Abstract

Several case reports have suggested that COVID-19 may increase the risk of gastrointestinal perforation. We report a case of a gastrointestinal perforation developing in a COVID-19 patient who presented due to injuries from a motor vehicle accident. On admission, the patient had elevated white blood cells, with neutrophilia and lymphopenia. Histological examination of tissue surrounding the perforation revealed extensive infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into the intestinal mucosa. These findings are consistent with SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, further pathophysiological studies are needed to assess the mechanisms by which COVID-19 may damage the gastrointestinal mucosa leading to gastrointestinal perforation.

Patients with the novel coronavirus known as SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 may present with various respiratory, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and neurologic diseases.Citation1 Gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, diarrhea, anorexia, abdominal pain, belching, and emesis, can occur in up to 50% of COVID-19 patients.Citation1 However, several case reports have suggested a potential role of COVID-19 in causing gastrointestinal perforations.Citation2–9 We report a case of a gastrointestinal perforation in a COVID-19 patient developing after a motor vehicle accident.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old woman presented to the hospital after being involved in a high-speed head-on motor vehicle collision with an 18-wheeler. The seat belt and airbag safely deployed, and there was no ejection or rollover during the incident. At the time of admission, she had a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 15 with a blood pressure of 110/75 mm Hg, heart rate of 89 beats/min, and body mass index of 34.75 kg/m2. The patient’s airway was intact with breath sounds present bilaterally. Peripheral circulation was present in all four extremities. The pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light (4 mm).

The patient had two large lacerations in the right periorbital region. An obvious open right ankle fracture with the talus extruded from the ankle wound and deformity to the right thumb were noted. Computed tomography (CT) of the head showed a large subgaleal hematoma with areas of active bleeding in the right frontoparietal region measuring up to 9 cm in the transverse and 2 cm in the vertical dimensions, without underlying calvarial fracture. No acute intracranial abnormality or fracture in the cervical spine was noted. CT of the body with contrast showed a small amount of free fluid in the right paracolic gutter and the cul-de-sac. There was a nondisplaced fracture of the left first rib. The patient had an elevated white blood cell count (14,760/mm3), with neutrophilia (12,720/mm3) and lymphopenia (1,170/mm3). She was also found to be positive for COVID-19 using the Abbott ID NOW COVID-19 rapid nucleic acid amplification test from nasal swab samples collected before surgery. The patient did not report any symptoms related to COVID-19 or recall any known exposures or contacts.

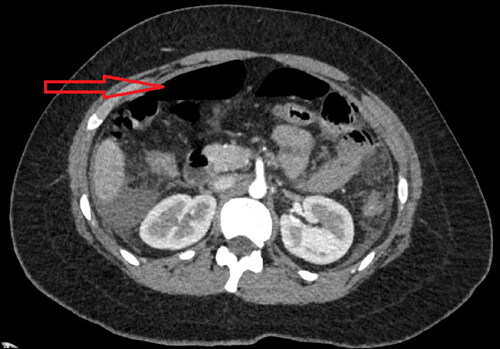

The patient underwent successful repair of the ankle fracture and thumb injury with no operative complications. However, upon recovery she complained of shortness of breath and left upper quadrant abdominal pain. A chest and abdominal CT demonstrated free air in the anterior abdomen, indicating development of pneumoperitoneum (), with moderate perihepatic and perisplenic ascites. A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed to identify the cause of the pneumoperitoneum. The small bowel was inspected and run from the ligament of Treitz distally, revealing an antimesenteric perforation in the jejunum, with no other perforations along the small bowel. The liver, gallbladder, and colon were inspected and revealed no abnormalities. The patient had a Meckel’s diverticulum with no associated areas of inflammation. The perforated small bowel was closed in order to minimize further contamination, after which a small bowel resection and a side-to-side anastomosis was performed.

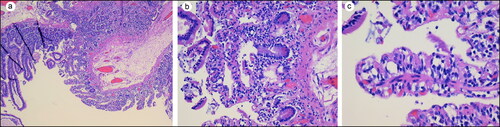

A jejunal specimen consisted of an unoriented looped segment of bowel that was anastomosed at the surgical margin. Two defects were identified, with the larger defect measuring 2 × 0.5 cm and the smaller defect measuring 1.2 × 0.3 cm. The serosa was pink to red and the overall measurement of the segment was 7.5 × 3 cm in diameter. The mucosa was pink to tan with hemorrhage around the two defected areas. Histological examination revealed effaced villi with lymphocytes and plasma cells infiltrating the mucosa; no microthrombi were observed (). Clindamycin and ciprofloxacin were administered to prevent infection. The patient was discharged after she tolerated a normal diet.

DISCUSSION

The possibility that COVID-19 infection causes or contributes to development of gastrointestinal perforations has been raised by several case reports affecting all age groups.Citation2–9 The most common causes proposed for COVID-19 gastric perforations include high-dose steroids, tocilizumab (an interleukin-6 inhibitor), stress-related mucosal damage, and small vessel thrombosis and nonocclusive mesenteric ischemia.Citation7–11 However, most authors suspect that angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), the primary cellular receptor for SARS-CoV-2, is involved since ACE-2 is highly expressed in the intestinal tract.Citation1–8,Citation12,Citation13 Consistent with this patient, several reports have documented neutrophilia and increased lymphocytes in COVID-19 patients.Citation14–17 Furthermore, autopsies of COVID-19 patients show neutrophil infiltration in pulmonary capillaries and alveolar spaces.Citation18 Although the mechanism underlying the increase in neutrophils and lymphocytes with COVID-19 remains unknown, an increase in neutrophils is known to increase oxidative stress and damage, including lipid peroxidation and DNA oxidation.Citation15 Depending on the severity of COVID-19, infiltration of inflammatory cells within the intestinal mucosa may increase oxidative stress and damage in gastrointestinal epithelial cells, which could contribute to intestinal perforation. Previous reports of intestinal perforation have not included histologic evaluation. However, there was extensive infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells into the intestinal mucosa surrounding the perforation. In vivo studies of mice infected with coronaviruses showed diffuse gastrointestinal damage, enterocyte desquamation, necrosis, and lymphocyte infiltration.Citation19 The gastrointestinal tract is abundant with a serine protease known as furin that separates the S-spike of SARS-CoV-2 to attach to the plasma membrane.Citation19 Furthermore, furin can enhance the pathogenicity of both viruses and micro-organisms; it is possible that the jejunal perforation observed in this patient may be due to a combination of increased immune response (lymphocytes and plasma cells) and furin protease activity in the mucosa.Citation20 Further pathophysiological studies are needed to assess the mechanisms by which COVID-19 may damage the gastrointestinal mucosa leading to gastrointestinal perforation.

- Kopel J, Perisetti A, Gajendran M, Boregowda U, Goyal H. Clinical insights into the gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(7):1932–1939. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06362-8.

- Bindi E, Cruccetti A, Ilari M, et al. Meckel’s diverticulum perforation in a newborn positive to Sars-Cov-2. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020;62:101641. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsc.2020.101641.

- Giuffrè M, Bozzato AM, Di Bella S, et al. Spontaneous rectal perforation in a patient with SARS–CoV-2 infection. JPM. 2020;10(4):157. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm10040157.

- Kangas-Dick A, Prien C, Rojas K, et al. Gastrointestinal perforation in a critically ill patient with COVID-19 pneumonia. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313X20940570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2050313X20940570.

- Karam C, Badiani S, Berney CR. COVID-19 collateral damage: delayed presentation of a perforated rectal cancer presenting as Fournier's gangrene. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90(7-8):1483–1485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.16104.

- Rohit G, Hariprasad CP, Kumar A, Kishor S, Kumar D, Paswan SS. Effective management of a firearm injury with multiple intestinal perforation in a COVID 19 positive patient: a rare case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;77:5–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.10.077.

- Rojo M, Cano-Valderrama O, Picazo S, et al. Gastrointestinal perforation after treatment with tocilizumab: an unexpected consequence of COVID-19 pandemic. Am Surg. 2020;86(6):565–566. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0003134820926481.

- Vikse J, Henry BM. Tocilizumab in COVID-19: beware the risk of intestinal perforation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(1):106009. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106009.

- Gonzálvez Guardiola P, Díez Ares JÁ, Peris Tomás N, Sebastián Tomás JC, Navarro Martínez S. Intestinal perforation in patient with COVID-19 infection treated with tocilizumab and corticosteroids. Report of a clinical case. Cir Esp. 2020;S0009-739X(20)30167-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ciresp.2020.04.030.

- Plummer MP, Blaser AR, Deane AM. Stress ulceration: prevalence, pathology and association with adverse outcomes. Crit Care. 2014;18(2):213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/cc13780.

- Pan Y, Zhang D, Yang P, Poon LLM, Wang Q. Viral load of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):411–412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30113-4.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203(2):631–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1570.

- Tian Y, Rong L, Nian W, He Y. Review article: gastrointestinal features in COVID-19 and the possibility of faecal transmission. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51(9):843–851. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.15731.

- Wang J, Li Q, Yin Y, et al. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2063. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02063.

- Laforge M, Elbim C, Frère C, et al. Tissue damage from neutrophil-induced oxidative stress in COVID-19. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(9):515–516. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-020-0407-1.

- Middleton EA, He X-Y, Denorme F, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(10):1169–1179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2020007008.

- Kong M, Zhang H, Cao X, Mao X, Lu Z. Higher level of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte is associated with severe COVID-19. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148:e139–e139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268820001557.

- Barnes BJ, Adrover JM, Baxter-Stoltzfus A, et al. Targeting potential drivers of COVID-19: neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2020;217(6):e20200652. doi:https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20200652.

- Mönkemüller K, Fry L, Rickes S. COVID-19, coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 and the small bowel. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2020;112(5):383–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.17235/reed.2020.7137/2020.

- Wu C, Zheng M, Yang Y, et al. Furin: a potential therapeutic target for COVID-19. iScience. 2020;23(10):101642. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2020.101642.