ABSTRACT

Mental health officers (MHO) in the military often encounter soldiers expressing distress, manifested in threats and attempts at self-harm and suicide. While these behaviors are a significant stressor for therapists, they may also be an opportunity for posttraumatic growth (PTG). We aimed to examine whether the relatively frequent exposure of MHO to soldiers who report thoughts, intentions, and attempts at self-harm and suicide is related to their PTG, as well as tested the contribution of cognitive variables (the centrality of the event and the challenge to core beliefs), and a trait not previously considered in this context, i.e. self-compassion to PTG. Self-report questionnaires were completed by130 Israeli army MHO. Of these, 98.5% reported that they are exposed to self-harm. The questionnaires were collected between the years 2020–2021. The findings show a positive linear relationship, as well as a curvilinear relationship, between PTG and exposure to expressions of self-harm and suicide, the centrality of the event, and the challenge to core beliefs. In addition, self-compassion served as a moderator in the association between exposure and PTG. The study validates the PTG model in a population that has not previously been studied in this context, and may lead to a broader understanding of PTG in this context. They may help in designing dedicated training programs for therapists dealing with reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior.

What is the public significance of this article?— During their clinical work, therapists often treat patients in distress to the point of threats of self-harm or suicide. Exposure to reports of such behaviors can have an emotional impact on the therapist (McAdams & Foster, Citation2000), with most studies in the field considering its negative effects. However, a number of studies have investigated the positive outcome of posttraumatic growth among therapists such as psychologists (Tominaga et al., Citation2019), psychiatric nurses (Zerach & Ben-Itzhak Shalev, Citation2015), psychiatrists (Dar & Iqbal, Citation2020), and doctors in general (Abu-Sharkia & Taubman – Ben-Ari, Citation2020; Dar & Iqbal, Citation2020). The current study considers a population never previously examined, military mental health officers)MHOs), exploring the possibility of PTG among clinicians in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), who often encounter soldiers reporting threats of self-harm, non-suicidal self-harm, suicidal thoughts, and suicide attempts. Moreover, it aims to examine the contribution of cognitive and personality characteristics to the PTG of these officers. The study relies on the model of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018), and seeks to expand it by adding a personality characteristic never before addressed, namely, self-compassion.

Therapeutic work with patients reporting self-harm and suicidal behavior

Self-harm is defined as the destruction of one’s own body tissues directly and intentionally (Nock & Favazza, Citation2009). It refers to all types of intentional self-injurious behavior (i.e., non-suicidal self-harm, intentional self-harm, and suicide attempts), and is a significant risk factor for later suicide (Carroll et al., Citation2014; Prinstein et al., Citation2008).

Suicide is defined as an act resulting in death. However, suicidal behavior refers to a wide range of different behaviors with different outcomes, including suicidal thoughts, self-destructive behaviors, suicidal gestures, and suicide attempts of varying degrees of severity (Apter et al., Citation2008). Suicidal behavior is regarded as one of the highest stress factors in the work of therapists (Deutsch, Citation1984; Norheim et al., Citation2013). A patient’s suicide, as well as the care of a suicidal patient, has been found to evoke stress similar to the loss of a family member and to arouse emotions such as shock, grief, and guilt (Ellis & Patel, Citation2012), anger and sadness (De Lyra et al., Citation2021; Sandford et al., Citation2021), stress and anxiety (McAdams & Foster, Citation2000), and exhaustion and deep depression (Foley & Kelly, Citation2007). Therapists who have experienced a patient’s suicide report emotional burnout, questions about professional identity, a decreased sense of competence, and anxiety about professional repercussions or legal action (Sanders et al., Citation2005; Tillman, Citation2006). This experience thus has considerable and lasting emotional consequences, and constitutes a traumatic life event for the therapist (Sandford et al., Citation2021).

In the IDF, in which military service is mandatory for men and women at the age of 18, MHOs frequently meet with soldiers who report suicide attempts and self-harm, and therefore routinely engage in suicide risk assessment. Military service exerts a lot of mental pressure on the young men and women in the army. The soldiers are forced to deal with a rigid hierarchical system at a time when they are struggling to achieve independence, a limited capacity for support from family and friends (Bodner et al., Citation2007), and access to firearms, which is a major risk factor for suicide (Mann & Michel, Citation2016). The stress places this population at particularly high risk for self-harming behaviors, suicide attempts, and suicide. While MHOs’ preoccupation with dangerous behavior may affect them both personally and professionally, the literature shows that exposure to stress may also lead to PTG.

Posttraumatic growth

The term posttraumatic growth (PTG) (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation1996) refers to a positive psychological change that the individual experiences after dealing with a stressful event and is expressed as a positive transformative development in functioning or a change in the individual’s perception of life as manifested in cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains, such as changes in health and social relationships, and a life perspective that reduces stress (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018). In the past, PTG was considered the result of dealing with extreme stress and/or traumatic events (Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006). Over the years, however, there has been increasing understanding that a traumatic event or significant crisis is not required for growth, but it may also be triggered by life events characterized by more moderate levels of stress (Taubman – Ben-Ari et al., Citation2013). For example, it has been shown that PTG (also known as personal growth, PG) may emerge in the wake of the work of security and rescue forces (Paton, Citation2005), social workers (Ben-Porat, Citation2015), and medical teams (Abu-Sharkia et al., Citation2020; Feingold et al., Citation2022; Taubman – Ben-Ari & Weintroub, Citation2008).

Therapists who work with patients with PTSD also report not only vicarious posttraumatic symptoms, but also positive changes in their own personality and perceptions. They note that they have become more sensitive, compassionate, and patient, and have developed an appreciation for the resilience of the individual (Arnold et al., Citation2005). Therapists exposed through their patients to traumatic stories also report growth, reflected in a positive assessment of themselves, such as the feeling that they have become more professional and developed a higher awareness of social justice (Cohen & Collens, Citation2013). Moreover, the literature shows that women tend to experience more growth than men, perhaps because of their greater ability and willingness to express emotions (Kalaitzaki, Citation2021; Vishnevsky et al., Citation2010).

Tedeschi et al. (Citation2018) model of results from a challenge to the individual’s basic schemas, along with the cognitive perception that the event is central to their life, thereby undermining these schemas. The current study therefore examines MHOs’ perception of the centrality of the event of exposure to reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior, and the extent to which this kind of exposure challenges their core beliefs. In addition, as noted above, we seek to expand the original PTG model by examining a personality variable that may help to explain PTG in this context, and may potentially moderate the relationship between exposure and PTG, namely, self-compassion.

Cognitive perceptions and posttraumatic growth

The challenge to core beliefs

Life events that arouse high stress may sometimes challenge the individual’s perceptions and assumptions of the world, even if the events themselves are not traumatic (Cann et al., Citation2009). Core beliefs are a broad group of fundamental notions that include, among other things, how we believe people should behave, how events should unfold, and our ability to influence events (Cann et al., Citation2009). A threat to an individual’s core beliefs may not only have negative consequences, but may also enable positive processes, such as PTG (Linley & Joseph, Citation2004; Phelps et al., Citation2008). The more significant individuals perceive the upheaval in their core beliefs, the higher the PTG they may experience. In other words, the cognitive work of the individual after a stressful event, together with the attempt to reconstruct their core beliefs, may lead to PTG (Cann et al., Citation2009). Indeed, reexamination of one’s world views after a stressful event has been found to be the most significant predictor of growth (Freedle & Kashubeck-West, Citation2021; Taku et al., Citation2015), indicating that the ability to establish a new and functional set of world views is critical to the experience of PTG (Mazor et al., Citation2020).

Centrality of the event

The centrality of the event refers to the extent to which the individual attributes meaning and significance to a stressful event in their life, and its impact on their identity. When an event is regarded as a major turning point in a person’s narrative, it may affect how they subsequently see themselves (Berntsen & Rubin, Citation2006; Boals, Citation2010). While the perception of the centrality of the event may predict difficulties such as depression or PTSD (Groleau et al., Citation2013), dealing with it may also lead to PTG (Boals & Schuettler, Citation2011; Groleau et al., Citation2013). It has been found that the more central the person perceives the traumatic event to be in their life, the more PTG they may experience (Groleau et al., Citation2013; Schuettler & Boals, Citation2011). In this sense, the perception of the centrality of the event is customarily considered a paradoxical variable or a “double-edged sword” (Boals & Schuettler, Citation2011; Steinberg et al., Citation2021), as it is argued that the degree to which the perception of the centrality of the event leads to either distress or growth depends on how it is interpreted by the individual (Steinberg et al., Citation2021).

Personality characteristics and posttraumatic growth

Self-compassion

Self-compassion (Neff, Citation1995) refers to individuals’ compassion for themselves, and consists of three components: kindness toward the self, that is, the absence of judgment or criticism; humanity, or the ability to tell yourself at difficult times that everyone makes mistakes and faces the same challenges in life; and mindfulness, or the willingness to be aware of your feelings and thoughts in stressful situations (Neff, Citation1995). Self-compassion makes it possible to deal with feelings of anxiety (Bluth et al., Citation2017), and is an important and protective component in emotional regulation and mental health (Bakker et al., Citation2019; Tiwari et al., Citation2020). People with higher self-compassion are better able to deal with stressful situations (Leary et al., Citation2007), and have a reduced risk of experiencing secondary traumatization or burnout (Beaumont et al., Citation2015; Gerber & Anaki, Citation2021; Jaber et al., Citation2016; Thompson et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, people with high self-compassion are more likely to experience growth (Munroe et al., Citation2022; Umandap & Teh, Citation2020). Self-compassion reduces one’s tendency to over-identify with negative emotions through positive framing and thus promotes growth (Munroe et al., Citation2022). Thus, therapists who are characterized by higher self-compassion cope better with stress in their work (Boellinghaus et al., Citation2014), adapt more, and tend to examine situations and difficulties in a balanced way and use them as an opportunity for growth (Chan et al., Citation2020; Finlay-Jones et al., Citation2015). As a result, they may experience more PTG since they can accept the existence of crisis as part of life, reinterpret negative events, and experience meaning (Wong & Yeung, Citation2017). In other words, self-compassion can provide therapists with a resource that will protect them from stress arising from the care of their patients (Braehler & Neff, Citation2020). Moreover, it has been found that self-compassion moderates the relationship between stress and burnout in nurses (Dev et al., Citation2020).

The current study

The role of MHO entails pressure and is often characterized by emotionally charged meetings with soldiers and commanders, both in routine times and during emergencies. The need to respond and make decisions while managing risk increases the pressure, especially in cases of exposure to events on the continuum of self-destruction, which may arouse a variety of negative feelings (Deutsch, Citation1984). In addition, the literature indicates that dealing with their patients’ hardships may lead to PTG among therapists (Cohen & Collens, Citation2013). However, the relationship between exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior and the possibility of PTG among military therapists, whose work makes them particularly prone to this exposure, has never previously been examined. Based on the theoretical model of PTG, the present study examined the contribution of the perception of the centrality of the event (Boals & Schuettler, Citation2011) and the challenge to core beliefs (Taku et al., Citation2015), as well as self-compassion (Neff, Citation1995), to the PTG of MHOs in the Israeli army.

On the basis of the literature, the following hypotheses were formulated:

A positive linear relationship will be found between the intensity of exposure of MHOs to self-harm and suicidal behavior among soldiers and their PTG, so that the greater the exposure, the greater the PTG the MHO will report. In addition, a curvilinear relationship will be found between the intensity of the MHO’s exposure and PTG, so that at moderate levels of exposure, PTG will be higher, while at high and low levels of exposure, PTG will be lower.

A positive relationship will be found between MHOs’ perception of the centrality of exposure to self-harm and suicidal thoughts and PTG, so that the more central the MHO perceives the exposure to be, the more PTG they will report.

A positive relationship will be found between the challenge to MHOs’ core beliefs following exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior and PTG, so that the stronger the challenge, the more PTG they will report.

A positive relationship will be found between self-compassion and PTG, so that the higher the self-compassion, the higher the PTG. In addition, self-compassion will moderate the relationship between exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior and PTG, so that at low levels of self-compassion, the relationship between the two variables will be positive, while at high levels of self-compassion, the relationship between them will be weaker.

Furthermore, the unique and combined contribution of all the research variables to the PTG of MHOs exposed to the self-harm or suicidal behavior of their patients was examined exploratively.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 130 MHOs in the IDF, most of whom were social workers (83.1%), and the rest were psychologists (15.4%) or psychiatrists (1.5%). Seniority in the IDF ranged from two months to 24 years and two months (M = 61.49 SD = 51.89 months). Age ranged from 25 to 48 years (M = 33.6, SD = 4.53). Seventy percent of the respondents were women and 30% were men. In addition, 77.7% were married or in a relationship. In terms of education, 28.5% had a BA, 67.7% had or were studying for an MA, and 3.8% had a doctorate or were doctoral students.

Procedure

After receiving approval from the University Review Board, the first author received a list from the IDF of all the MHOs currently serving in the army. All the MHOs received a message describing the study and asking them to complete the self-report questionnaire in the attached link. It was explained that the data was intended for research purposes only, and the confidentiality of their responses was guaranteed. It was also made clear that participation in the study was voluntary, that they could withdraw at any time, and that no identifying information would be stored in the data file.

Of the 260 questionnaires distributed, 185 were returned. The final sample consisted of 130 MHOs who had completed the questionnaire in full. An average of 17 minutes was required to complete the questionnaire.

Instruments

Posttraumatic Growth Inventory-Short Form (PTGI-SF; Cann et al., Citation2010) was used to assess positive outcomes that may occur as a result of trauma and crisis. It contains 10 items which refer to the five dimensions of PTG: recognition of new possibilities and change in priorities; change in relationships with others; awareness of personal strengths; spiritual development; and greater appreciation of life. The respondents were asked to rate the degree to which they have experienced the change in each item on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (to a great extent). The internal reliability of the original inventory was α = 0.89 and it was α = 0.90 in the current study. Responses to all items were averaged to produce a general PTG score, with higher scores indicating greater PTG.

Core Beliefs Inventory (CBI; Cann et al., Citation2009) was used to examine change in spiritual beliefs, human nature, relationships, personal strengths and weaknesses, and meaning in life after dealing with a stressful event. The participants were asked to reflect on their exposure to reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior and consider how much it challenged their core beliefs in these domains. The questionnaire consists of 9 items (e.g., “Because of this exposure, I thoroughly examined how much I believe that the things that happen to people are fair”). Responses were indicated on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The reliability of the original instrument was α = 0.82 and it was α = 0.91 in the present study. The responses to all items were averaged to produce a general score, with higher scores indicating a greater challenge to the participant’s core beliefs.

Centrality of Event Scale (CES; Berntsen & Rubin, Citation2006) was used to assess the extent to which the memory of a stressful event creates a reference point for personal identity and gives meaning to later events in life. The scale contains 7 items referring to 2 situations: physical threat and social threat (e.g., “I feel that this event has become a part of my identity”). The respondents were asked to mark their responses on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 completely agree). Since the study was aimed at examining the response to repeated events, it was explained that the term “event” refers to routine exposure to reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior. The reliability of the original instrument was α = 0.88. In the present study it was α = 0.87. A general score was calculated for each participant by totaling their responses to all items, so that the higher the score, the more central the exposure was perceived.

Self-compassion Scale-Short Form (SCN-SF; Raes et al., Citation2011) was used to assess the degree of compassion the respondents feel toward themselves. It consists of 12 items (shortened from the original 26) tapping the three dimensions of self-compassion: kindness toward the self; humanity; and mindfulness (e.g., “When I fail in something that is important to me, I am filled with feelings of inadequacy”). The participants were asked to indicate the extent to which the statement in each item applies to them. Responses were marked on a Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (very often). The developers report an internal reliability of α = 0.86. In the current study it was α = 0.84. After reverse coding the relevant items (1, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12), responses to all items were averaged to produce a general score, with higher scores indicating greater self-compassion.

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to obtain personal and occupational details, including age, sex, profession (psychologist, social worker, psychiatrist), education (BA, MA, doctorate), and seniority. In addition, it tapped the frequency of exposure to cases or threats of self-harm and suicidal behavior (less than once a week (41.5%), once a week (30.8%), more than once a week (27.7%)), as well as the number of cases of actual self-injury and suicide in the unit in the preceding six months (M = 13.4 SD = 18.7). 98.5% of the mental health officers in the study reported that they are exposed to self-harm.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS software. First, the correlations between the research variables were calculated. A 6-step hierarchical regression was then performed to examine the contribution of the independent variables to the dependent variable (PTG), the possibility of a curvilinear relationship between exposure and PTG (Hypothesis 2), and whether self-compassion moderates this association (Hypothesis 4). The background variables were entered in Step 1, and the frequency of exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior in Step 2. In Step 3, the squared exposure was entered in order to examine the possibility of a curvilinear relationship between exposure and PTG. The cognitive variables of centrality of the event and challenge to core beliefs were entered in Step 4, and self-compassion was entered in Step 5. In Step 6, the interaction between self-compassion and exposure was introduced in order to examine the possibility that self-compassion serves as a moderating variable. The steps in the regression were designed to control for the background variables, and accord with the rationale of the theoretical model of PTG. The interactions were tested using Hayes Process Macro Model 4 and Model 5 (Hayes, Citation2013).

Results

Frequency of exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior

Exposure to threats of self-harm and suicidal behavior, as well as actual suicide attempts, were reported by 98.5% of the MHOs in the sample. In terms of frequency, 41.5% experienced such exposure less than once a week, 30.8% once a week, and 27.7% more than once a week. The average number of cases of self-inflicted injuries and suicide attempts that had occurred in their unit in the past six months was 13.4 (SD = 18.7).

Associations between the research variables

The results of the Pearson correlations, calculated to examine the associations between the independent and dependent variables, appear in . As can be seen in the table, contrary to Hypothesis 1, no association was found between the level of exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior and PTG. However, in confirmation of Hypothesis 2, a moderate and significant positive correlation was found between the perceived centrality of the exposure and PTG, so that the more central the MHO perceived this exposure to be, the more PTG they reported. Hypothesis 3 was also confirmed, with a positive, moderate significant correlation found between the perceived challenge to core beliefs and reported PTG. Contrary to expectations (Hypothesis 4) however, no significant association emerged between self-compassion and PTG.

Table 1. Pearson correlations between study variables.

In addition, a positive and linear relationship was found between the centrality of the event and the challenge to core beliefs. In other words, the higher the perception of the centrality of the event, the higher the perceived challenge to core beliefs.

Contribution of the independent variables to posttraumatic growth

presents the results of the hierarchical regression examining the unique and combined contribution of the research variables to posttraumatic growth. The model explained a total of 40.2% of the variance in PTG.

Table 2. Results of the regression analysis for the variance in posttraumatic growth.

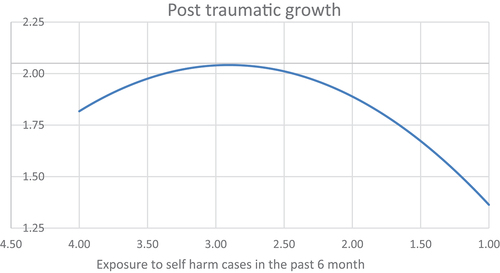

The background variables entered in Step 1 contributed 1.3% to the explained variance, although no significant associations were found between any specific variable and PTG. In Step 2, exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior contributed another 3.8% to the explained variance, with greater exposure contributing to higher PTG. In Step 3, the squared exposure (curvilinear association) explained an additional 3% of the variance. This squared relationship is shown in , which reveals that PTG is a reaction to exposure up to an exposure value of 3.00. Below and above this value, the association between exposure and PTG is negative, indicating that PTG is highest at moderate levels of exposure, and lower at low and high levels.

In Step 4, the cognitive variables of challenge to core beliefs and centrality of the event explained 29.2% of the variance. Specifically, it was found that the perceived challenge to core beliefs was positively related to PTG. Self-compassion in Step 5 did not significantly contribute to the explanation of the variance in PTG. However, the interaction between self-compassion and exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior in Step 6 explained 2.9% of the variance, indicating that self-compassion has a moderating effect on the linear association between exposure and PTG. Analysis of the source of the interaction which were analyzed with Hayes Process Macro Model 4 and Model 5 (Hayes, Citation2013), is presented in , which shows that only when self-compassion is low, does this variable play a moderating role (simple slope = 0.20, p < .05). This effect is presented in , which illustrates how the relationship between exposure and PTG changes at different levels of self-compassion. Thus, when self-compassion is low, the relationship between exposure and PTG is close to linear and is associated with high levels of growth. When self-compassion is higher, up to a point of about 1.50, the direction is reversed, but is not significant.

Figure 2. Sources of the interaction between exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior and self-compassion and its effect on PTG.

Table 3. Source of the interaction between exposure and self-compassion and its effect on posttraumatic growth.

Discussion

Although MHOs are frequently required to assess the risk of self-harm and suicide as part of their work, this population has received little, if any, research attention. The present study therefore examined the consequences of exposure to reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior for PTG, based on Tedeschi and Calhoun’s posttraumatic growth model (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018). To this end, we explored the contribution of the cognitive variables of centrality of the event and challenge to core beliefs and the personality variable of self-compassion to the PTG of MHOs in the Israeli army.

The results show that PTG is high at a moderate level of exposure, but low at high or low levels of exposure. It is possible that low levels of exposure are not experienced with the intensity that leads to PTG. Moreover, therapists who choose to work in the military and undergo a long process of acceptance that acquaints them with the role and its challenges may have the personal qualities to deal with it in a way that does not cause unusual distress. Indeed, a study that examined personal growth among doctors and nurses suggests that staff members who choose to work in an environment where the daily routine brings the professional into contact with death are likely to be characterized by certain traits and coping strategies that cause them to perceive their work as not unusually stressful or distressing. Consequently, they appear not to experience personal growth (Taubman – Ben-Ari & Weintroub, Citation2008). On the other hand, PTG may not be possible at high levels of exposure because it may produce distress in the form of secondary traumatization. In a study conducted among medical personnel, it was found that personal growth among those who were exposed to a high frequency of illness and mortality was lower than among those who were exposed to new life in the delivery room. The authors suggest that bringing new life into the world is usually characterized by positive emotions, so that when the staff is exposed to morbidity or mortality, the effects are more radically negative (Abu-Sharkia et al., Citation2020). Moreover, it has been found that when distress levels are high, there is a decrease in the experience of growth (Ben-Porat, Citation2015). This may be similar to the situation of soldiers, who generally constitute a young and healthy population. Thus, when soldiers injure themselves or take their own life, it may cause greater distress among MHOs, therefore not allowing for the development of PTG.

In addition, a positive relationship was found between the suicidal perceived centrality of the exposure and its challenge to the core beliefs of the MHO on the one hand, and PTG on the other. These findings are in line with the PTG model (Tedeschi et al., Citation2018), in which these cognitive variables are significant components on the way to growth after dealing with stressful events. Thus, exposure to death, injury, and distress is reflected in the perception of its centrality in the individual’s life and its challenge to their core beliefs. Our findings are also consistent with previous studies indicating a positive association between the perceived centrality of the event and PTG (Brooks et al., Citation2017; Cann et al., Citation2011; Clauss et al., Citation2021; Groleau et al., Citation2013), as well as between the challenge to core beliefs and PTG (Cann et al., Citation2009; Linley & Joseph, Citation2004). Furthermore, soldiers who are in distress operate within a rigid, intensive framework, by obligation rather than by choice, which may also provide them with the means to implement their thoughts of self-harm or suicide. These circumstances strengthen the responsibility of MHOs for risk management and the need for an immediate professional response, increasing the pressure on them. This situation may be reflected in their perception of the centrality of the event and its challenge to their core beliefs, which in turn may promote PTG.

In contrast to expectations and reports in the literature (Finlay-Jones et al., Citation2015; Leary et al., Citation2007), no direct linear relationship was found here between self-compassion and PTG. However, a more complex relationship emerged, whereby self-compassion moderated the association between exposure and PTG, so that when self-compassion was low, higher levels of exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior were associated with higher PTG. This effect was not found at high levels of self-compassion. In other words, self-compassion appears to moderate the damaging effect of stress, indicating the central role of self-compassion as a protective factor. The literature shows that among therapists, dealing with trauma and suicide is characterized by distress that manifests itself in stress, burnout, and poor motivation to treat these patients, and challenges their sense of competence and professional responsibility (McAdams & Foster, Citation2000; Sanders et al., Citation2005). It may be assumed that MHOs who display high self-compassion have the ability to be attentive, forgiving, and humane toward themselves, and this trait constitutes a shield against the distress that arises when meeting with soldiers who express difficulties to the point of danger, regardless of the amount of exposure. Therefore, they do not experience stress at a level that enables the development of PTG (Beaumont et al., Citation2015; Bluth et al., Citation2017; Leary et al., Citation2007; Neff et al., Citation2007).

Limitations and recommendations for future research

The current study has several limitations that should be noted. First, it is a correlational cross-sectional study in which the data was collected at a single point in time, and it is therefore impossible to draw conclusions about causality. Second, the number of women is much greater than the number of male participants. While this is a correct reflection of the reality, the results may better suit women MHOs. Moreover, we could not learn about changes in PTG over time among MHOs. A longitudinal study that examines the degree of PTG at additional time points since their recruitment could shed more light on its trajectory. In addition, future studies could examine other cognitive, personal, and environmental variables that may contribute to PTG in this population., It is worth noting that MHOs face additional pressures, such as the demands of commanders, the hardships of non-suicidal soldiers, the impact of moral injury and difficulties related to the features of the military setting, which may also play a role in the experience of PTG. Furthermore, in the current study, negative variables such as PTSD and poor adjustment were not examined. We recommend investigating these variables in future studies. In addition, despite efforts to reach the entire population of MHOs, we managed to recruit only about half. The size of the sample may therefore have limited the statistical models that could be tested in the study. However, the decision to conduct a study among MHOs, even though they are a relatively small group, was based on the fact that they constitute a group of therapists with relatively unique characteristics, such as working in a hierarchical framework, the focus mainly on young patients, the relatively high exposure to self-harm and suicidal behavior, Nevertheless, the use of a larger sample in a future study could produce further insights into the PTG of MHOs.

Moreover, the study relied on self-report measures, raising the possibility of a social desirability bias, so that the participants’ responses may only partially reflect their actual attitudes, feelings, and experience. However, since all the variables in this study relate to the internal feelings and attitudes of the respondents, there was no other way to evaluate them. Furthermore, all the participants were MHOs in the IDF, and it may therefore be difficult to generalize the findings to therapists in other military settings. Moreover, the vast majority of the participants belonged to the professions of social work and psychology, with very few psychiatrists. Future studies might attempt to recruit more psychiatrists, affording an opportunity to gain a greater understanding of the PTG of MHOs from this profession as well.

In addition, no distinction was made here between suicidal behavior and self-harm (which self harm may not be associated with suicidal intent), or between thoughts, intentions, and actual attempts. A study that distinguishes between these behaviors might shed further light on the processes of distress and PTG among caregivers in general, and MHOs in particular.

Conclusions and implications of the study

This study contributes to the literature on both the theoretical and practical levels. In theoretical terms, it reveals factors that contribute to PTG among MHOs, a population that is routinely exposed to reports of self-harm and suicidal behavior. On the practical level, the findings of the study may help professionals (researchers, instructors, etc.) to identify the effects of this exposure and encourage the MHOs’ use of the cognitive and personal resources that promote the experience of PTG, such as self-compassion. It goes without saying that the therapist’s own well-being affects their willingness to treat their patients and the quality of care they provide.

In addition, the role of the MHO is intensive and entails a great deal of personal, moral, and professional responsibility for the soldiers they treat. Accordingly, the selection and acceptance procedure for the position consists of several stages, including tests and interviews. The findings of this study may help to identify the resources and personal and cognitive skills available to the candidates that will better enable them to cope with this demanding role.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study was conducted in compliance with ethical standards.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abu-Sharkia, S., Taubman – Ben-Ari, O., & Mofareh, A. (2020). Secondary traumatization and personal growth of healthcare teams in maternity and neonatal wards: The role of differentiation of self and social support. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(2), 283–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/NHS.12710

- Apter, A., King, R. A., Bleich, A., Fluck, A., Kotler, M., & Kron, S. (2008). Fatal and non-fatal suicidal behavior in Israeli adolescent males. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811110701798679

- Arnold, D., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R., & Cann, A. (2005). Vicarious posttraumatic growth in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167805274729

- Bakker, A. M., Cox, D. W., Hubley, A. M., & Owens, R. L. (2019). Emotion regulation as a mediator of self-compassion and depressive symptoms in recurrent depression. Mindfulness, 10(6), 1169–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1072-3

- Beaumont, E., Durkin, M., Hollins Martin, C. J., & Carson, J. (2015). Measuring relationships between self-compassion, compassion fatigue, burnout and well-being in student counsellors and student cognitive behavioural psychotherapists: A quantitative survey. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12054

- Ben-Porat, A. (2015). Vicarious post-traumatic growth: Domestic violence therapists versus social service department therapists in Israel. Journal of Family Violence, 30(7), 923–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10896-015-9714-X

- Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2006). The centrality of event scale: A measure of integrating a trauma into one’s identity and its relation to post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(2), 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.009

- Bluth, K., Campo, R. A., Futch, W. S., & Gaylord, S. A. (2017). Age and gender differences in the associations of self-compassion and emotional well-being in a large adolescent sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 840–853. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0567-2

- Boals, A. (2010). Events that have become central to identity: Gender differences in the centrality of events scale for positive and negative events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 24(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1548

- Boals, A., & Schuettler, D. (2011). A double-edged sword: Event centrality, PTSD and posttraumatic growth. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 25(5), 817–822. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1753

- Bodner, E., Iancu, I., Sarel, A., & Einat, H. (2007). Efforts to support special-needs soldiers serving in the Israeli Defense Forces. Psychiatric Services, 58(11), 1396–1398. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1396

- Boellinghaus, I., Jones, F. W., & Hutton, J. (2014). The role of mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation in cultivating self-compassion and other-focused concern in health care professionals. Mindfulness, 5(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0158-6

- Braehler, C., & Neff, K. (2020). Self-compassion in PTSD. In M. T. Tull & N. A. Kimbrel (Eds.), Emotion in posttraumatic stress disorder: Etiology, assessment, neurobiology, and treatment (pp. 567–596). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816022-0.00020-X

- Brooks, M., Graham-Kevan, N., Lowe, M., & Robinson, S. (2017). Rumination, event centrality, and perceived control as predictors of post-traumatic growth and distress: The cognitive growth and stress model. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(3), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12138

- Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Kilmer, R. P., Gil-Rivas, V., Vishnevsky, T., & Danhauer, S. C. (2009). The core beliefs inventory: A brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 23(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800802573013

- Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Taku, K., Vishnevsky, T., Triplett, K. N., & Danhauer, S. C. (2010). A short form of the posttraumatic growth inventory. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 23(2), 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800903094273

- Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., Triplett, K. N., Vishnevsky, T., & Lindstrom, C. M. (2011). Assessing posttraumatic cognitive processes: The event related rumination inventory. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 24(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2010.529901

- Carroll, R., Metcalfe, C., & Gunnell, D. (2014). Hospital presenting self-harm and risk of fatal and non-fatal repetition: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS, 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944

- Chan, B. S. M., Deng, J., Li, Y., Li, T., Shen, Y., Wang, Y., & Yi, L. (2020). The role of self‐compas‐ sion in the relationship between post‐traumatic growth and psycho‐ logical distress in caregivers of children with autism. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 29(6), 1692–1700. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01694-0

- Clauss, K., Benfer, N., Thomas, K. N., & Bardeen, J. R. (2021). The interactive effect of event centrality and maladaptive metacognitive beliefs on posttraumatic stress symptoms and posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 13(5), 596. https://doi.org/10.1037/TRA0001010

- Cohen, K., & Collens, P. (2013). The impact of trauma work on trauma workers: A metasynthesis on vicarious trauma and vicarious posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 5(6), 570–580. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030388

- Dar, I. A., & Iqbal, N. (2020). Beyond linear evidence: The curvilinear relationship between secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth among healthcare professionals. Stress and Health, 36(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1002/SMI.2932

- De Lyra, R. L., McKenzie, S. K., Every-Palmer, S., Jenkin, G., & Sar, V. (2021). Occupational exposure to suicide: A review of research on the experiences of mental health professionals and first responders. PLOS , 16(4), e0251038. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251038

- Deutsch, C. J. (1984). Self-reported sources of stress among psychotherapists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 15(6), 833–845. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.15.6.833

- Dev, V., Fernando, A. T., III, & Consedine, N. S. (2020). Self-compassion as a stress moderator: A cross-sectional study of 1700 doctors, nurses, and medical students. Mindfulness, 11(5), 1170–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01325-6

- Ellis, T. E., & Patel, A. B. (2012). Client suicide: What now? Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 19(2), 277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.12.004

- Feingold, J. H., Hurtado, A., Feder, A., Peccoralo, L., Southwick, S. M., Ripp, J., & Pietrzak, R. H. (2022). Posttraumatic growth among health care workers on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JAD.2021.09.032

- Finlay-Jones, A. L., Rees, C. S., Kane, R. T., & van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. (2015). Self-compassion, emotion regulation and stress among Australian psychologists: Testing an emotion regulation model of self-compassion using structural equation modeling. PLOS, 10(7), e0133481. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133481

- Foley, S. R., & Kelly, B. D. (2007). When a patient dies by suicide: Incidence, implications and coping strategies. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(2), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.106.002501

- Freedle, A., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2021). Core belief challenge, rumination, and posttraumatic growth in women following pregnancy loss. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 13(2), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000952

- Gerber, Z., & Anaki, D. (2021). The role of self-compassion, concern for others, and basic psychological needs in the reduction of caregiving burnout. Mindfulness, 12(3), 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01540-1

- Groleau, J. M., Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2013). The role of centrality of events in posttraumatic distress and posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 5(5), 477–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028809

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press.

- Jaber, S., Chan, S., Jesse, M. T., Kaur, H., & Sangha, R. (2016). Self-compassion and empathy: Impact on burnout and secondary traumatic stress in medical training. Open Journal of Epidemiology, 6, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojepi.2016.63017

- Kalaitzaki, A. (2021). Posttraumatic symptoms, posttraumatic growth, and internal resources among the general population in Greece: A nation-wide survey amid the first COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Psychology, 56(5), 766–771. https://doi.org/10.1002/IJOP.12750

- Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Allen, A. B., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.887

- Linley, P. A., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

- Mann, J. J., & Michel, C. A. (2016). Prevention of firearm suicide in the United States: What works and what is possible. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(10), 969–979. https://doi.org/10.1176/APPI.AJP.2016.16010069

- Mazor, Y., Gelkopf, M., & Roe, D. (2020). Posttraumatic growth in psychosis: Challenges to the assumptive world. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 12(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000443

- McAdams, C. R., III, & Foster, V. A. (2000). Client suicide: Its frequency and impact on counselors. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 22(2), 107–121.

- Munroe, M., Al-Refae, M., Chan, H. W., & Ferrari, M. (2022). Using self-compassion to grow in the face of trauma: The role of positive reframing and problem-focused coping strategies. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 14(S1), S157–S164. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001164

- Neff, K. D. (1995). Buddhism in particular and Western psychology (Epstein). Self and Identity, 223–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860390209035

- Neff, K. D., Kirkpatrick, K. L., & Rude, S. S. (2007). Self-compassion and adaptive psychological functioning. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JRP.2006.03.004

- Nock, M. K., & Favazza, A. R. (2009). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Definition and classification. In M. K. Nock (Ed.), Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment (pp. 9–18). American Psychological Association.

- Norheim, A. B., Grimholt, T. K., & Ekeberg, O. (2013). Attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in outpatient clinics among mental health professionals in Oslo. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-90

- Paton, D. (2005). Posttraumatic growth in protective services professionals: Individual, cognitive and organizational influences. Traumatology, 11(4), 335–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/153476560501100411

- Phelps, L. F., Williams, R. M., Raichle, K. A., Turner, A. P., & Ehde, D. M. (2008). The importance of cognitive processing to adjustment in the 1st year following amputation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 53(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.53.1.28

- Prinstein, M. J., Nock, M. K., Simon, V., Aikins, J. W., Cheah, C. S. L., & Spirito, A. (2008). Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts following inpatient hospitalization. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.92

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the self-compassion scale. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702

- Sanders, S., Jacobson, J., & Ting, L. (2005). Reactions of mental health social workers following a client suicide completion: A qualitative investigation. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 51(3), 197–216. https://doi.org/10.2190/D3KH-EBX6-Y70P-TUGN

- Sandford, D. M., Kirtley, O. J., Thwaites, R., & O’Connor, R. C. (2021). The impact on mental health practitioners of the death of a patient by suicide: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(2), 261–294. https://doi.org/10.1002/CPP.2515

- Schuettler, D., & Boals, A. (2011). The path to posttraumatic growth versus posttraumatic stress disorder: Contributions of event centrality and coping. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 16(2), 180–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2010.519273

- Steinberg, M. H., Bellet, B. W., McNally, R. J., & Boals, A. (2021). Resolving the paradox of posttraumatic growth and event centrality in trauma survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress. https://doi.org/10.1002/JTS.22754

- Taku, K., Cann, A., Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2015). Core beliefs shaken by an earthquake correlate with posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy, 7(6), 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000054

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O., Findler, L., & Ben Shlomo, S. (2013). When couples become grandparents: Factors associated with the growth of each spouse. Social Work Research, 37(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svt005

- Taubman – Ben-Ari, O., & Weintroub, A. (2008). Meaning in life and personal growth among pediatric physicians and nurses. Death Studies, 32(7), 621–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180802215627

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

- Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., & Calhoun, L. G. (2018). Posttraumatic growth: Theory, research, and applications. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315527451

- Thompson, I., Amatea, E., & Thompson, E. (2014). Personal and contextual predictors of mental health counselors’ compassion fatigue and burnout. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(1), 58–77. https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.1.p61m73373m4617r3

- Tillman, J. G. (2006). When a patient commits suicide: An empirical study of psychoanalytic clinicians. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 87(1), 159–177. https://doi.org/10.1516/6UBB-E9DE-8UCW-UV3L

- Tiwari, G. K., Pandey, R., Rai, P. K., Pandey, R., Verma, Y., Parihar, P., Ahirwar, G., Tiwari, A. S., & Mandal, S. P. (2020). Self-compassion as an intrapersonal resource of perceived positive mental health outcomes: A thematic analysis. Mental Health, Religion and Culture, 23(7), 550–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1774524

- Tominaga, Y., Goto, T., Shelby, J., Oshio, A., Nishi, D., & Takahashi, S. (2019). Secondary trauma and posttraumatic growth among mental health clinicians involved in disaster relief activities following the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 33(4), 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1639493

- Umandap, J. D., & Teh, L. A. (2020). Self-compassion as a mediator between perfectionism and personal growth initiative. Psychological Studies, 65(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-020-00566-8

- Vishnevsky, T., Cann, A., Calhoun, L. G., Tedeschi, R. G., & Demakis, G. J. (2010). Gender differences in self-reported posttraumtic growth: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34(1), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01546.x

- Wong, C. C. Y., & Yeung, N. C. Y. (2017). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth: Cognitive processes as mediators. Mindfulness, 8(4), 1078–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12671-017-0683-4

- Zerach, G., & Ben-Itzhak Shalev, T. (2015). The relations between violence exposure, posttraumatic stress symptoms, secondary traumatization, vicarious post traumatic growth and illness attribution among psychiatric nurses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 29(3), 135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APNU.2015.01.002

- Zoellner, T., & Maercker, A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology — A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(5), 626–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008