ABSTRACT

Aims: We sought to evaluate trachoma prevalence in all suspected-endemic areas of Benin.

Methods: We conducted population-based surveys covering 26 districts grouped into 11 evaluation units (EUs), using a two-stage, systematic and random, cluster sampling design powered at EU level. In each EU, 23 villages were systematically selected with population proportional to size; 30 households were selected from each village using compact segment sampling. In selected households, we examined all consenting residents aged one year or above for trichiasis, trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF), and trachomatous inflammation – intense. We calculated the EU-level backlog of trichiasis and delineated the ophthalmic workforce in each EU using local interviews and telephone surveys.

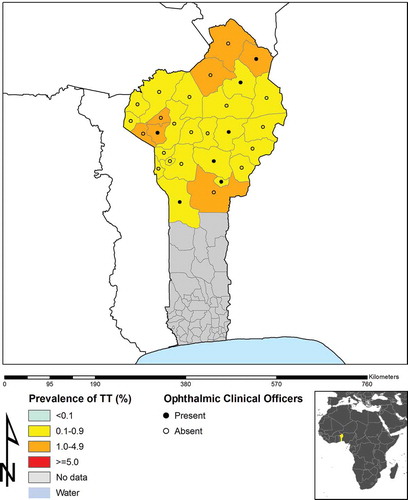

Results: At EU-level, the TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 1.9 to 24.0%, with four EUs (incorporating eight districts) demonstrating prevalences ≥5%. The prevalence of trichiasis in adults aged 15+ years ranged from 0.1 to 1.9%. In nine EUs (incorporating 19 districts), the trichiasis prevalence in adults was ≥0.2%. An estimated 11,457 people have trichiasis in an area served by eight ophthalmic clinical officers.

Conclusion: In northern Benin, over 8000 people need surgery or other interventions for trichiasis to reach the trichiasis elimination threshold prevalence in each EU, and just over one million people need a combination of antibiotics, facial cleanliness and environmental improvement for the purposes of trachoma’s elimination as a public health problem. The current distribution of ophthalmic clinical officers does not match surgical needs.

Introduction

The year 2020 is the target date for the global elimination of trachoma as a public health problem.Citation1 As the first step to achieving this goal, mapping is needed to assess the endemicity of trachoma and determine the need for interventions.Citation2

In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that 21 million people had active (inflammatory) trachoma (trachomatous inflammation – follicular, TF and/or trachomatous inflammation – intense, TI),Citation3 and more than 7 million people had in-turned eyelashes (trachomatous trichiasis) that could lead to corneal opacity and blindness.Citation4 Sub-Saharan Africa bears the largest burden of disease, with more than 80% of the cases of trachoma.Citation5 An assessment of trichiasis surgeries conducted in northern Benin in 2013 suggested that some districts were suspected-trachoma-endemic at a level that constitutes a public health problem, but in the absence of survey data, the need for public-health-level interventions was not known. We sought to map suspected endemic areas in Benin in order to decide if and where to implement trachoma control efforts.

Methods

This series of surveys was undertaken as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP),Citation6 an international effort to complete trachoma mapping in all potentially endemic populations.

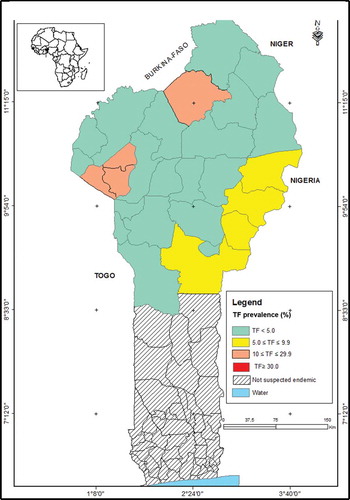

Benin, a country of 11 million inhabitants sharing borders with Nigeria (to the east), Togo (to the west), and Burkina Faso and Niger (to the north) is divided into 12 departments consisting of 77 districts. A national audit of data on the conduct of surgery for trichiasis, conducted in 2013, identified the districts to be mapped for trachoma: only 26 districts, all in the northern region, were identified, and there was no evidence or suspicion of trachoma being endemic in the remainder of the country. The total population of the northern region is 3,382,083.Citation7 Urban areas (Parakou and Natitingou) were not considered trachoma-suspect and were not included in the survey. Some districts were combined with adjacent, geographically and socio-culturally similar districts to create 11 separate evaluation units (EUs) for survey purposes; the number of districts in each EU ranged from one to four. In general, WHO recommends that trachoma surveys be implemented in populations of between 100,000 and 250,000 people;Citation8 the estimated 2014 populations of our EUs ranged from 114,659 (N’dali, Borgou Département) to 542,605 (Bassila Copargo Djougou Ouake, Donga Département) (). (The name of each EU ( and ) is a concatenation of the names of its constituent districts.)

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population in each evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benin, 2014.

Table 2. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation – follicular (TF), trachomatous inflammation – intense (TI), and trichiasis, by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Benin, 2014.

Each of the 11 separate cross-sectional population-based surveys conducted was designed to obtain EU-level prevalence estimates for TF in children aged 1–9 years; and trichiasis in persons aged 15 years and above. The GTMP survey methods that were used in this study are described in detail elsewhere.Citation9 Briefly, the target sample size was calculated to estimate, at EU level, an expected TF prevalence of 10% in 1–9-year-olds with an absolute precision of 3%, using a design effect of 2.65 and inflation by a factor of 1.2 to allow for non-response. The sample size of 1222 children for each EU was chosen as follows: in each EU, we systematically selected 23 clusters (villages) by probability proportional to size sampling. We then (because of the absence of household registers) selected 30 households in each selected village by compact segment sampling; this entailed drawing a map of the village and creating approximately equally-sized segments of about 30 households, and selecting one segment by random draw. Going house to house, field teams invited all residents of households in selected segments aged 1 year and above to be examined. For survey purposes, a household resident was defined as a person who, for the previous month or longer, shared one or more premises connected to the place where the head of the household usually sleeps (regardless of their relationship to the head of the household) and who had meals more than 3 nights per week at that location.

We examined all consenting residents for evidence of trichiasis, TF and TI, using 2.5× magnifying loupes. Additionally, we collected Global Positioning System coordinates outside the most prominent building of each household, and household-level data on access to water, sanitation, and hygiene.Citation9 For individuals found to have trichiasis, to obtain information on previous interaction with the health care system, we asked questions to determine whether health workers had previously recommended trichiasis surgery or epilation.

To prepare for the surveys, in November 2013, two ophthalmologists (AAB and JEB) underwent training and certification as GTMP grader trainers in Ethiopia. They then conducted the training of survey graders and recorders in Benin, using version 2 of the GTMP training protocols.Citation9,Citation10 All survey graders were ophthalmic clinical officers (OCOs), dedicated eye care professionals with at least two years of training in eye care. A minimum kappa of 0.7 for the diagnosis of TF in an inter-grader agreement test with 50 eyes of 50 children was required to pass the grading examination. Of the 14 OCOs enrolled in the training programme, 11 were certified as GTMP graders and became members of survey teams. Survey recorders completed training on data capture using the GTMP-LINKS app on Android smartphones.

Prior to fieldwork, we undertook a pilot test in a village not selected for any of the surveys. The 11 teams (each containing one grader and one recorder) were then deployed to the field from March to April 2014. In November 2014, we re-assessed the EU of Tchaourou because an inadequate number of 1–9-year-old children had been examined there. In April 2015, we surveyed Natitingou rural because adjacent districts were endemic for trachoma, based on the 2014 data. Therefore 13 further clusters were added to the previously sampled clusters for the Natitingou EU using the same GTMP methodology.

We uploaded all data to the GTMP secure server, and undertook standardized analyses to estimate the prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years and trichiasis in adults aged 15 years and above, in each EU. We standardized prevalence estimates for age and sex based on rural Benin population data, as previously described.Citation9 We calculated the backlog of trichiasis cases in each EU (calculated by multiplying the prevalence of trichiasis by the census population of adults). For planning purposes, we also calculated the current number of people requiring surgery or other interventions for trichiasis in order to reach the WHO elimination threshold of less than 0.2% of adults having trichiasis (defined as the backlog minus the elimination threshold).Citation11 Both the trichiasis backlog and the number needing trichiasis management to reach the elimination threshold include people with trichiasis, whether they had any previous interaction with the health system or not.

Finally, we undertook an assessment of the eye care human resources potentially available to manage trichiasis in northern Benin. This included a standard interview administered during a visit to 9 of the 14 OCOs in northern Benin, asking for the names, locations and contact details of ophthalmic colleagues, identifying ophthalmic personnel working in the region using snowball sampling. The five OCOs who could not be visited were contacted by mobile phone.

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Comite National d’Ethique pour la Recherche en Sante (070/MS/DC/SGM/DFR/CNERS/SA), and from the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (6319). Prior to examination, verbal informed consent was obtained from adults for enrollment of themselves and for children (aged under 15 years) in their care. Any participant found to have TF and/or TI was treated with 1% tetracycline eye ointment, and individuals with trichiasis or other ocular conditions were referred to the nearest eye unit.

Results

Across the 11 EUs, in total, 7719 households were surveyed in 266 clusters. A total of 46,471 people of all ages were examined (range per EU: 2449–5630), including 18,085 adults (6422 males; 11,663 females) aged 15+ years, and 23,006 children (11,678 males; 11,328 females) aged 1–9 years (). The overall participation rate was 91.5%, ranging across EUs from 87.8% to 99.2% (). The major reason for non-participation was being away from the village at the time of the survey.

The EU-level age-adjusted prevalence of TF in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 1.9% to 24.0%. Four EUs, comprising eight districts, had TF prevalences above 5%, warranting intervention ( and ). The age-adjusted prevalence of TI in 1–9-year-olds was <2% in all EUs except for the EU comprising the districts of Boukoumbe, Toukountouna, and Natitingou in Atacora Department, in which the prevalence was 5.4%. The age- and sex-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in adults ranged from 0.12% to 1.92% ( and ). Nine EUs (19 districts) had trichiasis prevalences greater than 0.2% in adults, thus requiring public health-level surgery interventions. The EU surveyed in the department of Donga (comprising the districts Bassila, Copargo, Djougou, and Ouake) and one of the EUs in the department of Atacora (comprising the districts Tanguiéta, Cobly, and Materi) had trichiasis prevalences in adults of <0.2%. The estimated total backlog of trichiasis in northern Benin is 11,457 people, with an estimated 8155 individuals needing to be offered appropriate management to meet the trichiasis component of the definition of “elimination of trachoma as a public health problem.” Among 282 people identified with trichiasis in the survey, 71 (25%) had had previous trichiasis surgery, 57 (80%) of whom came from the EU comprising the districts of Boukoumbe, Toukountouna, and Natitingou in Atacora Department.

In the 26 districts in northern Benin there are, at present, 13 OCOs and four ophthalmologists. OCOs received training at a number of training centers outside of Benin; experience in trichiasis surgery ranged from none to only a few cases. Supervision of OCOs for trichiasis surgery is limited to the OCOs in the Parakou area. Five of the 13 OCOs and the four ophthalmologists are in the urban area of Parakou. There is no OCO in Banikoara or Tchaourou, the two EUs with the highest numbers of people with trichiasis needing intervention.

Discussion

These are the first population-based prevalence surveys of trachoma in Benin, and their findings are now being used to facilitate planning and implementation of the SAFE strategy (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement)Citation12 in endemic districts. Our work indicates that these endemic districts will require different combinations of interventions, as prevalences of TF and trichiasis do not invariably exceed the respective elimination thresholds in the same places, as also observed in other trachoma endemic countries, including Cameroon.Citation13

Three of the countries bordering Benin (Nigeria, Niger, and Burkina Faso) are endemic for trachoma, while available evidence suggests that active trachoma is not a public health problem in Togo.Citation14 The Nigerian states bordering northern Benin (Kwara, Niger,Citation15 and Kebbi) have a few trachoma endemic districts, but prevalences there are not high. Large areas of the Niger and Burkina FasoCitation16 border zones are national parks and forests in which population density is very low. In fact, 2015 data available at www.trachomaatlas.org suggest that, of districts bordering Benin, only Dandi Local Government Area of Kebbi State, Nigeria and Pama Department of Burkina Faso had most recent TF prevalence estimates above the elimination threshold. There is one transit route to Burkina Faso through the districts of Natitingou and Toukountouna. Boukoumbé is far from this transit route. In these three districts, there is limited access to water, and sanitation is generally poor; this may be part of the reason for the high prevalence of TF in this area. The general absence of trachoma in the southern-most part of the northern region surveyed here probably indicates a low likelihood of disease being a public health problem further south. In addition, in 2012, the surgical records of hospitals throughout Benin were reviewed; no trichiasis cases had been operated on during the previous 2 years.

As expected, the burden of trichiasis is mostly found in areas with TF; this offers opportunities for case finding during mass drug administration and other community-based interventions. Nevertheless, there are 4246 people with trichiasis (37% of the backlog calculated here) needing management who live in areas in which the mass distribution of antibiotics is not indicated. The two EUs of Banikoara and Tchaourou account for the highest number of people needing trichiasis management (3896 or 48% of the total requirement) yet there is no OCO in either. Training (or re-training) the OCOs in Natitingou and Malanville to undertake management of trichiasis is a priority. While the long-term approach will be to place a trained OCO in Banikoara and Tchaourou and support them to provide trichiasis surgical services, a short-term measure may be to organize outreach from neighboring areas in which OCOs are based, after they have been appropriately trained and certified.Citation17

It is important to note that the 3302 people with trichiasis constituting the difference between the backlog and the number that must be treated to reach elimination prevalence thresholds all still need interventions against trichiasis in order to prevent trachomatous visual impairment. An ongoing, funded strategy to deliver services to individuals with incident trichiasis is a requirement for validation of trachoma elimination.

There were two EUs (four districts) in which TF prevalences were above 10%, thus indicating the need for at least 3 years of annual mass drug administration of antibiotics and F and E interventions. In an additional two EUs (four districts) in which prevalences of TF were between 5 and 9.9%, it is recommended that implementation of facial cleanliness promotion and environmental improvement are supplemented by one round of mass azithromycin administration. In total, over one million people live in areas that will require intervention to address active trachoma. If these measures are successful at reducing the prevalence of TF in children at impact survey, and if TF prevalence subsequently remains below 5% during surveillance, Benin will be on the pathway to elimination of trachoma as a public health problem.

The major strengths of our series of surveys are the use of gold-standard survey methodologies for estimating prevalence, good geographical sample coverage in each EU, a high participation rate, rigorous training and supervision, and standardized approaches to data cleaning and analysis. The relatively large populations of some EUs,Citation8 and the fact that we did not include examination for trachomatous conjunctival scarringCitation3 in eyes that had trichiasis,Citation18 are both potential limitations. Although it is possible that some small pockets of trachoma were missed in surveyed districts, we believe we have adequately delineated the areas of Benin in which trachoma affects sufficiently large populations to be considered a public health problem, and can now confidently chart a course towards trachoma elimination.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministry of Health and the Departmental District Health Management teams for their assistance during the survey; the private health centers that allowed staff members to participate as recorders and graders; and the community volunteers who helped to maximize population participation.

Funding

This study was funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project, implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048; and by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. USAID also supported the GTMP through the END in Asia project, implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative.

AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- World Health Assembly: Global elimination of blinding trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1998.

- Mariotti SP, Pararajasegaram R, Resnikoff S. Trachoma: looking forward to Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020 (GET 2020). Am J Trop Med Hyg 2003;69( 5Suppl.):33–35.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ 1987;65:477–483.

- World Health Organization: Global WHO Alliance for the Elimination of Blinding Trachoma by 2020. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2012;87(17):161–168.

- Mariotti SP, Pascolini D, Rose-Nussbaumer J. Trachoma: global magnitude of a preventable cause of blindness. Br J Ophthalmol 2009;93:563–568.

- Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The global trachoma mapping project. Community Eye Health 2014;27(85):18.

- Institut National de la Statistique et de l’Analyse Economique: Recensement Général de la Population et de l’Habitation (RGPH4) [www.insae-bj.org]. Porto-Novo: INSAE,2013.

- World Health Organization: Report of the 3rd global scientific meeting on trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19–20 July 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015;22:214–225.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global trachoma mapping project: training for mapping of trachoma (version 2) [ Available at: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/resources/global-trachoma-mapping-project-training-mapping-trachoma]. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control, 2013.

- World Health Organization. Validation of elimination of trachoma as a public health problem (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016.

- Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, et al. Trachoma control: a guide for program managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2006.

- Noa Noatina B, Kagmeni G, Mengouo MN, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in the Far North region of Cameroon: results of a survey in 27 Health Districts. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2013;7(5):e2240.

- Dorkenoo AM, Bronzan RN, Ayena KD, et al. Nationwide integrated mapping of three neglected tropical diseases in Togo: countrywide implementation of a novel approach. Trop Med Int Health 2012;17:896–903.

- Adamu A, Mpyet C, Muhammad N, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Niger State, North Central Nigeria: results of 25 population-based prevalence surveys carried out with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2016;23(S1):63–69.

- Schemann JF, Guinot C, Ilboudo L, et al. Trachoma, flies and environmental factors in Burkina Faso. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2003;97:63–68.

- Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, et al. Trichiasis surgery for trachoma (2nd ed). Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015.

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachomatous Trichiasis: Cape Town, 4–6 November, 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.