Abstract

William Harvey (1578–1658) discovered that blood flows in a circle and described this new finding in a short book in 1628. He had superb educational opportunities but also faced great difficulties, which he met with personal and professional resilience. A study of his life is worthwhile. Presented here are 11 lessons drawn from Harvey’s life and legacy.

KEYWORDS:

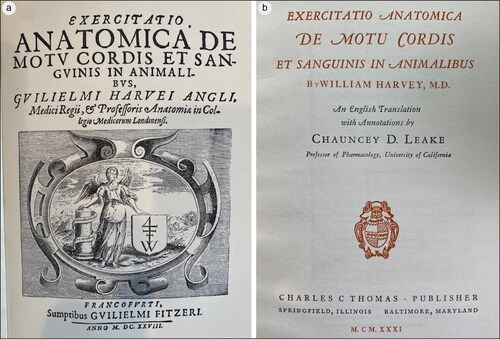

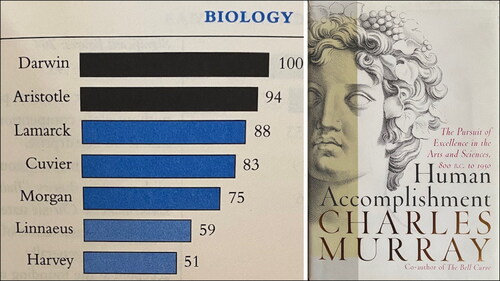

In his anatomy lectures in London in the year 1618, William Harvey (1578–1657) asserted that blood flows in a circle, challenging the authority of Galen.Citation1,Citation2 Ten years later in 1628, Harvey published a short book in Latin, De Motu Cordis (),Citation3 immortalizing him both in biology () and in medicine.Citation4,Citation5 The study of a major medical figure can be instructive. The following are some lessons from the life of William Harvey.

Figure 1. (a) Title page of Harvey’s book, left, published in Latin in Frankfurt in 1628. (b) A translation by Chauncey D. Leake published in 1931.Citation3

Figure 2. Harvey was ranked seventh in the category of biology by Charles Murray in his 2003 book, Human Accomplishment.Citation5

Understand that there are no shortcuts to knowledge. The eldest of seven sons, Harvey was bred to learning in the late English Renaissance, like Shakespeare, part of an effort to raise the family status from yeoman to gentleman. His academic training was rigorous: 16 hours a day for 6 years at Cambridge University (1593–1599) and another 2 years at Padua University (1600–1602). Like Shakespeare, he banked a treasury of knowledge through slow, deliberate study. Harvey’s education was broad, including both the humanities and the sciences. Scholars in that period were fluent in both and considered neither off limits. Like Shakespeare, Harvey also mastered disputation, a method of debate in which an understanding of traditional authorities and of the argument from each side was expected. As Zadie Smith wrote, “Our Shakespeare sees always both sides of a thing.”Citation6 It was with a balanced background that Harvey inquired into the circulation.

Go abroad. Had there been no Padua, there would be no De Motu Cordis. Some educational experience abroad at the undergraduate, graduate, or postgraduate level widens the perspective. It was in Padua that Harvey was exposed to a tradition in anatomy that included Vesalius, Fallopius, and Fabricius. Realdo Colombo was one of the Paduan anatomists whose legacies influenced Harvey; Colombo discovered (or rediscovered) the pulmonary circuit. It was in Padua that Harvey first studied the valves in veins where that inquiry was a tradition. An Italian way of thinking was undoubtedly different than an English way of thinking in the year 1600, and this exposure no doubt influenced his views the rest of his life.

Add a language. Harvey was fluent in Latin, as most European scholars were, which he learned from Canterbury Grammar School. We may also assume that he achieved fluency in Italian while living in Padua. Harvey expressed himself simply and clearly in De Motu Cordis, inserting the word “circle” and its several derivative words (circulation, circuit, circuitous) 27 times, beginning in the famous chapter 8. Two-thirds of modern English words are from French (or Latin), owing to the Norman Invasion of 1066. English speakers would do well to learn a Latin language if only to enhance understanding of the English language and to improve communication.

Seek a mentor. Both of Harvey’s books could be considered responses to books by Fabricius, his mentor in Padua, an anatomist for whom Harvey had tremendous respect. In 1603, Fabricius published a book on the venous valves arguing that their purpose was merely to limit the flow of blood from the liver to the extremities (centripetal flow). Harvey clearly took issue with this view and in De Motu Cordis made the case for centrifugal flow of blood from the extremities to the heart in the veins. Fabricius had also published a book on generation (reproduction) posthumously in 1616. Harvey’s later book On Generation in 1651 is, in large part, a contrary response. Mentors may not only expand the mind, but also serve as a traditional authority against whom one may react creatively.

Learn medical history. References or citations in a manuscript are a clue to scholarship. Harvey cited 149 persons in his anatomy lecture notes and 17 previous authors in De Motu Cordis. Aristotle and Galen were cited the most among the “ancients,” and Columbus and Fabricius among the “moderns.” Harvey was also keenly aware of the arguments of his contemporaries, such as Caspar Hofmann of Altdorf and Jean Riolan of Paris, both ardent Galenists.

Remember comparative anatomy. Harvey considered Aristotle the supreme biologist. In his anatomy lecture notes, Harvey referred to the anatomy of more than 80 animal species. In De Motu Cordis, he described 37 animal species and his own experiments in several.Citation7 His 1628 book concerns the motion of the heart and blood in animals.

Take on major subjects. Harvey’s two books were on entire systems: the circulatory system and the reproductive system. While every contribution is important on some level, it seems sensible to keep in mind an overall research goal that is broad and meaningful.

Keep in mind that major research is lifelong. Harvey was 50 in 1628 when his first book was published. He had lectured on anatomy for 12 years and carefully formulated his case. He was up against 15 centuries of Galenic tradition, in which arteries and veins were considered separate systems, where blood ebbed and flowed and was consumed in organs and tissues.

Forebear disasters. Every consequential life includes tragedies of various degrees. Harvey and his wife were not blessed with children. He failed to persuade numerous contemporaries of his “discovery,” including Casper Hofmann in 1636 in a live demonstration at Altdorf University, and Jean Riolan in correspondence. His reputation suffered with his 1628 book and his practice declined. In the English Civil War, Harvey sided with the monarchy, and the Parliamentarians ransacked his London lodgings in 1642. His vast trove of unpublished research papers and his personal property were destroyed. After 6 years of Civil War, King Charles, in whose court Harvey served with deep loyalty, was beheaded in 1649. Harvey went into retirement with a brutal case of gout and died in 1657, at age 80, while Cromwell still ruled as Lord Protector, 3 years before the Restoration. Despite these difficulties, Harvey demonstrated both personal and professional resilience.

Recognize that medical immortality is attained in publications. Without De Motu Cordis, Harvey would be rarely mentioned. The unpublished writings destroyed in his lodgings during the English Civil War are lost to history. In the Great Fire of 1666, a decade after his death, the College of Physicians building he funded, together with the medical library he donated and the statue made for him, burned to the ground in London. His book De Motu Cordis, however, continues to circulate four centuries later.

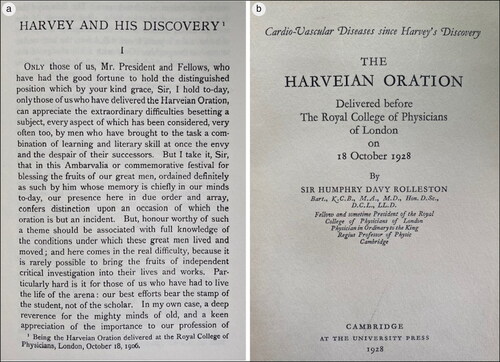

Endow education. Harvey left money in his will for the establishment of a “grammar school” in Folkstone, his hometown, which remains today (The Harvey Grammar School for Boys). The annual Harveian Oration () of the Royal College of Physicians, initially funded by Harvey, also endures as an event associated with great honor to the speaker. Educational endowments seem more durable than monuments, but perhaps neither are more lasting than publications.

Figure 3. Two examples of the annual Harveian Oration: (a) one delivered by William Osler in 1906 and (b) one by Rolleston in 1928.

Harvey has been admired and studied by many in the last 4 centuries, including Thomas H. Huxley, who wrote in 1878 that Harvey is “entitled, beyond dispute, to be regarded as the sole discoverer of the circulation of the blood, and the method of its propulsion by the heart.”Citation8 Harvey died with “the great truth” he had discovered generally accepted by medical leaders. A study of the details of his life provides many lessons for future scholars.

Disclosure statement/Funding

The authors report no funding or conflicts of interest.

- O’Malley CD, Poynter FNL, Russell KF. William Harvey. Lectures on the Whole of Anatomy. An Annotated Translation of Prelectiones Anatomiae Univeralis. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1961.

- Aird WC. Discovery of the cardiovascular system: from Galen to William Harvey. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(Suppl 1):118–129. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04312.x.

- Leake CD. Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus [Anatomical Studies on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals] by William Harvey, M.D. An English Translation with Annotations. 4th ed. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1958.

- Wright T. William Harvey. A Life in Circulation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2013.

- Murray C. Human Accomplishment. The Pursuit of Excellence in the Arts and Sciences, 800 B.C. to 1950. New York: HarperCollins; 2003.

- Smith Z. Speaking in tongues. The New York Review of Books. February 26, 2009.

- Royal College of Physicians. William Harvey and the Circulation of the Blood (videotape). https://wellcomecollection.org/works/y683v77d. Accessed August 7, 2023.

- Huxley TH. William Harvey, born April 1, 1587, died June 3, 1658. Nature. 1878;13(439):417–420.