ABSTRACT

The aim of this essay is to explore the hypothesis that inter-peripheral literary circulation is achieved through support from institutional funders who are situated outside the target culture and mainly in the source culture – so called ‘supply-driven translation’. By focusing on Swedish translations of Italian and Portuguese (Angola, Cabo Verde, East Timor, Mozambique, and Portugal) language literatures this study investigates whether support from the source culture provides an alternative pathway for this literature to make its way into the hands of Swedish readers, including scholars. First, this study reviews the available funding for this literature and maps out which publishing houses, authors, and titles received financial support between 2000 and 2018. The analysis focuses on the support from institutions that are closely related to two of the source countries (Italy and Portugal) and addresses questions regarding the prestige and gender of the supported authors, the size of the publishing houses, previous translations into English, and how this support influences visibility in the public literary sphere and in the Swedish press. Translations and publications of Portuguese language literatures depended on and received financial support, whereas translations and publications of Italian literature were largely produced without any financial support. However, in many respects, the source languages show striking similarities.

1. Introduction

How does literature circulate within the periphery? A comprehensive answer to the question should consider several aspects of cultural mediation and power relations, from the sole translator/publisher who translates/publishes for the passion of a particular text to the international industry surrounding bestsellers. In this essay, we explore the hypothesis that inter-peripheral literary circulation is achieved due to initiatives and financial support from national and international funders. Drawing on van Es and Heilbron’s (Citation2015) observation that analyses of the circulation in the global literary field tend to ignore the impact of subsidies, we investigate the institutional support given to literature written in Italian and Portuguese and translated into Swedish.

The importance of institutional funding is also stressed by Gisèle Sapiro and Johan Heilbron in a study that examines cultural export policies relating to translations of Dutch and Hebrew literature. They claim that ‘[f]or peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, the very existence and visibility of their national literature on the international scene depends on such policies’ (Citation2018:, p. 185).

Our study focuses on so called ‘supply-driven translation’, which, according to Ondřej Vimr, occurs when the supplier comes from outside the target culture, mainly from the source culture. This view complements Gideon Toury’s more traditional understanding of literary circulation as ‘demand-driven’ (Vimr, Citation2020, pp. 49–52). Vimr also claims that more research on the support of translations is needed ‘especially in the area of inter-peripheral relations’ (Citation2020:, p. 60). Following the works of van Es and Heilbron (Citation2015), Sapiro and Heilbron (Citation2018), and Vimr (Citation2020), we explore whether translation publishing grants are crucial for elevating Italian and Portuguese (Angola, Cabo Verde, East Timor, Mozambique, and Portugal) language literatures into Swedish. Even though we start by mapping out the possibilities that these literatures have to achieve support in the target culture (Sweden), the aim of our investigation is to highlight the importance of funders in the source cultures. In Portugal, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs offer two grants to support the international publishing and dissemination of works by Portuguese-language authors from Portugal, Africa, and Asia, but they do not support the works of Brazilian writers. Therefore, this study includes Portuguese language literatures from Africa and Asia while Brazilian literature falls outside its scope. However, given the fact that these funders support translations of literature written in Portuguese from different countries (former colonies), the analysis makes several remarks on the support policies deriving from different geographically peripheral positions. A different situation applies to Italian literature which is supported by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and a local funder, the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation, which is closely related to the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm. The latter supports applications from Italian and Swedish publishing houses, while the former supports the translations of Italian literature into foreign languages.Footnote1

From a global point of view, all the literatures that we focus on in this study could be defined as peripheral. There are however various ways of considering the peripherality of a specific literature. According to Heilbron (Citation1999) and van Es and Heilbron (Citation2015), the peripheral status should be understood as a low share of translations on a global scale. In this perspective, Swedish and Italian are regarded as semi-peripheral languages in the global translation exchange, since they account for 1-3 percent of the translations worldwide, while Portuguese, together with many other globally widespread languages, is classified as peripheral because it represents less than 1 percent of the international translation market (Heilbron, Citation1999). We argue however that Portugal’s position in the global circulation is far more complex and that there are alternative ways of conceiving the notion of semi-peripheral that need to be considered. For example, semi-periphery could be defined as a geographical position of intermediation and transfer of cultural goods and literature. In the field of Portuguese Translation Studies, the assumption of Portugal being semi-peripheral is based on the position of Portugal, and the Portuguese language, as a centered mediator between different cultures and literatures, both inside the Portuguese-speaking circuit as well as between Europe and Africa, South America, or Asia. Furthermore, in this perspective, the Portuguese literary system is divided between a central position in relation to its own former Portuguese-speaking colonies and a ‘peripheral position within the European context’ (Maia et al., Citation2015: xix). This view requires a comprehension (and a usage) of the classifications of ‘center-semiperiphery-periphery’ as non-static entities that depend on inter-relational cultural connections (historical, political, economic, and social) between the source and target cultures in question.

Moreover, we argue that it is important to address the local and interrelational aspects of literary exchanges. In this perspective, the number of editions of Portuguese language literature that are translated into Swedish annually (4-10 titles) is lower than the number of Italian editions translated into Swedish (30-35 titles). According to statistics published by the National Library of Sweden (Citation2021), Italian was the seventh most common source language in the years 2018-2020. In 2020, only four editions were translated from Portuguese, which ranks the language as one of the sixteen most translated together with Czech, Korean, Persian and Slovenian (National Library of Sweden, Citation2021, p. 19). These numbers indicate that Italian literature enjoys a more central position in the Swedish book market than does literature from the Portuguese language.

Here, we compare the available funding for the translation flows (from Angola, Cabo Verde, East Timor, Italy, Mozambique, and Portugal to Sweden) and analyze the titles and publishing houses that received financial support between 2000 and 2018. To discover the degree to which the chosen literatures depended on subsidies from the source cultures, the analysis addresses the following questions: How many translations into Swedish received financial support during the studied period? What kind of literature received support? Is it true, as is generally suggested, that the supported titles and the publishers in the target culture belong to small-scale production (cf. van Es & Heilbron, Citation2015)? What did the gender balance look like? Were supported titles translated into more central languages before reaching Sweden or did the support provide an alternative and direct way for connecting these cultures? The final step of the analysis considers the effects of the support: Were the supported writers invited to Sweden to promote their work? Did they receive any attention in the Swedish press?

2. Funders – an overview

Considering the whole map of possibilities for achieving national and international support, the following funders supported translations from Italian and Portuguese (from the areas specified above) into Swedish: The Creative Europe Programme of the European Union; CitationThe Swedish Arts Council (Statens Kulturråd); The Portuguese General Directorate for Book, Archives and Libraries (Direcção-Geral do Livro e das Bibliotecas); The Portuguese Cultural Institute, Camões (Camões Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua); The Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs; and The C.M. Lerici Foundation (Fondazione C.M. Lerici). Although this study focuses on the latter four funders – that represent the supply side – we start with a presentation of the former two.

2.1. Creative Europe Programme of the European Union

In 2014, The Creative Europe Programme of the European Union began to support the European audiovisual, cultural, and creative sector, including literary translation. According to its website, the literary translation scheme aims ‘to promote the transnational circulation of literature and its diversity in Europe and beyond and to expand the readership of quality translated books’ (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/creative-europe_en). Publishers and publishing houses can apply for the grant to support the translation, publication, and promotion of a package of three to ten literary works written in or translated into officially recognized EU languages. The scheme especially encourages the translation of books from and into ‘lesser used languages into English, French, German or Spanish’ to increase the visibility of the books in Europe and beyond. For this reason, the inter-peripheral exchange that we are dealing with in this study is not the scheme’s highest priority. Swedish as a target language was selected only three times (2014, 2015, and 2016), and in two cases there was an Italian title included in the package.

Norstedts, one of Sweden’s largest publishing houses, received grants three times. On two occasions, Italian titles were among those that received grants, and both times the grants went to Elena Ferrante’s bestselling Neapolitan Novels.Footnote2 That is, the support of Italian literature translated into Sweden went to works and a publisher close to the commercial pole. No support was given to literature translated into Swedish with Portuguese as its source language, which might be explained by the grant policy of targeting lesser used languages and the editorial circumstances for this literature. Most Swedish publishers are small with an irregular publication rate and therefore would have difficulty matching the program’s requirements for a publication series of three to ten books.

2.2. An institutional funder in the target culture

Although this study focuses on support from institutions representing the source languages’ literatures, funding can be applied for in the target country as well. The main institutional funder of translations in Sweden is CitationThe Swedish Arts Council (Statens Kulturråd), which controls and administers an important support system for publishers of translated literary works. The grant Literature Support (litteraturstöd) is available for publishers that can guarantee their books will be distributed through established channels such as libraries and booksellers. The support, which currently amounts to a maximum of 70,000 Swedish crowns (about 7000 EUR), can only be requested for publishing a first edition or for republishing classic literature. On their web page, The CitationSwedish Arts Council describes their grants as a way to ensure that ‘more people can have access to a varied range of high-quality literature throughout Sweden’ by prioritizing translations that contribute to diversity and from languages seldom translated.Footnote3 To examine the impact of this institutional funder in the target culture, we have determined the number of titles that received support between 2004 and 2018.

The Swedish Arts Council supported 28 Portuguese titles (52%) of 54 published titles.Footnote4 The publishing houses receiving support range from large-scale to small-scale. Large-scale publishing houses like Wahlström & Widstrand and Forum, both belonging to the Bonnier Group, received support to publish the Portuguese Nobel Prize laureate José Saramago and the possible Nobel candidate António Lobo Antunes. Leopard, a mid-scale publisher, received support to publish translations of the contemporary and globally renowned authors Mia Couto (Mozambique) and José Eduardo Agualusa (Angola). However, most of the publishers that received support were small. Here, we find publishers specialized in translations of poetry, some highly consecrated poets in their source cultures, including Sophia de Mello Breyner (Portugal), Vasco Graça Moura (Portugal), and José Craveirinha (Mozambique). Niche publishers received support for translating highly praised contemporary novelists such as Gonçalo M. Tavares (Portugal), Pepetela (Angola), Ondjaki (Angola), and Luis Cardoso (East Timor), and the canonized Portuguese modernist poets Fernando Pessoa and Mário de Sá-Carneiro. Interestingly, the Modernista Group republished four of António Lobo Antunes' novels, which all received support supposedly for qualifying as republished classics. Otherwise, most of the titles are first editions of highly respected authors in their source cultures. The Swedish Arts Council’s support is distributed to the whole publishing market for literature from large-scale to small-scale publishers and equally for poets as for novelists. Astonishingly, only one of the 28 supported titles was authored by a woman, the poet Sophia de Mello Breyner. Two of the titles are anthologies with authors of mixed genders.

The Swedish Arts Council supported (litteraturstöd) 58 (23%) of the Italian titles published between 2004 and 2018, which is a significantly lower share than the share of titles translated from Portuguese. On the other hand, in terms of actual figures, 58 titles translated from Italian is more than twice as many titles translated from Portuguese (28).

Among the chosen titles, a remarkably high share (36%) of the works could be defined as older classics such as works written by Boccaccio, Petrarch, Michelangelo, Foscolo, and Leopardi and modern classics such as works written by Luigi Pirandello, Primo Levi, Italo Calvino, Giorgio Bassani, and Natalia Ginzburg. Most of the supported titles, however, were contemporary authors – e.g. Umberto Eco, Dario Fo, Alessandro Baricco, Melania Mazzucco, Valerio Magrelli, Claudio Magris, and Paolo Cognetti. Interestingly, many authors had previously been translated into Swedish, a selection strategy based on what Hanne Jansen calls ‘inertia’ (Jansen, Citation2019, p. 49). Only 21% of the supported titles were written by women, the same gender division for Italian authors in Swedish translation (Schwartz, Citation2021).

The publishing houses that received support were mainly small publishers although 20% of the supported titles were published by some of the largest publishing houses in Sweden (Bonniers, Natur & Kultur, Norstedts, Wahlström & Widstrand).

2.3. Institutional funders in the source system

Here, we will briefly describe the national funders of Italian and Portuguese literature abroad, especially the subsidies available to Swedish publishers. The comparison between the resources available for the two languages shows some striking differences.

In Portugal, the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs offer two grants to support the international publishing and dissemination of works by Portuguese-language authors from Portugal, Africa, and Asia: the General Directorate for Book, Archives, and Libraries (Direcção-Geral do Livro e das Bibliotecas) (DGLAB), which offers translation grants to publishers, and the Portuguese Cultural Institute, Camões (Camões Instituto da Cooperação e da Língua) (Camões), which offers grants for publications. Publishers apply for these grants directly through the organizations’ head offices in Portugal. The ‘translation publishing grant’ from DGLAB makes the greatest impact on the total number of translations published in Swedish. This grant, a maximum of 6000 EUR, can cover up to 60% of the total translation cost, but in low-cost countries it can cover more than 60%. The grant is awarded to all applicants irrespective of the size of the publisher or the author’s status.Footnote5 Therefore, the publishers are responsible for title selections as they do not need to conform to special directives. In contrast, Camões’ publishing grant does not specify costs or guarantee publication support and therefore has a smaller impact on the number of translations published in Sweden. As the following discussion focuses on the support the Portuguese state provides Swedish publications, these two grants will be considered together.

The publications receiving Portuguese support between 2000 and 2018 include authors from Portugal, Africa (Mozambique, Angola, and Cabo Verde), and East Timor. DGLAB together with the Camões Institute have made available a database with information about these published translations abroad which is available through their website and includes information on what kind of support the publications received.Footnote6 The grants are only distributed after the work has been published (to make sure of publishing) and the publisher must agree to include the institute’s logo and an acknowledgment of the institute’s funding in the book. In addition, the publisher must agree to send several copies of the translated book to the institute.

Swedish publishers can apply for subsidies from the Italian state (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) and from a local funder, the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation.Footnote7 Applications for both these grants have to go through the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm. Since the information of which titles have received subsidies from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was not available (not even after two requests from the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm), the Italian part of this research relies on the subsidies distributed by the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation between 2000 and 2018. However, of all the Italian literature translated into Swedish in 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015, only one received support from the Italian Foreign Ministry.Footnote8

In Sweden, the main funder of translations from Italian is the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation, which is closely related to the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm – the director of the Institute is also the chairman of the board of the foundation. The Italian Cultural Institute reports to the Italian Embassy and therefore to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Footnote9 This arrangement means that what is being supported depends largely on the source culture and therefore is a case of supply-driven translation. A list of the subsidies distributed by the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation was compiled on our request by an intern at the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm.Footnote10 The list was subsequently published on the foundation’s webpage.Footnote11

Both Swedish and Italian publishing houses can apply for the grant, but priority is given to publications that promote the cultural exchange between Italy and Sweden (works in Swedish about Italy or Italian issues and vice versa). The grant, a maximum of 50,000 Swedish crowns (about 5000 EUR), covers costs for translation and publication. The grant requires the publisher to provide the Foundation with ten copies of the book and to include the phrase ‘published with support from the Foundation C.M. Lerici’ in English or in Italian in the book. The grants can be awarded for translations of non-literary works. Between 2014 and 2018, according to the Foundation’s website, 20% of the grants were awarded to literary works and 80% were awarded to scientific works including the natural sciences, humanities, economics, architecture, art, and music (https://www.cmlerici.se/). According to the statistics published on the webpage, five to ten titles received a literary grant between 2014 and 2018, totaling to 300,000–400,000 Swedish crowns (about 30,000–40,000 EUR).

3. Analysis of the literary support from institutional funders in the source system

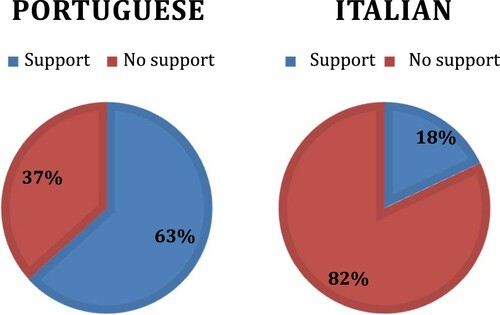

shows the total translations of Italian and Portuguese literature (from Portugal, Africa, and East Timor) into Swedish and the financial support they received.

Between 2000 and 2018, 43 (63%) titles of the 68Footnote12 translations from Portuguese (Portugal, Africa, and East Timor) into Swedish received financial support: 25 (62%) of 40 translated works from Portugal, 18 (72%) of 25 from Africa, and three (100%) of three works from East Timor (all works of Luis Cardoso). Clearly, the works of African and Asian writers received a higher percentage of publication support compared to Portuguese writers, although the overall high percentage of support for all these literatures is evident.

During the same period, the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation provided translation support for 50 (18%) of the 278 titles translated from Italian into Swedish.Footnote13 The distribution per year shows that the number varies from zero to eight titles with an average of 2.7 titles per year.

In summary, a comparison between our two source languages underscores that the Portuguese support policies for translations from these Portuguese language literatures into Swedish are significant, whereas grants from the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation turned out to have less impact on the literary circulation of Italian literature in Sweden.

3.1. The supported publishing houses and literature

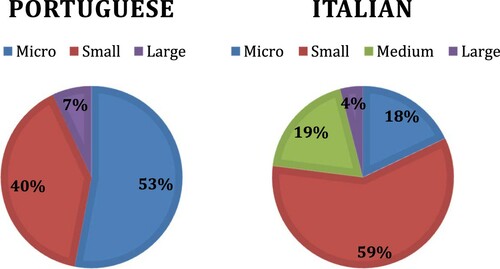

provides an overview of the size of the publishing houses.

Between 2000 and 2018, 15 publishers received Portuguese translation and publishing grants. Overall, these publishers were small-scale publishers (40%) or even ‘micro publishers’ (53%).Footnote14 Moreover, the majority of these micro publishers specialize in poetry, less known languages, or Portuguese-language literatures. There are also some small but established publishers that received support for translating literature from territories outside Western locations and for other genres, for example, children’s literature.Footnote15 The only exception to the rule is the large publisher Wahlström & Widstrand, which received support for translating the novel Klarsynen (Ensaio sobre a Lucidez) by José Saramago. However, small and micro publishers published the most titles: Almaviva (11 titles), Tranan (10 titles), Pontes (4 titles), and Panta rei (4 titles). Almaviva and Panta rei, specializing in literature written in Portuguese, seem to have established a relationship with DGLAB as they received support for all their published titles during this period. This pattern of small and micro publishers receiving support from the Portuguese Institutes is reflected in the fact that titles that did not receive support were mainly published by mid and large publishers.Footnote16 Instead, as we have seen above in section 2.2, the mid and large publishers received substantial support from the Swedish Arts Council. Furthermore, 12 of the titles supported by the Portuguese Institutes also received grants from this national agency in the target culture.

Shifting focus to the literary works and authors who received Portuguese support, the picture that emerges shows that titles from highly respected authors in their source cultures were selected. For example, Portuguese support was given to one globally circulated and well-known Angolan writer, Agualusa, two of the Portuguese canonized modernist writers, Fernando Pessoa and Mário de Sá-Carneiro, and one of the most critically acclaimed and bestselling authors from Portugal, Gonçalo M. Tavares. Moreover, two of Saramago’s novels were also supported, and the titles from José Saramago published by a large publisher were supported by the Swedish funder. The same is the case for renown authors António Lobo Antunes and Mia Couto. Their publications did not receive support from Portuguese funders, but they did receive support from the Swedish Arts Council. Grants from Portuguese funders largely supported small publishers, whereas grants from the Swedish Arts Council largely supported mid and large publishers. These examples show that Portuguese-speaking authors, even well-known and successful novelists and authors in their source cultures, depend on support to gain access to the Swedish book market.

In comparison with literature translated from Portuguese, the publishing houses that issued Italian literature were more varied (). During the study period, the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation provided money for translation support to 27 publishing houses: 59% were small publishers and 18% were micro publishers (i.e. almost 80% were small or very small). The main difference with regard to Portuguese is that some mid-size publishers (19%) received support. Only one (4%) large publisher received support, a highbrow project initiated by the publisher: the publication of Italo Calvino’s work. This, however, was an exception as the rest of the publishers were either medium, small, or micro.Footnote17

Several of the supported writers definitely belong to the large-scale pole, including Andrea Camilleri and Giorgio Faletti, both authors of crime fiction, and the authors of the graphic novels about Dylan Dog and Tex Willer. As in the case of Portuguese, some renowned writers such as the Nobel candidates Antonio Tabucchi and Claudio Magris, who both have been published in Sweden since the 1990s, received support. Even more unexpected is the fact that titles by worldwide bestselling authors such as Umberto Eco and Roberto Saviano received support from Lerici. In addition, many contemporary writers recognized by the Italian literary establishment but less known abroad all received support: Melania Mazzucco, Milena Agus, Marco Missiroli, Mauro Covacich, Valeria Parrella, Vitaliano Trevisan, Roberto Alajmo, Paolo Cognetti, Mario Rigoni Stern, Marta Morazzoni, and Igiaba Scego. To use Hanne Jansen’s terminology, this part really aimed at ‘innovation’, whereas the supported classics – two by Petrarch and Leopardi and six modern classics by Saba, Ungaretti, Pavese, Rodari, Morante, and Calvino – were from publishers who used ‘inertia’ as their selection strategy (Jansen, Citation2019, p. 49). The remaining category includes less known Italian writers and contemporary poets such as Luigi Mazzella, Luciano Erba, and Maura Del Serra. Therefore, we can conclude that the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation supports all kinds of literature in the source culture from crime fiction, via worldwide bestsellers, classics, well-known contemporary Italian authors, and lesser known authors. The emphasis, however, is on the category of consecrated contemporary Italian authors who could also be invited to the Italian Cultural Institute.

As in the case of literature funded by the Portuguese Institutes, there is a strong divide between the position of these authors in Italy and Sweden: in Italy they are consecrated by critics and published by the largest and most important publishing houses, but in Sweden they are unknown by critics and published by smaller publishers. This combination of funding small Swedish publishers for translating well-established authors from source countries indicates not only a lack of ‘horizontal isomorphism’, where publishers in the target culture tend to choose titles by publishers with a similar profile in the source culture (Franssen & Kuipers, Citation2013), but also a focus on authors from source languages, no matter how consecrated at home, by small or even very small publishers in Sweden.

3.2. Support and author’s gender

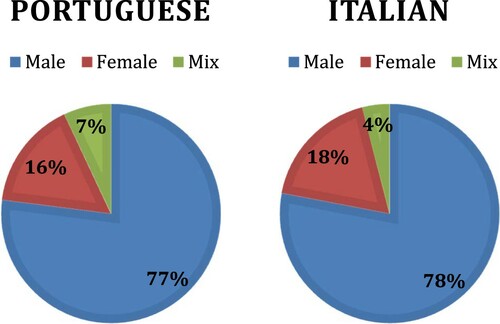

Gender is generally an under-researched area in the field of world literature and the transnational circulation of texts. Although much effort has been given to the exploration of how authors from peripheral regions, languages, and cultures move about the center (or vice versa), these studies have yet to foster gender analysis. Evidently, the author’s gender, on various levels, influences the odds of works crossing borders (cf. Atkin, Citation2020; Edfeldt, Citation2020; Schwartz, Citation2019, Citation2021). While the short format of this text does not allow us to conduct an in-depth gender analysis of the material, we still think it is important to discuss how many of the supported titles were written by women and how many were written by men.

reveals a striking gender imbalance with regard to support from both source languages. In the case of Portuguese, only seven (16%) titles authored by women were given grants and three (7%) titles were anthologies including both women and men. That is, 77% of the supported titles were written by men. An almost identical male bias can be observed in the case of Italian: 39 (78%) supported titles were authored by men and only nine (18%) titles by women (4% of titles were in volumes including both men and women).

To draw valid conclusions from this calls for an in-depth gender analysis including various levels of social interaction and institutions of circulation, from conditions for female creativity in their source culture to mediating institutions and cultural mediators in the target culture. Many of the translated works were written by the most famous male authors from each source culture, leaving little room for women authors no matter how celebrated and respected they are in their source culture.

3.3 Previous translations into vehicular languages

One of the common selection strategies defined by Jansen (Citation2019) is ‘imitation’–i.e. publishing houses tend to look at what is chosen for translation abroad. Because imitation is mainly applied by larger commercial publishers, our hypothesis was that support deriving from a source language culture would provide an alternative way for connecting semi-peripheral and peripheral cultures. To examine this issue, we checked whether the supported titles had been translated into English before reaching Sweden.

Consulting the database of translations provided by DGLAB on their webpage,Footnote18 we found that only 16% of the supported titles had been previously translated from Portuguese into English. However, many titles were compiled in volumes of short stories or poetry, which did not necessarily correspond to an original work. Therefore, it is more accurate to follow the poet’s translations into other languages. Among the 14 titles of poetry, authored by eight poets, only three Portuguese poets (Eugénio de Andrade, Núno Judice, and Fernando Pessoa) had been translated into English before being published in Swedish. In contrast, more of the Portuguese poets were translated into French and other Romance languages, suggesting a linguistic circulation for poetry written in the Romance languages. The Mozambican poet José Craveirinha does not have book-length translations into English or French. The same is the case for the Angolan poet Ana Paula Tavares, who was translated and published into Swedish by Gunilla Winberg (Panta rei), who previously worked in Angola. With respect to novels, which are easier to verify, ten (40%) titles of 25 funded novels were previously translated into English. The tendency is that some of the novels of the African writers (Agualusa, Ondjaki, and Pepetela) were published first in English, while children’s literature and poetry were not published first in English. Analyzed together with the demography of the publishing houses, we found that the chosen titles were more likely to have been a result of networking between individual cultural mediators in the source and target cultures supported by grants from Portugal.

Again, we see a similar situation in the case of the supported Italian titles: 13 of 39 titles (33%) had already been translated into EnglishFootnote19 and three (8%) titles were translated into Swedish the same year as they were translated into English.Footnote20 Interestingly, almost half of the cases of the volumes already translated into English had been translated several years before, which indicates that the Swedish translations in these cases should be understood as delayed translations, chosen to ‘fill the gaps’: Cesare Pavese’s Prima che il gallo canti (1956/2010), Leopardi’s Operette morali (1882/2012), Gianni Rodari’s Favole al telefono (1962/2002), Italo Calvino’s Il sentiero dei nidi di ragno (1947/2016), Mario Rigoni Stern’s Il sergente nella neve (1953/2002), and Umbero Saba’s Il Canzoniere (1948/2018).Footnote21 Consequently, these translations were not a consequence of imitation because they had been translated into English, but because they were regarded as modern classics in the source culture and not yet available in Swedish. If these titles are withdrawn from the 13 titles translated first in English, only seven (14%) titles remain and even among these remaining titles there are some cases that do not seem to be a consequence of an existing English translation.Footnote22 When it comes to French and other Romance languages, a similar pattern as the one we discerned in the case of Portuguese occurs with regard to Italian: many of the titles and authors who received support from the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation had previously been translated into a Romance language. Obviously, this has to do with closer cultural and linguistic contacts between the languages, but it is uncertain whether a translation into another Romance language influences Swedish publishers or funders such as the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation.

Our results clearly indicate that translations into the hyper-central language English is of very little importance for supporting the Swedish translation of our source languages. This finding suggests that the grants from the Italian and Portuguese funders provide an alternative way for interconnecting peripheral literatures. The fact that there are more translations into French and other Romance languages does not necessarily mean that this led to financial support; we suggest that this has to do with the existence of inter-Romance language literary circulation, a suggestion that merits further investigation.

3.4 The effects of the support: invitations and media attention

Being translated is not a guarantee that readers in the target culture will be reached (cf. Broomans & Jiresch, Citation2011). In fact, after a translation has been published some additional actions and activities are often required to stimulate interest, such as inviting authors to discuss their books and holding media events (i.e. conducting a publicity campaign).

The Camões Institute is the most important funder of cultural events regarding Portuguese-speaking cultures in Sweden. They provide publishing grants and support several language institutes and lecturers in Portuguese hosted by universities all over the world. One of these centers is located at Stockholm University. In addition to teaching activities, the lecturer also has a budget for organizing cultural events that aim to disseminate Portuguese-language culture abroad. The cultural budget has to be approved by the Portuguese embassy. Often, the Camões Institute invites authors of newly translated works who received publishing grants to promote their new book in Sweden. The writers are usually invited to events hosted by the university, targeting both students and an interested audience, and to the largest Swedish book fair in Gothenburg in September. In this way, the Camões Institute functions as an economic and logistical instrument that helps authors publicize their works in Sweden.

For the Italian authors supported by the CitationC.M. Lerici Foundation, half of the 36 authors who were possible to invite (in 14 cases the author was dead) visited Sweden through an invitation from the Italian Cultural Institute.Footnote23 This indicates a strong correlation between the publications granted by the Institute and the invited authors. Most of the authors were invited to present their translated title at the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm, but some authors were invited to participate in other events outside the Italian Cultural Institute – e.g. Antonio Tabucchi, who appeared in the program of ‘The Culture House’ (Kulturhuset) and visited Stockholm University soon after the publication of his supported title I volatili del Beato Angelico (1987/2010), which was also issued by the series Cartaditalia published by the Italian Cultural Institute.Footnote24

To examine the presence of the supported literature in the Swedish press, we searched an online newspaper archive, Artikelsök.Footnote25 Overall, the supported titles from both source languages had very limited coverage in the Swedish press. In the Portuguese case, this difficulty in attracting media attention was probably a consequence of the publishers’ position as small and micro publishers in the book market, where the mid and large publishing houses have received higher visibility. Nevertheless, some patterns are discernable. First, the media rarely reviewed poetry and anthologies. The exception to the rule concern the modernist Fernando Pessoa, arguably the most recognized Portuguese writer, published by the small publisher Pontes. His four titles were reviewed in the largest daily papers (e.g. Svenska Dagbladet, Dagens Nyheter, and Sydsvenskan) and in the literary magazine Bonniers Litterära Magasin. Pessoa also received the most scholarly attention in the form of special articles (7). There was greater press interest in the African authors (Ondjaki, Pepetela, and Agualusa) than in the Portuguese authors. Among these authors, the one receiving the largest interest in the form of reviews (between 7–10 reviews for each of his three titles) was the Angolan writer Agualusa, published by the micro publisher Almaviva. In addition, there seems to be a connection between a specific publishing house (perhaps via good reputation or connections) and the received attention. For example, the titles of the publishers Tranan and Almaviva were more often reviewed than their counterparts, and Pepetela was reviewed when published by Almaviva but not when published by another micro publisher, Panta rei.

In the case of Italian, the supported titles that attracted the most media attention were published in 2001–2002, mainly because of a title with poetry by Giuseppe Ungaretti (13 reviews), and titles by Andrea Camilleri, Gianni Rodari, and Mario Rigoni Stern were discussed in the press. A second peak occurred in 2010–2011, when several Italian writers were translated into Swedish and published in the series of the Italian Cultural Institute and by a new publishing house, Astor. The main attention, however, was drawn to Antonio Tabucchi, Claudio Magris, and Umberto Eco, three widely-known Italian writers whose translations in those years were promoted by their visits to Sweden, resulting in 12 interviews in the Swedish press. The number of mentions of translations in the press in 2010–2011 was 49; in 2012–2013, there were only five mentions in the press. All this indicates that there is a latent media interest in Italian writers, but this interest seems to be focused on established protagonists of the international literary field rather than new voices.

4. Concluding remarks

This study investigates the impact of financial support from institutional funders in the source systems of inter-peripheral literary circulation. Although a very large share of the analyzed Portuguese language literatures received support from national institutions in Portugal (and Sweden), most Swedish translations of Italian literature were published without subsidies. This result both confirm and contradict Sapiro and Heilbron’s claim that ‘[f]or peripheral and semi-peripheral countries, the very existence and visibility of their national literature on the international scene depends on such policies’ (Citation2018:, p. 188). On the one hand, the claim is contradicted in the case of Italian literature, which does not depend on subsidies for being translated into Swedish, but on the other it is confirmed in the case of all the Portuguese language literatures included in this study. We argue that this difference is due to the different positions that Italian and Portuguese language literatures enjoy in the Swedish book market, where Italian is the seventh most translated language while Portuguese has a significantly weaker position. As a consequence, Italian literature, which has to stand more on its own feet, shows a larger variety of genres (crime fiction, comics, bestselling novels, reportages, poetry, and classics), which makes the literature visible in more areas of the literary field, whereas Portuguese language literatures are represented by fewer genres (mainly prose and poetry) written by consecrated authors.

However, this result should not be overstated, because even if Italian has a privileged position in Sweden, which, among other things, is certainly related to its ‘past symbolic capital’ (Sapiro, Citation2015, p. 321), another very important result of our analysis is the gap we found between the status of authors in their source cultures and the size of the Swedish publishing houses that published the literature. In both instances, although especially in the Portuguese case, most of the publishing houses were small and micro. The small size of the publishing houses, often run by sole enthusiasts, collides with the position that many of the authors enjoy in their source culture, where they are celebrated as successful and valuable authors. The fact that these authors, in order to be published in Sweden, to a very large extent depended on subsidies and the efforts and enthusiasm of small firms says something about the difficulties even for national literary stars to cross borders. Especially in the case of Portuguese, the lack of ‘horizontal isomorphism’ was striking.

An intriguing result was that the supported titles from the Portuguese and Italian funders did not seem to depend on the existence of previous translations into English. Actually, our results suggest that translations into a globally hegemonic language such as English was of very little importance for these grants, which confirms our hypothesis that institutional funders in the source cultures provide an alternative path for interconnecting semi-peripheral and peripheral cultures. For literature written in Portuguese, and to a certain extent even for the Italian counterpart, the titles published are more likely the results of networking mediators in the ‘interculture’, which overlaps source culture and target culture (Pym, Citation1998, p. 177), aided by support policies. The interconnection between source and target cultures was also observed in the cases of some of the examined funders: the C. M. Lerici Foundation, for instance, is located in the target culture (Sweden) but within a structure belonging to the source culture (the Italian Cultural Institute), which illustrates how source and target cultures are intertwined. Similarly, the The Camões Institute is the most important funder of cultural events regarding Portuguese-speaking cultures in Sweden with one of its centers located at Stockholm University. These findings suggest that the borders between supply-driven and demand-driven support are sometimes blurred, an observation that we argue would need some further scholarly attention.

When it comes to the effects of the support, our results indicate a strong direct connection between supported titles and the authors’ visits to Sweden to promote their books, but despite the financial support and these invitations, the Swedish press did not pay much attention to the authors and their books.

Finally, the supported titles from Italian and Portuguese suffered from a strong male bias. The ratio of male and female writers was so similar in both source languages that it almost seems to be rule that no more than 20% of the subsidies should go to female writers. Obviously, there is no such explicit rule, but perhaps our results reflect a norm that has been observed in previous research. Clearly, this discrepancy needs more attention. We are convinced that the gender imbalance as well as the other issues related to inter-peripheral literary circulation that we have touched upon in this study will receive more scholarly attention in the near future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Cecilia Schwartz

Cecilia Schwartz is Associate Professor of Italian at Stockholm University. Her research focuses on Italian literature, mainly from a transnational and translational perspective. She is currently participating in the research program Cosmopolitan and Vernacular Dynamics in World Literatures. With Laura Di Nicola, she edited Libri in viaggio: Classici italiani in Svezia (2013). Some of her recent publications include the articles ‘Worlding the library’ (2019) and ‘Ferrante Feud: The Italian reception of Elena Ferrante before and after their international success’ (2020) as well as chapters in World Literature: Exploring the Cosmopolitan-Vernacular Exchange, edited by Stefan Helgesson et al. (Stockholm University Press 2018), Sociologies of Poetry Translation: Emerging Perspectives (Bloomsbury 2019), edited by Jacob Blakesley, and Topics and Concepts in Literary Translation (Routledge, 2020), edited by Roberto Valdeón. Her most recent book is La letteratura italiana in Svezia. Autori, editori, lettori (1870-2020), (Carocci Citation2021).

Chatarina Edfeldt

Chatarina Edfeldt is a senior lecturer of Portuguese and a member of the Literature, Identity and Transculturality research group at Dalarna University. She is a member of the research program Cosmopolitan and Vernacular Dynamics in World Literatures (Sweden) and the research groups Intersexualities at ILCML (Institute of Comparative Literature Margarida) at the University of Porto and CEMRI (Study Center of Migration and International Relations) at University Aberta (Lisbon). Her research focuses on Portuguese-speaking literature and culture and world literature from a feminist, gender, and post-colonial perspective. She has published books and articles on the topics of gender issues, literary historiography, and Portuguese-speaking women writers. Her most recent book is a co-edited volume: Narratives Crossing Borders, The Dynamics of Cultural Interaction (Stockholm University Press 2021).

Notes

1 To our knowledge, there are no authors in the former Italian colonies who publish literary texts in Italian. The reasons are manifold: in Libya, for instance, the cultural and literary context was Arabized in 1969 and in the following year the Italians were forced to leave the country. In Somalia there was an Italian Somalian University until the late 80’s, but it mainly published didactic books (how to teach Italian etc.). In Eritrea the dictatorship and the war against Ethiopia drained the country on resources and energies, and the same goes for Ethiopia which had an even smaller Italophone community. Finally, in Albania during the communist era it wasn’t allowed to publish in Italian.

2 The titles in Italian are L’amica geniale (English translation: My Brilliant Friend) and Storia di chi fugge e chi resta (English Translation: Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay).

3 The website of The Swedish Arts Council https://www.kulturradet.se/sok-bidrag/vara-bidrag/litteraturstod/ accessed September 3, 2020.

4 These numbers do not include supported translations from Portuguese of Brazilian literature. This literature has also received support, but it falls outside the scope of the current study.

5 This information is retrieved from an interview by Edfeldt conducted with Assunção Mendonça, an official of DGLAB, at Torre do Tombo in Lisbon, on May 10, 2019. We want to especially thank Assunção Mendonça for valuable assistance and information.

6 ‘Translation database’ URL: http://livro.dglab.gov.pt/sites/DGLB/Portugues/Paginas/PesquisaTraducoes.aspx However, the database listing the translations is not complete, therefore, an additional checking of the published titles was conducted in The Swedish National Bibliographic Database to complete the data URL: http://libris.kb.se/.

7 There are however a number of different private funders in Italy from which foreign publishers might receive support, but then the publisher has to be aware of the funder’s existence. An eloquent example of this is the Swedish translation of Giuseppe Dessì’s novel San Silvano from 1939, which received support from no less than six different Italian funders when it was published in 2011. Significantly, the publisher was Cartaditalia, run by the Italian Cultural Institute in Stockholm.

8 Checking the translated copies turned out to be the easiest way to achieve the results, since there was no information on the supported titles on the Ministry’s website. According to the rules, a publisher must insert a phrase in Swedish and Italian, which acknowledges that the book has been translated thanks to a contribution from the Italian Foreign Ministry.

9 There are 83 Italian Cultural Institutes in the world and their main functions are to promote Italian language and culture abroad, for instance by providing language courses and organizing cultural events such as exhibitions, concerts, inviting writers etc.

10 We would like to express our gratitude to Rachele Giuliani, Università di Bologna.

11 All the granted titles are listed at: https://www.cmlerici.se/.

12 This number includes only first editions, not reprints or re-editions, as the grants are given for the translation costs of the works.

13 This number regards only the first issues of a title, meaning that re-editions are not included (the total amount of editions is 299).

14 The category of micro publishers has been highlighted by Ann Steiner (Citation2019). The micro publishers are: Almaviva, Edition Diadorim, Gondolin, Ariel, Aura Latina, Occident, Lusima Böcker and Panta rei.

15 Astor, Lilla piratförlaget, Urax, Ekerlid, Pontes and Tranan.

16 Considering the statement from the DGLAB - that they grant everyone who applies - these larger publishing houses probably did not solicit funding.

17 Among the middle size publishers were publishing houses such as Brombergs, Carlsson, Leopard and Bazar. The small publishers were Atrium, Contempo, Tranan, Astor, Ades, Artos & Norma, Brutus Östling, Celanders, Elisabeth Grate, Faethon, Fischer& co, Hjalmarson & Högberg, Laurella & Wallin, Nilsson, OEI Editör, while micro publishers were 2 kronors förlag, Hovidius, Nubelicus, Themis, Vesper) Moreover, during the direction of Grossi, the Italian Cultural Institute started publishing a book series of its own, Cartaditalia. According to the information provided by the Cultural Institute and the volumes themselves, they were not necessarily financed by the C.M. Lerici Foundation.

18 The translations database lists the translations into every language of one work sorted by author. URL: http://livro.dglab.gov.pt/sites/DGLB/Portugues/Paginas/PesquisaTraducoes.aspx

19 For this purpose, Robin Healey’s Bibliography of Italian Authors in English Translation (Citation2019) was used. For works published from 2016 and forth the presence of translations were checked in World Cat.

20 These figures do not include anthologies, volumes of selected poems or the Calvino novels which had been translated into Swedish previously.

21 The years through brackets regard the first appearance of the work in Italian and the second refers to the first Swedish translation.

22 For instance, when Umberto Eco’s Swedish publisher since 1983 published Il cimitero di Praga in 2011, it was not due to the fact that the title had been translated into English the year before, but rather a consequence of a long term professional relationship between the Swedish publisher and the Italian author.

23 This information was retrieved from the website of the Italian Cultural Institute’s, where all the cultural events (even in the past) are listed.

24 Other examples are the invitations of Angelo Stano, main illustrator of the comics Dylan Dog and Gianni Pacinotti alias ‘Gipi’ who both participated at the International Festival of Comics in Stockholm, even though not the same year. Another example is Roberto Saviano, who in 2017 visited the Gothenburg Book Fair in order to promote his novel La paranza dei bambini.

25 The information was retrieved by inserting the name of the author, the title and sometimes even the publisher.

References

- Atkin, R. (2020). Does size matter? Questioning methods for the study of ‘small’. In R. Chitnis, J. Stougaard-Nielsen, R. Atkin, & Z. Milutinović (Eds.), Translating the literatures of small European nations (pp. 247–266). Liverpool University Press.

- Broomans, P., & Jiresch, E. (2011). “The invasion of books”. In P. Broomans, & E. Jiresch (Eds.), The Invasion of Books in Peripheral Literary Fields. Transmitting Preferences and Images in Media, Networks and Translation (pp. 9–21). Barkhuis.

- C.M. Lerici Foundation (https://www.cmlerici.se/). Creative Europe Programme of the European Union [n.d] https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/creative-europe_en

- Edfeldt, C. (2020). Recoding Paulina Chiziane’s Vernacular Poetics. Special issue of Interventions, 22(3), 364–38. doi: 10.1080/1369801X.2019.1659167

- van Es, N., & Heilbron, J. (2015). Fiction from the Periphery: How Dutch Writers Enter the Field of English-Language Literature. Cultural Sociology, 9(3), 296–319. doi:10.1177/1749975515576940

- Franssen, T., & Kuipers, G. (2013). Coping with uncertainty, abundance and strife: Decision-making processes of Dutch acquisition editors in the global market for translations. Poetics, 41(1), 48–74. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2012.11.001

- Healey, R. (2019). Italian Literature Since 1900 in English Translation. University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division. Ebook.

- Heilbron, J. (1999). Towards a Sociology of Translation: Book Translations as a Cultural World System. European Journal of Social Theory, 2(4), 429–444. http://doi.org/10.1177/136843199002004002

- Jansen, H. (2019). Imitation, Inertia, and Innovation: The Selection of Italian literature for Translation into Danish. In E. Khachaturyan, & Á. L. Sanz (Eds.), Scandinavia through Sunglasses. Spaces of Cultural Exchange between Southern/Southeastern Europe and Nordic Countries (pp. 41–56). Peter Lang.

- Maia, R., Pinto, M., & Pinto S. (2015). Portugal and Translation Between Centre and Periphery. In Rita Bueno Maia, Marta Pacheco Pinto, & Sara Ramos Pinto (Eds), Translating Portugal Back and Forth: Essays in Honour of João Ferreira Duarte (pp. xvii–xxix). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- The National Library of Sweden (Kungliga biblioteket). (2021). Nationalbibliografin i siffror 2020. Kungliga biblioteket.

- Pym, A. (1998). Method in Translation History. Routledge.

- Sapiro, G. (2015). Translation and Symbolic Capital in the Era of Globalization: French Literature in the United States. Cultural Sociology, 9(3), 320–346. doi:10.1177/1749975515584080

- Sapiro, G., & Heilbron, J. (2018). Politics of Translation: How States Shape Cultural Transfers. In D. Roig-Sanz and R. Meylaerts (Eds.), Literary Translation and Cultural Mediators in ‘Peripheral’ Cultures. Customs Officers or Smugglers? Palgrave Macmillan. 183–208. Ebook.

- Schwartz, C. (2019). “Semi-peripheral relations – The status of Italian poetry in contemporary Sweden”. In J. Blakesley (Ed.), Sociologies of poetry translation. Emerging perspectives (pp. 173–196). Bloomsbury.

- Schwartz, C. (2021). La letteratura italiana in Svezia. Autori, editori, lettori (1870-2020). Carocci.

- The Swedish Arts Council (Kulturrådet) https://www.kulturradet.se/sok-bidrag/vara-bidrag/litteraturstod/

- Steiner, A. (2019). Litteraturen i mediesamhället. Studentlitteratur.

- Vimr, O. (2020). Supply-driven Translation: Compensating for the Lack of Demand. In R. Chitnis, J. Stougaard-Nielsen, R. Atkin, Z. Milutinović (Eds.), Translating the Literatures of Small European Nations (pp. 48–68). Liverpool University Press.