ABSTRACT

Purpose: In 2015, to determine where interventions are needed to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem from Egypt, we initiated population-based prevalence surveys using the Global Trachoma Mapping Project platform in four suspected-endemic marakez (districts; singular: markaz) of the governorates of Elmenia and Bani Suef.

Methods: In each markaz, 30 households were selected in each of 25 villages. Certified graders examined a total of 3682 children aged 1–9 years in 2993 households, noting the presence or absence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) and trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI) in each eye. A total of 5582 adults aged ≥15 years living in the same households were examined for trachomatous trichiasis (TT). Household-level access to water and sanitation was recorded.

Results: Three of four marakez had age-adjusted TF prevalence estimates in 1–9-year olds of >10%; the other markaz had a TF prevalence estimate of 5–9.9%. Estimates of the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of unmanaged TT in adults ranged from 0.7% to 2.3%. Household-level access to water and sanitation was high. (We did not, however, measure use of water or sanitation facilities.)

Conclusions: Each of the four marakez surveyed has trachoma as a public health problem, with a need for implementation of the SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement) strategy. Further mapping is also required to determine the need for interventions in other areas of Egypt.

Background

With an estimated 89 million residents,Citation1 Egypt is the most populous country in the Middle East. However, it fares better than some of its neighbours on a variety of health indicators (including deaths from malaria, maternal and infant mortality rates, and prevalence of HIV); neglected tropical diseases such as schistosomiasis, soil-transmitted helminths, and trachoma are endemic.Citation2,Citation3

Trachoma’s presence in Egypt was documented in the Ebers medical papyrus dating from 1500 BC.Citation4 During the Napoleonic wars in the early 1800s, troops deployed to Egypt were heavily affected.Citation5 At the beginning of the twentieth century, in some areas, nearly all young children developed active disease, and more than two-thirds of adults were observed to have trichiasis;Citation6,Citation7 from 1903 to 1923, seminal work on trachoma was undertaken in Egypt by Arthur Ferguson MacCallan.Citation8 In the 1970s and 1980s, it was still a widespread problem, including in the capital, Cairo.Citation9,Citation10 In the mid-1980s, hyperendemic trachoma was seen in two rural communities of Beheira Governorate in the Nile Delta: active trachoma was present in 59% of 3-year olds, while trichiasis and/or entropion were seen in children as young as 9 years old and affected a staggering 75% of adult females.Citation11,Citation12

In 1999, a population-based survey in the Nile Delta Governorate of Elmenofiya found that 37% of 2–6-year olds had active trachoma, while 6.5% of adults had trichiasis.Citation13 A 2002 population-based survey of Elmenia Governorate estimated the prevalence of active trachoma in 2–10-year olds to be 42%, and the prevalence of trichiasis in ≥50-year olds to be 6.2%.Citation14 In 2003, trachoma rapid assessments (TRAs)Citation15 were undertaken in 15 villages of Elfayoum Governorate. The village-level proportions of 2–10-year-old children observed to have active trachoma ranged from 16% to 85%.Citation16 A further series of modified TRAs was undertaken in 2010–2011 in 78 villages of four governorates; the proportions of villages in which ≥10% of children examined had the active trachoma sign trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF)Citation17 were 6/20 in Elfayoum, 18/20 in Elmenia, 19/20 in Elmenofiya, and 16/18 in Kafr Elsheikh.Citation18

Transmission of trachoma’s causative agent, Chlamydia trachomatis,Citation19 is thought to be facilitated by a combination of factors including poor sanitation,Citation11,Citation20 inadequate access to water for face-washing,Citation21,Citation22 and overcrowding.Citation23,Citation24 Despite economic improvements across Egypt and the introduction of sewerage to many areas of the Nile Delta in recent decades, trachoma is thought to remain a threat to public health in parts of the country. We sought to collect contemporary data necessary for planning interventions against this disease: specifically, population-based prevalence estimates of TF, trachomatous trichiasis (TT) and access to water and sanitation.Citation25,Citation26

Methods

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was received from the Research Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (reference numbers 6319 and 8355) and the Egypt National Ministry of Health Ethics Committee (20 May 2013). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all adults examined and from the household head on behalf of children in their care.

Study design

We used the principles and protocols of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP).Citation27,Citation28 The survey sample size in each evaluation unit was based on an expected TF prevalence of 10% and a desire to be 95% confident of estimating the true TF prevalence with absolute precision of 3%. The design effect was estimated at 2.65, leading to our sample size estimate of 1019 1–9-year-olds, which was then inflated by 20% to account for partial non-response.Citation27 We did not calculate a specific sample size for TT, for which prevalences are generally very low, but instead used a household-sampling approach in which a fixed number of households were selected in each cluster, with that number determined by the number of children that we needed to include to generate an adequate sample size for TF.Citation27

We undertook population-based surveys in the Governorates of Elmenia and Bani Suef, using the markaz (district; plural: marakez) as the evaluation unit. Due to constraints in availability of personnel, only four surveys could be conducted. Elmenia Governorate was believed (on the basis of recent researchCitation29) to have a high TT burden; its most northern, most southern, and a central markaz were selected for inclusion. Bani Suef Governorate lies just to the north of Elmenia Governorate. Its most southern markaz was surveyed, based on the understanding that local conditions here were most similar to those in Elmenia. Within each markaz, clusters were selected by creating a list of villages with corresponding village-level population estimates, then systematically sampling from that list with probability proportional to population size.Citation26 In order to select sufficient households in which 1019 × 1.2 = 1222 one-to-nine-year olds would be resident, 25 villages were selected in each markaz, and 30 households were chosen in each selected village. A compact segment sampling technique was employed to select households.Citation30–Citation35

Fieldwork

Trachoma grading was undertaken according to the WHO simplified grading scheme,Citation17 using 2.5× binocular loupes (OptiVISOR, Donegan Optical, Lenexa, KS, USA) and sunlight illumination. Graders and data recorders were trained prior to the surveys and certified according to the standardized training protocols of the GTMP, as described elsewhere.Citation27 Version 3 of the training system was used.Citation36

All consenting residents in the household aged ≥1 year were examined for trichiasis, TF, and trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI). Eyes with trichiasis were considered to have TT if they also had TS, or if the eyelid could not be everted for conjunctival examination by the grader. Participants identified to have trichiasis were asked whether they had been offered surgery or epilation by a health professional. All children identified as having active trachoma (TF and/or TI in one or both eyes) were provided with two tubes of 1% tetracycline eye ointment and their parents or guardian were instructed on how to use it. Participants with trichiasis were referred for surgery.

Data recording and analysis

Data entry and upload was accomplished via the bespoke Open Data Kit-based GTMP data capture system running on Android smartphones.Citation27 Data were encrypted during transit and stored in a secure server with only the study investigators having access; cleaning was undertaken by the GTMP data managers (AB and RW). TF data were adjusted at cluster level for the age of those examined, in 1-year age bands. TT data were adjusted at cluster level for age and gender of those examined, in 5-year age bands. Markaz-level estimates were generated by taking the arithmetic mean of the adjusted cluster-level proportions. Confidence intervals for TF and TT prevalence estimates were determined by bootstrapping the adjusted cluster-level proportions of each sign, with replacement, over 10,000 replicates.

Results

Surveys were conducted from 29 November to 25 December 2015 in Abu Quorquas, Deir Mawass and Matai marakez of Elmenia Governorate, and Elfashn markaz of Bani Suef Governorate. Field teams visited a total of 2993 households in 100 clusters across the four marakez. In total, of 3708 1–9-year-old children resident in selected households, 3682 were examined ().

Table 1. Adults and children resident, examined, absent and refused, by markaz, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Egypt, 2015.

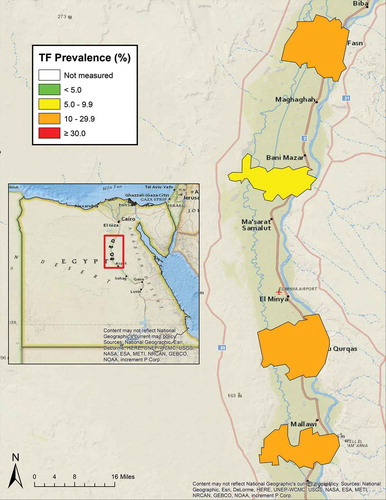

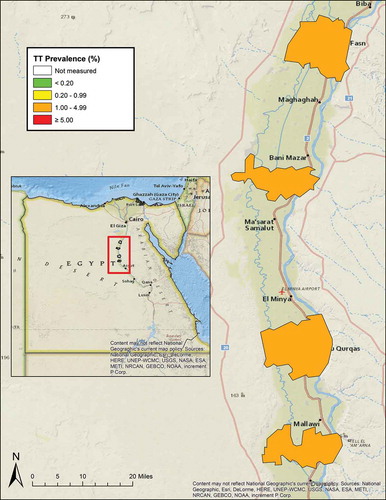

The estimated age-adjusted markaz-level TF prevalence in 1–9-year olds ranged from 8.4% to 25.3% across the four marakez (, ). A total of 134 individuals aged ≥15 years had TT, of whom 46 had bilateral TT. The estimated age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of TT exceeded 1% in each of the four marakez (, ). In Elfashn, 14 (64%) of the 22 individuals identified as having TT had been offered surgery or epilation by the health system; corresponding proportions elsewhere were 8/26 (31%, Matai), 17/59 (29%, Deir Mawass), and 7/27 (26%, Abu Quorquas).

Table 2. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) and trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI) in 1–9-year olds, and prevalence of trachomatous trichiasis (TT) in ≥15-year olds, four marakez of Elmenia and Bani Suef Governorates, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Egypt, 2015.

Figure 1. Prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) in 1–9-year olds, four marakez of Elmenia and Bani Suef Governorates, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Egypt, 2015.

Figure 2. Prevalence of trachomatous trichiasis (TT) in ≥15-year olds, four marakez of Elmenia and Bani Suef Governorates, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Egypt, 2015.

Based on these prevalence estimates for TF and TT, applied to 2017 population estimates, for trachoma elimination purposes, >1.7 million people in the four marakez should receive antibiotics, facial cleanliness promotion, and environmental improvement and 8712 people require eyelid surgery to correct TT ().

Table 3. Estimated numbers of people needing surgery (S) for trachomatous trichiasis (TT), antibiotics (A), facial cleanliness (F), and environmental improvement (E) interventions, for trachoma elimination purposes, in four marakez of Elmenia and Bani Suef Governorates, Egypt, 2017.

Discussion

In the absence of an effective vaccine,Citation37 the public health approach to preventing trachoma blindness involves reducing C. trachomatis transmission intensity by maximising access to water and sanitation and encouraging personal hygiene;Citation38–Citation40 periodically clearing prevalent infection with antibiotics;Citation41 and preventing further trachoma-related vision loss in those who already have trichiasis through provision of quality eyelid surgery.Citation42 These interventions together comprise the “SAFE strategy”: surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, environmental improvement.Citation43 The SAFE strategy worksCitation44,Citation45 and is recommended by the World Health Organization, which leads an Alliance aiming to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem by 2020. SAFE strategy interventions, however, have to compete for prioritization in a crowded public health landscape. Robust prevalence data are required to make the case for funding. Though there are some limitations of our work here—particularly the relatively large size of evaluation units surveyed—we believe that our estimates are of evidence-based metrics, are reproducible, and justify planning for SAFE strategy implementation in the areas surveyed.

Table 4. Household access to water and sanitation facilities, four marakez of Elmenia and Bani Suef Governorates, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Egypt, 2015.

The prevalence of unmanaged TT ranged from 0.7% (Elfashn) to 2.3% (Deir Mawass) in the four marakez surveyed here. Elimination of trachoma as a public health problem requires that the prevalence of TT unknown to the health system be reduced to <0.2% in adults.Citation50 Community-based case identification and provision of quality lid surgery by certified operatorsCitation51 is urgently needed in these populations to stem the tide of trachoma-related blindness and visual impairment.

These findings indicate the urgent need to implement the SAFE strategy for trachoma elimination in all four marakez. F and E interventions should incorporate established techniques for achieving sustained behaviour change.Citation52 Priority should be given to Deir Mawass, where prevalences of both TF and TT were the highest of the four marakez, and the proportion of people with TT who had previously been offered management was the lowest. In all, however, >1.7 million people in these four marakez need services to eliminate trachoma as a public health problem—and it is likely that other markaz in Egypt will also need interventions, a hypothesis that will need to be confirmed or refuted through further population-based surveys.Citation25,Citation53 It is currently estimated that at least 29 marakez still need to undergo baseline surveys. Of Egypt’s international neighbours, only SudanCitation23,Citation54 is currently thought to have a public health problem from trachoma, so cross-border issues are not currently believed to be a priority here.

Global progress towards the target of eliminating trachoma as a public health problem has recently gathered pace, with a number of countries now validated by the World Health Organization as having achieved that milestone at national level.Citation55 Armed with the evidence generated by this series of surveys and those that will follow, Egypt can now proceed to trachoma action planningCitation56 and engage with relevant stakeholders, starting along the path to national trachoma elimination.

Acknowledgments

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project was supported by a grant from the United Kingdom’s Department for International Development (DFID; ARIES: 203145) to Sightsavers, which led a consortium of non-governmental organizations and academic institutions to support health ministries to complete baseline trachoma mapping worldwide; and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), through the ENVISION project implemented by RTI International under cooperative agreement number AID-OAA-A-11-00048, and the END in Asia project implemented by FHI360 under cooperative agreement number OAA-A-10-00051. A committee established in March 2012 to examine issues surrounding completion of global trachoma mapping was initially funded by a grant from Pfizer to the International Trachoma Initiative. AWS was a Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow (098521) at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and is now, like SB and BAG, a member of staff at the World Health Organization. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this article, which do not necessarily represent the views, decisions or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated. None of the funders had any role in project design, in project implementation or analysis or interpretation of data, in the decisions on where, how or when to publish in the peer reviewed press, or in preparation of the manuscript.

References

- United Nations Statistics Division. Population and Vital Statistics Report. Statistical Papers, Series A Vol. LXIX: Data Available as of 1 January 2017. New York: United Nations; 2017

- Hotez PJ, Kassem M. Egypt: its artists, intellectuals, and neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10:e0005072. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005072.

- Hotez PJ, Savioli L, Fenwick A. Neglected tropical diseases of the Middle East and North Africa: review of their prevalence, distribution, and opportunities for control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1475. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001475.

- Bryan CP. The Papyrus Ebers: Translated from the German Version. London: Bles; 1930

- Taylor HR. Trachoma: A Blinding Scourge from the Bronze Age to the Twenty-First Century. East Melbourne: Centre for Eye Research Australia; 2008

- Wilson RP. Ophthalmic survey in village in Bahtim. Ann Rep Giza Mem Ophthalmol Lab. 1929;4:72–86.

- Attiah MAH, El Togby AF. Factors influencing the course of trachoma. Bull Ophthalmol Soc Egypt. 1937;30:137–142.

- MacCallan M. Arthur Ferguson MacCallan CBE, MD, FRCS (1872-1955), trachoma pioneer and the ophthalmic campaign in Egypt 1903-1923. J Med Biogr. 2018;26(1):59–67. doi: 10.1177/0967772016643540.

- Said ME, Goldstein H, Korra A, El-Kashlan K. Prevalence and causes of blindness in urban and rural areas of Egypt. Public Health Rep. 1970;85:587–599. doi:10.2307/4593913.

- International Eye Foundation. Findings from the South Cairo Eye Disease Survey: Integrated Urban Primary Eye Care Program. Bethesda, MD: International Eye Foundation; 1985

- Courtright P, Sheppard J, Schachter J, Said ME, Dawson CR. Trachoma and blindness in the Nile Delta: current patterns and projections for the future in the rural Egyptian population. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73:536–540. doi:10.1136/bjo.73.7.536.

- Courtright P, Sheppard J, Lane S, Sadek A, Schachter J, Dawson CR. Latrine ownership as a protective factor in inflammatory trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:322–325. doi:10.1136/bjo.75.6.322.

- Ezz Al Arab G, Tawfik N, El Gendy R, Anwar W, Courtright P. The burden of trachoma in the rural Nile Delta of Egypt: a survey of menofiya governorate. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:1406–1410. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.12.1406.

- Elarab GE, Khan M. Estimation of the prevalence of trachoma in Egypt. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:392. doi:10.1136/bjo.2009.165795.

- Negrel AD, Taylor HR, West S. Guidelines for Rapid Assessment for Blinding Trachoma (WHO/PBD/GET/00.8). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001

- Ezz Al Arab G. Trachoma Rapid Assessment and Planning for Intervention: A Pilot Study in Fayoum Governorate. Research Brief No. 9. Cairo: Partnership in Development Research, American University in Cairo; 2003

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:477–483.

- National Task Force of Trachoma. Rapid Assessment of Active Trachoma in Egypt. Cairo: Ministry of Health and Population; 2011

- Hadfield J, Harris SR, Seth-Smith HMB, et al. Comprehensive global genome dynamics of Chlamydia trachomatis show ancient diversification followed by contemporary mixing and recent lineage expansion. Genome Res. 2017;27:1220–1229. doi:10.1101/gr.212647.116.

- Garn JV, Boisson S, Willis R, et al. Sanitation and water supply coverage thresholds associated with active trachoma: modeling cross-sectional data from 13 countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006110. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006110.

- Bailey R, Downes B, Downes R, Mabey D. Trachoma and water use; a case control study in a Gambian village. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:824–828. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(91)90470-J.

- West S, Munoz B, Lynch M, et al. Impact of face-washing on trachoma in Kongwa, Tanzania. Lancet. 1995;345:155–158. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90167-1.

- Elshafie BE, Osman KH, Macleod C, et al. The epidemiology of trachoma in Darfur States and Khartoum State, Sudan: results of 32 population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:381–391. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1243718.

- Taleo F, Macleod CK, Marks M, et al. Integrated mapping of Yaws and Trachoma in the Five Northern-Most Provinces of Vanuatu. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005267. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0005267.

- Smith JL, Haddad D, Polack S, et al. Mapping the global distribution of trachoma: why an updated atlas is needed. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e973. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000973.

- Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, Buchan JC, Mabey DCW, Foster A. Trachoma Control: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006

- Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma mapping project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:214–225. doi:10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401.

- Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The global trachoma mapping project. Community Eye Health. 2014;27:18.

- Mousa A, Courtright P, Kazanjian A, Bassett K. A community-based eye care intervention in Southern Egypt: impact on trachomatous trichiasis surgical coverage. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2015;22:478–483. doi:10.4103/0974-9233.167808.

- Abashawl A, Macleod C, Riang J, et al. Prevalence of Trachoma in Gambella Region, Ethiopia: results of three population-based prevalence surveys conducted with the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:77–83. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1247875.

- Adamu Y, Macleod C, Adamu L, et al. Prevalence of trachoma in Benishangul Gumuz Region, Ethiopia: results of seven population-based surveys from the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:70–76. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1247877.

- Adera TH, Macleod C, Endriyas M, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples’ Region, Ethiopia: results of 40 population-based prevalence surveys carried out with the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:84–93. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1247876.

- Bero B, Macleod C, Alemayehu W, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for trachoma in oromia regional state of Ethiopia: results of 79 population-based prevalence surveys conducted with the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:392–405. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1243717.

- Sherief ST, Macleod C, Gigar G, et al. The prevalence of trachoma in Tigray Region, Northern Ethiopia: results of 11 population-based prevalence surveys completed as part of the global trachoma mapping project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23:94–99. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1250917.

- Phiri I, Manangazira P, Macleod CK, et al. The burden of and risk factors for trachoma in selected districts of Zimbabwe: results of 16 population-based prevalence surveys. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(sup 1):181–191. doi:10.1080/09286586.2017.1298823.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: Training for Mapping of Trachoma (Version 3). Available at: http://www.trachomacoalition.org/node/122. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2014

- Solomon AW, Mabey DC. Modeling the economic net benefit of a potential vaccination program against ocular infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Vaccine. 2005;23:5281–5282. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.05.042.

- Rabiu M, Alhassan MB, Ejere HO, Evans JR. Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD004003. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004003.pub4.

- Ejere HO, Alhassan MB, Rabiu M. Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003659.

- Boisson S, Engels D, Gordon BA, et al. Water, sanitation and hygiene for accelerating and sustaining progress on neglected tropical diseases: a new Global strategy 2015-20. Int Health. 2016;8(Suppl 1):i19–i21. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihv073.

- Evans JR, Solomon AW. Antibiotics for trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD001860.

- Burton M, Habtamu E, Ho D, Gower EW. Interventions for trachoma trichiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:CD004008.

- Francis V, Turner V. Achieving Community Support for Trachoma Control (WHO/PBL/93.36). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993

- Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, et al. Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: A cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;368:589–595. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69202-7.

- Hammou J, El Ajaroumi H, Hasbi H,AN, Hmadna A, El Maaroufi A. In Morocco, the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem becomes a reality. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e250–e1. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30023-2.

- Harding-Esch EM, Sillah A, Edwards T, et al. Mass treatment with azithromycin for trachoma: when is one round enough? Results from the PRET trial in the Gambia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2115. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002115.

- West SK, Bailey R, Munoz B, et al. A randomized trial of two coverage targets for mass treatment with azithromycin for trachoma. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2415. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002415.

- Oswald WE, Stewart AE, Kramer MR, et al. Active trachoma and community use of sanitation, Ethiopia. Bull. World Health Organ. 2017;95:250–260. doi:10.2471/BLT.16.177758.

- Freeman MC, Garn JV, Sclar GD, et al. The impact of sanitation on infectious disease and nutritional status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.05.007.

- World Health Organization. Validation of Elimination of Trachoma as a Public Health Problem (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016

- Merbs S, Resnikoff S, Kello AB, Mariotti S, Greene G, West SK. Trichiasis Surgery for Trachoma. 2nd. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015

- Delea MG, Solomon H, Solomon AW, Freeman MC. Interventions to maximize facial cleanliness and achieve environmental improvement for trachoma elimination: A review of the grey literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006178. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006178.

- Mpyet C, Kello AB, Solomon AW. Global elimination of trachoma by 2020: a work in progress. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22:148–150. doi:10.3109/09286586.2015.1045987.

- Hassan A, Ngondi JM, King JD, et al. The prevalence of blinding trachoma in northern states of Sudan. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1027. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001027.

- World Health Organization. WHO alliance for the global elimination of trachoma by 2020: progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2014-2016. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 2017; 92: 359–368.

- International Coalition for Trachoma Control. Trachoma Action Planning. London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2015

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Sarah Bovill (8), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

Key: (1) Advisory Committee, (2) Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, (3) Epidemiological Support, (4) Ethiopia Pilot Team, (5) Master Grader Trainers, (6) Methodologies Working Group, (7) Prioritisation Working Group, (8) Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, (9) Statistics and Data Analysis, (10) Tools Working Group, (11) Training Working Group