ABSTRACT

COVID-19 extended through 2020 with impact on all hospital services. The purpose of this study was to determine the extent of orthoptic service provision during the initial recovery period from July to September 2020 in the UK, Ireland and Channel Islands. We conducted a prospective survey-based cross-sectional study using an online survey aiming for coverage of orthoptic departments across the UK, Ireland and Channel Islands. The survey sought to gather data on orthoptic practice during the COVID-19 pandemic period between the first and second waves in the UK. Questions included within the survey asked about the impact on services paused or reduced during the pandemic, the reinstatement of services, backlog of appointments, changes to arrangement and conduct of appointments, changes to working practice, impact to lives of orthoptists, and access by orthoptists to professional support and guidelines. We circulated the online survey through the British and Irish Orthoptic Society that reaches over 95% of UK and Irish orthoptic services and through social media and orthoptic research networks. This survey was open from July 1st to September 30th 2020 and achieved a response rate from orthoptic departments of 85%. A high rate (92%) of teleconsultations continued with 50% of departments using a proforma to guide the teleconsultation and with added use of risk assessment for patient appointments. To enable reopening of clinics, multiple changes were made for patient and staff flow through clinic areas. Reduced clinical capacity was confirmed by 76.5% of departments. Appointments averaged 15–20 minutes and there was routine use of PPE and cleaning and adoption of staggered appointments with added evening/weekend clinics. There was increased use of information resources/leaflets for patients and dependence on professional and health care guidance documents. The average backlog for patient appointments had increased to 26 weeks. The initial UK and Irish recovery phase in summer 2020 allowed a glimpse at adjustments needed to reopen orthoptic clinics for in-person appointments. Teleconsultation remained in frequent use but with greater risk assessment and triage to identify those requiring in-person appointments.

Introduction

COVID-19 continues to dominate and have impact on hospital services more than one year on from its emergence in the UK and Republic of Ireland. After the first lockdown on March 23rd 2020, there was a short recovery period over summer 2020 before rising infection rates led to renewed restrictions from September 14th and a second lockdown from November 5th with further restrictions from January 6th 2021. Subsequently, relaxation measures were further introduced in March 2021. COVID-19 had a significant impact on the delivery of eye care services in the UK and internationally,Citation1–3 particularly due to potentially higher risks of transmission through contact with ocular secretions such as tears and ocular discharge.Citation4,Citation5

In the UK, there is an extensive clinical service provided by orthoptists within the eye care system, primarily sited not only in hospital services (National Health Service NHS Trusts or Health Boards) but also in community care settings.Citation6 UK orthoptists assess and manage a wide range of conditions affecting vision and, although their patient population typically includes children, there is a considerable adult population served by orthoptists also. Specialist UK orthoptic services include child vision screening, brain injury and neurorehabilitation, and services for falls prevention, glaucoma and medical retina monitoring, specialist educational needs, and visual processing difficulties and low vision.Citation6 In 2020, we reported the impact on orthoptic services and experiences of orthoptists during the first lockdown period in a survey undertaken during the month of April 2020.Citation7 Key changes to practice were rapidly implemented including remote patient consultations, access to appropriate, and accurate use of personal protective equipment (PPE), along with reported issues related to IT access, appropriate PPE, and changing national guidance.

The ophthalmic literature has focused on ophthalmic consequences of COVID-19 infection, reporting of telemedicine, and the potential for ocular transmission of COVID-19.Citation5,Citation8–10 There has been a paucity of information regarding the emergence from lockdown and how eye care can be delivered during the recovery process with consideration to longer term impact on eye care services. The purpose of our study, therefore, was to conduct a follow-on survey of orthoptic practice in the UK during the ensuing, but temporary, recovery phase in summer 2020 after the first lockdown, in order to consider reinstatement processes for clinical services, continued to have impacts on provision of eye care services and adoption of new practices in delivery of care.

Methods

A prospective cross-sectional survey was undertaken across orthoptic departments registered with the British and Irish Orthoptic Society (BIOS), covering the UK, Republic of Ireland, and Channel Islands. The survey was approved by the University of Liverpool Research Ethics Committee (Ref. 7637). Recorded informed consent was sought. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. The first page of the survey contained information thatwould be standardly found in a participant information sheet, followed by four statements that acted as a consent form. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Initial development and pilot of survey questions took place with collaboration between the University of Liverpool and clinical orthoptic colleagues working in hospitals within the North West of England. Questions addressed the impact on services paused or reduced during the pandemic; the reinstatement of services, backlog of appointments, changes to arrangement; and conduct of appointments, changes to working practice, impact on lives of orthoptists, and access by orthoptists to professional support and guidelines (supplementary Table 1).

The survey was administered using Qualtrics softwareCitation11 and was circulated through BIOS with e-mail of the survey link to all registered heads/leads of orthoptic services (total of 175 organizations e.g. Trusts and Health Boards). The survey opened on 1st July 2020 and closed on 30th September 2020. Orthoptists were asked to respond to the survey on the basis of their department activity at the time of their response during the July-September period. Regular updates and reminders on the survey completion rate were posted through the BIOS Leads of Orthoptic Practice (LOOP) online forum along with e-mail requests to heads/leads as a reminder for survey completion. While the survey remained open, frequent updates on survey completion rates were posted using social media platforms, e.g. Twitter.

Analysis of survey results was primarily descriptive. Survey results were exported from Qualtrics software. SPSS softwareCitation12 was used for descriptive statistical analysis of the data. Open text survey responses were uploaded into NVivo softwareCitation13 for qualitative compilation of orthoptic comments. Open text responses were coded by sentence. A thematic approach to analysis of this qualitative data was adopted. Each open text question was reviewed separately. Codes were grouped for similar content and a narrative summary produced for each survey question that generated open text responses.

Results

Responses and completion rate

Responses were received from 149 hospital Trusts or Health Boards with each representing between 1 and 7 orthoptic departments across hospitals covered by the overarching Trust or Health Board. Responses from one Trust orthoptic department accounted for 71 (47.3%), two departments under one Trust/Health Board (30, 20%), three departments under one Trust/Health Board (33, 22%), and just one Trust covering seven departments (0.7%). If more than one orthoptist from the same department/hospital responded to the survey, these responses were combined to provide one department overview.

Trusts/Health Boards were from England (114, 76%), Ireland (15, 10%), Scotland (10, 6.7%), Wales (7, 4.7%), and Northern Ireland (3, 2%). The majority of surveys were completed on the same day of registration for the survey (143, 95.3%) with the remaining surveys completed within 1–6 days of survey registration.

The survey was fully completed by most respondents (119, 79.3%) with the remainder being partially completed with between 7 and 99% of questions answered. A completion rate of above 50% was achieved by 129 departments (86%).

The person completing the survey on behalf of their Trust was not always the same person who completed the first survey earlier in 2020. Some respondents were unaware if the first survey had been completed for their Trust (22, 14.7%) or not sure who had responded for the first survey (49, 32.7%).

Consultations with patients during the pandemic

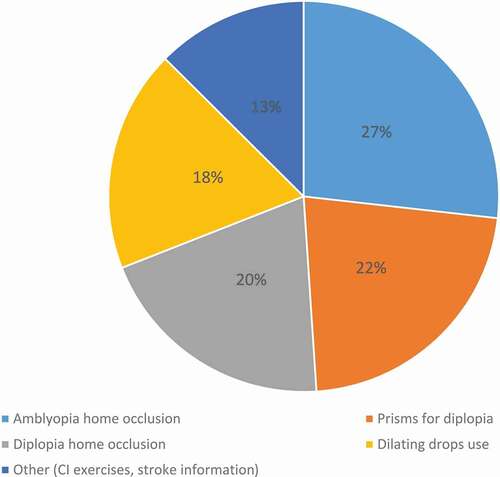

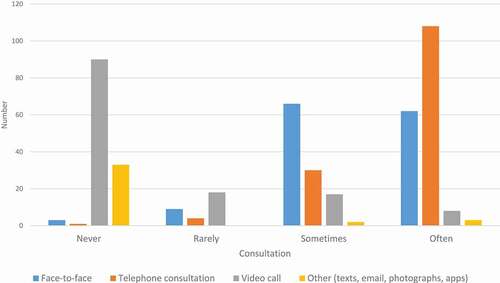

Contact with patients was still largely done by telephone consultation rather than face-to-face hospital appointments () and 51% (n = 76) of respondents reported that their clinic had implemented a proforma for teleconsultations.

Figure 1. Mode of consultation.

Over half (53%, n = 79) of respondents reported that additional information was discussed during appointments such as locations and use of foodbanks, domestic violence, general health and lifestyle, smoking cessation, COVID-19 restrictions and testing, shielding, mental health and well-being support, safeguarding, and keeping safe and eye services support.

The departments that reported implementing a proforma for use during teleconsultations, described a variety of formats of proforma including checklists and flow charts, with some being specific for different groups of patients, i.e. pediatric and adult and clinic specific. The origins of the proforma’s differed; some were based on existing in-person consultation documentation, and parts were sourced from the professional body (BIOS). Departments reported sharing documentation with other departments. The purpose of the proforma contents varied widely; some included elements of a routine clinical consultation, e.g. patient or parental concerns. Others described recording historical clinical results from the medical records, e.g. visual acuity at the previous visit and current/previous treatment. Proformas were also used as prompts for the clinician, including checking if the environment was suitable for the consultation to go ahead, Make Every Contact Count (MECC) questions (a Health Education England public health initiative to use clinician/patient contacts as opportunities to encourage behavior changes that promote positive effects on patient health and wellbeing), COVID-related questions, and explanation of how clinics will restart. They also took the form of clinical decision aids advising the clinician what treatment could be started, continued, or required stopping under the current situation. It was reported that these tools evolved as time passed and more consultations were completed.

Risk assessment was introduced when assessing patients for appointments. This was often done on an individual basis using a combination of the Royal College of Ophthalmology guidelines (), the Moorfields Risk Assessment Tool, or an adaptation, and clinical judgment, in conjunction with a review of the patient’s medical records and in some cases a telephone consultation.

Table 1. Classification of urgent or high-risk cases for face-to-face appointments

While there were reports of no specific problems with teleconsultations, others reported general IT issues, e.g. communication and phone access for the patient. It was reported that the issue of getting in touch with patients/parents worsened as restrictions eased in the summer. Once a call was answered, there were other issues reported such as poor signal and communication difficulties due to poor hearing or a language barrier.

There were concerns raised about the risk of conducting teleconsultations and relying on symptom response with patients who have conditions where a change in the condition is often not symptomatic, e.g. pituitary visual field loss.

Many departments reported no specific issues with home management of eye conditions or none that were apparent when completing the questionnaire. A commonly reported issue was related to the lack of ability to assess the patients and lack of home vision testing; therefore, the clinician was without up-to-date clinical information, making treatment decisions difficult.

Some decisions were taken on a blanket basis (i.e. same decision for every patient with a specific diagnosis), which was reported as an issue; the examples given included stopping atropine and moving to either no treatment or conventional occlusion and reducing conventional occlusion to a maintenance dose until an in-person appointment could be arranged.

It was reported as difficult to assess compliance without regular checkups:

“poorer compliance with patients who are patching as we are not seeing them as often and the parents aren’t seeing the benefit of the patching”

Compliance was mentioned especially in relation to the lockdown period.

“no routine, their children are not wanting to wear their glasses”

“Most parents use school hours to carry out occlusion - children respond better to teacher!”

One department gave only short supplies of patches to encourage patients to keep in touch with the department. Other departments found that parents were not contacting the department when they ran out of patches or when glasses were lost or broken. Departments reported difficulty in accessing optometrists to replace broken glasses (note: children are usually refracted within the hospital system but take their prescription to an outside optometry practice to obtain glasses). There was also the assumption of parents that all optometrists were closed, resulting in children being without glasses for long periods of time.

The only issue reported for management in relation to adult patients was prism fitting. It was reported that prism fitting was attempted at home, typically for replacement prisms but occasionally for new prism fitting, but did result in errors and the patient having to subsequently attend clinic. In cases where prism fitting was not possible, clinicians resorted to occlusion to manage diplopia.

Another issue reported was communication and explanation of management plans over the telephone. This was seen as potentially problematic without the ability of demonstration:

“understanding can be compromised when not face to face”

Ten respondents reported potential issues with liability or altered practice, for example, related to lack of insurance for video call visual assessments and app use for visual testing.

There was an increase in supply of leaflets for home information (). There was an increase in discharge of patients who would have been automatically reviewed. Such discharge was reported by 26.8% (n = 40) for children with no obvious ocular issue but with positive family history and by 30.9% for routine follow-ups of adults wearing prisms. Other discharge groups included annual review appointments, those who could be discharged to local optometrists (myopes/general glasses wear), older children, stable postoperative reviews, and those already due for discharge. Discharge was predominantly not only to local optometry services (65.1%, n = 97) but also to school screening, community care, GP care, and community rehabilitation.

Alterations to appointments

Questions were posed about the altered conduct of appointments. For individual appointments, time for doffing/donning PPE and cleaning between patients was reported as a range from 1 to 20 minutes, but generally a range of 5 to 20 minutes (one outlier of 1 minute) with a median of 10 minutes (mean 13.7) per appointment. The time allocated for in-person appointments ranged from 10–60 minutes with a minimum of 10 minutes for the appointment and up to 60 minutes for the added PPE and cleaning (mean 29.9 minutes). Clinics ran at reduced capacity from normal circumstances. This was originally up to 90% reduction in capacity during the early stages of the pandemic (March to June 2020) and reduced to 50% and below (mean 38%) in the stage covered by the follow-up survey (July to September 2020). Difficulty with running orthoptic clinics in community settings was reported by 49% (n = 73). There were reports of departments being unable to access their community settings or having dates on which they will be reopen. One department expressed the importance of community clinics in light of limited numbers being seen within hospitals:

“This is required even more now … we cannot see as many patients on the hospital site and need community settings.”

Difficulty with accessing community settings was caused by various situations. One issue was simply that buildings had not yet been reopened. Another issue reported was that other departments were now using the room previously used by orthoptics, which included other department being relocated or a new use for COVID assessment. Departments also reported that shared buildings were causing issues, with cases of other services preventing access for patients, and some building being owned by another organization with different policies in use, which prevented clinics from restarting.

Departments also reported being unable to access other locations in the community where orthoptists carry out assessments, such as special schools, schools, and pre-schools. If access to buildings was possible, other issues reported included difficulties with infection control including curtains and blinds having to be removed and accessing PPE across a wide number of sites including ensuring that patients had access to masks at building entrances.

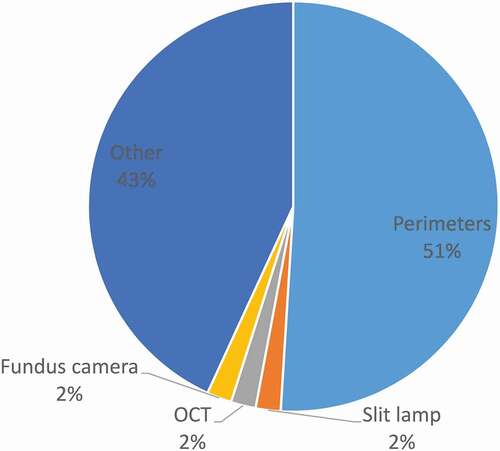

Equipment use

Some respondents (26.8%, n = 40) reported that they were unable to use certain equipment during the pandemic (). Many departments reported of following the manufacturer’s guidance in relation to cleaning. Wipes were used for the outside of perimeters and other equipment, with 70% alcohol spray being used for perimeter bowls. Soap and water were reported to be used for equipment, which would not tolerate regular use of wipes such as stereo tests and prisms.

Guidance and training

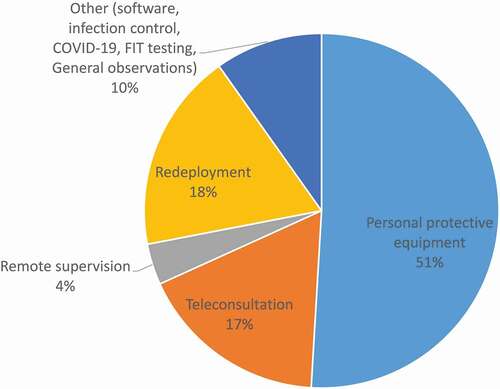

Just over half of respondents (52.3%, n = 78) reported the use of guidance documents including those from the British and Irish Orthoptic Society (BIOS), Royal College of Ophthalmology, and NHS Trusts and manufacturer (e.g. Zeiss, Haag Streit, Topcon). Most guidance (85.2%, n = 127) was related to PPE. Specific training was also received during the pandemic ().

Staff uniforms

Wearing a uniform pre-COVID-19 was reported by 21.5% (n = 32), and an additional 8.1% (n = 12) adopted a uniform during the pandemic (typically scrubs). Most had access to changing facilities or did not need these. However, one quarter did not have access to required changing facilities. A small number (6.7%, n = 10) reported having to make or supply their own PPE (specifically masks and visors).

Many departments reported no general issues with uniforms. However, there were reports from departments of limited supplies of scrubs and uniforms, with delays of delivery. This issue resorted to individuals in departments purchasing their own scrubs or departments using donated homemade scrubs. Others reported requesting to wear scrubs, but this request was denied by the Trust. Departments also reported recently having moved away from using uniforms, due to the patient groups that they worked with or confusion between different professional groups.

Department changes

There was a wide variance on department changes made to accommodate social distancing. This included having less staff in clinics (49.7%, n = 74), staff working from home (55%, n = 82), and rearranged clinic space (66.4%, n = 99). Ten respondents (6.7%) reported no changes to departments, and 15 (10.1%) were unable to follow recommendations because corridors were not wide enough, needed to be within 2 m distance for ocular motility assessments, access only to small offices, limited space, and too many patients within a small area. Other department changes included use of shields (typically clear Perspex screens) in open plan areas, extended working days, staggered appointment times, fewer patients allowed in clinic at the same time, rota of staff, and additional room access for assessments. The majority (82.6%, n = 123) reported a change to the patient numbers accessing their departments.

Many reported changes to how patients move through and around their departments. Departments reported reducing the number of patients booked into clinics, therefore to reduce the numbers in clinic at any one time. Increased clinic hours were reported as a way of increasing the number of patients seen.

Changes in flow around departments were reported including one-way systems, different doors for entrance and exit, and keeping left on corridors. It was reported that dividing doors were installed to create separation between green (COVID-free) and yellow areas (possible COVID), creating different areas for pediatric and adult patients.

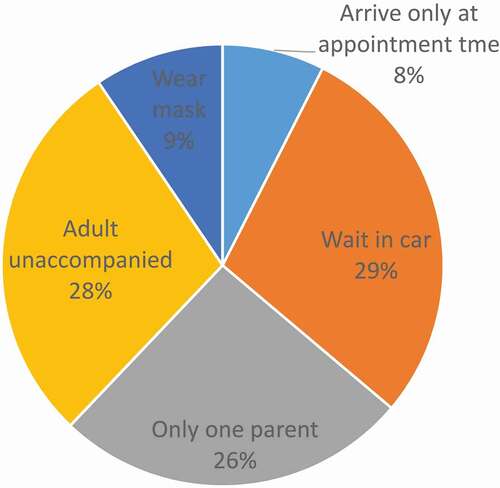

Other measures were reported to aid social distancing and prevent patients having to wait while in departments; e.g. staggered appointment times, limited chairs were available within waiting rooms, patients were asked to wait in their cars and phoned to come straight to clinic rooms, and patient no longer booked their next appointment at reception, waiting outside while dilating.

The way in which the flow of the clinical consultation was reported to have changed to reduce wait time and movement around the department is that, e.g., dilation being done by the orthoptist rather than pediatric ophthalmic nurse and patients remaining in one clinic room and the clinicians/equipment moving. Departments also reported reducing the number of assessment stations in clinic rooms. Different actions have been taken with regard to joint clinics; some departments reported canceling all joint clinics to reduce the time in waiting rooms, while other department increased the number of joint appointments to reduce the number of hospital visits required.

Staff support

Requests for personal support (e.g. mental health concerns, childcare support, and redeployment) were made by respondents in 40.3% (n = 60) of departments with support received from BIOS psychology first aiders, Trust support, general NHS support, additional one-to-ones, mental health, childcare, work from home, occupational health, counseling, GP, apps (e.g. Headspace), mindfulness, and redeployment.

Redeployment

Thirty departments reported redeployment roles for orthoptists, 84 reported no redeployment but options for this had been discussed, and 13 reported no redeployment and no discussion of this with staff. The roles reported to be covered by orthoptic redeployment included:

Assistant roles – radiology assistant, Occupational Therapy assistant, 2nd assistant in intravitreal therapy (IVT) clinics, backfill of nursing health care assistant (HCA) roles, chaperones, buddy system on late shifts for community nursing, and ward runner.

Administrative roles – canceling and rebooking appointments, triaging, filing letters, receptionist, procurement, lost to follow-up spreadsheet management, staff sickness absence phone line, telephone reporting results to trust staff, and manning relative support line.

Other hospital department roles – Human Resources, IT services, trade union support, and bereavement service.

Other roles within Ophthalmology – Triage and assessment in urgent eye clinic and preassessment in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) clinic.

COVID-related roles – Swabbing for COVID-19, PPE fit testing, donning and doffing, visor making, proning, and scrubs exchange.

Redeployment commenced at varying time points from March 20th 2020 through to July 2020 with a median start date for other roles by April 1st.

Appointment backlog

Respondents report a mean backlog and increase in waiting list times of 25.92 weeks.

Return of services

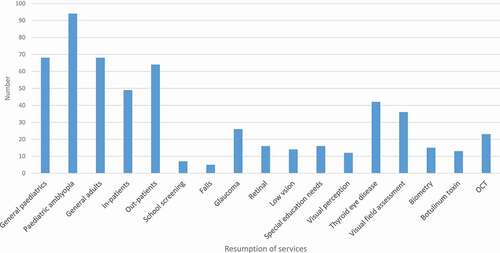

After the first lockdown in March/April 2020, there was a gradual increase in orthoptic services ().

Figure 5. Resumption of services.

A reduction in clinical capacity was confirmed by 76.5% (n = 114). To reduce the amount of face-to-face time spent with patients, departments reported using hybrid appointment, maintaining social distancing during an appointment where possible and selective testing. Departments reported using telephone consultations preappointment to collect information regarding symptoms and history and then following the appointment for any extended discussions or questions. During face-to-face appointments, staff maintained a distance greater than two meters when possible, for example, during history taking, visual acuity assessment, and prism fitting. Departments also reported using selective testing during face-to-face appointments, while stipulating this was based on clinical needs and the autonomy of the clinician.

For staggered appointments, the mean staggered interval time was 23.13 minutes. Others had sufficiently large clinical rooms to accommodate more than one patient and could also stagger arrival times. Restricted time limits for appointments were confirmed by 49.7% (n = 74) respondents. The majority (>90%) reported time limits of 15–20 minutes with a maximum allowance of 30 minutes if including a socially distanced discussion after vision testing and a maximum of 60 minutes for extended role appointments. Three quarters of respondents (n = 115) reported provision of instructions to patients prior to attending appointments ().

Figure 6. Patient instructions for attendance.

Working hours

A return to routine service hours (pre-COVID) was reported by 55% (n = 82). Different working hours were confirmed by 22.1% (n = 33). Departments reported working extended hours over fewer days (10–12 hour shifts, 9-day fortnight, and evening clinics) and weekend working.

Recovery planning

Respondents reported a variety of guidance documents used for recovery planning ().

Table 2. Recovery planning

Altered practice for future services

Departments have reported several elements of the changes required to practice during the pandemic that will be adopted going forward. The use of telephone/video consultations was mentioned by many departments with some specifying how this would be used: for advice and guidance, triage, and intermittent follow-up consultations for some patient groups.

Departments reported new patient pathways that would continue including shared care and closer collaboration with community optometry and clinics, increase of follow-up intervals, and dilation at home. A common change to patient pathways that was reported referred to improving discharge policies:

“I think we got into habit of keeping patients under our care to monitor for longer than necessary.”

Changes to working hours are planned to continue within departments including extended working days and weekend working. Other changes to how orthoptists work within departments reported to be adopted going forward included continuation of uniform wear, use of virtual meetings, working from home when doing administration tasks, and maintenance of cleaning regimes.

What did not work during COVID

Interactions with patients changed, moving to telephone or video consultation. While a lot of departments reported that they would continue to use these types of consultation moving forward for specific purposes, having this as the main method of consultation did not work. It was reported that telephone consultations were only suitable for in-between visits and for some patients and conditions, they are not appropriate. These issues are on top of issues of incorrect numbers and no answer to telephone calls.

Teams had to also change the way they worked, with reports of teams being split to enable social distancing and members of teams being redeployed. It was not always known what was going to happen and changes occurred very quickly causing anxiety. Departments reported poor communication from management and uncertainty if redeployment would happen. It was also reported that a large amount of orthoptic time was spent on administration duties due to lack of admin support, such as canceling and rescheduling appointments.

Departments reported how care for patients changed and did not work including blanket changes to appointments and management. Amblyopia treatment was stopped in many departments; there was concern reported for patients who had made good progress and would likely experience regression in their level of visual acuity. It was commonly reported that difficulty in assessing patients remotely was due to the lack of an approved method of parents/patients assessing vision at home. There was also concern reported related to keeping track of canceled patients and poor attendance caused by short notice for appointments. In order to increase the number of patients seen, departments reported lengthening the working day and evening clinics; however, it was found that these were not suitable for pediatric patients, due to poor cooperation of younger children when tired.

Discussion

The response rate for participating orthoptic departments in this survey was high at 85% and exceeded the 79% response rate from our previous survey.Citation7 Although the aim of this survey was to address the follow-on recovery phase, for those who were unaware of whether the first survey had been completed for their department, the opportunity was provided to add information related to first survey questions regarding the number of orthoptists employed per trust, the range of services provided pre-COVID-19, how services were canceled during the first lockdown period, how consultations were provided during the pandemic, and how clinical data were gathered. Where this additional information was provided, the range of responses were very similar to the first survey responses, e.g. telephone consultations remained high at 92% in the second survey, and the same apps continued to be used. However, more information was provided in this follow-on survey about use of eye images such as from video recording of eye position and movements plus photographs sent to clinicians.

Consultation with patients during the recovery phase was dominated still by teleconsultations, with the difference to the first lockdown being the introduction of a proforma by over half of the services for such consultations. The proformas provided a guide for orthoptists to ensure that a variety of aspects were covered during the consultation such as public health information about COVID-19, access to food banks and social services if required, and hospital access information, in addition to the triage required for the person’s visual symptoms and/or condition. While some public health aspects such as the MECC questions were already in place prior to COVID-19, most aspects introduced in these proformas were in response to issues related to COVID-19 circumstances and were informed by updated public health guidance and information from Trust and professional guidance. The high teleconsultation provision mirrors practice across a variety of different eye care services, with teleconsultation (telephone or video) in two thirds to three quarters of patient consultations.Citation14–16 A further option was the use of SMS text messages for outpatient attendance specific to postponement of appointments and drug refills.Citation17 One quarter of patients responded to these text messages with a high satisfaction rate (96%) among those responding.

However, such services were not without limitations. There were concerns regarding the reliability of teleconsultations and, although acceptable to get through the pandemic, about half of the surveyed ophthalmologists did not plan regular virtual consultations postpandemic.Citation16 Of those not completing a teleconsultation, this was most likely because there was no answer to the phone call.Citation14 For those completing teleconsultations, patients reported a high level of satisfaction with the service under pandemic conditions.Citation15

Notably, more than 50% of respondents reported a deviation away from the ‘usual eye care discussion toward conversations on issues such as public health, safeguarding, and access to food banks. Respondents raised concerns about risk assessment with teleconsultations and reported reliance on national guidelines.Citation18–20 This has been reported elsewhere in UK ophthalmology services. Attzs and colleagues reported the benefit of UK national ophthalmic guidelines and stressed the importance of risk assessment for patients that had been canceled or placed in review lists.Citation2 Their study reported the implementation of strict triage protocols, for example, in place of prior walk-in services for urgent care.

The continuation of high numbers of teleconsultations brought remote testing of visual function to the forefront with concerns raised regarding the reliability of patient/parent-administered testing. A number of studies have been conducted during the pandemic specific to evaluating the reliability of home testing of visual acuity using software applications. Satgunam et al. conducted a validation study of smart phone acuity measurements in adult employees and reported that age and refractive error were important considerations when extending such studies to patient populations.Citation21 In adult patients, results from smart phone eye chart app use corresponded well to results obtained with standard EDTRS acuity charts.Citation22 One UK-based orthoptic study assessed parental ability to home test their child’s acuity comparing the Peek acuity and iSight Pro apps.Citation23 Only 15 of 103 families agreed to home test with most finding it easy; however, some struggled. Thus, parental engagement and education must be addressed in future studies that evaluate home testing.

Further reviews report the use of digital technology in ophthalmology, confirming the increase in the number of studies addressing IT across screening and monitoring of ophthalmic conditions with measures of visual acuity, visual fields, and optic disc images.Citation24,Citation25 Orthoptists in our survey raised a note of caution with reliance on home testing, noting potential for liability and insurance concerns with unreliable results. This concern was not unwarranted. An ophthalmology survey in Turkey reported that almost 15% of ophthalmologists confirmed that they missed a diagnosis during remote testing.Citation26 Further concerns were raised with monitoring treatment compliance, particularly for amblyopia therapy. Many orthoptic departments took the decision to reduce treatment dose or stop occlusion as a risk avoidance measure.

During the initial recovery phase, return of services was gradual and restricted with reduced capacity and selective patient assessment. The return to greater numbers of in-person appointments during the recovery phase necessitated multiple adjustments to clinical practice with impact on the number and organization of appointments, use of equipment, access to PPE and uniform, and COVID-19 testing. This is reflected in a report by Chandra and colleagues on the ‘new normal’ beyond COVID-19 including increased use of technology, greater integration of multidisciplinary teams, reduced patient contact time, regular testing for COVID-19 infection, training of clinicians, and recognition of the psychological impact on clinicians.Citation27 Further reports provide recommendations for eye care as lockdown eases with a need for frequent updating of PPE guidance.Citation28

In order to facilitate in-person appointments, a variety of initiatives were reported from staggered appointments, adopting longer working days and providing evening and weekend clinics. Issues were reported, however, in terms of reduced equipment use and the need for guidelines on cleaning of specialist ophthalmic equipment. This is acknowledged, along with the need for appropriate PPE use, for safe use of equipment such as the slit-lamp and indirect ophthalmology.Citation2,Citation3 Safe use of ophthalmic equipment with appropriate cleaning and use of PPE stems from the risk of COVID-19 transmission. The need for suitable PPE is starkly outlined by the death of Dr Li Wenliang who first warned of COVID-19 in 2019. He contracted COVID-19 from one of his glaucoma patients. The ocular surface has been reported to act as both a reservoir and source for the transmission of COVID-19 through hand/eye contact and aerosols.Citation3–5 However, it is more likely that transmission occurs because of poor PPE allowing contraction of the virus during very close proximity with infected patients undergoing ophthalmic assessments. Clear, updated guidance was reported as essential to planning and providing clinical care with access to a variety of national professional and NHS informationCitation18–20 as has been the case for other countries.Citation3,Citation29

Initiatives such as staggered appointments and shorter appointment time slots to minimize patient contact time result in less appointments available for patients. Typically, patients were assigned 15–20-minute appointments. Shorter appointment times were driven by the necessity to factor in added time for PPE doffing/donning alongside cleaning of the clinical area and equipment between patients. Inevitably, this has further extended waiting lists in addition to those arising from appointment cancellations and postponements during the initial lockdown. Waiting lists had extended to an average of 26 weeks at the time of this survey. This echoes the reports of increasing waiting lists in other countries where, pre COVID-19, there had been a buildup of long waiting lists, which are now exacerbated by the pandemic.Citation30 The long-term impact will be felt for many years after this pandemic.

Beyond the long-term impact on clinical waiting lists for appointments, there is also the impact on the health and well-being of clinicians to consider. Forty percent of respondents in our survey reported requests for personal support, not only from a mental health perspective but also practically in relation to childcare support, altered job roles (e.g. redeployment), and work from home. These are important considerations, and mental health support, in particularly, has been flagged among ophthalmologists.Citation26

Negative aspects of COVID-19 on eye care have been highlighted by this survey, for example, limited communication during the pandemic, slow release of guidance, access to PPE, and difficulty with monitoring treatment (e.g. for amblyopia). However, from a positive perspective, orthoptists have identified a number of benefits from changed practice during the pandemic. An element of teleconsultation is likely to be adopted in the future for follow-up of certain patients (e.g. annual reviews), for some, an increase of follow-up appointments in community settings will be possible, and altered working days with evening/weekend clinics and staff rotas may aid a future gradual reduction in waiting lists. A further positive outcome reported by respondents was the increase in the discharge rate specific to certain patient groups including long-term follow-up of patients under annual review, those children with, so far, normal clinical examinations despite strong family history of strabismus, and adult patients with stable prismatic therapy. Improved collaboration with community optometry services facilitated these discharges.

Conclusions

Our high response rate of 85% allows us confidence to generalize the responses to all orthoptic departments across the UK and Ireland. Concerns are still present regarding reliability of remote testing, and although teleconsultation practice has improved and will undoubtedly continue in the long-term for certain patient groups, the need for in-person appointments remains, to ensure diagnostic accuracy and to monitor active treatment.

There are considerable negative impacts on eye health care from the COVID-19 pandemic, not least the increased waiting lists that continue to grow from subsequently lockdown periods in late 2020/early 2021. However, lessons from this initial recovery phase include improved proformas for risk assessment and patient assessments, improved patient ‘flow’ through clinics when attending in-person appointments, and improved guidance for clinicians.

The impact from COVID-19 goes beyond the impact on patient health and provision of eye care services. The impact on clinicians in both their work and personal lives is clearly visible. Despite the negatives, orthoptists have identified many positive outcomes from the pandemic to inform future changes and improvements to clinical practice, showing true ‘vision’ in their visual occupation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Each author (FR, LH and CH) contributed to the design, conduct, analysis, and write-up of this paper.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Institute ethical approval was obtained for this survey (Ref. 7637). The first page of the survey served as a consent form for participants. Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Transparency statement

The lead author confirms that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (161.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We acknowledge all orthoptists taking part in this survey and thank BIOS for their assistance in circulating the survey.

Funding

This research was part funded by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration North West Coast (NIHR ARC NWC). The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

References

- Wang H, Elsheikh M, and Gilmour K, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on eye cancer care in United Kingdom. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:1357–1360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-021-01274-4.

- Attzs MS, and Lakhani BK. COVID-19 and its effect on the provision of ophthalmic care in the United Kingdom. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(7):e14052. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14052.

- Vagge A, Desideri LF, Lester M, et al. Management of pediatric ophthalmology patients during the COVID-19 outbreak: experience from an Italian tertiary eye center. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2020;47:213–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/01913913-20200513-01.

- Qu JY, Xie HT, Zhang MC. Evidence of SARS-CoV-2 transmission through the ocular route. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;18:687–696. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S295283.

- Lu CW, Liu XF, Jia ZF. 2019-nCoV transmission through the ocular surface must not be ignored. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):30313–30315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30313-5.

- British and Irish Orthoptic Society. About us. www.orthoptics.org.uk/about-us/. 2021. Accessed March 16, 2021.

- Rowe F, Hepworth L, Howard C, et al. Orthoptic services in the UK and Ireland during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br Ir Orthoptic J. 2020;16(1):29–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.22599/bioj.153.

- Heimann H, Broadbent D, Cheeseman R. Digital ophthalmology in the UK – diabetic retinopathy screening and virtual glaucoma clinics in the national health service. Klinische Monatsblätter für Augenheilkunde. 2020;237(12):1400–1408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1300-7779.

- Scanzera AC, Kim SJ, and Paul Chan RV. Teleophthalmology and the digital divide: inequalities highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Eye. 2020;35:1529–1531. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-01323-x.

- Liu YA, Ko MW, Moss HE. Telemedicine for neuro-ophthalmology: challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;34:61–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0000000000000880.

- Qualtrics. Qualtrics. 2020 ed. Provo, Utah: Qualtrics; 2020.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. 25.0 ed. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; 2017.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo. 2018;12.

- Patel A, Fothergill AS, and Barnard KEC, et al. Lockdown low vision assessment: an audit of 500 telephone-based modified low vision consultations. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2021;41:295–300. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/opo.12789.

- Gerbutavicius R, Brandlhuber U, Glück S, et al. Evaluation of patient satisfaction with an ophthalmology video consultation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ophthalmologe. 2021;118(S1):89–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00347-020-01286-0.

- Capitena Young CE, Patnaik JL, and Seibold LK, et al. Attitudes and perceptions toward virtual health in eye care during coronavirus disease 2019. Telemed e-Health. 2021;27:1268–1274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2020.0424.

- Lai THT, Lee M, Au AKH, et al. The use of short message service (SMS) to reduce outpatient attendance in ophthalmic clinics during the coronavirus pandemic. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41(2):613–620. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-020-01616-w.

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Management plans for children and young people with eye and vision conditions during COVID-19. www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Paediatric-Ophthalmolgy-management-plan-during-COVID-19-090420.pdf. 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. The use of home vision testing apps as an adjunct to telemedicine in children. www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Telemedicine-for-Paediatric-Services-Rapid-Advice-FINAL-090620.pdf. 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- British and Irish Orthoptic Society. Coronavirus/COVID-19: information and guidance for orthoptic professionals about the coronavirus outbreak. www.orthoptics.org.uk/coronavirus/. 2020. Accessed March 16, 2021.

- Satgunam P, Thakur M, Sachdeva V, et al. Validation of visual acuity applications for teleophthalmology during COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69(2):385–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/ijo.IJO_2333_20.

- Tiraset N, Poonyathalang A, Padungkiatsagul T, et al. Comparison of visual acuity measurment using three methods: standard ETDRS chart, near chart and smartphone-based eye chart application. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;26:859–869. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S304272.

- Painter S, Ramm L, Wadlow L, et al. Parental home vision testing of children during COVID-19 pandemic. Br Ir Orthoptic J. 2021;17(1):13–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.22599/bioj.157.

- Sim SS, Yip MY, Wang Z, et al. Digital technology for AMD Management in the post-COVID-19 new normal. Asia-Pac J Ophthalmol. 2021;10(1):39–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/APO.0000000000000363.

- Vinod K, Sidoti PA. Glaucoma care during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2021;32(2):75–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ICU.0000000000000730.

- Erdem B, Gok M, Bostan S. The evolution of the changes in the clinical course: a multicenter survey-related impression of the ophthalmologists at the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Int Ophthalmol. 2021;41(4):1261–1269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10792-020-01681-1.

- Chandra A, Romano MR, and Ting DS, et al. Implementing the new normal in ophthalmology care beyond COVID-19. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020;31:321–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1120672120975331.

- Gegúndez-Fernández JA, Llovet-Osuna F, and Fernández-Vigo JI, et al. Recommendations for ophthalmologic practice during the easing of COVID-19 control measures. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:e973–e983. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.14752.

- American Academy of Ophthalmology, Center for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organisation. Alert: important coronavirus context for ophthalmologists. www.aao.org/headline/alert-important-coronavirus-context. 2020. Accessed June 26, 2020.

- Carneiro VLA, Andrade H, Matias L, et al. Post-COVID-19 and the Portuguese national eye care system challenge. J Optom. 2020;13(4):257–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optom.2020.05.001.