ABSTRACT

China was traditionally a dubbing country, but contemporary viewing habits and the reception of different modes of audiovisual translation have been relatively understudied. This article analyzes how subtitling and dubbing are received among contemporary Chinese viewers, based on the findings of a large-scale online survey distributed to adult participants of different age groups in China. 877 participants responded to the survey from 23 provinces and regions mainly from mainland China. The findings suggest that foreign-language films have a greater appeal to younger audiences, many of whom are inclined to bilingual subtitles. Dubbing tends to be better received among older adults. Interestingly, subtitle fans tend to switch to dubbed versions when accompanied by children and older adults. In addition, positive reviews and public recognition are a stronger impetus to convert subtitle fans and boost the consumption of dubbed films, compared with other factors, such as genre variation and dubbed readaptation. This survey has delved deeper into the translation-related and technical variables that account for the lower popularity of dubbing. Moreover, it highlights a number of areas for future reception research in the Chinese context.

Introduction

China was traditionally a dubbing country, and dubbing reached its heyday in the late 1970s to 1980s when the country began its reform and opening up to the outside world. Dubbed foreign films were widely enjoyed across the country thanks to professional dubbing actors from national dubbing studios, among which the Changchun Film Dubbing Studio in Northeast China and Shanghai Film Dubbing Studio in the southeast were the most prominent. The 1980s saw the mimicking of dubbed lines becoming a popular fad when people were freed from the spiritual shackles of the ‘cultural revolution’ (1966–1976) and began reading previously-banned literature and reciting popular lines from dubbed foreign films. Unfortunately, the 1990s saw a sharp decline in the business of the state-owned film dubbing studios (China Daily, Citation2003). This was mainly driven by the introduction of Hollywood blockbusters (Chen, Citation2011) in tandem with the Chinese audience’s cravings for direct connection with the outside world. More people began to favor the original films with subtitles over dubbing. However, many still enjoy dubbed films, as indicated on online forums (China Daily, Citation2003). Meanwhile, Netflix is ramping up investment in dubbed and redubbed programs internationally, as its recent survey reveals a sudden increase in the consumption of English-language dubbed content and ‘dubbed audio makes audiences more likely to watch an international film or series until the end than when viewed with subtitles’ (Sánchez-Mompeán, Citation2021, p. 181).

The boundary seems blurred as to whether dubbing is still favored by Chinese audiences. If so, who are watching dubbed foreign films in contemporary China and what are the factors that motivate them? As the general hypothesis is that most people prefer subtitles over dubbing, it is also important to investigate the factors that make subtitled foreign films more popular than dubbed versions. In response to these research questions, a large-scale online survey was devised to gather quantitative evidence among Chinese viewers in a bid to delineate a current and comprehensive picture of the viewing tendency of foreign-language films. Admittedly, the study was also motivated by an underlying incredulity as to how a country could transform its national viewing habits from dubbing to subbing in little over two decades. Indeed, there must have been a large extent of complexity and subtlety involved to be unraveled.

Reception studies on audiovisual translation

A vast amount of research on audiovisual translation (AVT) to date has been largely based on descriptivism (Díaz-Cintas & Szarkowska, Citation2020). The situation may vary from one context to another, but given the prevalence of experiential research tradition in the Chinese context (Casas-Tost & Rovira-Esteva, Citation2018; Díaz-Cintas & Szarkowska, Citation2020), the empirical evidence of audience consumption of audiovisual content is sparse, if not absent. The extant literature on AVT is mostly devoted to text-based analysis of subtitles, while dubbing appears largely understudied even within this category (Tang, Citation2014; Xu & Tian, Citation2013). In terms of dubbing, Hu (Citation2020) explores the representation of Soviet allies in the dubbing of Soviet films in 1950s’ China, with a particular focus on the techniques and aesthetics of voicing. A small number of studies have touched upon the domain of audience reception via a combined approach with textual analysis, but with a conspicuous inclination on the analysis of translated subtitles. Tang (Citation2008) examines the subtitled version of Disney’s Mulan accompanied by a small-scale reception study among university students. The results show that those with a higher English proficiency tend to be more concerned with cultural rewriting or modifications, while those students that have to rely on Chinese subtitles display different levels of reception of the subtitles as shaped by a variety of social variables. However, the correlation between audience reception and social variables remains underexplored. In a similar vein, Chen’s (Citation2018) investigation into the effect of subtitled Chinese films on British viewers yields interesting findings in that the data collected from questionnaires show that viewers tend to overestimate their degree of comprehension, especially with respect to cultural-specific items. This hints at the subjectivity of the small-sized self-reported data and thus underlines the necessity of scaling up audience reception research. Indeed, reception research on dubbing in the Chinese context appears to be notably absent. Overall, the ‘descriptive and comparative nature’ (Di Giovanni, Citation2018, p. 160) of current Chinese AVT studies highlights the urgent need for investigating its reception among end users.

This reception study largely fits into the category of ‘repercussion’ in Yves Di Giovanni’s (Citation2018, pp. 56–57) distinction among three types of reception: response, reaction and repercussion. Response deals with the perceptual decoding or legibility of the message, or elucidated as individual viewers’ ability to follow the message (Tuominen, Citation2012, p. 70). Reaction is more related to readability at the psycho-cognitive dimension, such as the inference process involved in understanding the condensed subtitles. Repercussion is understood as preference-related attitudinal issues. Tuominen (Citation2012, p. 70) further argues that reaction is more contextually oriented and repercussion tends to concern the broader social context which impacts the reception of audiovisual content. From a methodological standpoint, response and reaction studies often rely on eye-tracking with new physiological methods being tested, such as electroencephalography (EEG) and electrocardiograms (ECG), to concurrently monitor eye movement, brain and heart activity, to examine the psychophysiological processes involved in the reception of audiovisual content (Díaz-Cintas, Citation2018; Kruger, Citation2019; Kruger et al., Citation2016; Kruger et al., Citation2017; Orrego-Carmona, Citation2016; Romero-Fresco, Citation2020). In comparison, questionnaires and interviews have often been used to investigate repercussion to gain deeper insights into audience behavior and attitudes towards the consumption of audiovisual programs (Ameri & Khoshsaligheh, Citation2020; Briechle & Eppler, Citation2019; Di Giovanni, Citation2016).

While empirical experiments are fruitful and can shed direct light onto professional practices and processes, they are mostly of small-scale and limited scope because of their complex and onerous nature (Díaz-Cintas & Szarkowska, Citation2020). A prominent downside inherent in small-scale experimental reception studies is that the results yielded are highly heterogeneous and hardly replicable because of the diversity of contextual variables and the fluidity of participants’ experience within the small-sized samples. To an extreme extent, the findings could even point to opposite directions. By way of example, Orrego-Carmona (Citation2016) mostly uses eye-tracking data to examine the difference in audience reception between professional and non-professional subtitles among 52 Spanish participants. The results demonstrate that non-professional translations are as good as their professional counterparts and that they do not necessarily have a negative effect on audience reception. Conversely, Ameri and Khoshsaligheh (Citation2020) conduct a netnographic study on the attitudes of a forum-based, Persian-language online community towards dubbing and fan-subbing. Through the thematic analysis and questionnaires of posts and comments, non-professional subtitling is found to raise more negative remarks despite the gratitude poured towards fansubbers for providing free translations. Concerns revolve around literal translations, mistranslations, and unnecessary notes and commentaries in the subtitles. Indeed, some viewers find these to be unacceptable and damaging to the Persian language. Another contributing factor is that the broader social diegetic environment was dubbing-dominated, meaning that the Iranian audience is unaccustomed to subtitling, let alone to the largely-unregulated fan-subbing productions. The heterogeneous results in the reception studies of audiovisual translation thus call for systematic, large-scale studies within a certain cultural or language community to gain a deeper understanding of an overall picture of audience attitudes towards different modes of AVT before smaller projects are pitched in to provide glimpses into specific reception processes. This is largely because individual variation may be less noticeable in a large sample, but can significantly influence the overall picture in small samples (Tuominen, Citation2012). It must be mentioned that a great number of studies have adopted a mixed-methods approach to combining experimental studies and survey or interview data, which has generated both statistically significant and comprehensive qualitative findings (Tuominen, Citation2012). However, given the aforementioned paucity of reception studies in the Chinese context, audience reception of certain modes of AVT remains unclear, especially when the situation is being compounded by the above-described evolving socio-diegetic mediascape. It is thus necessary to conduct a systematic, large-scale survey study to gain an overview of viewers’ attitudes and habits. This study attempts to make an initial inquiry to this end by surveying the general viewing preferences to subtitling and dubbing in order to lay the foundations for future reception studies on AVT in the Chinese context.

Methodology

In line with the objective of establishing public tendency of a specific mode of translation when viewing translated audiovisual films, the survey aims to accommodate a range of factors that may influence viewing habits and elicit as much spontaneous response as possible. Therefore, most items take the form of Likert-type scales, which are highly suitable for measuring attitudes (Likert, Citation1932). The survey consists of individual statements (not questions) to which informants mark their level of agreement or disagreement. The participants were asked to choose among a range of values (1–5) for each option. This method aims to induce more thoughts from the participants and add an extra layer of accuracy and sophistication to the question. The responses were then quantified to latent constructs indicating attitudes, preferences and values (Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2020; Vogt & Johnson, Citation2016). Latent constructs were viewed as underlying factors that may impact audience preferences to subtitling or dubbing. They were mainly drawn from scholarly literature, experiential knowledge and online reviews in discussions of the reception of AVT (as discussed in the next section). In line with a basic form of ontological realism of questionnaire design, this questionnaire was designed along the ontological axis of contextual (general), exploratory (scenario-based) and supplementary questions with incremental complexity and sophistication. This design was supported by the behavioral insights of survey participants, as respondents tend to choose easy answers and skip items when faced with a long list of questions (Dwight & Cederberg, Citation2020). To ensure survey completion and answer quality, the question list was kept short and each question concise. As acknowledged by Díaz-Cintas and Szarkowska (Citation2020, p. 7), reception studies of dubbing or subtitling remain ‘thin on the ground’ due to the complex nature of large-scale empirical experiments. Accordingly, it was thus deemed suitable to design the questionnaire with a rational method guided by face validity, the conceptual framework of which is provided by the implicit hypotheses based on formal or informal observations, empirical evidence, or a review of the literature (Oosterveld et al., Citation2019).

Specifically, the questionnaire consists of 13 questions. This moderate number of items results from the aim to avoid survey fatigue so as to ensure the response rates and quality of completion. As the survey was disseminated among the public, rather than professionals, its length was a prominent consideration in the avoidance of survey fatigue, since such questionnaires have become prevalent since the COVID-19 pandemic (de Koning et al., Citation2021). Nevertheless, most items of the questionnaire contain multiple Likert-scale dimensions aimed at the optimal investigation of each question. The first two questions gather the socio-demographic information of the participants, such as age and place of residence, to gauge the overall representativeness of the survey. Questions 3 and 4 concern general preferences for films and modes of film translation in view of the purpose of this study. In particular, Q3 was designed in the form of a nominal scale question to assign the variables into discrete categories to obtain participants’ general preferences for Chinese or foreign-language films. It serves a gate-keeping role to guarantee that the survey reached out to the intended public. Q4 aligns with the aim of the survey to gain a comprehensive picture of the tendency towards certain modes of AVT. Subsequently, two exploratory questions (Qs5–6) delve deeper into the reasons behind the preferences gleaned in Qs3–4. Qs7–9 purport to use scenario prompts to test participants’ commitment to their selected modes of translation and the circumstances under which they would sway to other choices. Qs10–12 further explore the variables and impact factors of dubbing in response to the initial motivation of the study. The final question is open-ended as a supplementary query to elicit further comments and interest to partake in relevant future studies. Questions apart from the contextual and supplementary questions are key questions, and were thus set as mandatory so as to sustain commitment and avoid skipping. The participants were instructed to rate a value of 1 on variables that were the least suitable to them. Meanwhile, the survey used interpersonal language and juxtaposed task difficulty to maximize respondent interest and motivation.

The survey was constructed in Mandarin due to its intended audience being the Chinese public. It was designed on Wenjuan Xing (Survey Star), the largest survey platform in China, which provides a user-friendly interface and supports multiple question types, including single/multiple selection and various customized scale-question options. It also offers dozens of professional survey templates for reference. Wenjuan Xing also facilitates easy reading of the survey results. The statistics are presented in a range of forms, such as tables, and column or pie charts, so as to facilitate analysis. Important meta-information is also provided to analyze the time, region, and source of each individual survey. The advanced statistical tools embedded in the software, such as statistical categorization, cross-tabulation analysis and self-defined search, are considered useful in cross-examining variables and customizing the search results for specific purposes. Given that the statistics displayed in research findings are mostly systematically distributed, this study adopted mean, over median, value to calculate the central tendency of a particular choice.

The link to the survey was shared on the networking groups of the major social media platforms, Weibo, WeChat and QQ. Probability sampling was used as this enabled every member of the sample frame a known probability of participation (Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2017, p. 11). This method is more suitable for large-scale surveys with a view to ‘ensuring representativeness and maximizing generalization’ (Mellinger & Hanson, Citation2017, p. 12). Meanwhile, to ensure balanced participations, the sample frame (groups) was well stratified in terms of age group distribution. The survey remained open for 2 months from 10 June to 10 August 2022. By the closing date, 877 responses had been received from 23 provinces and regions in China. The following section reports and discusses the findings in detail.

Research findings

The first item was a blank-filling question which asked the participants for their location so as to gain an overall picture of the geographical representativeness of the survey. This question, however, was set as voluntary, considering some participants’ reluctance to disclose this information. It gathered 858 responses out of 877. Given the 19 opt-outs, the number of regions covered by this survey could be slightly higher than 23. In terms of the geographical distribution, approximately 59% of the participants were from the Northern provinces or major cities, such as Tianjin, Beijing, Liaoning and Jilin. The remaining 41% were far more widely distributed across 19 provinces, including such mid-China regions as Henan and Guizhou, eastern and southern provinces, like Zhejiang, Guangdong and Fujian, as well as western parts of China, such as Gansu and Xinjiang. The first question thus laid a solid geographical foundation for balanced findings to emerge.

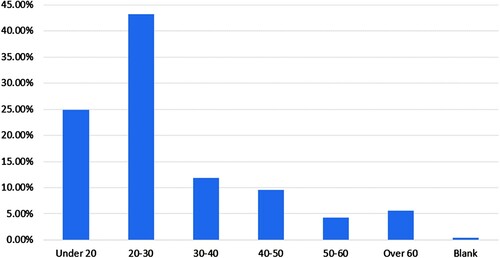

The second question concerned the participants’ ages as an important demographic parameter to correlate with the viewing preference to a specific mode of translation. Likewise, this question was also optional, but only four participants opted out, as shown in . 43.25% of the participants were aged 20–30, with those under the age of 20 forming the second-largest group. In view of the balanced age group distribution in the networking groups, as stated in the previous section, the result of the highest response rate from the 20–30 age group could serve as a credible indicator that translated foreign films are more appealing to the younger public. Meanwhile, this preference declines statistically as the age increases. The high response rates in the first two optional questions partly indicate the openness and positivity that the public holds towards the survey topic.

The third question probed into the participants’ general preference for Chinese or foreign-language films. It allowed for more than one choice under the presumption that many people would watch both types of films. It acts in a gate-keeping role to guarantee that the survey reaches out to the intended public who are in the habit of viewing foreign-language films for their preferred modes of AVT. In terms of the results, 862 responded to the former and 869 to the latter. Hence, a significant number of participants (854) chose both types of films. It should be noted that 15 participants opted for Chinese films solely. However, given that this is only a very small fraction of participants (0.01%), they can be viewed as outliers whose impact could be safely disregarded. The above analysis indicates that the survey was rightly disseminated among the intended groups and the responses gathered are reliable and fit for the purpose of the study.

The question and the results of each choice in Question 4 are translated as follows.

Q4: When you watch foreign-language films, which mode of translation do you prefer?

(Please choose from the 1–5 rating scale in each choice, with 1 being the least suitable and 5 the most suitable.)

A. Original soundtrack and subtitles in the original language.

B. Original soundtrack and Chinese subtitles.

C. Original soundtrack and bilingual subtitlesFootnote1 in Chinese and foreign language.

D. Chinese dubbed and Chinese subtitles.

In the first option, although the highest percentage (26.32%) was recorded for value 1, it would be inappropriate to assume that original soundtrack and language were the least favorite choices because of the comparatively-high rating (25.74%) assigned to value 5. Moreover, value 3 gained only a slightly lower percentage of 24.71%. This suggests that participants tended to be divided in this option and a good number chose to be neutral, as indicated by the high proportion recorded in value 3. With the aid of the self-defined search function, a closer examination of the 25.74% of the responses that went with value 5 suggested that these participants were mostly of younger ages (under 40) and had a higher command of English or other foreign languages based on the additional descriptions supplied by the participants.

Options B and C exhibited a similar pattern of ratings, where value 5 was rated notably higher than others. Especially in option C, 517 participants voted for value 5 in their choice of the original sound and bilingual subtitles – much higher than value 5 in option B, where 370 people chose the original sound and Chinese subtitles. This finding indicates the Chinese public’s inclination to bilingual subtitles when they watch foreign-language films. The next step involved conducting a cross-tabulation analysis to examine the hidden relationship between some variables. This study sought to understand the relationship between age and preference for bilingual subtitles. 87.35% of the participants aged under 20 opted for bilingual subtitles as their favorite (value 5), whereas 85.23% aged above 40 in favor of subtitles chose Chinese subtitles as their favorite. This serves as instructive evidence that films intended for younger audiences may be advised to provide bilingual subtitles. Bilingual subtitles, as a combination of intralingual and interlingual subtitles, is a popular mode of media accessibility in China (Liao et al., Citation2020). In addition to their prevalent use on big screens, they have been gaining momentum among TV broadcasters and online platforms in recent years to attract a wider audience. While scholarship on the impact of bilingual subtitles is relatively limited, initial studies have shown that they do not necessarily result in cognitive overload, as commonly perceived (Liao et al., Citation2020). Rather, they have significant value in enhancing video comprehension and vocabulary learning among English learners (Li, Citation2016). Therefore, the end-users’ responses in the survey accord with previous studies in that bilingual subtitles will remain as a popular mode of translation, especially among younger viewers.

Option D aimed to gather participants’ opinions on dubbed films. As shown above, value 1 received the highest rating (41.76%). This result affirms the findings of prior research and the hypothesis that dubbing has fallen out of favor with contemporary Chinese viewers in view of the inherent fabricated orality and synchronization issues (Yang, Citation2022, p. 161). Further cross analysis reveals that participants aged under 30 mostly assigned low values (1 & 2) and their voting pattern was more radical than older participants. This means that younger participants tended to choose the two end values (1 & 5), whereas some older participants opted for the middle values (3 & 4) in response to this question. Therefore, it would be reasonable to view values above 3 as a sign of favorable inclination to dubbing in these specific cases. After a meticulous investigation into the ‘middle-value’ responses, it was found that 58 participants fell into this category and that their responses could be deemed as quasi value 5, thus elevating the proportion to 25.40% instead of 18.76% as shown in the above graphs. However, it should be noted that this is still a relatively low rating. To follow up, Q10 was designed to specifically examine the reasons for disliking dubbing. In correlation to age, a customized search was followed up for a closer examination of the 25.40% (N = 222) of the surveys. It was found that 66.7% (N = 148) of the participants were over the age of 40, which points to the fact that dubbing tends to be better received among older adults in China.

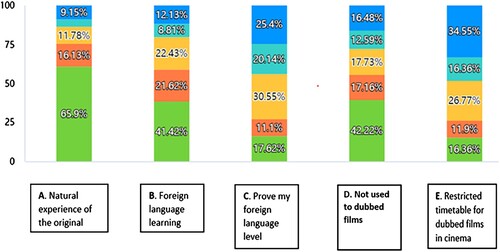

The exploratory Qs 5–6 delved into the reasons for the preferences to subtitling and dubbing elicited in Qs 3–4. Q5 used an interval scale that listed five reasons for choosing films with the original soundtrack and subtitles, as shown in . The variables were informed by reviews on some major social networking forums in China dedicated to media content reviews, such as Douban, Zhihu and Ximalaya. Options C and E emanated from the comments on the online forums where some viewers expressed personal opinions pertaining to the question. For instance, option C was directly informed by some cinema-goers’ comments that they are inclined to choose subtitled foreign films as a form of showcasing their foreign-language mastery (Zhihu, Citation2022). Option E reflects the comments pointing to the fact that the timetables of dubbed films are often very restricted in cinemas, which partly sways them to subtitled films (Ximalaya, Citation2023). Some viewers even bemoaned having to drive to suburbs to watch an animated film dubbed in Chinese with their children. Otherwise, they would have to compromise with the subtitled films (Zhihu, Citation2022). As such, it would be interesting to test out these hypotheses in this survey question.

For options C and E, the highest ratings were concentrated on values 3 (30.55%) and 1 (34.55%), respectively. As there was a notable decrease of ratings in values 4 and 5, this indicates a good level of either emotional or cognitive detachment from the variables. It is noteworthy that two participants went further by commenting on option C in the final open-ended question, stating that it was not about showcasing, but because they were simply not used to dubbed films. However, as value 3 gathered the most votes, it is fair to note that some participants tacitly agreed with this view to some extent. In option E, values 1 and 2 garnered over 50% of the votes, indicating that this claim was relatively ungrounded among the viewers. In other words, the timetabling of dubbed film does not tend to be an important impact factor on the viewing choice.

Among the five options, A and D represent the most preferred reasons for the public inclination to subtitled films, analogous to the majority of reviews on social media or streaming platforms, as demonstrated by the high ratings in value 5, 65.9% and 42.22% respectively. A follow-up question was designed to explore the reasons for option D as to why dubbed films were not favorably received in Question 11. Finally, option B also proved a popular variable in this question given the 41.42% rating in value 5. English learning has been a compulsory subject since primary school in China for several decades. Burgeoning multimedia environments have become an ideal site of entertainment and foreign-language learning for Chinese viewers. With the original audio available, subtitled films have significantly expanded viewers’ exposure to authentic foreign-language materials (Li, Citation2016). Subtitles literally provide learning support through a technological overlay of scripts to facilitate comprehension and vocabulary learning (Robin, Citation2007).

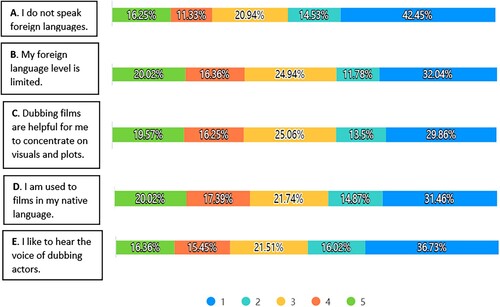

On the other hand, Question 6 attempted to examine why some people preferred to watch dubbed films based on the hypotheses informed by dubbing fans on the forums (Douban, Citation1978). On face value, value 1 attracted the most votes among the five variables. This might be because some participants who preferred subtitles rated value 1 across the five variables in this question, despite its being set as optional. In this case, we could examine the other end of the spectrum, i.e., the ratings for higher values (above value 3). It is thus visually clear that variables B–D attracted more votes, with variable B being the highest. This question informs us about the most probable reasons for dubbing preference. First, dubbed films can better facilitate understanding and channel the attention to visuals and plots, as viewers are freed from scrutinizing bottom-screen subtitles, and can instead focus on ongoing plots and moving pictures. Second, the participants’ limited fluency in the foreign languages may count as a reasonable determinant to direct them to dubbed films. The last main factor concerns the participants’ habitual exposure to dubbed films as they are used to watching audiovisual films in their native language for linguistic immersion and ease of comprehension. It is also linked to the emotional responses to watching dubbed films as exposure to a film in one’s native language may induce a certain level of enjoyment (Khoshsaligheh et al., Citation2018) ().

Qs 7–8 presented two parallel scenarios to test the participants’ commitments to subtitled and dubbed films in terms of whether they would convert to the other translation method under certain circumstances.

Q7: If you are used to watching subtitled foreign-language films with original soundtracks, but for a particular film that you want to watch, there is only a dubbed version available, what would you choose?

Q8: If you are used to watching dubbed films, but for a particular film that you want to watch, only a subtitled version is available (with the original soundtrack in a foreign language), what would you choose?

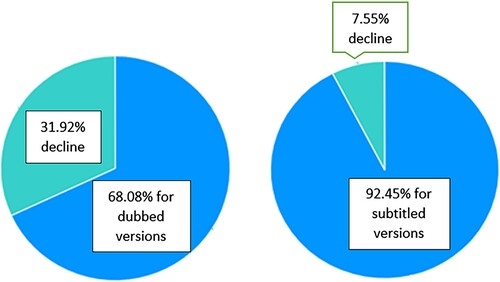

The participants were advised to answer at least one of the two according to their circumstances. 793 and 386 participants responded to Q7 and Q8, respectively. However, these figures may not represent the actual numbers of people who habitually watch subtitled or dubbed films. The results are indicative of a general tendency towards the two modes of AVT under the hypothesized situations, as shown in . The left chart shows that 68.08% of the participants would choose the dubbed version when their preferred subtitled film is unavailable and the remaining 31.92% would decline. In contrast, the right chart demonstrates that 92.45% of the participants would accept the subtitled version even if their preferred dubbed choice is unavailable and only 7.55% would decline.

The participants’ stronger commitment to subtitled films in the above analysis aligns with the anticipated outcome. Therefore, Q9 was designed to delve further into viewers’ reaction to dubbing to determine the circumstances that would sway subtitle fans to dubbing. The circumstances were mostly informed by relevant literature, as presented below, and the recent public sensation towards dubbing by the reproduction of classic English films (Douban, Citation2022).

Q9: Even if you are used to subtitled foreign-language films in the original soundtrack, would you choose dubbed films under the following circumstances?

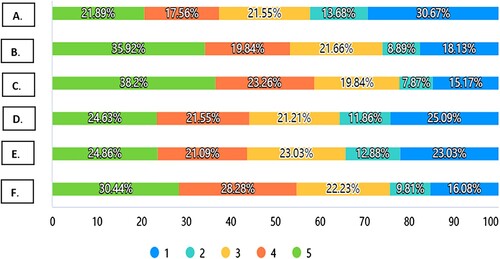

As shown in , interestingly, options B, C and F notably received the highest ratings in value 5, compared with other horizontal values in the same options. Especially in B and C, when queried about whether they would switch to dubbed films when watching with children and older people, 35.92% and 38.2% of the participants, respectively, rated value 5. This demonstrates their awareness of the values of dubbing for these aged-related groups as dubbing tends to be considered more suitable for younger children and older adults in view of their relatively lower capacities of reading and comprehension (d’Depp et al., Citation2010; d’Ydewalle & De Bruycker, Citation2007). This view may be open to discussion in some traditionally subtitling countries where subtitles are preferred among young children. Likewise, older people may not necessarily be outperformed by young adults, possibly due to the long exposure to subtitles across the nation (Perego et al., Citation2015). However, dubbing reception in China still fits in the mainstream circumstances, as the analysis in Q4 shows that dubbed films in China are mainly consumed by older adults, although the case for children requires substantiation by further empirical research. Option F attracted consistently high ratings to higher values (4 and 5), 28.28% and 30.44%, respectively. This shows that positive reviews and public recognition are strong impact factors which can potentially boost the consumption of dubbed films. Option E also gathered the highest rating horizontally in value 5 (24.86%), but was counterbalanced by a similar percentage in value 1 (23.03%). This implies a somewhat divided opinion towards the phenomenon of dubbed readaptations and would serve as an interesting line of inquiry on the reception of these films. Option A seems the least favorable variable given the highest rating on value 1 (30.67%), making it the weakest impact factor among the five options. This indicates that genre variation is unlikely to sway subtitle fans to dubbing, even for animated films that are mostly prone to dubbing production because of their large proportion of child viewers (Mompeán, Citation2015).

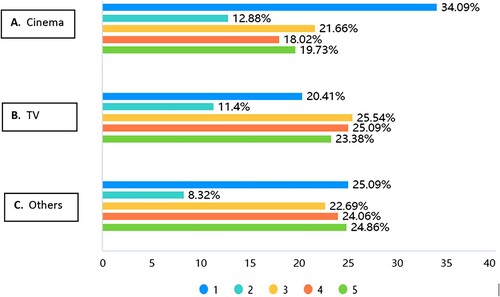

Q10 sought to further explore the contextual factors that impact viewers’ choice of dubbing. It asked about the sites the participants chose to watch dubbed films. As shown in , a range of percentages were assigned to values 1–5 in each option, meaning that a trimmed mean method was used to calculate a statistical value of central tendency. It involved the calculation of the mean after disregarding the values at the high and low end. The trimmed mean values for cinema, television, and streaming platforms were calculated as 19.80%, 22.96% and 23.87%, respectively. Online platforms were thus considered the preferred sites on which to watch dubbed films.

Moreover, the participants were invited to specify details in each option, which became useful for shedding light on the reasons behind their choices. The main reasons are listed from each choice as follows. The positive stimuli for cinema were better sound quality, filmic experience and atmosphere. A small number of participants voiced their concerns relating to dubbed films. Indeed, they believed dubbed voices did not play out well in cinemas’ surround sound systems, meaning that it would not be worth the money to watch dubbed films in cinema. As for television, flexibility and convenience drew the participants to this choice, and CCTV Channel-6 (the official film channel of China Central Television) was unanimously mentioned as the venue to watch dubbed films. Lastly, the online option received more responses given its popularity among the participants who listed cost-saving and flexibility as the main reasons. The main streaming websites nominated were Youku, Bilibili, Tencent, Mango TV and Aiqiyi, or the mobile apps of these services.

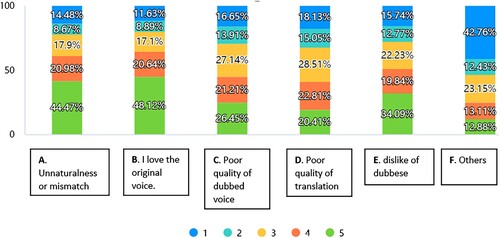

As previously mentioned, Q11 was designed to explore the reasons for the dislike of dubbed films. As shown in , six options were presented and participants were also invited to provide further information they deemed relevant. The ratings of value 5 were notably high in options B, A and E, which stood out as the main reasons. This largely confirms the common speculation that dubbed films tend to contradict public cravings for originality and incur discomfort regarding unnatural and fabricated voices. The open-ended nature of this question offered the participants’ space to voice their opinions. The responses were categorized in line with the three options. In terms of unnaturalness, some recipients reported generally unnatural or strange feelings, while others gave more specific answers in terms of strange intonation and phrasing. One recipient gave an especially descriptive account of watching an animated film in dubbing. The Taiwanese accent of the dubbed voice nearly ruined the entire experience, which made them feel uncomfortable and displaced. In addition, the adaptations into the local colloquialism were also described as cringeworthy. For option B, the inclination to original soundtrack, some participants made it clear that the original voice matched the characters perfectly. Moreover, the jokes and innuendos created by puns or word play could be best appreciated in the original soundtrack because these elements would mostly be toned down or become lost in dubbed voices. Option E concerned the attitude towards ‘dubbese’, known as the patterned reading of foreign scripts stemming from the Golden Era of dubbing, namely the 1970s and 1980s. Many dubbed films during this period were tinted with a style of mixed exquisiteness and exaggeration in both phrasing and timbre (Xu, Citation2017). Many viewers can still feel the ‘dubbese’ style in contemporary dubbed films, which explains why value 5 gained the most votes in this option. Some participants commented further that ‘dubbese’ was not inductive to thorough expression of emotions. Others appreciated that ‘dubbese’ was reminiscent of the good old days of dubbing, but may be unsuitable for current times.

Option D addressed the desirable quality of translation in dubbing. Although the mean value was not the highest, the open-ended responses shed much light on this issue. Some participants mentioned the errors or distortions in dubbed films. A small number insightfully pointed out some distortions due to lip synchronization. Others sensed that the translated language was unable to match the filmic era and that some of the dialogue sounded like the product of machine translation. In terms of the dubbing effect in option C, responses were concentrated on the unsatisfactory quality of lip synchronization and isochrony. Lip synchronization is related to mouth articulation, known as phonetic synchrony. This is where most criticism was directed regarding the poor lip-sync quality that disrupted their viewing experience. On the other hand, some participants expressed concerns over a certain degree of semantic distortion that twisted the plot for the pure sake of lip-syncing. Isochrony refers to the equal duration of utterances between original and translated dialogues (Chaume, Citation2012, p. 72). Some participants described the latency between source and target dialogues as disturbing and uncomfortable. Interestingly, a few participants also mentioned the mismatch between pictures and dubbed voices. This echoes Whitman-Linsen’s (Citation1992) typology of character synchrony that refers to the coincidence of dubbed voices and audience expectations of what the on-screen actors’ voices should sound like in a specific diegetic environment. As Chaume (Citation2012, p. 70) further points out, this issue is more directly related to dubbing actors’ dramatizations, rather than a type of synchronization that directly affects the decision-making process of the translator and dialogue writer. Nevertheless, this is a relevant parameter that affects viewers’ experience of a dubbed film and would be worthy of future psychological evidence for a robust investigation. The last option of ‘others’ also attracted a fair amount of feedback, although the majority has been addressed in the above analysis. The comments largely focused on the homogenizing effect of dubbed voices that confined speech variation and emotional expression in the original. Some also criticized the distortions and awkward adaptations in translation.

Q12 aimed to examine the emotional impact that classic dubbed films may have on the viewers. It was also considered instrumental to ascertain the current level of inclination to dubbing among the contemporary viewers. The participants were asked to choose their favorite films via multiple choices in order to give full play to their emotional attachment. They were also given the choice to nominate others as appropriate. The dubbed films listed in were selected from a classic repertoire covering a variety of world regions (Ifeng, Citation2013; Sina, Citation2022), which has been commonly rated as the films that were ‘lodged in personal memories and nostalgia for a bygone past’ among vast numbers of the public, and continue to ‘insinuate itself in the form of commercial culture, star culture, and the cyber sphere to give popular appeal’ (Xu, Citation2017, p. 58). The parenthetical information encompasses the original language and the year of production of the dubbed version. The findings show that 28.96% of the participants voted for none and the age groups were almost exclusively under 30. This indicates that some young viewers born after China’s golden era of dubbed films (after 1990s) are explicitly not keen on dubbed films. Among the first five options, European dubbed films tended to garner more fans, although films from Japan representative of other countries were also relatively well-received, as shown in option E.

Table 1. Ratings for favorite dubbed films Question 11.

Approximately 80 people expanded their responses to option F and shared their favorites. Some older participants listed Russian films, such as Lenin in October and Lenin 1918, likely due to the flourishing of ‘Sovexportfilms’ (Chen, Citation2004) in China resulting from an economically – and politically-motivated cultural policy in the 1950s–60s. When dubbing was the official and pre-eminent translation method, the extensive public exposure of Soviet films produced many resounding lines that continue to ring in the ears of older generations. A small number of younger participants indicated that some Korean dramas, such as High Kick, were extremely well-dubbed, to the extent that they surpassed the original. The Korean drama series was dubbed by Jingcheng Zhisheng, a private studio that mainly specializes in intralingual films and dramas. Given the scope of the article, it would be of future interest to look into this rare dubbing success in contemporary times.

At the end of the survey, the open-ended Q13 was designed to elicit more elaborate answers on dubbed films from the participants and collect responses from the end users’ perspective. 198 people responded to this question and the results were visualized via the semantic cloud method generated in the software.

As the survey was conducted in Mandarin, so was the semantic cloud. Therefore, the findings were analyzed and are presented below in English in their order of frequency. The comments are grouped into more integrated categories, as shown in .

Table 2. Findings for Question 13.

The responses for Q13 were more varied and the overall response rate was satisfactory (198 out of 877). This largely ensured the representativeness of the findings. As shown in , the majority of the participants pointed out the deficiencies of dubbing for various reasons, which can shed some light on contemporary dubbing practices. The category of ‘others’ included some vague answers, as some participants responded with such simple answers as ‘very good’ or ‘it’s okay’. It was unclear whether these responses related to dubbing or to the survey in general. Given the small number, the responses may well count as outliers and be safely disregarded. It is worth mentioning that the participants were also invited to share their contact details for potential follow-up research. 99 willingly shared their emails and phone numbers along with some favorable notes to indicate their interest in further participation.

Summary and conclusion

The findings suggest that, in contemporary China, foreign-language films are more appealing to younger audiences, many of whom are inclined to bilingual subtitles, while dubbing tends to be better received among older adults. Subtitle fans generally showed a stronger commitment to subtitled films, but many would still switch to dubbed versions when accompanying children and older adults. In addition, positive reviews and public recognition were found to be strong stimuli for converting more subtitle fans and boosting the consumption of dubbed films, in comparison to such other factors as genre variation and dubbed readaptations.

This survey has delved deeper into the variables that account for the lower popularity of dubbing, especially among young viewers. The foremost reason cited was the unnatural nature of the intonation, regional accents and local adaptations. Translation issues associated with errors, distortions and loss of humor were also listed as major concerns of the quality of dubbing. Dubbing practitioners should be alarmed that some younger viewers are against the practice of having to bend meaning for the sake of lip-syncing. The new generation of viewership may more strongly demand truth and transparency in any form of AVT to which they are exposed in today’s digital mediascape. Finally, critiques of dubbed voices mainly revolve around the influence of ‘dubbese’ that homogenizes characterization and restricts emotive expression in contemporary dubbed films. Moreover, various issues related to synchronization are also a locus of concern among viewers.

In view of the above discussions, it can be concluded that China has transformed into a subtitling country since it passed its golden era of dubbing in the 1980s. Despite the complexities and nuances involved in the viewerscape, the transformation can largely be ascribed to the following four factors. Practically, younger generations are highly accustomed to original audiovisual products as bilingual materials have been widely used in foreign-language learning in China since English was integrated into the national curriculum in the late 1980s as part of a national reform scheme. Spiritually, the enthusiastic engagement with subtitled foreign-language films could be seen as an implicit act of breaking from the orthodox ideology and seeking spiritual independence, which has largely been brought about by the implementation of the economic reform in the 1980s. Culturally speaking, it would be far more taxing for two distant cultures and languages, such as Chinese and English, to merge, compared with intra-European combinations. ‘Exchanging faces and matching voice’ (Du, Citation2018) as the ideal pursuit of dubbing is hard, if not impossible, to achieve and resonate with contemporary Chinese audiences. Economically, this is the globalized era for fast turnout and high profit in stark contrast to the context in which dubbed films emerged. The vast majority of dubbed films were secretly produced during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s–1970s as ‘internal reference films’. Unrivalled time and energy were devoted to the productions from the older generation of dubbing actors, which yielded great success, especially in comparison to the declining quality and popularity of contemporary dubbed works. This being said, there is ample space to revive the reception of dubbed films in view of cherished nostalgia from the participants and the potential areas for ‘converting’ fans of subtitling, as outlined in the above analysis.

Future directions

Moving forward, the survey has identified a number of areas for future inquiry. As the study was aimed at adult groups, the consumption of dubbed films among children may need to be pursued with renewed empirical data. This article opens up varied and interesting discussions on the emotional or psychological responses to dubbed and subtitled films based on some open-ended constructs, which would be worthy of future research. The survey touched upon a case of dubbing success in Korean drama translation, which would offer valuable insights for current dubbing practices in China. The survey has built up a useful mailing list for follow-up studies, especially when some of the participants indicated that they were themselves dubbing actors in national and private studios. This could open up new avenues of empirical research for exploring the dubbing process and industry standards in contemporary China. Finally, it has been a joy and privilege to be able to conduct a study of the public and for the public, albeit in a small way.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank all of the participants of this survey for their selfless contributions, and the reviewers and editors for their valuable advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jingjing Li

Jingjing Li is Lecturer of Translation and Interpreting Studies at the University of Leicester. She lectures a variety of translation-related modules including Audiovisual Translation and Interpreting. Her main research interests rest on political discourse translation and multimodal translation studies. Her series of research outcomes have been published in the leading peer-reviewed, SSCI-indexed journals in translation studies. She has recently completed ‘The Construction and Application of the Bilingual Terminology Knowledge Database of Chinese Political Discourse’ granted by the National Social Science Foundation of China [17BYY189] as the principal investigator.

Notes

1 Bilingual subtitles refer to the subtitles in the source and target languages displayed at the same time.

References

- Ameri, S., & Khoshsaligheh, M. (2020). An experiment on amateur and professional subtitling reception in Iran. SKASE Journal of Translation and Interpretation, 14(2), 2–21.

- Briechle, L., & Eppler, E. D. (2019). Swearword strength in subtitled and dubbed films: A reception study. Intercultural Pragmatics, 16(4), 389–420. https://doi.org/10.1515/ip-2019-0021

- Casas-Tost, H., & Rovira-Esteva, S. (2018). A quest for effective and inclusive design of Chinese characters in subtitling. International Journal of Asian Language Processing, 28(1), 31–47.

- Chaume, F. (2012). Audiovisual translation: Dubbing. St Jerome Publishing.

- Chen, L. (2018). Subtitling culture: The reception of subtitles of fifth generation Chinese films by British viewers [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Roehampton]. Semantic Scholar. https://pure.roehampton.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/1004871/Subtitling_culture_the_reception_of_subtitles_of_fifth_generation_Chinese_films_by_British_viewers.pdf

- Chen, T. M. (2004). Internationalism and cultural experience: Soviet films and popular Chinese understandings of the future in the 1950s. Cultural Critique, 58(1), 82–114. https://doi.org/10.1353/cul.2004.0021

- Chen, X. (2011). A dubbing decline. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/671353.shtml

- China Daily (2003). Golden dubbing age falls on deaf ears. http://www.china.org.cn/english/2003/Dec/82870.htm

- de Koning, R., Egiz, A., Kotecha, J., Ciuculete, A. C., Ooi, S. Z. Y., Bankole, N. D. A., Erhabor, J., Higginbotham, G., Khan, M., Dalle, D. U., Sichimba, D., Bandyopadhyay, S., & Kanmounye, U. S. (2021). Survey fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis of neurosurgery survey response rates. Frontiers in Surgery, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2021.690680

- Depp, C. A., Schkade, D. A., Thompson, W. K., & Dilip, V. J. (2010). Age, affective experience, and television use. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 39(2), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.020

- Díaz-Cintas, J. (2018). Audiovisual translation in mercurial mediascapes. In M. Ji, & M. Oakes (Eds.), Advances in empirical translation studies (pp. 1–16). Cambridge University Press.

- Díaz-Cintas, J., & Szarkowska, A. (2020). Introduction: Experimental research in audiovisual translation: Cognition, reception, production. Special Issue of The Journal of Specialised Translation, (33), 3–16.

- Douban. (1978). Review of Death on the Nile (1978). https://movie.douban.com/subject/1302100/

- Douban. (2022). 10 facts you need to know about the readapted Death on the Nile. https://m.douban.com/movie/review/14227388/

- Du, W. (2018). Exchanging faces, matching voices: Dubbing foreign films in China. Journal of Chinese Cinemas, 12(3), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508061.2018.1522802

- Dwight, E., & Cederberg, G. (2020). Five ways behavioural insights can improve survey design. Pew Research Centre. https://behaviouraleconomics.pmc.gov.au/blog/five-ways-behavioural-insights-can-improve-survey-design

- Di Giovanni, E. (2016). Reception studies in audiovisual translation research: The case of subtitling at film festivals. Trans-kom, 9(1), 58–78.

- Di Giovanni, E. (2018). Dubbing, perception and reception. In E. Di Giovanni & Y. Gambier (Eds.), Reception studies and audiovisual translation (pp. 159–177). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Hu, N. (2020). Familiar strangers: Images and voices of Soviet Allies in dubbed films in 1950s China. China Perspectives, 1(2020), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.4000/chinaperspectives.9907

- Ifeng (2013). The future of dubbed films in the historical glory. http://culture.ifeng.com/gundong/detail_2013_06/21/26654280_0.shtml

- Khoshsaligheh, M., Pishghadam, R., Rahmani, S., & Ameri, S. (2018). Relevance of emotioncy in dubbing preference: A quantitative inquiry. The International Journal of Translation and Interpreting Research, 10(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.110201.2018.a05

- Kruger, J. L. (2019). Eye tracking in audiovisual translation research. In L. Pérez-González (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of audiovisual translation (pp. 350–366). Routledge.

- Kruger, J. L., Doherty, S., & Ibrahim, R. (2017). Electroencephalographic beta coherence as an objective measure of psychological immersion in film. International Journal of Translation, 19, 99–111.

- Kruger, J. L., Soto-Sanfiel, M. T., Doherty, S., & Ibrahim, R. (2016). Towards a cognitive audiovisual translatology: Subtitles and embodied cognition. In R. M. Martín (Ed.), Reembedding translation process research (pp. 171–194). John Benjamins Publishing.

- Li, M. (2016). An investigation into the differential effects of subtitles (First Language, Second Language, and Bilingual) on second language vocabulary acquisition [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of Edinburgh. Edinburgh Research Archive. https://era.ed.ac.uk/handle/1842/22013

- Liao, S., Kruger, J. L., & Doherty, S. (2020). The impact of monolingual and bilingual subtitles on visual attention, cognitive load, and comprehension. The Journal of Specialised Translation, (33), 70–98.

- Likert, R. A. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22(140), 1–55.

- Mellinger, C. D., & Hanson, T. A. (2017). Quantitative research methods in translation and interpreting studies. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mellinger, C. D., & Hanson, T. A. (2020). Methodological considerations for survey research: Validity, reliability, and quantitative analysis. Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series: Themes in Translation Studies, 19, 172–190.

- Mompeán, S. S. (2015). Dubbing animation into Spanish: Behind the voices of animated characters. The Journal of Specialised Translation, (23), 270–291.

- Oosterveld, P., Vorst, H. C. M., & Smits, N. (2019). Methods for questionnaire design: A taxonomy linking procedures to test goals. Quality of Life Research, 28(9), 2501–2512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02209-6

- Orrego-Carmona, D. (2016). A reception study on non-professional subtitling: Do audiences notice any difference?. Across Languages and Cultures, 17(2), 163–181. https://doi.org/10.1556/084.2016.17.2.2

- Perego, E., Missier, F. D., & Bottiroli, S. (2015). Dubbing versus subtitling in young and older adults: Cognitive and evaluative aspects. Perspectives, 23(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2014.912343

- Robin, R. (2007). Commentary: Learner-based listening and technological authenticity. Language Learning and Technology, 11(1), 109–115.

- Romero-Fresco, P. (2020). The dubbing effect: An eye-tracking study on how viewers make dubbing work. The Journal of Specialised Translation, (33), 3–16.

- Sánchez-Mompeán, S. (2021). Netflix likes it dubbed: Taking on the challenge of dubbing into English. Language & Communication, 80, 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2021.07.001

- Sina.com (2022). Twenty classic dubbed films in the 1980s. http://k.sina.com.cn/article_7539316313_1c160d659001014rs7.html

- Tang, J. (2008). A cross-cultural perspective on production and reception of Disney's Mulan through its Chinese subtitles. European Journal of English Studies, 12(2), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825570802151413

- Tang, J. (2014). Translating Kung Fu Panda's Kung Fu-related elements: cultural representation in dubbing and subtitling. Perspectives, 22(23), 437–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2013.864686

- Tuominen, T. (2012). The art of accidental reading and incidental listening: An empirical study of the viewing of subtitled films [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Tampere, Trepo. https://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-44-9008-8

- Vogt, W. P., & Johnson, R. B. (2016). The Sage dictionary of statistics and methodology (5th ed.). Sage Publishing.

- Whitman-Linsen, C. (1992). Through the dubbing glass. Peter Lang.

- Ximalaya (2023). vol. 349 Dialogues with producers on box office and film production (trans). https://www.ximalaya.com/audio/397580068

- Xu, M., & Tian, C. (2013). Cultural deformations and reformulations: A case study of Disney's Mulan in English and Chinese. Critical Arts, 27(2), 182–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/02560046.2013.783956

- Xu, P. (2017). Interpretative dubbing: The voice stars in the 1980s China [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Washington. ResearchWorks Archive. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/bitstream/handle/1773/39879/Xu_washington_0250O_17069.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=n

- Yang, F. (2022). Orality in dubbing vs. subtitling: A corpus-based comparative study on the use of mandarin sentence final particles in AVT. Perspectives, 30(1), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2021.1974900

- d’Ydewalle, G., & De Bruycker, W. (2007). Eye movements of children and adults while Reading television subtitles. European Psychologist, 12(3), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040.12.3.196

- Zhihu (2022). Reviews of Massacre on River Nile. https://www.zhihu.com/search?type=content&q=%E5%B0%BC%E7%BD%97%E6%B2%B3%E6%83%A8%E6%A1%88%20%E9%85%8D%E9%9F%B3%E7%89%88%E5%A4%96%E8%AF%AD%E6%B0%B4%E5%B9%B3