ABSTRACT

This article presents a rare cross-national comparative study of translators’ status perceptions, examined by means of two sets of survey data collected in Finland in 2014 (n = 397) and in Sweden in 2016 (n = 359). This comparison is of particular interest since the two countries share many characteristics, albeit with notable differences as to the role of translation in society and the history of translator education and associations. Following Dam and Zethsen (e.g., 2008), we compare the respondents’ views of five variables: status, income, expertise/education, visibility and power/influence, which are ranked on a five-point Likert scale. Mann–Whitney U tests indicated statistically significant differences between the two datasets in most items. While there were no clear tendencies by variable, the items where the Finnish respondents’ rankings were higher can be linked to the role of translation in society and to more established translator education in Finland. In contrast, the Swedish respondents’ higher rankings may be explained by a large proportion of respondents with decades of working experience. Overall, the results highlight the importance of collecting comparable data and analysing even apparently similar perceptions for differences.

1. Introduction

In this article, we present what is one of the first truly cross-national comparative studies on translator status (cf. Ruokonen, Citation2013), analysing translators’ status perceptions by means of data collected in Finland in 2014 (n = 397) and in Sweden in 2016 (n = 359). Previous status studies include international surveys (Gentile, Citation2013; Katan, Citation2009) and country-specific comparisons among translators in different positions of employment or with different specialisations (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2011, Citation2012; Ruokonen, Citation2018; Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018; Svahn, Citation2020). However, to our knowledge, there are no studies comparing translators’ status perceptions in different countries apart from Liu (Citation2021). Finland and Sweden provide a particularly interesting setting for such a study: although both are Nordic societies where translation plays a major role, that role has been more pronounced in the development of the Finnish language and literature, and Finland also has a longer history of translator education and translators’ associations. It is interesting to see whether and how these differences are reflected in the data.

To begin with a brief overview of previous research, it should first be noted that status is a rather slippery concept. Ruokonen and Mäkisalo (Citation2018, pp. 2–3) identify the following five meanings of status:

the status of a fully-fledged profession (as opposed to an occupation);

the socio-economic status of an occupation as a product of income and educational level;

status as occupational prestige: perceptions of value and appreciation attached to an occupation;

status as market value produced by signals of expertise and trustworthiness; and

the status that individual agents negotiate themselves in a particular context.

Previous research indicates that translators in various countries and contexts rank their overall status as mid-level or lower (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2011, Citation2012; Katan, Citation2009, p. 126; Liu, Citation2021, p. 8; Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, p. 8; Svahn, Citation2020, p. 71). More specifically, translators have characterised their status as similar to that of teachers and secretaries (Katan, Citation2009, p. 127) and as lower than that of interpreters (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2013, pp. 241–242; Gentile, Citation2013, pp. 76–77; Katan, Citation2009, pp. 126–127). Translators also feel that their occupation is not very visible, and this sense of invisibility correlates with low status perceptions (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2011, pp. 991–992; Citation2012, p. 226; cf. Sook Kang & Shunmugam, Citation2014, pp. 200–201).

In contrast to this mid-level overall status, translators can feel highly appreciated at their workplace or by their commissioners (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2009, p. 29; Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, p. 9; Svahn, Citation2020, p. 68; Virtanen, Citation2020, pp. 100–102). Another contrast emerges in terms of expertise and skills: while translators believe their expertise is not sufficiently recognised by people outside the field, they themselves consider translation to require a high degree of specialised skills, knowledge and expertise (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2011, p. 988; Katan, Citation2009, pp. 123–124; Liu, Citation2021, p. 8; Ruokonen, Citation2019, p. 115; Setton & Guo Liangliang, Citation2011 [Citation2009], p. 106; Sook Kang & Shunmugam, Citation2014, pp. 200–201; Svahn, Citation2020, pp. 61–63).

Differences in status perceptions highlighted by previous research mainly concern translators working in different positions and conditions. Firstly, status perceptions among Danish business translators varied to some extent between in-house translators and freelancers, and among in-house translators at translation agencies, other companies and within the EU (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2011, pp. 984–986; Citation2012, p. 220). Interestingly, although literary translators are often thought to enjoy a higher status than business and audio-visual translators, such differences did not emerge among Finnish translators (Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, p. 10). Even an authorised translator’s qualification produced no statistically significant differences (Ruokonen, Citation2018). In contrast, Svahn (Citation2020, p. 71) found that Swedish literary translators had higher status perceptions than non-literary translators, whereas business translators had lower status perceptions than non-business translators.

Secondly, translators’ working conditions may be connected to their status perceptions. Among Finnish translators, those respondents who frequently experienced negative stress and had to produce low-quality translations were more likely to feel unappreciated at work (Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, pp. 12–13). Similarly, those respondents who frequently considered leaving the translation industry ranked both their appreciation at work and translators’ overall status as lower than those with no turnover intentions (Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, pp. 12–13).

Differences in status perceptions in different countries have thus far only been explored by Christy Fung-ming Liu (Citation2021) in a survey with 425 translator respondents from ten Asian countries. The survey focused on professionalism, but included status as one parameter. Overall, the respondents characterised their status as mid-level, but there were statistically significant differences between the countries: the Indian, Philippine and Malaysian respondents reported the highest status perceptions, while the lowest rankings came from Singapore, South Korea and Japan (Liu, Citation2021, pp. 8, 11). However, the low number of respondents – particularly from India (n = 5), Malaysia (n = 6) and the Philippines (n = 7) – limits the overall insight that can be gained from the study.

In the present article, we complement previous research by comparing Finnish and Swedish translators’ status perceptions on the basis of data collected from surveys replicating Dam and Zethsen’s questionnaires. Our datasets, collected in 2014 and 2016, consist of 397 and 359 respondents, including audio-visual, business and literary translators. We consider the respondents’ perceptions of their status and the related variables of income, expertise/education, visibility and power/influence. Our aim is to discover what kinds of statistically significant differences emerge on the basis of the respondents’ national backgrounds and in what respects these differences can be linked to the role of translation and translational institutions in the two countries.

In what follows, Section 2 describes the role of translation, translator education and translators’ associations in Finland and Sweden. Section 3 then provides background information on the two datasets and the analysis method. In Section 4, we present the statistical differences between the two datasets, which is followed by a discussion (Section 5) and concluding remarks.

2. The Finnish and Swedish contexts

Finland and Sweden are two neighbouring countries which are similar in several respects. Both societies are examples of the ‘Nordic model’ with extensive, publicly provided social services and labour market regulation combined with a market economy (Andersen et al., Citation2007). Both are multilingual societies where translation plays a major role in administration and culture, as illustrated in what follows.

The countries also have close ties. Areas of Finland were part of Sweden from the Middle Ages until 1809. As a result, legal, religious and literary texts were frequently translated from or through Swedish (Lilius, Citation2003). Swedish was also widely used in Finnish administration until a decree passed in 1863 strengthened the status of Finnish (Lehikoinen & Kiuru, Citation1991). Even today, Swedish remains one of the two official languages in Finland, in addition to Finnish, and Finnish enjoys the status of a national minority language in Sweden.

Despite this shared history, Finnish and Swedish are very different languages. Like English, Swedish is an analytic language that relies on word order and prepositions to express grammatical relationships, while Finnish is an agglutinative language that makes extensive use of suffixes. As English and Swedish are translators’ most common working languages in Finland after Finnish (Sevänen, Citation2007; Wivolin, Citation2012), Finnish translators need to pay close attention to producing idiomatic Finnish and avoiding source-language interference.

In Finland, translation has a more central role than in Sweden, both historically and today. In the European context, Finnish is a fairly young written language: although the first Finnish books were published in the sixteenth century, it was only in the 1850s that the norms of written Finnish were established. Moreover, Finnish language and literature were largely developed through translations; Munday (Citation2016, p. 172) mentions Finland as an example of a ‘young’ literary polysystem where translated literature has occupied a central position. Even today, approximately half of the published literature is translated, mostly from English (Sevänen, Citation2007). English is also the most widely used foreign language in daily life (Leppänen et al., Citation2011). In administrative contexts, translation between Finnish and Swedish has a major role due to the status of Swedish as an official language. In addition, the speakers of the Sami languages, the Romani language and Finnish and Swedish sign languages enjoy certain legally decreed rights. Common foreign languages spoken in Finland include Russian, Estonian, Somali and Arabic (Institute for the Languages of Finland, Citation2013).

Similarly to Finland, translation has occupied a prominent position in Sweden’s literary market with translations accounting for 16–41% of the total number of published literature (Lindqvist, Citation2002, p. 36, Citation2016, p. 178; Axelsson, Citation2016, p. 21). However, in contrast to Finland, Sweden has been conceived as the centre of a literary Scandinavian sub-field in a polysystemic sense (Lindqvist, Citation2016). Swedish also has a longer history as a written language, with the oldest written sources dating back to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; the translation of the Gustav Vasa Bible in 1526 marks the beginning of Modern Swedish. Nowadays, Swedish is the majority language in Sweden (Institute for Language and Folklore, Citation2020) counting 10 million speakers, and, as of 2009, the Swedish Language Act governs its use in society. English is also widely used, and the three other most common foreign languages are Arabic, Finnish, and Bosnian-Croatian-Serbian; Finnish was the second most common foreign language for 800 years until 2015 (Parkvall, Citation2016, Citation2018). The five national minority languages are Finnish, Yiddish, Meänkieli, Romani Chib and Sami, and Swedish sign language also enjoys a similar status.

In terms of translator education, Finland has a longer history. Translator education for business translators was institutionalised in the 1960s with the establishment of ‘language institutes’ (in Finnish, kieli-instituutti) that offered a three-year vocational training programme. In 1981, translator training was transferred to universities and expanded into a five-year programme consisting of BA and MA degrees. Within the past decade, most translation programmes have been condensed into MA degrees. Currently, translator education is offered at the universities of Eastern Finland, Helsinki, Tampere and Turku.

In contrast, in Sweden, while universities’ foreign language departments began offering some translation teaching in the 1960s, these were short, professionally-oriented courses, not full-fledged programmes (Englund Dimitrova, Citation2013). In 1986, the Institute of Translation and Interpreting Studies at Stockholm University was established, with one of its tasks being to organise higher translator education in Sweden. Even before that, though, there had been some university-level programmes of 2–3 semesters. In the late 1990s, following Sweden’s accession to the European Union in 1995, translator education began in Lund, Gothenburg and Uppsala. Today, most translator programmes are offered at the MA level at Stockholm University, Lund University and Linneaus University. Currently, the only BA-level programme is offered at the Institute of Translation and Interpreting Studies at Stockholm University.

In Finland, translators’ associations are well established: The Finnish Association of Translators and Interpreters (SKTL) was founded in 1955 and The Language Specialists in Finland (Kieliasiantuntijat) in 1979. SKTL has sections for literary, business and audio-visual translators, and interpreters, as well as for teachers and researchers. The majority of its 2,500 members are freelancers. The 3,000 members of Language Specialists more often work as salaried employees: translators, interpreters, technical communicators or other language professionals. Recently, the Union of Journalists in Finland has also established sections for literary and audio-visual translators.

In Sweden, translators with different specialisations are more clearly organised in separate associations. The largest translator association is the Association of Professional Translators (SFÖ, est. 1990) with some 1,500 members who are mainly freelance business translators. Authorised translators, audio-visual translators and literary translators have their own organisations: The Association of Authorised Translators (FAT, est. 1932), The Audio-Visual Translators (est. 2013), and the translation section of The Swedish Writers’ Union, respectively. Only the Audio-Visual Translators and the Swedish Writers’ Union deal with union-related matters, the former as a part of the journalist’s trade union. Literary translators can also become members of the interest organisation The Translation Centre (est. 1979).

As illustrated by this brief summary, translation plays a major role in both Finland and Sweden, but that role has been more pronounced in Finland, and Finland also has a longer history of translator education and translators’ associations.

3. Material and method

The data for this study were collected by means of two electronic surveys on translator status. The Finnish dataset (n = 450) was collected in October–December 2014 by Ruokonen in collaboration with Leena Salmi, Tiina Tuominen and Taru Virtanen; an ethical review was not necessary at the time as no personal, identifiable data were collected, but all respondents indicated their informed consent. The Swedish dataset (n = 373) was collected in May 2016 as a part of a doctoral project (Svahn, Citation2020, pp. 33–35). Prior to the collection, the project was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, and all respondents indicated their informed consent (for more information, see Svahn, Citation2020, p. 35).

The surveys were based on Dam and Zethsen’s (Citation2008, Citation2011) questionnaires for Danish business translators and were adapted for three types of translators: freelancers, employed translators, and persons who were not working as translators at the moment (due to, e.g., parental leave). In this article, we focus on the first two groups. The Finnish dataset analysed therefore consists of 397 respondents and the Swedish dataset of 359 respondents.Footnote1 A comparison with Dam and Zethsen’s data was also considered but decided against as the bulk of the Danish data was collected in 2007–2009, antedating the Swedish dataset by seven years or more.

Selected background information about the respondents is presented in below.

Table 1. Respondents’ backgrounds.

The two datasets are similar in terms of gender, employment status and specialisation. In both datasets, most of the respondents are female freelancers, although the proportion of freelancers is more pronounced in the Swedish dataset. Similarly, most of the respondents are business translators, followed by literary translators and audio-visual translators.

As to differences, the Swedish dataset includes a higher proportion of older translators with longer working experience. This is reflected, firstly, in the fact that a larger proportion of the Swedish respondents work part-time (i.e., are probably partly retired). Secondly, it shows in the educational backgrounds: while over 70% of the Finnish respondents have a master’s degree and almost half of them have majored in translation, the Swedish respondents have more varied levels of education and only a quarter of them have studied translation. This may be due to the fact that Swedish translator education was established at a later stage than in Finland, with the result that the older participants did not have access to it.

Moving on to the variables analysed, the independent variable is the dataset, i.e., whether the responses come from the Finnish or the Swedish questionnaire. The dependent variables and the corresponding items are presented in . Most of the items concerned the respondents’ perceptions of translator status, expertise, etc. and were formulated to emphasise the respondents’ personal views, for example: ‘How do you perceive the degree of prestige attached to translation?’ or ‘In your opinion, does translating require expertise?’. However, some items prompted the respondents to consider how people outside the translation profession view the profession.

Table 2. Dependent variables.

If not otherwise indicated in the Results (section 4 below), the items relied on the following Likert-scale alternatives, also used in Dam and Zethsen’s questionnaires:

To a very low degree or not at all

To a low degree

To a certain degree

To a high degree

To a very high degree.

As in Dam and Zethsen’s questionnaires, the alternatives were given in the reverse order so as not to guide the respondents towards the lowest ranking (Dam & Zethsen, Citation2008, p. 78). For the analysis, the responses were converted into numerals from 1 to 5 as indicated above.

The data were tested in SPSS for statistically significant differences in the dependent variables between the Finnish and Swedish datasets. We used the Mann–Whitney U test to analyse the distributions of the various responses to the different items; the Mann–Whitney U test is suited for this type of comparison where the dependent variables are not normally distributed (Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2017, p. 100). A Chi Square test for homogeneity was considered but judged as less appropriate due to the skewed distributions of the responses (several expected frequencies would have amounted to 0.0; see Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2017, p. 170, p. 175).

4. Results

The results below are grouped into sections as follows: (1) statistically significant differences where the Finnish respondents’ rankings are higher; (2) statistically significant differences where the Swedish respondents’ rankings are higher; and (3) variables/items showing no significant differences. Concerning each item, we report the U value, the p value, mean rank, median, and mode for both groups. The mean rank represents the mean of the two datasets’ respective responses when ranked, making it an effective way to illustrate differences. The mode, i.e., the most recurrent response, indicates ‘the strength of the respondents’ preferences’ (Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2017, pp. 47–48).

4.1. Finnish respondents’ rankings significantly higher

The Finnish respondents’ rankings were significantly higher concerning overall status (one item out of two), education/expertise (four items out of eight), visibility (one item out of two) and power/influence (two items out of four). The details are given in above.

Table 3. Items with higher rankings for the Finnish respondents.

Translators’ status in society in general was regarded as slightly higher by the Finnish respondents (mean rank = 411.21 as opposed to 341.17 in the Swedish dataset), although both groups of respondents believed that the translation profession is accorded a ‘certain’ mid-level status (mode = 3 in both groups).

In contrast, the respondents’ views of the expertise, special skills and creativity required to translate accumulated towards 4 (‘high’) or 5 (‘very high’) in terms of medians and modes. However, the Finnish respondents considered translation a job requiring expertise to a higher degree (mean ranks: FIN 417.83, SWE 335.00), believed translation to require a higher degree of special skills (mean ranks: FIN 417.01, SWE 335.92), and thought that translation is more creative (mean ranks: FIN 405.64, SWE 348.4).

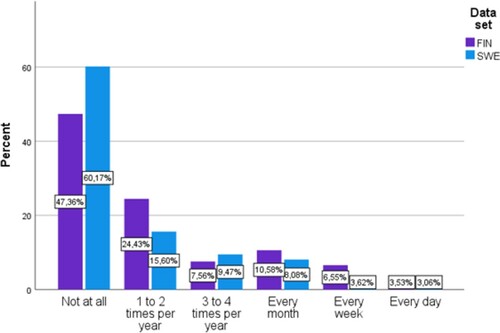

Concerning education, the respondents were asked to consider how many years of post-upper-secondary-school education people outside the field of translation would estimate as the length of translator education. The responses are illustrated in above.

Figure 1. Respondents’ views of the length of translator education as estimated by people outside the field.

As shows, most respondents across both datasets think that people outside the field would estimate the length of translator education as 1–2 years. There was nevertheless a significant difference: the Finnish respondents were slightly more prone to choose the options ‘3–4 years’ or ‘5–6 years’ than the Swedish respondents (mean ranks: FIN 386.74; SWE 353.96). Despite this statistically significant difference, both groups of respondents have the impression that people outside the profession underestimate the length of education required. In Finland, translator education is organised at the MA level, so the correct answer would have been 5–6 years. In Sweden, the situation is more complex, as there is at least one BA-level programme, but most translator education is offered at the MA level. However, as seen in , only 24% of the Swedish respondents have studied translation.

Similarly, translators’ visibility in society – phrased as ‘whether translators as a professional group are visible in society’ in the questionnaires – was seen as low in both groups, as illustrated by the medians and modes of 2. The Finnish respondents’ perceptions were, however, slightly higher (mean ranks: FIN 404.21, SWE 346.66).

Perhaps the most marked difference in the data concerns translators’ economic, political and other areas of influence. The Finnish respondents’ answers are fairly evenly distributed and over 45% of them characterise translators’ influence as high or very high. In contrast, almost half of the Swedish respondents see translators’ influence as very low. Similarly, while the Finnish respondents believe that people outside the profession see translators’ influence as low (median/mode = 2), the Swedish respondents typically selected the option ‘very low’ (median/mode = 1; mean ranks: FIN 391.61, SWE 355.15).

As we can see, there are some items concerning each variable (apart from income) where the Finnish respondents estimate translators’ status, expertise, visibility etc. as higher than the Swedish respondents do. However, there is so far no clear pattern. We therefore next look at the items where the differences point in the other direction.

4.2. Swedish respondents’ rankings significantly higher

The items where the Swedish respondents had higher rankings include education/expertise (two items out of eight), visibility (one item out of two) and power/influence (one item out of four). The details are given in .

Table 4. Items with higher rankings for the Swedish respondents.

Under education/expertise and concerning how the respondents believe people outside the profession view translators’ expertise, the medians and modes are the same for both datasets, indicating a ‘certain’ level of expertise. However, the Swedish respondents’ rankings are higher, both for expertise required to translate (mean ranks: FIN 361.72, SWE 393.03) and for special skills (mean ranks: FIN 361.51, SWE 396.28). This is an interesting contrast to the respondents’ self-perceptions of expertise, where the Finnish respondents’ rankings were higher.

Translators’ visibility, in the sense of feeling appreciated by commissioners and at workplaces, was high for both groups (median: 4). The Swedish respondents’ rankings are nevertheless significantly higher (mean ranks: FIN 338.37, SWE 421.72; modes: 4 and 5). As seen in the previous section, considering translators’ overall visibility, the situation was the opposite, with the Finnish respondents showing higher rankings.

Under the power/influence variable, both respondent groups regard the responsibility involved in translation as very high (medians/modes = 5), but there is a statistically significant difference in favour of the Swedish respondents (mean ranks: FIN 361.51, SWE 398.28).

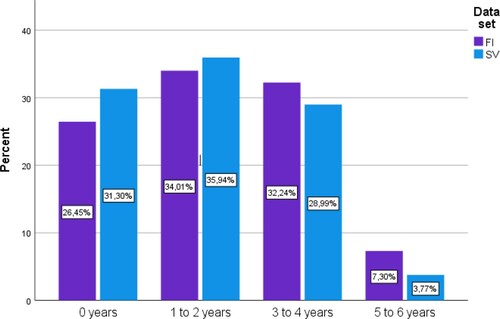

The respondents were also asked how frequently they had considered changing professions within the past year. The responses are illustrated in below.

As we can see, 60.17% of the Swedish respondents and 47.36% of the Finnish respondents replied ‘not at all’, which indicates that 39.83% and 52.64%, of the respondents, respectively, had considered leaving the profession at least a couple of times; the mode for both groups indeed corresponds to ‘1–2 times per year’. However, the Swedish respondents show a stronger commitment to the field than the Finnish respondents (mean ranks: FIN 400.34, SWE 354.35; medians FIN ‘1–2 times per year’ and SWE ‘Not at all’).

There is still no clear pattern emerging: the five items belong to four different variables, and there are no easily distinguishable connections between them.

4.3. No significant differences between Finnish and Swedish respondents

Finally, there are a number of items that did not yield any statistically significant results: one out of the two concerning overall status, the one item concerning income, and two items out of the eight concerning education/expertise. The details are compiled in .

Table 5. Items with no statistically significant results.

Regarding the overall status of the profession, the item on prestige yielded a non-significant result. Both the Finnish and the Swedish respondents have a similar – mid-level – view on the prestige attached to the profession (mean ranks: FIN 388.71, SWE 366.12; median/mode 3).

In terms of income, the two groups of respondents are equally satisfied with their income level (mean ranks: FIN 363.10, SWE 391.41), with a median of 3 (‘Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’) and a mode of 4 (‘Fairly satisfied’).

Under the variable of education/expertise, both Finnish and Swedish respondents firmly believe that their commissioners and workplaces have confidence in the quality of their translations (mean ranks: FIN 365.45, SWE 391.84; medians 5 and modes 4). Similarly, their perceptions of the status of the profession in society in comparison to other occupations of the same level of education are equally low (mean ranks: FIN: 377.02, SWE 373.79; medians/modes 2).

As in the two previous sections, there is no easily distinguishable pattern as to what did not yield statistically significant results. It can be noted, however, that there are two items that are close to being statistically significant: satisfaction with income level (p = .066) and, particularly, confidence by commissioners or at workplace (p = .058). In both these cases, the Swedish respondents have the higher rankings.

5. Discussion

Our results add to comparative research on translator status in cross-national contexts, which still remains scarce in Translation Studies. The central finding to emerge is the high number of items showing statistically significant differences; this clearly shows that there are differences in perceptions between the two cohorts of respondents, although previous preliminary comparisons based on published results highlighted the similarities (Svahn, Citation2020, pp. 84–92). After all, as shown in and , the medians and modes are often similar or even identical for the two groups, and the differences only become apparent at a statistical level. Together with Liu’s (Citation2021) study, the results here stress, firstly, the importance of systematically collecting comparable data from several national contexts, and, secondly, the relevance of comparing translators’ perceptions with statistical methods even in contexts that at first sight might appear similar.

Our results are also interesting because they highlight a number of apparent paradoxes. For example, the Finnish respondents’ rankings of translators’ expertise and special skills were higher than the Swedish respondents' and yet the Swedish respondents had a more positive outlook on outsiders’ perceptions of these aspects of the profession. Even more notably, the main variable – translator status – manifested paradoxical patterns. On the one hand, the Finnish respondents had higher perceptions of translators’ overall status and visibility in society; on the other hand, the Swedish respondents believed that they were more highly appreciated by commissioners or at their workplace and, thus, had higher perceptions of their status as individual translators (cf. Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018). Intriguingly, the item of prestige, commonly seen as an indication of status, showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups. There were also no differences in the item concerning translator status in comparison with other professions with the same level of education, which is particularly interesting as it does not seem to reflect the general differences in educational backgrounds: after all, a larger proportion of the Finnish respondents had completed an MA degree in translation.

Upon closer scrutiny, we distinguish two sets of macro-level factors that may explain the results: context-related and respondent-related factors.

Context-related factors include the longer tradition of Finnish translator education, the major socio-cultural role of translation in Finland, and the typological differences between Finnish and the respondents’ other frequent working languages (English and Swedish). These factors may explain the statistical differences where the Finnish respondents had higher rankings (see ). Firstly, the longer history of translator education corresponds to the larger proportion of Finnish respondents with translator education, which in turn may explain why the Finnish respondents had higher rankings in four items under the education/expertise variable: expertise, special skills, creativity, and outsiders’ view of educational length. Secondly, the socio-cultural role of translation in Finland, a bilingual country dependent on translations, may contribute to higher societal visibility, which may in turn highlight the importance of languages and translation in everyday life to a greater extent than in Sweden. This may have contributed to the Finnish respondents’ higher rankings in overall status, translators’ influence in society, and ‘outsider’ perceptions of translators’ influence in society. Finally, even typological differences between languages may play a role: as the majority of the Finnish respondents work with Finnish and English or with Finnish and Swedish (Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, p. 12), they often need to depart from literal solutions to produce idiomatic translations, which may subtly affect how they perceive the expertise, special skills, and creativity involved in translation.

In contrast, the items where the Swedish respondents showed higher rankings (see ) are not as easily explained by context-related factors. Instead, we connect them to demographic, respondent-related factors: as observed in Section 3, the Swedish respondents include a larger proportion of translators with over twenty years of working experience and working part-time, possibly being partly retired. In principle, longer experience could induce cynicism, but these data rather suggest the opposite: that the Swedish translators with longer experience are also feeling highly appreciated at work and that this sense of being appreciated carries over to how they view outsiders’ perceptions of translators’ special skills and expertise. Similarly, under power/influence, the Swedish respondents felt translation entails a higher degree of responsibility and were more committed to translation as a profession than the Finnish respondents. Changing careers may naturally be less likely for someone who is close to retirement, but this sense of responsibility indicates that the senior translators also feel highly invested in their work. Interestingly, although longer work experience may enhance translators’ sense of being appreciated at work, it doesn’t seem to affect their overall status perceptions (similarly to previous findings concerning the Finnish respondents; Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018, p. 12).

On the whole, the results thus highlight the need for both further cross-national comparisons and for a closer look into the multiple factors that influence translators’ status perceptions, such as gender, professional experience and educational background. For example, while the present analysis indicates that translator education may play a major role in macro-level comparisons between countries, further investigation into the role of education is required. Previous research has, on the contrary, failed to indicate statistical differences depending on educational backgrounds (Ruokonen & Mäkisalo, Citation2018; Svahn, Citation2020), apart from one item: the Swedish respondents’ rankings of their commissioners’/colleagues’ confidence in the quality of their translations, which were higher for those respondents with translator education (Svahn, Citation2020, p. 83). Similarly, the juxtapositions among the various status items, from translators’ overall status in society and prestige to appreciation at work, appear worthy of further attention. It will also be of interest to see whether the proposed links between feeling appreciated at work to perceptions of expertise and power/influence can be confirmed.

6. Conclusion

In the present article, we have investigated Finnish and Swedish translators’ perceptions of status and the related variables of income, expertise/education, visibility and power/influence. A comparative analysis of survey data revealed statistically significant differences in most items, which highlights the importance of further cross-national comparative analyses in the future.

While the results do not lend themselves to a straightforward interpretation based on the respondents’ nationalities, some of the differences can be attributed to the influence of the Finnish context with its longer history of translator education and more pronounced role of translation. Other differences may depend on the Swedish respondents’ longer professional experience. This opens two interesting avenues for further research. On the one hand, a closer examination is needed of how translators’ status perceptions are influenced by factors such as gender, professional experience and educational background. On the other hand, we also need a clearer understanding of the links between the various forms of status, prestige and appreciation and the variables of income, expertise/education, visibility and power/influence. In both cases, the analysis should ideally take multiple background factors into account and be performed on comparable data from different national contexts. The present paper has illustrated that studying apparently similar data can highlight interesting differences, which suggests that considering contexts that are culturally, economically and geographically more widely apart should also be fruitful. Addressing such a multitude of aspects may require complex analysis and modelling, but the results should take us closer to fully understanding the determinants of translator status.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Minna Ruokonen

Minna Ruokonen is a university lecturer in English Language and Translation at the University of Eastern Finland. She has collaborated on three extensive surveys among Finnish translators and translation students on their perceptions of translators' status and working conditions. Her other research interests include literary translation, particularly allusions, and the development of translation teaching.

Elin Svahn

Elin Svahn holds a PhD in Translation Studies from the Institute of Interpreting and Translation Studies at Stockholm University where she currently works as a senior lecturer. Her PhD focuses on extratextual translatorship and includes an extensive survey on Swedish translators' status perceptions. Following her PhD, she has also worked on translators' job satisfaction and retranslation.

Notes

1 In the Swedish questionnaire, the respondents were able to proceed in the questionnaire without answering all items, which means that the number of respondents may be lower for individual items.

References

- Andersen, T. M., Holmström, B., Honkapohja, S., Korkman, S., Söderström, H. T., & Vartiainen, J. (2007). The Nordic model: Embracing globalization and sharing risks. Helsinki: The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy (ETLA). Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://www.etla.fi/en/publications/b232-en/

- Axelsson, M. (2016). ‘Kalla mig inte mamsell!’: En jämförelse av tre skandinaviska översättares behandling av kulturspecifika element i fransk- och engelskspråkig skönlitteratur [‘Don’t call me miss!’: A comparison of three Scandinavian translators’ strategic choices in the translation of culture-specific elements in French and English novels]. Retrieved February 1, 2021, from http://uu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A916173&dswid=8094

- Chesterman, A. (2009). The name and nature of translator studies. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 42, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v22i42.96844

- Dam, H. V., & Zethsen, K. K. (2008). Translator status: A study of Danish company translators. The Translator, 14(1), 71–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13556509.2008.10799250

- Dam, H. V., & Zethsen, K. K. (2009). Who said low status? A study on factors affecting the perception of translator status. Journal of Specialised Translation, 12, 2–36. Retrieved May 5, 2017, from http://www.jostrans.org/issue12/art_dam_zethsen.pdf

- Dam, H. V., & Zethsen, K. K. (2011). The status of professional business translators on the Danish market: A comparative study of company, agency and freelance translators. Meta: The Journal des traducteurs / Meta: Translators’ Journal, 56(4), 976–997. https://doi.org/10.7202/1011263ar

- Dam, H. V., & Zethsen, K. K. (2012). Translators in international organizations: A special breed of high-status professionals? Danish EU translators as a case in point. Translation and Interpreting Studies, 7(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.7.2.07dam

- Dam, H. V., & Zethsen, K. K. (2013). Conference interpreters — the stars of the translation profession? Interpreting: International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting, 15(2), 229–259. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.15.2.04dam

- Englund Dimitrova, B. (2013). Översättarutbildningar i Sverige [Translator education in Sweden]. In I. Almqvist (Ed.), Från ett språk till ett annat. Om översättning och tolkning (pp. 66–70). Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Gentile, P. (2013). The status of conference interpreters: A global survey into the profession. Rivista internazionale di tecnica della traduzione, 15, 63–82. Retrieved December 11, 2020, from https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/10608

- Institute for Language and Folklore. (2020). Språkpolitik [Language policy]. Retrieved January 29, 2021, from https://www.isof.se/sprak/sprakpolitik.html

- Institute for the Languages in Finland. (2013). Kielet [Languages]. Retrieved February 20, 2021, from https://www.kotus.fi/kielitieto/kielet

- Katan, D. (2009). Translation theory and professional practice: A global survey of the great divide. Hermes – Journal of Language and Communication Studies, 42, 111–153. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v22i42.96849

- Lehikoinen, L., & Kiuru, S. (1991). Kirjasuomen kehitys [The development of written Finnish]. Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Leppänen, S., Pitkänen-Huhta, A., Nikula, T., Kytölä, S., Törmäkangas, T., Nissinen, K., Kääntä, L., Räisänen, T., Laitinen, M., Pahta, P., Koskela, H., Lähdesmäki, S., & Jousmäki, H. (2011). National survey on the English language in Finland: Uses, meanings and attitudes. Studies in variation, contacts and change in English 5. Retrieved July 11, 2021, from https://varieng.helsinki.fi/series/volumes/05/

- Lilius, P. (2003). Suomennoshistorian pohjoismainen perintö [The Nordic legacy of translations into Finnish]. In P. Lilius, & H. Makkonen-Craig (Eds.), Nerontuotteita maailmalta: näkökulmia suomennosten historiaan (pp. 23–45). Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Lindqvist, Y. (2002). Översättning som social praktik. Toni Morrison och Harlequinserien Passion på svenska [Translation as social practice. Toni Morrison and the Harlequin series Passion in Swedish]. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Lindqvist, Y. (2016). The Scandinavian literary translation field from a global point of view: A peripheral (sub)field? In S. Helgesson, & P. Vermeulen (Eds.), Institutions of world literature: Writing, translation, markets (pp. 174–187). New York: Routledge.

- Liu, C. F. (2021). Translator professionalism in Asia. Perspectives, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2019.1676277

- Mellinger, C. D., & Hanson, T. A. (2017). Quantitative research methods in translation and interpreting studies. London: Routledge.

- Munday, J. (2016). Introducing translation studies: Theories and applications (4th ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Parkvall, M. (2016). Sveriges språk i siffror. Vilka språk talas och av hur många? [Sweden’s languages in numbers. Which languages are spoken and by how many?]. Stockholm: Morfem.

- Parkvall, M. (2018). Arabiska Sveriges näst största modersmål [Arabic Sweden’s second biggest mother tongue]. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://www.svd.se/arabiska-sveriges-nast-storsta-modersmal/av/mikael-parkvall

- Ruokonen, M. (2013). Studying translator status: Three points of view. In M. Eronen, & M. Rodi-Risberg (Eds.), Point of view as challenge. VAKKI publications 2 (pp. 327–338). Vaasa: University of Vaasa. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from http://www.vakki.net/publications/no2_fin.html

- Ruokonen, M. (2018). To protect or not to protect: Finnish translators’ perceptions on translator status and authorisation. HERMES - Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 58(58), 65–82. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://tidsskrift.dk/her/issue/view/7564. https://doi.org/10.7146/hjlcb.v0i58.111673

- Ruokonen, M. (2019). Idealism or cynicism? A statistical comparison of Finnish translation students’ and professional translators’ perceptions of translator status. MikaEL, 12, 104–120. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://www.sktl.fi/liitto/seminaarit/mikael-verkkojulkaisu/arkisto-archive/mikael-vol-12-2019/

- Ruokonen, M., & Mäkisalo, J. (2018). Middling-status profession, high-status work: Finnish translators’ status perceptions in the light of their backgrounds, working conditions and job satisfaction. The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 10(1), 1–17. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from http://www.trans-int.org/index.php/transint/issue/view/44. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.110201.2018.a01

- Setton, R., & Guo Liangliang, A. (2011 [2009]). Attitudes to role, status and professional identity in interpreters and translators with Chinese in Shanghai and Taipei. In R. Sela-Sheffy, & M. Shlesinger (Eds.), Identity and status in the translational professions (pp. 89–117). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Sevänen, E. (2007). Suomennoskirjallisuuden määrällisestä kehityksestä [Quantitative changes in literature translated into Finnish]. In H. K. Riikonen, et al. (Eds.), Suomennoskirjallisuuden historia 2 (pp. 12–22). Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Sook Kang, M., & Shunmugam, K. (2014). The translation profession in Malaysia: The translator’s status and self-perception. GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies, 14(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.17576/GEMA-2014-1403-12

- Svahn, E. (2020). The dynamics of extratextual translatorship in contemporary Sweden: A mixed methods approach [Dissertation]. Stockholm University, Stockholm. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-177365

- Svahn, E., Ruokonen, M., & Salmi, L. (2018). Boundaries around, boundaries within: Introduction to the thematic section on the translation profession, translator status and identity. Hermes: Journal of Language and Communication in Business, 58, 7–17. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://tidsskrift.dk/her/issue/view/7564

- Treiman, D. J. (2001). Occupations, stratification, and mobility. In J. R. Blau (Ed.), The Blackwell companion to sociology (pp. 287–313). Malden, Mass and Oxford: Blackwell.

- Virtanen, T. (2020). What makes a government translator tick? Examining the Finnish government English translators’ perceptions of translator status, job satisfaction and the underlying factors [Dissertation]. University of Helsinki, Helsinki. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-51-5535-1

- Wivolin, S. (2012). II jaoston taustatietokysely – loppuraportti [Survey of the SKTL business translators’ section]. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from members-only website at https://www.sktl.fi/jasenet/asiatekstinkaantajat/tulotasokyselyt/