Abstract

This paper investigates how subfields within translation studies have been defined and how research interests and foci have shifted over the years, using data from the Translation Studies Abstracts (TSA) online database. We draw on the notions of ‘landscape’ and ‘sketch maps’ in an attempt to reflect on the role that TSA editors, as well as writers of papers and abstracts, have had on the dynamics of the field. We start by offering an overview of the contents of the database, and reflect on how bibliographical tools ultimately represent partial views of a disciplinary landscape. We look at how different bibliographies devise categories for describing topics of research and thus create maps to navigate that landscape. However, maps are static devices, unable to represent how the landscape was shaped historically. Thus, we also use a TSA corpus to observe how classifications and the frequencies of keywords have changed at different points in time, while reflecting on how, as inhabitants of this landscape, editors of bibliographies affect the extent to which the data is both representative of and informed by the field, and as colonizers, they impose their order upon it.

Landscape and inhabitants: Existing bibliographies and issues of representativeness

Translation Studies Abstracts (TSA)Footnote1 is an online database that now replaces the eponymous yearly journal first published in printed form in 1998 by St Jerome together with its companion volume, the Bibliography of Translation Studies. The print journals co-existed along with the database from 2003 until 2009, when the printed publication was discontinued. TSA contains over 16,000 complete entries, including abstracts of articles, chapters and dissertations in the field of translation studies, as well as brief summaries of book-length publications, and is maintained and edited by the authors of this paper. Each entry includes standard bibliographic data: author(s)/editor(s), date and place of publication, page numbers (for articles) or total number of pages (for books), ISSN/ISBN number, title (including an English translation of titles in languages other than English), journal volume and issue, and URL for online publications. Abstracts have always been a required field of any entry, although this policy is currently under consideration. Optional additional information includes keywords, tables of contents, editorial comments, reference lists and so on. Furthermore, each item is assigned to one or more broad subject-area categories, usually not more than three.

While the first of its kind, TSA was quickly followed by BITRAFootnote2 and TSB,Footnote3 two other translation studies specific bibliographies important to mention here as the two other main sources of bibliographical studies in the field, including those by Franco Aixelá (Citation2004, Citation2010, 2013) and van Doorslaer (Citation2007). BITRA (Bibliografía de Interpretación y Traducción) is a database established in 2001 by Franco Aixelá at the University of Alicante and, at the time of writing, holds the largest number of records (over 55,000), about one third of which contain an abstract (Franco Aixelá, Citation2010, p. 152). As well as other methods to ensure comprehensiveness, the editors of BITRA regularly check lists of references for new items and, based on their observation that they are increasingly finding fewer items to add, Franco Aixelá claims that the database is ‘sufficiently representative’ (Franco Aixelá, Citation2010, p. 152). The Translation Studies Bibliography, started in 2004 by the publisher John Benjamins and edited by Yves Gambier and Luc van Doorslaer, contains over 24,000 records, which are, according to the website, ‘annotated’, although not necessarily with a full abstract.

While we might expect that the larger the database the more representative it will be, it is not possible to establish to what extent any of them adequately represents the academic production in the field, particularly in terms of total output, type of publication and language of publication. In what follows, we offer a preliminary quantification of TSA contents along those parameters and reflect on the possible biases that bibliographical tools may reflect depending on the way they have been set up.

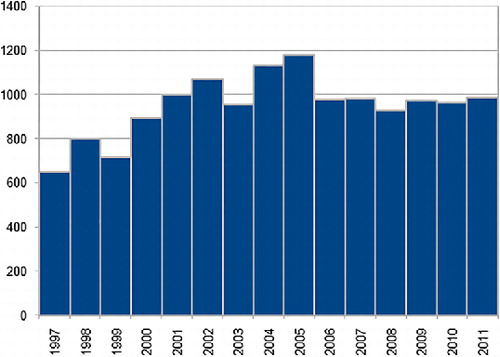

Franco Aixelá, Orero and Rovira-Esteva (Citation2013) claim that over 40,000 publications have been issued in the field of translation studies in the last 20 years, which suggests an average of 2,000 items per year. In 2013, TSA contained over 14,200 abstracts for the 15 years between 1997 and 2011, that is, about 950 abstracts on average per year.Footnote4 According to this estimate, then, TSA includes about half of all items published in this time span. A graphic representation of the annual distribution of the total number of abstracts during those years () seems to indicate a trend, whereby the total number of abstracts increases steadily, almost doubling in the 9 years from 1997 to 2005, after which time the annual number decreases approximately 17% and then remains steady. The initial increase can probably be explained by the fact that it became progressively easier to collect abstracts available in electronic format. It is also to be expected that some years may be more productive than others in terms of data entry, although productivity is not necessarily linked to year of publication given that abstracts are also entered retrospectively. The incline of the graph might thus be interpreted as a surge, which peaks in 2005 but which overall follows a positive trend, though the rate and causes of increase cannot be clearly established.

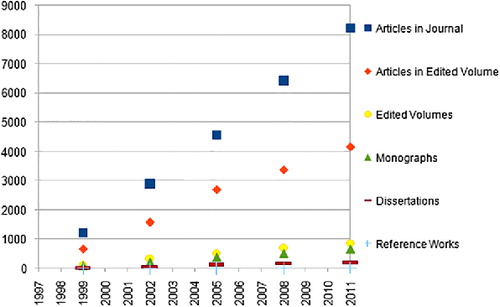

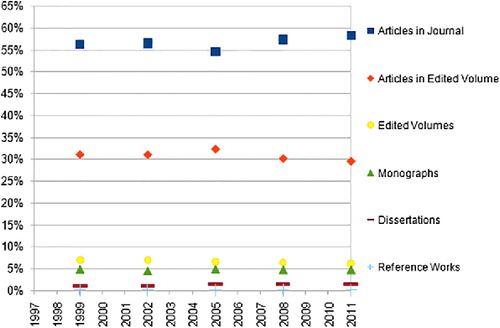

In terms of genre, this total number includes abstracts for about 8,700 journal articles, 4,300 articles in edited volumes, 1,000 edited volumes, 900 monographs, 200 dissertations and a few dozen reference works. presents the cumulative number of entries for each type, showing that there has been a steady progression in the number of publications across all types. shows the same data represented as percentages of each type per year, thus representing the relative weight, or salience, of each type of abstract and indicates, for example, that in 2011 the percentage of abstracts of journal articles is slightly higher than in 2005 while that of articles in collected volumes is slightly lower. This more nuanced picture suggests that while the share of each abstract type has been more or less stable, there has been a small decrease in the number of monographs and edited volumes relative to the percentage share of articles, particularly in relation to journal articles. While books have remained an important format for reporting substantive research pieces, it appears that there has been an increase in the number and accessibility of journals across Translation Studies, which is reflected in these figures.

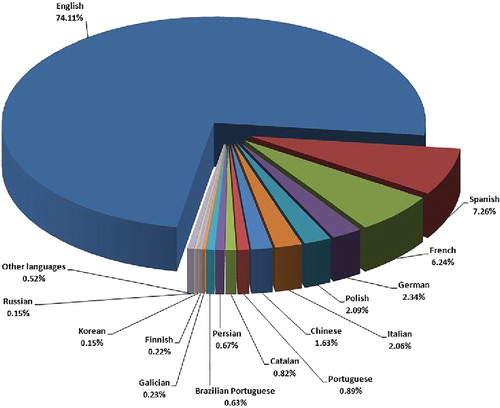

While TSA is essentially an Anglophone database, publishing English abstracts of works originally published in English – a group that makes up almost three-quarters of the total number of entries – it also includes abstracts in English of works written in 31 other languages. Spanish is the best represented of these, followed by French (see ) and together with works written originally in German, Polish, Italian and Chinese make up more than 95% of TSA's total number of entries. This suggests that there is a bias in terms of language and, by implication, place of publication. This might be accounted for by the simple fact that it is easier to find or write an abstract in English of an article originally written in English than it is to find, write or translate an abstract of an article originally written in another language.

At the same time, the disproportionate representation of languages in TSA could reflect a bias in the abstracts themselves, in that many of the major journals in the field are published in Europe (although the database is regularly updated with abstracts from select Chinese and Brazilian journals). The relative importance that certain journals have at different points in time can also affect the balance of languages represented.Footnote5 Other sources of bias are likely to be the more or less proactive attitude of journal and book editors, book authors and publishers in terms of marketing and contributing entries themselves. However, the most important acknowledgement to make regarding the languages represented in TSA is that they undoubtedly reflect a bias in the editors’ professional networks and consequent accessibility to publications. Franco Aixelá (Citation2004, Citation2010, p. 153) points to a possible bias in BITRA caused by the fact that it is mainly a personal project by a Spanish lecturer in English translation, so that English and Spanish texts are bound to be over-represented. In TSA, the working languages and affiliations of contributors and users are also likely to have an effect, as is the fact that the publisher (St Jerome for the period under analysis) was based in the United Kingdom.

This point concerning the subjectivity of the data collected in TSA is important to the methodological and theoretical framework adopted in this paper. Bibliographies are tools that help us plan our research by enabling scholars to trace what has been done previously with regards to topics, texts and contexts, and thus helping us expand our horizons. At the same time, they impose limitations since no bibliography is absolutely comprehensive. As a manually updated database (as opposed to automatic internet-based searches such as Google Scholar) TSA is both targeted to capture abstracts particular to the field of translation studies but also fraught with inconsistencies and fluctuations of human behavior. Bibliographies provide a way of surveying the past; we must, however, be aware of possible distortions created by the fact that the concepts and categories we use have been shaped by the same history that we want to trace. In order to integrate this awareness and bring an element of self-reflexivity to this bibliographic study, we draw from anthropological work by Arjun Appadurai and Tim Ingold so as to discuss translation studies as a disciplinary landscape (Appadurai, Citation1996) and acknowledge our role, as editors of TSA and authors of this paper, as inhabitants in that landscape (Ingold, Citation2007). Kershaw and Saldanha (Citation2013) propose the use of the landscape metaphor for developing new ways of theorizing the contexts of production and reception of translation. Here, we would like to suggest that the discipline of translation studies can also be conceived as a landscape. Bibliographies such as TSA, BITRA and BTS provide entry points into and paths across such landscapes, thus affecting the way in which the landscape is viewed and explored.

In Lines: A Brief History, Tim Ingold (Citation2007) examines the changing relationship between writing and musical notation, and concludes that the fundamental changes triggering the eventual distinction between language and music lie in changing perceptions of the line – all notation consists of lines – and its relationship to surface. The ways in which lines are understood, argues Ingold, ‘depend critically on whether the plain surface was compared to a landscape to be travelled or a space to be colonized’ (Citation2007, p. 39). In Modernity at Large. Cultural dimensions of globalization, Arjun Appadurai (Citation1996) also uses the concept of landscape and, in particular the suffix -scape, to reflect the fact that the ways in which we conceptualize cultural, political, economic and social spaces are fluid, and depend on the angle of vision; they are ‘deeply perspectival constructs, inflected by the historical, linguistic, and political situatedness of different sorts of actors’ (Citation1996, p. 33). The landscape of translation studies has changed considerably in the last decades and those changes are viewed differently according to the position of the actors. What is more, as editors of bibliographies and academics working the land, we do not just present different views but inevitably leave traces, and open up channels that facilitate certain travels routes at the expense of others.

In terms of travelling a landscape, Ingold describes two modalities: wayfaring and transport: ‘The wayfarer is continuously on the move’ (Citation2007, p. 75) and has to sustain him/herself ‘both perceptually and materially, through an active engagement with the country that opens up along his [or her] path’ (Citation2007, p. 76). Transport, on the other hand, is ‘destination-oriented. It is not so much a development along a way of life as a carrying across, from location to location, of people and goods in such a way as to leave their basic natures unaffected’ (Citation2007, p. 77). Of the two, wayfaring, argues Ingold:

[I]s the most fundamental mode by which living beings, both human and non-human, inhabit the earth. By habitation I do not mean taking one's place in a world that has been prepared in advance for the populations that arrive to reside there. The inhabitant is rather one who participates from within in the very process of the world's continual coming into being and who, in laying a trail of life, contributes to its weave and texture. These lines are typically winding and irregular, yet comprehensively entangled into a close-knit tissue. (Citation2007, p. 81)

Wayfarers integrate knowledge along a path of travel. This differs from the dominant framework of modern thought, according to which ‘knowledge is assembled by joining up, into a complete picture, observations taken from a number of fixed points’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 88). As editors of TSA, we integrate knowledge about the discipline and into the discipline as we work on the database. We cannot deny that the methods we use in this paper are designed on the modern assumption that observations taken from a number of points will build a complete picture (i.e. by the dominant framework of modern thought). However, we endeavor to reflect on our participation in the making of the landscape of translation studies and stress that the picture presented in this paper is nothing more than a sketch map that reflects our own positions in the field and that of previous TSA editors.

Ingold claims that with the advent of print, and under the sway of modernity, the line has been fragmented into a succession of points. This fragmentation reflects another that took place in the ‘related fields of travel, where wayfaring is replaced by destination-oriented transport, mapping, where the drawn sketch is replaced by the route-plan, and textuality, where storytelling is replaced by the pre-composed plot’ (Citation2007, p. 75). One way in which scholars occupy or ‘colonise’ (Citation2007, p. 39) a field of knowledge is by fragmenting it and creating taxonomies and maps that divide the field into separate units. This is part and parcel of all systems developed to organize and consult bibliographies, as we discuss below.

Occupying the field: Categories, keywords and descriptors

A thematic classification may be obtained through a controlled (i.e. closed) system of categories, such as the thematic descriptors or keywords used by BITRA (Franco Aixelá, Citation2004).Footnote6 There are 12 main descriptors (corresponding to: interpreting, author, work, profession, pedagogy, machine translation, history, genre, problem, research, theory), and a single entry may be classified according to more than one descriptor. Most of these descriptors are subdivided once or even twice into more specific labels designating, for example, modes of interpreting, periods in history, types of problems and well-known theories and theoretical topics. These categories are applied to each entry by editors on the basis of titles, keywords and – when provided by authors – abstracts. In addition to this controlled system of descriptors, there is also an open field for themes (Franco Aixelá, Citation2010, p. 152), which can include more specific descriptions, languages, and so on. Franco Aixelá (Citation2010, p. 156) clearly states that BITRA's classification does not pretend to be either exact or objective, and given the lack of consensus on the metatheoretical terminology in any field of humanities, acknowledges that other editors are likely to have classified the same publications differently.

Because TSA first appeared as a bi-annual print journal with the annual Bibliography of Translation Studies (BTS) as a companion, TSA categories were first drawn up (between the editors and the publisher) to ease readers’ consultation of the abstracts in printed format. Each abstract was assigned to one category only, and the journal was divided into sections that reflected these categories. Abstracts were cross-referenced at the end of each section and in the author, title and keywords indexes. A keyword index was included so that readers could search for specific topics (such as ‘metaphor’, ‘news’ or ‘indirect translation’) within and across categories. The index was created by the editors on the basis of a list of all the keywords associated with each abstract, which was then synthesized for consistency and ease of reference.

The list of categories for TSA and BTS was modified and amended in 2004 when the two publications were merged, and again between 2005 and 2007, in preparation for the new online platform, which allows abstracts to be assigned to more than one category.Footnote7 The changes in categories required reassigning existing abstracts to new categories, a time consuming endeavor, which explains why there were not more revisions. While the abstracts are entered by a large number of contributors,Footnote8 the categories have always been assigned (or supervised) by a restricted number of people.Footnote9 Without an exacting coding process, however, the classification of abstracts depends on the subjective interpretation of the categories and the contents of each abstract by this restricted group. Thus, the classifications will reflect changes in the editorial team, as well as the editors’ changing perceptions as to the various categories and contents of the abstracts and database.

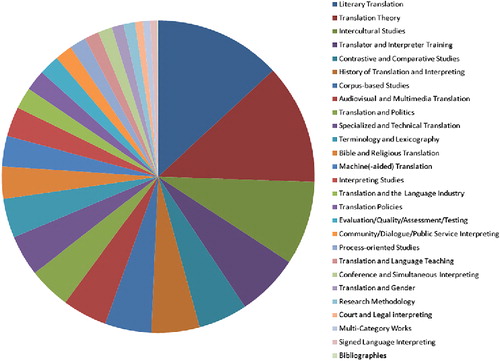

There are currently 27 categories and presents a snapshot of the relative proportion of each one. As can be seen, about one third of all abstracts were assigned to at least one of the first three most numerous categories: ‘literary translation’, ‘translation theory’ and ‘intercultural studies’.

As mentioned above, bibliographies create entry points into the disciplinary landscape and thus facilitate certain travels routes, often at the expense of others. The organizational principle underlying John Benjamins’ TSB goes a step further in terms of ‘colonizing the space’ to use Ingold's words (Citation2007, p. 23) since, from the very beginning, the Editorial BoardFootnote10 ‘explicitly aimed at establishing a structuring principle in the inherent conceptual complexity of the keywords system of the bibliography’ (van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 219). A decision was made to integrate (most of) the keywords used by authors into a conceptual map, adopting the Holmes/Toury Translation Studies map as a prototype. This responds, in the view of the TSB editorial board, to ‘an urgent need for a systematizing tool’ which was perceived as missing from translation studies from the very beginning of its history (van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 218). While acknowledging that replicating authors’ keywords would result in some advantages, such as ‘terminological creativity, conceptual multiplicity and renewal of the discipline’, TSB editors decided not to rely on the keywords already appended to the articles because of ‘how inaccurate keywords can be, with their unnecessary overlaps, unclear division of levels etc.’ (van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 221) and the resulting ‘ambiguities, confusion and idiosyncrasies’ (van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 220), which would threaten the terminological or conceptual uniformity of the field.

As a result, TSB offers a larger and more complex system of categories than either BITRA or TSA. To give just one example, described in van Doorslaer (Citation2007), the editors of TSB realized that many of the keywords referred to translation as a product and a process rather than to the theoretical meta-discourse around translation. As a result, they decided to introduce a basic distinction between the two; the resulting map has two head keywords, ‘translation studies’ and ‘translation’, linked by a dotted line which ‘indicates a ‘special’ relationship of a sort of complementariness, possibly internecessity, but no hierarchy, no inclusion etc.’ (van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 222).

Ingold argues that in drawing maps we are attempting to colonize a space, but he also makes an important distinction between two different types of maps: sketch and cartographic. We could argue that a list of categories presents a sketch map, one which ‘consists – no more and no less – of the lines that make it up’ and ‘makes no claim to represent a certain territory, or to mark the spatial locations of features included within its frontiers’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 84). The more structure is added to the map, however, the more it resembles modern cartographic maps, which not only have ‘borders separating the space inside, which is part of the map, from the space outside, which is not’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 85) but also lines representing roads, and railways, as well as administrative boundaries. The lines drawn across the surface of the cartographic map ‘signify occupation, not habitation. They betoken as appropriation of the space surrounding the points that the lines connect or – if they are frontier lines – that they enclose’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 85). We could argue that the lists of categories or descriptors used in TSA and BITRA constitute sketch maps, while the conceptual map created for TSB is closer to a cartographic map.

From hierarchies to mapping the landscape

The categories in TSA make up a non-hierarchical system of classification, and are simply listed on the database interface in alphabetical order. There is no doubt that such lists are overly simplistic and, although there is no deliberate attempt to delimit a certain territory, even these sort of sketch maps impose artificial boundaries, concealing certain de facto hierarchies while revealing others. For example, unlike BITRA, TSA does not contain ‘interpreting’ as part of its title. ‘Interpreting studies’ appears as a category, which suggests that it could be interpreted as a subfield within the discipline of translation studies. In fact, this seems to be the default approach in all three bibliographies: BITRA includes ‘interpreting’ as a descriptor and ‘translation studies’ is used as an umbrella term in TSB, covering both translation and interpreting studies while ‘translation’ covers both translation and interpreting. The umbrella function of the ‘translation’ category is most clearly apparent in the TSB conceptual map, mentioned above, which, to some extent, attempts to redress the status difference by creating another level in which Translation Studies and Interpreting Studies (and ‘translation’ and ‘interpreting’) stand side by side.

Other hidden hierarchies can be found in the fact that while there is a general ‘research methodology’ category in TSA, there are also specific categories for ‘corpus-based studies’, ‘process-oriented studies’ and ‘contrastive and comparative studies’, but not for, say, ‘ethnographic studies’. The classification in BITRA seems to suffer from the same bias; under the descriptor ‘research’, we find only one sub-category, ‘corpus’.

BITRA is more explicitly hierarchical than TSA in that it clearly subdivides descriptors into subdescriptors. Hierarchical levels impose further constraints in terms of delimiting categories, which may also conceal and reveal various connections. BITRA's hierarchical structure subsumes, for example, ‘metaphor’ under ‘problem’. However, the metaphorics of translation is a whole area of research (see, for example, St André, Citation2010) that deals with theoretical conceptualizations that are far removed and have little to do with the problems created by the use of metaphors in, say, the translation of poetry or academic papers.

While we could argue that flat classifications and hierarchies do, to some extent, reflect the frequency of keywords and title words used by the authors and contributors themselves, there is no denying that the editors, in selecting categories to classify abstracts, also fulfill a legitimizing role, controlling the ways in which the discipline evolves and channeling the journeys undertaken by users of the bibliographies. As Pym notes, maps have a powerful way of making you ‘look in certain directions’ and ‘overlook other directions’ (Citation1998, p. 3); the Holmes/Toury map, he argues, does not have a unified area for the historical study of translation, while having a specific category for ‘time-restricted theoretical studies’ (Citation1998, p. 2). Van Doorslaer (Citation2007) laments the fact that first attempts at mapping and systematizing the discipline, such as those made by Nida, Holmes and Toury, have been ‘strikingly few in number’ (Citation2007, p. 220), resulting in what Wilss calls ‘a virtual supermarket of reflections and ideas’ (as cited in van Doorslaer, Citation2007, p. 219). He goes on to suggest that the dearth of attempts to map the field may have been a response to Pym's (Citation1998) severe criticism of mapping as an over-simplistic and over-hierarchical instrument that delimits any field of study. Pym notes that:

[a] facile way to overcome this fragmentation is to claim that all the categories are interrelated dialectally. You are supposed to add or imagine little arrows all over the place. Is this a real solution? If arrows really do go from all points to all other points, who would need the map in the first place? Maps name consecrated plots and the easiest routes between them. (Citation1998, p. 2)

Interestingly, maps also efface memory: ‘[h]ad it not been for the journeys of travellers, and the knowledge they brought back, it could not have been made. The map itself, however, bears no testimony to these journeys’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 24). Maps create the illusion that they reflect a pre-existing territory; they are static. As the field changes as the result of competing forces and events over which scholars have various degrees of control – often rather minimal – new maps are needed to re-charter the territory. This is what the editors of TSB have tried to do with their dynamic map that is designed to evolve with the discipline. However, maps (and charts, graphs, and other visual representations) are two dimensional, and either depth (proportion), or (change over) time, or surface (comprehensiveness) is often sacrificed in the interests of the two dimensions we choose to represent.

One way in which we can use bibliographies to remind us of the journeys undertaken by its inhabitants and how these have changed the landscape is by interrogating the data to examine how different subfields of translation have developed. This adds a layer of depth to the data by considering how, at different stages in the evolution of the discipline, certain areas tend to be trodden more often by scholars in the field, sometimes opening up new avenues of investigation.

Categories across time

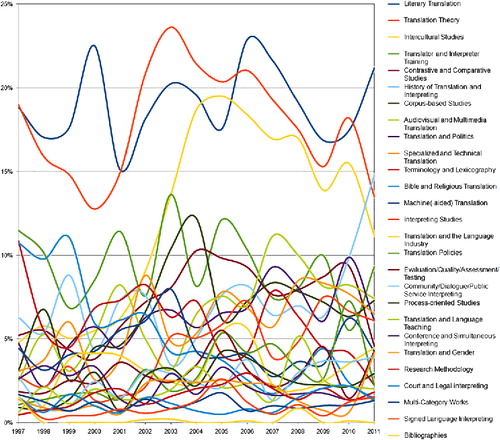

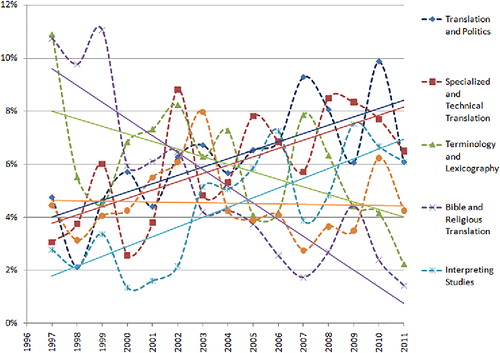

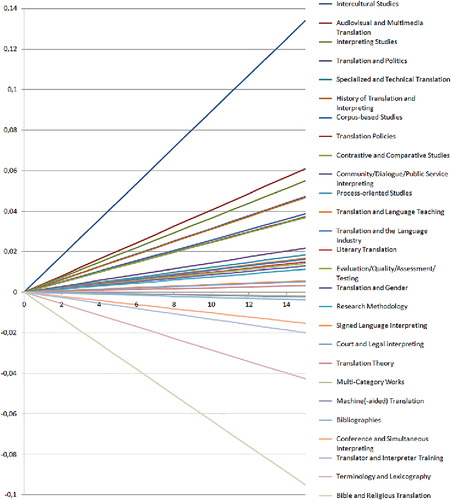

In order to offer a historical perspective, we now turn to the number of abstracts assigned to each of the 27 categories in TSA () and how they have changed over time. We view this data not only as a way of assessing the relative attention garnered by different areas of research across the life of the database but also as a way of reflecting on how TSA categories both reflect and distort the overall picture presented. represents the trends followed by all of the TSA categories. We can observe that the way in which the lines criss-cross each other reflects how even lines representing an artificial fragmentation are ‘winding and irregular’, to use Ingold's way of referring to inhabitant's wayfaring through the landscape quoted above. Furthermore, if we bear in mind the fact that the categories represented by each line have grey borders often overlapping with one another we can imagine how a more detailed graphical representation would show how these categories, rather than representing separate threads, actually become ‘entangled into a close-knit tissue’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 81).

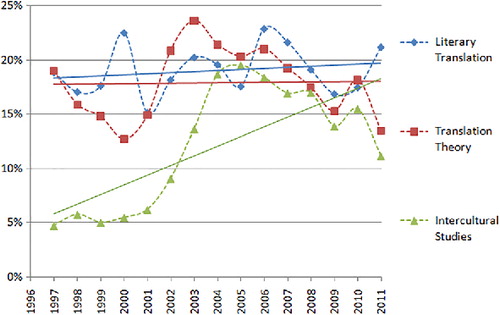

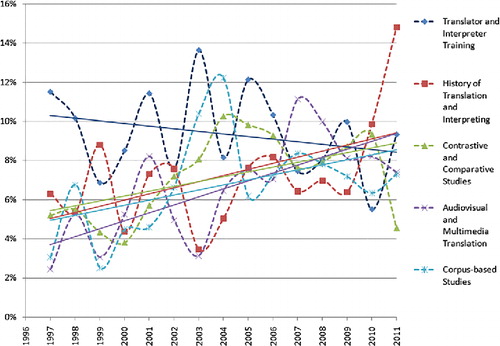

The problem with comprehensive and detailed graphs such as is that they do not allow us to spot patterns easily, so we need to resort to zooming-in lenses to observe some lines in more detail. , and include the most populated categories subdivided into three groups. tracks the three categories with the highest proportion of abstracts: literary translation, intercultural studies and translation theory; tracks the next five largest categories (with 1000–1500 abstracts) and the next five (with 500–1,000 abstracts).

As shown in , literary translation and translation theory together represent 25% of all abstracts. The dotted lines in show the yearly change in percentages (of total number of abstracts) for each category, while the straight lines indicate overall trends. While it is true that there may be some overlap between these two categories (literary translation and translation theory), it is also true that the overlap extends to other categories as well; it may thus be fair to presume that one factor compensates the other. It would be interesting to further pursue this investigation by looking at how many abstracts classified as literary translation are also classified in other categories, and which ones, and so on for all categories. For the time being, we can say that these two categories were in 1997 and still are the most dominant areas of research within translation studies. They present a stable trend, with a slight predominance of literary translation over translation theory. Intercultural studies (9% of all abstracts) is a less dominant category but, notably, shows a positive trend in the fifteen years surveyed, with a sharp increase between 2001 and 2005 (at which point all three categories were at similar levels), followed by a gradual overall decrease. This trajectory can be partly explained by the change in policy allowing the selection of more than one category for each abstract that accompanied the shift from print publication. By facilitating the assignment of multiple categories to the same abstract, the ‘comprehensive’ categories such as these first three are favoured over more ‘specialized’ categories, such as court and legal interpreting, in that they will more often be co-selected. However, it can also be said that intercultural studies has been increasingly perceived as a relevant category in translation studies research.

The second group () includes the next five largest categories: translator and interpreter training, history of translation and interpreting, comparative and contrastive studies, audiovisual and multimedia translation, and corpus-based translation studies, all containing between 1000 and 1500 abstracts each. Although there is much criss-crossing over a limited range, some trends are discernible, such as the growth of audiovisual and multimedia translation and the decline of translator and interpreter trainer as a research category.

A third group () includes categories in the range of 500 to 1,000 abstracts: Bible and religious translation, interpreting studies, machine (-aided) translation, translation and politics, specialized and technical translation, terminology and lexicography. Again some trends are visible: machine (-aided) translation is fairly stable over time, whereas the remaining categories are notably in either ascent or descent. Translation and politics, specialized and technical translation and interpreting studies have come to play an increasingly important role, while Bible and religious translation and terminology and lexicology have shrunk their percentage share. According to TSA, scientific and technical translation has grown an average of 6% since 1998, which confirms the trend observed by Franco Aixelá (Citation2004).

goes one step further in terms of simplifying the trajectories of each category and offers an overview of the relative increase, decrease or stability of numbers of abstracts for each category.

The reflexive comments in existing bibliographic studies (van Doorslaer, Citation2007; Franco Aixelá, Citation2004, Citation2010, Citation2013) suggest that editors of bibliographies are very aware of the difficulties and effects of assigning abstracts to categories. Some categories end up being marginal (in TSA, for example, ‘translation policy’ is rarely used) while others cover sub-categories that are so diverse in terms of the relative number of articles they represent that it is difficult to appreciate what the overall categories consists of: What percentage does drama translation represent in ‘literary translation’? Or interpreter trainer in ‘translator and interpreter training’? Some categories are more likely to be shared categories (‘corpus-based studies’ is often combined with ‘literary translation’ or ‘translator and interpreter training’), while other, more specific categories (Bible and religious translation, court interpreting, signed language) are less likely to be shared. In order to offer a first, albeit rough, assessment of the degree to which TSA categories actually represent the contents of TSA, we decided to extract a list of keywords from the abstracts themselves by converting the contents of TSA into a corpus and using frequency lists of word types and noun phrases. So, in the next section, instead of looking at the categories designated by TSA editors, we present the same picture from a different angle of vision, one that attempts to draw more directly from contributors’ and authors’ choices.

Categories versus corpus-derived keywords

The corpus of TSA abstracts contains only the titles and the body of the abstracts (i.e. no author, keywords, language, etc.). Overall, the corpus contains over 2 million words (2,028,458) and over 16,000 abstracts, and the average length of each abstract is 125 words. The first stage of the analysis involved looking at word lists. The aim was to take a step back from our subjective position of editors and look at the percentage of usage of certain terms by the authors of the articles and abstracts themselves.

shows a simple frequency list of content words in the TSA corpus that has, as could be expected, ‘translation’ at the top (function words like ‘the’, ‘of’, ‘and’, ‘in’, ‘to’ were filtered out). The second column is a list of ‘keywords’ as understood in corpus linguistics, that is, words that are significantly more frequent in this corpus as compared to a frequency list based on a larger reference corpus. The keywords listed were extracted after loading the TSA corpus into the Sketch Engine corpus compiling application and using the EnTenTen08 corpus as a reference corpus.Footnote11 These lists are revealing in that they confirm the overall bias that we predicted in terms of the dominant position of English and of studies on literary translation. The significant impact on the discipline of the cultural turn and the rise of corpus-based methods are reflected in the fact that both ‘cultural’ and ‘corpus’ are keywords. The presence of keywords such as ‘language/s’, ‘text/s’, ‘linguistics’ and ‘discourse’ might reflect the fact that text-based analysis has been the default in terms of research methods.

Table 1. Most common content words and keywords in the TSA corpus.

shows a list of the first 50 key noun-phrases automatically extracted from the corpus by using as a reference a key noun phrase list extracted from a 40 million word corpus provided by the Sketch Engine.Footnote12 This rough and ready ‘terminology list’ opens several potentially interesting lines of enquiry. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on the overlap of categories between the list of categories devised by the editors of TSA and the terms emerging as keywords from the titles and abstracts themselves (which, worth repeating here, do not include the list of keywords optionally associated with the entry).

Table 2. Key noun-phrases in the TSA corpus.Footnote13

Concerning the overlap between TSA-assigned categories, we note that 21 of the key noun phrases in correspond to one of the 27 TSA categories. In fact, practically all the terms that do not reflect the typical phraseology of academic abstracts (such as ‘research project’, ‘first part’, ‘second part’) or are typical of the description of translations (‘source text’, ‘target language’, etc.) correspond to categories in the database and/or are clearly related to them. These terms are highlighted in bold in . From the perspective of the existing categories (see ), 15 of the TSA-assigned categories can be said to be represented in . We could consider this as evidence that the categories selected by the editors are doing a reasonable job in terms of covering the areas of specialization within the field. However, a potentially more fruitful exercise is to question the degree of matching and the partial correspondence in some cases.

Table 3. Correspondence between TSA categories and key terms suggested by the TSA corpus.

As was to be expected, classifications such as ‘bibliographies’ or ‘multi-category works’ are not represented among the key terms suggested by the TSA corpus. Umbrella categories such as ‘interpreting studies’ or ‘research methodology’ might also be expected to lack strong matches in terms of the phraseology actually used in abstracts. Terms such as ‘Bible’, ‘religious translation’, ‘terminology’, ‘lexicography’, ‘gender’, ‘politics’, ‘policies’ and those referring to different types of interpreting are quite specific and, even despite their relative importance as topics in the translation studies field, they will always represent a minority in relation to broader categories such as ‘theory’, ‘research’, ‘intercultural’, etc. The fact that they do not appear as key noun phrases (in ) could also be due to the fact that some of them are likely to be very common terms in the reference corpus. In fact, if we look beyond the first 100 keywords (i.e. at a longer list than the one included in ) in the corpus, we note that the relevance of ‘terminology’, which appears ranked 39 (keyness score 5.1) in the list of keywords, is further reinforced by the appearance of ‘terminology management’ as a key noun phrase ranked 150 (keyness score: 1.2), together with several related noun phrases with the same keyness score of 1.1 (‘legal terminology’, ‘terminology work’ ‘medical terminology’, ‘terminological knowledge’ and ‘terminology extraction’).

Looking at the results in from the perspective of the key noun phrases suggested by the corpus, we find that terms such as ‘translator competence’, ‘legal translation’, ‘case study’, ‘descriptive translation’, ‘cultural translation’ and ‘translation criticism’ are particularly interesting because, although they can be subsumed under broader TSA categories, they may also suggest that a revision of category labels is needed in order to reflect more accurately the language used by contributors and authors. We may want to question, for example, whether the label ‘competence’ should not be appended to ‘translators and interpreter training’ since it may be used in other contexts, such as in studies where a professional translator's practice is compared to that of a trainee translator's, which would not necessarily fit under the category of ‘training’. Likewise, we may question the wisdom of having ‘assessment’ and ‘testing’ instead of ‘criticism’ associated with ‘quality’. The field of ‘legal translation’ arguably deserves its own label, separate from that of ‘technical and specialized translation’, not because legal texts are a particularly distinctive genre as compared to, for example, scientific articles, but simply because it has attracted more attention from translation studies scholars. On the same basis, the labels ‘case study’ and ‘descriptive translation’ (the latter being accounted for by the common use in the field of ‘descriptive translation studies’ to refer to methodological choices) could warrant their own classifications as research methodologies. The term ‘cultural translation’ presents an interesting challenge in that it could be assumed that those abstracts would be placed under the ‘intercultural studies’ category but its salience may again suggest the need for a new category. This exercise could be further extended to the key terms ranked 51 to 100, where we find further reinforcement for the existing categories (comparative analysis, audio description, translation training, translation memory, corpus-based study, quality assessment, to mention but a few) as well a few key noun phrases that might be worth considering as candidates for categories (lingua franca; translation strategy, cultural identity).

Keywords over time

The results and discussion presented in the previous two sections attempted to add a layer of depth to the two dimensional views presented by lists and maps (as discussed in the first two sections) by taking into account change over time (in terms of how the number of abstracts assigned to categories evolved) as well as proportional representation (both in terms of editor-made categories and corpus-derived key words) and comprehensibility (by comparing the editor-made categories with the corpus-derived key words). In this section, we look at how corpus-derived keywords (as opposed to editor-made categories) evolved over time so as to look at the temporal dimension from a different (again, less editor-centred) perspective. The KeyWords feature in WordSmith Tools (Scott, Citation2008) was used to compute keywords (as understood in corpus linguistics) for each year. This time we used as a reference corpus all other abstracts in the corpus before that year, to indicate the ‘new trends’ identified per year (see ). Thus, for the year 1997, the reference corpus is all abstracts up to 1996, and corpus/corpora and related words seem to be a new trend in that year. For some years some negative keywords are listed. These are words that are notably less frequent than in previous years. Because this part of the analysis is restricted to the TSA corpus, we have lost the objectivizing perspective provided by using a corpus of general English as a reference. We look at changes in the discourse of translation scholars without comparing it to language used in other settings. Again, we find that new categories suggest themselves, such as: ethics, localization, news translation, and advertising. Ethics is clearly a matter of increasing importance and one that would not necessarily fit into existing categories. The case of localization is interesting because it demonstrate that the ‘controlling’ efforts made by editors of bibliographies are not always successful. The category ‘translation and the language industry’ was introduced to encompass articles on localization as well as related activities such as web translation, language planning, crowdsourcing, software development, multilingual documents production and professional issues. However, ‘localization’ specifically came to be one of the most important areas of growth in translation studies and the use of this particular term would probably be more useful as an entry point. News translation could, in principle, be subsumed within technical and specialized translation; however, it looks as if, together with ‘legal translation’, it has attracted enough attention to warrant a separate category. This raises another question concerning the length and heterogeneity of the list: to what extent can we keep adding categories for specific text-types? There will always be hybrid genres and text-types that do not comfortably fit any of those; general categories will always be needed. Advertising is another interesting term in this regard: it cannot be subsumed easily into the category of technical and specialized communication because one of its defining characteristics is its multimodal quality, which brings it closer to audiovisual and multimedia translation.

Table 4. New trends in TSA corpus: keywords over time.

Conclusion

Borrowing Ingold's words (Citation2007, p. 89) quoted above, it is fundamentally through the practices of wayfaring that researchers inhabit a disciplinary landscape. Researchers integrate knowledge along a path of travel, following the contours of a land made up of the existing literature, which are affected by a range of changes in the environment, including their own traces. It is useful, at certain points during our journey, to stop and take stock. One way of doing so is to create conceptual maps. However, following Ingold, we could argue that conceptual maps, like cartographic ones, conform to ‘a powerful impulse in modern thought to equate the march of progress, whether of culture or civilization, with the increasing domination of an unruly – and therefore non-linear – nature’ (Citation2007, p. 155). The alternative we suggest here is to draw sketch maps. In cartographic maps, lines are connectors between places, in sketch maps, the lines retrace the journeys made and the views opened in the process (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 87). These maps should not be seen as ‘steps in the march of progress’ but as ‘successive vistas that open up along the way towards a goal’ (Ingold, Citation2007, p. 238).

Here we have attempted to sketch the landscape of translation studies starting from different points of departure: the categories drawn up by TSA editors, key words and key noun phrases obtained from using TSA abstracts as a corpus compared with a general English reference corpus, and key words obtained by comparing the abstracts entered in one particular year with those in the rest of TSA. The results confirm trends that translation studies scholars have already highlighted as well as less predictable ones. The predominant role played by literary translation has not been negatively impacted by the increased attention paid to other genres (audiovisual, multimedia and multimodal translation – including localization and news translation; legal documents and specialized texts in general). ‘Translator and interpreter training’, ‘Terminology and lexicography’ and ‘Bible and religious translation’ seem to be relatively in the decline, but are still important categories. The cultural turn of the 1980s has been consolidated by an increasing interconnection between translation and intercultural studies, reflected not only in the growth of publications in those areas but also in the areas of concerns addressed within the discipline in the last two decades (such as advertising, ethics, censorship, humor, news, multimedia and multimodal translation, politics, psychoanalysis). Research on translation history represents another increasingly strong and growing area of research. In terms of methodologies, the impact of linguistic corpora is noticeable and is a trend that is clearly here to stay.

The categories representing areas of research in our maps, whether cartographic or sketch ones, are attempts at recognizing significant places in the landscapes. However, they are not self-contained and stable areas of knowledge or activity. Ingold suggests that one

prominent casualty of the fragmentation of lines of movement, knowledge and description (…), and of their compression into confined spots, has been the concept of place. Once a moment of rest along a path of movement, place has been reconfigured in modernity as a nexus within which all life, growth and activity are contained. Between places, so conceived, there are only connections. (Citation2007, p. 96)

Our categories represent conjunctions where the traffic along different lines of enquiry has gathered enough momentum to become a discernable node but, as the results presented here show, this node keeps changing shape, expanding or shrinking, due to the fact that traffic along the lines crisscrossing at that particular point may increase or decrease, as well as shift in different directions. For our lines of enquiry to change significantly, research methods need to change along with the nature of the object under study. We can hypothesize, for example, that the increased attention to ethics and agency is linked to the use of social research methods (such as interviews), as well as psychoanalysis (Freud) and ethnography as methodological tools in the last few years. However, fractures and disjunctures can result from differing paces of development in terms of the accessibility of certain objects of study and the developments of tools that facilitate their observation. The availability of new methods enables new perspectives; corpus-analysis, for example, seems to have furthered empirical research whether of historical material or of news translation. On the other hand, while multimodal translation (whether of advertising, web pages, software or films) is clearly attracting increasing attention, most obviously influenced by the technological advances that have enabled the increased accessibility, circulation and study of multimodal material, there is little indication that methods have changed in order to cater for the increased complexity of empirical research in these cases. It is precisely these faultiness as well as new crossroads and fertile areas that a reflective and critical use of bibliographies help us identify.

Biographical notes

Federico Zanettin is Associate Professor of English Language and Translation at the University of Perugia, Italy. His research interests range from comics in translation, to corpus-based translation studies and intercultural communication. His publications include the volumes Translation-Driven Corpora (2012), Comics in Translations (2008, editor), Corpora in Translator Education (2003, co-editor), and articles in various journals and edited volumes. He is co-editor of the online translation studies journal inTRAlinea.

Gabriela Saldanha is a Lecturer in Translation Studies at the University of Birmingham, UK. She has published extensively on translation stylistics and her current research interests include transcultural reading and the marketing and reception of translations, with a focus on Brazilian literature published in the Anglophone world. She is co-editor of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Translation Studies (Routledge, 2009), together with Mona Baker; of Research Methodologies in Translation (St Jerome, 2013) together with Sharon O’Brien, and of a special issue on ‘Global Landscapes of Translation’ (Translation Studies, 2013) together with Angela Kershaw.

Sue-Ann Harding is Assistant Professor at the Translation and Interpreting Institute of Hamad bin Khalifa University, Doha, under the auspices of Qatar Foundation. Her research interests are in the areas of translation and social-narrative theory (extended to complexity theory), media representations and configurations of violent conflict, and explorations of intralingual and intersemiotic translation with regards to collective memory and issues of state, (national) identity, civil society and social justice. She is the author of Beslan: Six Stories of the Siege (Manchester University Press, 2012) and several articles in leading translation studies journals. Sue-Ann is currently the Reviews Editor for The Translator and interim Chair of the IATIS Executive Council.

Notes

1. Translation Studies Abstracts https://www.stjerome.co.uk/tsa/ (accessed 8 June 2014).

2. Bibliografía de Interpretación y Traducción http://dti.ua.es/es/bitra/introduccion.html (accessed 8 June 2014).

3. Translation Studies Bibliography https://benjamins.com/online/tsb/ (accessed 8 June 2014).

4. 1998 was the publication date of the first TSA print volume, which included works published in 1997 and, to a lesser extent, 1996. Abstracts of titles published before 1997 were collected and added to the database at a later date and, because of the emphasis on collecting new data, are fewer and included less consistently. Data after 2011 are not included because they were still being collected in 2013, the time period during which our analyzes were conducted.

5. Franco Aixelá (Citation2004) notes that Meta – a multilingual journal which, nevertheless, has French as its first language – is responsible for the anomalous situation created between 1966 and 1990 regarding language distribution in BITRA, with a much higher presence of French in technical translation than in any other field.

6. In his 2010 publication, Franco Aixelá uses the Spanish descriptores temáticos and often refers to themes (or temas) when referring to the classification system used in BITRA. Here we have tried to keep as close as possible to the author's own choice of words.

7. Modifications and amendments included removing category subdivisions, aligning the category lists for each publication, which were initially different, refining or broadening categories and adding a category (Translation and Politics) to reflect the increasing number of articles on that topic.

8. In addition to TSA editors, contributors include authors, editors of journals and collected volumes and individuals who contribute in return for access to the database.

9. These include the current editors (and authors of this article) and previous and contributing editors (eight people in all).

10. Consisting in those first years of Franco Aixelá, Yves Gambier, Daniel Gile, José Lambert, Gideon Toury and Luc van Doorslaer.

11. TenTen is a new generation of Web corpora available in a range of languages, which are preloaded in the Sketch Engine and made available as reference corpora (Kilgarriff, Rychly, Smrz and Tugwell, Citation2004/2007; Kilgarriff, Citation2012); EnTenTen08 is a 3 billion English corpus, which is provided as a default reference corpus by the system.

12. This is a sample of the EnTenTen12 corpus annotated with a term grammar.

13. The numbers in brackets represent the keyness score. For the formula used, see http://www.sketchengine.co.uk/documentation/raw-attachment/wiki/SkE/DocsIndex/ske-stat.pdf (accessed 17 June 2014).

References

- Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large. Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- van Doorslaer, L. (2007). Risking conceptual maps: Mapping as a keywords-related tool underlying the online Translation Studies Bibliography. Target, 19(2), 217–233. doi:10.1075/target.19.2.04van

- Franco Aixelá, J. (2004). The study of technical and scientific translation: an examination of its historical development. Jostrans, 1. Retrieved from http://www.jostrans.org/issue01/art_aixela.php

- Franco Aixelá, J. (2010). Una revisión de la bibliografía sobre traducción e interpretación médica recogida en BITRA (Bibliografía de Interpretación y Traducción). [An overview of the bibliography related to medical translation and interpreting as collected in BITRA (Bibliography of Interpreting and Translation)]. Panacea. Boletín de Medicina y Traducción, XI(32), 151–160. Retrieved from http://www.tremedica.org/panacea/IndiceGeneral/n32_tribuna_aixela2.pdf

- Franco Aixelá, J. (2013). Who's who and what's what in Translation Studies: A preliminary approach. In C. Way, S. Vandepitte, R. Meylaerts & M. Bartłomiejczyk (Eds.), Tracks and Treks in Translation Studies: Selected papers from the EST Congress, Leuven 2010 (pp. 7–28). Amsterdam & Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Franco Aixelá, J., Orero, P. & Rovira-Esteva, S. (2013). Call for papers: Perspectives: Studies in Translatology. Retrieved from http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/cfp/rmpscfp.pdf

- Ingold, T. (2007). Lines: A Brief History. Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

- Kershaw, A., & Saldanha, G. (2013). Introduction: Global landscapes of Translation. Translation Studies, 6(2), 135–149. doi:10.1080/14781700.2013.777257

- Kilgarriff, A., Rychly, P., Smrz, P., & Tugwell, D. (2004/2007). The Sketch Engine. In Proceedings of Euralex. In Hanks, (Ed.), Lexicology: Critical concepts in Linguistics (pp. 105–116). London: Routledge.

- Kilgarriff, A. (2012). Getting to know your corpus. In Sojka, P., Horak, A., Kopecek, I., Pala K. (Eds). Proc. Text, Speech, Dialogue (TSD 2012), Lecture notes in Computer Science. (pp. 3–15). New York & Berlin: Springer.

- Pym, A. (1998). Method in translation History. Manchester: St. Jerome.

- Scott, M. (2008). WordSmith tools version 5. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software.

- St. Andre, J. (2010). Thinking through translation with Metaphors. Manchester: St Jerome.