ABSTRACT

Purpose: To determine the prevalence of trachoma in each of the 25 local government areas (LGAs) of Niger State, Nigeria.

Methods: A population-based cross-sectional survey was conducted in each Niger State LGA between March and April 2014, as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP). GTMP protocols were used in planning and conduct of the surveys. Using probability proportional to size, 25 clusters were selected; in each of these clusters, 25 households were enrolled for the survey. All residents aged 1 year and older were examined by GTMP-certified graders for trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and trichiasis using the World Health Organization simplified grading scheme. Additionally, we collected data on household water and sanitation facilities.

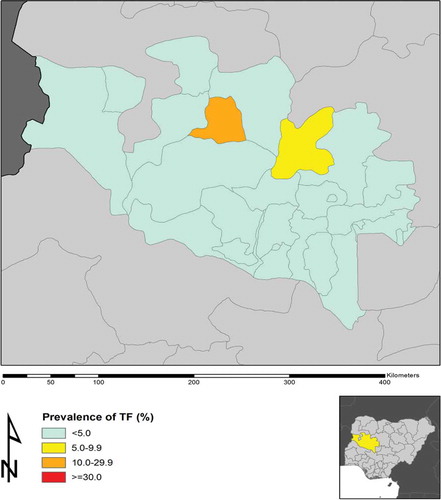

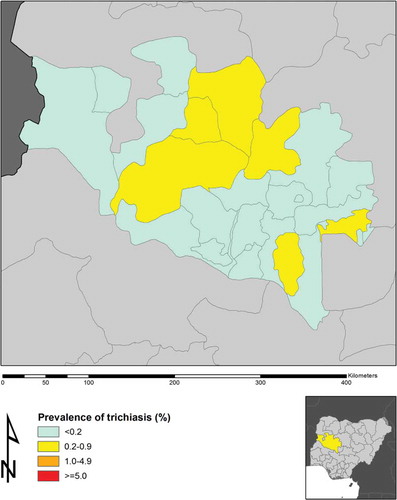

Results: Only one LGA (Kontagora) had TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds above 10%; one other LGA (Rafi) had TF prevalence between 5.0 and 9.9%. Six LGAs need trichiasis surgical services provided to achieve a prevalence of <1 case of trichiasis per 1000 total population. The proportion of households with access to improved water sources ranged from 23 to 100%, while household-level access to improved latrines ranged from 8 to 100% across the LGAs.

Conclusion: The prevalence of trachoma is relatively low in most of Niger State. There is a need for community-based trichiasis surgical services in a small number of LGAs. The trachoma elimination program could engage water and sanitation agencies to augment access to improved water and sanitation facilities, for human rights reasons. Kontagora and Rafi need community-based interventions to reduce the prevalence of active trachoma.

Introduction

Trachoma, a bacterial disease caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes A, B, Ba and C, is a leading infectious cause of blindness;Citation1 more than 200 million people worldwide are at risk.Citation2 Trachoma causes conjunctival scarring and trichiasis in its late stages, and this leads to corneal opacification and blindness. Africa is known to bear most of the global burden of trachoma.

In order to achieve the goals of the World Health Organization (WHO) Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by the year 2020 (GET2020), the WHO recommends implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery for trachomatous trichiasis, antibiotics to clear ocular C. trachomatis infection, facial cleanliness to reduce transmission of ocular C. trachomatis, environmental improvement, particularly improved access to water and sanitation) by national programs.Citation3 WHO also recommends that decisions about implementation of the SAFE strategy be made at the district level (local government areas, LGAs, in Nigeria).Citation4,Citation5 To enable planning and elimination activities in Niger State, trachoma mapping was required in all LGAs. Niger State is located in north-central Nigeria and has a population of 3,950,249 living in an estimated 729,964 regular householdsCitation6,Citation7 located in 25 LGAs. Niger State does not have an established eye care program, and trichiasis surgical services are currently facility-based except for occasional outreach undertaken during cataract surgical camps.

The aim of this study was to generate district-level baseline data on trachoma throughout Niger State, as no previous trachoma survey had been conducted there. The objectives were to estimate the LGA-level prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years and of trichiasis in individuals aged 15 years and older, and to assess household-level access to water and latrine facilities in each LGA.

Materials and methods

We conducted population-based cross-sectional surveys between March and April 2014. Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) protocols were followed in pre-survey field team training and certification, sample size calculation, data collection, and data cleaning, analysis and approval, as described in a previous publication.Citation8 Version 1 of the GTMP training system was used.Citation8

Sampling technique

We used a 3-stage sampling strategy to select the study population. Villages were used as clusters. A list of the villages in each LGA was used as the sampling frame, from which 25 clusters were selected using systematic sampling, with probability proportional to size. Within each selected cluster, we selected one ward (unguwa) using simple random sampling. A total of 25 households were then selected from each selected unguwa, using the random walk technique starting from the center of the unguwa and continuing until the desired number of households had been obtained. The random walk technique was adopted because of security concerns in northern Nigeria, as the population was already familiar with the method.Citation9–Citation11

Survey definitions

The WHO simplified grading schemeCitation12 was used to grade trachoma. All graders were ophthalmic nurses who had participated in a GTMP grader qualifying workshop and passed both the slide-based and live patient inter-grader agreement tests with kappa statistics ≥0.70. Each (GTMP-certified) grader used a 2.5× magnifying loupe to examine subjects under daylight illumination. A household was defined as people who ate from the same pot; all persons aged 1 year and older living in selected households were invited to participate. Participants were examined for TF, trachomatous inflammation – intense and trichiasis.Citation12 We also collected data on household-level access to sanitation and water facilities, through interviews and direct observation.Citation8 An “improved water source” was defined as one which, by nature of its construction and proper use, adequately protects water from outside contamination, while an “improved sanitation facility” was defined as any sanitation facility that hygienically separates human excreta from human contact.

Ethics

The ethics committees of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference 6319) and the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (reference NHREC/01/01/2007) granted approval for the study protocols. The Niger State Ministry of Health granted permission for the survey. The survey team obtained consent verbally, as the majority of the subjects were non-literate. Adults gave consent for their own participation while minors assented to examination. Consent was documented in the data collection tool (LINKSCitation8). Subjects found to have active trachoma were given two tubes of 1% tetracycline eye ointment to be applied twice daily for 6 weeks, while those with trichiasis were referred for surgery at the nearest surgical facility to the subject’s usual residence.

Data analysis

Data were cleaned and analyzed by the GTMP data manager (RW) as previously described.Citation8 R statistical software (2014; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria, Vienna)Citation13 was used for analysis including calculation of 95% confidence intervals.

Results

We examined a total of 76,941 persons; 54% were female. In the 1–9-year age group, 29,461 children were examined, of these 14,829 (50%) were female. In persons 15 years and older, we examined 40,026 persons, of whom 23,100 (58%) were female ().

Table 1. Age and sex distribution of participants, Niger State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014.

Prevalence of trachoma

The prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years ranged from 0.0% (in four LGAs) to 11.7% in Kontagora LGA; Kontagora was the only LGA with a TF prevalence of 10% or greater, with one other LGA (Rafi) having a TF prevalence between 5.0 and 9.9%. The prevalence of trichiasis in persons aged 15 years and older ranged from 0.0% (in eight LGAs) to 0.4% in Mashegu and Kontagora LGAs, as shown in , and .

Table 2. Local Government Area-level prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF) and trichiasis, Niger State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014.

Water and sanitation coverage

The proportion of households with access to improved water sources was lowest in Mashegu LGA (23%) and highest in Bida LGA (100%). Water access in the household or within a 1 km radius of it ranged from 15% in Katcha to 100% in Bida. Household-level access to latrines was lowest in Mashegu (8%) and highest in Chanchaga (100%; ).

Table 3. Household access to water and sanitation facilities, Niger State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014.

Trachoma elimination targets

All the LGAs in Niger State surpassed the elimination target for TF (prevalence <5% in 1–9-year-olds) except Kontagora (11.7%) and Rafi (7.3%) LGAs. Six LGAs (Agaie, Gurara, Kontagora, Mariga, Mashegu and Rafi) need to provide trichiasis surgery services to attain the elimination target of <1 trichiasis case per 1000 total population, which is equivalent to a prevalence of 0.2% in those aged 15 years and older.Citation5 The remaining LGAs have attained the elimination target prevalence for trichiasis. Provision of water and sanitation facilities is, however, inadequate; in several LGAs only a minority of households had access to improved sanitation or improved water sources, as shown in .

Table 4. Activities needed for elimination of trachoma as a public health problem and achievement of sustainable development goalsa in Niger State, Nigeria as of 2014.

Discussion

This study reveals that in Niger State, trachoma is generally hypoendemic, with TF prevalences <5% in all LGAs except Kontagora and Rafi. Kontagora LGA qualifies for three rounds of mass drug administration of azithromycin and implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy, before an impact survey, as recommended by WHO.Citation4 Rafi LGA had a TF prevalence of 7.3% and will require at least one round of mass drug administration and implementation of the F and E components of SAFE, followed by an impact survey.Citation14 The two LGAs are close (although not adjacent) and share similar socio-cultural characteristics; Kontagora borders Kebbi State in which there are a number of LGAs with high prevalences of active trachoma.Citation15

The presence of low trachoma endemicity despite the absence of a trachoma control program has been reported elsewhere.Citation16 This may be due to general socioeconomic development.Citation16

Only Mashegu LGA had an estimated backlog of trichiasis surgery in excess of 200 people. Kontagora LGA had an estimated 147 individuals, and Rafi had 96 individuals in need of trichiasis surgery to achieve elimination thresholds, while the other three LGAs with trichiasis prevalences above the elimination threshold each had fewer than 100 individuals requiring surgical services. Mashegu, Kontagora, Rafi, and Mariga LGAs form a block of LGAs in the geographic center of the State, are in the same senatorial and health zones, and share quite similar socio-cultural characteristics. There is a need for active case finding and community-based trichiasis surgery services in these LGAs, which should be implemented such that they could outlive the elimination campaign; it is likely that people will continue to develop incident trichiasis for years after elimination targets are achieved. A major constraint, however, is that Niger State has no trained community trichiasis surgeons; only one ophthalmologist undertakes trichiasis surgeries during occasional cataract surgical camps. The scale of intervention required is small, but there is a clear need for additional trained surgeons, and this could be achieved by training a small number of Niger’s ophthalmic nurses to undertake posterior lamellar tarsal rotation.Citation17,Citation18 Stakeholders could then help to organize active case-finding in relevant LGAs and support deployment of trained surgeons to conduct community-based surgeries.Citation19

There is a need to increase access to improved water sources, as only Bida, Paikoro, Suleja and Tafa LGAs had ≥80% of households with access to improved water. It is notable that the TF prevalence in each of these LGAs was very low. Only Bida and Chanchaga LGAs had ≥80% of households with access to improved latrine facilities. Mashegu LGA, which had the largest trichiasis burden in Niger State, had the lowest proportion of households with access to improved latrines. There is a need for provision of improved water and sanitation facilities across the state, as part of efforts towards achieving the United Nations sustainable development goals;Citation20 water, sanitation and hygiene are human rights required for more than just trachoma elimination.

There are some limitations to our data. First, although trachoma graders were required to pass the GTMP inter-grader agreement test, clinical grading has inherent inter-grader variance and drift, not apparent on kappas calculated in standardized training exercises; consistency in grading could have waned over time in (mostly) independent practice. We tried to prevent this through regular, in-service, supportive supervision, but cannot exclude its occurrence, and there is no practical way to return to check the validity of a meaningful sample of graders. Second, given the number of GTMP surveys being undertaken in a relatively short period of time, it is important to acknowledge that occasional districts with high prevalence may not necessarily represent hotspots; they may represent lag with the prevalence of TF trailing after a falling prevalence of ocular C. trachomatis, or they may just be statistical anomalies that would disappear with another survey. Third, our teams did not examine for conjunctival scarring in persons found to have trichiasis; this would have provided a more accurate estimate for determining the number of surgeries the trachoma program needs to perform to achieve trachoma elimination thresholds. An appreciation that this might be important emerged only in 2015, well after this series of surveys was completed.Citation21

In conclusion, there is less trachoma in Niger State than in some other parts of Nigeria. The trachoma control program could alert water and sanitation agencies to the need for better access to improved water and sanitation facilities in the state, to help improve human health and standards of living. Some targeted implementation of various components of the SAFE strategy should enable Niger to attain the GET2020 trachoma elimination targets.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:614–618.

- World Health Organization. WHO Alliance for the Global Elimination of Blinding Trachoma by the year 2020: progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2014;89(39):421–428.

- World Health Organization. Future approaches to trachoma control: report of a global scientific meeting, Geneva, 17–20 June 1996. Geneva: WHO Press, 1997.

- Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: WHO Press, 2006.

- World Health Organization. Report of the 2nd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma: Geneva, 25–27 August, 2003. Geneva: WHO Press, 2003.

- National Population Commission. 2006 National and state population and housing tables priority table I. Abuja. Nigeria: Author, 2010: 1–347.

- National Population Commission. 2006 housing characteristics and amenities tables – priority tables (LGA) volume II. Abuja, Nigeria: Author.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck AL, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Kano state, Nigeria: results of 44 local government area-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1265657

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Katsina state, Nigeria: results of 34 district-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23(S1):55–62.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Bauchi state, Nigeria: results of 20 local government area-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23(S1):39–45.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:477–483.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2014, ISBN 3-900051-07-0. (http://www.R-project.org)

- World Health Organization. Technical consultation on trachoma surveillance: meeting report. September 11−12, 2014, Task Force for Global Health, Decatur, GA, USA. Geneva: WHO Press, 2014.

- Muhammad N, Mohammed A, Isiyaku S, et al. Mapping trachoma in 25 local government areas of Sokoto and Kebbi states, northwestern Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol 2014;98:432–437.

- Dolin PJ, Faal H, Johnson GJ, et al. Reduction of trachoma in a sub-Saharan village in absence of a disease control programme. Lancet 1997;349(9064):1511–1512.

- Habtamu E, Wondie T, Aweke S, et al. Posterior versus bilamellar tarsal rotation surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Global Health 2016;4:e175–184.

- Solomon AW. Optimising the management of trachomatous trichiasis. Lancet Global Health 2016;4:e140–141.

- The International Coalition for Trachoma Control (ICTC) Organizing trichiasis surgical outreach, April 2015.

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September, 2015 (A/70 L.1) . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. New York: United Nations.

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachomatous Trichiasis, November 4–6, 2015, Cape Town, South Africa. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.