ABSTRACT

This study assessed prognostic factors and the role of vitrectomy in patients with subretinal abscesses secondary to K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis. We reviewed published studies, including three cases from our cohort. Among 50 eyes, 26 had poor visual outcomes (final visual acuity <20/800, eyeball removal, or phthisis bulbi). Poor outcomes correlated with delayed ocular symptom-to-diagnosis time, initial visual acuity <20/800, severe vitritis, and macular involvement of abscesses (p < 0.001, p = 0.008, p < 0.001, and p = 0.033, respectively). Vitrectomy had a trend towards reducing eyeball removal and phthisis bulbi rates compared with non-vitrectomy (10.8% vs 30.8%, p = 0.181). However, the final visual acuity was not different and the rate of retinal detachment tended to be higher in vitrectomized eyes (45.9% vs 15.4%, p = 0.095). The study suggested that vitrectomy and drainage of K. pneumoniae subretinal abscesses could be avoided in patients with a mild degree of vitritis.

Endogenous endophthalmitis accounts for 2–8% of all types of endophthalmitis.Citation1,Citation2 It is caused by hematologic spreading of infective foci from the primary lesion. A subretinal abscess is a less common presentation of endogenous endophthalmitis and is associated with a worse visual prognosis.Citation3 K. pneumoniae is gram-negative bacilli which commonly causes endogenous endophthalmitis, especially in East Asian countries. Liver abscess is the predominant primary infection, although it can arise from pyelonephritis and pneumonia.Citation4,Citation5 Previous reports on K. pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis presenting with a subretinal abscess showed mixed results in visual outcomes with various treatment strategies.Citation6–10 Because of the rarity and varying severity of the disease, there has been no definite treatment guideline for this condition. This study aimed to investigate clinical characteristics, therapeutic approaches, and treatment outcomes of endogenous K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess.

Materials/subjects and methods

This study was approved by the Siriraj Institutional Review Board, Mahidol University (COA No. Si 561/2022). The electronic medical records of three patients who were diagnosed with K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscesses with different severity were reviewed. Pertinent clinical data were collected.

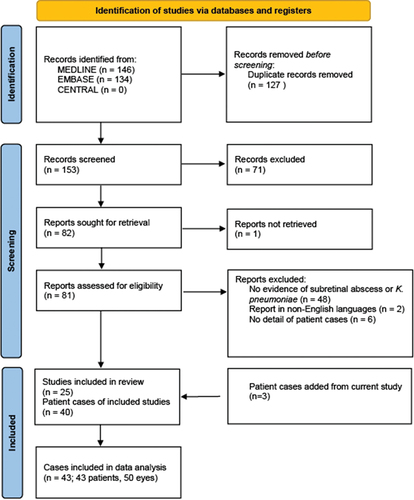

A review of previous publications on K. pneumoniae with subretinal abscess was also performed. We searched in MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL databases by using the search terms subretinal abscess, Klebsiella endophthalmitis, and invasive Klebsiella syndrome. All reports of patients with a diagnosis of endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess based on clinical presentation with laboratory evidence for K. pneumoniae were included. Patients whose microbiological investigations were negative, articles with duplicated cases, and articles published in non-English languages were excluded from data analyses. We performed the last search in October 2022. The methodological quality of previously published studies was evaluated by the tool proposed by Murad and colleagues.Citation11 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guideline was used for reporting the results of the review.

If available, demographic data including sex, age, systemic illnesses, and previous ocular diseases were collected. The clinical information, laboratory results, medical and surgical treatments, as well as the final visual acuity and complications were also obtained. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics version 29 (SPSS, Inc.). Data were presented as number (%), mean ± standard deviation or median (P25, P75) as appropriate. For comparison between two groups, Pearson Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables, whereas Mann-Whitney U test was used for quantitative variables. In all analyses, p-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Case 1

A healthy 36-year-old man presented with fever and jaundice. Laboratory tests were positive for leukocytosis, neutrophils predominance, direct hyperbilirubinemia, and elevation of liver enzymes. Fasting plasma glucose was normal. Serology for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, and HIV was negative. He was diagnosed with a liver abscess confirmed by an abdominal CT scan. Empirical intravenous metronidazole and ceftazidime were given. The patient underwent percutaneous drainage of the abscess. The pus from the drainage site showed gram-negative bacilli. Three days later, he complained of floaters and blurred vision in the left eye. The diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis was suspected and the patient was referred to our hospital.

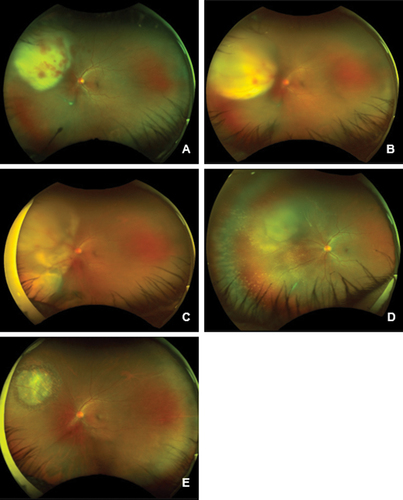

On examination, the best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) on the left eye was 6/48. The intraocular pressure (IOP) was 4 mmHg. Slit-lamp examination revealed injected conjunctiva and chemosis, 1+ cells in the anterior chamber without hypopyon and plasmoid aqueous, clear lens, and trace anterior vitreous cells. Funduscopic examination of the left eye showed 0.5+ vitreous haze and large yellow-white subretinal lesion with overlying intraretinal hemorrhages at the superonasal region (). A diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis with a subretinal abscess was made. Vitreous tapping and intravitreal injection of ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 ml) were done. Topical antibiotics and cycloplegics were prescribed. The vitreous specimen culture and PCR results did not reveal any organisms. However, both blood culture and liver abscess culture were positive for K. pneumoniae. Intravenous ceftazidime was continued and later switched to oral ciprofloxacin after 18 days. The patient received a total of 3 injections of intravitreal ceftazidime, 3 days apart for each injection. The subretinal abscess was progressively shrunken, and the inflammation was improved over time after the intravitreal injections. There was a transient increase of subretinal fluid around the abscess in the first week of treatment. A careful examination did not identify any retinal breaks. A week after the 3rd intravitreal injection, the subretinal fluid spontaneously resolved along with improvement of the subretinal abscess ().

Figure 1. Ultrawidefield fundus photograph of the right eye of case 1. (a) A subretinal abscess with overlying intraretinal hemorrhages at the superonasal region at the initial presentation. (b) Three days after the 1st intravitreal injection, the yellowish pus content in the abscess appeared smaller but subretinal fluid seemed to increase. (c) Three days after the 2nd intravitreal injection, the pus content appeared less cloudy but the subretinal fluid markedly increased. There were no retinal breaks. (d) One week after the 3rd intravitreal injection, the subretinal fluid spontaneously resolved with remaining subretinal yellowish precipitate. Topical steroid was challenged on this day. E. Four months later, the area of the previous subretinal abscess turned into a chorioretinal atrophic scar and laser retinopexy was performed around the scar. VA was 6/6 and the retina was attached.

At the 8-month follow-up visit, the area over subretinal abscess turned into chorioretinal atrophic scar. Therefore, laser retinopexy around the atrophic area was done for prophylaxis of retinal breaks. The final BCVA was 6/6 and the retina remained attached.

Case 2

A 64-year-old man presented with blurred vision on the right eye for 1 day. He had a history of fever with chill and malaise for 5 days. His comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidemia, and mitral valve regurgitation. Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis with neutrophil predominance and elevated alkaline phosphatase. There was no history of ocular surgery and trauma. BCVA of the right eye was counting fingers at 1 foot and the IOP was 12 mmHg. Anterior segment examination showed medium-sized whitish keratic precipitates, grade 4+ anterior chamber cells, and 0.6 mm of hypopyon. Funduscopic examination showed grade 3 vitreous haze and 4-disc diameter in size of elevated yellowish retinal lesion at peripheral temporal retina. The ocular ultrasonography of the right eye demonstrated a dome-shaped lesion at the temporal region with heterogeneous hyperechoic internal content.

The diagnosis of endogenous endophthalmitis with a subretinal abscess was made. Vitreous tapping and intravitreal injection of vancomycin (1 mg/0.1 ml) and ceftazidime (2.25 mg/0.1 ml) were then performed. Topical fortified vancomycin, ceftazidime, and cycloplegics were prescribed. Intravenous vancomycin and ceftazidime were also given. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a 2 × 3 cm liver abscess. Blood culture later revealed gram-negative bacilli and the intravenous and topical vancomycin were subsequently discontinued.

Two days after intravitreal injection, the BCVA decreased from counting finger to hand motion and there was no improvement in the inflammation. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV), repeated vitreous sampling and intravitreal ceftazidime injection were then performed. Intraoperative findings showed grade 3 vitritis, dense vitreous clumps at the inferotemporal vascular arcade, and a subretinal abscess at the temporal region. (Supplementary material 4) Only core vitrectomy was performed in this operation. The vitreous culture and molecular identification did not identify any organisms but the blood culture grew K. pneumoniae. The inflammation was improved after the vitrectomy; however, a follow-up ultrasonography 10 days later revealed an inferior retinal detachment. A second operation was then performed to repair the retinal detachment. Intraoperatively, a retinal break was seen on necrotic retinal tissue overlying the resolving abscess temporally and another patch of subretinal infiltration at the inferonasal retina was found. Endolaser photocoagulation was performed around the retinal break, the necrotic area, and the area of subretinal infiltration. The retina was reattached under silicone oil endotamponade. No intravitreal antibiotics were given at the end of this surgery. Intravenous antibiotics were given for 14 days and later switched to oral levofloxacin for 28 days. Six months later, the patient underwent cataract surgery with silicone oil removal. At the last follow-up visit, BCVA was 6/24 and the retina remained attached. There was postoperative macular edema, which was improved by topical 1% Nepafenac applied 4 times daily and intravitreal triamcinolone (4 mg/0.1 mL) (Supplementary material 5).

Case 3

A 41-year-old male with a history of heavy alcohol drinking presented with epigastrium pain and lower gastrointestinal bleeding. He was febrile and had distension and generalized guarding on abdominal palpation without signs of liver failure. Laboratory tests revealed increased band form of leukocyte, serum creatinine rising, elevated serum aminotransferase, and direct hyperbilirubinemia. Moreover, HbA1c level was measured at 7.9%, leading to a newly diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. CT abdomen revealed a ruptured liver abscess and rectal abscess with intraabdominal pus. (supplementary material 6) Intravenous ceftriaxone was started, and he was admitted to the general surgery unit. Percutaneous drainage of a liver abscess and intraabdominal collection were performed. The pus and blood culture grew K. pneumoniae. After the operation, the patient had an alteration of consciousness due to sepsis and delirium tremens. He was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit.

Five days after the admission, the patient had conjunctival injection and chemosis of the left eye. The bedside ophthalmic examination revealed proptosis, corneal edema, plasmoid aqueous, and grade 4 vitreous haze in the left eye. The diagnosis of K. pneumoniae endogenous panophthalmitis was made. Bedside subconjunctival and intravitreal injections of ceftazidime were given. On the next day, he underwent vitrectomy with vitreous sampling. Preoperative ultrasonography demonstrated dense vitritis and a thick elevated membrane-like lesion with internal patches of hyperechoic content attached to the inner ocular wall, suspected of a subretinal abscess in the inferior region. (supplementary material 7) Intraoperative findings showed a large subretinal abscess at the inferior region underneath the dense vitritis without posterior vitreous detachment. Lensectomy was done to improve visualization and to allow complete vitrectomy. Retinectomy and subretinal abscess removal were performed. After fluid air exchange, the retina was flattened and endolaser was applied around the retinectomy area. The eye was filled with heavy silicone oil (OxaneⓇ HD [Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA]) endotamponade. Ceftazidime was injected into the vitreous (2 mg/0.1 ml) and subconjunctival (100 mg/0.5 ml) at the end of the operation (Supplementary material 8).

After the surgery, inflammation and proptosis of the left eye were improved. A fibrous membrane or proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR) began to develop over the retinectomy area 1 week after the operation and increased over time. The vitreous sampling result could not show any organisms. During the hospital course, this patient was complicated by infection at other sites, which included ruptured liver abscess, rectal abscess with perforation, myositis, and abscess at the left leg. The specimens collected from all of these sites revealed K. pneumoniae. Because of these complications, intravenous antibiotics were given for 30 days and later switched to oral ciprofloxacin for 20 days.

One month after the surgery, BCVA was hand motion. The anterior and posterior segments were filled with the heavy silicone oil. Fundus examination showed fibrous membrane proliferation covering the retinectomy area. OCT showed generalized loss of ellipsoid zone and shallow subretinal fluid at the superior border of the retinectomy area. Three months after the operation, BCVA was stable at hand motion. The fibrous membrane increased and extended beyond the inferior macula and to optic nerve head, but the retina was remaining attached.

In summary, all patients had endogenous endophthalmitis with subretinal abscesses caused by K. pneumoniae with liver abscesses as the primary infection. The case series demonstrated increasing severity of the disease with Case 3 being the most severe and complicated by panophthalmitis. We provided stepwise management starting from less invasive to more invasive treatment depending on disease severity and treatment response. The outcome was satisfactory as the infection was eliminated in all cases and VA was well preserved in Case 1 and Case 2. Although the visual outcome in Case 3 was poor, the globe was salvaged even the infection was very severe with orbital tissue spreading.

Including the 3 cases of this study, there were 43 cases from 25 case reports and case series (see Table, Supplementary material 1–3, which illustrates previous publications and clinical data of K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscesses).Citation6–10,Citation12–31 The flow diagram of the literature search was illustrated (). There were 33 (76.7%) male and 10 (23.3%) female patients. The mean age was 49.5 ± 10.9 years. There were 7 cases with bilateral involvement resulting in a total of 50 eyes from 43 patients included in the analysis. Seven (16.3%) patients were healthy while 25 (58.1%) patients had diabetes mellitus. Of the 43 cases, 25 (58.1%) had liver abscess, 9 (20.9%) had bacteremia, 6 (14%) had urinary tract infection and respiratory tract infection, 4 (9.3%) had skin and muscle infection, 13 (30.2%) had multiple system involvement, and 3 (7%) had unidentified sources. A single patient might have more than one sites of infection.

The median time from ocular symptom onset to diagnosis is 2 days. The majority of patients had VA worse than 20/800. Hypopyon was often presented while one eye reported no anterior chamber inflammation. Vitritis was usually moderate to severe but clear vitreous could be observed in a few cases. Among 25 cases with the location of subretinal abscess being described, 9 eyes had macular involvement. K. pneumoniae was identified in different sources, vitreous in 17 cases (41.9%), blood in 26 cases (69.8%), liver abscess in 16 cases (37.2%), urine in 8 cases (18.6%), and abscess from other sites in 2 patients (4.6%). The clinical characteristics of the patients were summarized ().

Table 1. Summary of clinical characteristics of patients with K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess.

The treatment data were summarized (). Commonly used systemic antibiotics were third-generation cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, vancomycin, metronidazole, piperacillin/tazobactam, and meropenem. All patients received intravitreal antibiotics injections. Most common empirical intravitreal antibiotics were ceftazidime or amikacin combined with vancomycin. Others intravitreal drugs were fluoroquinolones, piperacillin/tazobactam, and ceftriaxone. Seven patients (14%) received systemic steroids in order to control inflammation, three patients (6%) received intravitreal steroids, and one patient received steroids by both routes. Six of the 11 patients who received steroids had favorable visual outcome, while 4 of them had poor final vision and 1 of them underwent eyeball removal. Thirty-seven of 50 eyes (74%) underwent vitrectomy: vitrectomy alone in 24 eyes, vitrectomy with retinotomy or retinectomy in 12 eyes, and vitrectomy combined with external drainage of subretinal abscesses in 1 eye. The median time from diagnosis to vitrectomy is 7.3 ± 11.9 days. The visual outcome was varied with VA better than or equal to 20/800 in 22 eyes (44%) and worse than 20/800 in 18 eyes (36%). Two eyes (4%) turned into phthisis bulbi and six eyes (12%) were enucleated/eviscerated. The most common complication was retinal detachment (19 eyes, 38%).

Table 2. Summary of treatments and outcomes of patients with K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess.

A subgroup analysis according to the final VA was performed (). Eyes with better final VA (≥20/800) demonstrated shorter median onset time to diagnosis compared with eyes with poorer final VA (p < 0.001). The eyes with better final VA also demonstrated better initial VA (p = 0.008), less severe vitritis (p < 0.001) and less involvement of the macula by subretinal abscesses (p = 0.033). However, the proportion of eyes that underwent PPV was not different between the two groups (72.7% vs 76.9%, p = 0.738).

Table 3. Subgroup analysis of K. pneumoniae subretinal abscess patient with good and poor final visual outcomes*.

Another subgroup analysis was done to compare vitrectomized group (37 eyes) and non-vitrectomized group (13 eyes) (). The vitrectomized group consisted of higher proportion of eyes with poor initial visual acuity (≤20/800) and severe vitritis, although statistical significance was not evident (p = 0.473 and p = 0.622, respectively). The final visual outcome was not different between the vitrectomized- and non-vitrectomized groups (p = 0.738). The proportion of eyeball removal including phthisis bulbi tended to be lower in the vitrectomized group but the difference was not statistically significant (10.8% vs 30.8%, p = 0.181). However, retinal detachment was more common in vitrectomized eyes (45.9%) compared with non-vitrectomized eyes (15.3%), yet the difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.095).

Table 4. Subgroup analysis of vitrectomy and non-vitrectomy groups.

Discussion

Subretinal abscess is a rare presentation of all endogenous endophthalmitis. In Klebsiella endogenous endophthalmitis, a subretinal abscess is not uncommon.Citation32 Subretinal abscess is associated with poor clinical outcomesCitation3 and the therapeutic approach of this condition is diverse. There were reviews of K. pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis focusing on prevalence, systemic source, treatment, and outcome. However, there was no review focusing on prognostic factors and therapeutic approaches for subretinal abscesses.

In this review, K. pneumoniae subretinal abscess was found predominately in males. The mean age of patients was approximately in the fifth decade of life. Overall demographic data were not different from previous studies. Diabetes mellitus is the most common comorbidity (58.1%). It has been reported as an important risk factor of K. pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis.Citation33 In addition, the most common systemic source is liver abscess (58.1%) which is similar to previous studies.Citation34,Citation35

In this study, we included only culture-proven patients. Blood cultures were positive in 69.8% and vitreous cultures were positive in 41.9%. These results were comparable to previous studies.Citation35,Citation36 However, vitreous sampling was negative in all three cases from our series. Vitreous tapping was performed after receiving intravenous antibiotics in all cases, and this could reduce the culture yield. Moreover, the volume of specimens from vitreous tapping was small. Larger volume of vitreous collected during vitrectomy could increase the chance of identifying the causative organisms. Although we collected the vitreous during vitrectomy in Case 2 and 3, the patients had already undergone vitreous tapping with intravitreal antibiotic injections, which could further explain the negative culture results.

The therapeutic approach for endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess is diverse. In general, the mainstay treatment for this condition is systemic intravenous antibiotics. They are necessary for controlling the primary infection source but most of them have poor ocular penetration. As a result, additional ocular management is needed.

Intravitreal antibiotic injection is usually considered as the initial ocular treatment.Citation36 It can rapidly deliver antibiotic levels in the vitreous to the therapeutic range. In the current review, all patients received intravitreal antibiotics and 13 of 50 eyes (26%) were treated by intravitreal antibiotics without vitrectomy. There were reports of cases of subretinal abscesses, which were successfully treated with serial intravitreal antibiotics injections alone.Citation22,Citation26,Citation37 We also demonstrated our patient with a subretinal abscess caused by K. pneumoniae who was successfully treated with serial intravitreal antibiotic injections without vitrectomy (Case 1). The treatment was started early and vitritis was mild. It should be noted that during treatment, subretinal exudation could temporarily increase and this was not a sign of disease worsening.

Vitrectomy in endophthalmitis can reduce loads of pathogens, clear the vitreous opacification, and increase drug distribution into the eye.Citation10,Citation38 There is no consensus about the time or cut-off point of VA for vitrectomy in endogenous endophthalmitis. Previous studies showed that early vitrectomy was associated with a lower rate of evisceration and enucleation and correlated with better final visual outcomes.Citation10,Citation33,Citation36,Citation39 In our study, the vitrectomized group had a nonsignificant lower rate of eyeball removal and phthisis bulbi. However, vitrectomy was not associated with a better final visual acuity. It should be noted that the percentage of patients with poor initial visual acuity and severe vitritis seemed higher in the vitrectomized group and this might affect the final visual acuity in these eyes. Moreover, retinal detachment rate tended to be higher in vitrectomized eyes. We suggested that vitrectomy should be considered in 1) patients unresponsive within 48 hours to an intravitreal injection, 2) patients with a high degree of ocular inflammation and 3) patients with poor initial BCVA.

There are additional concerns in subretinal abscesses. First, the photoreceptor overlying a subretinal abscess is rapidly lost as early as 48 hours.Citation14 Second, there are numerous pathogens in the abscess which are not cleared by vitrectomy alone. Retinotomy or retinectomy with subretinal abscess drainage in selected cases could be beneficial to eliminate the infectious source and the necrotic dysfunction retinal tissue. Furthermore, subretinal content could give a higher yield for microbiologic investigations.Citation40,Citation41 Harris et al. and Siu et al. reported two cases successfully treated by vitrectomy combined with retinectomy, subretinal abscess drainage, endolaser photocoagulation, and silicone oil tamponade. The infection was cleared after the surgery and vision was preserved; however, retinal detachment occurred postoperatively in both cases which needed reoperation.Citation6,Citation12 Other studies also demonstrated that vitrectomy and drainage of subretinal abscesses increased the risk of PVR and recurrent retinal detachment.Citation12,Citation42 A few studies suggested that retinectomy or retinotomy might be considered in the case with a subretinal abscess larger than 4 disc-diameter or the retina overlying the abscess was necrotic.Citation7,Citation38 According to our Case 3, early complete vitrectomy with retinectomy and subretinal abscess removal in very severe conditions such as a large subretinal abscess and panophthalmitis demonstrated benefits for eliminating the infection and securing the anatomical outcome.

Vitrectomy in this condition is challenging. Even with successful surgery and treatment, retinal detachment could occur in both acute and late stages.Citation10,Citation21,Citation43 In this study, the rate of retinal detachment was higher in vitrectomized eyes. Although the difference did not reach statistical significance (with limited number of cases available for analyses), the risk and benefit of vitrectomy must be weighed. Thorough preoperative assessment including clinical examination and ultrasonography should be done to avoid complications. In addition, close monitoring after vitrectomy was necessary due to the high risk of necrotic retinal breaks and RRD as demonstrated in our Case 2. Surgical intervention for RRD should be promptly performed when it occurred.

K. pneumoniae is a high-virulence organism that can rapidly deteriorate photoreceptors and forms a subretinal abscess in the early stage. Therefore, endogenous endophthalmitis caused by K. pneumoniae had a poorer visual prognosis compared with other pathogens.Citation35 Moreover, subretinal abscess itself was related to a poor prognosis.Citation32 This review demonstrated that a better final VA was related to a better initial VA, earlier diagnosis and a lower degree of vitritis at presentation. These prognostic factors were in agreement with other studies of endogenous endophthalmitis.Citation32,Citation34,Citation35,Citation44,Citation45 In addition, we also found that macular involvement of subretinal abscess was significantly related to a poor visual outcome.

There were some mentionable limitations. This review summarized only case reports and case series due to the disease rarity. The sample size was limited, despite the comprehensive inclusion of cases from the literature. Lack of required information from the literature review and inaccessibility of non-English data could result in incomplete data.

Conclusions

K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis with subretinal abscess is a serious ocular infection. The clinical presentations were varied from mild to severe degree of inflammation and infection. About half of all patients had poor final visual acuity (less than 20/800). Prompt treatment especially when the degree of inflammation was mild with relatively good VA was crucial for a better visual outcome. The mainstay therapy for these cases included systemic and intravitreal antibiotics. This could adequately control the infection in the early course of disease showing mild degree of vitritis and drainage of abscess was not required. Vitrectomy should be considered in patients who do not respond to intravitreal antibiotics or in cases with more severe inflammation to reduce eyeball removal and phthisis bulbi rate. However, vitrectomy was not related to good final visual acuity and retinal detachment tended to be more common in the vitrectomized eyes.

Authors contributions

All authors were involved in the conception of the study and research design. CM NP and NW were involved in data acquisition. CM and NP did the literature review and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (2 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chulaluk Komoltri, PhD for assistance in statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09273948.2023.2221341.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shrader SK, Band JD, Lauter CB, Murphy P. The clinical spectrum of endophthalmitis: incidence, predisposing factors, and features influencing outcome. J Infect Dis. 1990;162(1):115–120. doi:10.1093/infdis/162.1.115.

- Chee SP, Jap A. Endogenous endophthalmitis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2001;12(6):464–470. doi:10.1097/00055735-200112000-00012.

- Jolly SS, Brownstein S. Endogeneous Nocardia subretinal abscess. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago,Ill: 1960). 1996;114(9):1147–1148. doi:10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140349023.

- Hussain I, Ishrat S, Ho DCW, Khan SR, Veeraraghavan MA, Palraj BR, et al. Endogenous endophthalmitis in Klebsiella pneumoniae pyogenic liver abscess: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;101:259–268. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.09.1485.

- Spelta S, Di Zazzo A, Antonini M, Bonini S, Coassin M. Does endogenous endophthalmitis need a more aggressive treatment? Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(5):937–943. doi:10.1080/09273948.2019.1705497.

- Siu GD, Lo EC, Young A. Endogenous endophthalmitis with a visual acuity of 6/6. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015(Mar18 1):bcr2014205048. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-205048.

- Xu H, Fu B, Lu C, Xu L, Sun J. Successful treatment of endogenous endophthalmitis with extensive subretinal abscess: a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018;18(1):238. doi:10.1186/s12886-018-0908-x.

- Mohd-Ilham I, Zulkifli M, Yaakub M, Muda R, Shatriah I. A case of a large sub-retinal abscess secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis in a pyelonephritis patient. Cureus. 2019;11(5):e4656. doi:10.7759/cureus.4656.

- Bouhout S, Lacourse M, Labbé AC, Aubin MJ. A rare presentation of Klebsiella pneumoniae endogenous panophthalmitis with optic neuritis and orbital cellulitis from a urinary tract infection. IDCases. 2021;26:e01289. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01289.

- Yoon YH, Lee SU, Sohn JH, Lee SE. Result of early vitrectomy for endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis. Retina. 2003;23(3):366–370. doi:10.1097/00006982-200306000-00013.

- Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23(2):60. doi:10.1136/bmjebm-2017-110853.

- Harris EW, D’Amico DJ, Bhisitkul R, Priebe GP, Petersen R. Bacterial subretinal abscess: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(6):778–785. doi:10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00355-X.

- Yao TC, Hung IJ, Su LH, Chiu CH. Endogenous endophthalmitis and necrotising pneumonia caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae in a child with beta-thalassaemia major. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160(7):449. doi:10.1007/s004310100764.

- Christoforidis JB, Warden SM, Farrell GM, Baker M, Mukai S. Histology of retina overlying bacterial subretinal abscess and implications for treatment. Retinal Cases Brief Rep. 2007;1(4):257–260. doi:10.1097/01.iae.0000238381.27024.d1.

- Yang CS, Tsai HY, Sung CS, Lin KH, Lee FL, Hsu WM. Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis associated with pyogenic liver abscess. Ophthalmol. 2007;114(5):876–880. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.035.

- Tsai AS, Lee SY, Jap AH. An unusual case of recurrent endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis. Eye (Lond). 2010;24(10):1630–1631. doi:10.1038/eye.2010.95.

- Suwan Y, Preechawai P. Endogenous Klebsiella panophthalmitis: atypical presentation. J Med Assoc Thai. 2012;95:830–833.

- Kashani AH, Eliott D. The emergence of Klebsiella pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis in the USA: basic and clinical advances. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2013;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/1869-5760-3-28.

- Sachdev DD, Yin MT, Horowitz JD, Mukkamala SK, Lee SE, Ratner AJ. Klebsiella pneumoniae K1 liver abscess and septic endophthalmitis in a U.S. resident. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51(3):1049–1051. doi:10.1128/JCM.02853-12.

- Sridhar J, Flynn HW Jr., Kuriyan AE, Dubovy S, Miller D. Endophthalmitis caused by Klebsiella species. Retina. 2014;34(9):1875–1881. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000000162.

- Kimura D, Sato T, Suzuki H, Kohmoto R, Fukumoto M, Tajiri K, et al. A case of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment at late stage following endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2017;8(2):334–340. doi:10.1159/000477160.

- Martel A, Butet B, Ramel JC, Martiano D, Baillif S. Medical management of a subretinal Klebsiella pneumoniae abscess with excellent visual outcome without performing vitrectomy. J francais d’ophtalmol. 2017;40(10):876–881. doi:10.1016/j.jfo.2017.06.007.

- Odouard C, Ong D, Shah PR, Gin T, Allen PJ, Downie J, et al. Rising trends of endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis in Australia. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2017;45(2):135–142. doi:10.1111/ceo.12827.

- Shields RA, Smith SJ, Pan CK, Do DV. Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis in Northern California. Retina. 2019;39(3):614–620. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000001994.

- Castle G, Heath G. Endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis as the presentation of both Klebsiella liver abscess and underlying anti-IFN-3 autoimmunity. Access Microbiol. 2020;2(11):acmi000164. doi:10.1099/acmi.0.000164.

- Dogra M, Singh SR, Thattaruthody F. Klebsiella pneumoniae endogenous endophthalmitis mimicking a choroidal neovascular membrane with subretinal hemorrhage. Ocul Immunol Inflammation. 2020;28(3):468–470. doi:10.1080/09273948.2019.1569695.

- Lim SW, Sung Y, Kwon HJ, Song WK. Endogenous endophthalmitis associated with liver abscess successfully treated with vitrectomy and intravitreal empirical antibiotics injections. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2020;2020:8165216. doi:10.1155/2020/8165216.

- Mak CY, Ho M, Iu LP, Sin HP, Chen LJ, Lui G, et al. Clinical features and treatment outcomes of endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis: a 12-year review. Int J Ophthalmol. 2020;13(12):1933–1940. doi:10.18240/ijo.2020.12.14.

- Shen C, Chaudhary V. Endogenous bacterial chorioretinal abscess presenting with unusual retinal pigment epithelial excrescences and large subretinal hemorrhage. Retina. 2020;40(6):e28–e9. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002841.

- Chelvaraj R, Thamotaran T, Yee CM, Fong CM, Zhe NQ, Azhany Y. The invasive Klebsiella pneumoniae syndrome: case series. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2022;17(2):332–339. doi:10.1016/j.jtumed.2021.10.012.

- Fan KC, Patel NA, Sengillo JD, Hudson JL, Davis JL. Concomitant pyogenic liver and intraocular abscesses in Klebsiella endogenous endophthalmitis: case report and review of literature. Retinal Cases Brief Rep. 2022;16(6):691–693. doi:10.1097/ICB.0000000000001075.

- Chen YH, Li YH, Lin YJ, Chen YP, Wang NK, Chao AN, et al. Prognostic factors and visual outcomes of pyogenic liver abscess-related endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis: a 20-year retrospective review. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1071. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37643-y.

- Sheu SJ, Kung YH, Wu TT, Chang FP, Horng YH. Risk factors for endogenous endophthalmitis secondary to Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess: 20-year experience in Southern Taiwan. Retina. 2011;31(10):2026–2031. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820d3f9e.

- Chen YJ, Kuo HK, Wu PC, Kuo ML, Tsai HH, Liu CC, et al. A 10-year comparison of endogenous endophthalmitis outcomes: an east Asian experience with Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Retina. 2004;24(3):383–390. doi:10.1097/00006982-200406000-00008.

- Chen SC, Lee YY, Chen YH, Lin HS, Wu TT, Sheu SJ. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection leads to a poor visual outcome in endogenous endophthalmitis: a 12-year experience in Southern Taiwan. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;25(6):870–877. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1193616.

- Jackson TL, Paraskevopoulos T, Georgalas I. Systematic review of 342 cases of endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014;59(6):627–635. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2014.06.002.

- Scavelli K, Li Y, Carroll R, Kim BJ. Resolution of subretinal abscess from presumed Nocardia chorioretinitis with serial intravitreal amikacin. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019;16:100540. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2019.100540.

- Tsai TH, Peng KL. Metastatic endophthalmitis combined with subretinal abscess in a patient with diabetes mellitus—a case report. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15(1):105. doi:10.1186/s12886-015-0079-y.

- Lee S, Um T, Joe SG, Hwang JU, Kim JG, Yoon YH, et al. Changes in the clinical features and prognostic factors of endogenous endophthalmitis: fifteen years of clinical experience in Korea. Retina. 2012;32(5):977–984. doi:10.1097/IAE.0b013e318228e312.

- Verma S, Azad SV, Venkatesh P, Kumar V, Surve A, Balaji A, et al. Role of intralesional antibiotic for treatment of subretinal abscess – case report and literature review. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;30(2):1–4. doi:10.1080/09273948.2020.1811880.

- Venkatesh P, Temkar S, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Intralesional antibiotic injection using 41G needle for the management of subretinal abscess in endogenous endophthalmitis. Int J Retin Vitr. 2016;2(1):17. doi:10.1186/s40942-016-0043-x.

- Webber SK, Andrews RA, Gillie RF, Cottrell DG, Agarwal K. Subretinal Pseudomonas abscess after lung transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(9):861–866. doi:10.1136/bjo.79.9.861.

- Lingappan A, Wykoff CC, Albini TA, Miller D, Pathengay A, Davis JL, et al. Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis: causative organisms, management strategies, and visual acuity outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;153(1):162–6 e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2011.06.020.

- Lourthai P, Choopong P, Dhirachaikulpanich D, Soraprajum K, Pinitpuwadol W, Punyayingyong N, et al. Visual outcome of endogenous endophthalmitis in Thailand. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):14313. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-93730-7.

- Silpa-Archa S, Ponwong A, Preble JM, Foster CS. Culture-positive endogenous endophthalmitis: an eleven-year retrospective study in the central region of Thailand. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(4):533–542. doi:10.1080/09273948.2017.1355469.