ABSTRACT

The focus of this article is placed on dubbing intonation and more specifically on the tonal patterns that are regularly found in dubbed speech and characterise prefabricated orality at tone level. Research suggests that dubbed dialogue is governed by its own network of rules and differs greatly from spontaneous and naturally-occurring speech. The prefabricated nature of this type of dialogue has received attention from many scholars, but no attempt has been made to date to describe orality at tone level from an empirical perspective. The aim of this paper is to search for regularities in the delivery of dubbing intonation in a Spanish corpus and to explore whether they can have an impact on the reception of orality by the Spanish audience. A speech analysis programme has been used to examine a repertoire of tones in a number of extracts from the Spanish dubbed version of the sitcom How I met your mother (Bays & Thomas, 2005–2014). Findings reveal that there are several prefabricated patterns that belong to dubbing intonation itself and that some of the dominant trends found could directly impinge on the target audience’s perception.

1. Introduction

The language of dubbing has been categorised as ‘una terza norma’ (a third norm), mainly because it repeats established linguistic patterns that do not belong to the source language nor do they belong to the target language, but to dubbing itself (Pavesi, Citation1996, p. 128). This type of dialogue, which follows ‘its own rules and norms’ (Bucaria, Citation2008, p. 162) and imitates spontaneous speech, is not as spontaneous as should be expected and is prefabricated in nature (Baños, Citation2014; Baños-Piñero & Chaume, Citation2009; Chaume, Citation2004, Citation2012), as it has been conceived as a written text but needs to give the impression of an ad-lib orality while hiding its elaborated, written origin. Brutti and Zanotti (Citation2012) have described it as a language that, despite departing from spontaneous orality, ‘tends to a normalized, homogeneous neo-standard’ (p. 172), what could explain why dubbed dialogue is credited by many as sounding contrived, stilted, and somewhat artificial.

The prefabricated nature of dubbed speech has awakened the interest of a number of scholars, who have traditionally focused on the verbal rendering of dubbed prefabricated orality. According to Pérez-González (Citation2014), there are several studies to date that confirm ‘the existence of specific language features used in the dubbed target texts to convey orality’, most of them related to ‘single words, multi-word linguistic items and syntactic patterns at clause level’ (p. 10). Little attention, however, has been paid to the prosody of dubbed speech in general and to intonation in particular, which might also be an indicative of ‘the degree of standardisation and/or orality’ (Pérez-González, Citation2014, p. 9) in the dubbed text. Baños-Piñero and Chaume’s (Citation2009) work is one of the few empirical contributions that explore prefabricated orality at the phonetic-prosodic level. Their findings reveal that marked intonation units are used in dubbing as cohesive markers and that notable differences are detected between prosodic features in dubbed speech and in spontaneous speech and even between those used in dubbed speech and in fictional non-dubbed dialogue. Although the conclusions drawn from their study are highly revealing, several questions remain unanswered. If, as noted by Herbst (Citation1997), dubbed speech is easily recognisable from an acoustic point of view, can intonation be considered as one more characteristic of dubbed prefabricated orality? What tonal patterns tend to be adopted in dubbed dialogue? Do they differ from the patterns used in spontaneous and naturally-occurring speech?

This paper seeks to answer these questions by offering a descriptive-explanatory analysis of intonation in a Spanish dubbed corpus. The aim is to search for regularities in the rendition of dubbing intonation and explore their potential implications for the reception of orality by the Spanish audience. A measurable repertoire of tones (Monroy Casas, Citation2002, Citation2005; O’Connor & Arnold, Citation1973) will be examined in a number of extracts from the Spanish dubbed version of the TV series How I met your mother (Cómo conocí a vuestra madre in Spanish) via the speech analysis software SFS/WASP.

The following sections provide a general overview of how prefabricated orality and dubbing intonation have been approached in scholarly research so far, introduce the empirical study at hand and show those patterns of tonal behaviour that might characterise prefabricated orality at tone level.

2. Prefabricated orality in dubbing

Both translated and non-translated fictional dialogues can be described in terms of their written origin and their oral purpose. Whereas the scripted structure of the text seeks to be concealed or at least camouflaged, the spoken discourse strives to sound spontaneous and natural as if it had not been planned beforehand. The end product is thus a prefabricated or simulated (Valdeón, Citation2011) dialogue that aims to recreate spontaneous-like conversations while including characteristics from oral and written speech (Baños, Citation2014; Baños-Piñero & Chaume, Citation2009; Chaume, Citation2004, Citation2012) or, in other words, ‘a hybrid of written and spoken language’ (Pérez-González, Citation2014, p. 7). This prefabricated orality is evident at various linguistic levels. The work published by Baños-Piñero and Chaume (Citation2009), who exhaustively compared the Spanish dubbed version of an American TV series and a domestic sitcom in Spanish, is one of the most relevant studies on prefabricated orality conducted to date. The authors examined oral discourse from a phonetic, prosodic, morphological, syntactic, lexical, and semantic point of view and outlined the main differences and similarities between the two texts under analysis. They concluded that both dubbed and non-dubbed dialogues are far from being spontaneous and that their orality is characterised by the use of features that, despite being common in conversational speech, coexist with a very normative and artificial fictional language. Their research also shows that, unlike non-dubbed speech, Spanish dubbed dialogue is characterised by a tense phonetic articulation, a polished and correct grammatical use, syntactic fluency, and the frequent occurrence of standard vocabulary and non-specialised terminology. A number of features that evidence that the traits typifying oral and spontaneous speech are not usually present in dubbed dialogue.

The rationale behind the lack of naturalness in orality in dubbing has been explained from several angles. Romero-Fresco (Citation2012) argues that the dubbed text is not as natural as should be expected because it stems from a source text that is prefabricated in nature. The fact that the dialogues of a TV series or a film are created once the plot, the number of characters, and the duration and structure of every episode have been set has led the author to describe this type of dialogue as ‘planned to be written and to eventually be acted as if not written or planned’ (p. 187). Similarly, Zabalbeascoa (Citation2012) highlights the paradox between the translation of dialogues that are not real in the source language and the need to sound real in the target language. As it is all about creating an illusion and engaging the viewer in the fictional world, he admits that priority should not be given to the spontaneity of the dubbed text, considering that the rest of the elements of the film production do not occur spontaneously and naturally. In Baños-Piñero and Chaume’s (Citation2009) view, the difficulty does not lie so much in mirroring spoken speech but in sounding spontaneous and natural while dealing with both the signifying codes at play in dubbing and synchrony-related issues. These restrictions, however, should not always be seen as problematic. According to Baños (Citation2013), they can actually open up the door to new possibilities that might help practitioners to recreate spontaneous speech. The key is precisely to find the right balance between the oral register and the conventions followed in a given language (Chaume, Citation2004).

The description of the language used in audiovisual texts by Gregory (Citation1967) as ‘what is written to be spoken as if not written’ and what is ‘written to be read as if heard’ (pp. 191–193) can be extrapolated to dubbed texts. In fact, while translators must write the oral script performed by the original actors in a different language, dubbing actors must reproduce orally the written text elaborated by the translators. Voice talents endeavour to hide that they are reading a script just as translators strive to veil the written origin of the translated dialogue. The dubbed version can thus be regarded as the oral delivery of a written text that must be performed as if not read aloud. In this new oral version, intonation plays a pivotal role not only as a carrier of orality but also as a useful tool to recreate spontaneous and naturally-occurring conversation, even if intonation has also been planned, elaborated, and is, after all, prefabricated.

3. Dubbing intonation

In general terms, intonation can be defined as ‘the rise and fall in the pitch of the voice’ (Knowles, Citation1987, p. 204). This suprasegmental trait plays a key role in conversational exchanges. Intonation can, for instance, convey attitudinal, semantic, and pragmatic content, resolve cases of ambiguity in similar sentences, and facilitate communication between addresser and addressee. How we say something does not only accompany what we say but also complements and reinforces the meaning that the speaker wishes to convey. According to Bosseaux (Citation2018), it is ‘through particular intonations, the way words and sound are formed in the body, that we sound the way we do’ (p. 3). In fact, our utterances can be uttered with different tones and adopt different interpretations depending on our intention (Halliday, Citation1970). A question such as ‘What do you want?’ can sound more serious and abrupt when produced with a falling tone or friendly and interested with the use of a rising pattern. Contours work as a colourful palette that speakers will use to give shape and melody to their sentences and to unveil their attitudes and emotions. In dubbing, where the voice becomes the only available instrument for conveying the vocal nuances and the pragmatic load behind the original actors’ words, intonation is of paramount importance for both the production and interpretation of meaning.

The translated and adapted script in the target language is voiced by the dubbing actors under the guidance of a dubbing director. Dubbing actors must fill the empty mouths of the on-screen actors with their voices in a way that ‘they sound neither faked (overacted) nor monotonous (underacted)’ (Chaume, Citation2012, p. 19) and manage to give the illusion of reality even if viewers are well aware of the artifice of the dubbed product. Unlike on-camera and on-stage actors, who can prepare their lines and characters long before shooting a film or performing a play, voice talents must read the script, which is usually given to them immediately after they arrive at the studio for the recording session. This sense of immediacy, coupled with all the restrictions inherent to the dubbing mode itself, makes dubbing a challenging task and requires great ability and mastery on the part of the actors. While reading their lines aloud, dubbing actors need to emulate spontaneous and naturally-occurring conversations and hide the prefabricated nature of their rendition, as if ‘the story was recorded in the language you hear’ (Wright & Lallo, Citation2009, p. 219). For some authors such as Whitman-Linsen (Citation1992) and Herbst (Citation1997), however, this illusion is not always preserved, since, in their opinion, dubbed dialogues do not always manage to produce credible tonal patterns and pitch contours, thus often leading to flat, unconvincing, and unconventional intonations. Drawing once again on Baños-Piñero and Chaume’s (Citation2009) research, it seems that the delivery of phonetic and prosodic features in dubbing would be halfway between the oral and the written pole and if this level is compared to the rest of linguistic levels examined in their study, spontaneity is more apparent at the syntactic and at the lexical-semantic levels than at the morphological and at the phonetic-prosodic levels. These results provide revealing food for thought regarding dubbing intonation but still prove insufficient to determine the characteristics of prefabricated orality at tone level and their potential implications for dubbing.

Despite being a necessary tool to make communication and dubbing work (Cuevas Alonso, Citation2017), no research has yet analysed dubbing intonation empirically, what speaks volumes of the general neglect that this prosodic trait has traditionally suffered within the field of Audiovisual Translation. There is little doubt that, as has been put by Zabalbescoa (Citation1997), ‘even if we restrict translation to a purely verbal operation, nonverbal factors and their potential relevance have to be taken into account as well’ (p. 339). Indeed, the production and interpretation of the text cannot be limited to the verbal component, since nonverbal elements such as tonal patterns can supply a great deal of information that is not transmitted verbally. This study devotes dubbing intonation the attention it merits by proposing a descriptive-explanatory analysis designed to detect regularities in the use of intonation and its implications for the Spanish dubbed version.

4. The study

4.1. Corpus

The corpus comprises 360 (Castilian) Spanish dubbed utterances extracted from six episodes of the popular, Emmy-award-winning US sitcom How I met your mother (Bays & Thomas, Citation2005–Citation2014). This comedy, on TV for nine seasons, tells the story of Ted and all the events that led him to meet the mother of his two children. For the descriptive analysis of intonation, episode 17 of seasons 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, and 9 was randomly selected. The first 20 statements, 20 questions, 10 exclamations, and 10 commands of every episode were singled out for the research, thus featuring a total of 60 utterances under examination per episode. The difference in the number of utterance types arises from the higher occurrence of statements and questions in the audiovisual product as compared to the frequency of exclamations and commands. Therefore, the number of utterance types selected for the analysis runs parallel to the total number of utterance types found in a whole episode. Given the time-consuming and arduous task of cutting the audio extracts, inserting them into the software, and analysing each one of them separately, we tried to gather a representative sampling according to the amount of time needed to analyse the entire corpus. As priority was given to complete intonation units with semantically lexical content, one-word phrases, dialogue fillers, and routine formulae were intentionally discarded from the analysis.

4.2. Methods

The methodology adopted in this study is based on the descriptive-explanatory approach envisaged by Saldanha and O’Brien (Citation2013) for ‘the analysis of texts in their context of production and reception’ (p. 50). As intonation is context-dependent (Wray & Fitzpatrick, Citation2010), tones need to be interpreted and examined in relation to the particular context they are uttered in (Hirst & Di Cristo, Citation1998). By means of this approach the researcher can thus obtain a more objective view of translational behaviour and describe/explain the regularities found in the utterances under scrutiny by taking into account both their context of production and their context of reception.

For the analysis, a repertoire of tones was necessary. The classification of tonal patterns tends to vary according to the authors and their theoretical backgrounds. The most common factors determining the choice of an intonational taxonomy are as follows: the trajectory of the nucleus, the beginning point of the pitch direction and, if applicable, the change of trajectory after the tonic segment (Cruttenden, Citation1997). Drawing on O’Connor and Arnold (Citation1973) and Monroy Casas (Citation2002), a lexicon of nine tones including three types of tonal movements was selected for the analysis: 3 falling tones (low fall, high fall, and rise-fall), 3 rising tones (low rise, high rise, and fall-rise), and 3 level tones (low level, mid level, and high level). This repertoire constitutes an accurate and representative intonational modelling for the examination of the dubbed corpus.

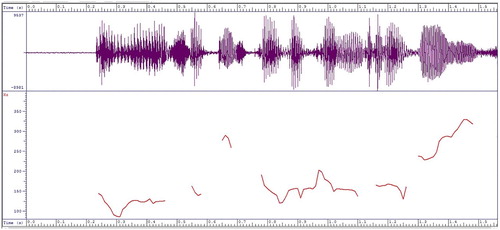

Since the analysis combined auditory and visual inspections of the patterns under study to ensure the degree of accuracy, a speech analysis programme (SFS/WASP v. 1.41) developed by Mark Huckvale, University College London, was used for the analysis of intonation. This application allows the introduction of audio files and provides the pitch contour and waveform of single utterances. For the sake of illustration, shows a typical display obtained from the software. The utterance’s wideband spectrogram is displayed at the top and its pitch contour is outlined at the bottom.

4.3. Procedure

The first stage of the analysis consisted of the transcription of the dubbed script and the classification of the utterances into statements, questions, exclamations, and commands. As mentioned above, one-word phrases, dialogue fillers as well as routine formulae, which were not applicable for the analysis, were discarded during this phase. Narrated fragments were also dismissed to avoid a tonal delivery motivated by an intended story-telling style that differs from colloquial intonation. Then, the first 20 statements, 20 questions, 10 exclamations, and 10 commands featured in every episode under study were selected and cut with an online audio cutter. The second step was to introduce the aural fragments into the software to obtain the pitch contour of the dubbed utterances. In total, 360 utterances (120 statements, 120 questions, 60 exclamations, and 60 commands) were examined. The next step involved the auditory and visual inspection of the contours produced by the programme by the researcher of this study in order to assess and determine the tonal movements per utterance type. The corpus was then divided into falling, rising, and level tones and analysed both quantitatively and qualitatively in order to identify and describe the regularities followed in the use of intonation in the Spanish dubbed corpus. Finally, several conclusions were drawn about the potential impact that the findings obtained could exert on the prefabricated orality and reception of the dubbed version in the target language.

5. Main findings

5.1. Falling tones

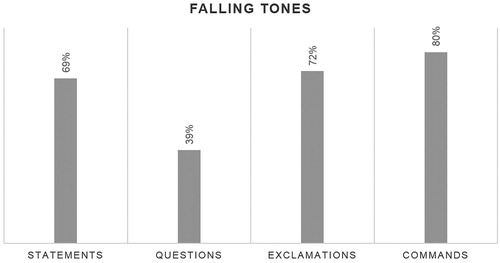

The quantitative findings obtained from the analysis reveal that the fall is the most recurrent tone in statements (69%), exclamations (72%), and commands (80%), thus corroborating what authors such as Navarro Tomás (Citation1944), García-Lecumberri (Citation1995) or Monroy Casas (Citation2002) had already postulated regarding (Castilian) Spanish intonation. In spoken discourse, the use of a falling tone tends to imply that the utterance is definite and complete. In written speech, definiteness and completeness are generally represented with a full stop. As far as questions are concerned, the descending movement is generally associated with wh-questions, which take a fall by default unless the speaker wishes to convey a particular meaning. In the corpus under study, most interrogatives produced with a falling tone (39%) were wh-questions. Data on the occurrence of falling tones per utterance type are included in below.

Paying attention now to the three types of falling tones under examination, results show a different frequency of occurrence of the high fall, the low fall, and the rise-fall in the utterances analysed. In statements, questions, and commands, low falling tones substantially outnumber high falling tones, whereas the rise-fall is very rare (7% in declarative and imperative sentences) or completely absent (0% in questions). Regarding exclamations, the high fall and the low fall are used very similarly in the Spanish corpus and yet the high variant (32%) is slightly more recurrent than the low variant (30%). The rise-fall also occurs more frequently in exclamative sentences (10%) than in the rest of utterance types. A general overview is provided in .

Table 1. Occurrence of the high fall, the low fall, and the rise-fall per utterance type.

The most salient feature of falling patterns shown in is the frequent repetition of low falling tones in the Spanish dubbed sitcom. Given that the high and low pitch-ranges on the nuclear tone can carry different types of implications, such trend becomes especially relevant from the point of view of dubbing. According to Wells (Citation2006), ‘the higher the starting point of a simple fall, the greater the degree of emotional involvement’, whilst, on the contrary, ‘the lower the starting point, the less the emotional involvement’ (p. 218). Along similar lines, Cruttenden (Citation1997) argues that ‘the low fall is generally more uninterested, unexcited and dispassionate whereas the high-fall is more interested, more excited, more involved’ (p. 19). Cruttenden’s opinion is also partaken by Tench (Citation2011), who considers that the high fall tends to be livelier and more emphatic than than the low fall. By this, it is suggested that high and low falling patterns are bound to be perceived differently in oral language. If the frequent recourse to low falls can bring about a more unemphatic and dispassionate delivery devoid of the involvement and liveliness generally conveyed by a high key (Monroy Casas, Citation2002), dubbed characters might sound more detached and less involved from an emotional and pragmatic viewpoint. Additionally, the dominance of low patterns in an episode could clearly produce a monotonous delivery perceived by the audience’s ear as somewhat deflated and even artificial.

Judging by the results obtained in the analysis, Spanish dubbing actors very often resort to low falling contours to deliver their lines, except for the rendition of exclamative sentences, where the number of high falls slightly exceeds the number of low falls. The rationale behind this can be found in the expressive and dramatic load characterising this utterance type (Sánchez-Mompeán, Citation2019). The need to offer a more intense and emotional performance when dubbing the exclamations used by the original actors might explain why voice talents tend to produce exclamations with high falling patterns, a very common tone to convey and even reinforce the expressiveness attached to this sentence type (Monroy Casas, Citation2002; Navarro Tomás, Citation1944).

The use of the rise-fall in exclamations is also more recurrent than in the rest of the utterance types of the corpus. Such finding is not surprising if seen as a reflection of the intensity and emphasis that can be conveyed with this tone by the speaker (Monroy Casas, Citation2005; Navarro Tomás, Citation1944) and the possibility of sounding ‘greatly impressed by something not entirely expected’ (O’Connor & Arnold, Citation1973, p. 82), an attitude that could be associated with the use of exclamations in speech. In contrast, rise falling patterns are completely absent in the questions under analysis, an expected finding given the scarcity of the rise-fall to ask questions in standard Spanish. This tone, according to Monroy Casas (Citation2002), ‘only occurs with certain types of statements and exclamations’ (p. 15) and rarely with imperatives. We have found, however, that the dubbing actors of the sitcom have sometimes opted for the rise-fall when other tone could have sounded more natural in Spanish in that particular context. Some of the cases identified in the dialogue could be explained by Monroy Casas (Citation2002), who argues that this tone is commonplace amongst certain peninsular local accents. Unfortunately, given the small sample size available (7% in statements, 10% in exclamations and 7% in commands), more research would be necessary to confirm or refute such hypothesis in the dubbed corpus under study.

5.2. Rising tones

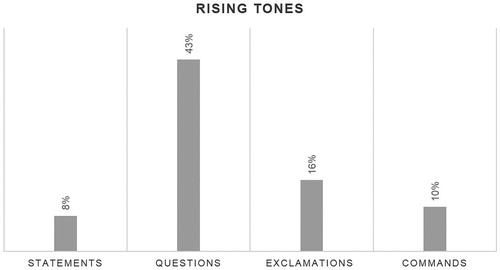

Rising intonation is the default tone for general questions such as yes/no questions or polar questions, except for wh-questions, which usually take a fall. Other types of interrogatives that merit further consideration here are tag questions due to the intonational differences found between English and Spanish. In English these questions can be uttered with a rising or a falling tone depending on the speaker’s intention. With a rise the addresser asks for information or seeks argument, whereas the fall puts in a request for confirmation or appeals for agreement. Such distinction does not tend to apply in Spanish. In this language a rise is generally adopted regardless of the type of request put in by the speaker (Valenzuela Farías, Citation2013), so the ascending movement is always prioritised. The rise, however, is not only associated with the questioning form. Non-finality and incompleteness can be conveyed with an ascending movement in statements, exclamations, and commands. In these types of utterances, the rise can be intentionally employed by the addresser in order to fulfil an illocutionary or attitudinal function that is superimposed on the denotative content of the word or sentence (Collins & Mees, Citation2003). This can explain why their occurrence is not very common in the corpus: 8% in statements, 16% in exclamations, and 10% in commands, whereas questions feature 43% of rising tones, as shown in .

Having a look at the results obtained per tone type (see below), the number of high rising patterns (34%) in questions clearly predominates over the low rise (9%) and the fall-rise (0%). In statements the low rise (5%) is slightly more recurrent than the high rise (3%), whereas the percentage of high rising patterns in exclamations (8%) and commands (5%) is exactly the same as the percentage of low rising patterns. It is also worth mentioning the total absence of the fall-rise in all the utterances analysed in the corpus. This finding goes in line with Monroy Casas’s (Citation2005) statement that ‘the fall rise constitutes part of the Spanish tonal system, but it has a restricted use due partly to a narrower range of uses than in English’ (p. 12).

Table 2. Occurrence of the high rise, the low rise, and the fall-rise per utterance type.

The use of the high rise in polar and echo questions is very recurrent in standard Spanish (Monroy Casas, Citation2005; Navarro Tomás, Citation1944). The quantitative data obtained in the dubbed corpus corroborate the tendency amongst voice talents to resort to high rising patterns when delivering these types of questions, mainly when the same pattern has been used in the original version. The similarity between English and Spanish in the conveyance of the high rise might be posited as a potential explanation for the recourse to this tone in the dubbed dialogue. The low rise is also very recurrent in Spanish interrogative sentences (Monroy Casas, Citation2005; Navarro Tomás, Citation1944). Yet, the utterances produced with this tone are scarce in the dubbed corpus. According to Cruttenden (Citation2008), ‘the more usual and more polite way of asking yes/no questions [in English] is with the low rise’ (p. 285), but he admits that the high rising has become widespread amongst American speakers. The scarcity of the low rise in Spanish dubbing could be explained by the potential influence that the original actors’ intonation could exert on the dubbing actors’ delivery. In fact, when they listen to the English utterance just before starting to dub, they might (un)consciously adopt the tone used by the original speaker, which might not necessarily be the most natural option in Spanish in that particular context.

As far as statements and exclamations are concerned, the ascending movement on the nuclear tone is quite rare in everyday speech and, when present, it usually performs a specific attitudinal or pragmatic function (Monroy Casas, Citation2012). It is worth pointing out that some of the statements and exclamations uttered with a low rise in Spanish have also been found to be imitating the tone used by the original actor in English, when the voice talent could have opted for a more natural or spontaneous pattern in Spanish to convey the meaning and attitude intended by the character. A different finding emerged from the analysis of dubbed commands, which sometimes adopt an ascending movement when the English utterance adopts a descending movement. This change has clear implications for the audience’s perception, given that the firm and authoritative tone implied by the original command is softened to a request in the dubbed version with the use of a rising tone.

5.3. Level tones

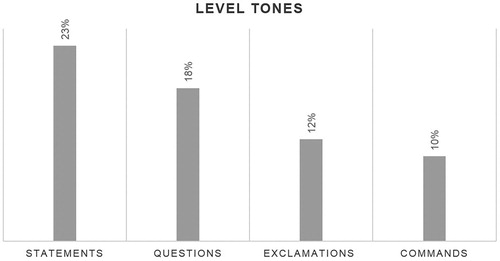

The quantitative analysis reveals that the level is a popular tone to utter statements, exclamations, and commands in the dubbed corpus and yet this tone type does not occur as frequently as falling tones. Although it is characterised by an absence of movement on the nuclear tone, it does not necessarily sound monotonous, for other parts of the utterance (i.e., the head and pre-head) contribute to its melodic movement. The level tone has traditionally been associated with incomplete information and continuation in non-final position (O’Connor & Arnold, Citation1973; Tench, Citation2011). In compound declarative sentences, for instance, the level has proved very frequent to convey non-finality as well as enumerations and listings in Spanish. Despite being a recurrent tone in non-final position, the level trajectory of the pitch can also be used in final position and, according to linguists such as Monroy Casas (Citation2002), it actually abounds in Spanish naturally-occurring speech, an opinion that is not embraced by all scholars in the field.

In the dubbed corpus, 23% of statements have been uttered with a level, thus becoming the second most common tone just after the fall. When it comes to questions, the occurrence of this tone is fairly recurrent in both wh-questions and polar questions, featuring 18% in the dubbed sitcom. In exclamations and commands, the level tone is not as frequent as the falling movement in the Spanish corpus: 12% in exclamative sentences and 10% in commands. Data on the occurrence of the level tone per utterance type have been included in .

As shown in below, high, mid, and low level tones are present in the four utterance types under study but feature a differing rate of occurrence. In dubbed statements, the low level tone (15%) predominates over the mid (4%) and high (4%) level tones. Similarly, the low level (8%) is slightly more frequent than the high level (7.5%) in dubbed questions, while the frequency of occurrence of the mid level is pretty low (2.5%). Exclamations produced with a mid level are more recurrent (7%) than those delivered at a high (3%) and low (2%) level. Finally, the quantitative analysis indicates that the number of level tones in commands is quite proportionate: 5% of commands are produced with a high key, 3% with a mid key, and 2% with a low key.

Table 3. Occurrence of the high level, the mid level, and the low level per utterance type.

Similar to dubbed falling patterns, the dominance of the low level in statements and questions can be posited as one of the main trends identified in the dubbed corpus. According to Monroy Casas (Citation2005), whereas the mid level tone is the most common key to produce sentences with a level tone in English, all three keys, namely high, mid, and low, occur frequently in Spanish. Level tones do not sound as authoritative and conclusive as falling contours and can imply ‘absence of emotional involvement’ (p. 17), but they can be used in final position to indicate completeness. This is the case of some of the declarative sentences under analysis. Although the dubbing actor can resort to the low level tone to convey finality, an abundance of low level patterns can be perceived as more detached and dispassionate than the mid or high level tone, thus producing a more deflated dialogue in Spanish. In exclamations, findings show that the mid level is more common than the high and low keys, what can again be explained by the expressive and dramatic load typifying this utterance type. In most occasions, however, the high pattern could have contributed to reinforcing the affective or emotional involvement of the original character.

The quantitative analysis also indicates that questions are mainly produced with either a low level pattern or a high level pattern. Both tones are often used in Spanish when uttering different types of interrogative sentences. Finally, commands with a high key predominate slightly over commands produced with a mid or low level, but the three variations have proved to be present in the dubbed corpus, even though they represent a small quantity as compared to the number of commands uttered with a falling tone. In this particular case, the original dialogue does not seem to have motivated the intonation adopted by the dubbing actors in their delivery of questions and commands with a high, mid or level tone, maybe because this pattern is unusual in English and is not always included by authors in the intonational lexicon of this language (Halliday, Citation1970; Monroy Casas, Citation2005; O’Connor & Arnold, Citation1973).

6. Conclusions and final remarks

The focus of analysis has been placed on dubbing intonation, more specifically, on the tonal patterns that are regularly found in dubbed speech and are bound to characterise prefabricated orality at tone level. For this purpose, the software SFS/WASP has been used as an effective tool to examine nine tones in 360 utterances extracted from the Spanish dubbed version of the sitcom How I met your mother. The results show a general tendency towards low patterns in most of the utterances under analysis. As explained by linguists such as Cruttenden (Citation1997), Wells (Citation2006), and Tench (Citation2011), the low pattern is usually characterised for being less emphatic, involved, and lively than the high pattern. As a result, the repetition of low patterns in the dubbed dialogue could produce a less dynamic and more monotonous delivery on the part of the dubbing actors that could be perceived by the target audience as somewhat deflated and even artificial. This is not the case, however, of most exclamations produced with a fall or a level tone and questions produced with a high rise. The dramatic and expressive load attached to these utterance types and the similarity of English and Spanish patterns when delivering exclamatives and interrogatives with a high key could account for their bias in favour of a more spontaneous rendition in the dubbed dialogue.

Data also reveal that one feature of dubbed speech is the co-existence of tonal patterns that are recurrent in spontaneous discourse with other patterns that do not abound in spontaneous intonation. This unusual combination could be explained by the potential influence that the original actors’ intonation exerts on the voice talents’ delivery, thus (un)consciously leading dubbing actors to imitate some tonal patterns that might not be the most natural-sounding option in Spanish in that particular context. One more finding that could have an impact on the audience’s perception is the delivery of several dubbed commands. Although more research on this issue would be necessary, the available data seem to reveal that they do not always reflect the original speaker’s intention, given that they sometimes sound as a request in Spanish when the English character is putting in a firm and authoritative order. Once again, the ensuing dialogue could be perceived by the public as less emphatic and involved than its non-dubbed counterpart.

The main trends identified in the analysis speak volumes of the prefabricated orality of dubbed dialogue at tone level. In the same way that the language of dubbing has been described as a type of dialogue that departs from spontaneous speech but it is not as spontaneous as one would expect (Baños, Citation2014; Baños-Piñero & Chaume, Citation2009; Brutti & Zanotti, Citation2012; Chaume, Citation2004; Romero-Fresco, Citation2009), dubbing intonation seems to be characterised by a combination of spontaneous and non-spontaneous orality and the use of several patterns that, repeated during an episode, could reinforce the artificial and contrived nature of dubbed dialogue. Interestingly, the melody resulting from the repetition of these patterns is characteristic of dubbed dialogue and even recognisable as such by the general public. Although, as mentioned above, some of these trends can exert a negative impact on the audience’s perception, viewers do not necessarily have to be disrupted by dubbing intonation. In fact, they can disregard its prefabricated nature by suspending disbelief, in this case, by suspending prosodic disbelief. Romero-Fresco (Citation2009) defines this notion as ‘the process that allows the dubbing audience to turn a deaf ear to the possible unnaturalness of the dubbed script while enjoying the cinematic experience’ (pp. 68–69). He explains that viewers do not compare what they are hearing to what they would hear in a similar real-life conversation but to ‘their memory of that sound’ (p. 68), influenced by what they are used to hearing in other dubbed products. Taking the author’s description as a starting point, the suspension of prosodic disbelief would then involve accepting that how on-screen characters say what they say may not necessarily sound as they would sound in a similar real-life situation, but as on-screen characters usually sound in dubbed products.

There is little doubt that the study of nonverbal features in general and of intonation in particular is paramount in dubbing, where the actors’ delivery does not only have to be translated and adapted into a new language but also interpreted and delivered by dubbing actors. The dialogue is expected to sound credible and realistic not only from a linguistic point of view but also from a prosodic and acting perspective (Chaume, Citation2007, Citation2012). Intonation contributes to the recreation of a credible-sounding dialogue and voice talents should master the whole repertoire of tones in their own language in order to offer a wide range of dramatic nuances with their voice. In Culpeper’s (Citation2001) words, ‘the text is assumed to provide the verbal component and the actor the nonverbal component’ (p. 40), which points to the essential need to work in tandem during the process and foster collaboration amongst all the professionals involved in order to convey what characters say and how they say it.

The present research could be expanded in many different ways, being reception studies one of them. This avenue has certainly ‘become pivotal in recent academic exchanges, with the viewer becoming the focal point of the investigation’ (Baños & Díaz-Cintas, Citation2018, p. 322) and is definitely opening up a promising landscape in dubbing research (Sánchez-Mompeán, Citationin press). The limitations found in our study also allow for a broader analytical model, including the examination of different prosodic features such as rhythm or speed of delivery, which could cast light on the study of prefabricated orality in dubbed dialogue and on their potential effects on the characters’ perception. The important role of intonation could also be explored in other audiovisual translation modes and even in different genres. These are just some developments that might once and for all help to put a spotlight on an almost unexploited – and yet highly fertile – field of research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Sofia Sánchez-Mompeán is an assistant professor at the Department of Translation and Interpreting at the University of Murcia and a member of the research groups GALMA (Galician Observatory for Media Accessibility) and TECTRAD (Technology and Translation). She holds a PhD and MA in Audiovisual Translation (University of Murcia and University of Roehampton) and a BA in Translation and Interpreting (University of Murcia, Spain). She has been awarded several recognitions for her research on the rendition of English intonation in Spanish dubbing and has enjoyed several academic stays in a number of universities worldwide. She has also worked as a dubbing actress, lending her voice to adverts and animated short films, and as a freelance translator, subtitler and proofreader. Her main research interests include the dubbing-prosody interface, the translation of non-verbal information in dubbed and subtitled texts and the integration of dubbing into the filmmaking process.

ORCID

Sofía Sánchez-Mompeán http://orcid.org/0000-0002-2676-3888

References

- Baños, R. (2013). ‘That is so cool’: Investigating the translation of adverbial intensifiers in English-Spanish dubbing through a parallel corpus of sitcoms. Perspectives, 21(4), 526–542. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2013.831924

- Baños, R. (2014). Orality markers in Spanish native and dubbed sitcoms: Pretended spontaneity and prefabricated orality. Meta: Journal des Traducteurs, 59(2), 406–435. doi: 10.7202/1027482ar

- Baños, R., & Díaz-Cintas, J. (2018). Language and translation in film: Dubbing and subtitling. In K. Malmkjaer (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of translation studies and linguistics (pp. 313–326). London/New York: Routledge.

- Baños-Piñero, R., & Chaume, F. (2009). Prefabricated orality: A challenge in audiovisual translation [Special issue]. inTRAlinea. Retrieved from http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/Prefabricated_Orality

- Bosseaux, C. (2018). Voice in French dubbing: The case of Julianne Moore. Perspectives. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2018.1452275

- Brutti, S., & Zanotti, S. (2012). Orality markers in amateur and professional subtitling. In C. Buffagni, & B. Garzelli (Eds.), Film translation from East to West. Dubbing, subtitling and didactic practice (pp. 167–192). Bern: Peter Lang.

- Bucaria, C. (2008). Acceptance of the norm or suspension of disbelief? The case of formulaic language in dubbese. In D. Chiaro, C. Heiss, & C. Bucaria (Eds.), Between text and image. Updating research in screen translation (pp. 149–164). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Chaume, F. (2004). Cine y traducción [Cinema and translation]. Madrid: Cátedra.

- Chaume, F. (2007). Quality standards in dubbing: A proposal. TradTerm, 13, 71–89. doi: 10.11606/issn.2317-9511.tradterm.2007.47466

- Chaume, F. (2012). Audiovisual translation: Dubbing. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing.

- Collins, B., & Mees, I. M. (2003). Practical phonetics and phonology. London/New York: Routledge.

- Cruttenden, A. (1997). Intonation (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cruttenden, A. (2008). Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (7th ed.). London: Hodder Education.

- Cuevas Alonso, M. (2017). Multimodalidad, comunicación y doblaje. La entonación [Multimodality, communication and dubbing. Intonation]. In X. Montero Domínguez (Ed.), El Doblaje. Nuevas vías de investigación (pp. 49–63). Granada: Editorial Comares.

- Culpeper, J. (2001). Language and characterisation: People in plays and other texts. Essex: Pearson Education Limited.

- García-Lecumberri, M. L. (1995). Intonational signalling of information structure in English and Spanish. Bilbao: UPV/EHV.

- Gregory, M. (1967). Aspects of varieties differentiation. Journal of Linguistics, 3(2), 177–198. doi: 10.1017/S0022226700016601

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1970). A course in spoken English: Intonation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Herbst, T. (1997). Dubbing and the dubbed text – style and cohesion: Textual characteristics of a special form of translation. In A. Trosborg (Ed.), Text tipology and translation (pp. 291–308). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Hirst, D., & Di Cristo, A. (1998). A survey of intonation systems. In D. Hirst, & A. Di Cristo (Eds.), Intonation systems: A survey of twenty languages (pp. 1–44). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Knowles, G. (1987). Patterns of spoken English: An introduction to English phonetics. London: Longman.

- Monroy Casas, R. (2002). El sistema entonativo del español murciano coloquial. Aspectos comunicativos y actitudinales [The intonation system of colloquial Murcian Spanish. Attitudinal and communicative aspects]. Estudios Filológicos, 37, 77–101.

- Monroy Casas, R. (2005). Spanish and English intonation patterns. A perceptual approach to attitudinal meaning. Pragmatics & Beyond New Series, 140, 307–324. doi: 10.1075/pbns.140.21mon

- Monroy Casas, R. (2012). La pronunciación del inglés británico simplificada [British English pronunciation made simple]. Murcia: Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Murcia.

- Navarro Tomás, T. (1944). Manual de entonación española [A manual on Spanish intonation]. New York: Hispanic Institute in the United States.

- O’Connor, J. D., & Arnold, G. F. (1973). Intonation of colloquial English (2nd ed.). London: Longman.

- Pavesi, M. (1996). L’allocuzione del doppiaggio dall’inglese all’italiano [Dubbed speech from English into Italian]. In C. Heiss, & R. M. Bollettieri (Eds.), Traduzione multimediale per il cinema, la televisione e la scena (pp. 117–130). Bologna: CLUEB.

- Pérez-González, L. (2014). Audiovisual translation: Theories, methods and issues. London/New York: Routledge.

- Romero-Fresco, P. (2009). Naturalness in the Spanish dubbing language: A case of not-so-close Friends. Meta: Journal des traducteurs, 54(1), 49–72. doi: 10.7202/029793ar

- Romero-Fresco, P. (2012). Dubbing dialogues … naturally: A pragmatic approach to the translation of transition markers in dubbing. MonTI. Monografías de Traducción e Interpretación, 4, 181–205. doi: 10.6035/MonTI.2012.4.8

- Saldanha, G., & O’Brien, S. (2013). Research methodologies in translation studies. London/New York: Routledge.

- Sánchez-Mompeán, S. (2019). Dubbing attitudes through tonal patterns: When tones speak louder than words. VIAL, 16, 135–155.

- Sánchez-Mompeán, S. (in press). Tendencias actuales de investigación en doblaje y su influencia en la competencia traductora [Research trends in dubbing and their impact on translation competence]. Article accepted for publication.

- Tench, P. (2011). Transcribing the sounds of English: A phonetics workbook for words and discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Valdeón, R. A. (2011). Dysfluencies in simulated English dialogue and their neutralization in dubbed Spanish. Perspectives, 19(3), 221–232. doi: 10.1080/0907676X.2011.573079

- Valenzuela Farías, G. (2013). A comparative analysis of intonation between Spanish and English speakers in tag questions, wh-questions, inverted questions and repetition questions. Revista Brasileira de Linguística Aplicada, 13, 1061–1083. doi: 10.1590/S1984-63982013005000021

- Wells, J. (2006). English intonation: An introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Whitman-Linsen, C. (1992). Through the dubbing glass. The synchronization of American Motion Pictures into German, French and Spanish. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Wray, A., & Fitzpatrick, T. (2010). Pushing learners to the extreme: The artificial use of prefabricated material in conversation. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 4(1), 37–51. doi: 10.1080/17501220802596413

- Wright, J. A., & Lallo, M. J. (2009). Voice-over for animation. London: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers.

- Zabalbescoa, P. (1997). Dubbing and the non-verbal dimension of translation. In F. Poyatos (Ed.), Nonverbal communication and translation (pp. 327–342). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

- Zabalbeascoa, P. (2012). Translating dialogues in audiovisual fiction. In J. Brumme, & A. Espunya (Eds.), The translation of fictive dialogue (pp. 63–78). New York: Rodopi.

- Filmography

- Bays, C., & Thomas, C. (Producers). (2005–2014). How I met your mother [Television series]. USA: 20th Television.