ABSTRACT

Purpose: Previous phases of trachoma mapping in Pakistan completed baseline surveys in 38 districts. To help guide national trachoma elimination planning, we set out to estimate trachoma prevalence in 43 suspected-endemic evaluation units (EUs) of 15 further districts.

Methods: We planned a population-based trachoma prevalence survey in each EU. Two-stage cluster sampling was employed, using the systems and approaches of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. In each EU, residents aged ≥1 year living in 30 households in each of 26 villages were invited to be examined by trained, certified trachoma graders. Questionnaires and direct observation were used to evaluate household-level access to water and sanitation.

Results: One EU was not completed due to insecurity. Of the remaining 42, three EUs had trichiasis prevalence estimates in ≥15-year-olds ≥0.2%, and six (different) EUs had prevalence estimates of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF) in 1–9-year-olds ≥5%; each EU requires trichiasis and TF prevalence estimates below these thresholds to achieve elimination of trachoma as a public health problem. All six EUs with TF prevalences ≥5% were in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Province. Household-level access to improved sanitation ranged by EU from 6% to 100%. Household-level access to an improved source of water for face and hand washing ranged by EU from 37% to 100%.

Conclusion: Trachoma was a public health problem in 21% (9/42) of the EUs. Because the current outbreak of extremely drug-resistant typhoid in Pakistan limits domestic use of azithromycin mass drug administration, other interventions against active trachoma should be considered here.

Introduction

Trachoma is a neglected tropical diseaseCitation1 and the leading infectious cause of blindness worldwide.Citation2 Trachomatous inflammation— follicular (TF) and/or trachomatous inflammation—intense (TI) are signs of active trachoma that can occur when certain strainsCitation3,Citation4 of the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis infect the conjunctivae. Trichiasis is a complication of trachoma that occurs after multiple episodes of infection and associated inflammation,Citation5 typically in adulthood.Citation6–Citation8 It is characterized by in-turned eyelashes touching the eyeball, which may lead to pain, corneal ulceration, corneal scarring, and visual impairment.Citation9–Citation11

To eliminate trachoma as a public health problem,Citation12 the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends implementation of the SAFE strategy: Surgery to redirect in-turned eyelashes away from the eye; Antibiotics to clear infection; and Facial cleanliness and Environmental improvement to reduce transmission.Citation13,Citation14 In order to plan and implement SAFE interventions, population-based prevalence surveys of TF and trichiasis are needed in districts suspected to be trachoma-endemic.Citation15,Citation16 Public health-level implementation of S is indicated in districts where trachomatous trichiasis prevalence is ≥0.2% in persons aged ≥15 years, while public health-level implementation of A, F and E is indicated in districts where TF prevalence is ≥5% in children aged 1–9 years.Citation17

In Pakistan in the 1950s, trachoma was believed to account for >60% of all blindness nationally.Citation18 The country now has a population of over 200 million people, 63% of whom live in rural areas.Citation19 In addition to its Federal Capital Territory (Islamabad), Pakistan is comprised of four provinces (Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab and Sindh), two autonomous territories (Azad Jammu & Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan) and the Federally Administered Tribal Area. These province-level units are further split into the successively lower administrative tiers of 34 divisions, 149 districts (zillahs), and 588 sub-districts (tehsils).

From 2002 to 2004, the National Trachoma Task Force of Pakistan oversaw Trachoma Rapid Assessments (TRAs)Citation20 covering 233 villages in Baluchistan (49 TRAs), North-West Frontier Province [renamed Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2010] (69), Punjab (67), Sindh (23) and Northern Areas [renamed Gilgit-Baltistan in 2009] (25).Citation21 Based on these TRAs, from 2011 to 2013, prevalence surveys were undertaken over three phases in 38 districts. In each of those districts, 70 villages were chosen with a probability-proportional-to-size sampling strategy. In every selected village, systematic sampling was used to select households to facilitate examination of 100 adults. In every second selected village, 100 children were also examined. This produced relatively large sample sizes of 7000 adults and 3500 children per district.Citation22 In Punjab province, the districts of DG Khan (0.77%), Hafizabad (0.39%), Narowal (1.01%) and Vehari (0.36%) had trichiasis prevalences in adults ≥0.2%; elsewhere, only Chitral (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 1.3%), Pishin (Baluchistan, 0.47%) and Skardu (Gilgit Baltistan, 0.93%) exceeded this threshold.

Across all provinces, only the districts of Chitral (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, 12.7%) and Shadadkot (Sindh, 9.9%), had active trachoma (TF and/or TI) prevalence in 1–9-year-olds of ≥5%. Access to clean water was noted to be a major problem in almost all districts.Citation22Citation22The aim of the present work was to (1) estimate the prevalence of TF among children aged 1–9 years and of trichiasis among persons aged ≥15 years, and (2) determine the proportion of households with access to improved water and sanitation facilities, in selected areas of Pakistan. This formed part of the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP).Citation23 This information was needed to direct trachoma elimination efforts at national, provincial and sub-district levels.

Methods

Prior to this series of surveys, as mentioned above, trachoma surveys had been completed in 38 districts of Pakistan. The work described here was considered a fourth phase of surveys. It was completed in 2015 and was intended by the National Trachoma Task Force to complete baseline surveys in suspected-endemic areas which did not then have valid prevalence data. Such suspected-endemic-but-unmapped areas were found across 29 districts, incorporating an estimated total population of 40,720,310. Due to time limitations and insecurity in some areas, 14 of the 29 districts were excluded from the plan. In the remaining 15 districts, we deprioritized urban areas (where risk of trachoma is considerably lowerCitation24), and constructed rural evaluation units (EUs) of approximately 200,000–300,000 people, as a compromise between the WHO-recommendedCitation25 100,000–250,000-person EU size, and the relatively low perceived likelihood of identifying populations here in which trachoma was a public health problem. (A similar compromise has been reached elsewhere.Citation26,Citation27) This produced a total of 43 EUs (). In each of these, a separate EU-level survey was planned and commenced. (In one EU, however, insecurity prevented completion.)

Table 1. Districts in which baseline trachoma prevalence surveys were commenced, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Pakistan, October–December 2015.

Following standard GTMP approaches,Citation28,Citation29 a two-stage cluster sampling method was used to determine which villages and households would be included in each survey. In each EU, 26 villages were randomly selected. Within each of those villages, a compact segment of 30 households was randomly selected and residents of those 30 households aged ≥1 year were enumerated and invited to participate.

Field team structure and training

In Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, each survey team was composed of one female grader, one male grader, one female recorder and one male recorder. In these provinces, for cultural reasons, female and male team members were unable to access male and female sections of the household, respectively, or examine household residents of the opposite gender. Each team had a driver and was accompanied by a local village guide. In Sindh, Punjab, Azad Jammu & Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan, each survey team was composed of one grader and one recorder, with one driver for every 1–2 teams, depending on the geography of deployment; as in Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, each team was accompanied by a local village guide. Ophthalmologists supervised the teams.

Extensive searches around Faisalabad for trachoma-endemic localities in which to undertake field-based grader training and testing resulted in very few cases of active trachoma being identified, and it was resolved instead to undertake this process in Sokoto, Nigeria, where a number of local government areas still had TF prevalences of 5.0–9.9%.Citation30 In August 2015, a total of 23 grader trainees went to Sokoto; 16 passed the inter-grader agreement tests and were certified to participate in the surveys.Citation28 Three recorder trainers were also trained in Sokoto; they later conducted workshops in Pakistan to train 26 recorders. Version 2 of the GTMP training packageCitation31 was used. This included the use of questions about previous trichiasis management being asked of survey subjects found to have trichiasis,Citation32 but not recording of the presence or absence of trachomatous conjunctival scarring (TS)Citation9 in eyes diagnosed with trichiasis.Citation33 The latter element (recording of the presence or absence of TS) was introduced half-way through the surveys, in the form of Version 3 of the GTMP system; this was introduced to field team members via a specific training session.Citation34 TS data are therefore only available for the last 19 EUs mapped.

Fieldwork

Field teams liaised with district health authorities to find selected villages. Teams then created maps to plan survey routes. Schedules were communicated to the programme officer and supervisors on a weekly basis, to facilitate support.

Once in the field, given potential security concerns, particular emphasis was given to gaining district-, community-, household- and individual-level consent for the survey. The ophthalmologist led community-level engagement. The voluntary nature of participation by community residents was emphasized to communities throughout the survey process. Explicit consent from heads of households was required before field teams entered any household. Official government mission documents, identity cards, up-to-date points of contact and escalation channels were carried by field teams at all times.

All adults and children aged ≥1 year and residents in selected households were registered and asked to consent to eye examination. Grading was undertaken under 2.5× magnification, and the presence or absence of trichiasis, TF and TI recorded, using standard WHO simplified trachoma grading system definitions.Citation9 When an eye was diagnosed as having trichiasis, the subject was asked whether a health worker had previously recommended surgery or epilation; for (only) the last 19 EUs, in addition, the presence or absence of TS in that eye was recorded.

Data were collected electronically using LINKS/GTMP software based on Open Data Kit, running on the Android operating system.Citation28,Citation35 Teams moved from one household to the next. Data collected in the field were encrypted and securely transferred to a central data hosting, management, approval, and reporting system, where they were rapidly analysed, as previously described.Citation28

Graders used disposable latex gloves or cleaned their hands with 70% alcohol after each examination to avoid spreading infection. Basic treatment, such as 1% tetracycline eye ointment or analgesics, were provided on the spot to those in need. Patients requiring referral to hospital, including those with trichiasis, were promptly referred.

Analysis

Standard GTMP approachesCitation28,Citation29 were used for data cleaning, analysis, health ministry review, and approval. In the first 23 completed EUs, lacking information on the presence or absence of TS in eyes with trichiasis, we calculated the prevalence of “any trichiasis”; for the last 19 completed EUs, we calculated the prevalence of both any trichiasis and “trichiasis+TS”, defined here as the presence of both trichiasis and TS (or the inability of the examiner to evert the lid to look for TS, presumed to be due to dense scarring) in the same eye.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was given by the National Committee of Eye Health (1349/15) and the ethics committee of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (6319 and 8355). For many districts, non-objection certificates were also obtained from the relevant District Health Authority. Because of low levels of literacy in the target population, field teams obtained consent from prospective participants verbally. Consent for individuals aged <15 years was given by a parent or guardian. Individuals with trachoma or other medical problems that were diagnosed by the field team were treated or referred (using a formal, specifically designed referral slip), as appropriate.

Results

Fieldwork was undertaken from October to December 2015. Insecurity prevented completion of mapping in one EU; the incomplete data have been excluded from this presentation. The mean number of children examined per household varied considerably from one EU to another. In some EUs, recruitment of children in the initially-selected 26 villages yielded low numbers of 1–9-year-olds examined: in one case, this number was 558. Extra villages were selected (at random, using the original list of villages in the EU) in these EUs to compensate for the unexpectedly small household size. In some EUs, when mean household-level GPS co-ordinates were plotted by village, there was a clear overlap between the previously planned sub-Tehsil-level EUs. Borders for each EU occasionally needed to be adjusted for survey purposes (with the creation of new shapefiles), resulting in uneven numbers of villages sampled ().

Table 2. Number of 1–9-year-olds and number of ≥15-year-olds resident, examined, absent and refused; prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF), and prevalence of trichiasis (and, where possible, trichiasis+TS, see text) unknown to the health system, by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Pakistan, October–December 2015.

In all, a total of 33,432 households were visited in 1119 clusters across 42 EUs. Those households were home to 56,345 1–9-year-olds and 96,268 ≥ 15-year-olds.

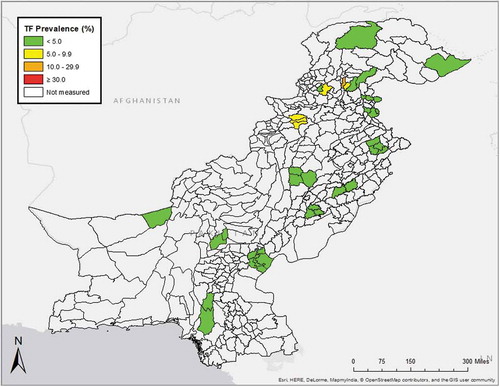

Of the 56,345 enumerated 1–9-year-olds, 54,334 (96%) consented and were examined, 1669 (3%) were absent on the day of the visit, 338 (1%) refused consent and 4 were not examined for other reasons. A mean of 1294 1–9-year-olds was examined per EU (range 768–2243). As shown in , the age-adjusted EU-level TF prevalence in 1–9-year-olds ranged from 0% in the EU covering Dhirkot, Bagh and Hari Ghal, to 13.6% (95%CI 9.3–18.3) in FR Kala Dhaka. Six (14%) of 42 EUs had age-adjusted TF prevalence estimates of ≥5% (, ).

Figure 1. Evaluation-unit-level prevalence of trachomatous inflammation—follicular (TF), adjusted for age (see text), Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Pakistan, October–December 2015.

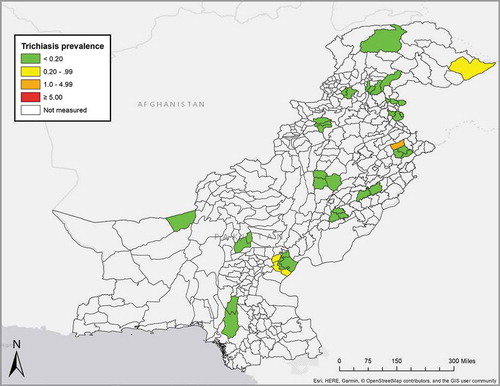

Of 96,268 enumerated ≥15-year-olds, 85,832 (89%) were examined, 8775 (9%) were absent on the day of the visit, 1648 (2%) did not agree to participate and 13 were not examined for other reasons (). The age- and gender-adjusted trichiasis prevalence in ≥15-year-olds (regardless of the presence or absence of TS) ranged from 0% to 2.96%. Twenty-two (52%) of 42 EUs had age- and gender-adjusted trichiasis prevalence estimates of 0%, 16 (38%) had non-zero trichiasis prevalence estimates that were less than the elimination threshold of 0.2%,Citation17 and four (10%) had trichiasis prevalence estimates of ≥0.2% in adults (, ). In only one EU (Ghotki Taluka, Khangarh Taluka) was the adjusted prevalence of trichiasis+TS substantially different from the adjusted prevalence of trichiasis ().

Figure 2. Evaluation unit (EU)-level prevalence of trichiasis unknown to the health system in ≥15-year-olds, adjusted for gender and age (see text), Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Pakistan, October–December 2015.

Household-level access to an improved source of water for face and hand washing ranged from 37% in the EU covering Chattar Sub-Tehsil and Dera Murad Jamali Tehsil, to 100% in 22 (52%) of the 42 EUs surveyed. In 36 (86% of) EUs, ≥80% of households had access to an improved source of water for face and hand washing ().

Table 3. Household-level access to water and sanitation, by evaluation unit, Global Trachoma Mapping Project, Pakistan, October–December 2015.

The proportion of households with access to an (improved or unimproved) source of water for face and hand washing within 1 km of the house ranged from 57% in the EU covering Sehwan Taluka to 100% in 19 (45%) of the 42 EUs surveyed. In 40 (95%) of the 42 EUs surveyed, ≥80% of households had access to a source of water for face and hand washing within 1 km of the house ().

Household-level access to improved sanitation ranged from a low of 6% in Genchi to a high of 100% in 4 (10%) of 42 EUs. In 23 (55%) of the EUs, ≥80% of households had access to improved sanitation ().

Discussion

Data from this fourth phase of baseline mapping represent another important step towards complete categorization of the distribution and burden of trachoma in Pakistan. Only three of 42 EUs mapped were shown to qualify for public-health-level deployment of trichiasis surgical services, and only six EUs (all in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) were shown to qualify for intervention with A, F, and E components of SAFE.Citation36 There was no overlap between the group of three EUs qualifying for S and the group of six EUs qualifying for A, F, and E. The very high prevalence of trichiasis in Wazirabad Tehsil 1 (2.96%, 95%CI 0.71–5.76) was unexpected and therefore requires confirmation, likely through a repeat survey. Low prevalences of active trachoma in the 19 EUs we surveyed in Punjab match the low prevalence of active disease recorded in children of Dera Ghazi Khan district, Punjab, by other investigators, in 2014.Citation37

Experience elsewhere suggests that SAFE strategy implementation would have a good chance of successfully eliminating trachoma here.Citation38–Citation40 Unfortunately, the recent outbreak of extensively drug-resistant typhoid in PakistanCitation41,Citation42 may prevent the national trachoma programme from using azithromycin mass drug administration, the SAFE strategy intervention with the strongest evidence for effect.Citation43 For EUs with TF prevalence estimates ≥5%, use of topical tetracycline eye ointment might be an option, though compliance with the prolonged course of treatment required could be anticipated to be lowCitation44, particularly amongst the large numbers of asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic individuals who would be offered it in a mass treatment campaign. Intensive implementation of the F and E components of the SAFE strategyCitation45,Citation46 could be another solution. We note that the prevalence of household-level access to water and sanitation varied markedly between EUs (), though several of the EUs with TF prevalence ≥5% already had levels of access to these services that associate with lower risk of (and even, for sanitation coverage ≥80%, “herd protection” against) active trachoma.Citation47,Citation48 We also note that the evidence base for the F and E interventions is weak.Citation49–Citation51

Not all trichiasis is caused by trachoma.Citation52 Pakistan was one of the first GTMP deployments in which we were able to explore the effect of separating out trichiasis seen in association with TS from trichiasis noted in its absence. Guided by the Second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachomatous Trichiasis,Citation33 half-way through this series of surveys, we asked field teams to start recording whether or not scarring was clearly visible in the conjunctivae of eyes with trichiasis; where they were unable to evert the eyelid to check, TS was assumed to be present. In this low-prevalence setting, this would have made a difference to the categorization of EUs as requiring or not requiring public health-level “S” interventions in only one instance. Further work to better understand the epidemiology, phenotypes and vision-threatening potential of trichiasis with and without visible scar is needed.Citation53

Building on results from the GTMP in Pakistan and elsewhere,Citation54 momentum towards global elimination of trachoma is progressively building.Citation55–Citation57 In April 2018, in London, Commonwealth Heads of Government pledged their commitment to the global targetCitation58 and the United Kingdom re-affirmed financial support.Citation59 It is recommended that stakeholders in Pakistan take advantage of these developments, rapidly complete planning using the data presented here, and implement a national programme that can bring about trachoma elimination nationwide.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Feasey N, Wansbrough-Jones M, Mabey DC, Solomon AW. Neglected tropical diseases. Br Med Bull. 2010;93:179–200. doi:10.1093/bmb/ldp046.

- Bourne RR, Stevens GA, White RA, et al. Causes of vision loss worldwide, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(6):e339–49. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(13)70113-X.

- Caldwell HD, Wood H, Crane D, et al. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiate between genital and ocular isolates. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(11):1757–1769. doi:10.1172/JCI17993.

- Hadfield J, Harris SR, Seth-Smith HMB, et al. Comprehensive global genome dynamics of Chlamydia trachomatis show ancient diversification followed by contemporary mixing and recent lineage expansion. Genome Res. 2017;27(7):1220–1229.doi:10.1101/gr.212647.116.

- Gambhir M, Basanez MG, Burton MJ, et al. The development of an age-structured model for trachoma transmission dynamics, pathogenesis and control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3(6):e462. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000462.

- Munoz B, Bobo L, Mkocha H, Lynch M, Hsieh YH, West S. Incidence of trichiasis in a cohort of women with and without scarring. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28(6):1167–1171. doi:10.1093/ije/28.6.1167.

- Bowman RJ, Jatta B, Cham B, et al. Natural history of trachomatous scarring in The Gambia: results of a 12-year longitudinal follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(12):2219–2224. doi:10.1016/S0161-6420(01)00645-5.

- Courtright P, Sheppard J, Schachter J, Said ME, Dawson CR. Trachoma and blindness in the Nile Delta: current patterns and projections for the future in the rural Egyptian population. Br J Ophthalmol. 1989;73(7):536–540. doi:10.1136/bjo.73.7.536.

- Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR, West SK, Taylor HR. A simple system for the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World Health Organ. 1987;65:477–483.

- Palmer SL, Winskell K, Patterson AE, et al. ‘A living death’: a qualitative assessment of quality of life among women with trichiasis in rural Niger. Int Health. 2014;6(4):291–297. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihu054.

- Burton MJ, Bowman RJ, Faal H, et al. The long-term natural history of trachomatous trichiasis in the Gambia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):847–852. doi:10.1167/iovs.05-0714.

- World Health Assembly. Global elimination of blinding trachoma. 51st World Health Assembly, Geneva, 16 May 1998, Resolution WHA51.11. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998.

- Francis V, Turner V. Achieving Community Support for Trachoma Control (WHO/PBL/93.36). Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993.

- Kuper H, Solomon AW, Buchan J, Zondervan M, Foster A, Mabey D. A critical review of the SAFE strategy for the prevention of blinding trachoma. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(6):372–381. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00659-5.

- Solomon AW, Peeling RW, Foster A, Mabey DC. Diagnosis and assessment of trachoma. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(4):982–1011. doi:10.1128/CMR.17.4.982-1011.2004.

- Smith JL, Sturrock HJ, Olives C, Solomon AW, Brooker SJ. Comparing the performance of cluster random sampling and integrated threshold mapping for targeting trachoma control, using computer simulation. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2389. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002389.

- World Health Organization. Validation of elimination of trachoma as a public health problem (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.8). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Alimuddin M. Incidence and treatment of trachoma in Pakistan. Br J Ophthalmol. 1958;42(6):360–366. doi:10.1136/bjo.42.6.360.

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Provisional Summary Results of 6th Population and Housing Census, 2017 [Press Release]. Islamabad: Government of Pakistan; 2017 http://www.pbscensus.gov.pk/sites/default/files/Population_Results.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2017.

- Negrel AD, Taylor HR, West S. Guidelines for Rapid Assessment for Blinding Trachoma (WHO/PBD/GET/00.8). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- National Task Force on Trachoma. Report on Trachoma Rapid Assessment in Pakistan. Islamabad: Ministry of Health; 2004.

- Jadoon MZ. Report on National Trachoma Survey, 2011–2013. Islamabad: National Committee for Eye Health, Pakistan/The Fred Hollows Foundation; 2013.

- Solomon AW, Kurylo E. The global trachoma mapping project. Community Eye Health. 2014;27:18.

- Smith JL, Sivasubramaniam S, Rabiu MM, Kyari F, Solomon AW, Gilbert C. Multilevel analysis of trachomatous trichiasis and corneal opacity in Nigeria: the role of environmental and climatic risk factors on the distribution of disease. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9(7):e0003826. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003826.

- World Health Organization. Report of the 3rd Global Scientific Meeting on Trachoma, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MA, 19-20 July 2010 (WHO/PBD/2.10). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

- Southisombath K, Sisalermsak S, Chansan P, et al. National trachoma assessment in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic in 2013–2014. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):8–14. doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1236973.

- Meng N, Seiha D, Thorn P, et al. Assessment of trachoma in Cambodia: trachoma is not a public health problem. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(sup1):3–7.doi:10.1080/09286586.2016.1230223.

- Solomon AW, Pavluck A, Courtright P, et al. The Global Trachoma Mapping Project: methodology of a 34-country population-based study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):214–225. doi:10.3109/09286586.2015.1037401.

- Solomon AW, Willis R, Pavluck AL, et al. Quality assurance and quality control in the global trachoma mapping project. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;99(4):858–863. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.18-0082.

- Mpyet C, Muhammad N, Adamu MD, et al. Impact survey results after SAFE strategy implementation in fifteen Local Government Areas of Kebbi, Sokoto and Zamfara States, Nigeria. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(sup1):103–114. doi:10.1080/09286586.2018.1481984.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: Training for Mapping of Trachoma (Version 2). London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2013. http://www.trachomacoalition.org/node/357.

- Hiep NX, Ngondi JM, Anh VT, et al. Trachoma in Viet Nam: results of 11 surveillance surveys conducted with the Global Trachoma Mapping Project. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2018;25(sup1):93–102. doi:10.1080/09286586.2018.1477964.

- World Health Organization Alliance for the Global Elimination of Trachoma by 2020. Second Global Scientific Meeting on Trachomatous Trichiasis. Cape Town, 4–6 November 2015 (WHO/HTM/NTD/2016.5). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

- Courtright P, Gass K, Lewallen S, et al. Global Trachoma Mapping Project: Training for Mapping of Trachoma (Version 3). London: International Coalition for Trachoma Control; 2014. http://www.trachomacoalition.org/node/122

- Pavluck A, Chu B, Mann Flueckiger R, Ottesen E. Electronic data capture tools for global health programs: evolution of LINKS, an Android-, web-based system. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2014;8(4):e2654. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002654.

- Solomon AW, Zondervan M, Kuper H, Buchan JC, Mabey DCW, Foster A. Trachoma Control: A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

- Khokhar AR, Sabar S, Lateef N. Active trachoma among children of District Dera Ghazi Khan, Punjab, Pakistan: a cross sectional study. J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:1300–1303.

- Ngondi J, Onsarigo A, Matthews F, et al. Effect of 3 years of SAFE (surgery, antibiotics, facial cleanliness, and environmental change) strategy for trachoma control in southern Sudan: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2006;368(9535):589–595. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69202-7.

- Hammou J, El Ajaroumi H, Hasbi H, Hmadna A, El Maaroufi A. In Morocco, the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem becomes a reality. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(3):e250–e1. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30023-2.

- Kalua K, Chisambi A, Chainyanya D, et al. One round of azithromycin MDA adequate to interrupt transmission in districts with prevalence of trachomatous inflammation-follicular of 5.0-9.9%: evidence from Malawi. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(6):e0006543.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006543.

- Klemm EJ, Shakoor S, Page AJ, et al. Emergence of an extensively drug-resistant Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi clone harboring a promiscuous plasmid encoding resistance to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins. mBio. 2018;9(1):e00105–18.doi:10.1128/mBio.00105-18.

- Cohen J. ‘Frightening’ drug-resistant strain of typhoid spreads in Pakistan. Science. 2018;361(6399):214. doi:10.1126/science.361.6399.214.

- Evans JR, Solomon AW. Antibiotics for trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;3:CD001860. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001860.pub3.

- Bowman RJ, Sillah A, Van Dehn C, et al. Operational comparison of single-dose azithromycin and topical tetracycline for trachoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(13):4074–4079.

- West S, Munoz B, Lynch M, et al. Impact of face-washing on trachoma in Kongwa, Tanzania. Lancet. 1995;345(8943):155–158. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(95)90167-1.

- Emerson PM, Lindsay SW, Alexander N, et al. Role of flies and provision of latrines in trachoma control: cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363(9415):1093–1098. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15891-1.

- Oswald WE, Stewart AE, Kramer MR, et al. Active trachoma and community use of sanitation, Ethiopia. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(4):250–260.doi:10.2471/BLT.16.177758.

- Garn JV, Boisson S, Willis R, et al. Sanitation and water supply coverage thresholds associated with active trachoma: modeling cross-sectional data from 13 countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(1):e0006110.doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006110.

- Ejere HO, Alhassan MB, Rabiu M. Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD003659. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003659.pub4.

- Rabiu M, Alhassan MB, Ejere HO, Evans JR. Environmental sanitary interventions for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD004003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004003.pub4.

- Delea MG, Solomon H, Solomon AW, Freeman MC. Interventions to maximize facial cleanliness and achieve environmental improvement for trachoma elimination: a review of the grey literature. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12(1):e0006178. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0006178.

- World Health Organization Strategic and Technical Advisory Group on Neglected Tropical Diseases. Technical consultation on trachoma surveillance. September 11−12, 2014, Task Force for Global Health, Decatur, USA (WHO/HTM/NTD/2015.02). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- Solomon AW, Bella AL, Negussu N, Willis R, Taylor HR. How much trachomatous trichiasis is there? A guide to calculating district-level estimates. Community Eye Health. 2019;31:55–58.

- Mpyet C, Kello AB, Solomon AW. Global elimination of trachoma by 2020: a work in progress. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2015;22(3):148–150. doi:10.3109/09286586.2015.1045987.

- World Health Organization. WHO alliance for the global elimination of Trachoma by 2020: progress report on elimination of trachoma, 2014–2016. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(26): 359–368.

- Solomon AW, Emerson PM, Resnikoff S. Trachoma then and now: update on mapping and control. Community Eye Health. 2017;30:90–91.

- Courtright P, Rotondo LA, MacArthur C, et al. Strengthening the links between mapping, planning and global engagement for disease elimination: lessons learnt from trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(10):1324–1327.doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312476.

- The Commonwealth. Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting. Communiqué: Towards a Common Future. London: The Commonwealth; 2018.

- Department for International Development. UK aid to help eliminate the world’s leading infectious cause of blindness across poorest countries in the Commonwealth by 2020. [press release, 16 April 2018]; 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-aid-to-help-eliminate-the-worlds-leading-infectious-cause-of-blindness-across-poorest-countries-in-the-commonwealth-by-2020? Accessed April, 29 2018.

Appendix

The Global Trachoma Mapping Project Investigators are: Agatha Aboe (1,11), Liknaw Adamu (4), Wondu Alemayehu (4,5), Menbere Alemu (4), Neal D. E. Alexander (9), Ana Bakhtiari (2,9), Berhanu Bero (4), Sarah Bovill (8), Simon J. Brooker (1,6), Simon Bush (7,8), Brian K. Chu (2,9), Paul Courtright (1,3,4,7,11), Michael Dejene (3), Paul M. Emerson (1,6,7), Rebecca M. Flueckiger (2), Allen Foster (1,7), Solomon Gadisa (4), Katherine Gass (6,9), Teshome Gebre (4), Zelalem Habtamu (4), Danny Haddad (1,6,7,8), Erik Harvey (1,6,10), Dominic Haslam (8), Khumbo Kalua (5), Amir B. Kello (4,5), Jonathan D. King (6,10,11), Richard Le Mesurier (4,7), Susan Lewallen (4,11), Thomas M. Lietman (10), Chad MacArthur (6,11), Colin Macleod (3,9), Silvio P. Mariotti (7,11), Anna Massey (8), Els Mathieu (6,11), Siobhain McCullagh (8), Addis Mekasha (4), Tom Millar (4,8), Caleb Mpyet (3,5), Beatriz Muñoz (6,9), Jeremiah Ngondi (1,3,6,11), Stephanie Ogden (6), Alex Pavluck (2,4,10), Joseph Pearce (10), Serge Resnikoff (1), Virginia Sarah (4), Boubacar Sarr (5), Alemayehu Sisay (4), Jennifer L. Smith (11), Anthony W. Solomon (1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11), Jo Thomson (4); Sheila K. West (1,10,11), Rebecca Willis (2,9).

1. Advisory Committee, 2. Information Technology, Geographical Information Systems, and Data Processing, 3. Epidemiological Support, 4. Ethiopia Pilot Team, 5. Master Grader Trainers, 6. Methodologies Working Group, 7. Prioritisation Working Group, 8. Proposal Development, Finances and Logistics, 9. Statistics and Data Analysis, 10. Tools Working Group, 11. Training Working Group.