.” PhD diss., University of Kansas, 2009.

- Capps, Hunter V. “Contracting Subjectivities: Que(e)rying Gesture, Affect, and Politics in French and American AIDS Literature.” PhD diss., University at Buffalo, 2020.

- Caraco, Candace. “Artifaction: The Scene of Memory in Postmodernity.” PhD diss., University of Virginia, 2011.

- Cardell, Kylie. “The Future of Autobiography Studies: The Diary.” A/b: Auto/Biography Studies 32, no. 2 (2017): 347–350.

- Cave, Terence. Thinking with Literature: Towards a Cognitive Criticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Chapman, J’Lyn. “Unmasking Sanctioned Authority: A Study of Word and Image in the Novels of W. G. Sebald.” PhD diss., University of Denver, 2008.

- Cheung, Fabienne. “Identity in Play: Leiris, Perec, and Bénabou.” PhD diss., University of Manchester, 2018.

- Chevrette, Eric. “From Self-Fictionalization to Self-(Dis)Engagement: Autofiction in Frédéric Beigbeder’s Windows on the World.” ESC: English Studies in Canada 45, no. 1-2 (2019): 61–83.

- Chronister, Necia. “Topographies of Sexuality: Space, Movement, and Gender in German Literature and Film since 1989.” PhD diss., University of Washington, 2011.

- Clapp, Jeffrey. “Undisguised Alter Ego: Mary McCarthy’s Autofictional Career.” Life Writing 17, no. 1 (2020): 27–43.

- Colonna, Vincent. Autofiction & autres mythomanies littéraires. Auch: Tristam, 2004.

- Colonna, Vincent. “L’autofiction, essai sur la fictionalisation de soi en littérature.” PhD diss., École des hautes études en sciences sociales, 1989.

- Corbett, Kevin J. “Beyond Po-Mo: The “Auto-Fiction” Documentary.” Journal of Popular Film and Television 44, no. 1 (2016): 51–59.

- Cornelio, Dawn. “Activism and Autofiction: Chloé Delaume’s Response to the Patrick Le Lay Affair.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 22, no. 1 (2018): 15–22.

- Cruickshank, Ruth. Fin de millénaire French Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Cusset, Catherine. “The Limits of Autofiction.” Conference presentation, 2012. http://www.catherinecusset.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/THE-LIMITS-OF-AUTOFICTION.pdf

- Dames, Nicholas. “The New Fiction of Solitude.” The Atlantic Monthly 317, no. 3 (2016): 92–101.

- Davis, Oliver. “Leading by Example: A Queer Critique of Personalization and Coercive Community Governance in Act up-Paris’s Operation against the Bareback Writers.” Sexualities 18, no. 1-2 (2015): 141–157.

- Davis, Oliver, and Hector Kollias. “Editors’ Introduction.” Paragraph 35, no. 2 (2012): 139–143.

- de Bloois, Joost. “Introduction: The Artists Formerly Known as… or, the Loose End of Conceptual Art and the Possibilities of ‘Visual Autofiction’.” Image & Narrative 8, no. 19 (2007).

- Delfino, Massimiliano L. “A Cinematic Anti-Monument against Mafia Violence: P. Diliberto’s La mafia uccide solo d’estate.” Annali d’italianistica 35 (2017): 385–401.

- Di Ciolla, Nicoletta. “Crime Fact versus Crime Fiction: Alternative Strategies for the Mobilization of the ‘Ethic Minority’ in Twenty-First-Century Italy.” Italian Studies 67, no. 3 (2012): 411–424.

- Di Summa Knoop, Laura. “Critical Autobiography: A New Genre?” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 9, no. 1 (2017).

- Dix, Hywel, ed. Autofiction in English. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Dix, Hywel. Autofiction and Cultural Memory. London: Routledge, 2022.

- Dix, Hywel. “Autofiction: The Forgotten Face of French Theory.” Word and Text 7, no. 1 (2017): 69–85.

- Doloughan, Fiona. Radical Realism, Autofictional Narratives and the Reinvention of the Novel. London: Anthem Press, 2022.

- Donnarumma, Raffaele. “Constructing the Hypermodern Subject: Troppi Paradisi by Walter Siti.” The Italianist 35, no. 3 (2015): 440–452.

- Doubrovsky, Serge. “Autobiographie/Vérité/Psychanalyse.” L’Esprit Créateur 20, no. 3 (1980): 87–97.

- Doubrovsky, Serge. “Ne pas assimiler autofiction et autofabulation.” Magazine littéraire 440 (2005): 28.

- Douglas, Rachel. “Rewriting America/Dany Laferrière’s Rewriting.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 15, no. 1 (2011): 67–78.

- Edwards, Natalie. “Autofiction in the Dock: The Case of Christine Angot.” In Protean Selves: First–Person Voices in Twenty-First-Century French and Francophone Narratives, edited by Adrienne Angelo and Erika Fülöp, 68–81. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2014.

- Effe, Alexandra. “Coetzee’s Summertime as a Metaleptic Conversation.” Journal of Narrative Theory 47, no. 2 (2017): 252–275.

- Effe, Alexandra, and Hannie Lawlor, eds. The Autofictional: Approaches, Affordances, Forms. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2022.

- Er, Yanbing. “Contemporary Women’s Autofiction as Critique of Postfeminist Discourse.” Australian Feminist Studies 33, no. 97 (2018): 316–330.

- Evans, Elliot. “Your HIV-Positive Sperm, My Trans-Dyke Uterus: Anti/Futurity and the Politics of Bareback Sex between Guillaume Dustan and Beatriz Preciado.” Sexualities 18, no. 1-2 (2015): 127–140.

- Ferguson, Sam. “Diary–Writing and the Return of Gide in Barthes’s ‘Vita Nova.” Textual Practice 30, no. 2 (2016): 241–266.

- Ferrari, Fabio. “Italian Myths and Counter–Myths of America: Allegorical Representations of America in 20th–Century Italian Literature and Film.” PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2006.

- Ferreira-Meyers, Karen. “Autofiction: ‘Imaginaire’ and Reality: An Interesting Mix Leading to the Illusion of a Genre?.” Caietele Echinox 23 (2012): 103–116.

- Forsdick, Charles. “‘(In)connaissance de l’Asie’: Barthes and Bouvier, China and Japan.” Modern & Contemporary France 14, no. 1 (2006): 63–77.

- Frangos, Mike. “The Girl Who Fell to Earth: Sophia Al–Maria’s Retro–Futurism.” C21 Literature: Journal of 21st-Century Writings 5, no. 3 (2017).

- Fraser, Morven. “Genres Instables: Ludic Performances of Autofiction in the Works of Catherine Cusset, Philippe Vilain, Chloé Delaume and Éric Chevillard.” PhD diss., University of St Andrews, 2015.

- Fusco, Serena. ““Each of Them Thin and Barely Opaque”: Ruth Ozeki’s Truth Approximations.” Between 9, no. 18 (2020).

- Gasparini, Philippe. Autofiction: une aventure du langage. Paris: Seuil, 2008.

- Gibbons, Alison. “Autonarration, I, and Odd Address in Ben Lerner’s Autofictional Novel 10:04.” In Pronouns in Literature: Positions and Perspectives in Language, edited by Alison Gibbons and Andrea Macrae, 75–86. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Gibbons, Alison, Timotheus Vermeulen, and Robin Van Den Akker. “Reality Beckons: Metamodernist Depthiness beyond Panfictionality.” European Journal of English Studies 23, no. 2 (2019): 172–189.

- Gilmore, Leigh. “Conclusion: Joan Didion’s Style.” A/b: Auto/Biography Studies 31, no. 3 (2016): 614–617.

- Glăvan, Gabriela. “Revisiting the Eastern European Provinces.” Orbis Litterarum 72, no. 5 (2017): 384–410.

- Gratton, Johnnie. “Autofiction.” In Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms, edited by Margaretta Jolly, Vol. 2, 241–253. London: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001.

- Haffaf, Melyssa. “Shifting Masculinities from North Africa: In Yasmina Khadra, Tahar Ben Jelloun, Mohamed Leftah and Abdellah Taïa’s Fictions.” PhD diss., University of Miami, 2018.

- Hamilton, David. “A Certain Arc.” Fourth Genre: Explorations in Nonfiction 19, no. 2 (2017): 129–138.

- Hanczakowski, Allira. “Uncovering the Unwritten: A Paratextual Analysis of Autofiction.” Life Writing 19, no. 1 (2020): 127–144.

- Harrington, Katharine. “Writing between Borders: Nomadism and Its Implications for Contemporary French and Francophone Literature.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 10, no. 2 (2006): 117–125.

- Hempstead, Susanna. “‘I Am Made and Remade Continually’: The Broken Subject and Autofiction in Nella Larsen and Virginia Woolf.” MA diss., State University of New York, 2015.