Abstract

A formal melanoma primary prevention program was developed for a target audience of grade-school adolescents near Houston, Texas, focusing on skin cancer education and promoting long-term sun safety habits. Upon application of a multivariable regression model, adolescents of Black, non-Hispanic race, male gender, and lower grade levels were independent predictors of lower baseline skin cancer prevention knowledge. These findings reveal potential areas to prioritize when addressing knowledge gaps in the adolescent community.

Melanoma is the fifth most common cancer in the US, accounting for over 80% of skin cancer deaths.Citation1 Pilot melanoma awareness programs have demonstrated efficacy, but still have ample room for improvement.Citation2,Citation3 We developed a pilot melanoma prevention program at our institution and highlight its execution.

In an ongoing partnership with the John Wayne Cancer Foundation, volunteers are trained to deliver presentations to grade-school children with the goal of increasing melanoma prevention knowledge. Emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic, options of fully virtual, in-person, or a hybrid format are offered depending on school or teacher preference. Presentations are evenly spaced throughout the year, pausing for summer break, and take 30 and 45 minutes for grades kindergarten to 5 and 6 to 12, respectively. Presentations consist of a slideshow containing melanoma anecdotes with information relevant to melanoma prevention. Volunteers are specifically trained to be interactive and elicit ideas from students. For younger students, more visual cues are utilized and content such as mortality is excluded. Volunteers are encouraged to interact more with younger audiences.

Active outreach was used to address a suboptimal response rate, such as described with a comparable program at Mayo Clinic Alix School of Medicine.Citation4 Growing more connected to schools, we have since created an agreement with school district administrators to include our presentations in the formal curriculum. Another challenge we faced was volunteer recruitment, which we addressed by partnering with our medical school to incentivize medical student participation through a dean-sanctioned service-learning program. This provided a steady volunteer base with the capability to reach new, incoming grades with long-term consistency.

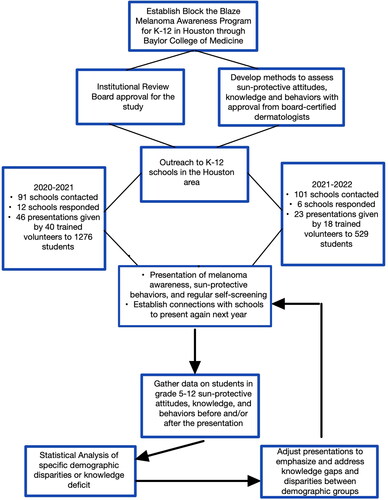

We hope to ultimately assess if our primary prevention efforts result in changes in attitudes toward melanoma prevention. With a continuous volunteer base to reach new classes, we aim to build a constantly evolving primary prevention program that is calibrated in ways that are supported by quantitative data (). Additionally, we hope to share baseline findings that may identify specific areas or groups to prioritize for the melanoma prevention curriculum.

METHODS

The Baylor College of Medicine institutional review board approved our proposal to assess attitudes and knowledge related to skin protection and waived the necessity for participant consent due to minimal risk of survey research. At the beginning of each presentation, designed by the John Wayne Cancer Foundation as part of its “Block the Blaze” program, students were asked specific true/false questions derived from Lucci et al (Supplementary Table 1), which assess melanoma prevention knowledge.Citation5 Participation was incentivized by raffle entries for $5 gift cards. Demographic information was collected with the primary correlative measure being knowledge content prior to our presentation. All students in grades K to 4 were excluded. Responses were collected from October 14, 2020 through May 25, 2021. To assess potential demographic disparities between our students, we used univariable Kruskal-Wallis testing followed by a multivariable, quasi-Poisson logistic regression model. This evaluated for demographic variables that remained significant predictors of higher knowledge content even after accounting for effect modification of other covariables. For predictor variables with more than two categorical variables (e.g., race or education level), we applied a post hoc Dunn test with Benjamini-Hochberg adjustment to determine which categories differed. All demographic variables including race, ethnicity, and gender and whether the survey respondent was first-generation were self-identified. For these demographic variables, survey respondents chose one choice out of the possibilities listed in . As an operational error, the survey design was suboptimal and incorrectly asked respondents to self-identify race and ethnicity in a mutually exclusive fashion. For age and grade level, survey respondents could select age values 1 to 25 and grade levels 1 to 12.

Table 1. Baseline knowledge in adolescents from grades 5 to 12 in response to the question “sunscreen with an SPF of 2 means that anyone can stay in the sun for 2 hours without getting a sunburn, true or false?”

RESULTS

Students (n = 1152) were asked the question: Sunscreen with an SPF of 2 means that anyone can stay in the sun for 2 hours without getting a sunburn, true or false? All results and descriptive data can be found in . By multivariable analysis, we found that male students answered accurately at significantly lower rates than female students (62% vs 79%, P < 0.001). Additionally, students who identified as Black, non-Hispanic answered incorrectly more frequently than other racial groups (P < 0.001). By post hoc testing, it was revealed that differences existed between Black, non-Hispanic individuals versus Hispanic individuals (62% vs 75%, P = 0.04), Black, non-Hispanic individuals versus those who identified as multiracial (62% vs 85%, P = 0.001), and Black, non-Hispanic individuals versus White, non-Hispanic individuals (62% vs 76%, P = 0.006).

Those who were in grades 9 to 12 were found to have higher accuracy (76 vs 66%, P < 0.001). Furthermore, while univariable analysis showed significant differences in students with varying highest parental education levels, the significance was not retained through multivariable analysis. Of note, those students who were not first generation in the United States had higher accuracy with borderline significance (77% vs 69%, P = 0.06) by multivariable analysis.

DISCUSSION

The question “Sunscreen with an SPF of 2 means that anyone can stay in the sun for 2 hours without getting a sunburn, true or false?” was chosen because sunscreen knowledge is critically important, and incorrect perceptions hold implications for the development of skin cancer. SPF, sun protective factor, measures how well sunscreen will protect skin from ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Technically, it is the ratio of the minimal erythema dose (MED) of UV light required to cause sunburn in sunscreen-protected skin to the MED of UV light required to cause sunburn in unprotected skin.Citation6 For example, if a product with SPF 50 is applied, it will protect skin until it is exposed to 50 times more UV radiation compared to that of unexposed skin.Citation6 The American Academy of Dermatology currently recommends a sunscreen of SPF 30 or higher.Citation7 Thus, an incorrect perception elicited by our question could indicate that adolescents believe that an SPF of 30 indicates that sunscreen reapplication is not necessary for 30 hours. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends reapplication every 2 hours, regardless of SPF levels, so failure to reapply sunscreen for an extended period may result in UV damage, which cumulatively increases risk of melanoma, especially if starting at a young age.Citation7 Though there has been controversy regarding whether sunscreen use could be associated with an increased risk of melanoma, large-scale metaanalyses have not found this relationship to hold true. Such investigations have concluded that sun exposure is the most important etiology in melanoma development. Thus, sunscreen and other sun-protective techniques, particularly solar dose minimization including solar avoidance, remain the primary preventive strategies.Citation8

Interestingly, race, gender, and grade level were found to be independent predictors of baseline knowledge by multivariable analysis, even after accounting for effect modification for covariables on each other. For instance, a larger percentage of Black, non-Hispanic students selected incorrect answers to the question we analyzed, as compared to White non-Hispanic, Hispanic, or multiracial students. It is already known that certain attitudes, such as the belief that people with dark skin are highly resistant to skin cancer, exist in minority groups.Citation3,Citation9 Weig et al also demonstrated that a barrier to sunscreen use was related to the feel or appearance of sunscreen in over a third of cases.Citation10 In darker pigmented individuals, the contrast between sunscreen color and their skin color is often more noticeable, and this may further dissuade regular use or reapplication. Lack of desire to wear sunscreen along with false notions that one’s inherent skin color is naturally protective against UV light could result in a lower desire to address knowledge gaps related to sun safety.

Since ethnicity and race were mutually exclusive responses in our survey, the specific race designations are most approximately interpretable as non-Hispanic individuals of the specified race for those who did not identify as Hispanic and Hispanic ethnicity of any race for those who did identify as Hispanic. This is a key limitation to our study.

Nonetheless, we have posited a question to adolescents in a diverse metropolitan city that assesses a specific knowledge gap in sun safety, as well as associated demographic disparities. However, sun safety is a broad topic, and there are many potential content areas that may have varying degrees of knowledge deficiency or demographic disparity. Understanding the specific areas that a sun safety curriculum targets may lead to personalized improvement in sun safety knowledge or behaviors. With our example, it may be beneficial to emphasize SPF education in adolescent individuals that are predominantly Black of lower grade ranges or male. It may also help to assess the root cause of false perception in sun safety knowledge.

UV light mutations begin accumulating from a young age, so skin cancer interventions that instill good habits at early ages are important. Whether tailored skin cancer education increases the general knowledge base or reduces the discrepancy between certain demographic groups is an area for future research. We hope that our development of a community primary prevention program may guide others and share our methods, outcomes, and measured variables to encourage heterogeneity in other investigations. While the execution and impact of community-level intervention related to primary prevention of melanoma is still an area of development, we believe that curricula and programs derived from quantitative evidence will have a large role in establishing lifelong sun-safe habits beginning at an early age.Citation3

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.2 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Anthony Lucci, Lauren Fraga, Mayra De La Cruz, Yasmin Khalfe, and the John Wayne Cancer Foundation for their guidance and support in conducting this project.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Funding was provided by the Texas Medical Association Alliance. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

- Saginala K, Barsouk A, Aluru JS, Rawla P, Barsouk A. Epidemiology of melanoma. Med Sci (Basel). 2021;9(4):63. doi:10.3390/medsci9040063.

- Hughes BR, Altman DG, Newton JA. Melanoma and skin cancer: evaluation of a health education programme for secondary schools. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128(4):412–417. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00201.x.

- Jacobsen AA, Galvan A, Lachapelle CC, et al. Defining the need for skin cancer prevention education in uninsured, minority, and immigrant communities. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152(12):1342–1347. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3156.

- Abdelwahab R, Abdou M, Newman C. Piloting a community education skin cancer program coordinated by medical students. JMIR Dermatol. 2022;5(3):e36793. doi:10.2196/36793.

- Lucci A, Citro HW, Wilson L. Assessment of knowledge of melanoma risk factors, prevention, and detection principles in Texas teenagers. J Surg Res. 2001;97(2):179–183. doi:10.1006/jsre.2001.6146.

- Latha MS, Martis J, Shobha V. Sunscreening agents: a review. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6(1):16–26.

- Sunscreen FAQs. https://www.aad.org/media/stats-sunscreen. Updated February 17, 2023. Accessed April 22, 2023.

- Huncharek M, Kupelnick B. Use of topical sunscreens and the risk of malignant melanoma: a meta-analysis of 9067 patients from 11 case–control studies. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(7):1173–1177. doi:10.2105/ajph.92.7.1173.

- Buchanan Lunsford N, Berktold J, Holman DM, et al. Skin cancer knowledge, awareness, beliefs and preventive behaviors among Black and Hispanic men and women. Prev Med Rep. 2018;12:203–209. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.09.017.

- Weig EA, Tull R, Chung J, et al. Assessing factors affecting sunscreen use and barriers to compliance: a cross-sectional survey-based study. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(4):403–405. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1587147.