ABSTRACT

The global climate crisis continues to endanger the well-being of natural environments and the people who depend on them. Building elements of environmental identity may better connect youth to the changes underway. However, little work has investigated how experiencing a climate change-impacted landscape may support environmental identity shifts. This study explores such shifts in the context of a wilderness science program for youth in a glacier-dominated landscape with visible signatures of long-term change. We use a qualitative approach to investigate environmental identity development, relying on Clayton’s (2003) environmental identity model as a theoretical construct. We find that two aspects of environmental identity shifted the most: (1) relatedness to the natural environment and (2) pro-environmental motivation. Emergent themes from the analysis reveal that these changes arise from better understanding how ecosystems are interconnected, understanding human impacts on the environment, and witnessing first-hand the scale and rate of glacier loss. Our results imply that educators can privilege these aspects to support environmental identity shifts. Ultimately, our findings highlight that personally witnessing a visibly climate-impacted landscape may be powerful in promoting better environmental stewardship in response to the climate crisis.

1. Introduction

As the global climate continues to warm, consequences for landscapes, ecosystems and people continue to expand and intensify (Masson-Delmotte et al., Citation2018). From increasing heat waves to melting sea ice and glaciers, impacts from ongoing climate warming are numerous, threatening and increasing (Masson-Delmotte et al., Citation2018). While many youth across the globe today play active and leading roles in the movement to combat climate change (Fisher, Citation2016), others remain sceptical and dismissive of the seriousness of the issue (Ojala, Citation2015). Moreover, while some school environmental science curricula have played an important role in overcoming scepticism through climate literacy (Stevenson et al., Citation2014), in other instances school science may not directly or completely address climate change (Meehan et al., Citation2018; Vujovic, Citation2014). In order to continue growing youth engagement in climate change issues, outdoor environmental education programs (hereafter ‘outdoor education’ for brevity) may be primed to help fill the gap.

Outdoor education offers opportunities to learn in, about and for the outdoors (Ford, Citation1986; Gilbertson et al., Citation2006; Wattchow & Brown, Citation2011), combining the tenets of experiential and environmental education (Adkins & Simmons, Citation2002). Experiential education draws together direct experience and in-context action, infused with critical reflection aimed at increasing knowledge and skills and clarifying values (Ford, Citation1986; Kolb, Citation2014). In such a context as geoscience field trips, for example, benefits can include forging an affective response that improves learning outcomes and initiating students into a scientific community of practice (Mogk & Goodwin, Citation2012; Streule & Craig, Citation2016). Environmental education, second, focuses on exhibiting how natural environments function and how a healthy, diverse ecosystem can be preserved for future generations (Palmer, Citation2002; Stapp, Citation1969; Tanner, Citation1980). Moreover, it carries as a principal goal the fostering of an engaged citizenry motivated to act on behalf of the environment (Chawla & Cushing, Citation2007; Hungerford & Yolk, Citation1990; Tilbury, Citation1995; Wals et al., Citation2014). Taken together, these tenets yield a powerful platform for providing participants in outdoor education programming an opportunity to be not only immersed in nature, but also moved towards action by it.

One way in which outdoor education can be shaped to help encourage pro-environmental behaviour is through promoting identity shifts among people who experience nature (McGuire, Citation2015). Environmental identity is the aspect of identity that encompasses one's relationship to nature and involves the ways in which people position themselves and are positioned with respect to the non-human natural world. It is both a product based on personal history, connection and/or social influences, as well as a force that compels certain types of behaviour toward the environment (Clayton, Citation2003). Because of this motivational potential, providing opportunities for people to directly experience a climate change-impacted landscape may help to shift stances towards the natural world through a personal encounter with an environment in flux. However, while some studies to date have established links between outdoor education and environmental identity development (McGuire, Citation2015; Williams & Chawla, Citation2016), few have done so in the context of climate change.

Outdoor education opportunities in glacier landscapes offer an ideal opportunity to bear witness to change, as many show dramatic visual evidence of their retreat. In much of the world, including Alaska and Washington in the United States, glaciers began to retreat concurrently with the late nineteenth-century onset of the Industrial Revolution (Crutzen & Stoermer, Citation2016). Shrinking mountain glaciers are directly linked to climate change, with changes in size that correlate strongly with global air temperatures (Dyurgerov & Meier, Citation2000). Today, the centennial-scale retreat of glaciers represents the cumulative effects of climate change (Roe et al., Citation2017), thereby serving as visual evidence of climate change in places where that difference in size can be seen on the landscape. For these reasons, glaciers have in recent decades become a prominent symbol of climate change in popular media (Carey, Citation2007; Doyle, Citation2009) and citizen discourse (Aram, Citation2011; Leiserowitz, Citation2005), largely attributable to glaciers’ dual connection to climate change both as archives of past climate that can be retrieved in ice cores and as victims of rapid disintegration in current-day warming (Carey, Citation2007).

To date, few studies have explored the potential for interactions with climate change-impacted landscapes to support pro-environmental outcomes. One study by Stapleton (Citation2015) investigated outcomes of an overseas travel program for youth to climate change-impacted communities in South Asia, but focused primarily on the role of social interactions in participants’ environmental identity development. Another study by Schweizer et al. (Citation2013) examined outcomes of place-based communication in U.S. national parks, but through a framework related to civic engagement in climate change rather than environmental identity. Moreover, both studies focused on landscapes in which climate change impacts are more subtle and difficult to view directly. As described above, glaciers are one of few landscape features that can offer dramatic, visual evidence of cumulative change. We therefore posit that interacting with such landscapes may be especially powerful in promoting environmental identity shifts. This study examines how a residential youth mountaineering and science expedition, Girls on Ice, may develop participants’ environmental identity through a week of living on, exploring and scientifically studying the rapidly and visibly changing landscapes surrounding two U.S. Pacific Northwest glaciers.

2. Theoretical perspective

2.1. Environmental identity

Environmental identity encompasses reflection on the natural, non-human environment and, in particular, on one's position within it. We situate our study in Clayton’s (Citation2003) conceptual and operational definition for environmental identity, which is rooted in work by Rosenberg (Citation1981) that discusses the ways in which aspects of self-concept/identity are both a product and a force. Clayton proposes that, along with other aspects of an individual's identity, environmental identity is: ‘one part of the way in which people form their self-concept: a sense of connection to some part of the non-human natural environment … that affects the ways in which we perceive and act toward the world’ (Clayton, Citation2003, p. 46).

Environmental identity is both socially and individually constructed. These aspects respectively come to the fore depending on context, i.e. whether one is focusing on the self as unique or as a member of a group (Clayton, Citation2003). As a result, one's environmental identity may arise not only based on a personal sense of connection to the natural world, but also to others with similar views. Indeed, identification with a group of people who possess similar worldviews and/or political affiliations has been found in certain contexts to significantly influence one's environmental attitudes and behaviours, prompting group members to act in more or less pro-environmental ways (Fielding & Hornsey, Citation2016). Individual and social aspects of environmental identity can, as with other forms of identity, either be in harmony or in tension with one another. Ultimately, whether social aspects of environmental identity will dictate how one thinks and behaves towards the environment will depend on whether social dynamics are more pertinent within a particular context.

In Clayton's formulation, in addition to social influences, many other more individualistic factors intersect to dictate how one feels about the non-human natural environment, where/how one feels they fit into it, and how one behaves towards it. Clayton proposes that at the individual level, environmental identity is influenced by such elements as: personal history, emotional attachment, autonomy, relatedness, competence and pro-environmental motivation. We briefly summarise Clayton's description of each element here.

Personal history refers to one's prior experiences in nature which, whether positive or negative, impact the way in which one thinks about and behaves towards the natural environment (Clayton, Citation2003). Related to this, emotional attachment is based on experiences that are emotionally significant and that stem from a tendency for humans to be drawn to natural landscapes. Autonomy then describes how in those natural landscapes one may feel a sense of freedom from the expected behaviours and constraints of other social settings, a scenario which can offer a chance to build self-actualisation by feeling at ease to be oneself.

Relatedness to the natural environment occurs when one has the ‘opportunity to feel like a part of a functioning system’ (Clayton, Citation2003, p. 50). While for some, this may be experienced in a spiritual sense, for others it may arise from feeling part of a larger ecosystem, environment or world. Naess (Citation1973) was the first to coin the term ‘deep ecology’ to refer to a movement that rejects anthropocentrism and profit-driven motivations (‘shallow ecology’) in favour of maintaining biological diversity, egalitarianism with other forms of life, and relational links between ecosystem components, all driven by ecological equilibrium first and foremost. This concept encourages thinking of one's self as a part of, and not separate from, the natural world.

Competence in a natural setting is rooted in a sense of self-sufficiency, an ability to travel around independently, and the capacity to survive and thrive in the outdoors while facing any fears (Clayton, Citation2003). Clayton describes how increased competence leads to environmental identity development because the natural environment serves well as a setting against which to test oneself and to learn one's limits and abilities. Hinds (Citation2011) observed, for example, that a residential woodland adventure program for marginalised adolescents resulted in improved self-identified perceptions of skills-based competence. The human inclination for competence is also cited as a common driver in pro-environmental motivation (De Young, Citation2000).

Pro-environmental motivation is the element of environmental identity that acts as a force, by enabling one to see how they are personally relevant in environmental issues, thereby affecting their thinking and behaviour (Clayton, Citation2003). Many studies have identified different experiences that can encourage this type of mindset. Such benefits as time outdoors in pristine environments (Cachelin et al., Citation2009), personal growth and transformation (D’Amato & Krasny, Citation2011), and even strong autobiographical memories many years after the experience (Liddicoat & Krasny, Citation2014) were all identified as not only the most significant outcomes of different outdoor education programs but also as the most strongly linked to pro-environmental behaviour. Another significant body of research has connected pro-environmental behaviour to having significant life experiences outdoors (Chawla, Citation1998). Tanner (Citation1980) was the first to document that for many who chose a career in conservation, memorable youthful experiences in nature, and particularly in environments relatively untouched by humans, were cited as the most significant experiences in developing their pro-environmental interests. Decades later, another study that conducted interviews with youth environmental leaders again confirmed that formative life experiences in the outdoors were still described as key to the subjects’ interests in pro-environmental activism (Arnold et al., Citation2009).

In this study, we draw from Clayton's (Citation2003) theory on environmental identity development to help us answer: in what ways does interacting with a climate change-impacted glacier landscape influence aspects of participants’ environmental identity?

3. Context of the study

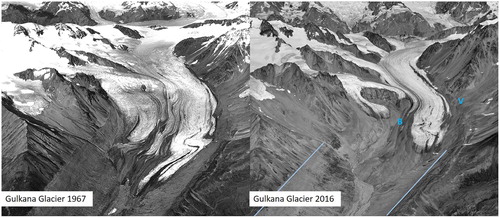

This study was undertaken in the context of the Girls on Ice program, a science, art and mountaineering experience for youth aged 16–18 who identified as female at the time of the program. Each year, 2 teams of 9 participants and 3–4 instructors spend 12 days together, including 8 days on a mountaineering expedition in a wilderness setting dominated by glaciers. Girls on Ice was developed by author Pettit in Washington State in 1999 and has since been adapted for a number of other locations, including Alaska, which author Young co-developed. The Washington program takes place on the Easton Glacier on Mount Baker (indigenous names: Kweq’ Smánit, Kwelshán, Kwelxá:lxw, and Kwelshán), and the Alaska program is located on the Gulkana Glacier (C'ulc'ena’ Luu’) (Kari & Smith, Citation2017) in the Eastern Alaska Range. During the field portion of the program, participants live on, explore, and study a glacier and its surrounding landscape (). They engage in inquiry-based, instructor-led and participant-designed scientific field studies, learn mountaineering skills and participate in art activities. The program emphasises the interconnected nature of different disciplines (e.g. art, mountaineering, and physical, chemical and biological sciences).

Figure 1. Aerial view of the Gulkana Glacier (C'ulc'ena’ Luu’), site of the Girls on Ice Alaska program. Left and right photos respectively indicate the extent of the glacier in 1967 and 2016, showing continued dramatic retreat and thinning over the past 50+ years. Features of interest are highlighted in the right panel, including: the main campsite for the 8-day backcountry portion of the trip (marked as ‘B’ – for a close-up view, see ); one of our hiking objectives (V), a viewpoint atop the late 1800s (i.e. Little Ice Age) lateral moraine, approximately 250 m above the current-day ice surface; (c) the late 1800s areal extent of the glacier (light blue lines), delineating the bare, more recently exposed light grey slopes beneath the more weathered rock above. Modified from repeat photos courtesy of the United States Geological Survey (https://www.usgs.gov/news/fifty-years-glacier-changeresearch-alaska). Landscape features on and around the Easton Glacier on Mount Baker (Kweq’ Smánit, Kwelshán, Kwelxá:lxw, or Kwelshán) are very similar.

The Girls on Ice program aims to provide the opportunity to participants of diverse cultural, ethnic/racial, socio-economic and geographic backgrounds from across the United States (with occasional international participants). In order to remove barriers to access, the expedition is provided at no cost to the participant, although a small, individualised fundraising goal is encouraged to instil a sense of commitment.

During the year of this study, the program invited applications from female-identifying youth. Several studies have examined the benefits of outdoor education programming for all-female-identifying participants, such as promoting feelings of safety, increased connection to others and freedom from stereotypes (Whittington et al., Citation2011), as well as long-term resiliency (Whittington et al., Citation2016). Moreover, such programs have been found to help in overcoming barriers to female participation in the outdoors such as access, peer and family expectations, and physical and environmental factors (Culp, Citation1998). During the year of this study, the Girls on Ice program participated in this educational model through an all-female-identifying team of instructors, coordinators and volunteers, as well as participants. Nonetheless, this study is not rooted within a feminist theoretical framework, in the sense that it does not focus on the female lived experience and the nature of gender inequality. While recognising that gender and environmental identities may intersect, we did not explicitly invoke an intersectionality approach. Rather, this study's focus is environmental identity as it relates to participants’ experience of and reaction to a wilderness environment in flux. We do, however, address implications of this framework in Section 6.

Another thorough description of Girls on Ice can be found in Carsten Conner et al. (Citation2018), a study that focused on the impacts of the program on the participants’ notions about the practices of field science. Here, we outline the program elements of greatest relevance to environmental identity.

3.1. Camping on, living near and exploring a glacier

During the 8 days in the field, participants in Girls on Ice are completely immersed in a glacier-dominated alpine landscape (). Participants camp in tents pitched directly beside the glacier, in Washington, or on top of it on a band of rocks, in Alaska (). Daily excursions allow for the exploration of different glacier zones, such as crevasse fields, zones with meltwater features, recently deglaciated areas, and moraines (rubble piles marking the former glacier extent on the hillside). During each program, participants also stand beneath and climb 100s of metres to the top of the lateral moraine, a feature analogous to a ‘high water mark’ left behind as each glacier has thinned in the past ∼150 years (). Similarly, the terminal moraine, a hill of rubble marking the glacier tongue's former position, provides a visual sense of scale to the ∼2.5–3 km of retreat experienced by each glacier.

Figure 2. Participants gather for a meal at the kitchen area at base camp on the Gulkana Glacier (C'ulc'ena'Luu’) in Alaska, in front of the active Gabriel Icefall. Participants’ sleeping tents are also in the vicinity, located atop the same exposed band of glacier-eroded cobbles. Photo by lead author.

3.2. Modelling pro-environmental behaviour

The Girls on Ice program teaches and models a ‘leave-no-trace’ ethic, a standard in the outdoors field that espouses minimising one's environmental footprint when travelling through and camping in nature. Instructors teach leave-no-trace principles on the first day of the program and revisit them routinely throughout the days in the field, both through explicit discussion and modelled behaviour. Principles of leave-no-trace include camping on durable surfaces devoid of delicate plant life, and picking up and packing out even the smallest spilled food scraps or other ‘micro-trash.’

3.3. Learning ecosystem interconnectedness

Girls on Ice focusses conceptually on the interconnectedness of landscapes, ecosystems and humans. This focus echoes the recent international emphasis on teaching systems thinking in the classroom (Gilissen et al., Citation2020). Teaching from a systems perspective emphasises relationships between different system components, including interdependencies, energy flows, feedback loops and other elements of connected systems (NGSS Lead States, Citation2013). In Girls on Ice, participants learn about socio-ecological systems by means of a combination of hands-on, instructor-led activities, reflection discussions and participant-led science experiments. For example, instructors guide the participants to mentally trace the path of glacial meltwater from source to sea, along the way discussing its influences on ecosystem components as broad as salmon fisheries and ocean acidity. Instructors also link these lessons back to humans, by discussing both human impact on ecosystems through resource use and climate modification and, simultaneously, the dependence of humans on the health of those same oceans, fisheries and wildlife populations. Many of the instructors are graduate students and research professionals in the natural sciences, and thus have deep disciplinary knowledge of the landscape and ecosystems.

4. Methodology

This study is a bounded case study (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation2007) that investigates the experience of 15 girls learning and camping in a glacier environment during the Girls on Ice program. We use qualitative methodology, an approach aimed at ‘understanding how people interpret their experiences, how they construct their worlds, and what meaning they attribute to their experiences’ (Merriam & Tisdell, Citation2015). A qualitative approach to data collection and analysis is well-suited to our study, as we aim to better understand how participants interpret their experience of the glacier landscape, how that may influence how they construct their post-program worlds in terms of pro-environmental behaviour, and what meaning they attribute to their time on a glacier during the Girls on Ice program. Moreover, our interest was in understanding the ways in which any changes in elements of participants’ environmental identity occurred in the context of Girls on Ice, a task better suited to descriptive qualitative data than to quantitative metrics.

We used a participant-observer approach, in which the lead author worked alongside and observed the participants. This gave her an ‘insider's view’ and helped reduce any potential reactivity on the part of participants. The other authors were involved with data analysis, program design, and/or writing.

Data collected from the 15 enrolled study participants included semi-structured interview and qualitative (i.e. open-ended textbox) survey data. Questions were designed to learn about participants’ ideas and feelings about the environment after engaging with nature in general and the glacier in particular. Responses were transcribed and coded using a directed qualitative coding approach with codes developed first from theory and then refined. Findings were grouped according to emergent themes. Further details are given below.

4.1. Participants

The program participants were recruited and selected through an online application process that asks short essay questions about each applicant's life interests, day-to-day life and motivation for applying. The team was purposefully selected to include participants from a variety of socio-economic backgrounds, geographic origins, ethnic/racial backgrounds, family situations, personalities, interests, academic backgrounds, and experience levels in outdoor and science. Specifically, participants’ self-reported racial and ethnic backgrounds were 27% Indigenous (including Alaska Native and Canada First Nations), 20% Latina/Hispanic, 20% Caucasian/white, 13% Black (including African American and African), 13% Multiracial and 7% South Asian American. Academic backgrounds ranged from small, public K-12 schools in rural locations to medium-sized private and large, public, urban high schools. Participants reported having many scientific and non-scientific interests, ranging from wildlife biology to public health and from fine arts to journalism.

We offered enrolment in this study to the 18 applicants selected for 1 year of programming in the mid-2010s (nine for each of two Girls on Ice expeditions). Of these, one declined to participate and two did not attend the program due to unforeseen circumstances. Thus 15 girls were enrolled in the study (7 from the Alaska program and 8 from the Washington program). Participants ranged from 16 to 18 years old.

4.2. Interviews

One-on-one interviews were conducted during the last 2 days of each 12-day program (i.e. after the field expedition). These interviews were conducted either in person (Alaska program) or remotely over video-conference (Washington program). The interviewer was a learning scientist external to this study but familiar with the Girls on Ice program, who was not previously acquainted with the participants. The interview protocol included seven multi-part questions designed to target the participants’ ideas, stances and feelings about environment, ecosystems and climate change as a result of exploring and engaging with the wilderness and, specifically, the glacier. Some questions were formatted as retrospective, asking each individual to think back to the beginning of the program and to compare and contrast to their thoughts at the end. The interviews were semi-structured, allowing for the interviewer to follow up on particular statements by the interviewees, ask for or provide clarification, or reorder questions when appropriate (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2011). Some examples of multi-part questions include: ‘What was the most memorable or exciting part of Girls on Ice? What did you learn?’, ‘Describe how you feel about the environment and ecosystem. Has Girls on Ice changed how you feel about the environment and ecosystem, and if so, how? How did you feel about the environment before participating in Girls on Ice?’ and ‘What was it like to be on a glacier? Did living on, exploring, and learning about a glacier impact how you feel about the environment and/or climate change? If so, how?’ All interviews were audio-recorded by a single interviewer and then transcribed. Interviews ranged between 10 and 20 min in length.

4.3. Qualitative survey responses

Survey data was also collected from participants during the week after the program (n = 15), and approximately 1 year after the program (n = 11), using the online platform SurveyMonkey. In these surveys, participants were asked eight open-ended (no character limit) text box questions. Some questions were designed to learn generally about participants’ experience on the program (e.g. ‘What did you learn about yourself on Girls on Ice?’), while others were more targeted towards understanding participants’ experiences of the glacier (e.g. ‘Did exploring a glacier landscape change how you understand the environment and/or climate change? Why or why not?’). Some questions were again phrased as retrospective.

4.4 Data analysis

To discover patterns within the interview data, we employed a directed qualitative content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005), whereby codes were initially developed from theory, then refined as described below. Two authors (Young and Carsten Conner) first developed a coding scheme using select elements of the environmental identity framework of the Clayton (Citation2003) environmental identity framework listed in Section 2.1 that were relevant to independent memos taken during a preliminary reading of four sample transcripts, namely emotional attachment, relatedness, competence, and pro-environmental motivation. After an initial round of coding on those same four transcripts followed by extensive discussion, the coding scheme was further refined by collapsing select overlapping codes, eliminating others due to a relative scarcity of excerpts, and adding additional codes that were not present in Clayton's framework but that were relevant to our research question and present throughout the data. We also included several child codes grouped under parent code headings. Code descriptions and examples are provided in . At this stage, inter-rater reliability was calculated as pooled Kappa (k = 0.87; De Vries et al. Citation2008). Codes were not modified after inter-rater reliability. Author Young then performed the final round of coding of all interview transcripts using Dedoose software.

Table 1. Final codes applied to interview excerpts, along with descriptionsand examples of each.

Next, author Young also applied these same codes to participants’ written responses to the open-ended survey text box questions gathered immediately and 1 year after the program. These data were complementary to the interview questions. Analysis revealed little difference between time periods (i.e. immediately post-program versus 1 year later) in terms of content and themes, though some responses 1 year after the program show more sophisticated language. This is not unexpected, given that the passage of time allowed participants to reflect on their experience and perhaps develop a more polished narrative. We label all 1-year post-program quotations accordingly in the Findings and Discussion sections below. Nonetheless, given the similarity in content, we analyse these data together with the survey responses collected immediately after the program, as well as the interview responses. Finally, we looked for emergent themes within and across codes, and grouped them as they pertain to different aspects of environmental identity development.

5. Findings and discussion

Four themes emerged from the data with respect to experiencing a glacier landscape. Two of the themes were in line with two key elements of the Clayton (Citation2003) environmental identity model: relatedness and pro-environmental motivation. These themes appear below as Themes 1 and 2: (1) a sense of relatedness to nature builds when ecosystem linkages are brought to light and (2) sharing with others and helping the environment are interrelated concepts.

The other two emergent themes cross-cut those same two elements of relatedness and pro-environmental motivation, suggesting that many participants experience a deepened sense of their position within the natural world in tandem with a call to environmental action. These two themes appear below as Themes 3 and 4: (3) humans can either hurt or help the natural world and (4) witnessing the scale of glacier loss made climate change more real and, in turn, sparked pro-environmental motivation.

We discuss all four themes below.

5.1. Theme 1: Relatedness builds when ecosystem linkages are brought to light

Our data showed that having an increased understanding of ecosystem interconnectedness played a strong role in building participants’ relatedness to the environment. During the program, instructors took a systems thinking approach in their instruction, helping elucidate different processes, patterns and connections in the ecosystem that may have otherwise gone unnoticed (e.g. pointing out how terrestrial plant and wildlife species are distributed relative to the glacier, or explaining how glacial meltwater routes to downstream rivers and the ocean). Participants described how these linkages were made more meaningful by seeing and learning about them in person. For example, one participant reflected,

I guess it's a bigger spectrum, a bigger picture, definitely. Even [an instructor] talking about how the water runs to all the oceans from that one spot, it makes you notice how something so small could still have a big difference. And you read about it in textbooks and whatnot, but it's not the same as actually seeing it and actually understanding that bigger picture.

Participants also reported that having these linkages brought to light made clearer the ways in which they personally fit into the natural world. For example, one participant offered, ‘I felt like I kind of cared for the Earth, but I have a deeper understanding of, what I do, it really affects everything, like the whole ecosystem. It's not just me anymore. Everything is connected’. This increased understanding of the linkages between humans and the environment was a principal science learning outcome of the experience.

Participants further reflected on their own place within these ecosystem linkages. Some described feeling small relative to the bigger picture of the natural world as a result of the experience, while nonetheless sensing their sizeable influence over the environment as humans. Moreover, participants describe the relationship with nature as two-directional, whereby not only can humans influence the environment, but the reverse is also true. One participant for example explained, ‘before Girls on Ice, I didn't have any experience or a connection to the glacier ecosystem. I just thought they were high on the mountains, like, they didn't have any effect on me’. After the program, several participants described feeling overall more in tune with the natural environment, whether with the glacier setting itself or a different landscape. One participant relayed, ‘I feel more connected to all kinds of different landscapes, like, from glaciers to oceans to rivers and deserts’.

5.2. Theme 2: Sharing with others and helping the environment are connected

One of the most frequent sentiments expressed by participants during the post-program

interviews was the desire to share the glacier landscape with other people beyond those in the program. Participants mentioned wanting to share the landscape with family members, the next generation of Girls on Ice participants, or with other people more generally. Several also mentioned wanting to share what they had learned on Girls on Ice in order to teach others. Right after the program, one participant commented, ‘I will do my best to spread the knowledge I’ve gained on the program with as many as I can’.

Paired with this was an interest in helping the environment ‘stay new’ for the next generation of Girls on Ice participants, and similarly in allowing more people to experience the environment ‘as it is’, or as they experienced it themselves. One participant reflected, ‘I would protect it because I want it to make everyone feel how it made me feel, just honoured to see it because it's retreating so fast’. Another participant expressed, ‘It's made me want to do it more because if we don't start taking care of it sooner, then it won't be there for other people to experience and enjoy. Yeah. I want other people to – more Girls on Ice down the road to be able to have the experience that I did. They won't have that if we don't start protecting or changing our ways’.

A desire to protect the environment was a strong part of this theme. All girls reported feeling inspired to undertake new activities to help the environment immediately after the program, and this desire persisted through time. When asked one year later, ‘have you been doing any new activities to help protect/conserve the environment (e.g. recycling, school environmental club, etc.)?’ almost all participants mentioned personal environmental stewardship activities such as recycling, limiting their emissions footprint (e.g. walking/biking/taking transit instead of driving), and reducing water consumption. (While recycling may have been a common response due to its inclusion in the question, it is also frequently associated with pro-environmental behaviour and may even act as a gateway to other behaviours (Berger, Citation1997).) This urge to protect the environment was often connected to wanting to share with others. One year after the program, one participant described, ‘I guess I didn't realise how the environment is connected in so many ways; from ocean to even wildlife. Because of this I feel like I will feel an obligation to do as much as I can to protect the environment so that more people can experience what I got to’.

Some participants also reported that in the year after the program, they had undertaken such activities as working at a wildlife preserve and organising an environmental club at school. This willingness to engage not only in private, personal actions but also in public actions that involve other people differs from a study on younger 13–15 year-old youth identified by their teachers as ‘environmental enthusiasts,’ in which the authors found that navigating the complexities of early teenage years drew the study participants more to small-scale personal actions with no social risk (Eames et al., Citation2018). Our finding that Girls on Ice participants had the confidence to endeavour towards social action helps confirm the hypothesis in Eames et al. (Citation2018) that promoting environmental education in secondary school rather than middle school may be more productive for encouraging larger-scale, more organised pro-environmental action.

Altogether, participants’ desire to share aspects of the program with others manifested as two-directional: participants wanted to educate other people for the sake of preserving the landscape, and wanted to preserve the landscape for the sake of sharing it with other people. This demonstrates that for many participants, pro-environmental motivation is consistent with the notion that an individual's environmental identity and its constituent elements are both a product and a force (Clayton, Citation2003), given that pro-environmental motivation here is the product of participants’ connection with other people, as well as a force that compels their inclusion.

5.3. Theme 3: Humanity can either hurt or help nature

Based on their interactions with the glacier landscape, many participants reported having a deepened understanding of how humans, including themselves, have an impact on the environment. For many participants, having a strengthened sense of relatedness to the natural world due to better understanding human influence was nearly inseparable from a desire to behave pro-environmentally; these aspects of environmental identity were mentioned in tandem. One participant explained a year after the program, ‘Studying Gulkana most definitely [sic] changed my view on climate change. Learning and seeing the impacts of human [sic] living on the glacier, created a want inside me to inform others of the disappearance of our world's magnificent features’. Another summarised more generally, ‘Every place that we encounter has, it [sic] affected by us. So it's important to make sure that our effect is only a positive one and that we continue to protect these places’.

A few participants observed that the relationship between humans and environment is bidirectional. One participant noted simply, ‘The world needs us and we need it’. A year later, another participant also described how humans’ influence on the environment can take two forms: ‘It made me realise that humanity can either hurt or help nature’. Indeed, discussion of humans’ negative influence was frequent; different participants stated: ‘we use a lot of the environment's resources’, ‘I was able to see that humans have a catastrophic impact on the rest of the earth’ and ‘we just are kinda ruining the planet’. Despite these strong negative impressions, participants reported their own desire to have a positive impact on the natural world. One year later, one participant offered, ‘I can't bare [sic] to think that I can hurt it; therefore, I make sure I don't and proactively work towards helping the enviro [sic]’, while another said of the experience, ‘Yes, made me realise climate change is happening and we are the only ones who can take measures to prevent it’.

Participants mentioned several ways in which they realised through practice how their actions impacted the environment. Reflecting on behaviours during the program, one participant remembered,

It was little things we could do. Most people would pick up trash. I would like to think everyone. But we would go further than that. We would pick up every single tiny little crumb that we called micro trash … So that just made you think, like we have this idea that everything is just out of sight, out of mind, you know, and that's not true. And so this program really helped me realize the effects of just everything we do.

Another participant observed,

Like to come from a suburban place where it's so like centered around humans and how humans function and like works to serve humans. And then to go somewhere where it's like no, you have to do these things because that's what's best for the environment I think was refreshing and to some extent challenging.

Our results suggest that the Girls on Ice program design elements of discussing ecosystem interconnectedness and modelling strict leave-no-trace behaviour served to provide a small/local scale example of pro-environmental behaviour that helped solidify the concept of human impact on the environment. Together with an increased sense of personal relatedness to the environment, these concepts act inextricably as strong motivators for behaving in an environmentally responsible way.

5.4. Theme 4: Witnessing the scale of glacier loss made climate change more ‘real’; inspired pro-environmental motivation

The experience of interacting with the glacier proved an especially powerful aspect of the Girls on Ice program for participants. Many characterised the glacier as ‘beautiful’, ‘magical’ and ‘inspiring’, and called interacting with it ‘unforgettable’ and ‘once-in-a-lifetime’. Several participants reported that experiencing the sense of scale was particularly impactful. One participant reflected, ‘it looks big from the camp, but then you get on the glacier and you actually start walking around it, and it's like, oh my gosh, this is so huge. I didn't expect it to be as big as it was until I actually set foot on it. And it was like, wow, this is a big one’. Participants also expressed surprise over the rate of loss of glacier ice over time. One participant stated, ‘And I just thought, I was like, oh my gosh, how could this happen so fast?’ Grasping this rate of change brought up anxiety for several participants, one of whom described, ‘standing where the terminus [the tongue of the glacier] was, like, decades before, and standing where it is now, and even seeing pictures from 1912 to versus now, it's been really scary’.

We propose that the impact of the size and rate of ice loss is consistent with findings from research in museum settings. In exploring the characteristics that make museum artefacts especially powerful for visitors, Leinhardt and Crowley (Citation2002) found that one of the most important features is simply a noteworthy sense of scale (e.g. very large) and/or a size that is different than the observer anticipated (e.g. larger than expected). Although the setting is different, the experience of being dwarfed by an immense and rapidly changing landscape feature – and again, one that has been made legendary by the media (Carey, Citation2007; Doyle, Citation2009; Leiserowitz, Citation2005) – carries the same potential for significant impact.

For many participants, seeing for themselves this surprising rate of glacier change deepened their relatedness to the environment, and particularly to the changes taking place. One participant mentioned, ‘To look at these ideas and concepts in a scientific way, explaining all the change that has occurred within the last few years. I don't know. It just really makes it specific and you really see it and you really worry about climate change in that specific place’. Another participant noted a year after the program, ‘I know that climate change is real, and I have experienced the effects of it at home but seeing the effects of the receding glacier made it real in a different way’. These sentiments suggest that being in an environment that shows clear and visible signs of rapid climate change made the concept more real and relatable.

The understanding that the experience and landscape are under threat of ongoing change led many participants to express feeling ‘worried’, ‘scared’ and ‘sorrowful’. Yet despite this anxiety, most participants nonetheless report being inspired to act pro-environmentally. Participants used a number of terms to describe this motivation, including wanting to ‘protect’, ‘preserve’, ‘save’, ‘keep healthy’, ‘help’, ‘nurture’, ‘love’ and ‘care for’ the natural world. Even more than simply feeling driven to behave pro-environmentally, some reported feeling obligated. Individual participants referred to caring for the environment as a ‘responsibility’ and a ‘duty’. A year after the program, one participant reflected, ‘The glacier is rapidly changing because of climate change and it is my generation's task to help slow it down or reverse it’, while another noted, ‘I have never had such a feeling of comfort in the snow before Gulkana Glacier. Being surrounded by beauty made me realise how if we don't stand up for our environment we are going to be ruining the places that bring us comfort and joy’.

For several participants, protecting the glacier environment meant keeping it the same from the moment in time of their experience, with one participant worrying that their ‘children will probably see the landscape as something completely different than [she] was viewing in the moment’, while another stated, ‘it seems devastating that it would ever not be the same’. A study by Carey (Citation2007) is critical of this tendency to want to ‘re-set the clock’, suggesting that one of the problematic outcomes of the ‘endangered glacier’ narrative in common media is that it promotes an ‘ahistorical, paradoxical outcome by seeking to make glaciers static’ when, as geologically active features, they are not. However, although glaciers are indeed always dynamic and changing due to seasonal cycles and natural variability, the long-term trend of retreat and thinning (i.e. volume change) is indeed attributable to climate change. Although it may miss some of the subtleties of ecosystem dynamics, it can be argued that participants’ desire to see the glacier stay the same is generally compatible with a desire to see a climate in equilibrium.

Another critique of employing glaciers in climate change messaging hypothesises that using visuals such as glacier change photographs might actually fail in their purpose and drive disengagement, as the images show the discouraging reality that significant negative impacts have already been borne on the landscape (Doyle, Citation2009). Other research also cautions that while employing strong/shocking imagery can draw attention to the importance of the issue, it can also have a negative result on active engagement by provoking fear and leaving observers feeling helpless (O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Citation2009). However, while participants do express surprise and anxiety at the ongoing rate of ice loss, our findings suggest that the anxiety participants may feel over the state of the environment acts as motivation for action rather than despair, bolstered by a sense of relatedness to the landscape. This may be in part because of rich discussions during the program around ideas for individual and collective pro-environmental action.

One further critique is found again in the examination of the ‘endangered glacier’ narrative by Carey (Citation2007). The author details how presenting glaciers as a feature in need of saving can be precarious. He writes:

While it is vital to respond quickly to global warming and glacier melting, today's glacier narrative can be problematic because it contains underlying messages about what to save, how to save it, and for whom to save it. In short, popular glacier discourse can sometimes serve to: (1) legitimize and inspire Western intervention in glaciated areas; (2) portray local residents as passive victims suffering helplessly … and construe the world's glaciers as Western playgrounds and laboratories.

Here, the author raises important concerns connected to issues of colonialism. Altogether, we would suggest that the diversity of participants on Girls on Ice precludes inspiring a strictly Western intervention for saving ‘endangered glaciers’. Moreover, although the design of Girls on Ice curriculum is indeed rooted in Western epistemology, given the curriculum on science practice in the field, the focus remains primarily on understanding the two-directional influence of humans on landscape change (and vice versa) and on understanding ecosystem interconnectedness, elements that are not incompatible with U.S. Pacific Northwest indigenous perspectives on the natural world (Williams & Hunn, Citation2019).

6. Implications

Our findings offer several key implications for educators and education initiatives. To date, other research has drawn attention to some of the more challenging aspects of climate change that have been an obstacle for effective education on the subject. These include the facts that climate change: (a) is for many people a relatively invisible phenomenon compared to other environmental problems (e.g. an oil spill); (b) is a long-term problem, which means the consequences may not become fully apparent during one individual's lifetime (Schreiner et al., Citation2005) and (c) may be obscured by day-to-day weather variability, which acts to mask long-term trends (Shepardson et al., Citation2012). We propose that experiencing a glacier landscape helps to overcome these obstacles, by serving as imposing and hard-to-ignore visual evidence that transcends variability. In particular, witnessing the glacier size, and putting in context the scale of change in person was very impactful for participants. This implies that both formal and informal educators in northern and high latitude geographies globally, such as tour operators, interpreters or classroom teachers, may be able to support the development of relatedness and pro-environmental motivation by bringing learners to these landscapes and drawing attention to the changes that have occurred through time.

Several of our results also hold implications for developing elements of environmental identity beyond glacier landscapes. For example, we saw that developing a sense of relatedness to nature was strongly tied to gaining an understanding of how ecosystems are connected. This finding underscores studies that suggest that successful educational interventions for climate change engagement should focus less on gains in an individual's knowledge and more on designing program elements that, among other features, demonstrate interconnectedness, as this is more likely to result in people taking active steps to respond to climate change than simple knowledge acquisition (Allen & Crowley, Citation2017). Indeed, other research on climate change education in secondary schools promotes the importance of teaching about climate change through a systems perspective, based on the idea that bringing to light the connections between elements helps to better demonstrate impacts, and elucidates how humans both (a) contribute to climate change and (b) experience the consequences (Shepardson et al., Citation2012). Our results further underscore the importance of taking a systems approach to science learning within environmental education frameworks.

Next, our results are supported by a growing body of research that correlates personal experiences and belief in the reality of climate change. A review article by McDonald et al. (Citation2015) explores this research in terms of the dimensions across which individuals may feel psychologically distant from climate change impacts, whether by hypothetical distance (i.e. the likelihood of the impact occurring), geographic (spatial proximity to the impact), temporal (how soon the impact will occur) and/or social (how well connected one is to the people who will be affected). Our results suggest that in-person interactions with a landscape with visible, current and cumulative climate impacts help to alleviate each of these distances. Indeed, studies have linked belief to personal experience with weather events perceived to be the result of climate change, including drought (Haden et al., Citation2012), heat wave events (Joireman et al., Citation2010) or anomalous weather (Borick & Rabe, Citation2014). Notably, perceiving these events as unusual relies on an individual's memory of past events and is limited by the amount of time they have spent in that locale. On this note, few studies to date have examined the benefits from personal experiences with landscapes with visible signatures of long-term change. Two known exceptions are studies by Stapleton (Citation2015) on an overseas travel program for youth to visit climate change-impacted locations and people, and by Schweizer et al. (Citation2013) on the engagement of tourists in climate-impacted landscapes in U.S. national parks. Both were respectively found to motivate environmental action and increase salience, in line with the current study.

Several studies also highlight the importance of framing climate change discussions in terms of local rather than distant impacts, in order to leverage place attachment and to engage those who are closest to the issue (Hess et al., Citation2008; O’Neill & Nicholson-Cole, Citation2009; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2013). To date, however, these studies have focused primarily on locales in which people physically live, rather than visited sites to which people may develop place attachment after meaningful experiences there. Our findings appear to confirm known benefits, and support additional benefits, of an in-person visit to a visibly climate-impacted landscape.

One limitation we acknowledge is that this study was conducted with an all-female identifying group. This raises the question of how individuals of another gender may experience the climate change-impacted landscape differently, or conversely, how being part of an all-female group may have influenced the outcomes we report, vs. being in a mixed-gender group. In particular, we found that developing holistic understandings about ecosystem interconnectedness was a key part of developing a sense of relatedness, an important component of environmental identity. A review of studies on science learning notes that girls are indeed drawn to deep conceptual understandings rather than formulaic, rote learning and generally prefer topics that help others (Brotman & Moore, Citation2008). These characteristics align strongly with our findings. Conversely, boys exhibited greater preference for mechanistic understandings and could be more competitive in the learning environment (Brotman & Moore, Citation2008). To the extent that these distinctions apply to the participants in a given program, it may be that non-female-identifying youth take up these experiences with climate-impacted landscapes in different ways, resulting in different types or strength of connection to various aspects of environmental identity. Given literature on the outcomes of all-female programs, it may also be that experiencing the landscape in a mixed gender group could yield different outcomes. Future studies that specifically address the interplay of gender with environmental identity in outdoor education programming, including examining this in mixed group settings, would prove valuable in understanding whether experiences of a climate change-impacted landscape might vary by gender.

7. Conclusion

The present study explores the ways in which directly experiencing a climate change-impacted glacier landscape impacts environmental identity development in youth. We find that through spending eight days living on, traveling through, learning about and scientifically studying two glacier landscapes with visible, cumulative signs of climate change, many participants reported personal changes that can be described as environmental identity growth. Situating our analyses in the environmental identity model described by Clayton (Citation2003), emergent themes from interview and open-ended survey responses revealed gains in: relatedness to the natural environment, via better understanding ecosystem interconnectedness; and pro-environmental motivation, via a desire to share the landscape with others. Moreover, understanding the potential for two-directional impacts (negative and positive) of humans on the environment and witnessing the rate of glacier ice loss encouraged in tandem a deeper sense of relatedness and a desire to act pro-environmentally. These outcomes suggest that glaciers serve as a useful venue for deepening belief in the reality of climate change, by showcasing visible evidence of their accumulated demise since the onset of anthropogenic climate change. This overcomes several of the challenges that have to date been a hindrance for climate change education, including relative invisibility, obscurity among fluctuating weather patterns, and a lack of sense of scale. Interacting with a glacier also provided a personal connection to climate change impacts, whereas most research on personal connections to date have been focused on experiences of climate change-attributed weather events. We suggest that future outdoor education efforts may seek out opportunities for learners to experience glacier landscapes, emphasise elements of landscape interconnectedness, and/or provide direct experiences with other types of climate change-impacted landscapes as pathways to developing environmental identity, with the ultimate goal of improving citizen engagement in the climate crisis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of Girls on Ice for their open and thoughtful answers. We also thank the Girls on Ice instructors and program coordinator for help in facilitating the study, and Suzanne Perrin for conducting interviews. This work was supported by a Department of Interior Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center graduate fellowship awarded under Cooperative Agreement G17AC00213, by the National Science Foundation under award OIA-1208927 and by the State of Alaska (Experimental Program for Stimulating Competitive Research Alaska Adapting to Changing Environments award), and by the University of Alaska Fairbanks Resilience and Adaptation Program. We thank two anonymous reviewers for suggestions that have improved the manuscript. Finally, we gratefully acknowledge that the Girls on Ice programs take place on the traditional and unceded lands of the Ahtna people in Alaska, and the Nooksack, Coast Salish, and Nlaka’pamux people in Washington.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adkins, C., & Simmons, B. (2002). Outdoor, experiential, and environmental education: Converging or diverging approaches? ERIC Clearinghouse on Rural Education and Small Schools, AEL.

- Allen, L. B., & Crowley, K. (2017). Moving beyond scientific knowledge: Leveraging participation, relevance, and interconnectedness for climate education. International Journal of Global Warming, 12(3-4), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGW.2017.084781

- Aram, I. A. (2011). Indian media coverage of climate change. Current Science (Bangalore, 100(10), 1477–1478.

- Arnold, H. E., Cohen, F. G., & Warner, A. (2009). Youth and environmental action: Perspectives of young environmental leaders on their formative influences. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(3), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.3.27-36

- Berger, I. E. (1997). The demographics of recycling and the structure of environmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 29(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391659702900404

- Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (2007). Research for education: An introduction to theories and methods. Pearson.

- Borick, C. P., & Rabe, B. G. (2014). Weather or not? Examining the impact of meteorological conditions on public opinion regarding global warming. Weather, Climate, and Society, 6(3), 413–424. https://doi.org/10.1175/WCAS-D-13-00042.1

- Brotman, J. S., & Moore, F. M. (2008). Girls and science: A review of four themes in the science education literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 45(9), 971–1002.

- Cachelin, A., Paisley, K., & Blanchard, A. (2009). Using the significant life experience framework to inform program evaluation: The nature Conservancy's Wings & water wetlands education program. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(2), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.2.2-14

- Carey, M. (2007). The history of ice: How glaciers became an endangered species. Environmental History, 12(3), 497–527. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/12.3.497

- Carsten Conner, L. D., Perin, S. M., & Pettit, E. (2018). Tacit knowledge and girls’ notions about a field science community of practice. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/21548455.2017.1421798

- Chawla, L. (1998). Significant life experiences revisited: A review of research on sources of environmental sensitivity. The Journal of Environmental Education, 29(3), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958969809599114

- Chawla, L., & Cushing, D. F. (2007). Education for strategic environmental behavior. Environmental Education Research, 13(4), 437–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701581539

- Clayton, S. (2003). Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature. MIT Press.

- Crutzen, P. J., & Brauch, H. G. (2016). Geology of Mankind. In Paul J. Crutzen: A Pioneer on Atmospheric Chemistry and Climate Change in the Anthropocene (pp. 211–215). Springer.

- Culp, R. H. (1998). Adolescent girls and outdoor recreation: A case study examining constraints and effective programming. Journal of Leisure Research, 30(3), 356–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1998.11949838

- D'Amato, L. G., & Krasny, M. E. (2011). Outdoor adventure education: Applying transformative learning theory to understanding instrumental learning and personal growth in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 42(4), 237–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2011.581313

- De Vries, H., Elliott, M. N., Kanouse, D. E., & Teleki, S. S. (2008). Using pooled kappa to summarize interrater agreement across many items. Field Methods, 20(3), 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X08317166

- De Young, R. (2000). New ways to promote proenvironmental behavior: Expanding and evaluating motives for environmentally responsible behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 509–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00181

- Doyle, J. (2009). Seeing the climate? Ecosee: Image, Rhetoric, Nature, 279–298.

- Dyurgerov, M., & Meier, M. (2000). Twentieth century climate change: Evidence from small glaciers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(4), 1406–1411. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.97.4.1406

- Eames, C., Barker, M., & Scarff, C. (2018). Priorities, identity and the environment: Negotiating the early teenage years. The Journal of Environmental Education, 49(3), 189–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2017.1415195

- Fielding, K. S., & Hornsey, M. J. (2016). A social identity analysis of climate change and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Insights and opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 121. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121

- Fisher, S. R. (2016). Life trajectories of youth committing to climate activism. Environmental Education Research, 22(2), 229–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1007337

- Ford, P. (1986). Outdoor education: Definition and philosophy. Resources in Education, 21, 8.

- Gilbertson, K., Bates, T., Ewert, A., & McLaughlin, T. (2006). Outdoor education: Methods and strategies. Human Kinetics.

- Gilissen, M. G., Knippels, M.-C. P., & van Joolingen, W. R. (2020). Bringing systems thinking into the classroom. International Journal of Science Education, 42(8), 1253–1280.

- Haden, V. R., Niles, M. T., Lubell, M., Perlman, J., & Jackson, L. E. (2012). Global and local concerns: What attitudes and beliefs motivate farmers to mitigate and adapt to climate change? PloS one, 7(12), e52882. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052882

- Hess, J. J., Malilay, J. N., & Parkinson, A. J. (2008). Climate change: The importance of place. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 35(5), 468–478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.024

- Hinds, J. (2011). Woodland adventure for marginalized adolescents: Environmental attitudes, identity and competence. Applied Environmental Education & Communication, 10(4), 228–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533015X.2011.669689

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hungerford, H., & Volk, T. (1990). Changing learner behavior through environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 21(3), 8–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1990.10753743

- Joireman, J., Truelove, H. B., & Duell, B. (2010). Effect of outdoor temperature, heat primes and anchoring on belief in global warming. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 358–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.004

- Kari, J., & Smith, G. (2017). Dene Atlas. The web Atlas of Alaskan dene place names, version 1.2. February 1.

- Kolb, D. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press.

- Leinhardt, G., & Crowley, K. (2002). Objects of learning, objects of talk: Changing minds in museums. Perspectives on Object-Centered Learning in Museums, 301–324.

- Leiserowitz, A. A. (2005). American risk perceptions: Is climate change dangerous? Risk Analysis: An International Journal, 25(6), 1433–1442. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00690.x

- Liddicoat, K. R., & Krasny, M. E. (2014). Memories as useful outcomes of residential outdoor environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 45(3), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2014.905431

- Masson-Delmotte, V., Zhai, P., Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Skea, J., Shukla, P., & Waterfield, T. (2018). IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (Technical report). World Meteorological Organization.

- McDonald, R. I., Chai, H. Y., & Newell, B. R. (2015). Personal experience and the `psychological distance’ of climate change: An integrative review. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 44, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.10.003

- McGuire, N. M. (2015). Environmental education and behavioral change: An identity-based environmental education model. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 10(5), 695–715. https://doi.org/10.12973/ijese.2015.261a

- Meehan, C. R., Levy, B. L., & Collet-Gildard, L. (2018). Global climate change in US high school curricula: Portrayals of the causes, consequences, and potential responses. Science Education, 102(3), 498–528. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21338

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. John Wiley & Sons.

- Mogk, D. W., & Goodwin, C. (2012). Learning in the _eld: Synthesis of research on thinking and learning in the geosciences. Geological Society of America Special Papers, 486, 131–163.

- Naess, A. (1973). The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement. A summary. Inquiry, 16(1-4), 95–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00201747308601682

- National Generation Science Standards Lead States. (2013). Next generation science standards: For states, by states. National Academies Press.

- Ojala, M. (2015). Climate change skepticism among adolescents. Journal of Youth Studies, 18(9), 1135–1153. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2015.1020927

- O'Neill, S., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). “Fear won't do it”: promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

- Palmer, J. (2002). Environmental education in the 21st century: Theory, practice, progress and promise. Routledge.

- Roe, G. H., Baker, M. B., & Herla, F. (2017). Centennial glacier retreat as categorical evidence of regional climate change. Nature Geoscience, 10(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2863

- Rosenberg, M. (1981). The Self-concept: Social product social force. In M. Rosenberg & R. H. Turner (Eds.), Social psychology: Sociological perspectives (pp. 593–624). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2011). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage (Atlanta, GA).

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2013). Personally relevant climate change: The role of place attachment and local versus global message framing in engagement. Environment and Behavior, 45(1), 60–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916511421196

- Schreiner, C., Henriksen, E. K., & Kirkeby Hansen, P. J. (2005). Climate education: Empowering today's youth to meet tomorrow's challenges. Studies in Science Education, 41(2005), 3–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057260508560213

- Schweizer, S., Davis, S., & Thompson, J. (2013). Changing the conversation about climate change: A theoretical framework for place-based climate change engagement. Environmental Communication: A Journal of Nature and Culture, 7(1), 42–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2012.753634

- Shepardson, D. P., Niyogi, D., Roychoudhury, A., & Hirsch, A. (2012). Conceptualizing climate change in the context of a climate system: Implications for climate and environmental education. Environmental Education Research, 18(3), 323–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.622839

- Stapleton, S. R. (2015). Environmental identity development through social interactions, action, and recognition. The Journal of Environmental Education, 46(2), 94–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2014.1000813

- Stapp, W. (1969). The concept of environmental education. Environmental Education, 1(1), 30–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00139254.1969.10801479

- Stevenson, K. T., Peterson, M. N., Bondell, H. D., Moore, S. E., & Carrier, S. J. (2014). Overcoming skepticism with education: Interacting influences of worldview and climate change knowledge on perceived climate change risk among adolescents. Climatic Change, 126(3-4), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1228-7

- Streule, M., & Craig, L. (2016). Social learning theories – An important design consideration for geoscience fieldwork. Journal of Geoscience Education, 64(2), 101–107. https://doi.org/10.5408/15-119.1

- Tanner, T. (1980). Significant life experiences: A new research area in environmental education. The Journal of Environmental Education, 11(4), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1980.9941386

- Tilbury, D. (1995). Environmental education for sustainability: Defining the new focus of environmental education in the 1990s. Environmental Education Research, 1(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462950010206

- Vujovic, J. O. S. (2014). Further education training geography teachers’ knowledge and perceptions of climate change and an evaluation of the textbooks used for climate change education (Unpublished master's thesis). University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Wals, A. E., Brody, M., Dillon, J., & Stevenson, R. B. (2014). Convergence between science and environmental education. Science, 344(6184), 583–584. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1250515

- Wattchow, B., & Brown, M. (2011). A pedagogy of place: Outdoor education for a changing world. Monash University Publishing.

- Whittington, A., Aspelmeier, J. E., & Budbill, N. W. (2016). Promoting resiliency in adolescent girls through adventure programming. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(1), 2–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2015.1047872

- Whittington, A., Mack, E. N., Budbill, N. W., & McKenney, P. (2011). All-girls adventure programmes: What are the benefits? Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/14729679.2010.505817

- Williams, C. C., & Chawla, L. (2016). Environmental identity formation in nonformal environmental education programs. Environmental Education Research, 22(7), 978–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1055553

- Williams, N. M., & Hunn, E. S. (2019). Resource managers: North American and Australian hunter-gatherers. Routledge.