ABSTRACT

Both the models of moral distress and of moral injury place an emphasis on various types of moral challenges that may violate the individual’s conscience, evoking moral emotions. Yet, there appears to be great conceptual confusion as regards both scholarly perspectives. The purpose of this article is to further elaborate on the qualitative content and conceptual demarcations of the theories of moral injury and moral distress. In the light of this theoretical elaboration, we propose an integrated moral distress and injury scale that provides a more holistic overview of these moral challenges. We suggest that the utility and applicability of the moral injury and moral distress theories may benefit from the integration of these concepts. A practical implication of our theoretical understanding is that processes of recovery, which involve moral dimensions, are complex. In line with this understanding, we advocate a holistic approach to health and well-being among military service members and Veterans.

What is the public significance of this article? — As moral challenges exhibit a large number of different characteristics, the authors advocate a synthesis of moral distress and injury theories to capture the breadth and depth of moral stressors in both time and space of military duty. A conceptual development of an integrated moral distress and injury scale advances the understanding of moral challenges and health-related outcomes in a military context. The authors believe that understanding the complexities of health and well-being may benefit from the integration of these concepts.

Introduction

The complexity of military operations has led to new ethical challenges for the military (Richardson, Verweij, & Winslow, Citation2004). For example, there has been a shift in societal values and expectations concurrent with technological advances, and, in parallel with the development of a more chaotic and geopolitically complex security context (Lagacé-Roy, Citation2007). The common citizen finds it more difficult to accept war-related deaths, particularly in “unpopular wars” and often demonstrates greater knowledge and a higher degree of concern as regards the righteous treatment of an adversary. In addition, military activities often involve “operations-other-than-war” that affect third parties to an increasing extent. The difference between combatants and noncombatants has also become increasingly more difficult to discern which is compounded by the fact that adversaries tend to resort to unconventional methods, with little consideration for the laws of war (Bowyer, Citation2009). Drawing on the fields in philosophy and the social sciences, future military activities will demand greater moral sensitivity and ability (Richardson et al., Citation2004) as military personnel are expected to do the right thing, time and again under intense pressure.

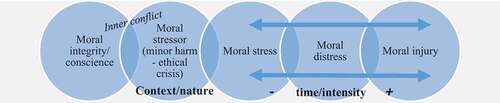

Figure 1. The integrated moral distress and injury scale (including context/nature and time/intensity dimensions of moral stressors and their health-related outcomes)

Service members’ experiences of moral aspects of military life have recently gained attention in the light of the complexities of military operations combined with adversities in the aftermath of military service (see for example, Fourie, Citation2015; Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016; Jinkerson, Citation2016). In particular, there has been a growing emphasis on morally challenging situations and their potential psychological and spiritual consequences for the individual self-integrity of military personnel or Veterans (see for example, Grimell, Citation2016a, Citation2017; Hyllengren et al., Citation2016; Nilsson, Brandow, Ohlsson, & Larsson, Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2015; Nilsson, Sjöberg, Kallenberg, & Larsson, Citation2011; Waaler, Larsson, & Nilsson, Citation2019; Waaler, Nilsson, Larsson, & Espevik, Citation2013). Previous research shows how moral emotions such as guilt, remorse and shame may arise when an individual perceives a discrepancy (cognitive dissonance) between their “own actual behavior (or unjustified lack of activity) and the wish to conform to his or her own desired self-image and values” (Breslavs, Citation2013, p. 66). Miller (Citation2014) suggests that perhaps the most troubling types of moral challenges involve disagreements about moral conviction, conflicting interests, and the tension between one’s own conscience and desires.

Today, there is a growing recognition that organizational demands force individuals to struggle between resolving the principles of their own conscience/faith and their designated military responsibilities. It has been suggested that moral emotions signal a gap between social behaviors on the one hand, and values on the other, which can be of adaptive value. However, often the options available to officers and soldiers have proven relatively few and the individual is not always in a position where he or she can choose, but rather has to make decisions that violate their own morals and standards. Previous research has repeatedly shown that moral tradeoffs can be costly for the human soul (Brémault-Phillips et al., Citation2017; Brock & Lettini, Citation2012; Drescher & Foy, Citation2008; Graham, Citation2017; Grimell, Citation2018b; Moon, Citation2019; Tick, Citation2005; Vargas, Hanson, Kraus, Drescher, & Foy, Citation2013).

The authors of this article suggest that a clarification of the dimensions and the scope of moral challenges related to a military context are warranted in order to gain a holistic understanding of its nature and its potential psychological and spiritual health-related implications. There have been scholarly attempts to understand moral challenges and their potential psychological implications (see for example, Maguen & Litz, Citation2012, Citation2018; Maguen et al., Citation2011) and their spiritual consequences (Breuninger et al., Citation2019; Doehring & Ramsay, Citation2019; Grimell, Citation2016b, Citation2019a; Koenig et al., Citation2017; Kopacz & Connery, Citation2015; Vieten et al., Citation2016; Wortmann et al., Citation2017) through the constructs of moral distress and moral injury. Despite these efforts, existing models are accused of being characterized by conceptual vagueness and lack of clarity, having limitations, or being too context-specific. The moral injury model(s) perhaps is the most widely used and recognized construct when it comes to the military. By contrast, moral distress is associated empirically and theoretically with nursing ethics.

The theoretical constructs of moral distress and moral injury share some common dimensions, but differ in other respects, this means that challenges of a moral character are bound to vary depending on the perspective taken. We suggest that both theoretical constructs possess certain strengths and limitations and that, consequently, there may be advantages to integrating both perspectives to capture the breadth and depth of moral challenges, in terms of both time and space of military duty. To date, to the best of our knowledge, no study explicitly relates these theoretical constructs to each other. Thus, the purpose of this article is to explicate the need for an advanced perspective of moral challenges that may be offered by integrating the moral distress and moral injury theories.

Conceptualization of moral distress

One research field, in which moral challenges and their potential effects on the individual are investigated, studies about health-care practitioners’ experiences of so-called moral distress. In 1984, Jameton (Citation1984) suggested that moral distress may occur … “when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action” (Jameton, Citation1984, p. 6). This early definition of moral distress did not embrace moral conflict, nor moral dilemma and had a relatively narrow focus on the effects of moral constraints on an individual’s moral agency.

Wilkinson (Citation1987) developed the construct by explicating certain types of situations, which give rise to moral distress and concluded that in addition to external constraints, constraints may also be of an internal nature. Examples of this include, an individual having been socialized to follow orders or experiencing fear of losing their job, self-doubt and lack of courage (p. 21). Thus, it has been suggested that moral distress may not only result because of what an individual fails to do, but also because of what he or she actually does (read: the wrong thing).

Fourie (Citation2015) was critical of the earlier emphasis on “moral constraint” due to the risk of neglecting other forms of moral distress and has suggested a revision to expand the definition of moral distress to include the scope of conflict. Other scholars make a further distinction between “moral distress” and “moral stress.” Cribb (Citation2011), for example, criticize the moral distress concept for being applicable only with regard to acute ethical crises. This, consequently, does not include the many relatively minor harms or wrongs that originate from the legitimate demands of an occupational role and which define what is expected from the individual in such roles. The implications that can be drawn from this are that morally challenging situations inevitably “come with the job” and that tensions between an individual’s personal moral integrity and their occupational role are in fact likely to occur.

Other scholars prefer the moral stress concept instead of moral distress as it allows for the possibility of positive impacts following morally challenging situations (Lutzén & Kvist, Citation2012). It has been shown, however, that moral stress largely has negative impacts on individuals’ psychological and emotional health (see for example, Corley, Minick, Elswick, & Jacobs, Citation2005). An extensive literature review indicates that there are a variety of different reactions, ranging from rage (anger, frustration, resentment) to feelings of anxiety and sadness (e.g., embarrassment, shame, guilt, dread, anxiety, grief and depression) in addition to feelings related to lack of power such as a sense of helplessness, powerlessness, self-blame and loss of self-worth (McCarthy & Gastmans, Citation2015). The literature also provides an account of what is referred to as moral stress reactions identified in situations containing a moral dimension, including experiences of insufficiency, powerlessness, meaninglessness and frustration (Larsson, Nilsson, & Waaler, Citation2018). The individual has not been able to live up to his or her moral standards, which is experienced as painful. In the literature, such reactions have been labeled “ambiguous negative states” (Lazarus, Citation1991). They contain an emotional element that has its physiological basis in the brain's limbic system. In comparison to pure emotions as, for example, joy, fear and wrath, they additionally contain an element that reflects judgment and reasoning, based in the brains posterior parietal cortex (Greene, Sommerville, Nyström, Darley, & Cohen, Citation2001; McLure, Botvinick, Young, Greene, & Cohen, Citation2007). Based on this, it is speculated that the initial moral stress is a specific case of the more general acute stress reaction (Larsson et al., Citation2018). There is also a constant form of moral distress due to continually having to negotiate between the normative expectations of an organization and one’s own morals and standards. Thus, there is a risk that stress is accumulated over time (Richardson et al., Citation2004).

Related to moral distress is the label “second victim,” which Wahlberg (Citation2018) proposed in her study on emotional guilt, shame, and vulnerability among Swedish obstetricians and midwives as a consequence of assisting in/witnessing traumatic childbirth including severe and possibly fatal injuries. Second victim is understood with reference to the first victim in this case the mother and/or child, the primary victims of the trauma. The emotional composite of guilt, shame and vulnerability is associated with increased risk of partial or probable PTSD (posttraumatic stress disorder) among obstetricians and midwives. Wahlberg emphasizes that there can be no quick fixes to lessen the severity of traumatic events have on health-care professionals’ lives which can result in burnout. Burnout tends to be employed as a term to describe a type of disorder that occurs as a result of a process that has gone untreated for an extended period of time. Wahlberg (Citation2018) suggests that the complexity must be acknowledged in recovery processes after traumatic events.

Conceptualization of moral injury

Similar to research on moral distress, studies on moral injury focus to some extent on morally challenging situations and the potential effects on individuals of having such experiences. In 1998, Shay and Munroe presented a definition of moral injury that included three components, based upon Veterans’ narratives of injustice as a consequence of leadership malpractice, structured into the following layers: (a) through betrayal of what was considered morally right in the local culture, (b) by someone who had been legitimately granted authority within the social system, and (c) in a high-stakes situation(s). This definition emphasizes authorized, but poor command and the implications thereof for the individual service member. This approach to moral injury was further elaborated in Shay’s books Achilles in Vietnam (Shay, Citation1994/2003) and Odysseus in America (Citation2002). Shay suggested that there were deep layers of war wisdom in the Iliad and the Odyssey that provided numerous helpful insights into the consequences of war upon the combat Veterans, with whom he worked in therapeutic contexts. Authorial betrayal of what is considered morally right by a local warrior culture can cause a moral injury, which in turn may dissolve the moral code and replace it with wrath or indignant rage (Shay, Citation2002, Citation1994/2003). This may prove especially true if a closely related battle buddy would be killed by the enemy due to a decision made by a commander which is considered as a betrayal of the warrior codes. The relational bond between battle buddies may be extremely strong and deep. A betrayal of a code that results in such a loss may release the wrath of a morally and emotionally injured warrior. Shameless behavior is likely to follow in this scenario in which abuse after abuse is committed. Examples of this include, dishonoring the enemy and brutal killing (berserk state). An additional effect of betrayal is that social trust is devastated. Shay (Citation2002, Citation1994/2003) suggests that this complexity is illustrated in a complex version of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The definition of moral injury was further elaborated by Litz et al. (Citation2009) as morally injurious experiences or transgressive acts such as, “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations” (p. 700). From such a perspective, moral injury refers to a particular type of trauma, characterized by guilt, existential crisis and loss of trust (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016, p. 319). It is assumed that the individual is not able to contextualize or justify personal actions or the actions of others and as a result is not able to accommodate such experiences into preexisting moral schemas. Later definitions have come to define moral injury as a moral distress, emphasizing more long-term psychological and spiritual consequences. For example, Drescher et al. (Citation2011) suggest that moral injury is a “disruption in an individual’s confidence and expectations about one’s own or others’ motivation or capacity to behave in a just and ethical manner” (p. 9). Similarly, Silver (Citation2011) speaks of, “a deep soul wound that pierces a person’s identity, sense of morality and relationship to society” (para. 6). Nash et al. (Citation2013) demonstrate five types of situations that have shown to result in moral injury: 1) being a perpetrator (violence or outrage that goes against one’s own morals), 2) an inability to prevent death or human suffering/injury, 3) to have witnessed death and injury, 4) the loss of close ones, and 5) being in an “evil” environment. Frankfurt and Frazier (Citation2016) note that transgressive acts may exist both within (e.g., killing an enemy combatant) and outside (e.g., committing atrocities) the rules of engagement.

Attempts to develop models

Both the models of moral distress and of moral injury place an emphasis on various types of moral challenges that may violate the individual’s conscience as well as evoking moral emotions. Yet, there appears to be great conceptual confusion with regard to both scholarly perspectives. Challenges of a moral character are referred to in many different ways, including; moral (battlefield/healthcare) dilemmas, moral conflicts, transgressive acts, moral constraints and morally injurious events. The two constructs are developed within different contexts, making them relatively narrow in terms of their spatial dimensions, and which risks disregarding the complexity of moral challenges within various contexts. Although both theories emphasize acute ethical crises, the dimension of time is treated differently in each. The moral distress construct tends to emphasize more short-term acute ethical crises whereas moral injury tends to focus on more long-term effects and is often characterized as a syndrome.

There are, however, recent studies that link the terms inherent in both theories by defining moral injury as a long-term symptom of moral distress or by making moral frustration and moral distress preliminary stages to moral injury (Drescher et al., Citation2011; Yeterian, Berke, Rosenthal, & Litz, Citationin press). In the latter case, scholars make the assumption that the occurrence of such an extreme degree of mental, behavioral, social and spiritual harm and impairment is in fact, very low. This model is particularly interesting as it introduces “moral stressors” in terms of their expected severity on an outcome continuum of the degree of mental, behavioral, social and spiritual harm and impairment. They suggest that moral stressors include: 1. potential moral challenges, 2. potential moral stressors, and ultimately, 3. potential moral injuries. The authors go on to describe moral challenges as mildest in nature evoking moral frustration, moral stressors as a little more severe, giving rise to moral distress and moral injuries which are described as the most extreme form and which result in moral injury.

Even though this elaboration is intuitively appealing, we find the conceptual use questionable for several reasons. Firstly, using “moral stressors” as an umbrella concept appears confusing as “potential moral stressors” are later defined as a sub-concept with a tendency to evoke moral distress. Furthermore, by definition, moral challenges may do more than produce moral frustration. Moral emotions have a survival value as they make the individual aware that moral values may be at stake. Thus, they sharpen the senses and affect human behavior. Reactions to moral challenges may thus also be of a positive nature. The same reasoning may be applied with regard to Yeterian et al., Citationin press who propose that a moral stressor will result (only) in moral distress. According to classical stress theory, a stressor refers to a strain that evokes physical and psychological reactions, or simply put – “stress.” Consequently, stressors may in fact evoke moral emotions of various degrees and therefore, lead to both milder and more severe reactions. Lastly, it appears conceptually confusing to argue that potential moral injuries will result in moral injury. Frankfurt and Frazier (Citation2016) have previously noted the problem that comes with referring to morally injurious experiences in terms of “moral injury” as this tends to confuse the act and the outcome.

Looking more closely at scales developed to measure the occurrence of moral distress, scholars tend to use the burnout syndrome as the concept to approach more long-term consequences (see for example, Severinsson, Citation2008; Whittaker, Gillum, & Kelly, Citation2018). The same pattern can be discerned in studies about moral injury. Their starting point is in the traditional stress concept (see for example Ford, Citation2019). As regards measurements of moral injury, scales are accused of confusing exposure to transgressive acts with the effects of exposure (Frankfurt & Frazier, Citation2016). Yet, the concept of “morally injurious events” is sometimes used as a way to distinguish them from their psychological and spiritual effects, namely moral injury (see for example, Nash et al., Citation2013).

To conclude this section, there is a haphazard approach to conceptual use and diversity in the way that various concepts are theoretically addressed. We propose that an integration of the scholarly perspectives of moral distress and moral injury would provide a clearer and more complete picture of moral challenges and their potential health-related effects.

Synthesizing two theoretical constructs to advance the understanding of moral stressors

We suggest that the conceptual discussions in the previous sections have theoretical implications for the way moral challenges are approached within existing theoretical constructs. We believe that both the theory of moral distress and moral injury have limitations in that they separately fail to embrace the broad spectra of the spatial dimensions of moral challenges (for example, private/family life, home unit, deployment, combat and transition to civilian life) as well as the complexity of health-related outcomes (positive and negative, both short- and long-term) identified.

A first implication is that, because moral challenges are variable in nature, and thus not fully encompassed in the words “moral constraint, conflict, violation, omission, transgression, morally injurious events,” the term moral stressor may be a more suitable designation for this concept. This is because it is neutral and does not limit the scope to any specific type of challenge, which is similar to conclusions drawn in Yeterian et al. (Citationin press).

Secondly, health-related outcomes have both a positive and negative component that are both short- and long-term in nature and thus must be treated as such. To only emphasize here-and-now acute reactions, moral distress, or an internalized syndrome, moral injury, provides an overly simplistic models.

We argue that the breadth and depth of the nature of moral challenges amongst service members and Veterans require both the perspective of moral distress and moral injury to be more complete. Thus in , we propose a conceptual elaboration and refinement in the integrated moral distress and injury scale, which integrates the different aspects or perspectives on moral stressors and their health-related outcomes. The overlaps are significant because they indicate and demonstrate the individual variation between service members and Veterans as moral issues, challenges and especially injury have proven to be dimensional problems (Maguen & Litz, Citation2012, Citation2018).

The breadth of spatial dimensions and the nature (minor harm vs. acute crisis) in relation to the range of intensity of health-related outcomes (short-term moral stress or distress and more long-term moral injury) provides a holistic approach to moral stressors, and thus provides a nuanced understanding of their dimensional aspects. The integrated moral distress and injury scale is an illustration of how an individual with moral integrity/conscience experiences a moral stressor as a consequence of an inner moral conflict that in turn may give rise to a range of various moral emotions/reactions.

Moral emotions/reactions tend to intensify over time when an inner conflict has not been addressed or resolved. It should be noted that the inner conflict may thus be restricted in time or subject to a more cumulative process where health-related outcomes are aggravated and deepen, leading to more intense psychological and spiritual health-related outcomes. Based on this, the model implies that the further to the right a personal process of moral challenges develops, the harder the process to readjust may be. It should be noted of course that there are individual variations as there is no particular threshold that needs to be passed in order for moral injury to develop. Moral challenges are a natural part of life. Responses to and rumination upon such issues may thus be diverse and subjective depending on a combination of personal, social, cultural and societal factors.

Furthermore, experiencing moral challenges in a cumulative manner may complicate matters further. An example is given as follows to illustrate this point. Before deployment, family-related moral challenges may be particularly salient during pre-deployment training. Yet, because the service member is still at home, conflicting issues may be manageable. While on deployment, moral challenges related to these issues may escalate but also a whole new set of deployment moral types may emerge. This may further accelerate moral distress and conflicts. However because they are trained and expected to do so, the service member focuses on getting the job done. Once s/he has concluded the deployment and returns home, a potentially fragile reorientation phase begins where moral distress and conflicts need to be dealt with and resolved simultaneously. At the same time, the service member may have to leave their potentially military-radicalized deployment-identity behind and reactivate and return to a more everyday interpersonal identity as a partner and/or parent, for example. This may prove to be easier said than done.

In fact, research suggests that the home-coming and reorientation phase may be both challenging and taxing (Beder, Citation2012; Gordon, Burnell, & Wilson, Citation2020; Jolly, Citation1996; Lifton, Citation1992; Moore, Citation2012; Shay, Citation2002). In addition to family-related moral distress from a spatial perspective which can generate guilt/shame prior to or during deployment, moral rumination about decisions and/or situations on deployment which felt wrong for the individual may accelerate over time. The mixture of moral challenges topics may prove to be complex and growing. In the long term, if moral issues cannot be resolved, the individual may move further to the right on the integrated moral distress and injury scale and develop signs of a moral injury. Once this has occurred the return to some kind of “normal” and manageable post-deployment life may need a longer and guided recovery phase.

Discussion

The main contribution of this article is the conceptual development of an integrated moral distress and injury scale that serves as a basis for an advanced contextual understanding of moral challenges and health-related outcomes in a military context. As moral challenges exhibit a large number of different characteristics, we suggest that neither theory is sufficient to capture the breadth and depth of moral stressors in both time and space of military duty. Furthermore, moral challenges are variable in nature and not fully encompassed in “moral constraint, conflict, violation, omission, transgression, morally injurious events” or even “moral challenge” itself. We propose that “moral stressor” is a more suitable concept because it is neutral and does not limit the scope to any particular type of moral challenge.

This article also contributes to a more holistic approach to health-related outcomes as a consequence of having experienced moral stressors. Studies based on the moral distress theory tend to emphasize more short-term reactions whereas research results taking their theoretical staring points in the moral injury concept provide an account of rumination after morally challenging situations affecting internal substructures within a person resulting in negative long-term health implications. As general health status changes slowly and is influenced by a range of variables, including genetic disposition, normal aging, and environmental agents, which have little or no relationship to, for example, stress, these points to the importance of including assessments of more short-term reactions rather than only focusing on more severe reactions, such as moral injury. From a recovery and treatment perspective, it must be fruitful to identify early symptoms before they develop into a syndrome (Folkman, Citation1985).

In line with our wider contextual approach to moral challenges, we advocate a holistic approach to health and well-being to prevent and recover from moral issues and suggest that the development of interdisciplinary health-care teams may be a potential path for those Armed Forces, which have more traditional competency design structures in their health-care systems. This suggests that a holistic approach – a biopsychosocial–spiritual (BS) model (Berg, Citation2011; Grimell, Citation2019b; Koenig et al., Citation2017; Smith-MacDonald, Morin, & Brémault-Phillips, Citation2018; Tick, Citation2005; Wortmann et al., Citation2017) may prove more appropriate as it encompasses all of the factors associated with human complexity.

Limitations

This study has limitations. The presented synthesis of two theoretical constructs is an attempt to advance a broader model in order to better understand moral stressors within a military context. This conceptualization must be further evaluated but illustrates, in our opinion, a promising theoretical development.

In addition, we also find it necessary to call attention to our omission of the individual’s coping strategies in terms of individual resources, which are important in understanding the development of health-related outcomes. Such perspectives are central in understanding moral stressors and their health-related outcomes and must be further acknowledged and assessed with regard to moral stressors.

Even though we suggest the need for a more holistic approach to moral stressors within a Swedish military context, we do not rule out the use of the moral distress and moral injury theories separately when warranted. However, it is advisable to consider the limitations such approaches entail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Beder, J. (Ed.). (2012). Advances in social work practice with the military. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Berg, G. (2011). The relationship between spiritual distress, PTSD and depression in Vietnam combat veterans. Journal of Pastoral Care and Counseling, 65(1), 6, 1–11. doi:10.1177/154230501106500106

- Bowyer, D. (2009). The moral dimension of asymmetrical warfare: Accountability, culpability, and military effectiveness. In T. A. van Baarda & D. E. M. Verweij (Eds.), The moral dimension of asymmetrical warfare: Counter-terrorism, democratic values and military ethics (pp. 137–167). Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

- Brémault-Phillips, S., Koenig, H. G., Pargament, K. I., Plante, T. G., Chirovsky, A., Olson, J., & Weis, J. (2017, September 25–27). Spiritual dimensions of wellbeing, health and moral injury. Paper presented at the Forum of the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research (CIMVHR), Toronto.

- Breslavs, G. M. (2013). Moral emotions, conscience and cognitive dissonance. Psychology in Russia: State of the Art, 6(4), 66–72. doi:10.11621/pir.2013.0405

- Breuninger, M. W., Wilt, J. A., Bautista, C. L., Pargament, K. I., Exline, J. J., Fletcher, T. L., … Teng, E. J. (2019). The invisible battle: A descriptive study of religious/spiritual struggles in Veterans. Military Psychology, 31(6), 433–449. doi:10.1080/08995605.2019.1654306

- Brock, R. N., & Lettini, G. (2012). Soul repair: Recovering from moral injury after war. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Corley, M. C., Minick, P., Elswick, R. K., & Jacobs, M. (2005). Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nursing Ethics, 12(4), 381–390. doi:10.1191/0969733005ne809oa

- Cribb, A. (2011). Integrity at work: Managing routine moral stress in professional roles. Nursing Philosophy, 12(2), 119–127. doi:10.1111/j.1466-769X.2011.00484.x

- Doehring, C., & Ramsay, N. J. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on military moral injury. Pastoral Psychology, 68(1), 1–2. doi:10.1007/s11089-018-0859-4

- Drescher, K. D., & Foy, D. W. (2008). When they come home: Posttraumatic stress, moral injury, and spiritual consequences for veterans. Reflective Practice: Formation and Supervision in Ministry, 28, 85–102.

- Drescher, K. D., Foy, D. W., Kelly, C., Leshner, A., Schutz, K., & Litz, B. (2011). An exploration of the viability and usefulness of the construct of moral injury in war veterans. Traumatology, 17(1), 8–13. doi:10.1177/1534765610395615

- Folkman, S. (1985, August). The relationship between coping and health: Where should we look? Paper presented at Meetings of the American Psychological Association, Los Angeles.

- Ford, E. W. (2019). Stress, burnout and moral injury. The state of the healthcare workforce. Journal of Healthcare Workforce, 64, 125–127. doi:10.1097/JHM-D-19-00058

- Fourie, C. (2015). Moral distress and moral conflict in clinical ethics. Bioethics, 29(2), 91–97. doi:10.1111/bioe.12064

- Frankfurt, S., & Frazier, P. (2016). A review of research on moral injury in combat veterans. Military Psychology, 28(5), 318–330. doi:10.1037/mil0000132

- Gordon, K., Burnell, K., & Wilson, C. (2020). Outside the military “bubble”: Life after service for UK ex-armed forces personnel. Frontiers in Public Health, 8(50), 1–15. PMCID: PMC7062665. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.00050

- Graham, L. K. (2017). Moral injury: Restoring wounded souls. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press.

- Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nyström, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An FRMI of emotional engagement in moral judgement. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108. doi:10.1126/science.1062872

- Grimell, J. (2016a). Existential spiritual life among Swedish service members in transition: Marking out trends. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(3), 208–219. doi:10.1037/scp0000103

- Grimell, J. (2016b). The story of the self in the aftermath of crisis: A case study. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 29(1), 66–79. doi:10.1080/10720537.2015.1079509

- Grimell, J. (2017). Reflections on spiritual themes in a narrative psychological investigation of a secular Swede: Practical theology’s potential contributions. Practical Theology, 10(1), 88–100. doi:10.1080/1756073X.2016.1250568

- Grimell, J. (2018b). Advancing an understanding of selves in transition: I-positions as an analytical tool. Culture & Psychology, 24(2), 190–211. doi:10.1177/1354067X17707451

- Grimell, J. (2019a). Suffering for others while making others suffer: Military narratives of sacrifice. Pastoral Care & Counseling, 73(1), 30–40. doi:10.1177/2F1542305019828658

- Grimell, J. (2019b). Leaving military service with a military body: Insights for pastoral care and counseling. Pastoral Care & Counseling, 73(2), 106–114. doi:10.1177/1542305019848436

- Hyllengren, P., Nilsson, S., Ohlsson, A., Kallenberg, K., Waaler, G., & Larsson, G. (2016). Contextual factors affecting moral stress: A study of military and police officers. International Journal of Public Leadership, 12, 275–288. doi:10.1108/IJPL-04-2016-0019

- Jameton, A. (1984). Nursing practice: The ethical issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall4.

- Jinkerson, J. D. (2016). Defining and assessing moral injury: A syndrome perspective. Traumatology, 22(2), 122–130. doi:10.1037/trm0000069

- Jolly, R. (1996). Changing step. London, UK: Brassey’s Ltd.

- Koenig, H. G., Boucher, N. A., Oliver, J. P., Youssef, N., Mooney, S. R., Currier, J. M., & Pearce, M. (2017). Rationale for spiritually oriented cognitive processing therapy for moral injury in active duty military and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(2), 147–153. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000554

- Kopacz, M. S., & Connery, A. L. (2015). The veteran spiritual struggle. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 2(1), 61–67. doi:10.1037/scp0000059

- Lagacé-Roy, D. (2007). Military ethics: A case study method. In J. Toiskallo (Ed.), Ethical education in the military: What, how and why in the 21st century? (pp. 110–123). Helsinki, Finland: National Defence University.

- Larsson, G., Nilsson, S., & Waaler, G. (2018). Moralisk stress - profesionella möten med moraliskt laddade situasjonar. Necesse, 13(1), 32–37. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11250/2502097

- Lazarus, R. A. (1991). Cognition and motivation in emotion. American Psychologist, 46(4), 352–367. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.46.4.352

- Lifton, R. J. (1992). Home from the war: Learning from Vietnam veterans (with a new preface and epilogue on the Gulf war). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Litz, B. T., Stein, N., Delaney, E., Lebowitz, L., Nash, W. P., Silva, C., & Maguen, S. (2009). Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: A preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(8), 695–706. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Lutzén, K., & Kvist, B. E. (2012). Moral distress: A comparative understanding and inter-related concepts. HealthCare Ethics Committee (HEC) Forum: An Interprofessional Journal on Healthcare Institutions’ Ethical and Legal Issues, 24, 13–25.

- Maguen, S., & Litz, B. (2012). Moral injury in veterans of war. PTSD Research Quarterly, 23(1), 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003

- Maguen, S., & Litz, B. (2018). Moral Injury in the context of war (PTSD: National Center for PTSD). Retrieved from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/cooccurring/moral_injury_at_war.asp

- Maguen, S., Luxton, D. D., Skopp, N. A., Grahm, G. A., Reger, M. A., Metzler, T. J., & Marmar, C. J. (2011). Killing in combat, mental health symptoms, and suicidal ideation in Iraq Veterans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(4), 563–567. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.01.003

- McCarthy, J., & Gastmans, C. (2015). Moral distress: A review of the argument-based nursing ethics literature. Nursing Ethics, 22(1), 131–152. doi:10.1177/0969733014557139

- McLure, S. M., Botvinick, M. M., Young, N., Greene, J. D., & Cohen, J. D. (2007). Conflict monitoring in cognition-emotion competition. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 204–226). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Miller, R. W. (2014). Moral differences: Truth, justice and conscience in a world of conflict. Princeton, NJ: Princeton.

- Moon, Z. (2019). Warriors between worlds: Moral injury and identities in crisis. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Moore, B. A. (Ed.). (2012). Handbook of counseling military couples. New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Nash, W. P., Carper, T. L. M., Mills, M. A., Au, T., Goldsmith, A., & Litz, B. T. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury event scale. Military Medicine, 178(6), 646–652. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017

- Nilsson, S., Brandow, C., Ohlsson, A., & Larsson, G. (2017). Military leadership and emotion regulation in acute situations that contain moral dilemmas. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 8(4), 269. doi:10.1504/IJWOE.2017.089293

- Nilsson, S., Hyllengren, P., Ohlsson, A., Kallenberg, K., Waaler, G., & Larsson, G. (2015). Leadership and moral Stress: Individual reaction patterns among first responders in acute situations that involve moral stressors. Journal of Trauma & Treatment, 4, 261–271. doi:10.4172/2167-1222.S4-025

- Nilsson, S., Sjöberg, M., Kallenberg, K., & Larsson, G. (2011). Moral stress in international humanitarian aid- and rescue operations: A grounded theory study. Ethics and Behaviour, 21(1–20). doi:10.1080/10508422.2011.537570

- Richardson, R., Verweij, D., & Winslow, D. (2004). Moral fitness for peace operations. Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 32(1), 99–113. Retrieved from http://130.252.58.169/docview/206651054?accountid=8325

- Severinsson, E. (2008). Moral stress and burnout: Qualitative content analysis. Nursing & Health Sciences, 5(1), 59–66. doi:10.1046/j.1442-2018.2003.00135.x

- Shay, J. (2002). Odysseus in America: Combat trauma and the trails of homecoming. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Shay, J. (1994/2003). Achilles in Vietnam: Combat trauma and the undoing of character. New York, NY: Scribner.

- Shay, J., & Munroe, J. (1998). Group and milieu therapy for veterans with complex posttraumatic stress disorder. In P. A. Saigh & J. D. Bremner (Eds.), Posttraumatic stress disorder: A comprehensive text (pp. 391–413). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Silver, M. (2011). Our morality: A defense of moral objectivism. Philosophy Now, 83, 21–24.

- Smith-MacDonald, L. A., Morin, J.-S., & Brémault-Phillips, S. (2018). Spiritual dimensions of moral injury: Contributions of mental health chaplains in the Canadian armed forces. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9(592), 1–7. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00592

- Tick, E. (2005). War and the soul. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

- Vargas, A. F., Hanson, T., Kraus, D., Drescher, K. D., & Foy, D. W. (2013). Moral injury themes in combat veterans’ narrative responses from the National Vietnam Veterans’ readjustment study. Traumatology, 19(3), 243–250. doi:10.1177/1534765613476099

- Vieten, C., Scammell, S., Pierce, A., Pilato, R., Ammondson, I., Pargament, K. I., & Lukoff, D. (2016). Competencies for psychologists in the domains of religion and spirituality. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 3(2), 92–114. doi:10.1037/scp0000078

- Waaler, G., Larsson, G., & Nilsson, S. (2019). Voldsbruk, drap og livsfare. Norske og svenske krigserfaringer fra Afghanistan. Oslo, Norway: Cappelen-Damm.

- Waaler, G., Nilsson, S., Larsson, G., & Espevik, R. (2013). Ars vitam tollendi – Kunsten att slå i hjel [Ars vitam tollendi – The art of killing]. PACEM, 16, 5–26.

- Wahlberg, Å. (2018). Second victims in Swedish obstetrics (doctoral thesis, Uppsala University, Sweden). Acta Universitatis Upsalensis, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Whittaker, B. A., Gillum, D. R., & Kelly, J. M. (2018). Burnout, moral distress and job turnover in critical care nurses. International Journal of Studies in Nursing, 3(3), 108–121. doi:10.20849/ijsn.v3i3.516

- Wilkinson, J. M. (1987). Moral distress in nursing practice: Experience and effect. A Journal of Advanced Nursin, 23(1), 16–29. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6198.1987.tb00794.x

- Wortmann, J. H., Eisen, E., Hundert, C., Jordan, A. H., Smith, M. W., Nash, W. P., & Litz, B. T. (2017). Spiritual features of war related moral injury: A primer for clinicians. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 4(4), 249–261. doi:10.1037/scp0000140

- Yeterian, J., Berke, D., Rosenthal, J., & Litz, B. (in press). Moral injury in military service members and veterans. In E. Seamone, C. Finkelstein, & S. Xenakis (Eds.), Preventing and treating the invisible wounds of war: Combat trauma and psychological injury. Oxford University Press.