ABSTRACT

Purpose: Trachoma is to be eliminated as a public health problem by 2020. To help the process of planning interventions where needed, and to provide a baseline for later comparison, we set out to complete the map of trachoma in Afar, Ethiopia, by estimating trachoma prevalence in evaluation units (EUs) of grouped districts (“woredas”).

Methods: We conducted seven community-based surveys from August to October 2013, using standardised Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) survey methodologies.

Results: We enumerated 5065 households and 18,177 individuals in seven EUs covering 19 of Afar’s 29 woredas; the other ten were not accessible. 16,905 individuals (93.0%) were examined, of whom 9410 (55.7%) were female. One EU incorporating four woredas (Telalak, Dalefage, Dewe, Hadele Ele) was shown to require full implementation of the SAFE strategy for three years before impact survey, with a trachomatous inflammation-follicular (TF) prevalence in 1–9-year-olds of 17.1% (95%CI 9.4–25.5), and a trichiasis prevalence in adults aged ≥15 years of 1.2% (95%CI 0.6–2.0). Five EUs, covering 13 woredas (Berahle, Aba’ala, Dupti, Kurri, Elidihare, Ayesayeta, Afamboo, Bure Mudaitu, Gewane, Amibara, Dulecho, Dalolo, and Konebo), had TF prevalences in children of 5–9.9% and need one round of azithromycin mass treatment and implementation of the F and E components of SAFE before re-survey; three of these EUs had trichiasis prevalences in adults ≥0.2%. The final EU (Mile, Ada’ar) had a sub-threshold TF prevalence and a trichiasis prevalence in adults just >0.2%.

Conclusion: Trachoma is a public health problem in Afar, and implementation of the SAFE strategy is required.

Introduction

Trachoma is the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness . An estimated 3.2 million people are thought to have trichiasis, the potentially blinding stage of the disease.Citation1 Trachoma limits access to education and prevents individuals from being able to work or care for themselves or their families, and can destroy the economic well-being of entire communities, keeping families shackled within a cycle of poverty as the disease and its long-term effects pass from one generation to the next. Ethiopia is considered to have the highest prevalence of trachoma of any country, with a survey in 2005–2006 carried out at national level estimating an overall prevalence of active trachoma of 40.1% in children aged 1–9 years.Citation2

The Afar Region in the North-East of Ethiopia has a population of 1.7 million people, with the lowest population density of any region in Ethiopia.Citation3 The region is one of extremes, playing host to the hottest inhabited place on earth, the Danakil Depression, where daytime temperatures reach up to 54°C, along with the active volcano Erta Ale. The topography ranges from desert plains in the north-east to fertile river flats and foothills on the western boundary with Oromia, Tigray and Amhara Regions. 90% of the population are pastoralistsCitation4 relying on highly vulnerable water sources—a factor that is commonly associated with a high prevalence of trachoma.Citation5 In the 2005–2006 survey, the estimated prevalence of active trachoma was only 1.9% among children aged 1–9 years in Afar, but with only a total of 350 households visited in ten clusters across the whole of the Afar Region, finer resolution surveys are needed to provide appropriate data for trachoma intervention planning.

The clinical signs of trachoma can be readily identified by trained healthcare workers using the World Health Organization’s simplified trachoma grading system.Citation6,Citation7 Conjunctival Chlamydia trachomatis infection in children may manifest as small white follicles in the central zone of the upper tarsal conjunctiva; if 5 or more follicles (each of ≥0.5mm diameter) are present then trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) is said to be present. Repeat infections can lead to scarring of the tarsal conjunctiva that can produce changes to the function and morphology of the eyelid, such that eyelashes are mis-directed to touch the globe. This is known as trachomatous trichiasis. Over time, persistent abrasion by eyelashes may lead to opacification of the normally clear cornea, with associated visual disturbance or blindness, for which there is currently no cure.Citation6,Citation7

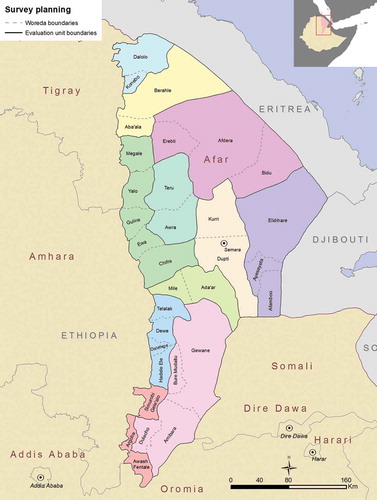

We conducted seven population-based prevalence surveys in evaluation units (EUs) of grouped districts (woredas) to complete the map of trachoma in all accessible and secure woredas in Afar Region (). The objectives in each EU were to estimate the baseline prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years, and to estimate the baseline prevalence of trichiasis in those aged 15 years or greater.

Methods

The study was carried out as seven independent cross-sectional, community-based surveys, as part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP)Citation8, using a standardised methodology common to all GTMP surveys.Citation9 We created EUs covering all of rural Afar Region, but due to insecurity and flooding, completing surveys in 10 woredas was not possible. The sample size of 1019 children aged 1–9 years per EU allows estimation of a TF prevalence of 10% with a precision of +/-3%, with 95% confidence. From the latest available census dataCitation10, it was anticipated that 25 clusters of 30 households would be sufficient to achieve this number. The sample size for trichiasis estimates was all adults present and consenting to examination in sampled households.

Survey teams comprised a trachoma grader, a data recorder, and a driver. Both graders (ophthalmic nurses) and recorders were required to pass a standardised (version 1) GTMP training course with exit examination, as previously described.Citation9

A two-stage sampling methodology was used.Citation9 Kebeles were used as the primary sampling unit. A list of all rural kebeles and their populations was obtained from the health office of each respective woreda. Kebeles were selected with probability proportional to their population size, to allow equal weighting of all individuals in each EU. At the second stage, Gots (kebele sub-divisions of approximately 30 households) were randomly selected by drawing lots on the day of survey. All households in a sampled got were included, with all residents in sampled households aged 1 year and above enumerated.

Verbal consent for examination was recorded for individuals present. GPS coordinates of each household were recorded at the time of survey. All consenting participants were examined for clinical signs of trachoma using the WHO simplified trachoma grading system.Citation6,Citation7 All data were recorded on a smartphone using an electronic data collection tool developed for the survey (LINKS, Taskforce for Global Health, Decatur, USA).

Data analysis

Data were analysed according to GTMP protocols.Citation9 TF prevalence was adjusted for age in 1 year age bands, and trichiasis prevalence was adjusted for sex and age in 5 year age bands using the 2007 Afar Census data.Citation10 Outcomes were adjusted at kebele (cluster)-level to account for the clustered design of the surveys, with each EU outcome prevalence being the mean of all constituent adjusted kebele-level proportions. This was carried out to reduce the variance of population-level estimates of survey outcomes, where the sampled population may be non-representative through stochastic variation or sampling bias.Citation11 The mean of all EU-level outcome estimates was used to estimate overall outcomes for this series of seven surveys, with confidence intervals estimated by bootstrapping cluster-level estimates, with stratification of clusters at EU-level. All analyses were carried out in R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013).Citation9

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committees of the Afar Regional Health Bureau and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (6319). Permission to undertake the survey was obtained from each respective zone, woreda and kebele office. Communities were sensitised in advance to the purpose and procedures for the survey. Informed verbal consent was obtained from each individual aged ≥15 years. In those under 15 years of age, informed verbal consent was obtained from a parent or guardian. All individuals with active trachoma identified through the surveys were provided with 1% tetracycline eye ointment to apply twice daily for 6 weeks, and those with trichiasis were referred to the nearest health institution for surgical correction. Residents of selected gots had the right not to participate in the survey, not to respond to uncomfortable questions and to stop responding to questions or terminate examination at any time that they wanted to stop, without impacting on their normal health care.

Results

A total of 18,177 people were enumerated over 7 EUs covering 19 woredas. 5065 households were visited in a total of 178 clusters from 13th August, 2013 to 6th October, 2013. Details of individuals enumerated in the 7 EUs surveyed are shown in .

Table 1. Individuals enumerated in seven trachoma prevalence surveys, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Afar, Ethiopia, 2013.

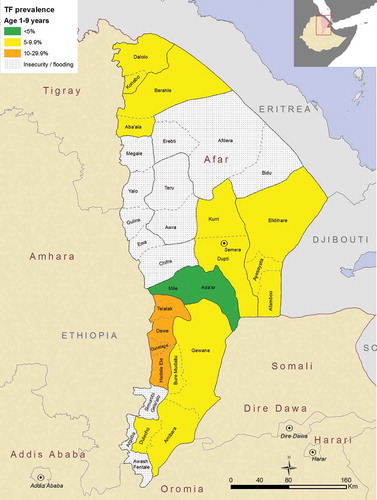

The overall adjusted prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years for the 7 EUs combined was 8.2% (95%CI 6.5–10.0%), although there was considerable variation in adjusted prevalence between EUs. The lowest adjusted TF prevalence (4.1%, 95%CI 2.1–6.8) was reported in the EU covering Mile and Ada’ar woredas. The highest adjusted prevalence of TF (17.1%, 95%CI 9.4–25.5) was found in the EU covering the Telalak, Delefage, Dewe and Hadele Ele woredas (, ).

Table 2. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation –follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Afar, Ethiopia, 2013.

Figure 2. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Afar, Ethiopia, 2013.

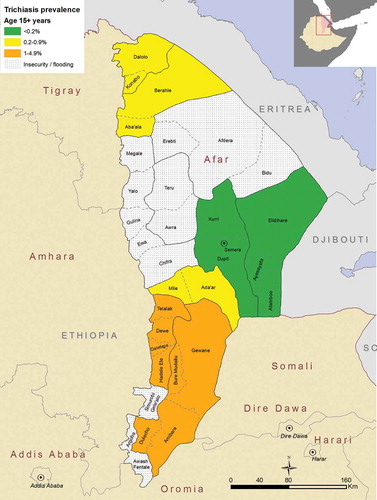

A total of 103 cases of trichiasis were identified in the 7 surveys in those aged 15 years or greater, with the overall prevalence in those aged 15 years or greater in the area surveyed estimated to be 0.5%. The lowest adjusted trichiasis prevalence in those aged 15 years or greater (0.1%) was in the EU covering Dupti and Kurii woredas. The highest adjusted trichiasis prevalence was found in the two Eus covering Telalak, Delefage, Dewe, and Hadele Ele woredas, and Bure Mudaitu, Gewane, Amibara, and Dulecho woredas, both of which had an estimated adjusted trichiasis prevalence of 1.2%. (, ).

Table 3. Prevalence of trichiasis in those aged 15 years or greater, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Afar, Ethiopia, 2013.

Discussion

When compared to EUs in several other regions of Ethiopia involved in the GTMPCitation12–Citation14, or Amhara RegionCitation15, the prevalences of trachoma in Afar EUs were low, though the relatively low prevalences are matched in data from northern Ethiopian Somali RegionCitation16, to which Afar is also adjacent. Studies have previously associated trachoma with hot, dry areas with relative water scarcity.Citation17–Citation19Afar has very low levels of access to water and sanitationCitation2, and the average temperature are amongst the highest in the world. It is possible that very high temperatures limit the breeding potential of the flies that are thought to spread trachoma.Citation20 Large scale spatial variation in risk of trachoma has been studied elsewhere, notably in NigeriaCitation21, although there, interestingly, risk of trichiasis was higher with higher mean annual temperature—albeit within a considerably cooler range (21.8–28.7°C) than experienced in Afar. Aspects of the Afari culture may also play a part. For example, in the last censusCitation10, 96% of the population of Afar identified themselves as Muslim, and ritual washing associated with daily prayer may limit spread of infection. However, this is speculation; data on behaviour were not collected as part of our surveys.

World Health Organization (WHO) targets for trachoma elimination are a TF prevalence <5% in children, and a trichiasis prevalence <0.2% in those aged 15 years or greater (equivalent to a trichiasis prevalence of <0.1% of the total population).Citation22 In these surveys, one EU covering two woredas (Mile and Ada’ar) had a prevalence of TF in children below 5%, but a prevalence of trichiasis in adults just greater than 0.2%. Only one EU, comprising the woredas Telalak, Dalefage, Dewe and Hadele Ele, had a TF prevalence above the 10% level at which mass drug administration (MDA) with azithromycin is recommended for three or more years.Citation23 The relatively high prevalence in this EU might be because it shares a boundary with Amhara Region. It also might be attributed to similar weather, culture, or geography, factors related to any or all of which could be conducive to transmission.Citation17–Citation20 The boundaries between Afar and Amhara are not clearly defined by the local population, the majority of whom are pastoralists undertaking seasonal migrations between Afar and the highland areas of Amhara in search of grazing land and water. Whilst Amhara has had an active trachoma elimination programme for many years, Afar has not, and these migrations might contribute to the continuing presence of trachoma in both areas.

Five EUs (made up of 13 woredas) had TF prevalences in children between 5 and 9.9%. The current practice of the International Trachoma Initiative for such EUs is to make available a single round of azithromycin MDACitation24, which should be given alongside implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategy, and followed by repeat survey. Given the close proximity of these woredas to Amhara, coordination between the regions may be important.

The estimates for trichiasis prevalence have confidence intervals much larger than those for the TF estimates. This is because a larger sample size is needed to give precise estimates for rarer outcomes, particularly at the 0.2% elimination threshold for trichiasis around which public health-level intervention decisions are made. For reasons of practicality, the sample size used for the trichiasis prevalence estimates for each EU was all those aged ≥15 years in enumerated households. These are population-based samples, not convenience samples, but they provide estimates with relatively low repeatability. Despite this limitation, it is hoped that they are useful as a guide for programme managers.

Though we present overall TF and trichiasis estimates for our series of surveys, in and and in the results section above, these should not be interpreted as region-level prevalences: not all of Afar has been surveyed here, and the areas for which we have data are not all contiguous. We could not access ten woredas during scheduled mapping in the region, due to inaccessibility and insecurity. Plans are currently being developed to undertake surveys in these woredas. Completion of the baseline map in Afar will facilitate planning for regional trachoma elimination.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The paper has not been published nor submitted simultaneously for publication elsewhere.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Eliminating Trachoma: Accelerating towards 2020. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2016.

- Berhane Y, Alemayehu W, Bejiga A. National Survey on Blindness, Low Vision and Trachoma in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia; 2006.

- Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Population and Housing Census Report 2007. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission; 2008.

- Daniel T, Tezera G, Wendessen G. Pastoralist Perspectives of Poverty Reduction Strategy Program- Experiences and Lessons from Afar Region of Ethiopia. Addis Ababa. 2009.

- Solomon A, Mabey D. Trachoma. BMJ Clin Evid. 2007;2007.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(4):477–483.

- Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, et al. Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):982–1011. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.4.982-1011.2004.

- Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Community Eye Health. 2014;27(85):18.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):214–225. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401.

- Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia. Population and Housing Census - Afar Region. Addis Ababa: Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission; 2007.

- Li W, Stanek EJ 3rd, Bertone-Johnson ER. Should adjustment for covariates be used in prevalence estimations? Epidemiol Perspect Innov. 2008;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1742-5573-5-2.

- Bero B, Macleod C, Alemayehu W, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia: Results of 79 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(6):392–405. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717.

- Sherief ST, Macleod C, Gigar G, et al. The Prevalence of Trachoma in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: Results of 11 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Completed as Part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):94–99. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1250917.

- Adera TH, Macleod C, Endriyas M, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region, Ethiopia: Results of 40 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Carried Out with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):84–93. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1247876.

- Emerson PM, Ngondi J, Biru E, et al. Integrating an NTD with One of “The Big Three”: Combined Malaria and Trachoma Survey in Amhara Region of Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(3). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000197.

- Duale AB, Ayele NN, Macleod CK et al. Epidemiology of trachoma and its implications for implementing the “SAFE” strategy in Somali Region, Ethiopia: results of 14 population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(sup1):25–32. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2017.1409358

- Ramesh A, Kovats S, Haslam D, Schmidt E, Gilbert CE. The Impact of Climatic Risk Factors on the Prevalence, Distribution, and Severity of Acute and Chronic Trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(11). doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002513.

- Mahande MJ, Mazigo HD, Kweka EJ. Association between water related factors and active trachoma in Hai district, Northern Tanzania. Infect Dis Poverty. 2012;1. doi: 10.1186/2049-9957-1-10.

- Hagi M, Schemann J-F, Mauny F, et al. Active trachoma among children in Mali: Clustering and environmental risk factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(1):e583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000583.

- Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9415):1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15891-1.

- Smith JL, Sivasubramaniam S, Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Solomon AW, Gilbert C. Multilevel Analysis of Trachomatous Trichiasis and Corneal Opacity in Nigeria: The Role of Environmental and Climatic Risk Factors on the Distribution of Disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:7. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003826.

- World Health Organization. Report on the 2nd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Geneva, 25-27 August, 2003. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003.

- Solomon A, Zondervan M, Kuper H, Buchan J, Mabey D, Foster A. Trachoma Control: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

- International Trachoma Initiative. Diagram on Decision Making for the Antibiotic Treatment of Trachoma. Decatur: Task Force for Global Health; 2015.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4), Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.