ABSTRACT

Ginger (Zingiber officinale) has been used as a spice and medicine for over 200 years in Traditional Chinese Medicine. It is an important plant with several medicinal, and nutritional values used in Asian and Chinese Tradition medicine. Ginger and its general compounds such as Fe, Mg, Ca, vitamin C, flavonoids, phenolic compounds (gingerdiol, gingerol, gingerdione and shogaols), sesquiterpenes, paradols has long been used as an herbal medicine to treat various symptoms including vomiting, pain, cold symptoms and it has been shown to have anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, anti-tumour activities, anti-pyretic, anti-platelet, anti-tumourigenic, anti-hyperglycaemic, antioxidant anti-diabetic, anti-clotting and analgesic properties, cardiotonic, cytotoxic. It has been widely used for arthritis, cramps, sprains, sore throats, rheumatism, muscular aches, pains, vomiting, constipation, indigestion, hypertension, dementia, fever and infectious diseases. Ginger leaves have also been used for food-flavouring and Asian Traditional Medicine especially in China. Ginger oil also used as food-flavouring agent in soft drink, as spices in bakery products, in confectionary items, pickles, sauces and as preservatives. Ginger is available in three forms, namely fresh root ginger, preserved ginger and dried ginger. The pharmacological activities of ginger were mainly attributed to its active phytocompounds 6-gingerol, 6-shogaol, zingerone beside other phenolics and flavonoids. Gingerol and shogaol in particular, is known to have anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. In both Traditional Chinese Medicine, and modern China, Ginger is used in about half of all herbal prescriptions. Traditional medicinal plants are often cheaper, locally available and easily consumable raw and as simple medicinal preparations. The obtained findings suggest potential of ginger extract as an additive in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

Introduction

Ginger occurrence and cultivation

Traditionally, Chinese medicine includes herbal medicines and acupuncture (Akinyemi et al. Citation2016; Ogbaji et al. Citation2018; Shahrajabian et al. Citation2018). Zingiber officinale is a member of the Zingiberaceae plant family, native to East and southern Asia, consisting of 49 genera and 1300 species, 80–90 of which are Zingiber. Its generic name Zingiber is derived from the Greek zingiberis, which comes from the Sanskrit name of the spice, singabera; the Latin name, Zingiber, means shaped like a horn and refers to the roots, which resemble a deer,s antlers. The plant is known as Sringavera in Sanskrit (Vasala Citation2004). Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe.) has a long history of being used as a medicine and herbal since ancient time and had been used as an important cooking spice throughout the world (Nour et al. Citation2017). It is a plant that is used in folk medicine from south-east Asia, and in Greco-Roman traditions, Brazil, Australia, Africa, China, India, Bangladesh, Taiwan, Mexico, Japan, Jamaica, the India, the middle east and parts of the United States also cultivate the rhizomes for medicinal purpose (Langner et al. Citation1998; Blumenthal et al. Citation2000; Sekiwa et al. Citation2000; Yadav et al. Citation2016). El Sayed and Moustafa (Citation2016) reported that ginger rhizome is widely used as a spice or condiment.

Ginger and the Silk Road

For centuries has been an important ingredient in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurvedic, and Unani-Tibb herbal medicines for the treatment of different diseases (Willetts et al. Citation2003; Ali et al. Citation2008; Memudu et al. Citation2012). Zingiber officinale was also one of the first oriental spices to be grown to the Europeans, it was introduced to northern Europe by the Romans who got it from Arab traders and was one of the most popular spices in the Middle Ages (Kala et al. Citation2016). Alakali et al. (Citation2009) also mentioned that ginger was one of the earliest oriental species known in Europe in the ninth century, in the thirteenth century, it was introduced to East Africa by the Arabs. In West African and other parts of the tropics, it was introduced by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century (Kochhar Citation1981). The spice was known in Germany and France in the ninth century and in England in the tenth century for its medicinal properties (Yadav et al. Citation2016). Elzebroek and Wind (Citation2008) found that Marco Polo, introduced to ginger while visiting China and Sumatra in the thirteenth century, transported some to Europe. They have also discussed how the cultivation of ginger in Mexico was initiated by the Spaniard, Francesco de Mendoza. In China, dried Ginger, known as Gan-jiang is mentioned in the earliest of herbals, She Nung Ben Cao Jing, attributed to Emperor Shen Nung (almost 2000 BC). Chinese records dating from fourth century BC indicate that Ginger was used to treat numerous conditions including stomachache, diarrhoea, nausea, cholera, haemorrhage, rheumatism, and toothaches. Not only in Traditional Chinese Medicine, but also in modern China, Ginger is used in about half of all herbal prescriptions, because of its ability to act as messenger, servant and guide herb that brings other herbal medicines to the site where they are needed (Afzal et al. Citation2001). Ginger cultivation back about 3000 years ago in India, and it remains an integral part of Indian cuisine where it is commonly used in many popular dishes (Daily et al. Citation2015). Lister (Citation2003) revealed that the ginger plant has a long history of cultivation known to originate in China and it was one of the most parts of Chinese Traditional Medicine, and then spread to India, Southeast Asia, West Africa and the Caribbean. In Korea, ginger has been used to season foods for the last 1000 years approximately (Daily et al. Citation2015). Sliced ginger with sugar added is used to make tea, pickled ginger slices (Gari) are frequently used a condiment in Japan, and ginger is commonly used to flavour cookies and cakes in Western countries.

Ginger classification and variation in species

Z. officinale Roscoe classification is Kingdom: Plantae-Plants, Subkingdom: Tracheobionta-Vascular plants, Superdivision: Spermatophyta-Seed plants, Division: Magnoliophyta-Flowering plants, Class: Liliopsida-Monocotyledons, Subclass: Zingiberidae, Order: Zingiberales, Family: Zingiberaceae – Ginger family, Genus: Zingiber P. Mill – Ginger, Species: Zingiber officinale Roscoe – Garden ginger.

Red Ginger (Z. officinale var. Rubra) is a variance of the Z. Officinale species cultivated in Indonesia and Malaysia. Moreover, having gingerols and shogaols, it is loaded with anthocyanin and tannin in its root bark. Traditionally, it is used in species, syrup and as a remedy for rheumatism, osteoporosis, asthma and cough.

Some of the countries grow with variation in species viz: Indian, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka ginger – (Z. officinale), Jamaican ginger – (Z. officinale), Chinese ginger – (Asarum splendens), Australian ginger – (Alpinia caerulea), Nigerian ginger – (Z. officinale white and yellow variety), Japanese ginger – (Zingiber mioga), Indonesian ginger – (Alpinia galangal), and Hawaiian Island – (Zingiber zerumbet) (Sandeep Citation2017). Common names of Ginger in different countries are, Chinese: Geung, Cook Islands: Kopakai, English: Ginger, Fiji: Cagolaya ni vavalagi, Hawaiian: Awapuhi Pake, India: Adrak and Inchi, Japan: Shoga, Java: San gurng, Gung Guung, San geong, Atjuga, Niue: Poloi, Solomon Islands: Papasa, Spanish: Jengibre, Thailand: Khing, Vietnamese: Gung.

Black ginger, the rhizome of Kaempferia parviflora (Zingiberaceae), has traditionally been used as food and a folk medicine for one thousand year in Asian Traditional Medicine especially in Thailand. The dried rhizome is pulverised and used as tea bags, while fresh one is utilized to brew wine. As dietary supplements, it has been made into various preparations such as medicinal liquor or liquor plus honey, pills, capsules and tablets. It has been claimed that black ginger is appropriate to cure allergy, asthma, impotence, gout, diarrhoea, dysentery, peptic ulcer and diabetes (Toda et al. Citation2016). Other notable member of this family (Zingiberacea) is turmeric otherwise called red ginger (Curcuma longa) (Akinyemi et al. Citation2015). It is a rhizomatous herbaceous perennial plant, in the ginger family, employed as a dye source food colorant due to its characteristics yellow colour (Chan et al. Citation2009). Ginger is a warm-season crop adapted for growth in tropical and subtropical regions. Best growth occurs under moist conditions and temperatures of 25–28°C. Growth efficiency declines with temperatures above 30°C and below 24°C. Ginger grows well in full sun. Vegetative growth is promoted with long day lengths, and rhizome enlargement is promoted under shorter day lengths. Ideal pH is 5.5–6.5 and it requires a deep (25–40 cm), rock-free, sandy loam soil, high in organic matter with adequate drainage that allows for proper hilling of the crop. Ginger is usually available in three different forms: (1) Fresh (green) root ginger, (2) Preserved ginger in brine or syrup, (3) Dried ginger spice. Fresh ginger is usually consumed in the area where it is produced, although it is possible to transport fresh roots internationally. Both mature and immature rhizomes are consumed as a fresh vegetable. Preserved ginger is only made from immature rhizomes. Most preserved ginger is exported, Hong Kong, China and Australia are the major producers of preserved ginger and dominate the world market. Dried ginger spice is produced from the mature rhizome. As the rhizome matures the flavour and aroma become much stronger. Dried ginger is exported, usually in large pieces which are ground into a spice in the country of destination. Dried ginger can be ground and used directly as a spice and also for the extraction of ginger oil and ginger oleoresin.

Ginger nutritional composition and chemical constituents

The main area under ginger covering is related to Nigeria 56.23% of the total global area followed by India (23.6%), China (4.47%), Indonesia (3.37%), and Bangladesh (2.32%) (Dhanik et al. Citation2017). Top ten Ginger producing country of the world has been shown in . Nutritional composition of ginger is shown in . Nutritional profile of Ginger (100 g) has been mentioned in .

Table 1. Top ten ginger producing country of the world (Dhanik et al. Citation2017).

Table 2. Nutritional composition of ginger (per 100 g) (Sandeep Citation2017).

Table 3. Nutritional profile of ginger (100 g) (Singh et al. Citation2017).

Minerals content of ginger for ginger root (Ground) consists of Calcium (114 mg per 100 g), Iron (19.8 mg per 100 g), Magnesium (214 mg per 100 g), Manganese (33.3 mg per 100 g), Phosphorus (168 mg per 100 g), Potassium (1320 mg per 100 g), Sodium (27 mg per 100 g), and Zink (3.64 mg per 100 g), and minerals contents for ginger root (Raw) are Calcium (16 mg per 100 g), Iron (0.6 mg per 100 g), Magnesium (43 mg per 100 g), Phosphorus (34 mg per 100 g), Potassium (415 mg per 100 g), Sodium (13 mg per 100 g), and Zink (0.34 mg per 100 g) (USDA Citation2013). It was found that ginger contained 1.5%-3% essential oil, 2–12% fixed oil, 40–70% starch, 6–20% protein, 3–8% fibre, 8% ash, 9–12% water, pungent principles, other saccharides, cellulose, colouring matter and trace minerals (Chan et al. Citation2009).

Ginger is called by different names in different parts of the world such as Zingiberis rhizome, Shen jiany, Cochin, Asia ginger, Africa ginger and Jamaican ginger (Peter Citation2000). Kala et al. (Citation2016) stated that ginger oil also used as food-flavouring agent in soft drink, as spices in bakery products, in confectionary items, pickles, sauces and as preservatives. There is variability in the compounding of ginger products (). The relative composition in the extraction of ginger is determined by species of ginger, maturity of the rhizome, climate in which the plants are grown, when harvested, and preparation method of the extract (Grzanna et al. Citation2005). Gaur et al. (Citation2016) also reported that agro-climatic conditions are known to influence the production of secondary metabolites in ginger rhizome when same cultivar is grown in two different locations. Ginger is affected by leaf spots, leaves may have small, whitish spots with yellow edges; these get larger and spread, making the leaf yellow then brown, killing it. Early in the crop, it can cause severe losses. Fusarium spp., Rhizoctonia spp. and Pseudomonas solanacearum have been found in diseased leaves. Ginger propagation is usually performed with rhizome but has a lot of obstacles, the obstacles among other is the availability of good quality seed rhizome (Melati et al. Citation2016). Rhizome again, filled out, no wrinkles, bright shiny skin colour, and free of pests attacks is characteristics of high-quality seed (Hasanah et al. Citation2004).

Table 4. Active chemical constituents of ginger (Kathi Citation1999).

Medicinal uses and potential health benefits in traditional medicine

Ginger has direct anti-microbial activity and thus can be used in the treatment of bacterial infections (Tan and Vanitha Citation2004). In Traditional Chinese Medicine, it is employed in colic and in atonic dyspepsia and used as a stimulant (Keys Citation1985; Grant and Lutz Citation2000; Sharma Citation2017; Yilmaz et al. Citation2018). Ginger is regarded as a Yang herb, which can decrease Yin and nourish the body (Jittiwat and Wattanathorn Citation2012). Mishra et al. (Citation2012) also revealed that ginger in Traditional Chinese Medicine, characterised as spicy and hot, and it is claimed to warm the body and treat cold extremities, improves a weak and tardy pulse, address a pale complexion, and strengthen the body after blood loss. In Traditional Chinese Medicine as herbal therapy against several cardiovascular diseases (Wynn et al. Citation2001).

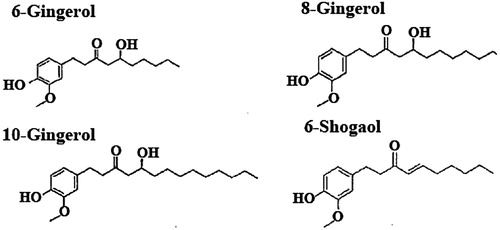

Based on the historical usage of ginger as an antiemetic agent in the East Traditional Medicine. The antiemetic effect of ginger has been known as a treatment method in traditional medicine especially the Chinese and Iranian Medicine (Eric Chan et al. Citation2011; Palatty et al. Citation2013; Naderi et al. Citation2016; Soltani et al. Citation2018). Sharma (Citation2017) explained that many of herbs and plant extracts such as ginger are based on what has been used as part of Traditional Medicine Systems and there is a large body of anecdotal evidence supporting their use and efficacy. Some other researchers emphasised that ginger plays an important role in Ayurvedic, Chinese, Arabic and African traditional medicines used to treat headaches, nausea, colds, arthritis, rheumatism, muscular discomfort and inflammation (Baliga et al. Citation2011; Dehghani et al. Citation2011). Recently, ginger rhizomes are used in Traditional Medicine as therapy against several cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension (Ghayur et al. Citation2005). Niksokhan et al. (Citation2014) reported that ginger has been used in Traditional Medicine of Iran as an anti-edema drug and is used for the treatment of various diseases including nausea, gastrointestinal disorders, respiratory disorders, athero-sclerosis, migraine, depression, gastric ulcer, cholesterol; and other benefits of giner are reducing pain, rheumatoid arthritis, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant effects. Surh et al. (Citation1998), and Manju and Nalini (Citation2010) mentioned that ginger is one of the most widely used spices in India and has been utilised frequently in traditional oriental medicine for common cold, digestive disorders and rheumatism. Ursell (Citation2000) and Oludoyin and Adegoke (Citation2014) reported that ginger is a perennial plant with narrow, bright green, grass-like leaves, and it is cultivated in the tropics for its edible rhizomes and has been found to be useful for both culinary and medicinal purposes. Schwertner and Rios (Citation2007) reported that the main components of ginger are 6-gingerol, 6-shogaol, 8-gingerol, and 10-gingerol and these constituents have previously been shown to exhibit strong antioxidant activity. 6-gingerol was reported as the most abundant bioactive compound in ginger with various pharmacological effects including antioxidant, analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties (Kundu and Surh Citation2009; Dugasani et al. Citation2010). The shogaols can be partially transformed to paradols upon cooking or metabolised to paradols in the animals, body after being consumed and absorbed by digestive system (Wei et al. Citation2017). Gingerol and shogaol in particular, is known to have anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Kim et al. Citation2005) ().

Figure 1. Structure of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol and 6-shogaol (Zick et al. Citation2010).

Medicinal uses and potential health benefits in modern medicine industry

Ginger extract can remove disorders caused by oxidative stresses as a strong anti-oxidant. Studies have shown that extant phenolic compounds and anthocyanins including gingerols and the sugevals had many neuro protective effects such as analgesic effects, memory improvement, and learning caused by the aging process (Fadaki et al. Citation2017). For culinary purposes ginger is suitable for all dished both sweet such as drinks, puddings, apple pie, cakes, breads, candies, etc; and savoury such as soups, sauces, stews, savoury puddings, grills, roasts, etc. (Oludoyin and Adegoke Citation2014). Oludoyin and Adegoke (Citation2014) stated that the active hypoglycaemic component of ginger was not affected by heat, hence, the consumption of ginger in raw and cooked forms in different cuisines maybe an effective regimen in the management of diabetes. Similarly, the medicinal uses of ginger are enormous such as exert anti-microbial, anti nausea (Portnoi et al. Citation2003), anti pyretic (Suekawa et al. Citation1984), analgesic, anti-inflammatory, hypoglycaemic (Ojewole Citation2006; Young et al. Citation2005), anti ulcer, antiemetic (Mascolo et al. Citation1989), cardio tonic, anti-hypertensive (Ghayur and Gilani Citation2005), hypolipidemic (Al-Amin et al. Citation2006), anti-platelet aggregation (Bordia et al. Citation1997) effects in both laboratory animals and human subjects. Turmeric is one of the main ingredients for curry powder, and used as an alternative to medicine and can be made into a drink to treat colds and stomach complaints (Chan et al. Citation2009). In folk medicine, turmeric has been used in lowering blood pressure and as tonic and blood purifier (The Wealth of India Citation2001). Phytochemical investigation of several types of ginger rhizomes has indicated the presence of bioactive compounds, such as gingerols, which are antibacterial agents and shogaols, phenylbutenoids, diarylheptanoids, flavanoids, diterpenoids, and sesquiterpenoids (Sivasothy et al. Citation2011; El Makawy et al. Citation2019). It has been proved in some researches that ginger leaves has great potential to be developed into functional foods and other health products, because it has higher antioxidant activity than rhizomes and flowers (Park et al. Citation2014). When compared to the Indian varieties, the Chinese ginger is low in pungency and is principally exported as preserves in sugar syrup or as sugar candy (Govindarajan Citation1982). Semwal et al. (Citation2015) reported that an infusion of ginger rhizomes with brown sugar is administered to relieve common colds, while scrambled eggs with powdered ginger is taken as a home remedy to reduce coughing in China. While, ginger is used in the United States as a remedy to alleviate motion sickness and morning sickness during pregnancy and to reduce hear cramps (Semwal et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, there are many studies that proved their beneficial effects against the symptoms of diseases, acting as anti-inflammatory, anti-tumour, anodyne, neuronal cell protective, anti-fungal and anti-bacterial agent (Mesomo et al. Citation2012; Yassen and Ibrahim Citation2016). Various ginger compounds and extracts have been tested as anti-inflammatory agents, where the length of the side chains determines the level of the effectiveness (Bartels et al. Citation2015). But, a combination of ginger extracts is more effective in decreasing inflammatory mediators than an individual compound (Lantz et al. Citation2007). The active ingredients in ginger are thought to reside in its volatile oils (Aldhebiani et al. Citation2017). The major ingredients in ginger oil are bisabolene, zingiberene, and zingiberol (Moghaddasi and Kashani Citation2012). Some other scientists noted that the interest in ginger is endorsed to its several biologically active compounds content such as gingerol, shogaols, gingerdiol, gingerdione, α-zingiberene, curcumin, and β-sesqui-phellandrene (Zhao et al. Citation2011). Ginger has been part of the folk medicine and popular nutraceuticals (Bartels et al. Citation2015). Ginger consists of a complex combination of biologically active constituents, of which compounds gingerols, shogoals and paradols reportedly account for the majority of its anti-cancer inflammatory properties (Tjendraputra et al. Citation2001). 6-paradol was suggested as a therapeutic agent to effectively protect the brain after cerebral ischemia, likely by attenuating neuroinflammation in microglia (Gaire et al. Citation2015). Zinger officinale used as a condiment in several countries but also it acts as a treatment for ailments; for instance, gastrointestinal disorders, colds, arthritis, hypertension and migraines (White Citation2007; Hosseini and Mirazi Citation2015). Maghbooli et al. (Citation2014) confirmed the efficiency of ginger powder in the therapy of common migraine attacks and its similarity to the antiepileptic drug. Many studies have reported that Ginger has useful effects to cancer prevention (Lee et al. Citation2008), also the treatment of nausea and vomiting due to pregnancy and chemotherapy (Pongrojpaw et al. Citation2007; Ryan et al. Citation2012). The anti-spasmodic effect of Ginger is due to the blocked of cyclooxygenase and 5-lipoxygenase (Van Breemen et al. Citation2011). Also, It has been reported that ginger lowers blood pressure through blockade of voltage-dependent calcium channels (Ghayur and Gilani Citation2005). Khaki et al. (Citation2012) reported that ginger has a protective effect against DNA damage induced by H2O2 and maybe promising in enhancing healthy sperm parameters. In Iran, traditionally ginger rhizome was used for enhancing male sexuality, regulating female menstrual cycle, and also reducing painful menstrual periods (Hafez Citation2010). Adib Rad et al. (Citation2018) reported that ginger as well as Novafen is effective in relieving pain in girls with primary dysmenorrhoea, and treatment with natural herbal medicine, non-synthetic drug, is recommended to reduce primary dysmenorrhoea. Karangiya et al. (Citation2016) concluded that the supplementation of garlic improves the performance of broilers when added at the rate of 1% of broiler and can be a viable alternative to antibiotic growth promoter in the feeding of broiler chicken. Manju and Nalini (Citation2010) found that ginger supplementation to 1,2-dimethyl hydrazine (DMH) treated rats inhibited colon carcinogenesis, as evidenced by the significantly decreased number and incidence of tumours; in addition ginger optimised tissue lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in DMH treated rats. Dinesh et al. (Citation2015) suggested that for growth promotion and management of soft rot disease in ginger, GRB35 B. amyloliquefaciens and GRB68 S. marcescens could be good alternatives to chemical measures; they also recommend the use of B. amyloliquefaciens for integration into nutrient and disease management schedules for ginger cultivation. Mahassni and Bukhari (Citation2019) found that the extract of ginger rhizome have different effects on cells and anti-bodies of the immune system in smokers and non-smokers, although both benefited from enhancement of the thyroid gland. In their research, it has been found that ginger maybe beneficial for smokers with anaemia, while for non-smokers, it may lead to a stronger antibody response or humoral immunity against infections. Vemuri et al. (Citation2017) found that aqueous natural extracts mixtures (NE mix) prepared from common spice like ginger is a potential alternative therapeutic approach in certain types of cancer. Bartels et al. (Citation2015) concluded that ginger maybe considered as a part of the symptomatic treatment of osteoarthritis (OA), where the patient is motivated for trying this nutraceutical. Schnitzer (Citation2002) mentioned that evidences is now provided suggesting that it may have a place in the management of OA of the knee, and coated ginger extract maybe considered for this purpose in the future. Adib Rad et al. (Citation2018) found that Ginger reduced menstrual pain, and it is effective in relieving pain in girls with primary dysmenorrhoea; moreover, Drozdov et al. (Citation2012) mentioned that Ginger is a safe drug with minimal side effects. Sinagra et al. (Citation2017) reported that ginger is an effective non-pharmacological option for treating hyperemesis gravidarum with respect to the inherent heterogeneity of the available studies. Gholampour et al. (Citation2017) found that ginger extract appears to exert protective effects against ferrous sulphate-induced hepatic and renal toxicity by reducing lipid peroxidation and chelating iron. Atashak et al. (Citation2014) mentioned that 10 weeks of either ginger supplementation or progressive resistance training (PRT) protects against oxidative stress and therefore both of these interventions can be beneficial for obese individuals. Jittiwat and Wattanathorn (Citation2012) demonstrated that ginger pharmacopuncture at GV20 can improve memory impairment following cerebal ischemia more rapidly than acupuncture, and one probable mechanism underlying this effect is improved oxidative stress. Yilmaz et al. (Citation2018) found the positive effects of ginger in folliculogenesis and implantation. They have also found that ginger may enhance implantation in rats in the long term with low dose. In other studies, the favourable outcomes have been reported on the positive effects of ginger on male infertility and sperm indices (Khaki et al. Citation2012; Ghlissi et al. Citation2013). Akinyemi et al. (Citation2016) described that dietary supplementation with both types of rhizomes, namely ginger and turmeric, inhibited arginase activity and prevented hypercholesterolaemia in rats that received a high-cholesterol diet. In conclusion, these activities of ginger represent possible mechanisms underlying its use in herbal medicine to treat several cardiovascular diseases. Amri and Touil-Boukoffa (Citation2016) concluded that Ginger has an important anti-hydatic effect in vitro, and this herbal product may protect against host,s cell death by reducing the high levels of nitric oxide (NO). They finally suggest the promising use of ginger in the treatment of Echinococcus granulosus infection. Soltani et al. (Citation2018) recommend administration of oral ginger one hour before operation to control the severity of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystetcomy. Daily et al. (Citation2015) claimed that ginger root supplementation significantly lowers blood glucose and HbA1c levels, and when combined with dietary and lifestyle interventions, it maybe an effective intervention for managing Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Islam et al. (Citation2014) boiled ginger extracts can be used in food preparation as well as against pathogenic bacteria during active infection. Viljoen et al. (Citation2014) suggested potential benefits of ginger in reducing nausea symptoms in pregnancy. They have found that ginger could be considered a harmless and possibly effective alternative option for women suffering from nausea and vomiting during pregnancy (NVP). Zaman et al. (Citation2014) mentioned that ginger root extract significantly inhibited the gastric damage and ginger root showed significant anti-ulcerogenic activity in the model studied, it can be a promising gastro-protective agent. Willetts et al. (Citation2003) concluded that ginger extract is a more effective treatment than placebo for nausea and retching during pregnancy. Yadav et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that ginger is one of the most commonly used spices and medicinal plants, and it is effective to improve diet-induced metabolic abnormalities, however the efficacy of ginger on the metabolic syndrome-associated kidney injury remains unknown. Naderi et al. (Citation2016) stated that ginger powder supplementation at a dose of 1 g/d can reduce inflammatory markers in patients with knee osteoarthritis, and it thus can be recommended as a suitable supplement for these patients. Mahmoud and Elnour (Citation2013) discovered that ginger has a great ability to reduce body weight without inhibiting pancreatic lipase level, or affecting bilirubin concentration, with positive effect on increasing peroxisomal catalase level and HDL-cholesterol. Ebrahimzadeh Attari et al. (Citation2015) revealed a minor beneficial effect of ginger powder supplementation on serum glucose and a moderate, significant effect on total cholesterol, as compared to the placebo. Malhotra and Singh (Citation2003) also mentioned the effect of ginger on lowering cholesterol, and anti-hyperlipidemic agent, the role of ginger in the treatment of nausea and vomiting (anti-emetic), ginger possesses anti-skin tumour promoting effects, and that the mechanism of such effects may involve inhibition of tumour promoter-caused cellular, biochemical, and molecular changes (Chemo-protective), anti-viral activity, anti-motion and anti-nauseant effects, anti-inflammatory, diminishing or eliminating the symptoms of hyperemesis gravidarum, ginger influence on exert abortive and prophylactic effects in migraine headache without any side effects and anti-ulcerogenic, Ginger and its constituent play pharmacological effects in cancer management via modulation of molecular mechanism, and the mechanism consist of Inhibition of VEGF, Activation of Bax, Inhibition of Lypoxygenase, Activation o P53, Inhibition of Interlukin, Inhibition of Bcl2 & Survivin, Inhibition of Cycloxygenase, Inhibition of IFN-γ, Suppression of TNF & NF-kB and Activation of G0/G1 phase (Rahmani et al. Citation2014). Accumulating evidence suggests that many dietary factors maybe used alone or in combination with traditional chemotherapeutic agents to prevent or treat disease, and ginger is example of medicinal plants which is gaining popularity amongst modern physicians (Sakr and Badawy Citation2011). Gagnier et al. (Citation2006) provide an excellent framework for the development of future trials that focus on providing satisfactory answers to issues relating to the efficacy of Z. officinale to ameliorate different types of pain, as well as, dosing strategies, treatment duration, safety, and cost effectiveness. The most important health benefits of ginger are shown in .

Table 5. The most important benefits of ginger.

Conclusion

Ginger is used worldwide as a cooking spice, condiment and herbal remedy, and it is also extensively consumed as a flavouring agent. Ginger, a plant in the Zingiberaceae family, is a culinary spice that has been as an important herb in Traditional Chinese Medicine for many centuries. More than 60 active constituents are known to be present in ginger, which have been broadly divided into volatile and non-volatile compounds. Hydrocarbons mostly monoterpenoid hydrocarbons and sesquiterpene include the volatile component of ginger and impart distinct aroma and taste to ginger. Nonvolatile compounds include gingerols, shogaols, paradols, and also zingerone. The active ingredients like gingerols, shogaols, zingerone, and so forth present in ginger exhibit antioxidant activity. Among gingerols and shogaol the major pungent components in the rhizome are 6-gingerol and 6-shogaol. Gingerol, the active constituent of ginger has been isolated and studied for pharmacological and toxic effects. Fresh ginger has been used for the treatment of nausea, cold-induced disease, colic, asthma, cough, heart palpitation, swellings, dyspepsia, loss of appetency and rheumatism. Medicinal properties associated with ginger are anti-inflammatory properties, anti-thrombotic properties, cholesterol-lowering properties, blood pressure-lowering properties, anti-microbial properties, anti-oxidant properties, anti-tumour properties, and hypoglycaemic properties. Consumption of ginger also has beneficial effects on heart disease, cancer, hypertension, obesity, diabetes, osteoarthritis, and bacterial infections. Ginger is an herbal, easily available, low price medication which is associated with low risk can be substituted for a chemical, scarce and expensive drugs. Based on other scientific literature, ginger demonstrates some promising health benefits, and more information gleaned from additional clinical studies will help confirm whether ginger,s multiple health benefits can be significantly realised in humans. Herbal remedies and other nutraceuticals are increasingly and extensively used by a substantial part of the population. To sum up, treatment with natural herbal medicine especially ginger, non-synthetic drug, is recommended.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Dr. Mohamad Hesam Shahrajabian, Senior Researcher at Biotechnology Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, People s Republic of China. Senior Researcher at Nitrogen Fixation Laboratory, Qi Institute, Building C4, No. 555 Chuangye, Jiaxing 314000, Zhejiang, People's Republic of China. Email: [email protected]

Dr. Wenli Sun, Research Assistant at Biotechnology Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, People's Republic of China. Senior Researcher at Nitrogen Fixation Laboratory, Qi Institute, Building C4, No. 555 Chuangye, Jiaxing 314000, Zhejiang, People's Republic of China. Email: [email protected]

Prof. Dr. Qi Cheng, Full Professor at Biotechnology Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, People's Republic of China. Senior Researcher at Nitrogen Fixation Laboratory, Qi Institute, Building C4, No. 555 Chuangye, Jiaxing 314000, Zhejiang, People's Republic of China. Email: [email protected]

References

- Adib Rad H, Basirat Z, Bakouei F, Moghadamnia AA, Khafri S, Farhadi Kotenaei Z, Nikpour M, Kazemi S. 2018. Effect of ginger and Novafen on menstrual pain: a cross-over trial. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 57:806–809. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2018.10.006

- Afzal M, Al-Hadidi D, Menon M, Pesek J, Dhami MS. 2001. Ginger: an ethno-medical, chemical and pharmacological review. Drug Metab Drug Interact. 18(3–4):159–190. doi: 10.1515/DMDI.2001.18.3-4.159

- Akinyemi AJ, Adedara IA, Thome GR, Morsch VM, Rovani MT, Mujica LKS, Duarte T, Duarte M, Oboh G, Schetinger MRC. 2015. Dietary supplementation of ginger and turmeric improves reproductive function in hypertensive male rats. Toxicol Rep. 2:1357–1366. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2015.10.001

- Akinyemi AJ, Oboh G, Ademiluyi AO, Boligon AA, Athayde ML. 2016. Effect of two ginger varieties on arginase activity in hypercholesterolemic rats. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 9(2):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2015.03.003

- Al-Amin ZM, Thomson M, Al-Qattan KK, Peltonen-Shalaby R, Ali M. 2006. Anti diabetic and hypoglycemic properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale) in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Br J Nutr. 96:660–666. doi: 10.1079/BJN20061849

- Aldhebiani AY, Elbeshehy EKF, Baeshen AA, Elbeaino T. 2017. Inhibitory activity of different medicinal extracts from Thuja leaves, ginger roots, Harmal seeds and turmeric rhizomes against Fig leaf mottle-associated virus 1 (FLMaV-1) infecting figs in Mecca region. Saudi J Biol Sci. 24:936–944. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.11.005

- Ali BH, Blunden G, Tanira MO, Nemmar A. 2008. Some phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe): a review of recent research. Food Chem Toxiology. 46(2):409–420. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.09.085

- Alakali J, Irtwange SV, Satimehin A. 2009. Moisture adsorption characteristics of ginger slices. Revista Ciência Technol Aliment. 29(1):155–164. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612009000100024

- Amri M, Touil-Boukoffa C. 2016. In vitro anti-hydatic and immunomodulatory effects of ginger and [6]-gingerol. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 9(8):749–756. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.06.013

- Atashak S, Peeri M, Azarbayjani MA, Stannard SR. 2014. Effects of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) supplementation and resistance training on some blood oxidative stress markers in obese men. J Exerc Sci Fit. 12:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jesf.2014.01.002

- Baliga MS, Haniadka R, Pereira MM, D’Souza JJ, Pallaty PL, Bhat HP, Popuri S. 2011. Update on the chemopreventive effects of ginger and its phytochemicals. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 51:499–523. doi: 10.1080/10408391003698669

- Bartels EM, Folmer VN, Bliddal H, Altman RD, Julh C, Tarp S, Zhang W, Christensen R. 2015. Review, efficacy and safety of ginger in osteoarthritis patients: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Osteoarthr Cartil. 23:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2014.09.024

- Blumenthal M, Goldberg A, Brinckmann J, editors. 2000. Herbal medicine: expanded Commission E monographs. Austin (TX): American Botanical Council; Newton (MA): Integrative Medicine Communications; p. 153–159.

- Bordia A, Verma SK, Srivastava KC. 1997. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) and fenugreek (Trigonella foenumgraecum L.) on blood lipids, blood sugar and platelet aggregation in patients with coronary artery disease. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 56(5):379–384. doi: 10.1016/S0952-3278(97)90587-1

- Chan EWC, Lim Y, Wong S. 2009. Effects of different drying methods on the antioxidant properties of leaves and tea of ginger species. Food Chem. 113:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.07.090

- Daily JW, Yang M, Kim DS, Park S. 2015. Efficacy of ginger for treating Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Ethn Food. 2:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jef.2015.02.007

- Dehghani I, Mostajeran A, Asghari G. 2011. In vitro and in vivo production of gingerols and zingiberene in ginger plant (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Iran J Pharm Sci. 7:129–133.

- Dhanik J, Arya N, Nand V. 2017. A review on Zingiber officinale. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 6(3):174–184.

- Dinesh R, Anandaraj M, Kumar A, Bini YK, Subila KP, Aravind R. 2015. Isolation, characterization, and evaluation of multi-trait plant growth promoting rhizobacteria for their growth promoting and disease suppressing effects on ginger. Microbiol Res. 173:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.01.014

- Drozdov VN, Kim VA, Tkachenko EV, Varvanina GG. 2012. Influence of a specific ginger combination on gastropathy conditions in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip. J Alternative Compl Med. 18(6):583–588. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0202

- Dugasani S, Pichika MR, Nadarajah VD, Balijepalli MK, Tandra S, Korlakunta JN. 2010. Comparative antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of [6]-gingerol, [8]-gingerol, [10]-gingerol and [6]-shogaol. J Ethnopharm. 2:525–520.

- Ebrahimzadeh Attari V, Mahluji S, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Ostadrahimi A. 2015. Effects of supplementation with ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) on serum glucose, lipid profile, and oxidative stress in obese women: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Pharmaceutical Sciences. 21:184–191. doi: 10.15171/PS.2015.35

- El Makawy AI, Ibrahim FM, Mabrouk DM, Ahmed KA, Ramadan MF. 2019. Effect of antiepileptic drug (Topiramate) and cold pressed ginger oil on testicular genes expression, sexual hormones and histopathological alterations in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 110:409–419. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.146

- El Sayed SM, Moustafa RA. 2016. Effect of combined administration of ginger and cinnamon on high fat diet induced hyperlipidemia in rats. J Pharm Chem Biol Sci. 3(4):561–572.

- Elzebroek ATG, Wind K. 2008. Guide to cultivated plants. Oxfordshire (UK): CAB International Wallingford; p. 276–279.

- Eric Chan WC, Lim YY, Wong SK. 2011. Antioxidant properties of ginger leaves: an overview. Free Radic Res. 1:6–16.

- Fadaki F, Modaresi M, Sajjadian I. 2017. The effects of ginger extract and diazepam on anxiety reduction in animal model. Indian J Pharm Educ Res. 51(3):S159–S162. doi: 10.5530/ijper.51.3s.4

- Gagnier JJ, Boon H, Rochon P, Barnes J, Moher D, Bombardier CB. 2006. Reporting randomized, controlled trials of herbal interventions: an elaborated CONSORT statement. Ann Intern Med. 155(5):364–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-5-200603070-00013

- Gaire BP, Kwon OW, Park SH, Chun KH, Kim SY, Shin DY, Choi JW. 2015. Neuroprotective effect of 6-paradol in focal cerebral ischemia involves the attenuation of neuroinflammatory responses in activated microglia. PLoS One. 10(3):e0120203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120203

- Gaur M, Das A, Sahoo RK, Mohanty S, Joshi RK, Subudhi E. 2016. Comparative transcriptome analysis of ginger variety Suprabha from two different agro-climatic zones of Odisha. Genom Data. 9:42–43. doi: 10.1016/j.gdata.2016.06.014

- Ghayur MN, Gilani AH. 2005. Ginger lowers blood pressure through blockade of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 45:74–80. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200501000-00013

- Ghayur MN, Gilani AH, Afridi MB. 2005. Cardiovascular effects of ginger aqueous extract and its phenolic constituents are medicated through multiple pathways. Vascul Pharmacol. 43:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2005.07.003

- Ghlissi Z, Atheymen R, Boujbiha MA, Sahnoun Z, Makni Ayedi F, Zeghal K, El Feki A, Hakim A. 2013. Antioxidant and androgenic effects of dietary ginger on reproductive function of male diabetic rats. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 64:974–978. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2013.812618

- Gholampour F, Behzadi Ghiasabadi F, Owji SM, Vatanparast J. 2017. The protective effect of hydroalcoholic extract of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc.) against iron-induced functional and histological damages in rat liver and kidney. Avicenna J Phytomed. 7(6):542–553.

- Govindarajan VS. 1982. Ginger-chemistry, technology, and quality evaluation: part 1. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 17:1–96. doi: 10.1080/10408398209527343

- Grant KL, Lutz RB. 2000. Ginger. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 57:945–947. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/57.10.945

- Grzanna R, Lindmark L, Frondoza CG. 2005. Ginger – an herbal medicinal product with broad anti-inflammatory actions. J Med Food. 8(2):125–132. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2005.8.125

- Hafez DA. 2010. Effect of extracts of ginger roots and cinnamon bark on fertility of male diabetic rats. J Am Sci. 6:940–947.

- Hasanah M, Sukarman, Rusmin D. 2004. Ginger seed production technology. Technol Dev Spices Med. 16(1):9–16.

- Hosseini A, Mirazi N. 2015. Alteration of pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure threshold by chronic administration of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extract in male mice. Pharm Biol. 53:752–757. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.942789

- Islam K, Rowsni AA, Khan MM, Kabir MS. 2014. Antimicrobial activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts against food-borne pathogenic bacteria. International Journal of science. Environ Technol. 3(3):867–871.

- Jittiwat J, Wattanathorn J. 2012. Ginger pharmacopuncture improves cognitive impairment and oxidative stress following cerebral ischemia. J Acupunct Meridian Stud. 5(6):295–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2012.09.003

- Kala C, Ali SS, Chaudhary S. 2016. Comparative pharmacognostical evaluation of Costus speciosus (Wild ginger) and Zingiber officinale (ginger) rhizome. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 8(4):19–23. doi: 10.22159/ijcpr.2016v8i4.15270

- Karangiya VK, Savsani HH, Patil SS, Garg DD, Murthy KS, Ribadiya NK, Vekariya SJ. 2016. Effect of dietary supplementation of garlic, ginger and their combination on feed intake, growth performance and economics in commercial broilers. Vet World. 9(3):245–250. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2016.245-250

- Kathi JK. 1999. Ginger (Zingiber officinale). The Longwood Herbal Task Force (http://www.mcp.edu/herbal/default.htm) and The Centre for Holistic Pediatric Education and Research (http://www.childrenshospital.org/holistic/).

- Keys JD. 1985. Chinese herbs. 3rd edn. Japan: Charles E Tuttle Company, Inc; p. 77–78.

- Khaki A, Farnam A, Badie AD, Nikniaz H. 2012. Effects of onion (Allium cepa) and ginger (Zingiber officinale) on sexual behaviour of rat after inducing antiepileptic drug (Lamotrigine). Balkan Med J. 29:236–242.

- Kim SO, Kundu JK, Shin YK, Park JH, Cho MH, Kim TY, Surh YJ. 2005. [6]-gingerol inhibits COX-2 expression by blocking the activation of p38 MAP kinase and NF-kappaB in phorbol ester-stimulated mouse skin. Oncogene. 15:2558–2567. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208446

- Kochhar A. 1981. Tropical crops. A textbook of economic botany. London: McMillan Press. p. 268–270.

- Kundu JK, Surh YJ. 2009. Molecular basis of chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals: redox-regulated transcription factors as relevant targets. Phytochem. Rev. 2:333–347. doi: 10.1007/s11101-009-9132-x

- Langner E, Greifenberg S, Gruenwald J. 1998. Ginger: history and Use. Advances in Ther. Jan/Feb. 15(1):25–44.

- Lantz RC, Chen GJ, Sarihan M, Solyom AM, Jolad SD, Timmermann BN. 2007. The effect of extracts from ginger rhizome on inflammatory mediator production. Phytomedicine. 14(2–3):123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.03.003

- Lee SH, Cekanova M, Baek SJ. 2008. Multiple mechanisms are involved in 6-gingerol-induced cell growth arrest and apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 47(3):197–208. doi: 10.1002/mc.20374

- Lister M. 2003. Herbal medicine in pregnancy. Complement Nurs Midwifery. 9(1):49. doi: 10.1016/S1353-6117(02)00129-4

- Maghbooli M, Golipour F, Esfandabadi MA, Yousefi M. 2014. Comparison between the efficacy of ginger and sumatriptan in the ablative treatment of the common migraine. Phytother Res. 28:412–415. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4996

- Mahassni SH, Bukhari OA. 2019. Beneficial effects of an aqueous ginger extract on the immune system cells and antibodies, hematology, and thyroid hormones in male smokers and non-smokers. J Nutr Intermediary Metab. 15:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jnim.2018.10.001

- Mahmoud RH, Elnour WA. 2013. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of ginger and orlistat on obesity management, pancreatic lipase and liver peroxisomal catalase enzyme in male albino rats. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 17:75–83.

- Malhotra S, Singh AP. 2003. Medicinal properties of ginger (Zingiber officinale Rosc). Nat Prod Radiance. 2(6):296–301.

- Manju V, Nalini N. 2010. Effect of ginger on lipid peroxidation and antioxidant status in 1,2-dimethyl hydrazine induced experimental colon carcinogenesis. J Biochem Tech. 2(2):161–167.

- Mascolo N, Jain R, Jain SC, Capasso F. 1989. Ethno pharmacologic investigation of ginger (Zingiber officinale). J Ethnopharmacol. 7:129–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(89)90085-8

- Melati IS, Palupi ER, Susila AD. 2016. Growth, yield and quality of ginger from produced through early senescence. Int J Appl Sci Technol. 6(1):21–28.

- Memudu AE, Akinrinade ID, Ogundele OM, Duru F. 2012. Investigation of the androgenic activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) on the histology of the testis of adult sparague dawley rats. J Med Med Sci. 3(11):697–702.

- Mesomo MC, Scheer AP, Elisa P, Ndiaye PM, Corazza ML. 2012. Ginger (Zingiber officinale R.) extracts obtained using supercritical CO2 and compressed propane: kinetics and antioxidant activity evaluation. J Supercrit Fluids. 71:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2012.08.001

- Mishra RK, Kumar A, Kumar A. 2012. Pharmacological activity of Zingiber officinale. Int J Pharm Chem Sci. 1(3):1422–1427.

- Moghaddasi MS, Kashani HH. 2012. Ginger (Zingiber officinale): a review. J Med Plants Res. 6(26):4255–4258.

- Naderi Z, Mozaffari-Khosravi H, Dehghan A, Nadjarzadeh A, Fallah Huseini H. 2016. Effect of ginger powder supplementation on nitric oxide and C-reactive protein in elderly knee osteoarthritis patients: A 12-week double-blind randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Tradit Complement Med. 6:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.12.007

- Niksokhan M, Hedarieh N, Maryam N, Masoomeh N. 2014. Effect of hydro-alcholic extract of Pimpinella anisum seed on anxiety in male rat. J Gorgan Uni Med Sci. 16(4):28–33.

- Nour AH, Yap SS, Nour AH. 2017. Extraction and chemical compositions of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) essential oils as cockroaches repellent. Aust J Basic Appl Sci. 11(3):1–8.

- Ogbaji PO, Li J, Xue X, Shahrajabian MH, Egrinya EA. 2018. Impact of bio-fertilizer or nutrient solution on Spinach (Spinacea Oleracea) growth and yield in some province soils of P.R. China. Cercetari Agron Moldova. 2(174):43–52. doi: 10.2478/cerce-2018-0015

- Ojewole JAO. 2006. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory and hypoglycemic effects of ethanol extract of Zingiber officinale (Roscoe) rhizomes in mice and rats. Phytother Res. 20:764–772. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1952

- Oludoyin AP, Adegoke SR. 2014. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale) extracts on blood glucose in normal and streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Int J Clin Nutr. 2(2):32–35.

- Palatty PL, Haniadka R, Valder B, Arora R, Baliga MS. 2013. Ginger in the prevention of nausea and vomiting: a review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 53(7):659–669. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.553751

- Park GH, Park JH, Song HM, Eo HJ, Kim MK, Lee JW, Lee MH, Cho KH, Lee JR, Cho HJ, et al. 2014. Anti-cancer activity of ginger (Zingiber officinale) leaf through the expression of activating transcription factor 3 in human colorectal cancer cells. BMC Complement Altern Med. 14:408. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-408

- Peter KV. 2000. Handbook of herbs and spices. Cambridge: RC Press Wood Head Publishing; p. 319.

- Pongrojpaw D, Somprasit C, Chanthasenanont A. 2007. A randomized comparison of ginger and dimenhydrinate in the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. J Med Assoc Thailand Chotmaihet Thangphaet. 90(9):1703–1709.

- Portnoi G, Chng LA, Karimi-Tabesh L, Koren G, Tan MP, Einarson A. 2003. Prospective comparative study of the safety and effectiveness of ginger for the treatment of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynaecol. 189:1374–1377. doi: 10.1067/S0002-9378(03)00649-5

- Rahmani AH, Al Shabrmi FM, Aly SM. 2014. Active ingredients of ginger as potential candidates in the prevention and treatment of diseases via modulation of biological activities. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol. 6(2):125–136.

- Ryan JL, Heckler CE, Roscoe JA, Dakhil SR, Kirshner J, Flynn PJ, Hickok JT, Morrow GR. 2012. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) reduces acute chemotherapy-induced nausea: a URCCCCOP study of 576 patients. Support Care Cancer. 20(7):1479–1489. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1236-3

- Sakr SA, Badawy GM. 2011. Effect of ginger (Zingiber officinale R.) on metiram-inhibited spermatogenesis and induced apoptosis in albino mice. J Appl Pharm Sci. 01(04):131–136.

- Sandeep S. 2017. Commentary on therapeutic role of ginger (Zingiber officinale) as Medicine for the Whole world. Int J Pharmacogn Chin Med. 1(1):1–3.

- Schnitzer TK. 2002. American College of Rheumatology Update of ACR guidelines for osteoarthritis: role of the coxibs. J Pain Symptom Manage. 23:524–530. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(02)00372-X

- Schwertner HA, Rios DC. 2007. High-performance liquid chromatographic analysis of 6-gingerol, 8-gingerol, 10-gingerol, and 6-shogaol in ginger containing dietary supplements, spices, teas, and beverages. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 856:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.05.011

- Sekiwa Y, Kubota K, Kobayashi A. 2000. Isolation of novel glycosides from ginger and their antioxidative activity. J Agric Food Chem. 8:373–379. doi: 10.1021/jf990674x

- Semwal RB, Semwal DK, Combrinck S, Viljoen AM. 2015. Gingerols and shogaols: important nutraceutical principles from ginger. Phytochemistry. 117:554–568. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2015.07.012

- Shahrajabian MH, Wenli S, Qi C. 2018. A review of Goji berry (Lycium barbarum) in traditional Chinese medicine as a promising organic superfood and superfruit in modern industry. Acad J Med Plants. 6(12):437–445.

- Sharma Y. 2017. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) – an elixir of life a review. Pharma Innov J. 6(10):22–27.

- Shirin Adel PR, Prakash J. 2010. Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of ginger root (Zingiber officinale). JMPR. 4(23):2674–2679.

- Sinagra E, Matrone R, Gullo G, Catacchio R, Renda E, Tardino S, Miceli V, Rossi F, Tomasello G, Raimondo D. 2017. Clinical efficacy of ginger plus B6 vitamin in hyperemesis gravidarum: report of two cases. Gastroenterol Hepatol Open Access. 6(1):00182. DOI: 10.15406/ghoa.2017.06.00182.

- Singh RP, Gangadharappa HV, Mruthunjaya K. 2017. Ginger: a potential neutraceutical. An updated review. Int J Pharmacogn Phytochem Res. 9(9):1227–1238.

- Sivasothy Y, Wong KC, Hamid A, Eldeen IM, Sulaiman SF, Awang K. 2011. Essential oil of Zingiber officinale var. rubrum Theilade and their antibacterial activities. J Food Chem. 124(2):514–517. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.06.062

- Soltani E, Jangjoo A, Afzal Aghaei M, Dalili A. 2018. Effects of preoperative administration of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) on postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Tradit Complement Med. 8:387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.06.008

- Suekawa M, Ishige A, Yuansa K, Sudo K, Aburada M, Hosoya E. 1984. Pharmacological studies on ginger pharmacological actions of pungent constituents of 6-gingerol and 6-shogaol. J. Pharmacoblodyn. 7:836–848. doi: 10.1248/bpb1978.7.836

- Surh YJ, Loe E, Lee JM. 1998. Chemopreventive properties of some pungent ingredients present in red pepper and giner. Mutant Res. 402:259–267. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00305-9

- Tan BKH, Vanitha J. 2004. Immunomodulatory and antibacterial effects of some Traditional Chinese medicinal herbs: A Review. Curr Med Chem. 11(11):1423–1430. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365161

- The Wealth of India. 2001. A dictionary of Indian raw materials and industrial products. New Delhi: National Institute of Science Communication, CSIR, p. 264–293 . (First supplement series vol. II).

- Tjendraputra E, Tran VH, Liu-Brennan D, Roufogalis BD, Duke CC. 2001. Effect of ginger constituents and synthetic analogues on cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme in intact cells. Bioorg Chem. 29(3):156–163. doi: 10.1006/bioo.2001.1208

- Toda K, Hitoe S, Takeda S, Shimoda H. 2016. Black ginger extract increases physical fitness performance and muscular endurance by improving inflammation and energy metabolism. Heliyon. 2: Article No-e00115. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2016.e00115

- Ursell A. 2000. The complete guide to healing foods. London: Dorling Kindersley Ltd; p. 112–114.

- USDA. 2013. National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Release 26 Full Report (All Nutrients) Nutrient data for 2013, Spices, Ginger.

- Van Breemen RB, Tao Y, Li W. 2011. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in ginger (Zingiber officinale). Fitoterapia. 82(1):38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2010.09.004

- Vasala PA. 2004. Ginger. In Peter KV, editor. Handbook of herbs and spices. Vol. 1. Cochin (India); p. 640.

- Vemuri SK, Banala RR, Subbaiah GPV, Srivastava SK, Reddy AVG, Malarvili T. 2017. Anti-cancer potential of a mix of natural extracts of turmeric, ginger and garlic: a cell-based study. Egypt J Basic Appl Sci. 4:332–344. doi: 10.1016/j.ejbas.2017.07.005

- Viljoen E, Visser J, Koen N, Musekiwa A. 2014. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect and safety of ginger in the treatment of pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting. Nutr J. 13(20):1–14.

- Wei CK, Tsai YH, Korinek M, Hung PH, El-Shazly M, Cheng YB, Wu YC, Hsieh TJ, Chang FR. 2017. 6-Paradol and 6-shogaol, the pungent compounds of ginger, promote glucose utilization in adipocytes and myotubes, and 6-paradol reduces blood glucose in high-fat diet-fed mice. Int J Mol Sci. 18(1):168. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010168

- White B. 2007. Ginger: an overview. Am Family Phys. 75:1689–1691.

- Willetts K, Ekangaki A, Eden JA. 2003. Effect of a ginger extract on pregnancy-induced nausea: a randomised controlled trial. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 43:139–144. doi: 10.1046/j.0004-8666.2003.00039.x

- Wynn SG, Luna SPL, Liu H. 2001. Global acupuncture research: previously untranslated studies. Studies from Brazil. In: Schoen AM, editor. Veterinary acupuncture: ancient art to modern medicine. St Louis (MO): Mosby; p. 53–57.

- Yadav S, Sharma PK, Aftab Alam M. 2016. Ginger medicinal and uses and benefits. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 3(7):127–135.

- Yassen D, Ibrahim AE. 2016. Antibacterial activity of crude extracts of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) on Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus: a study in vitro. Indo Am J Pharm Res. 6(06):5830–5835.

- Yilmaz N, Seven B, Timur H, Yorganci A, Inal HA, Kalem MN, Kalem Z, Han O, Bilezikci B. 2018. Ginger (zingiber officinale) might improve female fertility: a rat model. J Chin Med Assoc. 81:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2017.12.009

- Young HV, Luo YL, Chang HY, Haieh WC, Liao JC, Peng WC. 2005. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of 6-gingerol. J. Ethnopharmacol. 96:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.09.009

- Zaman SU, Mirje MM, Ramabhimaiah S. 2014. Evaluation of the anti-ulcerogenic effect of Zingiber officinale (ginger) root in rats. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 3(1):347–354.

- Zhao X, Zingiber B, Yang WR, Yang Y, Wang S, Jiang Z, Zhang GG. 2011. Effects of ginger root (Zingiber officinale) on laying performance and antioxidant status of laying hens and on dietary oxidation stability. Poult Sci. 90:1720–1727. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-01280

- Zick SM, Ruffin MT, Djuric Z, Normolle D, Brenner DE. 2010. Quantitation of 6-,8- and 10-gingerols and 6-shogaol in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection. Int J Biomed Sci. 6(3):233–240.