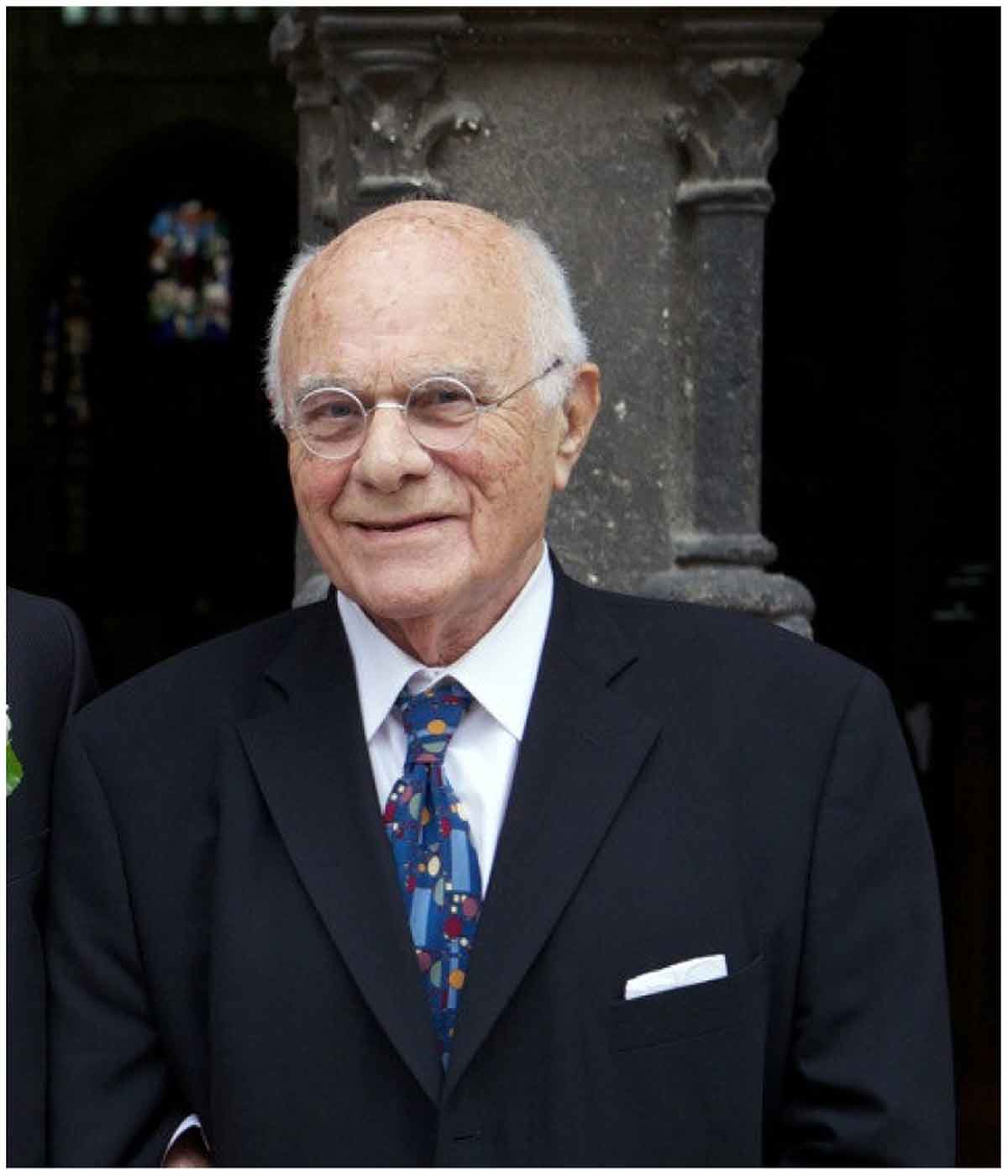

Alain Reinberg passed away 26 November 2017 at 96 years of age. He remained highly engaged in biological rhythm research, creative writing, and travel until his death.

Alain Reinberg passed away 26 November 2017 at 96 years of age. He remained highly engaged in biological rhythm research, creative writing, and travel until his death.

Alain obtained his early childhood education in a municipal school in Paris. He joined the boy scouts when 13 years of age and participated in camping activities in the Alps and l’ile d’Oléron and outings to England and Washington D.C. (U.S.A.). The German invasion of France in 1940 caused the Reinberg family to relocate from Paris to the “free zone” of Lyon where Alain earned his Baccalauréat from the University of Lyon while working for H. Cardot, Professor of Physiology at the university’s affiliated marine biology station in Tamaris. However, due to concern about the disruption of his scientific activities in Tamaris, Alain returned to Lyon to attend the School of Fruit Growing and Viticulture of Ecully. Perhaps, this is where he gained appreciation for the effects of 24 h, lunar and seasonal ambient light signals on botanical species that later impacted his biological rhythm research career.

The aggressive anti-Semitic regulations and Jewish persecutions worsened by the time of his graduation. Jewish students and faculty were banned from French educational institutions. In 1942 Alain joined the armed resistance organization, Francs-Tireurs et Partisans (renamed in 1944 as the French Free Forces), formed by members of the French Communist Party. He adopted the pseudonyms of Rimbert and Rivoire while operating underground in Haute Savoie and making numerous clandestine passages across the Franco-Swiss border between April and June 1943. While at the Institute of Physiology – and with the complicity of Professor Emile Terroine, Chair of General Physiology of the Faculty of Sciences-Strasbourg and an active Resistant also – Alain printed leaflets, illegal newspapers and false identity papers. He rose to the rank of medical sub-lieutenant in the bataillon sanitaire commanded by Gay-Toulon and identified with service certificate A 108525; it listed Alain participated in propaganda operations and liberation of Haute-Savoie, Annecy and Maurienne (battles of Aiguebelette, Epierre and La Chambre). Obviously, Alain was a prime target of the gestapo of Lyon, and in 1943 he received written notification to report to the Service du Travail Obligatoire (Compulsory Labor Office). He hid from the authorities and with the assistance of Aimée Stitelmann – a brave 20 year old Swiss lady – escaped to Switzerland where he eventually gained refugee status. Nonetheless, he was incarcerated in the Saint Antoine and Camp de Champel prisons until release in autumn 1943 “on the condition of having a university activity”. This allowed Alain to resume his academic studies in Switzerland. However, he was not welcomed warmly by the Faculty of Sciences. He was relegated to an isolated laboratory where he lived and researched in uncomfortable conditions – room temperature between 3 and 5 °C – the biology and survival of isolated invertebrate hearts while also continuing clandestine activities against the occupation.

Alain returned to France in June 1944 “because inaction weighed me down”. With the assistance of Professor Emile Terroine, Alain was able to continue the study of medicine and prepare his Ph.D. thesis. During these difficult financial times, he earned needed income writing poems under the name of Alain Rimbert that were published in Porrentruy, Switzerland in 1945 in a collection entitled French Poems Written in Switzerland at the Time of Exile and also short stories – Frontière – published in Suisse Contemporaine and Jean et la Ville. He additionally composed articles under the pseudonym Pierre Bertin – anagram of Rimbert – on Péguy and Nietsche that were printed in Traits, the journal of intellectual resistance published in Lausanne (Switzerland). After the liberation of France, Alain worked as a correspondent journalist for the Annecy Progress Lyon. One of his assignments was the trial of Constable Lelong, a German collaborator who exposed the location – Glières plateau – where Resistants met to organize clandestine activities against the occupiers.

Alain married Marie-Anne Spanjaard in Lyon in 1945. She had moved with her Jewish parents to Lyon (Rhône) from Paris following the German defeat of France in June 1940. Marie-Anne attended the University of Lyon’s School of Dentistry. Germany took control of southern France in November 1942, and by order of the notorious gestapo chief Klaus Barbie persecution of Jews intensified. Following seizure by the Germans of several Spanjaard family friends in April 1943, a classmate and close friend, Andrée Gay, protected Marie-Anne by procuring an authentic identity card in her name. Both graduated from dental school in 1945. Marie-Anne became an accomplished dental surgeon in Paris, and the two of them remained close friends until Marie-Anne’s death in 2001. Alain succeeded in having Andrée Gay designated as the “Just among the Nations” by the Yad Vachem Holocaust Memorial Museum in Jerusalem (Israel) for the kindness, sacrifices, and life-saving acts she bravely extended to protect Marie-Anne, Alain and their parents from the nazis. Alain, himself, was recognized by the French government for his heroic bravery in resisting the German occupation; he received the meritorious awards of the Volunteer Combatant Resistance Medal in 1946 and French Medal of the Resistance in 1954.

Alain obtained his Doctorate of Science Degree (Ph.D.) in 1952 and Doctorate in Medicine Degree (M.D.) in 1954, earning the prestigious Laureate of Faculty designation. He specialized in endocrinology and metabolic diseases. He became a CNRS (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) Research Fellow in Physiology in 1954, then a Research Master, and Research Director of the Pharmacology Section of the CNRS in 1983. Early in his medical career Alain became intrigued with researching circadian and other period rhythms and their importance to medicine, publishing the results of his first investigation in 1954. The idea biological variables display predicable-in-time rhythmic variation was then a new and disruptive concept. Because Alain’s research seemed to challenge the prevailing concept of relative constancy of the milieu intérieur proposed by the French scholar Claude Bernard in the middle of the nineteenth century (later termed homeostasis by Walter Cannon), most medical scientists were skeptical. In actuality, the whole of Claude Bernard’s research findings went underappreciated in that he described temporal variation in hepatic glycogen content according to the clock hour of liver dissection. Alain had faith in his research pursuits, and was confident the findings by him and others would prove the naysayers wrong, and he succeeded! Alain formed the “Research unit on Human Chronobiology” at the CNRS in 1971, and it was renewed after every scheduled assessment until his retirement in 1990. In the context of the 1950s and 1960s, he fought and won a difficult battle against the scientific community infatuated with and blinded by homeostasis as the guiding principle of vertebrate biology and medicine. A strong personality like Alain Reinberg was required to lead the development of chronobiology as a legitimate biological and medical science. Alain continued his very active career in chronobiology through research and teaching after age-mandated “retirement” by French law. In fact, PubMed lists him as author of 85 journal articles between 1991 and 2017.

Alain’s accomplishments in chronobiology are numerous. He enlisted the cooperation of the speleologist Michel Siffre to conduct the first out-of-time (time-cue isolation) cave experiments in the 1950s. They demonstrated persistence of human circadian rhythms in environmental conditions devoid of external time cues, thereby supporting the hypothesis of their endogenous origin and synchronization in phasing and period to 24.0 h by exogenous time cues. At that time, many hypothesized rhythms were derived either as a conditioning effect by or response to environmental 24 h cycles. A partial list of Alain’s research endeavors and achievements include investigation of: endocrine rhythms; biological time structure in health and disease; chronopharmacology, chronotoxicology and chronotherapy of medications; chronopathology of acute and chronic medical conditions; chrononutrition; shift-work chronobiology; chronoepidemiology of accidents and injuries; human out-of-time experiments; chronobiology of jetlag (circadian rhythm desynchronization); genetic mechanisms of human circadian time-keeping; 24 h, lunar, 7 d and annual plant, sea and land animal – including human – rhythms; and light-at-night and other inducers of circadian disruption.

Alain attended and organized many chronobiology meetings and closely interacted with leading “early generation” chronobiologists, such as Franz Halberg, Erhard Haus, Larry Scheving, Leland Edmunds, Nathaniel Kleitman, Jürgen Aschoff, Joseph Rutenfranz, Theodor Hellbrügg, Gunther Hildebrandt, John Mills, Peter Colquhoun, Colin Pittendrigh, Israel Ashkenazi and Wop Rietveld. By the 1970s, laboratory animal investigations began to reveal circadian rhythm-dependent differences in the pharmacokinetics and/or beneficial or adverse effects of medications. At that time the chronopharmacology of medications in humans was little studied, and Alain was among the first to conduct such research. His early work involved optimization of therapeutic outcomes and minimization of adverse effects of synthetic oral corticosteroid therapy. He confirmed the findings of early pioneers that timing corticotherapy in small to moderate doses once-a-day in the morning – at the commencement of the diurnal activity span – avoids the adverse effects that resulted from the most favored equal-interval, equal-dose treatment strategy. Moreover, he demonstrated 80% of patients who routinely ingested their oral corticotherapy once-daily at the beginning of the daytime activity span, even for as long as 20 years, maintained normal cortisol level, while those who routinely ingested it according to the popular equal-interval (homeostatic-based) strategy evidenced significant suppression of cortisol production plus abnormality of the circadian cortisol rhythm, thereby challenging the dogma advocated by classically trained pharmacologists and medical doctors of the conventional three or four times-a-day treatment paradigm based on the concept of homeostasis.

Some of Alain’s early investigations entailed circadian and menstrual rhythms of skin reactivity – a primary means of making the definitive diagnosis of specific allergen sensitivities and assessing the pharmacodynamics of antihistaminic medications. He substantiated significant morning vs. evening ingestion-time differences in the duration and extent of the therapeutic effect of several popular antihistamine medications that were independent of their pharmacokinetics, which also varied significantly according to the circadian time of administration. These findings led Alain to propose the concepts of chronokinetics – biological rhythm-dependencies of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination – and chronoeffectiveness – biological rhythm-dependencies in drug effects. The finding that drug chronokinetics did not predict drug chronoeffectiveness lead Alain to propose additional new concepts, such as the chronesthesy of biosystems, defined as biological rhythm-dependent differences in target cell, tissues and organ susceptibility to actions of medications, and chronergy, defined as biological rhythm-dependent differences in the overall effects of medications according to their chronokinetics and chronesthesy.

Alain was indisputably the leader of clinical chronobiology and chronotherapeutics. His accomplishments were internationally recognized through his more than 600 journal articles, book chapters, books and monographs. He was elected General Secretary (1963–1974) and then Vice President (1975) of the French Society of Endocrinology and honored for his scientific contributions by the French Academy of Sciences in 1977 and various academic societies of the United States and Germany in the 2000s. He established the International Journal of Chronobiology in 1973 and served as its editor-in-chief until the end of 1983. In 1984 he co-founded with Michael Smolensky (The University of Texas-Houston Health Science Center) the academic journal Chronobiology International (now celebrating its 35th year of publication), and served as its co-editor-in-chief for more than 20 years. He organized numerous chronobiology meetings of the French Society of Chronobiology and International Society of Chronobiology. In 1978 Alain organized the seminal satellite Symposium of Chronopharmacology as part of the 7th International Congress of Pharmacology to introduce to conventionally trained pharmacologists and pharmaceutical company scientists the rapidly developing field of biological rhythms and medications. The meeting was a huge success, and the proceedings were published as a volume entitled Chronopharmacology (Pergamon Press) in 1980. Thereafter, Alain established in collaboration with Michael Smolensky and Gaston Labrecque (École de Pharmacie, Université Laval) the Association des Rhythmes Biologiques et Médicaments (Association of Biological Rhythms and Medications) to facilitate organization of international conferences on chronopharmacology and chronotherapeutics. The 1984 and 1986 conferences took place in Montreux (Switzerland); the 1988 and 1990 ones in Nice (France); the 1992 and 1994 ones in Amelia Island (Florida, U.S.A.) and the 1999 one in Williamsburg (Virginia, U.S.A.). Commencing in 1984, the same three colleagues established and edited the Annual Review of Chronopharmacology and Chronotherapeutics (Pergamon Press).

Alain mentored many young and seasoned scientists. He created with Florian Delbarre (University René Descartes in Paris) the first course and university diploma of chronobiology. He was also a regular participant in Bjorn Lemmer’s annual international course of chronobiology offered at the University of Heidelberg, and he was an active visiting professor at academic institutions in Europe – Frankfurt and Heidelberg in Germany; Rome, Florence and Bari in Italy; Tel Aviv (Israel), Antalya (Turkey) and Monastir (Tunisia) in the Middle East; and Berkeley, Davis, Houston and Minnesota in the U.S.A. Alain authored several books on biological rhythms for the public, scientists and clinicians: Biological Rhythms; Des Rythmes Biologiques à La Chronobiologie; Les Rythmes Biologiques; Nos Horloges Biologiques Sont-Elles à L’Heure?; Le Temps Humain et Les Rythmes Biologiques; L’Art et Les Secrets du Temps: Une Approche Biologique; Chronobiologie Médicale, Chronothérapeutique; Chronobiologie et Chronothérapeutique; Biological Rhythms and Medicine: Cellular, Metabolic, Physiopathologic and Pharmacologic Aspects; and Clinical Chronopharmacology.

Alain was fond of swimming, sailing, skiing, and other sports. He was a creative and clever man and loved the arts and artists. As a young doctor, he frequently befriended struggling young talented artists, and his kindness was occasionally rewarded with a gifted painting; one which hung in his living room depicted Marie-Anne’s and Alain’s children when youngsters. He loved to visit museums of all types in Paris and other cities and countries he visited. He was attracted to abstract art and was able to clearly discern images and messages from what seemed to be chaos. In the same manner, he was able to detect and understand complicated and obscured temporal patterns of human biological functions and incidents. Alain enjoyed music of various kinds – classical, modern and jazz. He was an excellent writer and had an overflowing imagination that extended beyond science. He sought funny or incongruous themes to juggle and wield contrary perspectives and neologisms as wonderful charades to delight readers of his works. Alain’s sense of humor extended to his scientific endeavors and career. One of us (YT) was asked to comment on Alain’s discoveries at the 2005 meeting of the French Society of Chronobiology held in Strasbourg. Alain later published a response in the journal of the French Society, Rythmes, stating:

I still do not know what a discovery is because the strongest one, apparently, can have questionable aspects. However, we must accept the notion of discovery, because without it there would be no career researcher. It seems to me that since the 20th century, it is difficult to attribute one-to-one a researcher with a discovery. Good ideas are like ripe fruit; their picking is typically not a game of solitaire that is played alone. The discoverer is rarely a single individual, and typically academics do not carefully read the scientific literature; discovers often do not acknowledge competitors. Sooner or later one will discover that the discoverer is not the only one to deserve this title. What is a discoverer? He is probably a magician who produces a live rabbit from a hat slapped inevitably until empty. In this kind of magic, there’s always a trick

Alain authored four novels in addition to the scientific books and poems he penned during the war years – The Top of the Shell (1967), The Foolish Beast (1972), Should We Forget These Things? (2011), and A Whale with a Hat Melon (2017). He also published a collection of short stories – Unimportant Beings (2013) – and a remarkable essay in which he juggles the creative art of painters, musicians and literary authors into representative expressions of biological rhythms – L’Art et Les Secrets du Temps (The Art and Secrets of Time). Film-making was another one of Alain’s talents. He acquired a professional Paillard-Bolex B8 multifocal lens camera in the early 1950s and created three short 8 mm silent family films – The Flying Saucers (1955), The Journey to Greater Suburbia (1955), and western entitled A Bear (1956). They featured his children, nephews and nieces as actors in surrealist and picturesque French settings.

Alain’s state of health, which he referred to as “many small problems related to the wear and tear of aging”, did not limit his activities. With his two hip prostheses, he forded the Jordan River in Israel, flew in a hot air balloon in Cappadocia (Turkey) and endured the hot temperatures and long walking distances when touring southern India. When 90 years of age, he eagerly travelled to the U.S.A. to visit and work with one of us (MS) at The University of Texas in Austin (Texas) and to participate in the History of Chronobiology Conference at the University of Minnesota (Minneapolis, Minnesota). He would not have missed these events and opportunities for anything.

Alain Reinberg and his wife Marie-Anne were kind persons who welcomed with warm hospitality scholars and associates from all countries of the world into their Paris flat that was tastefully adorned with art of famous painters, antiques of all types, book volumes of art, music, culture, etc. Such gatherings were common, especially when chronobiologists were in Paris to participate in the annual course of chronobiology or plan collaborative biological rhythm activities and research projects. They typically featured fantastic meals prepared by Marie-Anne, wonderful French wines hand-picked by Alain and scientific, political and other discussions. Alain was an outstanding person, and his kindness and accomplishments live on in the hearts and minds of his friends, colleagues and students and also through his many contributions to the field of chronobiology.

Michael Smolensky and Yvan Touitou in collaboration with Olivier Reinberg

Sleep Medicine Program, Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine, McGovern School of Medicine, The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Houston, TX, USA

Yvan Touitou

Chronobiology Unit, Fondation A. de Rothschld, Paris, France

Olivier Reinberg

Department of Pediatric Surgery, University Hospital of Lausanne (CHUV), Lausanne, Switzerland

[email protected], [email protected]