The scientific, academic, and medical application of “six degrees of separation” often leads to the stunning revelation that most of the world, even nonmedical, is no more than three degrees of separation away from the impactful legacy of Dr. William C. Roberts; stunningly, his influence is often even closer.

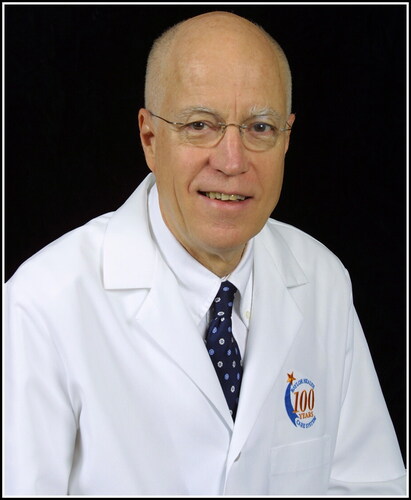

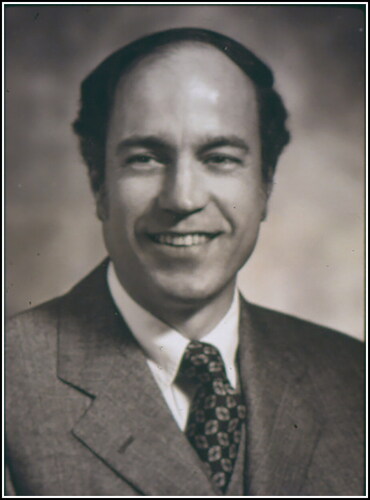

William C. Roberts, MD, Master of the American College of Cardiology—“Bill” as his friends and colleagues called him, or simply “Dad” to his children—was the premier cardiovascular pathologist in the world during his lifetime, receiving the American College of Cardiology Lifetime Achievement Award in 2016, among numerous other awards. Concomitantly with his service as editor in chief of The American Journal of Cardiology for 40 years (1982–2022) he served nearly three decades (1993–2022) as the editor in chief of Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. He passed on the editorial torch in January 2023, remaining a fountain of perspective given his experience. The Good Lord called him home on June 15, 2023, at the age of 90. Dr Roberts was a “phenomenon” and his accomplishments may never be duplicated. His more than 1700 academic articles and 31 books are only the tip of the iceberg of his contributions.

Born in Atlanta on September 11, 1932, he grew up and attended high school in Georgia. Even at 90, he could be readily identified by the soft and soothing cadence of his speech, which readily belied the foundational impact of his childhood in Georgia. Nevertheless, he got to Texas as soon as he could, adopting two home states. He graduated from Southern Methodist University in Dallas in 1954 and from Emory University School of Medicine in 1958. He finished his internship at Boston City Hospital, a 3-year anatomic pathology residency at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), 1 year as assistant resident on the Osler Medicine Service at Johns Hopkins Hospital, and a year of cardiology fellowship at the National Heart Institute in 1964. He then focused on cardiovascular pathology as head of the Pathology Branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute for 30 years. There he trained numerous fellows and influenced the leaders of cardiology in their concepts of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

In 1993, he began his second career at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas as executive director of the Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute (now known as the Baylor Scott & White Heart and Vascular Institute), where he served as cardiovascular pathologist, dean of the A. Webb Roberts Center for Continuing Medical Education, and editor in chief of Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings and led its transformation into the flagship system journal for Baylor Scott & White Health, the largest not-for-profit healthcare system in the state of Texas. As one walks through the halls of Baylor Scott & White Heart and Vascular Hospital, a series of 40 drawings of unique first-described cardiovascular anomalies and aortic pathologies give evidence to the extraordinary practice that Bill Roberts developed in his years of lovingly dissecting and cataloging the life-threatening conditions of the cardiovascular system.

There is only one way to truly describe Bill Roberts. He was a southern gentleman and considered everyone to be his friend. Everyone who has met him, even for a short time, will confirm that description. Everyone touched by Bill’s influence had unique stories. I (JWF) remember when I got the call to come to his house to be interviewed for Baylor Proceedings how humbled I was, sitting in his kitchen, when he started asking me about my life. He wanted to know what I thought, felt, valued, and regretted. I truly loved spending time with him. When he came to discuss the next stage of the Baylor Proceedings, as we transitioned leadership to a new editorial team, it was apparent that he loved this journal. He had poured his life into it. We can only hope to have the readers understand how important he was to the Proceedings and how much he invested himself in it.

During his tenure he interviewed at least 125 clinicians, medical scientists, administrators, and guest lecturers to produce their oral history as part of the Baylor Proceedings legacy. Fortunately, we have an interview of William C. Roberts himself obtained by Bruce Fye, MD, in 2007. We are republishing it in the Proceedings to help us remember Bill Roberts as he was.

His legacy endures.

—James W. Fleshman, MD, and Robert L. Gottlieb, MD, PhD

William Clifford Roberts, MD: an interview by Wallace Bruce Fye, MD

William C. Roberts, MD,a and W. Bruce Fye, MDb

aBaylor Heart and Vascular Institute, Dallas, Texas USA;

bMayo Clinic Center for the History of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota USA

Bill Roberts () was born in Atlanta, Georgia, on September 11, 1932, and he grew up there. In 1954, Bill graduated from Southern Methodist University (SMU) and in 1958, from Emory University School of Medicine. His internship was in internal medicine at the Boston City Hospital. After a 3-year residency in anatomic pathology at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland, he was an assistant resident on the Osler Medical Service at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore for a year and then a fellow in cardiology at the National Heart Institute in Bethesda for a year. From July 1964 until March 1993 he headed the Pathology Section or Branch of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. He has published just over 1400 articles, authored or edited 24 books, and lectured in >2000 cities throughout the world. For 33 years, Dr. Roberts has been program director of the Williamsburg Conference on Heart Disease, held every December in Williamsburg, Virginia. He has contributed information on many cardiovascular conditions. Since March 1993, he has been executive director of the Baylor Heart and Vascular Institute of Baylor University Medical Center (BUMC) in Dallas, Texas. Since 1994 he has been the editor in chief of BUMC Proceedings and dean of the A. Webb Roberts Center for Continuing Medical Education at Baylor Health Care System. He has been the editor in chief of The American Journal of Cardiology since June 1982 (25 years).

He has received several honors: the Gifted Teacher Award of the American College of Cardiology in 1978; the College Medalist Award of the American College of Chest Physicians in 1983; the Richard and Hilda Rosenthal Foundation Award from the Council of Cardiology of the American Heart Association in 1984; the Public Health Service Commendation Medal in 1979; the Distinguished Achievement Award of the Society of Cardiovascular Pathology in 1994; an honorary doctor of science degree from Far Eastern University, Manila, Philippines, in 1995; the Emory Medical Alumni Association’s Distinguished Medical Achievement Award in 1984; the Distinguished Alumni Award from Southern Methodist University in 1996; and the designation of master of the American College of Cardiology in 2004. Bill was married to Frances Carey Roberts for 36 years, and they are the proud parents of 4 offspring and 11 grandchildren.

Bill Roberts is the most prolific oral historian of cardiology in history! Over the past 11 years he has recorded and published more than 125 oral histories of clinicians, surgeons, and medical scientists. These published records are of interest today because they provide unique insight into the lives and careers of a broad range of contributors to the science and practice of medicine and surgery. As a medical historian and biographer, I know how difficult it is to select specific individuals to interview or to write about.

It is unnecessary to tell readers of this journal that time is the main challenge when it comes to recording oral histories. This is the main reason there are far fewer of them than there should be. Fortunately, Bill Roberts, one of the busiest people I know, has taken the time to document some of our medical history. His unique interviewing style captures personal anecdotes that bring his subjects to life. The abridged bibliographies published with the interviews are useful because they reflect the author’s own perception of his or her most significant publications. Having known Bill for more than 30 years and having admired his dedication to medicine, I thought it was important to fill one palpable gap in the oral history series he initiated. Initially, he was reluctant to grant my request to interview him because he edits the journal. I pushed the notion and, happily, he agreed. I think you will enjoy learning about Bill’s career and his many contributions.

Wallace Bruce Fye, MD (hereafter, Fye): Bill, you were born in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1932. Your father, Stewart Ralph Roberts, was 54 when you were born, and he died when you were 8 years old. Despite that, he had a profound influence on you. Talk a little bit about your childhood, your father, and your mother.

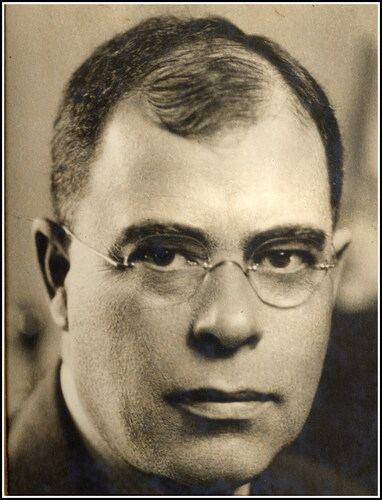

William Clifford Roberts, MD (hereafter, Roberts): Yes, he did have an influence on me. My father was born in 1878, 13 years after the end of the Civil War, and he grew up in Oxford, Georgia, about 20 miles from Atlanta (). He knew many Confederate veterans, many of whom had lost an arm or a leg. He felt very close to his Southern heritage and became a student of the Civil War. Many houses in Oxford, Georgia, were burned by Sherman. He grew up when the Civil War was a strong and influential memory. He graduated from the Atlanta School of Physicians and Surgeons in 1900 and then returned home to Oxford to attend Emory College, from which he graduated in 1902. He was first in his class and its valedictorian. Thus, he received his medical degree before he received his college degree. There were no physicians in his extended family in 1902.

Fye: It is important to recognize that most students who got medical degrees at that time never got college degrees.

Roberts: That’s true. In 1904, he received a master’s degree from the University of Chicago. His master’s thesis concerned a neurologic problem. He then returned to Oxford for a brief period before settling in Atlanta to practice internal medicine. That was 1905. I assume that he started teaching at the medical school right away. His income, however, always came entirely from his practice. In 1916, the Atlanta School of Physicians and Surgeons merged with Emory University, which had moved its main campus from Oxford to Atlanta, so the medical school became the Emory University School of Medicine. He was immediately designated professor of clinical medicine, and he taught medical students and houseofficers until his death in 1941. His teaching was at both Grady Memorial Hospital and at Emory University Hospital, which opened in 1920. During those years, he wrote a good bit. He published 105 articles and, with the exception of a few in the 1930s, all were single authored. In the 1930s with the chairman of the pathology department at Emory, Roy R. Kracke, he wrote a series of articles on agranulocytosis that apparently were relatively important scientifically.

My father married his first wife in 1905, and they never had children. My mother, Ruby Viola Holbrook, his second wife, told me that the first wife was quite “a social type” and used to spend winters in Florida, so I assume it was not a very close marriage. I made a mistake in not trying to meet her.

The first son, Stewart Ralph Roberts, Jr., was born on my father’s 53rd birthday, October 2, 1931. That was almost certainly, according to my mother, the happiest day of his life. I, the second son, was born just 11 months later (September 11, 1932). The third son, Ross Holbrook, was born May 26, 1935. Unfortunately, this last son was severely mentally retarded, maybe from a birth injury, but according to my mother, my father refused to recognize it for some time. When Ross was 5 years old, he was placed in a private institution for those children and, after my father died, in a public institution. My mother indicated to me that sending him away from home was the hardest decision she ever had to make. Ross died on July 20, 1960, when he was 26 years old.

My father had a bad heart attack in 1937 at age 57. At that time, a patient with acute myocardial infarction stayed in the hospital for a month and then stayed home for the next 11 months. (His partners paid him $500 a month during the year he was away from work.) That was the therapy for acute myocardial infarction at the time. He had been president of the American Heart Association in 1933, so he knew how to treat the condition. For his remaining 4 years he was in heart failure (ischemic cardiomyopathy). There were few drugs available then for heart failure: digitalis, aminophylline, and mercurial diuretics. The heart failure apparently exhausted him. As soon as he got home from work he went to bed. I think my mother kept my brother and me from him during his last years so he could rest.

Fye: Because you were young boys and your father obviously was just barely making it through the day.

Roberts: Exactly. According to my mother, my father had some prominent patients in other cities, and he would take the train periodically to those cities to see them. He took my brother on several of those trips. He never took me because I guess I was nearly a year younger. As a consequence, my brother remembers more about my father than I do. (My brother also has a better memory than I do, and that too may have been a factor.) I have pumped my brother for some of his memories. At any rate, I grew up with the image that my father was a very prominent man, and that had a tremendous impact on me.

In 1935, my father moved the family from his Ponce de Leon home located about 2 miles from Emory Hospital to a 118-acre farm about 12 miles from Atlanta. He believed that his lifespan would be shortened by his high blood pressure, and he thought it would be good for his sons to grow up on a farm with animals. My brother and I milked cows. My mother sold the milk to Emory Hospital. Although my brother disagrees with me, I believe the move to the farm was probably not wise because it bled my parents financially and our house at the farm burned to the ground several months after my father died. We then moved to a smaller house in Atlanta (16 Woodcrest Avenue), where I grew up.

Many things my father had saved for my brother and me (watches, Phi Beta Kappa chain, books, etc.) were lost in the house fire. Some neighbors saw the flames and saved a few pieces of furniture and some books. My mother gave the medical books that were saved to the medical school library at Emory. When I was a medical student at Emory from 1954 to 1958, I found some of my father’s reprints in the library’s drawers and was given permission to take a few of them. I also went to Index Medicus and made a list of his publications and got them bound together. My son, Charles Stewart, later referred to the two-volume set of collected reprints to write a book about my father, and he also found several reprints that I had missed.Citation1 I have read most of my father’s publications, and they have been a great inspiration to me. His collected reprints are my prized possession!

In 1914, my father wrote a book on pellagra, which was widespread in the South at that time.Citation2 The disease was characterized by the 4 D’s: dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia, and death. My father apparently saw many patients who had pellagra, including some wealthy ones. How he got so interested in that condition is unclear to me. He studied the problem in Italy in 1911 because it was apparently even more prevalent there than in the USA. His book came out in 1914, and Goldberger, who later proved that pellagra was due to a dietary deficiency, started his seminal work that same year. My father gave me a copy of his pellagra book a year before he died, and he inscribed in it the following: “To my second son, William Clifford Roberts, at seven years and 4 months. I hope he may love books, read and write much.” Of course, I cherish this inscription from my father and have tried to live up to it.

Later, my father became interested in heart disease and appears to have had the first electrocardiographic machine in the South. He wrote several papers on angina pectoris. Heart disease became his major medical interest. Paul Dudley White and some other prominent early cardiologists were friends. In 1926 my father, along with several others, was involved in establishing the American Heart Association. Early on he was on the editorial board of the American Heart Journal, the official journal of the American Heart Association until 1951 when Circulation replaced it.

My mother was born in 1903. She started working for my father as his secretary in 1925. My father’s office was on Juniper Street at 5th Street, and my mother lived on 10th Street so she would walk to work. She was usually a very cheerful person. She went to Commercial High School and learned to type and to take dictation well. She did not have the money to go to college, although she would have loved to have gone to Agnes Scott College (near Atlanta) and majored in English. My mother also served as a nurse in the rooms where my father examined patients. He hospitalized his patients at Emory Hospital. He began his day seeing his patients at the hospital, and then he would come to his office on Juniper Street.

During that period, my future mother and my future father became close. My father divorced his first wife in 1928. For a while after the divorce my father didn’t ask my mother to marry him. As a consequence, she became annoyed and moved to New York City and got a job there. After a few months he came to New York and they got married on December 10, 1929, just 2 months after the stock market had crashed. Their wedding was announced on the front page of the Atlanta Journal and Atlanta Constitution because of my father’s prominence in Atlanta. In early 1929, my father had borrowed $25,000 from the bank to “settle” his alimony. In 1929, that was a lot of money, and he borrowed the whole amount and sunk it into the stock market. When the market crashed, the value of his investments was essentially gone. He and my mother were married 11 years (my father died in April 1941), and during that entire period they were in debt. My mother paid off his debt in 1945. She went to work shortly after he died. My mother referred to my father all of her life as “Dr. Roberts.” She never called him Stewart.

My mother grew up in a family of 11 full siblings and 3 half siblings. Of the 11 full siblings, 10 were girls, and of the 3 half siblings, 2 were girls. Her father died at age 45, shortly before the eleventh child was born. He built furniture for the Pullman railroad cars. My mother told me that my father thought her father and three or four of her sisters had tuberculosis. I asked my mother once what she remembered about her father. She recalled one episode: she was looking out a window of the house and spotted him walking home from work, and she said, “Here comes Daddy down the street,” and they all went out to greet him.

In our new house in Atlanta beginning in late 1941 my brother and I each had a room of our own. My mother worked every day. After my father died, she started out as a secretary for an insurance company and was progressing along and then decided to form her own business, Medical Placement and Mailing Service, which she sold about 1975. She was a very hard worker. As far as I can remember, she took one vacation from 1941 until she died in 1994.

Fye: I read that interview with your mother. I thought that was fascinating.

Roberts: She got secretaries and nurses jobs in physicians’ offices and she placed a few physicians with insurance companies. The mailing service consisted mainly of sending out reprints of articles physicians had written and brochures for upcoming medical meetings. I fairly frequently ran the mailing machines. Virtually every night, my mother typed addresses of physicians in the South because they often changed addresses. As a consequence, she never had much free time. I always thought she would have been better off if she had stayed with the insurance company because she was just beginning to move up. She would have had an annual vacation. She had one person working with her. She sold the business in about 1975 for $75,000, and the new owner then closed it. I never quite understood why.

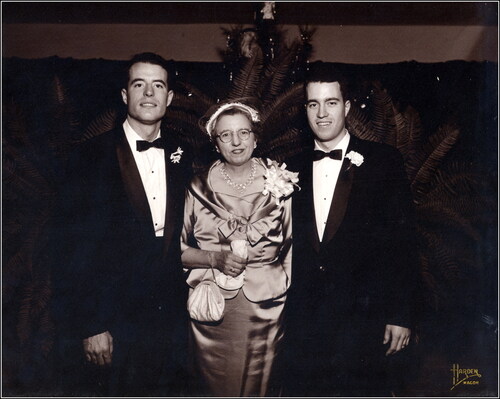

My mother was the one who brought me up. She was a very sweet lady, devoid of any mean bones, and she had a positive attitude about life and considered misfortunes a part of life and moved on quickly from there. She was certainly not worldly. She was devoted to my brother and me (). Five of her 10 full sisters and one of the two half-sisters married. Often, one or more sisters came to our house. As a consequence, I had very little contact with men. I used to be nervous around men because I rarely talked to them. I didn’t fish, I didn’t hunt, and we went on a family trip only once (to New York City and Coney Island).

Figure 3. With his mother, Ruby Viola Holbrook (age 53), and older brother, Stewart Ralph Roberts, Jr., MD (left), at Stewart’s wedding in 1957.

Fye: Where was the one boy in the 11 siblings?

Roberts: He was about midway, and he left home early.

Fye: Imagine that.

Roberts: My mother thought he was a bootlegger because he had come home during the Depression on occasion with a fancy car. He died early too. He apparently drank a little too much and rode motorcycles, so apparently he was a little wild. It is understandable. He died before I was born.

Fye: You went to public high school in Atlanta. What things were you interested in during high school? What courses did you like and what did you enjoy doing, scholastically and extracurricularly? Talk a little bit about those years.

Roberts: I wasn’t one of the brighter students in my class. I was a good boy. I did what teachers asked. After coming to Atlanta I entered the fifth grade at Spring Street Grammar School, and my brother entered the sixth grade. That was a change because I had gone to a small public school in Avendale, Georgia, now a big suburb of Atlanta. I wasn’t, I thought, quite as prepared as some of my fellow fifth graders. The sixth grade had two teachers: Ms. Adams and Mrs. Clifford. Every student wanted to be in Mrs. Clifford’s class and all of my friends were, but my brother and I were put in Ms. Adams’ class. The sixth grade was a disastrous year and was a major reason I was placed the next year in one of the lower seventh-grade classes at O’Keefe Junior High School, which is adjacent to Georgia Tech. Each of the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades had about eight different classes, numbered 11 to 18—the higher the number, the slower the students. I was placed in class 17 in the seventh grade, but by the ninth grade, I had worked my way up to class 12, so I was pleased with that. Henry Grady High School began with the tenth grade. An algebra teacher that first year in high school told me, “You are a pretty good student; just keep at it.” I got an A in algebra, and I just loved that lady.

I enjoyed school. I played a lot of sports: football, basketball, baseball, tennis, golf. This was a big high school. My class was the first of the coed classes. (Formerly, it had been Boys High School when boys from all over Atlanta went to the same high school. There were two girls’ high schools: Girls High School and Commercial High School.) I was a late grower. When I got my driver’s license at age 16, I was 65 inches tall and weighed 110 pounds! Those numbers are on my first driver’s license. I grew a good bit (to 72 inches) the next 3 years.

Fye: It is called a “growth spurt.”

Roberts: Yes. My size was not advantageous to my athletic career. My best sport, I guess, was baseball. I was a catcher and my brother was a pitcher, and we played sandlot ball. He also played on the high school team, but I did not. He was better in high school than I was, although I hit better than he did in sandlot. I played basketball in a YMCA league. I loved that. I wasn’t good enough to make any of the high school teams. Many of my friends, however, were good jocks.

I always liked the independence my mother gave Stewart and me very early on. When my brother and I got home from school after moving to Atlanta, my mother wasn’t there. She was working. By the eighth grade I had a paper route and continued it through senior high school. When I worked at my mother’s office or the YMCA, a friend, whom I paid, threw the newspapers for me. As a consequence, I always had some spending money. I had a great paper route. All the delivery boys were jealous of my route, so I wasn’t going to give it up. I could throw all the newspapers in 1 hour.

Fye: This was on a bicycle, I assume?

Roberts: Yes. I didn’t particularly like having to wake up early on Sunday mornings. Newspaper boys collected directly from customers at that time. I would knock on the customer’s door at night and get 25¢ or whatever it was. I enjoyed it. I particularly enjoyed the independence. My brother and I did our own clothes shopping from sixth grade on, as I remember. If mother had to work late, we would either fix dinner or go to the hot dog place. The freedom just fit my personality perfectly. My mother never pressed my brother or me to make A’s. We never talked about it. I tried to do as well as I could. I wasn’t a brilliant student. I became a much better student as I gained confidence with time.

I also worked at the YMCA one year in high school. I worked in the office of the director, George Abbott. He was a mentor for me and encouraged me to go to Harvard because he had come from Boston. I said, “I can’t get into Harvard.” He wrote some letters, and Harvard said, “If he goes to prep school for a year, maybe he could come up then.” I wanted to get on with it, and it took money to go to prep school. (I doubt if I could have handled Harvard at that time anyway. It was a nice thing, however, to have that said to me at that time.) I forgot exactly which colleges I applied to. I knew I wanted to go away to college.

My mother and I were very close and we usually talked after dinner, after we boys rinsed and stacked the dishes. Our dinners were pleasant. We may have discussed some of our events of the day. I do not remember ever talking about current events. It was not an intellectual table. Although my mother read a bit every evening before retiring, she didn’t talk about what she had read and, unfortunately, I was not a questioner at that time in my life. Later on, I started questioning and questioning and questioning. I think that is when I started learning. After dinner my mother and I would sit in the living room. She would talk about her business day. I loved our conversations. I got the feeling that she really liked what I had to say.

I wanted to go away to college. I knew that move would hurt my mother a bit and would really be the end of our real closeness, and I felt badly about that. At the same time, I think my mother knew that going away would be good for me. I wanted to go to a college in a city relatively comparable in size to Atlanta and also a coed school because I thought that was the real world. I applied to SMU, probably because Doak Walker and Kyle Rote, the famous football players, were there. I received an acceptance letter immediately. I had never been west of Georgia, so I thought Texas sounded good. My mother said going to SMU in Dallas would be fine. When I went to SMU, I did not know anyone there, and I loved it ().

Fye: Were you Methodist?

Roberts: Yes. I used to go to Presbyterian Sunday school at 9:00 am, and then my mother would pick me up and we would drive to St. Mark’s Methodist Church for the 11:00 am service. At the Presbyterian Church the students ran the Sunday night youth service. I gave several “sermons” at that night service. Those were the first talks I ever gave. I enjoyed it.

In my junior year in college, I roomed in the theology dormitory. There were a lot of athletes there too because the athletic dorm overflowed. One theology student there had been a counselor at a boy’s camp in Minnesota about 100 miles north of Minneapolis. He asked me if I would like to be a counselor there. They paid fairly well and my mother approved. I was the tennis instructor. It was wonderful. I was asked to give one Sunday morning sermon at the camp. I remember going out in the woods and practicing. That was a great summer.

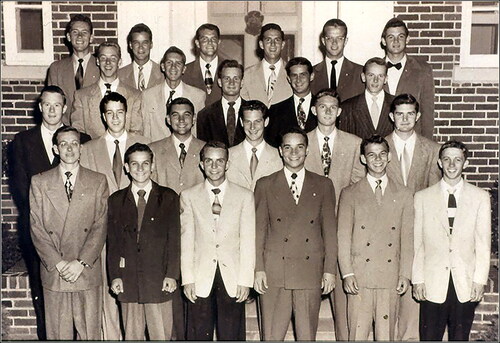

I loved college. I met a lot of people. I joined a fraternity (Phi Delta Theta) where many of the members had grown up in Dallas. As a consequence, when I came back to Dallas in 1993, I knew a number of people from college. My fraternity pledge class numbered 23 (), and probably 12 of them stayed in Dallas after graduation. I majored in English. I went to college thinking I was going to be a business student, but by my junior year I said, “No, I’ve got to get into medical school.” During my second year in college the Korean War started and several of my classmates volunteered. I thought it might be a good idea to finish college a bit early, so I went to Emory that summer, took three classes, and made three A’s. I believe those summer school marks at Emory helped me get into medical school there and, of course, my father’s reputation at Emory did not hurt.

Figure 5. Pledge class of Phi Delta Theta at SMU in 1950. Dr. Roberts is in the second row, second from the left; Dr. George Hurt is in the last row, third from the right.

Fye: Before you went to SMU, thinking you were going to go into business, did your mother ever encourage you toward medicine? What role did she play in your eventual decision to turn to a medical career, and what other influences were in that mix?

Roberts: I don’t think my mother and I ever talked about it. The only thing she knew was medicine. She had worked for my father. That was her second job. (She worked for AT&T a year or so out of high school.) She knew quite a few physicians in town through my father and through her business, of course, and we had some medical books in the house. My father’s brother, James William, was a general surgeon in Atlanta, and my mother told me a lot about his relationship with my father. One paternal first cousin, Tom Ross, was an internist who became a cardiologist and was in practice with my father before returning to his home in Macon, Georgia. And a paternal cousin, Lamar Roberts, trained with Wilder Penfield in neurosurgery in Montreal and was on the faculty at the University of Florida in Gainesville for several decades.

Fye: So medicine was sort of in the air?

Roberts: Yes. The only businessman I knew was my mother’s brother-in-law, Bill Neal, who had his own advertising agency in Atlanta with an office also in Richmond. He did quite well. I was always very impressed with him. When I was a senior in college, I heard about a job at a resort in Colorado and applied. They said, “Okay, you can have it, but we need a letter of recommendation from somebody who knows you.” Because I knew my Uncle Bill Neal had nice stationery, I asked him. He sent me a copy of the letter that said, “This is a fine boy. He works hard. He is nice, easy to get along with, he doesn’t smoke, he doesn’t curse, and he doesn’t drink alcohol.” Well, it turned out that they wanted me to be a bartender, and they then turned me down.

Fye: Isn’t that amazing.

Roberts: During my senior year in college I also applied for a job in the Idaho forests and while waiting to hear from them, I got a job in the wheat fields in the Texas Panhandle. After a couple of weeks of farm work, the Idaho job came through. I spent 2½ months before medical school working in the Idaho forests.

Fye: What were you doing there?

Roberts: I started as a Rybe bush (ribgrass) picker. It was a federal government job, and I wanted that job because there were usually forest fires there in the summer and I heard the Rybe bush pickers would be pulled off to fight the forest fires and would get overtime pay. I planned on having some good money before I started medical school. It turned out that there wasn’t a single forest fire that summer. We lived in camp tents. After a month or so I was promoted to a stringer—a fellow who strung a string for a mile, then paced 300 yards at right angles, and then brought the string back for another mile. The Rybe bush pickers worked back and forth between the strings searching for Rybe bushes and then pulling them up by their roots. The boss would hide between the strings, making sure the Rybe bush pickers did their job properly. Getting a promotion from a Rybe bush picker to a stringer was one of the best promotions I ever had.

Right after high school I quit my paper route and got a summer job as a proof chaser for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution newspaper. That job consisted of carrying advertising copy from the newspaper presses to the various advertising agencies in town. It was during the humid, hot summer, and the ink from the proofs made its way to the clothes. Thus, proof chasers were not very attractive, sweating like horses walking into the sophisticated advertising offices occupied by beautiful ladies and well-dressed men. After that summer, I decided that I would study hard in college because I did not want to be a proof chaser all my life. Nevertheless, it was a wonderful job. At college, I often spent the entire Sunday in the law library at SMU. I never felt sorry for myself for working hard again after having been a newspaper proof chaser.

Fye: It is interesting that you got back into the world of printing in a sense but obviously at a totally different level. Were there other students at SMU who were interested in medicine?

Roberts: There were several. One was George Hurt, who had a big impact on me. He had gone to Highland Park High School and grew up adjacent to SMU. From the time he entered grammar school until he graduated from medical school, he never made anything on his report card but an A, and his nickname was “Happy.” He had a photographic memory. He became a prominent urologist in Dallas. He also was a three-sport athlete in high school: football, baseball, basketball—first team on all three. Another was Malcolm Bowers. He was also from Dallas and also made all A’s. He came to SMU on a football scholarship. He too had been a three-sport athlete at Highland Park High School but, in contrast to George Hurt, he studied all the time. His focus was magnificent. He later became professor of psychiatry at Yale. Another fellow in my class, also from Dallas, was David Weakley. When spring came I didn’t see him and wondered where he was. It turned out he was a champion Southwest Conference low hurdler and high hurdler for 4 years and was training in the spring. I had known him for about 6 months. He never mentioned to me that he was on the track team. He also made all A’s. He went to medical school at Columbia University and became a prominent ophthalmologist in Dallas. Another friend, Don Alexander, threw a paper route all through college. He got up at 5:00 am daily. He also had been a star quarterback at Highland Park High School. He too made mostly A’s. He trained in otolaryngology at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and returned to Southwestern as professor of surgery and head of otolaryngology. Larry Embree left SMU after 3 years to go to the University of Arkansas School of Medicine. He graduated first in his medical school class and did an internship and residency in internal medicine at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston and a fellowship in neurology with Raymond Adams at The Massachusetts General Hospital. He later went to Shreveport, Louisiana, as chief of neurology at the new medical school there. SMU has some high-quality students!

Fye: How did you decide to go back to Emory? Who were some of the people that influenced that decision?

Roberts: It was entirely me. I thought it was selfish of me to be gone for 4 years when my mother was at home by herself in Atlanta. If I could get into Emory medical school, I thought that was clearly the thing to do. Fortunately, I did. I was glad to get that letter of acceptance. My father had gone to Emory, and there is a bench in front of Emory Hospital with his name—Stewart R. Roberts, MD—on it. Also, his picture hangs in the hallway across from the dean’s office at Emory School of Medicine. Many Robertses had gone to Emory.Citation3 The only other school I applied to was Tulane. It wasn’t such a big deal getting into medical school in 1954. I have always thanked my lucky stars for having gotten in. As Robert Frost said, “It has made all the difference!”

Fye: What was it like when you got started in medical school? What did you like and dislike about it?

Roberts: I loved it. I was so grateful to be there. I liked anatomy very much. We had one human body and four medical students on it. I did all the dissecting because my three colleagues wanted me to and I wanted to. It turned out that all three of the nondissectors became surgeons. I enjoyed the dissecting. I thought I was going to be a surgeon. I always felt that I was good with my hands and I liked that. Biochemistry, in contrast, was not easy for me. The chemical concepts were difficult for me.

Fye: There was memorization in anatomy, but at least there is sort of a visual connection to it and a certain logic.

Roberts: Yes. Anatomy made sense to me and it was sort of easy. I had to study hard to learn all those terms and names. I think I got that from my mother. I never minded having to put in a lot of hours. I realized I wasn’t brilliant. In class I wouldn’t always understand what the teacher was saying, but I always took good notes and tried to figure it out later. In contrast, George Hurt would walk out of the class having grasped all of the concepts. I was envious of his abilities.

Fye: I am with you 100%.

Roberts: When I came home after my junior year in college, my mother had a little party for a friend from college, Larry Embree, and me. My cousin, Dexter Allen, brought a young lady, Carey Cansler, who was very attractive, and I talked to her some that night. I called Dexter the next day and said, “Dexter, are you dating this lady regularly or do you intend to? If not, would you mind if I called her up?” He said, “No, I am not dating her; go ahead.” I not only asked her out but asked that she fix up my friend. During my freshman year in medical school (while she was attending Agnes Scott College in Decatur, Georgia, near her home) we dated regularly. It was a little strain that freshman year trying to keep up with all the new information and dating Carey regularly. She was the first girl I had ever gone “steady” with. We got married after that first year in medical school. The second year in medical school was great. I enjoyed pathology, never intending or even considering later doing a residency in it. I loved the two clinical years. I had a very hard time deciding whether to go into surgery or into medicine.

In the two clinical years, my medical school class of 66 students was divided into groups of eight. I loved surgery, and none of the other seven in my group liked surgery at all. As a consequence, I scrubbed on most of their cases as well as mine. The surgery houseofficers at Grady Memorial Hospital were sure that I was going into surgery, but I had this pull from my father’s being an internist and from some impressive internists, particularly Willis Hurst, at the medical school, even though surgery was more natural for me than was internal medicine. Later, I realized that to be a good internist you really had to be good. I thought one could be a good surgeon just by being technically good, while internal medicine was a greater challenge. During my junior year in medical school I was on Willis Hurst’s service when, at age 36, he was offered the chairmanship of the Department of Medicine at Emory. He sort of opened up to me at that time, telling me the good and the bad about being chairman of a department. He was and still is a fantastic teacher. He talked to me those 3 weeks. Willis Hurst, along with my father’s influence, switched my interest from surgery to medicine, and I decided to intern in medicine.

The first day of my junior year in medical school when starting on ob-gyn, I got on the elevator and there was Lyle Stone, who was a year ahead of me. I said, “Lyle, what did you do this summer?” He said, “I had an externship at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, DC.” I said, “How did you get that job?” He got off at the next floor, and I followed him. He told me how he had gotten that job. I applied that night and lo and behold, I got it. I had an externship at Emory Hospital during my junior year and was supposed to go back, but Emory let me go when I told them about the offer from Walter Reed.

Carey and I went to Washington, DC, and rented a room in a house near Georgia Avenue. I worked at Walter Reed Hospital for 2½ months. When I arrived they said, “What service do you want to be on?” I asked, “What are my choices?” They mentioned thoracic surgery. I said “I’ll take it,” so I spent 2½ months on the thoracic surgery service. The chief was Hugh Blake. Blake and I became friends, and he would go out to NIH periodically to see Glenn Morrow, who was chief of the Surgery Branch (clinic of surgery as he called it) in the National Heart Institute. Hugh Blake would say, “Come on, boy,” and I would go out there with him. I had never heard of NIH or the National Heart Institute. I learned that one could fulfill the 2-year mandatory military obligation at NIH. I knew that after my internship I would have to go into the service, so I applied for the clinical associateship program in the National Heart Institute. I was interviewed by Robert Berliner, its scientific director, and I didn’t get the job. There were only six clinical associate positions in the heart institute, and probably 500 applied.

I found out that one could apply for a residency in pathology at NIH and that too would fulfill the military obligation. I figured if I could get the pathology residency job, I could apply 1 of the 2 years of that residency to either a surgery residency or to a medicine residency program. I applied for the position and was the first alternate. I inquired, “Have any alternates been chosen previously?” They said, “No, never in the past,” but about 3 days later some fellow pulled out. There were only two positions, and I slipped into one of them.

Fye: That was during your senior year of medical school?

Roberts: No. That was during my medical internship.

Fye: Your internship was in Boston?

Roberts: Yes. I interned in medicine at the Boston City Hospital. The chief of surgery at Grady thought I was coming there in surgery, and maybe I should have. I enjoyed Boston City Hospital and I enjoyed Boston, but I don’t think I learned as much as I would have if I had stayed at Grady Memorial Hospital. I was a bit disappointed in that internship. I felt very prepared compared with the Harvard or Boston University or Tufts University housestaff. I don’t think they had gotten as much practical training as we had gotten at Grady. I felt pretty confident on the wards, but intellectually there just wasn’t enough time to learn quite as much as I thought I should have. (Back in 1958 medical students applied for their internships during their fourth year.)

Fye: Young trainees today have no clue about how different it was 40 years ago. When you talked about the intellectual piece on surgery, I was thinking that pathology is an intellectual discipline—a subdiscipline of surgery because you look at organs, thinking about why they didn’t work right or what clues were there. There was a lot more to differential diagnosis and the whole clinicopathologic conference phenomenon in those days.

Roberts: The last thing I ever thought about going into was pathology, but I loved the pathology residency at NIH. There were six residents and it was great. We did autopsies and surgicals. I never did clinical pathology. The anatomic pathology department at NIH at the time was in the National Cancer Institute. As a consequence, all the staff in the pathology department were interested in cancer, but yet the autopsies from all of the various institutes were done there in the Department of Pathology in the National Cancer Institute.

I was interested in heart disease, and the second most common autopsy was from the National Heart Institute. None of the pathologists liked doing autopsies from the heart institute because Glenn Morrow would give them a hard time at the mortality and morbidity conference. I liked doing the heart cases, so within a month or so I was the “heart pathologist.” Well, I didn’t know anything about it, but it forced me to read and read and read. At the first or second mortality and morbidity conference, I presented the morphologic features of a case and said, “The patient had a congenitally bicuspid aortic valve.” This statement startled Glenn Morrow, who said, “What?” I said, “Come see.” He did and said, “I think you are right.” That was my breaking in with Glenn Morrow! During the second year I decided to stay for a third year so that I would be board qualified in anatomic pathology. During that second and third year I attended Gene Braunwald’s daily ward rounds. It was a fantastic experience.

Fye: I noticed he was the first author on your first paper.

Roberts: Yes, he was. He is the best. I decided during that third year I should go into surgery because that would allow me to see people and also use my hands. I applied to Duke. (This was before David Sabiston got there.) They said, “Well, you will have to start as an intern.” I said, “I bet in 2 or 3 months you won’t be able to tell the difference between me and those who interned in surgery.” These discussions went on for a while. In the meantime, Glenn Morrow offered me a job to start a pathology section in the Surgery Branch of the National Heart Institute ().

I told Glenn to let me think about the offer. After a day or so I came back to him and said yes—if I would be allowed to do a year of residency in medicine elsewhere and then come back to do a year of cardiology in the heart institute. He said that he would have to clear that request with Robert Berliner. In the interim I got an okay from Duke to start in surgery as a first-year resident. The Duke program was 5 or 6 years at the time, the pay was minimal, and I had no money. I would have to borrow money, and I already had three kids. In contrast, NIH would pay me a commissioned officer’s salary during the 1-year medical residency and during the 1-year cardiology fellowship after returning to NIH. The decision was easy.

Fye: This was the time when cardiology was exploding with new stuff: artificial valves, pacemakers, etc.

Roberts: You only had to have 1 year of cardiology training to be a board-certified cardiologist at the time.

Fye: You were killing so many birds with one stone it was hard to keep track. Now was Gene Braunwald part of the reason you went to Hopkins? How did you make that decision? Was it proximity and opportunity, or how did that work?

Roberts: Actually, I applied to Grady where J. Willis Hurst was chief, and I didn’t hear from him. I knew that Gene had taken a year at Hopkins so I sent in an application to A. McGeehee Harvey, chairman of the Department of Medicine at Hopkins. My wife’s parents lived in Cincinnati at the time. I guess the application arrived in Dr. Harvey’s hands on Thursday. We drove to Cincinnati on Friday and soon after arriving there I got a call from Dr. Harvey offering me a job as assistant resident on the Osler Medical Service. It took me about a second to say yes.

Fye: Amazing.

Roberts: And what happened? A. McGeehee Harvey had called Gene Braunwald and asked, “What kind of guy is Roberts?” Apparently Gene said something nice about me and that was it. About a month later Willis Hurst called me and I said, “I already have a job.”

Fye: Unbelievable. Even at that time, Braunwald and Hurst were either superstars or on a projectory to being superstars, but no one could have ever imagined how successful both would be.

Roberts: Gene Braunwald shifted the gears of cardiology. Nobody had ever been as productive a researcher as he. He was brilliant and also loaded with common sense. The thing I liked about him was that he didn’t care where a new idea came from: from a basic research lab, clinical observation, autopsy table, etc. His only question was: “Is it new and is it correct?” I was in the pathology department of the National Cancer Institute doing projects with Gene Braunwald and Glenn Morrow. Although Gene was a tough taskmaster, the people who worked under him had great respect for him. Being in another institute, I was a bonus or perk to Gene. I have not encountered Gene’s equal since.

Fye: All of this is amazing serendipity. As the opportunities arose, you made decisions that affected your future career in a big way.

Roberts: I sure did. Things just sort of fell into place, and it seemed like the natural thing to do. My first year in the National Heart Institute consisted of 8 months as a surgical associate with Glenn Morrow and 4 months in the cardiac catheterization laboratory with Gene Braunwald’s associates. Thus, I never officially had typical cardiology training. I got to do a lot of cardiac catheterizations, and I scrubbed on a lot of heart operations. That year was splendid from every possible aspect.

Fye: When you were working in the cath lab coronary angiograms were not done. Most patients had either valvular or congenital heart disease, which is very different from today’s cardiac catheterization patients. Talk a little bit about that.

Roberts: That’s right. No coronary angiograms were done then. Some people in the cath lab really had to think. I really didn’t do much thinking when I was in the cath lab; I was learning the procedures. Dean Mason and John Ross had to figure out complex congenital heart diseases or multivalve heart disease or the “new” disease called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. I never did a transseptal left-sided heart catheterization, but they did plenty of them. Dean Mason often would spend all day in the cath lab. Those guys made enormous contributions. We would give amyl nitrate by inhalation to the patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. That stuff, which smelled awful, would shoot the left ventricular systolic pressure way up. The cath lab was a very intellectual place then. We did direct left ventricular punctures to obtain that chamber’s pressures in patients with aortic valve stenosis and with the arterial needle would get the systemic arterial pressure. It was fantastic.

Fye: It must have been very exciting to be right in the middle of that activity when the NIH was exploding. Money was flowing freely into NIH. A lot of very energetic young investigators were starting these things. You started the cardiac pathology program there.

Roberts: Yes. It was great. Gene Braunwald had his pick of anybody he wanted in the country. He looked for particular talents. Glenn Morrow in the Surgery Branch also had his pick of the top surgical trainees in the country. The surgical associates usually had had a year of internship and a year of residency before they would work with Glenn Morrow. His second-year boys would do the thoracotomy or median sternotomy incisions, and the first-year surgical associate, which is what I was, would assist. On my first day, I assisted with the opening and closing. Glenn Morrow would come in, do the main operation after establishing cardiopulmonary bypass, and then leave. There were only three of us at the operating table. Everyone did something. Occasionally, Gene Braunwald would come into the operating room. It was very exciting. Braunwald was an enthusiastic, intellectually curious, and hardworking leader. He inspired everyone to work hard and efficiently.

Fye: He still is.

Roberts: That’s right. Glenn Morrow was different. Glenn was very smart, a good surgeon, and an excellent writer. When Glenn Morrow left NIH in the evenings, his work stayed at NIH. But Glenn would come in on Saturdays. We often wrote manuscripts on Saturdays. If you wrote a paper with Gene, you would usually go over to his house. Gene met with somebody from his lab almost nightly, and the day of the week did not matter a great deal.

Fye: You quickly became one of the most prolific medical writers of all times. Obviously being in Gene Braunwald’s orbit was an energizing influence, as you have described, but tell me about your passion for writing. Pathology lends itself to images. Talk a little bit about the quality of the pathology images that came out of the NIH that complemented your words.

Roberts: Yes, photography became a big part of my existence at NIH. There was a fellow named Kinsey Edwards to whom I owe a tremendous amount. Kinsey didn’t have much education. When he first came to NIH he worked in the grass-cutting crew. He learned of an open position as a photographer in the pathology department. Kinsey said, “I can learn that.” He took a course in photography at the YMCA and became a superb photographer. Initially, I worked with him 2 mornings a week, about 6 hours a week. As a consequence, Kinsey and I became very close. I tried to never miss those 3-hour sessions.

I spent a lot of time studying how to demonstrate particular cardiovascular diseases. I finally learned never to open a heart when it was fresh. I placed it in its own container of formaldehyde until it was fixed. I learned that we die in ventricular systole and, therefore, these cavities at necropsy correspond to their sizes in peak systole during life. I spent a good bit of time trying to illustrate hearts properly. That is why I say my hands really paid tremendous dividends for me through the years. Although I didn’t go into surgery I needed my hands. Good photography paid handsomely for me. Good photographs are possible only if the heart is opened properly.

Fye: You clearly figured out how to get just the right cuts for photographs that made sense to your readers, the people who learn from you.

Roberts: Thanks. I figured out early that opening hearts according to flow of blood, the way they are opened in most hospitals, is rarely useful. It is like taking a tire and cutting it transversely and then stepping on both ends of the tire, and then trying to convince others that the flattened piece of rubber is a tire! That is not people’s image of a tire. I have always tried to keep the heart as it was during life. That is my goal. There is no single way to open a heart. It depends on the type of cardiac condition present. I finally got my own photographer for my lab in the National Heart Institute, and that made a big difference in my life. Although I always opened the specimens, I didn’t have to spend so much time with the photographer after a while. The man who gave me everything for my lab in the heart institute—full-time positions, square footage for laboratory, offices, etc.—was the institute’s scientific director, Robert Berliner, who had earlier turned me down as a clinical associate in the institute.

Fye: He was a renal physiologist?

Roberts: Yes. He gave me all my positions early on. I never got an additional one, never needed an additional one.

Fye: But he was sure a patron early on?

Roberts: I am totally indebted to him. Dean Mason and I became very close friends. Nobody worked harder than Dean Mason. If you didn’t work like a dog there you were just out of the club. Dean and I wrote a lot of papers together. It was a lot of fun. He is a great guy; we were born 2 days apart. Gene Braunwald and Dean Mason have the best minds I have encountered.

Fye: As you know, I am now writing a history of cardiology at the Mayo Clinic. I see that you were coauthor with Jim DuShane on a couple of monographs. Talk a little about Jesse Edwards. What other influences were in cardiac pathology before you? Did you have any connection with the Mayo group?

Roberts: The best in cardiac pathology in my view was Jesse Edwards, who hailed from Boston. His brother was a vascular surgeon at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Jesse was a top student at Tufts Medical School. He came to the National Cancer Institute’s laboratory of pathology about 2 years before the beginning of World War II. He wrote a lot of manuscripts in cancer research. In the war he was in the European sector and met Howard Burchell, who convinced Edwards to come to the Mayo Clinic after the war. Their early cardiac group there included Howard Burchell, James DuShane, Jesse Edwards, John Kirklin, and Earl Wood. Early on Jesse studied the Mayo Clinic’s collection of congenital hearts and wrote extensively.

Jesse Edwards knew how to illustrate. He knew what a surgeon needed to know from the operative incision approach. He knew a great deal of cardiovascular physiology. Jesse was well rounded in the clinical aspects of heart disease. He had a wonderful eye. He was a good histologist, a good gross anatomist, a good general pathologist, and a good surgical pathologist. He worked efficiently and effectively, and he wrote clearly. Jesse taught me much via his writings. I never trained with him, but I studied most of his publications. Jesse Edwards was the first real clinicopathologic correlator. He sensed early on what clinicians seeing patients with heart disease needed to know. His publications included pieces on most of the cardiovascular diseases. He gave his fellows more credit than they deserved. He was extremely generous with his colleagues. He is also a great guy. Jesse Edwards has elegance.

I am comfortable in the heart, vessels, and lungs. Jess, I think, was comfortable with most or all organ systems. People ask me periodically, “What are you?” and I say, “I am a student of heart disease.” I am much better in taking care of patients with heart disease than I am reading a breast biopsy. I feel comfortable in cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, but I don’t feel comfortable anymore in cancer of the colon or skin, etc.

Fye: In the late 19th century there was this notion of physiological pathology. The surgeons who started heart surgery could be characterized as physiological surgeons because they had to understand the various pressures in the heart and vascular system. The heart is obviously a living dynamic thing. Give your own sense of this because the heart is not a static structure. Somebody who works on brain pathology doesn’t deal with the same issues that you deal with as a cardiac pathologist.

Roberts: I understand that Harvey Cushing made the statement, “What we need are surgeons without hands.” I think what he meant by that is that we need brighter thinkers in surgery and maybe a little better operative judgment. I disagree. I have no respect for surgeons who are not technically good. If somebody is going to touch my body, I want them to be technically superb, and all surgeons are not technically superb. Some are clearly better than others. I can tell looking at an operatively excised cardiac valve whether the surgeon is technically good or not. At NIH we had three surgeons. I could just look at the jar and know who did the operation.

Fye: Just by what came out?

Roberts: Exactly. I can do the same at BUMC. I can identify the technical quality of the surgeon by how the cardiac valve is excised. I think cardiologists need to get a better sense of that. There are some surgeons who take valves out in multiple pieces; others take them out perfectly intact. I don’t want these little fragments flying up to my brain, and I don’t think many patients do either. Anatomy and technical skill are very important, particularly in heart disease. Heart disease is mechanical. When I was in medicine I knew I couldn’t be an excellent endocrinologist or nephrologist. Both were too biochemical for me. I knew they were not my thing.

Fye: The word that comes to mind for me is “uninteresting.”

Roberts: It is easier to get a handle on heart disease. Maybe I should say something about my Hopkins experience from July 1962 to June 1963, because that was a glorious year for me in medicine and also for my family at the time. We had three kids and lived in “the compound.” My wife was quite happy there with the families of the other houseofficers. The children played in the enclosure. I loved Hopkins. I was offered a job in cardiology there by Dick Ross and in pathology by Ivan Bennett (a joint appointment). I was very flattered by that, but I had a commitment to return to NIH, and that made accepting impossible. Fortunately, as mentioned earlier, I had attended many of Braunwald’s ward rounds and also the cath conferences every Friday afternoon at NIH all those 3 years I was in anatomic pathology training, so I hadn’t been totally out of it clinically.

Fye: With the four doctors (Osler, Halsted, Welch, and Kelly) looking down at you.

Roberts: Yes. Houseofficers could sit with faculty then during lunch in the Welch Library. The Hopkins year was fantastic. I see why Hopkins is tops. I thought it was wonderful, but I loved NIH too. NIH could not have been better for me. It just flowed like a beautiful river for me. I worked hard. I didn’t feel sorry for myself. I loved it. I usually had three fellows every year, and they worked hard. I had some wonderful fellows. I used to stay in at least 2 nights a week. For 6 years after returning to NIH (we lived only a block away) I went back to work virtually every night after dinner after putting the kids to bed. Until my last 2 years, I spent all day every Saturday at NIH. Those evenings and Saturdays were when I did most of my writing and thinking. I frequently worked with a fellow during those evenings and Saturdays.

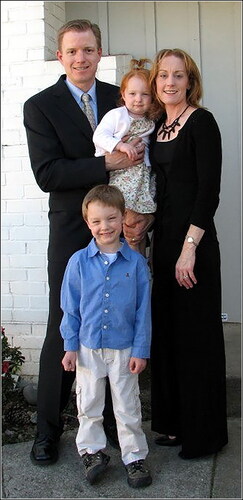

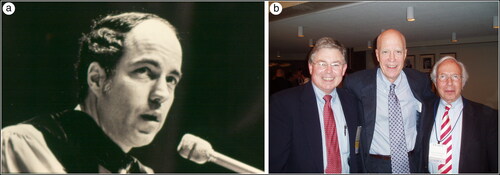

NIH changed, and my marriage of 36 years split up in 1991, which was a great disappointment. It was understandable. I was gone a lot. I wasn’t the best husband in the world. Carey is a good human being, but we are very different. I was barely 22 when we got married; she was barely 20. Too young. We had four offspring, and they have all turned out well (). Carey always let me have all the time I ever wanted for work. There was never any limitation, and I never limited her. She has written three books. She worked about 6 years during our marriage: 2 years as director of the Montgomery County Bicentennial Commission, 2 years as director of public relations for a bank, and 2 years as director of public relations for a local hospital. She wrote a historic novel (Tidewater Dynasty) in 1981 and two murder mysteries (Touch a Cold Door and Pray God to Die) after that. She also read a book virtually every day we were married. She could read a book in about 2 hours. She taught the Evelyn Wood Reading Dynamics course locally for a period. She also taught speed reading at the Williamsburg Heart Program for 3 years.

Figure 7. His children about year 2000. Daughter, Frances Carey, with John, Charles, and Cliff. Frances received an engineering degree from SMU, worked for Oracle for several years, married, and now is a homemaker with three young children. John (left) is the chief executive officer of SugarCMR, a software company in San Jose, California. Charles (middle) is chief of the Department of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery at Winchester Medical Center in Winchester, Virginia. Cliff (WCR Jr.) (right) obtained an MBA, worked for two different transportation companies, and eventually developed his own company, which he later sold. He now teaches in the public school system in Atlanta, Georgia.

Figure 8. His clan, showing three of the offspring and their children, which now total 11 grandchildren. (John and his family are not in the picture but are shown in .)

Fye: She just absorbed books?

Roberts: Yes. I would have to pump her to find out what she was reading. In contrast to me, I had to own a book to read it, whereas she would go to the library, get seven books, take seven back every week. She never cared about owning the books she read.

Fye: You know where I am on that scale. When did you discover that you had such a passion for writing? Obviously it is a passion. You don’t produce 1400 articles unless you really derive pleasure from writing them.

Roberts: When I first started the pathology residency at NIH, the head of the pathology department, Louis B. Thomas, who had trained at the Mayo Clinic, said “Boys, I am sure you will be able to write some case reports while you are here.” I said to myself, “Wow.” Then, the “cardiac pathology” was thrown into my lap. That was when I went to Jesse Edwards’ writings for help. Once I did an autopsy on a patient who died shortly after closure of a large ventricular septal defect with the aorta shifted to the right and a large muscular bundle between the base of the aortic valve cusps and the anterior mitral leaflet. I must have spent 6 hours photographing that heart. I examined it daily and about the time I was about to figure it out, Jesse Edwards published an article on double outlet right ventricle. I said, “That is it.” Jesse wrote a 217-page section in Gould’s Pathology of the Heart and Blood Vessels. Every time I saw a case of tetralogy of Fallot or transposition of the great arteries I read Edwards’ chapter in the Gould book on that topic. Charles C. Thomas published Gould’s book. Gould wrote 103 pages in the 1198-page book. The book was important because of Edwards’ contribution.

Fye: Did you get to know Dr. Edwards very well? Did you see him at meetings and talk to him, or was this mainly just reading what he wrote?

Roberts: Mainly reading what he wrote. I interviewed him much later.Citation4 That was a pleasure. The interview was in his home in St. Paul. Jesse’s monograph on corrected transposition of the great arteries was magnificent. He simplified a very complex entity by first settling on whether the patient had situs inversus or situs solitus. The definition of corrected transposition was the same irrespective of the type of situs. He simplified a lot of different congenital cardiovascular conditions. At Hopkins I had a patient with corrected transposition so I presented the Edwards concepts about that condition at the weekly cardiology conference. Soon afterwards I was offered a job at Hopkins.

Fye: I can believe that. I first met you at Hopkins when I was a fellow and you would come up and give those regular cardiac pathology conferences. I remember those very well.

Roberts: I am very indebted to Gene Braunwald for showing me how much effort it takes to produce something good. I am indebted to Glenn Morrow for offering me a job at NIH and trusting me with his surgery patients. He taught me a lot about writing. He was a cautious surgeon; he never wanted to hurt anybody. Today, I think, there are too many cardiac operations. I was at NIH during a glorious period. I loved it. I also was very lucky.

I left NIH on February 28, 1993, and fortunately went to a splendid medical center in Dallas, where I am very happy and challenged. I wasn’t getting any younger. My marriage of 36 years had just broken up. I had spent 32 years at NIH. Although I got renewed at NIH after 30 years in the Public Health Service (the other time I was in the Civil Service), the renewal would have to be done every 3 years thereafter, and I did not like that. It was also getting hard to get good fellows at the NIH. NIH had eliminated the cardiac surgery program in 1987. (I thought that was a terrible mistake.) I thought if I was ever going to leave NIH I had better get out because I was already 60. Bob Bonow offered me a position at Northwestern, and I was looking at a pathology department chairmanship in Richmond at Virginia Commonwealth University (formerly Medical College of Virginia), but I didn’t want to be a pathology chairman. I had been offered that before (at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston and at Vanderbilt University in Nashville), and I knew that I didn’t want to do that because it would have been hard to stay in heart disease if I did.

I went to BUMC in August 1992 to give a talk at medical grand rounds, and shortly thereafter one of the administrators, Tim Parris, came to Washington, DC. He looked over my lab and office and took me to dinner. (Nobody before had ever come to my place when offering me a job.) He wanted to see what I had, and I was impressed by that. Then I visited BUMC and learned, among many things, that it had a 400-person construction company owned by the hospital. That impressed me. BUMC had a fantastic fitness center, good enough that the Dallas Mavericks at one time practiced there. It also served as BUMC’s rehabilitation center. The people at BUMC were very kind and gracious. They built me a lab. I liked the atmosphere. It has worked out beautifully. This is only my second job.

Fye: There again we are alike; I have had only two jobs. When staying at your home I fell upon Carole Warnes’ big thick dissertation. She is the adult congenital heart disease guru and maven now at the Mayo Clinic. Say a few words about Carole if you wouldn’t mind.

Roberts: Carole Warnes is a lovely lady and fine doctor. She was a fellow with me at the same time that Elizabeth Ross was there. Earlier, I had seen Jane Somerville in London and said, “Jane, I am looking for a good fellow,” and she mentioned that Carole Warnes had just worked with her. Carole joined me and did a great job. As you know, I direct a heart disease program at Williamsburg, Virginia, and always took the fellows to Williamsburg and in some way tried to get them involved in the program. At one lunch there, Carole sat next to Jack Spitell, the Mayo Clinic peripheral vascular specialist, who was speaking at that program. By the time lunch was finished, Jack had invited Carole to visit the Mayo Clinic. Carole was about to finish her 2-year fellowship with me. The rest is history.

Fye: Jack Spitell was one of the few physicians who could talk about peripheral vascular disease in that era.

Roberts: He was an enthusiastic teacher of peripheral vascular disease. He was always a hit at Williamsburg. Carole Warnes had training in internal medicine, adult cardiology, pediatric cardiology, and cardiac morphology. The Mayo Clinic has been magnificent for her.

Fye: What were your thoughts about Jesse Edwards’ leaving the Mayo Clinic? How much of his success do you think was context and how much of it was Jesse Edwards?

Roberts: I think opportunities provided by an institution are important, but I think that Jesse Edwards would have done well no matter where he was. He went to a private hospital in St. Paul. (They obviously paid him more money than did the Mayo Clinic.) He consulted at the Mayo Clinic periodically thereafter, I understand. John Kirklin mentioned to me one time that Jesse never really left the Mayo Clinic but, yes, he did. He built a “cardiac registry” of hearts he obtained, mainly locally, primarily from the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis. He rapidly got fellows to spend a year or two with him. He got an NIH grant to pay the fellows and support his cardiac laboratory. He started visiting right away at the University of Minnesota and then he would bring the hearts back to his place. Thus, he built his own Mayo Clinic–type thing, beginning with the University of Minnesota at Minneapolis. He also got hearts from around the country.

When I was at NIH I went to 11 or 12 hospitals in the area every month, put on a heart conference, brought the hearts back to NIH, photographed them, and sent reports and photographs to the sender. Everybody won. I went to Georgetown University Medical Center weekly, thanks to W. Proctor Harvey. To become a specialist in cardiac morphology one needs a city, not a hospital. Today there are fewer autopsies, and the autopsy rate continues to fall.

Fye: Don’t you think a significant factor in their disappearance is the perception that many imaging techniques are now as good as or better than the autopsy?

Roberts: That is a factor. If malpractice was not an issue, there would be more autopsies. Clinicians fear missing diagnoses. Pathologists are rarely trained in cardiovascular disease. General pathologists are not experts in cardiovascular disease, through no fault of their own, and the number of superb cardiac pathologists now can be counted on one hand. Pathologists cannot make a living from heart disease. Physicians do not go into pathology if their interest is heart disease. I am an exception, and my career has been made possible by a salary provided by the federal government (NIH) or a foundation (Baylor Health Care System). I was told that on the pathology boards recently there was only one question on cardiovascular disease. Cardiologists should be cardiac pathologists. Autopsies on cardiovascular cases should be done by cardiovascular pathologists, or at least the hearts should be opened by them. Neuropathologists have more successfully convinced general pathologists that they should “open” the brain. Cardiovascular pathologists have been far less successful in convincing general pathologists that they should open the heart. General surgeons do not do heart surgery.

Several of my NIH fellows became very good cardiac pathologists as well as cardiologists: D. Luke Glancy, Bernadine Healy, Jeffrey Isner, Ernest Arnett, Bruce Waller, Henry Cabin, Carole Warnes, Marc Silver, Jessica Mann, Fred Dressler, Allen Dollar, David Gertz, and Jamshid Shirani. Several previously trained pathologists became superb cardiac pathologists: Max Buja, Renu Virmani, Bruce McManus, and Amy Kragel. Many general pathologists, unfortunately, do not look favorably at cardiovascular pathologists.

Fye: Do you believe the various specialists should be brought together around particular organ systems?

Roberts: Absolutely. That is the way IBM would set up a medical school. Braunwald discussed this matter beautifully in the June 2006 issue of The American Journal of Medicine.Citation5 Departments are useful for training houseofficers but not for practicing.

One attraction BUMC held for me was its desire to produce a heart and vascular hospital. When I arrived at BUMC, some in the Department of Internal Medicine apparently thought I was there to separate the cardiology division from the department. I actually had no interest in that. (That topic was being discussed in medical journals at the time.) In reality, the cardiology practice is already separate from the rest of internal medicine. Departments are useful for administrative purposes, but cardiologists have far more contact with cardiovascular surgeons than they do with other subspecialists in internal medicine.

Fye: When do you think the reordering of academic medical centers will occur? Most cardiologists practice in single-specialty groups where the notion that they report to a department of medicine just doesn’t exist. It is an academic structure that evolved in the 1930s. Do you have views about obstacles and tensions between cardiologists and radiologists in terms of the imaging? Imaging is sort of a premortem autopsy in some respects.

Roberts: No question. An echocardiogram or a computed tomographic image is a live autopsy. It is an economic and political situation. Chairmen of academic departments of medicine do not want to lose cardiology because it is such a money maker. The chair of medicine in most universities now has an impossible job, in my view. William Osler, who knew most information available at the time about every subspecialty, was in a great era. He did not determine salaries or seek research grants. In my view, Michael Emmett at BUMC has the best chairmanship of a department of medicine in the country. His is more like William Osler’s position at Hopkins. You have talked about how cardiology has changed since President Kennedy was killed in 1963, and it is absolutely mind-boggling. No subspecialties have achieved more than cardiology and cardiovascular surgery and cardiovascular radiology have in the last 40 years.

Fye: Let me turn to your educational life. Your writings have brought information and maybe some opinions to many. The breadth of your writings is vast. How did you become involved in continuing medical education?

Roberts: At NIH around 1965, having about 25 autopsies from the National Heart Institute a year, I said to myself, “Roberts, you cannot survive on this kind of number.” I was lucky in Washington, DC. Proctor Harvey looked out for me and gave me an incomparable platform. He had a cardiology conference every Thursday night at Georgetown University Hospital from 8:00 to 10:00 pm, and for literally 20 years I gave a 5-minute talk at one of his conferences each week. One of his cardiology fellows would call me on Wednesday and say, “Do you have something on scleroderma heart disease or rheumatoid arthritis of the heart?” and I would talk on that topic. Abner Golden was chairman of the pathology department at Georgetown, and he happened to have been one of my professors at Emory School of Medicine. They did a lot of autopsies at Georgetown, so it wasn’t very long before Proctor Harvey started a conference in cardiac pathology. Abner Golden agreed to it and then through the pathology residents I took the hearts back to NIH. I would send the Georgetown pathology residents pictures, a report, and histologic slides, so they were happy and I was happy. Then that process extended to the District of Columbia General Hospital, the Washington, DC, Veterans Administration Hospital, the George Washington University Hospital, the National Naval Medical Center (across the street from NIH), the Howard University Hospital, Suburban Hospital (also adjacent to NIH), The Johns Hopkins Hospital, the Washington Hospital Center, the National Children’s Medical Center, the Franklin Square Hospital (in Baltimore), and the District of Columbia Medical Examiner’s Office. I had faculty appointments at several of these universities. With the exception of Hopkins, I brought the hearts back to NIH, the fellows would prepare a report on them, and then the sending hospital would be sent the report plus photographs of the specimen and histology slides on the case. With the exception of Georgetown (weekly) and Hopkins (every other month) the conferences were monthly.