ABSTRACT

Purpose

Diabetic retinopathy is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. In the United States, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy is 26% – 33%. Providing preventive care to individuals with diabetes is important to prevent microvascular complications in the eye. This study reports on the results of a randomized controlled trial to determine how using specific cues to action combined with the provision of a free eye exam might positively influence the rate of diabetic retinopathy screening among individuals with diabetes.

Methods

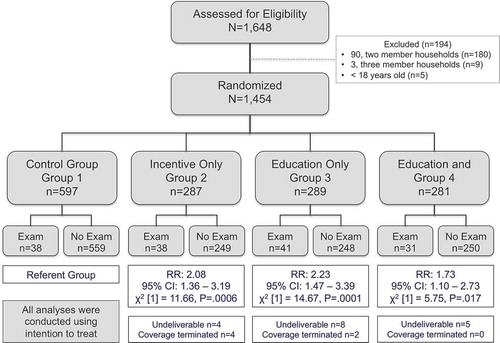

Individuals were eligible to participate in this campaign if they had a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes or were prescribed a diabetes drug, were members of the health insurance plan during the intervention period and had no evidence of receiving a retinal eye exam prior to the campaign period. The six-week campaign period started on September 19, 2017 and ended on October 31, 2017. A total of 1,454 individuals with type 2 diabetes were randomly assigned to a control group or to one of three intervention groups. Each intervention group included the provision of a free eye exam.

Results

A total of 148 (10.1%) individuals obtained a retinal eye exam during the six-week campaign period with 38 persons (6.8%) in the control group, 38 (15.3%) in the incentive group, 41 (16.5%) in the education group, and 31 (12.4%) in the incentive and education group. Individual intervention comparisons with the referent group yielded statistical significance using the adjusted pairwise alpha of P = .008 for the incentive group (RR = 2.08; 95% CI, 1.36–3.19; P =.0006) and for the education group (RR = 2.23; 95% CI, 1.47–3.39; P =.0001), but not in the incentive plus education group (RR = 1.73; 95% CI, 1.10–2.73; P =.017).

Conclusion

This study supports the use of targeted cues to action combined with the provision of a free eye exam to increase the rates of diabetic retinopathy screening among individuals with diabetes who have health insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act in a Central Texas population.

Introduction

Diabetes is a global health problem. The World Health Organization estimates that 422 million adults worldwide have diabetes, with the vast majority (90%) having type 2 diabetes mellitus.Citation1 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that 30.2 million American adults have diabetes with an additional 84.1 million, or 33.9% of the population (aged ≥18 years), diagnosed with prediabetes.Citation2 Diabetes is ranked as the seventh leading cause of death in the US.Citation2 Diabetes-related comorbid conditions include both micro- and macrovascular complications. Among the former are diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy, while the latter includes peripheral artery disease, coronary artery disease, and stroke.

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of preventable blindness in the world.Citation3 A cross-sectional analysis of patients in Sweden reported a diabetic retinopathy prevalence rate of 12.7% among type 2 diabetic patients.Citation4 Studies in the US report diabetic retinopathy prevalence rates ranging from 26% to 33%.Citation5,Citation6

In an effort to reduce vision loss and blindness associated with diabetes, we conducted a multi-armed randomized controlled trial designed to assess member uptake of the annual retinal eye examination for individuals with diabetes who have health insurance from a community-based health insurance company. Four groups were randomized: (1) a control group with no intervention; (2) a monetary incentive group that received a 25 USD gift card after the exam was completed; (3) a patient education only group; and (4) a group that received both patient education and a 25 USD gift card after completion of the examination. The three intervention groups also received a free eye exam. The objective of this study was to determine if the use of single or multiple cues to action combined with the provision of a free eye care exam could positively influence the rates of retinal eye examination by individuals with diabetes.

This study received Institutional Review Board approval. (Aspire Institutional Review Board approval on July 13, 2017 for protocol 2016 F-09-05.) This study was deemed minimal risk by the IRB and the request of HIPAA Waiver of Authorization for informed consent for recruitment was reviewed and approved. The completed CONSORT checklist for this randomized controlled trial is available for review.

Materials and methods

Members were eligible to participate in this study if they had a medical claim for type 2 diabetes or a pharmacy claim for a medication used to treat type 2 diabetes during the period January 1 through June 30, 2017. (See for eligibility specifications.) Excluding individuals who had already obtained a retinal eye exam through June 30, 2017 and members who had ongoing, active management for ocular complications associated with diabetes mellitus, 1,648 individuals were identified. Individuals less than 18 years of age and individuals who did not reside in a single member household, were excluded, leaving a sample size of 1,454 individuals (see ). Single-member households were chosen as the unit of analysis to prevent cross-contamination among additional household members who may have type 2 diabetes, but who may have been assigned to a different intervention group or to the control group. No changes to eligibility criteria occurred after the trial commenced. The available study population allowed for a 2:1:1:1 allocation with a minimum intervention group size of 100 assuming α = 0.05 and a pre-specified power of 0.8 and effect size of 0.5. The four trial arms included:

Group 1 (Controls): Individuals in this arm were passively observed to see if they obtained a retinal eye exam. This group is identified as the referent group for subsequent inferential analyses. No contact was provided to persons in this group with regard to this study.

Group 2 (Incentive Only): Individuals in this arm were sent a one-page mailer inviting them to visit an eye care specialist to be screened for diabetic retinopathy. They were offered a 25 USD gift card upon completion of the retinal eye exam, and they were provided a Sendero Eye Care Provider Directory. Individuals in this group were provided the retinal eye exam at no charge.

Group 3 (Education Only): Individuals in this arm were sent a one-page mailer inviting them to visit an eye care specialist to be screened for diabetic retinopathy. A fact sheet on microvascular complications associated with diabetes was enclosed. Also enclosed was a checklist of essential tests for people with type 2 diabetes. This checklist included the test name, the frequency in which it should be obtained, and a place to record the date of the test and its results. Individuals in this group were provided a Sendero Eye Care Provider Directory. Individuals in this group were provided the retinal eye exam at no charge.

Group 4 (Incentive plus Education): Individuals in this arm were sent a one-page mailer inviting them to visit an eye care specialist to screen for diabetic retinopathy. They were offered a 25 USD gift card upon completion of the retinal eye exam. A fact sheet, checklist, and eye care directory were enclosed (as described for Group 3 above). Individuals in this group were provided the retinal eye exam at no charge.

Table 1. Eligibility for the Sendero Health Plan 2017 retinal eye exam campaign for members with type 2 diabetes.

A three-step process was used to randomly allocate individuals to each of the four trial arms.

Randomly assign each of the 1,454 eligible participants a number from 1 to 5. This assignment was completed with a random number generator.

Randomly assign each of the four trial arms a number from 1 to 5. This assignment was completed with a random number generator. The control group was assigned two of the five numbers because the power analysis calculation indicated that the control group should have at least twice the number of participants as each of the intervention groups. The control group was randomly assigned numbers 1 and 4; the incentive only group was randomly assigned number 5; the education group was randomly assigned number 3; and the intervention plus education group was randomly assigned number 2.

Match participants to one of the four trial arms based on the randomly assigned matching number of 1 to 5.

The research intern, under the direction of the principal investigator, was responsible for the random allocation sequence. Participants were enrolled by sending them information on their assigned intervention.

Through this randomization process, 597 members were assigned to the control group (1), 287 were assigned to the incentive only group (2), 289 were assigned to the education only group (3), and 281 were assigned to the incentive plus education group (4). Seventeen members in the three intervention groups were lost to follow-up due to a change of address without notifying Sendero. An additional six people had their coverage terminated post randomization. Data analysis was based on intention to treat. summarizes the randomization process, lost to follow-up, and coverage termination for this study.

Member demographic data and medical claims data were used for analysis. The primary outcome of interest was receipt of a retinal eye exam during the six-week campaign. Members who obtained a retinal eye exam from either an ophthalmologist or optometrist were deemed to have completed a retinal eye exam based solely on Common Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 92004, 92012, and 92014, in accordance with US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Quality Rating System technical specifications.Citation7 Non-eye care providers (i.e., providers without specialist training in eye care) must have also provided either a category two CPT code or a Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code to indicate retinal examination occurred (see ). Data for this clinical trial were collected and analyzed at Sendero Health Plans based on electronic submission of a medical claim by individual providers.

Table 2. Demographic variables and codes used for statistical analyses.

CPT claims status was based on a date of claim that occurred from September 19, 2017 through October 31, 2017 (the study period). Providers may take up to 90 days to submit a claim after the date of service. In accordance with end of year activities, we ran a SQL query after March 31, 2018 to confidently account for all claims that may have occurred during the study period. This would have allowed providers to meet the 90-day claim submission deadline and to account for any additional delayed claims.

Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25 for Macintosh) and Microsoft Excel® (Version 16.19 for Macintosh). Member demographic data were obtained from the centralized Sendero member database and member encounter data were obtained from the Sendero claims database. Data from these two sources were merged using de-identified, unique identification numbers.

The Pearson chi-square test of independence was used to evaluate whether providing an intervention at all was associated with a member’s decision to obtain a retinal eye exam. Additional post-hoc analyses were used to evaluate which specific intervention, if any, was associated with the member’s decision to obtain a retinal eye exam. The group comparison was deemed to be significant at α = 0.05 while the individual pairwise comparisons were deemed to be significant using an adjusted α = 0.008 to control for the possibility of familywise error. The adjusted alpha is determined by dividing α = 0.05 by the number of pairwise comparisons, which in this study was six. Additionally, relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated to compare each intervention group to the control group (referent) to assess the magnitude of the association. The corresponding P values were obtained using the Pearson chi-square test of independence.

Results

A total of 148 (10.1%) individuals obtained a retinal eye exam during the six-week study period. Of these individuals, 38 (6.8%) were in the control group (1), 38 (15.3%) were in the incentive group (2), 41 (16.5%) were in the education group (3), and 31 (12.4%) were in the incentive and education group (4). (See .) The attributable risk for the three intervention arms was 50.4%. The overall chi-square test of independence was statistically significant (χ2 [3] = 17.74; P < .001), suggesting a relationship between a member’s decision to obtain a retinal eye exam and receiving any one of the interventions.

Table 3. Demographic variables of diabetic members who were assigned to and who obtained a retinal eye exam between September 17, 2017 and October 31, 2017.

Table 4. Number and percent of diabetic members who were assigned to and who obtained a retinal eye exam between September 17, 2017 and October 31, 2017.

Pairwise comparisons with the adjusted α = .008 using the control group as the referent group yielded statistical significance for both the incentive group (RR = 2.08; 95% CI, 1.36–3.19; P = .0006) and the education group (RR = 2.23; 95% CI, 1.47–3.39; P = .0001). However, a pairwise comparison between the referent group and the incentive plus education group did not yield statistical significance at the adjusted alpha (RR = 1.73; 95% CI, 1.10–2.73; P = .017). (See .) Additionally, our data did not suggest a significant difference in retinal eye exam uptake between the education group and the incentive group (RR = 1.07; 95% CI, .71–1.61; P = .74).

The mean [SD] age of study participants who obtained a retinal eye exam was 56.42 [9.29] years (range, 27–83 years). There was no statistical difference in age across the four groups (χ2 [3] = 2.67; P = .44). The number of females who obtained a retinal eye exam were even to or higher than the number of males who obtained a retinal eye exam across all groups, ranging from 50.0% in the control group (1) to a high of 65.9% in the education group (3) (See ).

The majority of persons who obtained a retinal eye exam resided in Travis County (n = 80; 54.1%), followed by Williamson County (n = 48; 32.4%). Of the 148 individuals who obtained a retinal eye exam, 70 (47.3%) obtained the exam from an ophthalmologist and 52 (35.1%) obtained the exam from an optometrist. The majority of individuals who obtained a retinal eye exam fell within 100%–250% of the US federal poverty level (n = 104; 70.3%).

Discussion

Results from our study show that using targeted cues to action (education only, incentive only, or a combination of both) and a free eye exam increased the rates of retinal eye examination uptake among individuals with diabetes. The results from our study are also consistent with other reported findings that show patient education and patient reminders play a positive role in encouraging individuals with type 2 diabetes to obtain an annual retinal eye examination.Citation8–Citation10 Likewise, our study is consistent with research and opinion that indicate incentives have a positive impact on improving the uptake of health services.Citation11

However, with our findings come several points of discussion about using a financial incentive. The first issue is disquiet among some who may believe that using a financial incentive is equivalent to ‘paying’ a person to receive a health benefit and the second is the long-term viability of providing such an incentive, particularly among a large managed care population. We provide our insight into these two issues from the health insurance company perspective.

We do not believe it is inappropriate to provide a financial incentive to encourage a positive health behavior per se; rather, we view an incentive as an opportunity to maximize utility for both the member and the health insurance plan.Citation12 For the member, utility is maximized by the potential to achieve optimal health, which in this case is to identify, prevent, or mitigate diabetic retinopathy and subsequent vision loss or blindness. For the health insurance company, utility is maximized by helping members manage their long-term health and by reducing expenditure associated with diabetic retinopathy. Indeed, studies have shown that the use of financial incentives can encourage an individual to engage in a healthy behavior.Citation13 When viewed as a form of trade, this voluntary action, if implemented, provides benefits to both parties. In addition, because participation is voluntary, a person may choose either to participate or not to participate. Indeed, 249 individuals chose not to participate in the incentive only arm of this study.

Secondly, there may be a concern about the long-term viability of offering financial incentives to members of a managed care population. This has both cost effectiveness and cost benefit considerations, where the former is defined as an “efficient use of (scarce) resources” and the latter is defined as a type of economic evaluation that “measures costs and benefits in monetary units and computes a net pecuniary gain/loss.”Citation14 From the health insurance company perspective, we believe that a reasonable financial incentive for a healthy behavior is both cost effective and has a net cost benefit to both the health insurance plan and to the individual. We explain why below.

Firstly, the Affordable Care Act requires a health insurance company to spend at least 80% of its revenue raised from premiums on medical claims and quality improvement activities.Citation15 The remaining 20% can be spent on administrative services, including salaries, overhead, and marketing costs. Companies that do not meet the minimum 80% spending requirement for medical claims and quality improvement activities must provide a rebate of the difference to those who purchased the health insurance policy. Therefore, a financial incentive tied to improved member health has the following benefits to a health insurance company: (1) an opportunity for improved member health; (2) an improved NCQA HEDIS quality measure score; and (3) the ability to encumber funds within the medical claims and quality improvement cost center. As such, we believe that the use of a financial incentive tied to a quality improvement activity, like providing an incentive for a retinal eye exam for diabetic members, is cost effective.

From a cost benefit perspective, data in the peer-reviewed literature show increased medical expenditure for an individual diagnosed with diabetic retinopathy as compared to an individual diagnosed with diabetes only. For example, on average, an additional 3,825 USD and 1,133 USD per person was expended in total medical claims and ophthalmic claims for a person with diabetic retinopathy as compared to a person with a diabetes-only diagnosis, respectively.Citation16 As such, preventing diabetic retinopathy, despite incurring a modest cost for the incentive, can have substantial savings in medical claims. The ultimate return on investment, however, lies with the individual policy holder as rate setting must account for likely expenditure during the upcoming year; therefore, any opportunity to reduce medical claim expenditure by incentivizing use of a preventive service, is ultimately reflected in future premiums. From an applied policy perspective, we do not necessarily favor the incentive approach over the education only approach. Rather, our discussion on financial incentives is to provide the reader with a perspective from a health insurer. We believe that financial incentives have a role – but not a singular role – in encouraging member uptake of a preventive screening exam.

For the pairwise comparison between the three different incentive groups, we note that the group that contained both the financial incentive and the education incentive had a lower rate of medical eye exam uptake than either of the other two incentive groups (incentive only or education only) when compared to the referent group. Our expectation was that using both cues to action (education and monetary incentive) would have had an additive or multiplicative effect on the outcome of interest. We hypothesize that information overload related to receiving too much material on both the financial and education incentives may have discouraged individuals randomized to this group from opening or reviewing the information. Additional studies are warranted to understand why multiple cues to action might have a lower rate of uptake than single cues to action.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Individuals in the three intervention groups (2–4) received their retinal eye exam at no cost, but individuals in the control group may have incurred a cost depending on their specific benefit package. We are unable to disentangle the effect of the interventions from the effect of providing a free eye exam on the uptake of the retinal exam, and suggest additional studies are needed to independently study the impact of a cue to action that offers a free retinal eye exam only on the rates of retinal eye exams in this population. A second limitation is the short six-week duration of the intervention period. The limited intervention period may have reduced uptake by individuals due to a lack of appointment times or scheduling issues with eye care providers. One of the goals of this study was to see if members would respond positively to messaging from their insurance provider to obtain needed medical services, even during a limited time period. The study results seem to support that members will respond positively to such messaging from their insurance provider. A third limitation is that this study was powered to detect whether a member’s decision to obtain a retinal eye exam was independent of whether or not they received a cue to action; it was not powered to detected differences related to specific variables like age, sex, or county of residence. Further studies are needed to determine if age, gender, or county of residence influences the decision of a member to uptake a retinal eye exam. A fourth limitation is that we do not know if individuals obtained their retinal eye exam outside of the Sendero provider network. If this is the case, then these study results are conservative.

Conclusion

Individuals with type 2 diabetes who received a cue to action with free eye care were more likely to obtain a retinal eye exam as compared to individuals in the control group who did not receive any contact with regard to this trial. Evidence from this study suggests that providing either a 25 USD monetary incentive or education materials along with free eye care is independently associated with retinal eye exam uptake, though rates are lower when using cues to action involving both a monetary incentive plus education material with free eye care.

Ackowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance and advice of current and former Sendero staff members and contractors Linda Burton, Norma Lozano, Rodolfo Ybarra, Priscilla Gonzales, Dr. Milton Thomas, and Dr. Avishek Kumar in the development of this project. The authors would also like to acknowledge Travis County taxpayer support of Sendero Health Plans.

Declaration of interest statement

Dr Litaker, Dr. Taylor, and Ms. Tamez are paid contractors to Sendero Health Plans. Mr. Durkalski is employed by Sendero Health Plans. Mr. Palma was formerly an intern with Sendero Health Plans. Funding for this project was provided in the form of staff and contractor time by Sendero Health Plans.

Institutional review board approval

This project received ethics approval by Aspire IRB on July 13, 2017, IRB Number: 2016F-09.

Registration

ISRCTN Registry

Registration Number: ISRCTN 87443551

Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Global Report On Diabetes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016:6. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed April 14, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017:2–7. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf. Accessed April 14, 2019.

- Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong T. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet. 2010;376(9735):124–136. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)62124-3.

- Gedebjerg A, Almdal T, Berencsi K, et al. Prevalence of micro- and macrovascular diabetes complications at time of type 2 diabetes diagnosis and associated clinical characteristics: A cross-sectional baseline study of 6958 patients in the Danish DD2 cohort. J Diabetes Complicat. 2018;32(1):34–40. doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.09.010.

- Wong T, Klein R, Islam F, et al. Diabetic retinopathy in a multi-ethnic cohort in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;141(3):446–455.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2005.08.063.

- Emanuele N, Sacks J, Klein R, et al. Ethnicity, race, and baseline retinopathy correlates in the veterans affairs diabetes trial. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):1954–1958. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.8.1954.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2017 Quality rating system measure technical specifications. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2016. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityInitiativesGenInfo/Downloads/2017_QRS-Measure_Technical_Specifications.pdf. Accessed March 6, 2019.

- Anderson R, Musch D, Nwankwo R, et al. Personalized follow-up increases return rate at urban eye disease screening clinics for African Americans with diabetes: results of a randomized trial. Ethnicity Dis. 2003;13(1):40–46. https://ethndis.org/priorarchives/ethn-13-01-40.pdf.

- Walker E, Schechter C, Caban A, Basch C. Telephone intervention to promote diabetic retinopathy screening Among the urban poor. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):185–191. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.020.

- Halbert R, Leung K, Nichol J, Legorreta A. Effect of multiple patient reminders in improving diabetic retinopathy screening. A randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(5):752–755. doi:10.2337/diacare.22.5.752.

- Oliver A. Can financial incentives improve health equity? BMJ. 2009;339(sep242):b3847–b3847. doi:10.1136/bmj.b3847.

- Grant R. The ethics of incentives: historical origins and contemporary understandings. Econ Philos. 2002;18(1):111–139. doi:10.1017/s0266267102001104.

- Wadge H, Bicknell C, Vlaev I. Perceived ethical acceptability of financial incentives to improve diabetic eye screening attendance. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2015;3(1):e000118. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2015-000118.

- Kobelt G. Health Economics. London: Office of health economics; 2002:120.

- Rate Review & the 80/20 Rule. HealthCare.gov. https://www.healthcare.gov/health-care-law-protections/rate-review/. Published 2019. Accessed December 7, 2019.

- Schmier J, Covert D, Lau E, Matthews G. Medicare expenditures associated with diabetes and diabetic retinopathy. Retina. 2009;29(2):199–206. doi:10.1097/iae.0b013e3181884f2d.