ABSTRACT

Purpose: The World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) global trachoma elimination programme recommends mapping of trachoma at district level for planning of elimination activities in affected populations. This study aimed to provide data on trachoma prevalence for the Area Councils of Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory (FCT).

Methods: Using the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) protocols, in March and April 2014, we conducted a population-based cross-sectional survey in each of the six Area Councils of FCT. Signs were defined based on the WHO simplified grading scheme.

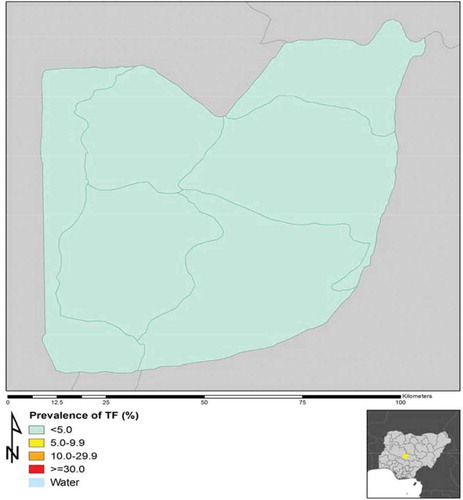

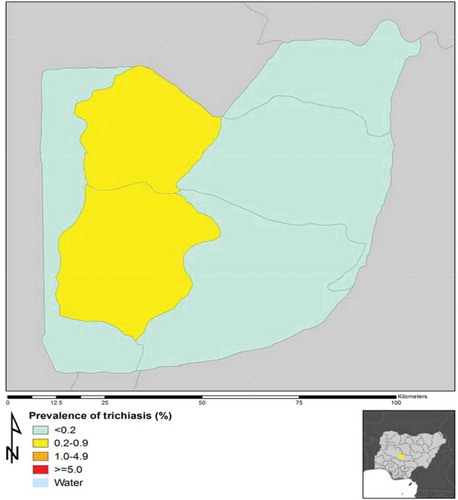

Results: 98% to 100% of the targeted households were enrolled in each Area Council. The number of children aged 1–9 years examined per Area Council ranged from 867 to 1248. The number of persons aged ≥15 years examined ranged from 1302 to 1836. The age-adjusted prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular in 1–9-year-olds was <5% in each Area Council. The age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in those aged ≥15 years ranged from 0.0% to 0.3%; two Area Councils (Gwagwalada and Kwali) had prevalences above the 0.2% elimination threshold. The proportion of households with access to improved latrines and water sources ranged from 17 to 90% and 39 to 85% respectively.

Conclusions: Gwagwalada and Kwali Area Councils need to perform more trichiasis surgeries to attain the trichiasis elimination prevalence target of 0.2% in persons aged ≥15 years. No Area Council requires mass antibiotic administration for the purposes of trachoma’s elimination as a public health problem. All Area Councils need to accelerate provision of access to improved water sources and latrine facilities, to achieve universal coverage.

Introduction

Trachoma, a neglected tropical disease,Citation1 is a chronic conjunctivitis caused by Chlamydia trachomatis, and the leading infectious cause of blindness. It accounted for 1.4–3% of the global burden of blindness in 2010.Citation2,Citation3 To attain global elimination of trachoma by the year 2020 (GET2020), mapping of trachoma is required at district level in areas suspected of being endemic, in order to plan for the implementation of elimination activities.Citation4 Such prevalence data are also a useful advocacy tool for engaging relevant stakeholders.Citation5 The Federal Capital Territory (FCT) of Nigeria had not previously been mapped for trachoma. It is located in the central part of the country and in 2011 had an estimated population of 2,238,751Citation6 living in six Area Councils (ACs).

This article reports the findings of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP)Citation7,Citation8 in FCT. The objectives of the study were to determine the prevalence of active (inflammatory) trachoma in children aged 1–9 years in each of the six ACs; to determine the prevalence of trichiasis in persons aged ≥15years in each of the six ACs; and to assess the prevalence of household-level access to water and sanitation facilities in each of the six ACs.

Subjects and methods

We conducted a population-based cross-sectional prevalence survey using the GTMP protocol (version 2)Citation7 in each AC. Fieldwork was conducted in the months of March and April 2014.

Sample size

For each AC, as for evaluation units elsewhere in Nigeria, we estimated that a sample of 25 households in each of 25 clusters would facilitate assessment of 1019 children aged 1–9 years, allowing for non-response. Citation7,Citation9–Citation14

Ethical considerations

The ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) (reference 6319) and the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (reference NHREC/01/01/2007) granted approval for the study. The FCT Health Services Department granted administrative permission. Consent of participants was obtained and documented in the LINKS Android smartphone app.Citation7 Trachoma graders cleaned their hands with an alcohol-based gel, between examination of successive persons. Subjects diagnosed with trichiasis were appropriately referred, and 1% tetracycline eye ointment was offered to those with conjunctivitis, including active trachoma.

Sampling design

A two-stage cluster random sampling design was employed, with probability- proportional-to-size systematic selection used to identify 25 clusters in each AC. In each cluster, 25 households were selected using compact segment sampling. All residents of each selected household aged ≥1 year who had lived in the area for at least 6 months were enumerated. At each house, the head of the household or another appropriate adult household member was asked questions on access to water and sanitation, using GTMP protocols; the latrine, if present, was inspected.Citation7 Survey definitions were as described elsewhere.Citation7 Trachoma was graded using the WHO simplified grading scheme,Citation15 2.5× loupes, and sun- or torch-light.

Data management

All collected data were directly entered into an Android phone via the LINKS app, and from there uploaded to the GTMP server. Data were then cleaned and analysed by the GTMP data manager (RW) to determine the prevalences of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) and trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI) in children aged 1–9 years, and of trichiasis in persons aged ≥15 years. Prevalences of TF and TI were adjusted for age in 1-year age bands, while the prevalence of trichiasis was adjusted for gender and age in 5-year age bands. The trichiasis burden was calculated for each AC as the product of the trichiasis prevalence and the estimated number of resident persons aged ≥15 years, with the latter determined by multiplying the AC’s total population estimate at last census by 0.598Citation6 We calculated the confidence intervals for each LGA by bootstrapping, with replacement, 10,000 resamples of 25 clusters; using the adjusted cluster-level proportions of each sign to generate prevalence estimates for each resample; and fixing the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of the distributions of estimates as the lower and upper confidence interval bounds, respectively.

Results

The response rate for households surveyed ranged from 98% in Abaji to 100% in Abuja Municipal. The number of children aged 1–9 years examined per AC ranged from 867 in Gwagwalada to 1248 in Abaji. The number of persons aged ≥15 years examined ranged from 1302 in Bwari to 1836 in Abaji.

Prevalence of trachoma

The age-adjusted prevalence of TF and TI in children aged 1–9 years and the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of trichiasis in persons aged ≥15 years, are shown for each AC in . The prevalence of TF was <5% in each AC, while the prevalence of trichiasis was ≥0.2% only in Kwali (0.2%) and Gwagwalada (0.3%) ( and ).

Table 1. Numbers of enumerated individuals examined, who refused examination or were absent, and adjusted trachoma prevalences, by Area Council, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014. (TF = trachomatous inflammation—follicular; TI = trachomatous inflammation—intense).

Prevalence of access to water and sanitation

shows water and sanitation coverage in each AC. Residents of Kuje had the worst access to improved water sources (39% of households) and latrines (17% of households). For 28% of households in Abaji, the nearest improved or unimproved source of washing water to which they had access was further than one kilometer from the residence.

Table 2. Household-level water and sanitation coverage by Area Council, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014.

Discussion

The targeted sample size for determining the prevalence of TF was only obtained in two of the six AC-level surveys that we report here (), because the mean number of children resident per household was lower than anticipated on the basis of available census data. However, for each AC, the entirety of the 95% confidence interval for the TF prevalence estimate in 1–9-year-olds was well below the elimination threshold of 5%Citation16,(), and point estimates for prevalence (rather than upper bounds of confidence intervals) are generally accepted to be the figures used for decision-making. We therefore feel justified in saying that we have demonstrated the absence of levels of active trachoma in Nigeria’s FCT that would be considered significant to public health, and that no AC requires mass drug administration of antibioticsCitation17 for the purposes of eliminating active trachoma.

The urban and sub-urban nature of the FCT population, with its relatively high standard of living, may partly explain the paucity of active trachoma in these surveys. There also seems to be limited risk of infection being introduced from adjacent states: our findings in FCT are comparable to those from GTMP-supported surveys in neighboring KadunaCitation12 and NigerCitation13 States, in which the majority of Local Government Areas (LGA)(including all those sharing borders with FCT) had TF prevalences contemporaneously estimated to be <5%. In Nasarawa State, which borders FCT to its east and south, surveys conducted in 2007–2008 generated TF prevalence estimates for 13 LGAs, eight of which were ≥5%, including four that were ≥10%.Citation18 However, the SAFE strategyCitation19 has subsequently been implemented where required in Nasarawa, and unpublished data suggest that TF prevalences there are now considerably lower than in 2007–2008. In short: in this part of Nigeria, active trachoma appears to be controlled or coming under control.

The trichiasis burden in FCT that we estimated was generally low. Though the confidence intervals of our prevalence estimates are quite wide, on the basis of our data, two of six ACs (Gwagwalada and Kwali) need to provide trichiasis surgical services to reach the elimination prevalence target of <0.2% unmanaged trichiasis in persons aged ≥15years.Citation16 In the absence of existing community-based trichiasis surgery services and with only one trained trichiasis surgeon in FCT, this will require a specific initiative. There is a need to train and certify at least two other trichiasis surgeons from the pool of eighteen ophthalmic nurses available in FCT. In addition to surgeon training and certification, FCT Health Services and its partners should work with primary eye care workers to determine the most effective and efficient means of undertaking community-based screening, counselling and referral of trichiasis patients to certified surgeons.Citation14,Citation20–Citation23 A participatory planning meeting could be convened to review disease prevalence, service awareness and service utilization, leading on to the development of a collaborative plan to address the trichiasis burden.

Despite the relatively low prevalence of trachoma, our data highlight the fact that access to water and latrine facilities in and around Nigeria’s capital city is inadequate, such that even the residents of Abuja Municipal AC do not have 100% access to these basic services. Though the prevalence of access was highest in Abuja Municipal, the absolute number of households that still lack access to improved water sources or latrines was also highest there of any of the six ACs included in this study (). From a percentage coverage point of view, Kuje AC lagged furthest behind the others, and particular attention will need to be paid towards improving services there.

Table 3. Recommended actions by Area Council, Federal Capital Territory, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2014.

It’s important to note that “access to an improved water source” and “access to a latrine” are relatively low bars to clear; the situation with respect to access to safe and reliable services on the household premises would be considerably worse. This presents a major challenge for attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals,Citation24 for which access to “safely managed” water and sanitation services is the target. Government institutions responsible for WASH should take the lead to convene periodic participatory planning for the sector, inclusive of all stakeholder groups. This should be driven by evidence, including consideration, for example, of the data presented here, in order to identify the most vulnerable people.Citation25 This may lead to delineation of sources of finance and community strengths that could promote household ownership and use of latrines, as well as exploration of roadblocks that hinder such a process.Citation26 It could also lead to consensus on how to target efforts and how to better coordinate those efforts amongst implementers. Alongside this work, water provision at community level may be promoted and supported.

This study has revealed that active trachoma is not a public health problem in FCT and that relatively few trichiasis surgeries are needed to attain the threshold prevalence for trichiasis elimination in each AC. There is a need to intensify efforts to improve sustainable access to safe water and sanitation, not only to ensure that active trachoma elimination will be maintained, but to meet human rights, and to prevent a range of other water-related health issues.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the GTMP grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support health ministries to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM). He and BAG are now staff members of the World Health Organization; the authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article and they do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer-reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. WHO alliance for the global elimination of blinding Trachoma by the year 2020. Progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2013. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2014;89(39):421–428.

- Bourne RRA, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Global Health. 2013;1(6):e339–49. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X.

- Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96(5):614–618. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539.

- Smith JL, Haddad D, Polack S, et al. Mapping the global distribution of trachoma: why an updated atlas is needed. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5(6):e973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000973.

- Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, Buchan JC, Mabey DCW, Foster A. Trachoma control: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

- National Bureau of Statistics (Nigeria). Annual Abstract of Statistics, 2012. 2014.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck AL, Courtright P, et al. The global trachoma mapping project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):214–225. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401.

- Engels D. The global trachoma mapping project: a catalyst for progress against neglected tropical diseases. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):1–2. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1257139.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Bauchi State, Nigeria: results of 20 local government area-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(1):39–45. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1238945.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Katsina State, Nigeria: results of 34 District-Level Surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(1):55–62. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1236975.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Trachoma Mapping in Gombe State, Nigeria: results of 11 local government area surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;00(00):1–6. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1230633.

- Muhammad N, Mpyet C, Adamu MD, et al. Mapping Trachoma in Kaduna State, Nigeria: results of 23 local government area-level, population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(1):46–54. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1250918.

- Adamu MD, Mpyet C, Muhammad N, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Niger State, North Central Nigeria: results of 25 population-based prevalence surveys carried out with the global Trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(1):63–69. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1242757.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Kano State, Nigeria: results of 44 local government area-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2017; [In press]. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1265657.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65(4):477–483.

- World Health Organization. Validation of Elimination Trachoma as a Public Health Problem. World Health Organization. (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). 2016.

- Evans JR, Solomon AW. Antibiotics for trachoma. Cochrane Database Sys Rev. 2011;3:CD001860.

- Mapping trachoma in Nasarawa and Plateau States, central Nigeria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(1):14–19. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.165282.

- Francis V, Turner V. Achieving Community Support for Trachoma Control (WHO/PBL/93.36). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Faal H, Toit Du R, Monye H, Graham R. Community Health Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa. London: International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness; 2015.

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Eliminating trachoma: accelerating towards 2020. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2016.

- Habtamu E, Wondie T, Aweke S, et al. Posterior lamellar versus bilamellar tarsal rotation surgery for trachomatous trichiasis in Ethiopia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(3):e175–84. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00299-5.

- Solomon AW. Optimising the management of trachomatous trichiasis. Lancet Global Health. 2016;4(3):e175–84. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)00004-8.

- World Health Organization. Health in 2015: from MDGs to SDGs. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Boisson S, Engels D, Gordon BA. Water, sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on neglected tropical diseases: a new Global Strategy 2015–20. Int Health. 2016;8(Suppl 1):i19–i21. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv073.

- Lefevre P, Kolsteren P, De Wael MP, et al. Comprehensive Participatory Planning and Evaluation (CPPE) Antwerp: Institute of Tropical Medicine. 2001.