ABSTRACT

Purpose: The purpose of these surveys was to determine the prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years and trichiasis prevalence in persons aged ≥15 years, in 13 Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Taraba State, Nigeria.

Methods: The surveys followed Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP) protocols. Twenty-five households were selected from each of 25 clusters in each LGA, using two-stage cluster sampling providing probability of selection proportional to cluster size. Survey teams examined all the residents of selected households aged ≥1 year for the clinical signs TF, trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI) and trichiasis.

Results: The prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years in the 13 LGAs ranged from 0.0–5.0%; Ussa LGA had the highest prevalence of 5% (95%CI: 3.4–7.2). Trichiasis prevalence ranged from 0.0–0.8%; seven LGAs had trichiasis prevalences above the threshold for elimination. The backlog of trichiasis in the 13 LGAs (estimated combined population 1,959,375) was 3,185 people. There is need to perform surgery for at least 1,835 people to attain a trichiasis prevalence in each LGA of <0.2% in persons aged ≥15 years. In six of the 13 LGAs, 80% of households could access washing water within 1 km of the household, but only one LGA had >80% of households with access to improved latrines.

Conclusion: One of 13 LGAs requires antibiotic mass drug administration for active trachoma. Community-based trichiasis surgery needs to be provided in seven LGAs. There is a need to increase household-level access to improved washing water and latrines across the State.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Trachoma is a disease of global public health importance, putting about 200 million people across the world potentially at risk of blindness.Citation1,Citation2 Visual impairment and blindness from trachoma occur as a result of corneal opacities, the outcome of healed corneal ulcers, which result from entropion, trichiasis, and alterations to the composition and volume of tears. These can be induced by trachoma-related scarring of the conjunctivae during resolution of episodes of active (inflammatory) trachoma.

There has been significant reduction in the prevalence of active trachoma globally in the last decade, owing to implementation of the WHO-recommended SAFE strategy (Surgery for trichiasis, Antibiotics to clear infection, and promotion of Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement to reduce transmission).Citation1,Citation2 However, barely four years before the target set for global elimination of trachoma as a public health problem (GET2020)Citation2, both active and blinding stages of the disease are endemic in some parts of Northern Nigeria, as reported in recent surveys.Citation3–Citation7

To achieve the elimination of trachoma, there is need to conduct trachoma surveys in suspected districts where no data exist, to ascertain the magnitude of the disease. Only three of 16 Local Government Areas (LGAs–the equivalent of districtsCitation8) of Taraba State, North Eastern Nigeria had previously been mapped.Citation9 The purpose of the current project was to determine the prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in children aged 1–9 years, and the prevalence of trichiasis among persons aged ≥15 years, in the outstanding 13 LGAs of Taraba State, so that the governments and partners could understand the need or otherwise for the establishment of a trachoma elimination programme.

Subjects and methods

A series of LGA-level, population-based cross-sectional surveys were conducted between December, 2013 and February, 2014 in13 LGAs of Taraba State. Taraba State has 16 LGAs and an estimated population (projected from the 2006 census)Citation10 of 2,294,800. The sample size calculations, field team training and certification protocols, data collection, data processing and analysis techniques all followed the procedures of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP),Citation11,Citation12 which have been previously published.Citation13

Team training and fieldwork

Version 2 of the GTMP training system was used.Citation12 Each LGA was treated as a single evaluation unit. In each LGA, to attain the calculated sample of 1019 children aged 1–9 years, 25 villages (clusters) were sampled using a systematic technique with probability of selection proportional to the village size, and (based on the expectation of a household having a mean of two children aged 1–9 years), 25 households were then sampled in each selected village, using the random walk methodology.Citation15–Citation18

In each enrolled household, the head of the household or their proxy provided the information on sources of water for hygiene and drinking, and the type of facilities used for sanitation; these were confirmed through direct observation by field teams. GTMP-certifiedCitation13 graders proceeded to examine all members of the household aged one year and older, who had been resident in the household for at least 6 months. Consent was obtained from adults, while the parents/caregivers gave consent to examine the children. Graders used 2.5 × magnifying loupes, and assessed each subject for the signs of trichaisis, TF, and trachomatous inflammation–intense (TI). All findings were entered into the GTMP-LINKS app running on Android cell phones.Citation13

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) (reference 6319) and the National Health Research Ethics Committee of Nigeria (NHREC/01/01/2007), while Taraba State Ministry of Health granted administrative approval. Verbal consent was obtained by the Research Assistant from each adult in a language he or she understood and parents provided consent for children. All individuals with trichiasis were referred to a nearby facility for corrective surgery provided by a trained surgeon; surgery was offered at no cost to the patient. Children with conjunctivitis, including active trachoma, received two tubes of 1% tetracycline eye ointment to be used for six weeks. Subjects with other ocular pathologies were also referred appropriately.

Definitions

The WHO simplified grading scheme was used to grade trachoma.Citation19 Households were defined as individuals living in the same compound and eating from the same cooking pot. In concordance with conventions of the WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP), an improved water source was defined as a source of water that was constructed in such a way as to protect it from external contamination, particularly with faecal matter. An improved latrine was defined as any latrine that by virtue of its construction hygienically separated human excreta from human contact. We did not examine the eyes with trichiasis for evidence of scarring: WHO guidance to do so (in order to distinguish between trachomatous and non-trachomatous trichiasis) was not producedCitation20 until after this series of surveys was completed. We therefore refer to estimated prevalences of trichiasis, rather than of TT, in this paper.

Data management and analysis

Data were managed according to GTMP protocols, as described elsewhere.Citation13 We used R statistical software (R core team, Austria, Vienna 2014)Citation21 for analysis. The main outcome indicators were the age-adjusted prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years, and the age- and gender-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in persons aged ≥15 years. Odds ratios to determine associations were calculated from the crude prevalences in Epi Info version 7.0, with statistical significance at p < 0.05. We calculated the trichiasis backlog in each LGA by multiplying the estimated prevalence of trichiasis in persons aged ≥15 years by 56% of the total population in the LGA (56% of the Nigerian population is aged ≥15 years).Citation10 Confidence intervals were determined for each LGA by bootstrapping adjusted cluster-level proportions of each sign, and taking the 2.5th and 97.5th centiles of 10,000 replicates.

Results

In the 13 LGAs combined, in 8,035 households, a total of 14,625 children 1–9 years (48.9% females) and 23,557 adults (58.3% females) aged ≥15 years consented to participate, and were examined. A further 340 children (2.1% of resident 1–9-year-olds) and 184 adults (0.7% of resident ≥15-year-olds) refused participation. One hundred and sixty nine children (1.1% of resident 1–9-year-olds) and 2,010 adults (7.8% of resident ≥15-year-olds) were absent on the day of the relevant survey team’s visit. Fieldwork was completed by 15 teams.

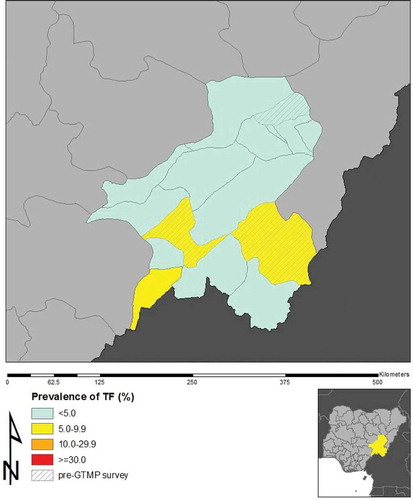

The LGA-level prevalence of TF in children aged 1–9 years ranged from 0.0% to 5.0% (). Across the 13 LGAs, the combined crude prevalence of TF in children 1–9 years old was 1.8% (95% CI: 1.6–2.1). The prevalence of TF in males (1.5%; 95% CI: 1.2–1.8) was significantly lower than in females (2.2%; 95% CI: 1.9–2.6); with an odds ratio of 1.5 (95% CI: 1.2–1.9; p = 0.001). Ussa LGA had the highest TF prevalence (5.0%; 95% CI: 3.4–7.2). and show the distribution of TF across the LGAs.

Table 1. Local Government Area (LGA)-level prevalences of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) and trichiasis, Taraba State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2013–2014.

Figure 1. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation–follicular (TF) in 1–9-year-old children, by Local Government Area, Taraba State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2013–2014.

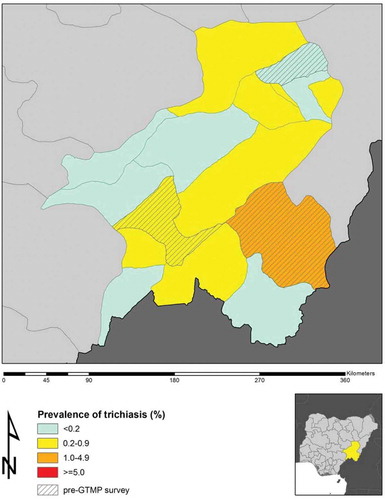

In persons aged ≥15 years, the combined crude trichiasis prevalence across the 13 LGAs surveyed was 0.5% (95% CI: 0.4–0.6). The prevalence in females (0.6%; 95% CI: 0.5–0.8) was significantly higher than in males (0.3%; 95% CI: 0.2–0.5); odds ratio 1.9 (95% CI: 1.3–2.9), p = 0.002. Seven of 13 LGAs had trichiasis prevalences above the threshold for elimination (0.2% in persons aged ≥15 years), with estimates ranging between 0.2% and 0.8% ().Citation19

The backlog of trichiasis in these 13 Taraba LGAs (which had a combined estimated population of 1,959,375), was 3,185 people. There is a need to offer trichiasis surgery to at least 1,835 individuals with trichiasis across these 13 LGAs, in order to attain in each one the WHO-set prevalence target for unmanaged trichiasis within the definition of “elimination as a public health problem”. As shown in and , seven of the 13 LGAs have trichiasis backlogs that need to be cleared to relegate trichiasis to the status of not being a public health issue.

Table 2. Local Government Area (LGA)-level estimates of the trichiasis backlog, Taraba State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2013–2014.

Figure 2. Prevalence of trichiasis in adults aged ≥15 years, by Local Government Area, Taraba State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2013–2014.

At least 80% of households in six (46%) of 13 LGAs could access washing water within 1 kilometre; however, only one of 13 LGAs had >80% of households with access to improved latrines ().

Table 3. Household-level access to washing water and improved latrines, by local government area (LGA), Taraba State, Nigeria, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, 2013–2014.

Discussion

The prevalence of TF was less than 5% in all but one (Ussa) of the 13 LGAs of Taraba State mapped in this series of surveys. Previous studies (conducted in 2009) reported TF prevalences of 5.0% in Gashaka and 6.1% in DongaCitation9 which are LGAs that were not included in the present study. According to current recommendations, one round of high coverage antibiotic mass drug administration is indicated in Ussa LGA (and in Gashaka and Donga LGAs), in addition to implementation of the F & E components of the SAFE strategy; such an approach has proven highly effective in eliminating active trachoma elsewhere.Citation22 While there have been no specific trachoma elimination activities in Taraba since the 2009 surveys were conducted, disease prevalence is unlikely to have remained exactly the same as recorded then. Where water supply and sanitation conditions, education and/or access to health care have improved, the prevalence of trachoma is likely to have fallen.Citation23,Citation24

This work established that of 13 LGAs mapped; only Sardauna LGA had at least 80% of its households having access to improved latrines. Although in six LGAs, residents of >80% of households have to walk <1 kilometre to access water for washing, improved latrines were accessible to <50% of households in 10 of 13 LGAs. To maintain the low levels of active trachoma seen in this series of surveys, there is a need to sustain and improve upon F and E components of the SAFE strategy in all LGAs of Taraba State. Access to improved latrines is associated with lower risk of trachoma.Citation25–Citation29 Community awareness should be raised on the health benefits of using improved latrines. Government agencies and non-governmental organizations should mobilise needed resources to improve access to water and latrines, with full community participation and ownership. Sustainable Development Goal three foresees a world in which every community has access to clean water and improved sanitation.Citation30 Achieving this goal will have an impact on the elimination of trachoma and other neglected tropical diseases, and improve the quality of life of the populace.Citation31

Blindness from trachoma is thought to be preventable if good quality, corrective lid surgery is performed in persons with trachomatous trichiasis. Seven of the 13 LGAs included in this series of surveys had trichiasis prevalences of >0.2% in persons aged ≥15 years, the level at which WHO considers trichiasis to represent a threat to public health.Citation32 The trichiasis backlog in the study area is 3185 people. Although at least 1835 people with (mostly bilateral) trichiasis will need to have corrective eyelid surgeries to achieve public health goals in seven LGAs, resources and structures should be put in place to continue providing this care to all those with trichiasis, including to deal with new cases that will inevitably occur in the coming years. Several previous studies have reported the magnitude of trichiasis backlogs elsewhere in Northern Nigeria,Citation3–Citation7,Citation14−Citation18 and it is now abundantly clear that there are tens of thousands of people with sight-threatening complications of trachoma in this area. Ophthalmic nurses will need to be trained and retrained (according the guidelines provided by WHOCitation33) to provide corrective lid surgeries at community level for these people, in order to head off an avalanche of avoidable blindness. Presently, of the 36 ophthalmic nurses in active service in Taraba State, only three are trained trichiasis Surgeons. This number is unfortunately inadequate to provide the number of surgeries needed to provide the necessary services, and achieve the trachoma elimination targets.

Conclusion

To eliminate trachoma in Taraba State, trichiasis surgery and provision of water and sanitation should be scaled up as soon as possible. There is a need for mass drug administration in Ussa LGA.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Funding

This study was principally funded by the GTMP grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support ministries of health to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide. The GTMP was also funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the LSHTM. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Eliminating Trachoma: Accelerating Towards 2020. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2016.

- World Health Assembly. Global elimination of blinding trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly. Geneva. Resolution WHA51.11. May 16, 1998.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Mohammed A, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Kano state, Nigeria: results of 44 district-level surveys. Ophthalmic Epi. 2017;24(3):195–203. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1265657.

- Mpyet C, Lass BD, Yahaya HB, Solomon AW. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in Kano state, Nigeria. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040421.

- Mpyet C, Ogoshi C, Goyol M. Prevalence of trachoma in Yobe State, north-eastern Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(5):303–307. doi: 10.1080/09286580802237633.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Trachoma Mapping in Gombe State, Nigeria: results of 11 Local Government Area Surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(6):406–411. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1230633.

- Muhammad N, Damina M, Umar MM, Isiyaku S. Trachoma prevalence and risk factors in eight local government areas of Zamfara State. Niger J Ophthalmol. 2015;23:48–53. doi: 10.4103/0189-9171.170989.

- World Health Organization. Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA. Geneva: World Health Organization; July 19–20, 2010.

- Report of trachoma population based survey in 3 Local Government Areas of Taraba State. Mssion To Save The Helpless (MITOSATH). 2009. [Unpublished].

- National Population Commission. Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Nigeria: National and State Population and Housing Tables, Priority Tables (Volume 1). Abuja: National Population Commission; 2006. 2009.

- Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The global trachoma mapping project. Community Eye Health. 2014;27(85):18.

- Engels D. The global trachoma mapping project: a catalyst for progress against neglected tropical diseases. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):1–2. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1257139.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck AL, Courtright P, et al. The global trachoma mapping project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):214–225. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: Training for Mapping of Trachoma (Version 2). London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2013. http://www.trachomacoalition.org/resources/global-trachoma-mapping-project-training-mapping-trachoma].

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Katsina State, Nigeria: Results of 34 District-Level Surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(Sup 1)55–62. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1236975.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Bauchi State, Nigeria: Results of 20 Local Government Area-Level Surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(Sup 1):39–45. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1238945.

- Muhammad N, Mpyet C, Adamu MD, et al. Mapping Trachoma in Kaduna State, Nigeria: Results of 23 Local Government Area-Level, Population-Based Prevalence Surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(Sup 1):46–54. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1250918.

- Adamu MD, Mpyet C, Muhammad N, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Niger State, North Central Nigeria: Results of 25 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Carried Out with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(Sup 1):63–69. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1242757.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, et al. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:477–483.

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachomatous Trichiasis. (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.5). Cape Town, Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. November 4–6, 2015.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2014. ISBN 3-900051-07-0. http://www.R-project.org.

- Kalua K, Chisambi A, Chainyanya D, et al. One round of azithromycin MDA adequate to interrupt transmission in districts with prevalence of trachomatous inflammation-follicular of 5.0-9.9%: Evidence from Malawi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2018;12(6):e0006543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006543.

- Dolin PJ, Faal H, Johnson GJ, et al. Reduction of trachoma in a sub-Saharan village in absence of a disease control programme. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1511–1512. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01355-X.

- Hoechsmann A, Metcalfe N, Kanjaloti S, et al. Reduction of trachoma in the absence of antibiotic treatment: evidence from a population-based survey in Malawi. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2001;8(2–3):145–153. doi: 10.1076/opep.8.2.145.4169.

- Courtright P, Sheppart J, Lane S, et al. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:322–325. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.322.

- Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1093–1098. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15891-1.

- Haile M, Tadesse Z, Gebreselassie S, et al. The association between latrine use and Trachoma: a secondary cohort analysis from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89(4):717–720. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0299.

- Adera TH, Macleod C, Endriyas M, et al. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Trachoma in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region, Ethiopia: Results of 40 Population-Based Prevalence Surveys Carried Out with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(Sup 1):84–93. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1247876.

- Elshafie BE, Osman KH, Macleod C, et al. The Epidemiology of Trachoma in Darfur States and Khartoum State, Sudan: results of 32 population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(6):381–391. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2016.1243718.

- United Nations General Assembly. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015 (A/70/L.1). Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations; 2015.

- Boisson S, Engels D, Gordon BA, et al. Water, sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on neglected tropical diseases: A new Global Strategy 2015–20. Int Health. 2016;8(Suppl 1):i19–i21. doi: 10.1093/inthealth/ihv073.

- World Health Organization. Validation of Elimination of Trachoma as a Public Health Problem (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, Mariotti S, Greene G, West SK. Trichiasis Surgery for Trachoma. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group