Abstract

Examining the history of vaccination in the Civil War reveals lessons about why citizens resisted vaccination and how physicians tried to respond to the problems associated with combating epidemic diseases like smallpox. The Confederate government and physicians failed to effectively advocate to the public and collect information in an organized manner, and they suffered failures in getting enough citizens and soldiers vaccinated. Some Confederate physicians like Joseph Jones studied vaccination, but this came after the war, and the Confederate government failed to embrace and combat vaccine hesitancy. In some cases, more radical political elements tried to control the conversation through newspaper articles. Criticisms of vaccination likely continued to haunt the perceptions of vaccination in the Southern United States.

Attitudes in the South regarding vaccinations vacillated before, during, and after the Civil War.Citation1–5 Former Confederate medical officers, though initially critical of their own work during the war, emphasized vaccination successes and innovations in postwar histories.Citation1–6 The Union was not without its own examples of hesitancy or resistance of soldiers and civilians against the smallpox vaccinations, although it had more organized vaccination efforts in comparison to the Confederacy.Citation2,Citation5,Citation6 This article argues that Confederate newspapers, memoirs, and physicians accounts often had contradictory and confusing information, and similar confusion and misinformation challenge vaccination efforts in the US South today.Citation7,Citation8

VACCINATIONS AND NEWSPAPERS

The Confederacy experienced problems vaccinating their soldiers and the Southern populace during the American Civil War (1861–1865).Citation9,Citation10 The Confederate Medical Department tried to vaccinate White citizens against smallpox. The method of vaccination the Confederacy used was inoculation through variolation, which involved transferring scabs from sick individuals to patients wanting protection from smallpox.Citation2 The reports of “spurious vaccination,” which referred to “false” or “incorrect” inoculation, spread fear to Southern citizens, as they read accounts of disfiguration and the spread of syphilis in Southern newspapers.Citation1,Citation2,Citation9,Citation10 The North and the South both had problems with vaccination efforts, but scholars generally regard the Confederacy as having far more difficulty.Citation2,Citation5 Confederate physicians worked to provide a counternarrative to these newspaper accounts and wanted to win public support for smallpox vaccination.

Prior to the Civil War there was optimism and concern about vaccination in newspapers. The Camden Gazette in 1817 described no problems with vaccination and described the elimination of smallpox.Citation11 Newspaper articles also contained concerns about vaccinations, including skin conditions like “erysipelas,” which appeared in Southern newspapers in 1863. The Abington Virginian ran a warning from the Augusta Constitutionalist that though vaccination materials were plentiful in the Confederacy, “great care should be taken that the matter for vaccination should be taken from a perfectly healthy person.”Citation12 In the 1862 Southern Cultivator there was a plea for both “families” and “servants” to become vaccinated against smallpox.Citation13 The plea included justifications for vaccinations and methods for how to administer vaccinations to the household, as smallpox was a “horrible disease” ().Citation13 The Southern Cultivator recommended getting a medicine that covered up physical disfiguration from vaccination.Citation13 In 1862, Confederate Surgeon William Henry Cumming, who served as “superintendent vaccination” in South Carolina and Georgia, published a promotional article for vaccination.Citation14 Cumming wanted to use the railroad to distribute vaccines and wanted to use the centralized railroad convergence of Atlanta.Citation14 Some towns even advertised that they were smallpox free because of vaccination, like Camden in 1863.Citation15

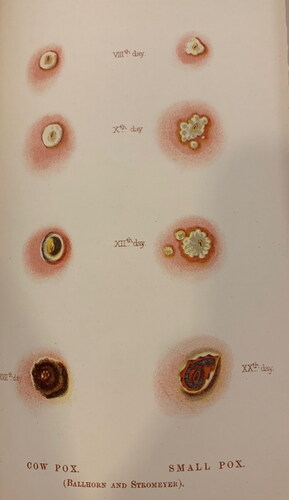

Figure 1. Cowpox and smallpox pustules by day, from Edgar M. Crookshank, History and Pathology of Vaccination, Volume 1. London: H. K. Lewis, 1889. Courtesy of Peggy Balch, Reynolds-Finley Historical Library, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

In 1863, North Carolina passed laws and made fiscal allocations to get people vaccinated, but received criticism for supporting vaccination. The Western Democrat reported that North Carolina dedicated $30,000 to stop the spread of smallpox and get its citizens vaccinated, appointing a surgeon for every county.Citation16 The newspaper criticized the legislature’s actions: “We doubt the propriety of making an appropriation for the purpose, as those who desired to be vaccinated have already been; besides, it creates too many salaried offices, and will do little or no good.”Citation16 In criticizing the economics and discretion of the legislature, the newspaper charged that “the Legislature has appropriated money with an unsparing hand and it may be useless now to talk about the necessity for economy.”Citation16 They criticized state vaccination efforts, as they argued that they increased disease and killed more people than smallpox itself.Citation16 But not all parts of the South were critical of vaccination in 1863. The Memphis Daily published an editorial written by a physician from Columbus, Mississippi, who promoted proper vaccination.Citation17 Union victors emphasized the importance of vaccination, such as in the newly liberated city of Savannah, Georgia, and planned vaccinations to improve the health of the city.Citation18

Southern newspapers became aggressive and angry at Union vaccination efforts as the Civil War continued. In 1864, The Daily Dispatch ran a story about news (or rumors) of prisoners of war who had received vaccinations by command of the Union Army. The paper charged that the vaccination materials were poor and resulted in their literal dismemberment: “Many of our men had their arms amputated, and a number died within a week after vaccination.”Citation19 The article then mentioned that forced vaccination, with poor materials, had also occurred at other Union-controlled prison camps in Ohio: “This same fiendish act was perpetrated on our Camp Chase prisoners in Ohio some two years ago, when many of our men were inoculated with a disease too horrible to mention, and died a loathsome death or were rendered miserable for life.”Citation19 The article concluded with a sentence meant to enrage the audience: “Is there no limit to Yankee inhumanity?”Citation19 In the same Confederate newspaper, there were advertisements from Confederate surgeons, under orders, offering vaccinations to “healthy white children” without charging any fees.Citation19

CONFUSING ACCOUNTS OF SPURIOUS VACCINATIONS

The Confederacy had major outbreaks of smallpox, and vaccines were potential tools to end the epidemic.Citation2–6,Citation9,Citation10 Problems with vaccination began to hinder Confederate efforts, especially the dangerous effects that resulted from failed vaccine efforts of “spurious” or fake vaccination such as skin infections, syphilitic lesions, or the inadvertent spread of smallpox.Citation10 British physicians like Thomas Hawkes Tanner, who were interested in the promotion of vaccination, studied spurious vaccination in the Confederacy.Citation20 Tanner explained proper vaccination for smallpox, which included the transfer of scabs (called “vaccina”) from sick persons, with doctors implanting those scabs under the skin of patients.Citation2,Citation5,Citation10,Citation20 Sometimes in the Confederacy, cows produced smallpox vaccina that physicians used to “vaccinate” soldiers and avoid the risk of the spread of syphilis.Citation2,Citation5,Citation10,Citation20 The term vaccinate described the act of providing soldiers potential immunity from smallpox and was often used interchangeably in newspapers and medical literature in the South. Self-vaccination, like those that occurred in the Confederacy, produced a rare condition of erysipelas (a type of skin infection).Citation2,Citation20 Tanner concluded that the failed cases during the American Civil War did not dilute the value of vaccination, as they were exceptional and resulted from physicians who lacked skill.Citation10,Citation20

Tanner’s research included accounts from the Confederate surgeon S. E. Habersham regarding spurious vaccination at the Chimborazo Hospital in Virginia. Habersham mentioned patients suffering syphilitic ulcers from spurious vaccination. He studied the pus from the patient’s skin lesions with a microscope in order to understand problems associated with vaccination.Citation21 Habersham included vaccination problems in the Northern Army, as there were cases of spurious vaccinations in Union prisons.Citation21 He claimed to not know of any cases of spurious vaccination in the Confederate Army and proposed that the atmosphere or blood issues explained spurious vaccination.

Other Confederate surgeons like O. Kratz also published research on spurious vaccination and advocated for further study. Kratz proposed an explanation for spurious vaccination, as it was an uncontrolled fermentation reaction in the body that caused vaccination problems.Citation21,Citation22 The medical director of the Army of the Frontier (Union) published a report in 1863 criticizing Confederate vaccinations of soldiers and civilians.Citation23 Union surgeons caring for Confederate soldiers and dissenters transmitted accounts of spurious vaccination.

Attitudes against vaccination in the Confederacy can be summed up by Union officers writing the history of the Civil War after its conclusion: “Untoward results of vaccination appear to have been at one period the rule rather than the exception among civilians as well as soldiers within the Confederate lines,—so much so that for some time after the war the people, and in some instances even physicians, manifested a fear of resorting to this protective measure.”Citation23 Former Confederate surgeons and physicians in 1877 voiced support for vaccination in the North Carolina Medical Journal.Citation24 The editorial claimed the Confederate Army made mistakes with vaccinations spreading syphilis, but later avoided the problem by using materials from its cattle and argued that there were more cases of spurious vaccination in the North than admitted.

Joseph Jones was a Confederate surgeon who received his education in the North. He studied spurious vaccination and published his findings in 1867.Citation1,Citation25 Jones gathered circulars, reports, and published materials mentioning spurious vaccination after the war and wanted to know more about contagion, but could not fully complete it and complained that “these labors were brought to a sudden and unexpected close, by the disastrous termination of the civil war.”Citation1

The Confederate Andersonville prison camp was one of the most disease-ridden prison camps of the Civil War, and the United States charged the leader of the camp, Captain Henry Wirz, with war crimes.Citation25–27 Charges included Wirz’s responsibility in improperly vaccinating prisoners at Andersonville. Prosecutors questioned Wirz after the war about vaccination in the camp, along with other problems of camp diseases, and how much he knew about spurious vaccination in the South. His attorneys appeared in the transcript with the defense that “the same effects experienced from vaccination at Andersonville had been experienced throughout the whole South; that the same vaccine matter used at Andersonville, was, so far as could be ascertained, used in various places throughout the South, and had similar affects on soldiers and private citizens.”Citation25–28

The court decided that even if the defense could prove widespread dangers of vaccination, or even “poisoning” people in the South, Wirz was still responsible.Citation26,Citation27 Wirz then shared his knowledge of problematic Southern vaccination, such as in Bragg’s army in Tullahoma, Tennessee, where he served in a medical position. He estimated that the army had 1000 soldiers incapacitated from “spurious vaccination,” some even having syphilis.Citation25–28 Joseph Jones, former Confederate surgeon, testified for the prosecution. Jones visited the camp and examined the poor conditions, which he testified to during the trial.Citation25–28

CIVIL WAR MEMOIRS

It was only years after the Civil War that some Confederate physicians tried to counter vaccine hesitancy, and they often rewrote histories to emphasize the success of the Confederacy. Former Confederate physicians later emphasized the openness of Confederate citizens to variolation and left out any stories of resistance toward Confederate vaccination efforts.Citation3,Citation29

At the 1912 meeting of the American Public Health Association, attendees heard a presentation from a former Confederate doctor, who presented the successes of vaccination efforts against smallpox in Richmond. The presentation caused another physician in the audience to proclaim that Confederate citizens were an exemplary model for the support of vaccination.Citation3

After the Civil War, memoirs from Confederate veterans discussed vaccination efforts and included narratives that they hoped would demonstrate their own heroics and morality in regard to vaccination. John Beauchamp Jones wrote about the failures and complications of his own vaccination.Citation29 Jones used accounts of vaccination efforts to differentiate the Confederacy from the Union: Confederate vaccination efforts appeared in the memoir as honorable and successful, as Jones included a case he heard from the army of General Lee. Jones heard that “a poor old negro man” was thrown into the Rappahannock River by the “Abolition Army of the Potomac.”Citation29 The soldiers had taken the African American man away from his owner because he had been sick with smallpox and threw him into the river because the Union soldiers feared smallpox. He credited Confederate soldiers with the ability to rescue the African American man because Confederate soldiers had the protection of vaccination. Jones then shamed the Union army as lacking vaccination, with the army carrying disease.Citation29 The Confederate Army in the 1866 memoir was portrayed as more virtuous because they were vaccinated: “Our men have all been vaccinated; and their recklessness of diseases and death is perhaps a guarantee of exemption from affliction. Their health, generally, is better than it has ever been before.”Citation29

The memoir also included worries about spurious vaccination. In 1862 the Confederate Congress, according to Jones, experienced a smallpox outbreak and did not have a quorum. After the surgeon general threatened to send in his surgeons to vaccinate everyone in the Confederate Congress, a quorum occurred, though no Congressmen volunteered for inoculation.Citation29 Some Confederate government members valued vaccination, especially medical officers, but the Confederate vaccination strategy lacked a centralized vaccination policy or sharing of information.

After the war, at a reunion of the United Confederate Veterans, C. H. (Christopher Hamilton) Tebault, a former Confederate physician, explained the successful experiment that led to a safe supply of bovine-produced vaccina, producing safer vaccinations, which he claimed made soldiers more confident about the vaccine.Citation30 Tebault proudly stated to the veterans: “Fearing the bad vaccine virus, which caused many amputations as well as deaths by reason of its impurity, these returning soldiers yielded without hesitation to the fresh and pure modification inoculation, which operated a complete success in every way and from every standpoint.”Citation30

He simplified the history of vaccination in the Confederacy at the reunion. Tebault, and other postwar memoirs, omitted the problems related to spurious vaccination, giving the impression of a united Confederacy that supported vaccination. He justified the Confederacy’s actions in the Civil War, but also emphasized the contributions of the Confederacy to vaccination knowledge in medical journals. But in 1866, prior to his presentation to the veterans, Tebault gave critical accounts of spurious vaccination and criticized the Confederacy, arguing that they used poor vaccination materials resulting in injuries to soldiers and civilians, and admitting they had gathered vaccina from children.Citation31

The Confederacy attempted to vaccinate citizens and soldiers for smallpox but could not overcome the challenges of building a mass vaccination program, including addressing coordination difficulties, training physicians, sharing information, and combating misinformation. Recent COVID-19 vaccination programs faced challenges such as contesting misinformation. The history of vaccination in the South, especially during the Civil War, needs consideration in the creation of successful vaccination efforts in battling future pandemics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Shirley Laird, Mr. Scott Moss, Ms. Peggy Balch, Ms. Anna Kaetz, and Dr. David Dangerfield.

Disclosure statement

This project received support from a CISE undergraduate research grant from Tennessee Technological University and additional support from the Reynolds-Finley Research Fellowship in the History of Health Sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Jones J. Researches upon ‘Spurious Vaccination:’ or the Abnormal Phenomena Accompanying and Following Vaccination in the Confederate Army, During the Recent American Civil War, 1861–1865. Nashville, TN: University Medical Press; 1867.

- Hicks R. Scavrous matters: spurious vaccination in the Confederacy. In: Cashin JE, War Matters: Material Culture in the Civil War Era. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2018:123–150.

- Brock CWP. How the Confederate army was vaccinated. Am J Public Health. 1912;2(1):23–23. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2.1.23.

- Devine S. Learning from the Wounded: The Civil War and the Rise of American Medical Science. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2017.

- Allen A. Vaccine: The Controversial Story of Medicine’s Greatest Lifesaver. New York, NY: Norton; 2007.

- Humphreys M. Marrow of Tragedy: The Health Crisis of the American Civil War. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2017.

- Wright A. Lowest rates, highest hurdles: Southern states tackle vaccine gap. Pew, 2021. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/06/17/lowest-rates-highest-hurdles-southern-states-tackle-vaccine-gap.

- Downs J. Sick from Freedom: African American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Sartin JS. Infectious diseases during the Civil War: the triumph of the third army. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16(4):580–584. doi:10.1093/clind/16.4.580.

- Adams GW. Confederate medicine. J South Hist. 1940;6(2):151–166. doi:10.2307/2191203.

- Medical. Camden Gazette, January 16, 1817.

- A caution-erysipelas. Abingdon Virginian, February 13, 1863.

- Small Pox. Southern Cultivator, 1862:20–22.

- Vaccination. Yorkville Enquirer, December 3, 1862.

- The small pox. The Camden Confederate, February 13, 1863.

- The small pox law. The Western Democrat, February 17, 1863.

- C. M. D. Vaccination. Memphis Daily Appeal, February 18, 1863.

- A Letter from Savannah. The Alexandria Gazette and Virginia Advertiser, February 16, 1865:155–160.

- Barbarism Y. The Daily Dispatch, November 28, 1864.

- Tanner TH. The Practice of Medicine. 6th ed. London: Henry Renshaw; 1869.

- Habersham SE. Report on spurious vaccination in the Confederate army. Med Surg J. 1866;21:1–11.

- Kratz O. On vaccination and variolous diseases. Confed State Med Surg J. 1864;1(7):104.

- Smart C. The Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion, Part III. Vol. I. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1888:637–638.

- Reviews and Book Notice. Transactions of the Twenty-Eighth Annual Meeting of the American Medical Association. NC Med J. 1887;1–2:187–194.

- Breeden JO. Joseph Jones and Confederate medical history. Georgia Hist Q. 1970;54:357–380.

- Wirz H. Trial of Henry Wirz. Letter of the Secretary of War. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office: 1868.

- Breedon JO. Andersonville—A Southern surgeon’s story. Bull Hist Med. 1973;47:317–343.

- Breedon JO. Joseph Jones and public health in the new South. Louisiana Hist. 1991;32:341–370.

- Jones JB. A Rebel War Clerk’s Diary at the Confederate States Capital. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott & Co; 1866.

- Proceedings of the Convention and Adoption of the Construction of the United Confederate Veterans. Surgeon General’s Report. New Orleans: Hopkins’ Printing Office; 1819:75–79.

- Tebault CH. In: West AI, ed. Christopher H. Tebault: Surgeon to the Confederacy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland; 2020.