ABSTRACT

Purpose

Uveitis is a common ocular manifestation in individuals with sarcoidosis, a multisystem inflammatory disorder. This study aimed to explore clinical and genetic factors associated with the presence or absence of uveitis in sarcoidosis patients.

Methods

Total 625 Dutch sarcoidosis patients were included. Among these, 170 underwent ophthalmic examination, and 61 were diagnosed with uveitis. Demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, race, biopsy status, chest radiography findings, TNF-α inhibitor treatment, and uveitis classification were collected retrospectively from medical records. Genetic data was available for HLA haplotypes, TNF-α G-308A, and BTNL2 G16071A polymorphisms.

Results

The majority of the patients presented with bilateral uveitis (80.3%). The proportion of women was higher in the uveitis group compared to the non-uveitis group (67.2% and 47.7%; p = 0.014). Pulmonary involvement (chest radiographic stage II-III) was significantly lower in patients with uveitis (36.1% versus 64.2%; p < 0.001). Patients with uveitis were more often treated with TNF-α inhibitors (67.2% versus 29.4%; p < 0.001) and the outcome was better compared with the non-uveitis group, 92% vs 68%, responders (p < 0.012). Uveitis patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors (either adalimumab or infliximab) were more likely to suffer from intermediate or posterior uveitis than anterior uveitis. Genetic analysis identified a significant association between the BTNL2 G16071A GG genotype and uveitis (p = 0.012).

Conclusion

This study highlights distinctive demographic, clinical and genetic features associated with uveitis in sarcoidosis patients. Ocular sarcoidosis was more prevalent in women. Further research is warranted to explore the implications of these findings for treatment strategies and prognostic assessments.

Sarcoidosis is a multi-organ inflammatory condition. It can involve any, and more commonly multiple, organs of the body, and often manifests with an array of symptoms.Citation1,Citation2 Like the presentation and symptoms of sarcoidosis, patients’ functional limitations are highly diverse.Citation2 Sarcoidosis typically affects young and middle-aged adults, with a peak incidence at 30–50 years of age in men and 50–60 years of age in women.Citation3

Systemic sarcoidosis includes ocular sarcoidosis, which may represent the initial presenting symptom in a substantial number of cases. Ocular sarcoidosis can present in any structure of the eye. The most common manifestations of ocular sarcoidosis include uveitis, conjunctival nodules, and lacrimal gland involvement.Citation4,Citation5 Sarcoid uveitis is most frequently bilateral, with similar characteristics and clinical course in both eyes.Citation6 The prevalence of ocular involvement in sarcoidosis varies between 10 and 50% in Caucasian sarcoidosis patients.Citation7–10 Higher frequencies have been observed in the Japanese population.Citation11,Citation12 African-Americans are younger at ophthalmic presentation than Caucasian patients.Citation13 In a Dutch mixed-race population, uveitis was more common in the Black members, while Caucasians were more likely to have posterior uveitis.Citation14 Many potential causes of sarcoidosis have been suggested, genetic susceptibility is implicated. Previous studies were focusing on pulmonary activity. Genetic susceptibility to uveitis in general has been well studied. However, investigations into genetic susceptibility to uveitis in the context of sarcoidosis remain limited.Citation15

Among the genetic factors identified, the tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) G-308A (rs1800629) single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) has been linked to sarcoidosis.Citation16,Citation17,Citation18 TNF-α, a key pro-inflammatory cytokine, plays a crucial role in inflammatory responses, cytokine production, neutrophil activation, and granuloma formation. Other genes or SNPs, such as the butyrophilin-like 2 (BTNL2) G16071A (rs2076530) SNP, and various human leucocyte antigens (HLA), have also been associated with sarcoidosis.Citation16,Citation19,Citation20

This study aimed to identify the uveitis patterns in sarcoidosis patients, and compare their clinical presentation with that of sarcoidosis patients without uveitis, to shed light on the intricate relationship between genetic factors and ocular involvement in sarcoidosis.

Materials and methods

Study design

A single-centre retrospective study was conducted. This study included a cohort of Dutch sarcoidosis patients attending the outpatient referral clinic of the Sarcoidosis Management Centre (SMC) of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC) between January 2000 and July 2008. The SMC Maastricht, a tertiary referral center in the Netherlands, was part of the Department of Respiratory Medicine from 2000–2012, focusing specifically on the multidimensional character of sarcoidosis, so as to enhance patient care efficiency.Citation21 The SMC Maastricht assembled a diverse multidisciplinary team consisting of experts from various medical and paramedical fields. This team included specialists such as pulmonologists, cardiologists, rheumatologists, internists, dermatologists, radiologists, pathologists, ophthalmologists, neurologists, immunologists, ear, nose and throat physicians, toxicologists, clinical genetics counsellors, and physical therapists. Patients with sarcoidosis in Maastricht underwent initial assessments by various specialists. Additionally, all patients received evaluations from a pulmonologist within the SMC team, and when necessary from other team members as well.Citation21 Patients were referred to the ophthalmologist if they had any symptoms such as eye pain, redness of the eye, blurry vision, and/or sensitivity to light, in order to evaluate whether they had uveitis.

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis was established according to the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous diseases (WASOG) guidelines,Citation22 as well as the more recently published criteria of the Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline.Citation23 The diagnosis was based on a positive biopsy in 65% of cases. For patients with typical features of Löfgren’s syndrome and characteristic features in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid analysis results, no biopsy was obtained. Only those sarcoidosis patients who had an ophthalmic examination at the University Eye Clinic, MUMC, Maastricht, The Netherlands, were included.

The Medical Ethics Board of the MUMC approved the protocol (METC 11-4-116). This cohort and the methods have previously been described in more detail.Citation16 The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments.

Collection of clinical data

Pulmonary involvement was determined using chest X-rays. All chest X-rays were graded by a single observer, who was unaware of the clinical data. The chest X-rays were divided into five stages: stage 0 (normal X-ray), stage I (bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy [BHL]), stage II (BHL and parenchymal abnormalities), stage III (parenchymal abnormalities without BHL) and stage IV (end stage lung fibrosis).Citation2,Citation23

Uveitis was diagnosed and classified according to the anatomic classification of the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature (SUN) working group.Citation24,Citation25 The uveitis was divided into anterior, intermediate, posterior and panuveitis. Moreover, in the presence of mutton-fat keratic precipitates, iris granulomas and/or granulomas on fundoscopic examination, the uveitis was classified as granulomatous. If these features were absent, the uveitis was classified as nongranulomatous.Citation5,Citation26 All patients with uveitis were seen by a single uveitis specialist (RE) of the University Eye Clinic, MUMC, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Genotyping

TNF-α and BTNL2 genotyping

Venous EDTA-anticoagulated blood and isolated with a High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions was used to obtain DNA. The patients were genotyped for the TNF-α promotor G-308A (rs1800629) and BTNL2 G16071A (rs2076530) SNPs. Real-time PCR fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assays (TIB MOLBIOL, Berlin, Germany) were performed as described by Bestman et al. on the LightCycler® (Roche Diagnostics) for genotyping.Citation27 The analyses were performed by an analyst blinded to the clinical data used for the classification of the patients.

HLA

QIA-AMP kits were used, following the supplier’s protocol (Qiagen, Westburg, Leusden, The Netherlands), for genomic DNA isolation. Concentration and purity of DNA samples were measured at 260 nm and 260/280 nm, respectively. Low-resolution typing of HLA-DRB1 was performed using Luminex reverse SSO, with bead kits from One Lambda (One Lambda, Bethesda, MD) or using PCR-SSP with 45 in-house primer mixes as described previously.Citation28

Statistical analysis

SPSS 28.0 (SPSS INC., Chicago, IL) was used for the statistical analysis. The chi-squared test was used to test for statistically significant differences between groups. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios (OR, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and deviations from the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium were analysed using the chi-squared test.

Results

All 625 sarcoidosis patients were seen by a pulmonologist of the SMC of the MUMC. Of the 170 who had an ophthalmic examination, 61 were diagnosed with uveitis (see ). The majority of these sarcoidosis patients were Caucasian. Twenty-five of the patients with uveitis were initially seen by an ophthalmologist and subsequently referred to a pulmonologist of the SMC of the MUMC to confirm the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The remaining 36 were first examined by a pulmonologist who established the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, and thereafter referred to the ophthalmologist (see ). Of the 61 uveitis patients, 25 were initially seen by the ophthalmologist. Seven of these uveitis patients (28%) had a normal chest X-ray. Of those initially seen by the pulmonologist (n = 36), 17 (47%) had a normal chest X-ray (see also ). Patients without uveitis were more likely to undergo a biopsy in the diagnostic workup, compared to those with uveitis (p < 0.001). The majority of patients with uveitis had an abnormal chest X-ray (60.7%). In patients with uveitis, pulmonary involvement (CXR stage II-III) was less common than in those without uveitis (p < 0.001). Moreover, only 9.9% of the sarcoidosis patients with uveitis had CXR stage III, compared to 21.1% (p = 0.061) of those without uveitis, indicating a worse prognosis (). Furthermore, patients with uveitis were more often treated with TNF-α inhibitors (41/61 (67.2%)) than those without uveitis (32/109 (29.4%); p < 0.001). No other clinical differences were found between the patients with and without uveitis. The 455 sarcoidosis patients who were not referred to the ophthalmologist had clinical and demographic data similar to those in the non-uveitis group (data not shown). Overall, 10% (61/625) of our Dutch sarcoidosis patients were diagnosed with uveitis.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the selection of sarcoidosis patients with an ophthalmic examination, with and without uveitis.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sarcoidosis patients with and without uveitis.

lists the characteristics of the uveitis patients subdivided into treatment with TNF-α inhibitors, yes or no. The majority of the patients with uveitis presented with bilateral uveitis (49/61 = 80.3%). There was no significant difference in bilateral involvement rate between the patients treated with or without TNF-α inhibitors.

Table 2. Characteristics of uveitis patients with or without tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha inhibitor treatment.

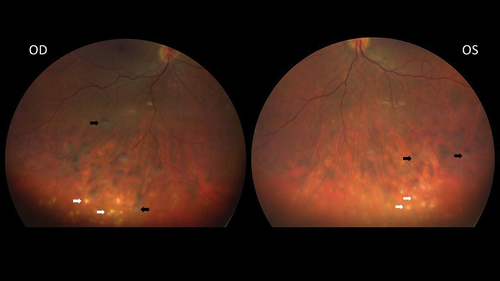

Of the 61 patients with uveitis, 41 (67.2%) were female, with an OR of 2.25 (95% CI: 1.17–4.32). show fundus images (2) as well as fluorescein angiograms (3) of both eyes of a 32-year old female sarcoidosis patient suffering from bilateral panuveitis. Thirty uveitis patients presented with granulomatous uveitis, 31 with nongranulomatous uveitis. The localization of the uveitis varied between patients with granulomatous uveitis and those with nongranulomatous uveitis. Those with granulomatous uveitis were less likely to present with anterior uveitis (2 versus 10; p = 0.022). Of the patients with granulomatous uveitis 76.6% were treated with TNF-α-inhibitors compared with 58.1% of those with nongranulomatous uveitis (p = 0.17). Comparing the two groups did not reveal other significant clinical differences.

Figure 2. Fundus images of both eyes of a 32-year-old female sarcoidosis patient with bilateral panuveitis. The black arrows indicate snowballs, the white arrows indicate multiple atrophic chorioretinal lesions.

Of the 41 uveitis patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors, 29 (70.7%) were initially treated with adalimumab and 12 (29.3%) with infliximab. Patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors were also treated with low-dose methotrexate (5–7.5 mg weekly) and/or low-dose oral glucocorticosteroids (5 mg daily). In case patients treated with MTX developed adverse drug reactions, the treatment was changed to either azathioprine (n = 3) or Cellcept (n = 2).

Of the 21 (34.4%) patients presenting with intermediate uveitis, the majority (90.5%) were treated with TNF-α inhibitors. Of the 12 patients presenting with anterior uveitis only one third was treated with TNF-α inhibitors. Moreover, there was a significant difference in the type of uveitis between the different treatment groups, as patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors more often had intermediate or posterior uveitis (68.3%), while patients not treated with TNF-α inhibitors mostly had anterior uveitis (40%). The latter patients were treated either with topical steroids (n = 8) or with oral prednisone (n = 12), in some cases combined with another immunomodulatory agent.

The response rate of uveitis patients treated with TNF-α-inhibitors was higher than that of non-uveitis patients: 92% vs 68% (p = 0.012). Due to the retrospective character of the present study, we only had access to follow-up data of the non-uveitis patients who were treated with TNF-α inhibitors.

Figure 3. Fluorescein angiogram of both eyes of the same sarcoidosis patient with bilateral panuveitis. The black arrows indicate vascular leakage, the white arrows indicate hyperfluorescent dots corresponding to multiple atrophic chorioretinal lesions.

presents the genetic features of the groups with and without uveitis. No statistically significant differences were found between these two groups as to HLA haplotypes or TNF-α G-308A genotypes. The groups differed in BTNL2 G16071A genotypes, the GG genotype being more prevalent in sarcoidosis patients with uveitis, with an OR of 3.49 (95% CI: 1.26–9.64).

Table 3. Some relevant polymorphisms in sarcoidosis patients with and without uveitis.

Discussion

This retrospective study aimed to investigate the clinical and genetic characteristics of sarcoidosis patients with and without uveitis. A total of 170 patients seen by an ophthalmologist were included, resulting in a diagnosis of uveitis in 61 cases, of whom the majority (80.3%) bilateral. Comparative analyses were conducted on demographic, clinical, and genetic features between the two groups. Results revealed a significant difference in gender distribution, with a predominance of female patients in the uveitis group, as well as differences in chest radiography findings, with less pulmonary involvement in patients with uveitis, and less frequent treatment with TNF-α inhibitors in patients without uveitis. Additionally, genetic analyses demonstrated a notable association between the BTNL2 G16071A GG genotype and sarcoidosis patients with uveitis. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the distinct characteristics associated with uveitis in sarcoidosis patients.

We observed that the most common type of uveitis was intermediate uveitis. The majority of patients treated with TNF-α inhibitors had intermediate or posterior uveitis, whereas patients treated without TNF-α inhibitors more often presented with anterior uveitis. Earlier studies showed varying prevalences of the types of uveitis.Citation29 Traditionally, the most common type of uveitis associated with sarcoidosis has been reported to be anterior uveitis (up to 75%).Citation4,Citation30 It should be noted, however, that in these studies the majority of patients were Black. In Caucasian populations, posterior uveitis was the most commonly reported type of uveitis (65–83%), especially in elderly women.Citation4 In accordance with the literature, the majority of our patients had bilateral uveitis (80.3%).Citation6

Uveitis is generally more common in women than in men, and this difference becomes more prominent with increasing age. The results of our study are in line with those of others, who have also found a female predominance in sarcoid uveitis.Citation14,Citation31–34 However, systemic sarcoidosis affects both genders equally, being only slightly more predominant in women than in men.Citation34–36 Recent studies of sarcoidosis indicate an interaction between the immune system, reproductive hormones, genetic and epigenetic modifications, stress, and also environmental factors.Citation37,Citation38

In our study, 60.7% of patients with uveitis showed chest X-ray abnormalities. In line with this, Takase recommended that, in cases of so far unexplained uveitis, ophthalmologists should perform systemic investigations, including a chest X-ray, and consult other specialists, especially pulmonologists.Citation39 Establishing a treatment indication in sarcoidosis also requires a thorough work-up. Parenchymal pulmonary involvement, i.e. chest X-ray stage II-IV, was less common in our uveitis patients (36.1%) compared to the sarcoidosis patients without uveitis (64.2%). This is in line with a recent study by Lee et al. who also reported that the presence of parenchymal pulmonary lesions was associated with a lower incidence of uveitis.Citation40 Others also found less pulmonary involvement in sarcoidosis patients with uveitis.Citation13,Citation30,Citation41,Citation42 Interestingly, Evans et al. found more pulmonary involvement (62%) in their sample of Black sarcoidosis patients.Citation13 Black race is an adverse prognostic factor in sarcoidosis.Citation2 Allegri et al. reported on a sample of 215 patients with uveitis who underwent a high resolution CT-scan (HRCT), with 40.0% showing parenchymal pulmonary involvement and 13.2% showing a combination with BHL (chest X-ray stage II).Citation43 However, the lack of uniform criteria for assessing pulmonary involvement in different studies introduces a challenge in comparing our study results with existing literature. Some studies assume lung involvement if BHL and/or pulmonary infiltration is present.Citation44–46 This means that CXR stages I-IV are all considered to reflect pulmonary involvement. Based on the criteria of the CXR scoring system, only CXR stages II-IV should strictly speaking be considered to reflect pulmonary involvement.Citation2,Citation23 However, distinguishing the presence of BHL (stage I or II) is important, as these sarcoidosis manifestations have a more favourable prognosis than CXR stages III and IV.Citation2 Lee et al. also found that the presence of ophthalmic symptoms was associated with uveitis, highlighting the fact that sarcoidosis patients experiencing these symptoms should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist. Moreover, they found that even in the absence of lung parenchymal lesions, patients diagnosed with sarcoidosis involving lymph nodes (Chest X-ray stage I) may benefit from ophthalmic screening examinations for uveitis.Citation40

In a previous study by our group, we found that TNF-α inhibitors were effective in the treatment of refractory chronic sarcoid uveitis.Citation47 Our experience is that the treatment of ocular sarcoidosis with immunosuppressives also benefits other sarcoidosis manifestations. Furthermore, in accordance with Yong Choi et al. the rate of treatment with TNF-α inhibitors in our sarcoidosis-associated uveitis group was high compared to the group without uveitis.Citation48 During the largest part of the study period, the TNF-α inhibitor adalimumab, was only authorized for the treatment of uveitis in the Netherlands, and not for the treatment of sarcoidosis in general.

A recent study by Rasmussen et al. showed an association between sarcoidosis and HLA-DRB1 × 03:01 and HLA-DRB1 × 04:01 in a large cohort.Citation49 Another study showed a correlation between HLA-DRB *03:01, *11:01 and 12:01 and sarcoidosis in general.Citation50 In our study no statistically significant difference between the groups with and without uveitis was found regarding HLA-DRB *03:01.

Different polymorphisms of the TNF-α gene have been associated with varying prognoses, with the TNF-α G-308A SNP, more specifically the AA genotype, having been associated with Löfgren’s syndrome.Citation17,Citation51 Löfgren’s syndrome is a manifestation of sarcoidosis with a generally favourable prognosis.Citation2 The AG/GG genotypes are associated with an increased risk of sarcoidosis, whereas the TNF-α G-308A AA genotype was observed in 44.0% of patients with non-persistent disease compared to 25.5% of patients with persistent pulmonary disease.Citation16 In our study no statistically significant difference was found between the two groups regarding TNF-α G-308A.

The functional BTNL2 protein reduces the proliferation of, and the cytokine production by, activated T-cells. This suggests a role for BTNL2 as a negative costimulatory molecule. The BTNL2 G16071A SNP has shown the strongest association with sarcoidosis. An association between SNPs in the BTNL2 gene and the risk of developing sarcoidosis has been shown in previous studies.Citation20,Citation52–54 We found a statistically significance difference in BTNL2 G16071A between the two groups, with the GG genotype being more prevalent in sarcoidosis patients with uveitis. A study in Japan also found an association between sarcoidosis and BTNL2 G16071A, but no statistically significant difference in allele frequencies between patients with and without ocular involvement.Citation55 Previously, it was found that the AA/AG haplotype increases sarcoidosis risk and almost doubles the risk of progressing to persistent pulmonary disease, which is in line with our findings.Citation19

One of the limitation of the present study is that all patients were recruited from a tertiary referral center. This could have led to selection bias, since the patients referred to tertiary referral centres often represent more complex cases (in terms of affected organs and symptoms). However, the MUMC is the only hospital in Maastricht. Only 170 of the 625 sarcoidosis patients were examined by an ophthalmologist. Although the remaining 455 sarcoidosis patients did not have any symptoms associated with eye involvement, asymptomatic uveitis cases could have been missed.

Hence, our results may not be generalizable to all sarcoidosis patients. However, our results concerning the prevalence of uveitis in sarcoidosis are in line with those of other studies in European sarcoidosis patient samples.Citation4,Citation10,Citation13,Citation56,Citation57 Another limitation is its retrospective design that is associated with missing data. Moreover, important detailed information about environmental exposure was lacking. We are therefore planning a follow-up study to explore the presence of occupational as well as environmental exposures in patients with uveitis, including sarcoidosis-associated uveitis.

In conclusion, this study highlights distinctive demographic, clinical, and genetic features associated with uveitis in sarcoidosis patients. Ocular sarcoidosis was more prevalent in women in our Dutch cohort. The explanation for this is still not clear and future studies are needed to explore whether specific triggers present in women may contribute to the gender difference. The BTNL2 G16071A GG genotype was significantly more prevalent in sarcoidosis patients with uveitis. Chest X-ray abnormalities were present in 60.7% of our uveitis patients, with only 9.9% associated with a worse prognosis (chest X-ray stage III). Further research is warranted to explore the implications of these findings for management strategies and prognostic assessments in sarcoidosis patients with uveitis.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ild care foundation (www.ildcare.nl).

We thank Tos Berendschot for statistical advice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Drent M, Costabel U, Crouser ED, Grunewald J, Bonella F. Misconceptions regarding symptoms of sarcoidosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(8):816–818. doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00311-8.

- Drent M, Crouser ED, Grunewald J. Challenges of sarcoidosis and its management. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(11):1018–1032. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2101555.

- Arkema EV, Cozier YC. Sarcoidosis epidemiology: recent estimates of incidence, prevalence and risk factors. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2020;26(5):527–534. doi:10.1097/MCP.0000000000000715.

- Rothova A. Ocular involvement in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84(1):110–116. doi:10.1136/bjo.84.1.110.

- Giorgiutti S, Jacquot R, El Jammal T, Bert A, Jamilloux Y, Kodjikian L, et al. Sarcoidosis-related uveitis: a review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(9):3194. doi:10.3390/jcm12093194.

- El Jammal T, Loria O, Jamilloux Y, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Kodjikian L, Seve P. Uveitis as an open window to systemic inflammatory diseases. J Clin Med. 2021;10(2). doi:10.3390/jcm10020281.

- James DG, Anderson R, Langley D, Ainslie D. Ocular sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1964;48(9):461–470. doi:10.1136/bjo.48.9.461.

- Karma A, Huhti E, Poukkula A. Course and outcome of ocular sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106(4):467–472. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(88)90885-9.

- Jabs DA, Johns CJ. Ocular involvement in chronic sarcoidosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102(3):297–301. doi:10.1016/0002-9394(86)90001-2.

- Crick RP, Hoyle C, Smellie H. The eyes in sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1961;45(7):461–481. doi:10.1136/bjo.45.7.461.

- Morvan M, Nourine L. Simplicial elimination schemes, extremal lattices and maximal antichain lattices. 1996.

- Morimoto T, Azuma A, Abe S, Usuki J, Kudoh S, Sugisaki K, et al. Epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Japan. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):372–379. doi:10.1183/09031936.00075307.

- Evans M, Sharma O, LaBree L, Smith RE, Rao NA. Differences in clinical findings between Caucasians and African Americans with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):325–333. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.074.

- Rothova A, Alberts C, Glasius E, Kijlstra A, Buitenhuis HJ, Breebaart AC. Risk factors for ocular sarcoidosis. Doc Ophthalmol. 1989;72(3–4):287–296. doi:10.1007/BF00153496.

- Huang XF, Brown MA. Progress in the genetics of uveitis. Genes Immun. 2022;23(2):57–65. doi:10.1038/s41435-022-00168-6.

- Wijnen PA, Nelemans PJ, Verschakelen JA, Bekers O, Voorter CE, Drent M. The role of tumor necrosis factor alpha G-308A polymorphisms in the course of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Tissue Antigens. 2010;75(3):262–268. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01437.x.

- Swider C, Schnittger L, Bogunia-Kubik K, Gerdes J, Flad H, Lange A, et al. TNF-alpha and HLA-DR genotyping as potential prognostic markers in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1999;10(2):143–146.

- Medica I, Kastrin A, Maver A, Peterlin B. Role of genetic polymorphisms in ACE and TNF-alpha gene in sarcoidosis: a meta-analysis. J Hum Genet. 2007;52(10):836–847. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0185-7.

- Wijnen PA, Voorter CE, Nelemans PJ, Verschakelen JA, Bekers O, Drent M. Butyrophilin-like 2 in pulmonary sarcoidosis: a factor for susceptibility and progression? Hum Immunol. 2011;72(4):342–347. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2011.01.011.

- Rybicki BA, Walewski JL, Maliarik MJ, Kian H, Iannuzzi MC, Group AR. The BTNL2 gene and sarcoidosis susceptibility in African Americans and Whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(3):491–499. doi:10.1086/444435.

- Drent M. Sarcoidosis: benefits of a multidisciplinary approach. Eur J Intern Med. 2003;14(4):217–220. doi:10.1016/s0953-6205(03)00076-1.

- Statement on Sarcoidosis. Joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(2):736–755. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99.

- Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, Bonham CA, Morgenthau AS, Patterson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American thoracic society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):e26–e51. doi:10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST.

- Jabs DA, Nussenblatt RB, Rosenbaum JT, Standardization of Uveitis NomenclatureWorking G. Standardization of uveitis nomenclature for reporting clinical data. Results of the First International Workshop. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(3):509–516. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.057.

- Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature Working G. Classification Criteria for sarcoidosis-associated uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;228:220–230. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.047.

- Mochizuki M, Smith JR, Takase H, Kaburaki T, Acharya NR, Rao NA, et al. Revised criteria of International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis (IWOS) for the diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019;103(10):1418–1422. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-313356.

- Dietmaier WWC, Sivasubramanian N. LightCycler PCR For the Polymorphisms -308 and -238 in the TNF Alpha Gene And for the TNFB1/B2 Polymorphisms in the LT Alpha Gene. RapidCycle Real-Time PCR – Methods and Applications Genetics and Oncology. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002: 95–105.

- Voorter CE, Rozemuller EH, de Bruyn-Geraets D, van der Zwan AW, Tilanus MG, van den Berg-Loonen EM. Comparison of DRB sequence-based typing using different strategies. Tissue Antigens. 1997;49(5):471–476. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.1997.tb02781.x.

- Hwang DK, Sheu SJ. An update on the diagnosis and management of ocular sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2020;31(6):521–531. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000704.

- Seve P, Jamilloux Y, Tilikete C, Gerfaud-Valentin M, Kodjikian L, El Jammal T. Ocular Sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41(5):673–688. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1710536.

- Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rossman MD, Yeager H Jr., Bresnitz EA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 Pt 1):1885–1889. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046.

- Judson MA, Boan AD, Lackland DT. The clinical course of sarcoidosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment in a large white and black cohort in the United States. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2012;29(2):119–127.

- Chung YM, Lin YC, Liu YT, Chang SC, Liu HN, Hsu WH. Uveitis with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis in Chinese–a study of 60 patients in a uveitis clinic over a period of 20 years. J Chin Med Assoc. 2007;70(11):492–496. doi:10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70047-9.

- Ungprasert P, Crowson CS, Matteson EL. Influence of gender on epidemiology and clinical manifestations of sarcoidosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study 1976-2013. Lung. 2017;195(1):87–91. doi:10.1007/s00408-016-9952-6.

- Wilsher ML, Young LM, Hopkins R, Cornere M. Characteristics of sarcoidosis in Maori and Pacific Islanders. Respirology. 2017;22(2):360–363. doi:10.1111/resp.12917.

- Wu JJ, Schiff KR. Sarcoidosis. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(2):312–322.

- Sen HN, Davis J, Ucar D, Fox A, Chan CC, Goldstein DA. Gender disparities in ocular inflammatory disorders. Curr Eye Res. 2015;40(2):146–161. doi:10.3109/02713683.2014.932388.

- Tsirouki T, Dastiridou A, Symeonidis C, Tounakaki O, Brazitikou I, Kalogeropoulos C, et al. A focus on the epidemiology of uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(1):2–16. doi:10.1080/09273948.2016.1196713.

- Takase H. Characteristics and management of ocular sarcoidosis. Immunol Med. 2022;45(1):12–21. doi:10.1080/25785826.2021.1940740.

- Lee JH, Han YE, Yang J, Kim HC, Lee J. Clinical manifestations and associated factors of uveitis in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: a case control study. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22380. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-49894-5.

- Niederer RL, Sharief L, Tomkins-Netzer O, Lightman SL. Uveitis in sarcoidosis - clinical features and comparison with other non-infectious uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2023;31(2):367–373. doi:10.1080/09273948.2022.2032189.

- Perez-Alvarez R, Brito-Zeron P, Kostov B, Feijoo-Masso C, Fraile G, Gomez-de-la-Torre R, et al. Systemic phenotype of sarcoidosis associated with radiological stages. Analysis of 1230 patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2019;69:77–85. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2019.08.025.

- Allegri P, Olivari S, Rissotto F, Rissotto R. Sarcoid uveitis: an intriguing challenger. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58(7). doi:10.3390/medicina58070898.

- Zur Bonsen LS, Pohlmann D, Rubsam A, Pleyer U. Findings and graduation of sarcoidosis-related uveitis: a single-center study. Cells. 2021;11(1):89. doi:10.3390/cells11010089.

- Sungur G, Hazirolan D, Bilgin G. Pattern of ocular findings in patients with biopsy-proven sarcoidosis in Turkey. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(6):455–461. doi:10.3109/09273948.2013.775311.

- Reid G, Williams M, Compton M, Silvestri G, McAvoy C. Ocular sarcoidosis prevalence and clinical features in the Northern Ireland population. Eye (Lond). 2022;36(10):1918–1923. doi:10.1038/s41433-021-01770-0.

- Erckens RJ, Mostard RL, Wijnen PA, Schouten JS, Drent M. Adalimumab successful in sarcoidosis patients with refractory chronic non-infectious uveitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(5):713–720. doi:10.1007/s00417-011-1844-0.

- Choi SY, Lee JH, Won JY, Shin JA, Park YH. Ocular manifestations of biopsy-proven pulmonary sarcoidosis in Korea. J Ophthalmol. 2018;2018:9308414. doi:10.1155/2018/9308414.

- Rasmussen A, Dawkins BA, Li C, Pezant N, Levin AM, Rybicki BA, et al. Multiple correspondence analysis and HLA-associations of organ involvement in a large cohort of African-American and European-American patients with sarcoidosis. Lung. 2023;201(3):297–302. doi:10.1007/s00408-023-00626-6.

- Garman L, Pezant N, Pastori A, Savoy KA, Li C, Levin AM, et al. Genome-wide association study of ocular sarcoidosis confirms HLA associations and implicates barrier function and autoimmunity in African Americans. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29(2):244–249. doi:10.1080/09273948.2019.1705985.

- Wijnen PA, Cremers JP, Nelemans PJ, Erckens RJ, Hoitsma E, Jansen TL, et al. Association of the TNF-alpha G-308A polymorphism with TNF-inhibitor response in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1730–1739. doi:10.1183/09031936.00169413.

- Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, Rosenstiel P, Albrecht M, Stenzel A, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37(4):357–364. doi:10.1038/ng1519.

- Coudurier M, Freymond N, Aissaoui S, Calender A, Pacheco Y, Devouassoux G. Homozygous variant rs2076530 of BTNL2 and familial sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2009;26(2):162–166.

- Li Y, Wollnik B, Pabst S, Lennarz M, Rohmann E, Gillissen A, et al. BTNL2 gene variant and sarcoidosis. Thorax. 2006;61(3):273–274. doi:10.1136/thx.2005.056564.

- Suzuki H, Ota M, Meguro A, Katsuyama Y, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, et al. Genetic characterization and susceptibility for sarcoidosis in Japanese patients: risk factors of BTNL2 gene polymorphisms and HLA class II alleles. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(11):7109–7115. doi:10.1167/iovs.12-10491.

- Heiligenhaus A, Wefelmeyer D, Wefelmeyer E, Rosel M, Schrenk M. The eye as a common site for the early clinical manifestation of sarcoidosis. Ophthalmic Res. 2011;46(1):9–12. doi:10.1159/000321947.

- Dammacco R, Biswas J, Kivela TT, Zito FA, Leone P, Mavilio A, et al. Ocular sarcoidosis: clinical experience and recent pathogenetic and therapeutic advancements. Int Ophthalmol. 2020;40(12):3453–3467. doi:10.1007/s10792-020-01531-0.