ABSTRACT

Purpose: Based on health care records and trachoma rapid assessments, trachoma was suspected to be endemic in Kaskazini A and Micheweni districts of Zanzibar. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF), and trachomatous trichiasis (TT) in each of those districts.

Methods: The survey was undertaken in Kaskazini A and Micheweni districts on Unguja and Pemba Islands, respectively. A multi-stage cluster random sampling design was applied, whereby 25 census enumeration areas (clusters) and 30 households per cluster were included. Consenting eligible participants (children aged 1–9 years and people aged 15 years and older) were examined for trachoma using the World Health Organization simplified grading system.

Results: A total of 1673 households were surveyed and 6407 participants (98.0% of those enumerated) were examined for trachoma. Examinees included a total of 2825 children aged 1–9 years and 3582 people aged 15 years and older. TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds was 2.7% (95% confidence interval, CI, 2.7–4.1%) in Kazkazini A and 11.4% (95% CI 6.6–16.5%) in Micheweni. Among people aged 15 years and older, TT prevalence was 0.01% (95% CI 0.00–0.04%) in Kazkazini A and 0.21% (95% CI 0.08–0.39%) in Micheweni.

Conclusion: Trachoma is a public health problem in Micheweni district, where implementation of all four components of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental improvement), including mass drug administration with azithromycin, is required. These findings will facilitate planning for trachoma elimination.

Background

Trachoma, a neglected tropical disease, is the most common infectious cause of blindness, responsible for visual impairment in about 2.2 million people worldwide, of whom 1.2 million are irreversibly blind.Citation1 Elimination of trachoma as a public health problem through the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvement) is a global initiative that was endorsed by the World Health Assembly in 1998.Citation2,Citation3 Prior to SAFE implementation, baseline surveys of trachoma prevalence are recommended to guide programs to deliver appropriate interventions.Citation4

In mainland Tanzania, trachoma endemicity is well established. Surveys of trachoma undertaken in 2004–2006 showed that 43 of 50 districts included had prevalences of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) ≥10%, and were thus eligible for implementation of the A, F and E components of SAFE.Citation5 The situation in Zanzibar, however, has been less clear-cut. A 1934 review of trachoma in the British Empire reported that, in Zanzibar, external eye diseases were very common, with 2–4% of school children having been incapacitated by some form of conjunctivitis.Citation6 Madana Limbert reported that 1940s immigrants from Oman into Zanzibar were not allowed access to the islands if they suffered from trachoma, and were instead sent back.Citation7 A rapid assessment undertaken in 1998 suggested that overall in Zanzibar, 15% of blindness resulted from corneal scars due to trauma, corneal perforation, vitamin A deficiency and/or trachoma; and that trachoma was more prevalent in the north-eastern part of Pemba and northern part of Unguja.Citation8 These findings were not supported by a rapid assessment of avoidable blindness (RAAB) undertaken within Zanzibar in 2007, which did not identify a single case of trachoma-related blindness.Citation9 The RAAB methodology has limitations, however, in that it is not powered to estimate the prevalence of trachomatous blindness.

More recent anecdotal evidence suggests that trachoma is endemic in parts of Zanzibar. Health care records for Micheweni district in 2009 reveal that 17 patients underwent trichiasis surgery and 48 children were diagnosed with active trachoma in that year. To confirm these routine data, a trachoma rapid assessment (TRA)Citation10 was undertaken in Micheweni district in 2010 and showed that trachoma was common: 32% of children examined had TF and 14% of adults examined had trachomatous trichiasis (TT).Citation11 In 2015, a TRA done in Kaskazini A to check if further surveys of trachoma were warranted, reported that 20% of children aged 1–9 years had TF and 10% of people aged over 15 years had TT (unpublished data). The population-based prevalence surveys reported here aimed to estimate the prevalence of TF, TT and key water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) indicators in Kaskazini A and Micheweni districts of Zanzibar.

Materials and methods

Study settings

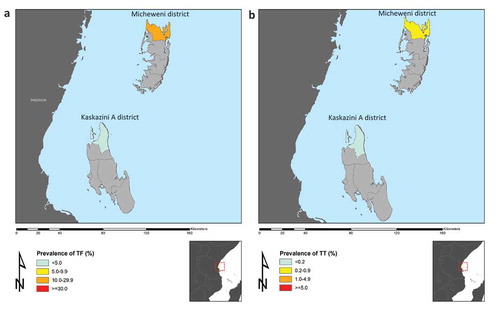

Zanzibar is a semi-autonomous part of the United Republic of Tanzania, and consists of two main islands, Unguja and Pemba. Surveys were undertaken in Kaskazini A of Unguja Island and Micheweni of Pemba Island (). TRAs were undertaken in each district to determine if a population-based prevalence survey of trachoma was warranted. Neither TRAs nor population-based prevalence surveys were conducted in the other eight districts of Zanzibar (three in Pemba and five in Unguja) since eye care records from 2009 to 2015 showed that no cases of trachoma had been reported from these districts.

Sample size estimation

To estimate the district-level prevalence of TF among children aged 1–9 years, sample size was calculated assuming an expected prevalence of 20% with an absolute precision of ±5%, 95% confidence level, 5% level of significance, a design effect of 4 and 10% non-response rate. A minimum sample size of 1082 children aged 1–9 years was required in each district. Assuming that 30% of the population was aged between 1 and 9 years, and the average household included 4.8 persons,Citation12 it was necessary to sample at least 721 households. The number of clusters per district was set at 25, therefore a total of 30 households were to be sampled per cluster, in order to reach the required sample size. Clusters were defined as census enumeration areas (EA).

The sample size for TT was calculated assuming an expected prevalence of 2%, with an absolute precision of 1%, 95% confidence level, 5% level of significance and 10% non-response rate. Based on these parameters, a total of 1657 adults aged 15 years and older in each district were required to be sampled. With 50% of the population estimated to be aged 15 years and older and an average household size of 4.8 persons,Citation12 a minimum sample of at least 663 households per district was needed in order to examine the required number of adults for TT. Therefore, a sample of at least 721 households was required to maximize the probability of examining sufficient numbers of people to adequately estimate prevalences of both TF and TT.

Sample selection

Selection of clusters

A multi-stage cluster random sampling design was used. The list of EAs in each district was obtained from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). In the first stage, 25 EAs were randomly selected, with probability proportional to population size, using computer-generated random numbers. Maps of selected EAs were then obtained from the NBS.

Selection of households and participants

A household was defined as persons living together and eating from the same pot. In the second sampling stage, 30 households were selected using the compact segment sampling method. Using the maps obtained from NBS, each EA was divided into segments of approximately 30 households. A single segment was then selected by random draw. Within the selected households, all eligible household participants (children aged 1–9 years and people aged 15 years and older) were examined.

Household interviews

Household interviews on WASH indicators were undertaken by trained interviewers using a standard questionnaire.Citation13 Heads of households were interviewed on types of water sources, distance to water source and type of sanitation facilities used by adults of the household; where the family reported using a latrine, the type was verified through observation.

Trachoma grading

Graders participating in the surveys had obtained a kappa for diagnosing TF of at least 0.7 in a formal inter-grader agreement test (based on a sample of 50 children), compared to a Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) certified grader trainer.Citation14 The eyelid, tarsal conjunctiva and cornea of each eye were examined using a 2.5× magnifying loupe and torch or sunlight, looking for signs of active trachoma and its complications. For all eyes with trichiasis, the tarsal conjunctiva was examined for trachomatous scarring (TS). TT was therefore defined as the presence of at least one eyelash touching the eyeball and TS.

Data management and analysis

Data were collected electronically using Android tablets and the LINKS system (https://gtmp.linkssystem.org/zanzibar) developed for the GTMP.Citation13,Citation14 Descriptive statistics were used to examine the sample characteristics, the prevalence of trachoma signs and proportion of households with key WASH indicators. Age- and sex-specific weights were calculated based on the 2012 population census and applied to standardize prevalence estimates by age and sex.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the survey, ethical clearance was provided by the Zanzibar Medical Research Ethics Committee and the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference 6319). Written consent (in Swahili) was signed by the head of each household selected to participate in this survey; informed verbal consent was given by each participant or their parent or guardian.

Results

Survey population characteristics

summarizes the characteristics of the population by district. A total of 6407 participants (98.0% of those enumerated) in 1673 households from 620 clusters in two districts were examined. The proportion of male participants among children 1–9 years was 49.4%, and among people aged 15 years and older was 34.1%. The mean age (standard deviation) among children aged 1–9 years was 4.8 (±2.5) years, and people aged 15 years and older was 35.7 (±16.8) years.

Table 1. Characteristics of survey population by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zanzibar, 2015.

Prevalence of trachoma signs

The prevalence of trachoma signs is shown in and . A total of 2825 children aged 1–9 years were examined for TF, and 3582 people aged 15 years and older were examined for TT. Prevalence of TF was 2.7% (95% confidence interval, CI, 2.7–4.1%) in Kazkazini A, and 11.4% (95% CI 6.6–16.5%) in Micheweni. Among people aged 15 years and older, prevalence of TT was 0.01% (95% CI 0.00–0.04%) in Kazkazini A, and 0.21% (95% CI 0.08–0.39%) in Micheweni. The prevalence of all trichiasis (with or without TS) was 0.06% (95% CI 0.02–0.25%) in Kazkazini A and 0.49% (95% CI 0.25–0.96%) in Micheweni.

Table 2. Prevalence of trachoma signs and proportion of households with key water sanitation and hygiene indicators, by district, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Zanzibar, 2015.

Prevalence of access to water sanitation and hygiene

summarizes key indicators on access to WASH. The overall proportion of households that reported using an improved drinking water source was 69.9% in Kazkazini A and 50.2% in Micheweni. The proportion of households reporting that their drinking water source was in the household yard or within 1 km of it were 89.2% in Kazkazini A and 92.4% in Micheweni. Kaskazini A had a higher proportion of households with access to improved sanitation facilities compared to Micheweni (56.6% vs 31.4%; p < 0.001).

Discussion

To achieve trachoma elimination objectives, timely baseline surveys of trachoma in suspected endemic districts are vital for planning SAFE interventions. These surveys revealed that the TF prevalence in Micheweni district was above 10% and therefore implementation of at least three rounds of mass drug administration are needed before impact surveys are undertaken.Citation15 In addition, implementation of the F and E components of SAFE will be a priority, given the low coverage of sanitation facilities in Micheweni.

Before 2009, firm evidence of trachoma in Zanzibar had not been recorded, however, trachoma was suspected to be common in Kaskazini A and Micheweni districts.Citation8 The 2009 TRA undertaken in Micheweni provided the first reliable evidence of trachoma in Pemba Island.Citation11 It is possible that trachoma is an emerging disease in Zanzibar, but given the recorded cases of TT surgery in Micheweni and our estimated TT prevalence in adults of just over 0.2% in that district, it is also possible that trachoma has been present for many years and is now slowly disappearing. The lack of consistency between our survey findings and the 2009 TRA findings in Kaskazini A is not too surprising; people attending TRAs tend, to an extent, to be self-selected, and the TRA methodology is known to be optimally biased towards finding trachoma if it is present in a population.Citation16

The surveys reported here used methods recommended by the World Health Organization for sampling of populations and examination for trachoma. Recent evidence from Ethiopia suggests that trichiasis is frequently attributable to metaplastic or misdirected eyelashes,Citation17 not all of which are aberrant because of trachoma, therefore we defined TT as trichiasis with the presence of TS. This resulted in much lower prevalence estimates (compared to any trichiasis, with or without TS) and is probably a more precise estimate for TT. Participation among adult males posed a potential limitation. Based on the 2002 population census, we expected equal numbers of males and females to be enumerated during the surveys.Citation12 Therefore the proportion of males aged 15 years and older examined was low compared to females in the same age group. It is not clear if males were systematically missing from households for reasons external to the trachoma mapping activities, or if they declined, via purposive temporary absence, to participate. While the relative paucity of adult males is a potential source of bias and might tend to overestimate the prevalence of TT (given that TT is generally more common in women than men),Citation18 standardization of TT prevalence estimates for age and sex was intended to minimize, but does not completely eliminate, this bias.

We estimated key indicators of access to WASH, including the proportion of households with an improved drinking water source, the proportion of households with a drinking water source in the household yard or within 1 km of it, and the proportion of households with sanitation facilities. For Zanzibar, the 2010 Demographic and Health Survey reported that of surveyed households, 79.5% used an improved source of drinking water, 81.1% had a drinking water source in the yard or within 1 km distance, and 50.5% had access to an improved sanitation facility.Citation19 In our data, Micheweni had a lower proportion of households with access to improved water sources (50.2% vs 79.5%) and access to improved sanitation (31.4% vs 50.5%) than the 2010 Demographic and Health Survey overall estimates for Zanzibar.

The survey findings suggest that only Micheweni district qualifies for mass drug administration with azithromycin, in addition to specific attention to targeted trichiasis surgery and district-wide implementation of the F and E components of SAFE for trachoma elimination purposes. These findings will facilitate progress of Tanzania towards achieving elimination of trachoma by 2020.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially supported by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. The funders of this study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614–618.

- World Health Organization. Future Approaches to Trachoma Control: Report of a Global Scientific Meeting, Geneva, 17–20 June 1996. Geneva. WHO/PBL/96.56: WHO; 1997. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63413

- World Health Assembly. Global Elimination of blinding trachoma. In: 51st World Health Assembly. Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11: 1998. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/WHA51.11/en/

- Ngondi J, Reacher M, Matthews F, et al. Trachoma survey methods: a literature review. Bull World Health Organ 2009;87:143–151.

- Masesa D, Moshiro C, Masanja H, et al. Trachoma prevalence in Tanzania. EA J Ophthal 2007;13:34–38. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.coecsa.org/ojs-2.4.2/index.php/JOECSA/article/view/8

- Maccallan AF. Trachoma in The British Colonial Empire. Its relation to blindness; the existing means of relief; means of prophylaxis. Br J Ophthalmol 1934;18:625–645.

- Limbert M. Personal memories, revolutionary states and Indian Ocean migrations. In: Islam and Arabs in East Africa: a fusion of identities, networks and encounters. MIT Elec J Middle East Stud. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.artsrn.ualberta.ca/amcdouga/Hist347/autumn%202012/resources/MIT%20Journal.pdf

- Ministry of Health, Zanzibar. Zanzibar Health Sector Reform Strategic Plan II 2006/07 – 2010/11. 2006. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://tanzania.um.dk/sw/~/media/Tanzania/Documents/Health/Health-sector-reform-strategic-plan-ii-zanzibar.pdf

- Kikira S. Rapid assessment of avoidable blindness in Zanzibar (MSc thesis). 2007, London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. 2007. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.lshtm.ac.uk/library/MSc_CEH/2006-07/470023.pdf

- Négrel A, Taylor HR, West SK. Guidelines for rapid assessment for blinding trachoma. 2000. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/66842#sthash.DzEHVqrJ.dpuf

- Omar F. Rapid assessment for trachoma survey in Micheweni (North Pemba) – Zanzibar (PGD Comm Eye Health Thesis). 2010, Cape Town: University of Cape Town (RSA) Community Eye Health Institute.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), Office of Chief Government Statistician (OCGS), Zanzibar. 2012 Population and Housing Census: Population Distribution by Administrative Areas. 2013. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://ihi.eprints.org//1344/

- Solomon AW, Pavluck AL, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: training for mapping of trachoma. 2012. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/resources/global-trachoma-mapping-project-training-mapping-trachoma

- International Coalition for Trachoma Control. Preferred Practices for Zithromax® Mass Drug Administration. 2013. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://trachoma.org/sites/default/files/guidesandmanuals/ICTC_MDAToolkitEN_0.pdf

- Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev 2004;17:982–1011.

- Rajak SN, Habtamu E, Weiss HA, et al. The clinical phenotype of trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia: not all trichiasis is due to entropion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:7974–7980.

- Cromwell EA, Courtright P, King JD, et al. The excess burden of trachomatous trichiasis in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2009;103:985–992.

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) [Tanzania] and ICF Macro. Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey 2010. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: NBS and ICF Macro; 2011. Accessed December 15, 2015 from: http://www.nbs.go.tz/takwimu/references/2010TDHS.pdf

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.