ABSTRACT

While students tend to enjoy their science learning at a young age, as they mature, they tend to distance themselves from science, becoming less motivated to engage with science and holding negative attitudes towards science. In parallel, a career choice in science often begins to develop during early adolescence. To understand how the environment and students’ inner worlds shape the development of their self-positioning in relation to science, this longitudinal study followed nine adolescents, aged 10–14, over 3 years, in and out of school, and created nine individual stories describing these participants’ self-positioning in relation to science, and how these positions changed, from their perspective, over time and contexts. We found some common experiences that played a role in the participants’ self-positioning in relation to science. In several of these experiences, the longitudinal nature of this study became apparent. This study highlights the complexity of adolescents’ self-positioning in relation to science and how these positions change over time.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The public’s engagement with science and knowledge of science are issues of enduring interest to the science community, governments and science education policy makers (Ainley & Ainley, Citation2011; Archer et al., Citation2010; Pattison & Dierking, Citation2019; Scholes & Stahl, Citation2020). Citizens who understand science can participate in public debates over the central socio-scientific issues that are the grand challenges of our time (OECD, Citation2000; Shin et al., Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2019), such as COVID-19 vaccinations and climate change. While most students enjoy their science learning at a young age, as they grow older, they tend to become less motivated to engage with science, their interest in science tends to decline and they sometimes develop negative attitudes towards science (Archer et al., Citation2010; Jenkins, Citation2019). While the influence of many environmental factors on students’ engagement with science has been investigated (e.g. Basu & Barton, Citation2007; Edy et al., Citation2019; Vedder-Weiss & Fortus, Citation2013; Wood, Citation2019), very few studies have taken a longitudinal approach (Bricker & Bell, Citation2014), and even fewer have, to the best of our knowledge, closely followed young adolescent over several years, in and out of school. This study does just that and attempts to describe the young adolescents who participated in this study as whole persons, students, friends, brothers or sisters, and children of their parents, by creating nine individual stories that shed light on their self-positioning in relation to science and the ways in which these positions changed over time and contexts. The question that guided this study was: How do young adolescents describe their self-positioning in relation to science and science learning in and out of school?

Theoretical background

Self-positioning and personal stories

Self-positioning always takes place in the context of a particular event. Deliberate self-positioning occurs in any conversation in which the person wants to express their identity (Arnold & Clarke, Citation2014). Arnold and Clarke (Citation2014, p. 746) described positions as ‘locations from which persons act in a conversation and, together with conversational storylines, make the meaning of action relatively determinate’. Self-positioning is done in three main ways: by comparing one’s choices and behaviour to those of others, by referring to one’s unique perspectives, or by referring to events in one’s biography (Harré & Van Langenhove, Citation1991). For example, Protacio (Citation2019) provided three stories describing how three students’ self-positioning in relation to reading affected their social interactions and their past histories. She shows how self-positioning led to positive or negative attitudes towards reading and in some cases towards academic learning in general. Positioning is also important for teachers: for example, Hazari et al. (Citation2015) showed how the positioning of a physics teacher influenced student engagement in a physics class. The self-positioning of students can be revealed through narrative inquiry that recreates the stories of the students, their personal experiences, making it possible to convey their attitudes and personal perspectives, and how these develop with time.

People are storytellers and one of the ways in which we experience the world is through stories. The essence of a story is the sharing of the personal experiences of the ‘main character’ of the story (Swidler, Citation2000). Exploring people’s stories is one way of understanding people’s experiences (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990; Yerrick et al., Citation2011). Narrative inquiry has become common in education research (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990; Varelas et al., Citation2012; Varelas et al., Citation2015) and serves as a tool for revealing and understanding people’s personal experiences, and through them their positions. Students’ self-positioning in relation to science can be understood through their stories, in which teachers, parents, other students and other significant adults are important and meaningful characters in the narrative, which occurs in different settings in and out of school (Connelly & Clandinin, Citation1990).

Adolescent’s self-positioning in relation to science

Self-positioning in relation to science is related to science identity, as described by Hazari et al. (Citation2010) and Carlone and Johnson (Citation2007). However, we view it as being more limited, as being the individual’s personal (and often temporary) position in relation to science, while science identity also involves the recognition of others: ‘ … one cannot claim an identity all by oneself; being “somebody” requires the participation of others’ (Carlone & Johnson, Citation2007, p. 1190). We do not claim that self-positioning occurs in a vacuum and is independent of others. Rather, we view young adolescents’ self-positioning in relation to science as a shifting outcome of many processes that involve several personal traits and environmental factors. Young adolescents seldom know clearly who they are. They often have ideas what they would like to become and what they don’t want to be, but it is rare to find a young adolescent who has a clear identity (Erikson, Citation1994). They have positions on many topics and in relation to many possible professions, but these positions are still far from a defining identity. Self-positioning is part of the process of developing an identity.

We felt that the similarity between self-positioning in relation to science and science identity allowed us to draw upon the research on science identity in defining the personal traits and environmental factors that needed to be considered when studying self-positioning. Studies on science identity have conceptualised science identity in four dimensions (e.g., Carlone & Johnson, Citation2007; Hazari et al., Citation2010): (A) performance – a belief in one’s ability to carry out tasks in science, (B) competence – a belief in one’s ability to understand science content, (C) interest – interest in science and a desire to understand science and (D) recognition – recognition by others as being a good science student. We view the first three dimensions as personal traits that influence self-positioning and they change as one’s position in relation to science develops. The first two are different aspects of self-efficacy in science (Dorfman & Fortus, Citation2019), so we combined them and called them by that name from this point on. As self-positioning is done not only in relation to oneself but also in relation to science as something external to oneself (Harré & Van Langenhove, Citation1991), we added a third personal trait, participants’ attitudes towards science and scientists. The fourth dimension, the recognition by others was, in our opinion, too limited to describe the environmental factors that help shape young adolescents’ self-positioning in relation to science, so we broadened it to include not only the recognition by others (parents and siblings, peers, science teachers, instructors in informal settings), but in general the experiences of young adolescents at home, at school, with friends and in after-school programs. Personal traits and environmental factors are interrelated: the environmental factors influence the personal traits while the personal traits influence the way the environment is perceived and responded to.

Focusing on these personal traits and environmental factors allowed us to create broad and rich pictures of the ways the participants positioned themselves about science and how these positions changed over time. Not all the environmental factors and traits we considered made their presence equally felt for each participant in the data we collected.

Personal traits

Self-efficacy in science. Self-efficacy is an expectancy about one’s capabilities to understand certain ideas or perform given tasks (Schunk & Zimmerman, Citation2006). The self-efficacy of students in science has a great influence on their enjoyment of science learning (Ainley & Ainley, Citation2011) and is a strong predictor of their interest in science (Okafor & Okpli, Citation2020) and their aspirations to major in science or seek a career in science (Avargil, Kohen, & Dori, Citation2020; DeWitt et al., Citation2013). Self-efficacy influences one's self-position towards science: high self-efficacy can support a positive position in relation to science, providing the confidence to pursue and engage in scientific studies, while low self-efficacy may lead to a negative position, leading to a rejection of science and favouring other activities. Girls tend to exhibit lower self-efficacy in science than boys (Foeken, Citation2018). This emphasises the importance of teaching science in ways that can enhance students’ self-efficacy in science (Archer et al., Citation2010).

Interest in science. Interest refers to the psychological state of being engaged or the inclination to reengage with particular objects, events or ideas over time, and is often called individual interest (Hidi & Renninger, Citation2006). Interest is a motivator that is content specific (Deci, Citation1992). Schools often have a large influence on students’ interest in science as much of students’ exposure to scientific knowledge takes place at schools (Barmby et al., Citation2008; DeWitt & Archer, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2020; Wood, Citation2019). Interest in science tends to decrease as students grow older (Krapp & Prenzel, Citation2011). Showing interest or disinterest in science is one way of expressing one's self-position about science.

Attitudes towards science and scientists. Students often think that science in school is not the science that adults deal with or do in their careers (Barmby et al., Citation2008; El Takach & Yacoubian, Citation2020), especially if they are engaged with science during their leisure time. They may understand the importance of science but not necessarily what scientists do (DeWitt et al., Citation2013). The mental image that many adolescents have of scientists is often unappealing. On the one hand, science is often thought of as a masculine subject, being commonly described by masculine adjectives (Makarova et al., Citation2019; Scholes & Stahl, Citation2020) – this does not help make it attractive to girls. On the other hand, the nerdish image of scientists and the idea of being associated with a nerdish group can lower students’ desire to engage with science. Students who are concerned with how potential romantic partners may think of them are less likely to engage in science (DeWitt et al., Citation2013; Starr, Citation2018).

Environmental factors

Parents and family. Students’ families can offer supportive experiences and foster the belief in their children that doing science is a possibility for them (Gilmartin et al., Citation2006; Kewalramani et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). Parental involvement can have an important influence on academic development and career choice in science (Aschbacher et al., Citation2010; DeWitt et al., Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2020). An accessible family member that works in science or a science-related profession can inspire and encourage interest in the same field (Franse et al., Citation2020; Gilmartin et al., Citation2006).

Many families encourage their children to study science in the first years of high school, but with time, their support shifts toward the goal of finishing high school and away from studying science (Aschbacher et al., Citation2010). If students experience a disappointment in science, their parents have a critical role to help keep the student engaged in science despite the disappointment (Aschbacher et al., Citation2010; Hoferichter & Raufelder, Citation2019).

Peers. Young people today are less focused on ‘what do you want to do’ and more oriented towards ‘who do you want to be’ (Barmby et al., Citation2008). The socio-cultural stigma that marks ‘science people’ as geeks or nerds promotes the disengagement of some from science (Archer et al., Citation2010; Kelly, Citation2019; Starr, Citation2018; Zimmerman, Citation2012). On the other hand, when students feel that their peers appreciate their ability to understand science, their motivation to continue learning science grows (Dorfman & Fortus, Citation2019). The influence of peers on students’ motivation for science grows with age (Wood, Citation2019). This is especially true of low-SES boys whose relations with their peers often moderate other influential relations (Touitou, Citation2016). Caspi et al. (Citation2020) showed that the peer group has a strong influence on student’s enrollment in after-school science programs. Peer support can help adolescents maintain or strengthen positive positions towards the sciences.

Science teachers and school science. Science teachers have a large impact on students’ interest in and attitudes toward science, as much of students’ exposure to science occurs at schools (Barmby et al., Citation2008; Wood, Citation2019). There is conflicting evidence regarding the relations between the enjoyment of science classes and interest in science. On one hand, some studies have found that students who enjoy science lessons don’t differ from other students regarding their interest in science (Archer et al., Citation2010; Edy et al., Citation2019; Wood, Citation2019), while on the other hand, other studies have indicated that enjoyment of classroom lessons is a good predictor which students will choose to continue studying science (Ainley & Ainley, Citation2011; Aschbacher et al., Citation2010). Wood (Citation2019) argues that the science teacher is the most important and influential factor in students’ involvement in science classes, and for a science class to stimulate engagement, students should perceive that there is a positive emotional climate together with a warm, caring and interpersonal relationship with the teacher.

Much of elementary school science teaching is interactive and focuses on visually accessible concrete phenomena. As students grow older, school science becomes more abstract and perceived as a subject that is only for the cleverest students (Archer et al., Citation2010; María & José, Citation2020). However, students tend to expect that school science will be student-centred and exciting, not paper and pen based, leading to incompatibility between students’ expectations and reality (Archer et al., Citation2010).

Learning science in informal settings. Science learning occurs in three settings: formal learning (at school), informal learning (after-school activities) and non-formal learning (during leisure time). Students do not spend as many hours in school as we may think. Averaged over the entire year, including holidays and vacations, a student is at school about 4 hours a day (Feder et al., Citation2009). Informal and non-formal influences may play a greater role than formal settings in shaping students’ self-positions toward science (Caspi et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2019). Students that are interested in science often engage with science in their free time (Archer et al., Citation2010). To increase students’ engagement with science in general, links should be forged between the different settings by enhancing the awareness of the formal, informal and non-formal settings of what is happening in the others (Dierks et al., Citation2016).

Summary and research question

Many factors influence the way young adolescents position themselves in relation to science and choose and how these positions change. It is important to understand the reasons and the factors that shape these positions and how these positions play a role in students’ engagement with science. This understanding can help us adjust learning environments in school and after school to better suit the interests and needs of young adolescents in relation to science. Few studies have taken a longitudinal approach (Bricker & Bell, Citation2014), and even fewer have followed their participants in and out of school. This study attempts to describe its participants not just as students, but as friends, brothers or sisters, and children of their parents. The research question that guided this study was: How do young adolescents describe their self-positioning in relation to science and science learning in and out of school?

Methods

Procedure

In the second half of the 2016–17 school year, all grade 4 and 5 students with parental approval in a single Israeli elementary school (ES) completed, as part of a larger study, a survey mapping their effect towards science. Based on the results of this survey, students representing a range of effect towards science were interviewed. Science classes were repeatedly observed. At the start of the 2017–18 school year, a subset of the students who were interviewed (now in grades 5 and 6) – the focus group – obtained expanded parental permission that allowed us to visit them at home and join them in their after-school programs. They were re-interviewed approximately every six weeks throughout that academic year and throughout the 2018–19 academic year, when the oldest of them had already transitioned to the single local junior high school (JHS), for about 30 min each time. shows the structure of the study. All names are anonymised.

Table 1. Study structure.

Sample

The study was conducted at an Israeli ES and an adjacent JHS. Almost all the students in the ES continue onward to the JHS. The average number of students per class in both the ES and the JHS was 25–26 (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016). Between the 2016–18 school year, all data collection was conducted at the ES; in the 2018–19 school year, data were collected from both schools.

Students

Ninety-one fourth- and fifth-grade students, aged 10–14, who returned signed consent forms, completed an affective mapping survey (Dorfman & Fortus, Citation2019; Vedder-Weiss & Fortus, Citation2011). The survey allowed the students to get familiar with us. Sixty-two of the students, representing a wide range of affective characteristics, were interviewed.

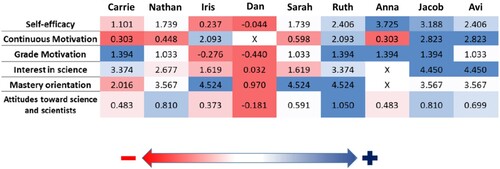

Based upon these interviews, the survey, 3.5 months of classroom observations, and stated willingness to be part of a longitudinal focus group, we invited 15 fourth-grade and 15 fifth-grade students that presented a variety of characteristics and their parents to be part of a focus group, which involved having us continue to interview them, and visit them at their homes and their after-school activities. Nine agreed, seven from fourth grade and two from fifth grade. In the second year of the study, two of the fifth-grade students left the study; in parallel we recruited two other students from the same grade to join the focus group. represents the diverse affective characteristics of the nine focus students.

Figure 1. Affective characteristics of the focus students at the start of the study.

Note: The values result from a Rasch analysis done on the data of all the students who answered the survey. The colours are a gradient of positive blue and negative red. As an affective characteristic becomes more positive, its hue becomes bluer, or redder as the characteristic becomes more negative. White cells are in the middle range of the results. Cells marked with X represent values of a characteristic that couldn’t be Rasch-calculated for a particular child.

Teachers

Due to space limitations, the full description of the students’ science teachers is presented in online Appendix A.

Parents

The parents of each of the focus students were interviewed twice. All families had similar socioeconomic statuses, medium-high (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Citation2016).

After-school programs

Three times in each year of the study, we visited the after-school science programs in which the focus students participated. During these visits, we interviewed the instructors and observed the focus student(s). Due to space limitations, the full description of these programs is presented in online Appendix B.

Instruments

The study was conducted using a multiple narrative case study (Barton, Citation2001; Bell et al., Citation2013; Wenner & Settlage, Citation2015), drawing upon observations in and out of school, interviews with children, their parents and other significant adults, and the researchers’ field notes.

Observations

During the 2016–17 school year, we observed the ES science lessons over 3.5 months, gathering information about the classroom engagement and attitudes of all the potential focus group students. These observations were used together with the affective mapping survey and the interviews, to select potential members of the focus group.

Interviews

Students. The first student interviews were conducted to create mutual acquaintance – us with the students and the students with us. Later, the focus students were asked to elaborate on their areas of interest in general, towards science and science education. We began to understand the students from different angles. These conversations were conducted approximately every 6 weeks. An additional interview was held after a classroom event that was deemed to be possibly significant to the development of the student’s attitudes and motivation towards science. Interviews were held after each visit to an after-school program to understand what occurred, from the student’s perspective. Our questions were mostly open-ended, for example: ‘What happened today?’ ‘What did you think of the events?’ ‘How did it make you feel?’ Ongoing informal discussions were held with the students during school breaks (Cros et al., Citation1986). The interviews addressed all dimensions of self-positioning mentioned earlier, both personal traits and environmental influences. All the interviews were audio recorded, with the students being asked for their consent each time. Every interview was transcribed. Utterances were written as they were spoken. All the relevant information was written in each student’s section in the research journal.

Parents. Once a year we interviewed each focus student’s parents, asking about their background, their attitudes towards school, towards science and science education at the school, and in relation to their child(ren). Families who had no interest in science were asked to expand on their fields of interests. No notes or recordings were made of these interviews to allow an open and relaxed atmosphere. Immediately after each conversation, we recorded ourselves repeating the main points of the conversation, which were then transferred to the research journal.

Teachers. Due to the teachers’ concerns about the possible influence of the study on their workplace, none of them were formally interviewed, but just chatted informally, usually during their breaks between classes. These conversations dealt mainly with the school’s administration and questions they had about the syllabus they were supposed to teach.

After-school instructors. Nine after-school instructors were interviewed about the program they led, its goals and approach, and their impressions of the relevant focus students who participated in their program. This information was added to the research journal.

Research journal

A journal was used to keep track of daily events and identify incidents and utterances that might be of significance. Every focus student had an individual section in the journal, where all the material related to the student was recorded in chronological order.

Analyses

At the end of the data collection, we marked, in each focus student’s section, segments of conversations that were significant or repetitive (Barton, Citation2001; Bricker & Bell, Citation2014). Specifically, we marked positive or negative turning points that had occurred during the years in relation to the sciences. All the marked parts were then put into categories such as family, attitudes to science, school, future profession, etc. (Bricker & Bell, Citation2014). The categories were chosen according to the content of the conversations we had with the children, such as repetitive themes, as well as topics that clarified their participation and interest in or lack of interest in the sciences. This action is consistent with the description of the use of ‘paradigmatic narrative inquiry’ (Polkinghorne, Citation1995): ‘Narrative can denote any prosaic discourse, that is, any text that consists of complete sentences linked into a coherent and integrated statement’ (Polkinghorne, Citation1995, p. 6).

We then did a ‘narrative smoothing’, which means filtering and removing phrases and comments that were difficult to understand: ‘Narrative smoothing is an action in which elements which do not contradict the plot, but which are not pertinent to its development, do not become part of the research result, the storied narrative’ (Polkinghorne, Citation1995, p. 16).

We wrote paragraphs that summarised the information that appeared within the quotes and the conversations. Within the paragraphs, certain elements were emphasised to clarify their choice. Then we combined the paragraphs into stories ‘that combine a succession of incidents into a unified episode’ (Polkinghorne, Citation1995, p. 17). The stories were intended to support readers in understanding the context of time, space and individuality of each student. Through the stories, we tried to convey the students’ full experience studying science in formal, informal and non-formal learning environments. The stories convey the positive and negative experiences that each student went through, most in the context of studying science but not all, experiences that shaped their attitudes towards science (Bricker & Bell, Citation2014). The final stories convey the personal experiences of nine adolescent students and how their self-positioning in relation to science changed over time. These stories stand on their own and aim to reflect the individual student’s experiences.

Finally, we extracted motifs from the stories. Since narrative inquiry aims to understand human action (Polkinghorne, Citation1995) the focus of the motifs was on the factors and influences that contributed to the children’s self-positioning toward science and science studies. In practice, we identified recurring issues that came up in most of the stories or all of them and were related to self-positioning toward science and science studies. We created summaries of the stories that included each story’s motifs.

The validation approach we used was ‘argumentative validation’. Once a month, the two authors discussed the main issues that arose from each student in the focus group. In this conversation, we reviewed the interviews and raised questions and topics for future interviews with the students. Each author suggested possible coding categories for student’s story. We argued over our choices and made adjustments and changes until a full agreement was reached. The stories were prepared by the first author, then reviewed and critiqued by the second author. Again, changes were made until the narratives had full joint approval. The motifs presented are only those on which we fully agreed and that appeared to be most significant. (Fischer & Girwidz, Citation2022; Mayring, Citation2016).

After all the stories were written, each of the two authors independently ranked how each of the participants changed throughout the course of the study, in each of the Personal Traits (self-efficacy in science, interest in science, and attitudes towards science and scientists) and their attunement to various Environmental Factors (parents and family, peers, science teachers and informal settings). The ranking was done for each year as High, Medium and Low and was done for each participant in comparison to themselves, in light of the changes they underwent over the three years of the study. These rankings were used to create , which provides a comprehensive overview of all the stories. The rankings of both authors were compared and where there were disagreements, a discussion was held until a joint agreement was reached.

Table 2. Summary of trends in each of the stories.

Results

Nine stories were written, one for each focus student who participated throughout the entire study. Each of the stories is 25–30 pages long and presents many aspects about each child’s life and their self-positioning, not only those directly related to science. All names presented are anonymised. Due to space limitations, we present only the summaries of two stories in , all the other story summaries are presented online, in Appendix C, while Ofek-Geva (2021) presents the full stories in Hebrew. In the following section, we present motifs we identified from all nine stories and give excerpts from the stories that are characteristics of the motifs.

To provide a comprehensive overview of the stories of all the participants in the study, presents the findings of each year broadly. We urge readers to read the stories of the participants to gain a deeper, richer, and more complete understanding.

Motifs that emerged from the stories

We present four motifs, each accompanied by at least two excerpts from the interviews.

After-school science programs

The students who participated in the afterschool science programs felt that science, as it was taught in school, was not ‘real’ science. The afterschool classes programs allowed students to engage in science actively and experimentally, different from the way it was done in the classroom.

‘Natalie [The science teacher] is more … they … the instructors [in the after-school program] … they seem to understand more about science than Natalie. It seems to me that Natalie does not … .’ (Natan)

‘Rose [The science teacher] just cannot teach. When talking to Rose, you suddenly notice that there is a circle of children asking her for help. I don’t say she doesn’t do it well, it’s difficult for her and we are a very problematic class’ (Sarah)

Do you think you learn science in school?

‘Not in this school.’

Do you learn science at Science for Everyone?

‘What do you think?!!!’

I don’t know, what do you think?

‘Obviously!’ (Sarah)

Becoming an adolescent

The children were not static, they changed and developed throughout the study in relation to science learning and other things. In all the children, emotional and physical development was seen. A distancing from non-formal science and exploration was seen in those children who had spontaneously engaged in science at home during their leisure time at the beginning of the study. The identification of this motif is the direct result of the longitudinal nature of the study, since it focuses on the maturation of the participants.

‘She no longer does experiments at home; science is a smaller part of her life’ (Sarah’s parents).

‘It’s harder for me now to concentrate on the lessons’.

Why do you think it's like this suddenly?

‘I don’t know … adolescence, don’t know’.

Why do you say that, according to what? Why adolescence?

‘Because that’s what's been happening lately’.

Do you feel it?

‘It’s getting harder and harder to get up in the morning’.

Do you feel like you're growing up?

‘I don’t know, I feel I simply don’t have the energy to do things’. (Jacob)

The science teacher

The science teacher had a broad influence on science learning and the students’ attitudes towards science learning. All the students were referred multiple times to their science teachers. All the students indicated that their teachers’ behaviour, caring and fairness were of high importance to them, and that the way the teacher behaved was a significant factor influencing their attitudes towards the teacher and towards science.

‘Science last year was really bad; I was really angry. She was completely disrespectful to me. It was horrible. I just said, she [the teacher] isn’t showing me respect so I won’t show her respect, I won’t study … Luckily for me, she stayed in elementary school, and I continued to junior high’. (Avi)

Tell me about science this year.

‘She [the science teacher] does unfair things.’ (Anna)

How was your report card?

‘Great. Natalie wrote that I should participate more, and then my mom read it and asked me why I wasn’t participating’

What do you think about that?

‘I do participate. Natalie wrote that I should participate more, but how am I supposed to participate more if she doesn’t let me speak or ask questions when I raise my hand?’ (Sarah)

Which classes do you prefer in science, in elementary or junior high school?

‘In junior high school’.

Why? What is the difference?

‘Ahhh experiments, and the teachers take us more seriously’. (Jacob)

What is remembered

After 3–4 months, the students usually did not remember the content they had been taught. However, they did remember, even years later, the positive and negative experiences they had in science class.

What do you think about science studies at school in the fourth and fifth grades?

‘They were okay, 5th was harder, 4th was okay’.

Can you be specific, what did you like to study and what did you not like to study?

‘I don't remember anymore; I remember we learned about ahhh [quiet]. I forgot what it's called’.

Can you describe it?

‘It's about animals’.

What grade was it in?

‘In 4th, I had fun because we had a project presentation. Everyone prepared a presentation’. (Iris)

Do you remember what you learned in science this year?

‘Barely … ’

And before that?

‘I don’t remember; that was a while ago’.

And are there any other things you did with Rose this year?

‘Yes, we also went outside. I don’t remember what activity we did, but it was with a basketball. We had to check how many degrees it takes to throw the ball up. We measured the temperature. Like a meter like that which is high, and it checks the weather’. (Dan)

Discussion

Previous research has demonstrated that while students tend to enjoy their science learning at a young age, as they grow older, they tend to position themselves further from science, becoming less motivated to engage with science and sometimes expressing negative attitudes towards science (Archer et al., Citation2010). This study emphasises that every student is unique, as can be seen in , there is likely no magic formula that will lead all students to adopt positive positions in relation to science (Farland-Smith, Citation2019). As the participants in our focus group represented a range of affective characteristic (see ), the motifs we identified do not reflect personal traits that appear to be related to self-positioning in relation to science. What we found were common personal experiences that re-appeared with all our participants and that played a role in their self-positioning in relation to science: the physical and emotional experience of becoming an adolescent, what they remembered from their science classes, the experience of going to an after-school program, and the experience of interacting with the science teachers. In several of these motifs, the longitudinal nature of this study became apparent, because they deal with changes to the ways the participants thought and felt, or how external changes affect their self-positioning.

Becoming an adolescent: self-positioning oneself further from science

Simply becoming an adolescent affects one’s position in relation to science (Massey et al., Citation2008). Adolescence is a period, usually between 11 and 18, during which individuals undergo physical, mental, emotional and social processes that shape their selves and their self-positioning in relation to many spheres of life (Blakemore, Citation2012; Ebner et al., Citation2014). One of the most significant changes that occur during adolescence is becoming more attuned to the peer group (Blakemore, Citation2008), as can be seen in for Natan, Sarah, Carrie, Ruth, Jacob and Avi. This is a challenging period, mainly for the adolescents themselves, but also for their parents, and their surrounding environment, including their teachers in school. Over the 3 years in which we became personally acquainted with this study’s participants, we saw each of them change and develop, we saw how adolescence affected them and their self-positioning towards science and scientists. Their self-positions changed according to their personal interests, their relations with their peers, parents and siblings, and their experiences of learning science.

The participants who had engaged in spontaneous experiments at home or who had participated in after-school science classes did not want to continue this as they matured, even though they had enjoyed them. The children explained that doing things with their friends took up a lot of time and this was why they did not engage in experiments anymore or go to these classes. Zimmerman (Citation2012) wrote of a 12-year-old girl who also distanced herself from science for similar reasons. On the other hand, Tan and Barton (Citation2008) identified sixth-grade students whose engagement with and interest in science increased as the year progressed, due to the influence of a good teacher. A similar effect can be seen in Avi’s story.

Massey et al. (Citation2008) emphasised that adolescents are more engaged in what is going on between them, inside their peer group, than at any other age. It is important that children experience and gain pleasant and meaningful interactions with science before the onset of adolescence. This increases the chances that they will return to a pursuit of science after ‘acclimatisation’ to adolescence (Ryan, Citation2001).

Adolescence is accompanied by physiological effects, some of which were described by the children in this study, such as lassitude, difficulty getting out of bed, and emotional ups and downs. These are natural processes that are not under the control of the children, and many do not understand what is happening to them. Shifting feelings, attitudes, interest and self-efficacy in studying science during adolescence are natural as well; they should be viewed as a natural maturation process (Baumeister et al., Citation2001; King et al., Citation2015). Teachers, researchers and policymakers should not ignore this (Carskadon et al., Citation2004; Wolfson & Carskadon, Citation2003) and be mindful of the shifting physiological, psychological and social states of adolescents (Hahn et al., Citation2012; Wolfson & Carskadon, Citation2003). For example, Wahlstrom (Citation2002) showed that delaying the start of school by 65 minutes led to fewer students falling asleep during the first period, fewer children being sent home due to health issues, more children eating breakfast before coming to school, a calmer atmosphere in the school, and more pleasant student behaviour at lunchtime.

Adapting the education system to the physiological changes that adolescents experience may allow them to cope with the demands of the schools and at the same time adjust and develop physiologically in an optimal way.

After-school science programs: fostering student resilience to challenges in school science

During the first and second years of the study, five students (Natan, Sarah, Carrie, Anna and Avi) participated in after-school science programs. Not all these students had a pre-existing interest in science. These students talked about science differently than their four peers who did not go to after-school science activities. These programs affected their self-positioning in relation to science, with an overall positive trend. They explained that the afterschool programs were different from regular science classes, and that they allowed them to engage with science actively and experimentally. Compared to their peers who were not in after-school programs, they had greater tolerance for disappointing experiences in the science classroom, but not towards the teacher’s conduct and attitude.

Thomasian (Citation2011) highlighted the benefits of after-school programs, such as connecting science knowledge to daily life and careers and expanding science skills (Young et al., Citation2019). Others have shown that participants in these programs show greater interest in science, even years after participating in the programs (Bell et al., Citation2012; Burke, Citation2020). It seems, therefore, that children should be encouraged to go to after-school science programs.

Archer et al. (Citation2015) stated that children who attend after-school programs tend to come from higher science capital homes. We saw this trend as well. Banks et al. (Citation2007) recommended ‘using’ afterschool science programs to reduce gaps that may originate from home. This exposure can balance what happens in the classroom and give children a different experience and a broader horizon for future science studies. However, the admission tests for some of the programs that participated in our study deterred some children and had a negative impact on some of those who did not pass the tests; we recommend, if possible, making these programs available to all students without requiring them to pass an admissions exam.

Good and bad experiences: what is remembered

After 3 to4 months, our participants mostly did not remember what was taught in class (Papadimitriou, Citation2004). Investigations of the memories, experiences and emotions of students studying science (Cohen et al., Citation2021; King et al., Citation2015) highlight that students remember the material that was studied if they are linked to positive experiences (e.g., field trips, experimenting). Most of our participants remembered a few positive and many negative experiences in science class. We saw clear connections between these experiences and our participants’ self-positioning in relation to science and science learning. These experiences’ influence was sometimes felt over the years. Cohen et al. (Citation2021) described how college students remembered their positive experiences from elementary school and suggested that those experiences were the most influential on the students’ science capital.

This study highlights the importance of accumulating positive experiences and positive interactions with the science teacher in elementary school, to create positive memories in the context of science (Edy et al., Citation2019).

The science teacher: A broad impact on self-positioning towards science

Wood (Citation2019) identified two important components of positive teacher–student relationships – students perceive the teacher as being warm and caring, and the teacher recognises and celebrates the students’ competence within current learning activities – and two factors that predict negative teacher–student relationships – ignoring students when they are trying to participate and demonstrate their ability or knowledge, and perceived unfairness.

A single science teacher taught all the students in the second year of this study, and her negative impact was felt immediately and strongly on all the participants’ positions in relation to science. However, an awareness of what was going on, a critical view of the way science was being taught, by their science teacher, and a willingness to reconsider their positions in relation to science, appeared in most of the students only once this teacher was replaced. This can be seen in , in the row ‘Science teachers and school science’. The students seemed to realize that science learning in school could be a positive experience only once they had a positive learning experience with which they could compare and contrast their prior negative experiences (Kuhn, Citation1991; Pithers & Soden, Citation2000). This ability appeared at a late stage of the study, after the participants had experienced different teachers.

It was also apparent that as students matured, their relations with the science teacher received less significance in their eyes and less overall weight in their learning experience (Wood, Citation2019), playing a smaller role in their self-positioning towards science and science learning. Therefore, we recommend that science teachers who teach young children in elementary schools pay great attention to their relations with the students, to project warmth and caring, perhaps even more than what they are teaching (Tan & Barton, Citation2008), since when the students’ emotional experience with the teacher was bad, few could remember what they had been taught.

Conclusion

It should be recognised that adolescents’ self-positioning in relation to science can know ups and downs. Science teachers need to be aware of this and be patient when students aren’t fully attuned to what the teacher hoped to achieve. Emphasis should be placed on positive science-learning experiences. It is the emotional impact of these experiences, rather than the ideas learned during these experiences, that students remember and carry with them, and that appears to play a large role in students’ self-positioning in relation to science and science learning. Emphasis should also be placed on the science teacher developing warm personal relations with the students. Students want to be ‘seen’ by their teachers; they want to feel that they are personally important to their teachers. This appears to be especially important in elementary school. Finally, opportunities should be provided, and students should be encouraged to participate in after-school science programs as these can help make students more tolerant of unsatisfying experiences in school science and develop a longer-lasting interest in science.

Limitations

This longitudinal study aimed to convey the self-positioning of young adolescents in relation to science, between grades 4 to7, and to identify motifs which were common to these participants’ self-position. However, we followed only nine students. Hence the ability to generalise is limited. We did not use all the data we gathered; in some of the sessions, the children, and often the parents as well, opened their hearts in complete trust. Several personal and intimate moments, which were very relevant to this study, were kept discreet and were not included in this manuscript.

Ethics statement

This work was approved by the IRB Committee and by the Ministry of Education.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the children and their families that opened their homes and hearts to us and allowed us to get to know and accompany them over a long and complex period.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainley, M., & Ainley, J. (2011). A cultural perspective on the structure of student interest in science. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 51–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.518640

- Archer, L., Dawson, E., DeWitt, J., Seakins, A., & Wong, B. (2015). “Science capital”: A conceptual, methodological, and empirical argument for extending bourdieusian notions of capital beyond the arts. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(7), 922–948. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21227

- Archer, L., DeWitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., & Wong, B. (2010). “Doing” science versus “being” a scientist: Examining 10/11-year-old schoolchildren’s constructions of science through the lens of identity. Science Education, 94(4), 617–639. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20399

- Arnold, J., & Clarke, D. J. (2014). What is ‘agency’? Perspectives in science education research. International Journal of Science Education, 36(5), 735–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2013.825066

- Aschbacher, P. R., Li, E., & Roth, E. J. (2010). Is science me? High school students’ identities, participation and aspirations in science, engineering, and medicine. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(5), 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20353

- Avargil, S., Kohen, Z., & Dori, Y. J. (2020). Trends and perceptions of choosing chemistry as a major and a career. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 21(2), 668–684.

- Banks, J., Au, K., Ball, A. F., Bell, P., Gordon, E., Gutierrez, K., Brice-Heath, S., Lee, C. D., Mahiri, J., Nasir, N., Valdes, G., & Zhou, M. (2007). Learning in and out of school in diverse environments: Life-long, life-wide, life-deep.. The LIFE Center (University of Washington, Stanford University and SRI) & the Center for Multicultural Education, University of Washington.

- Barmby, P., Kind, P. M., & Jones, K. (2008). Examining changing attitudes in secondary school science. International Journal of Science Education, 30(8), 1075–1093. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701344966

- Barton, A. C. (2001). Science education in urban settings: Seeking new ways of praxis through critical ethnography. Journal of Research in Science Teaching: The Official Journal of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, 38(8), 899–917. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.1038

- Basu, S. J., & Barton, A. C. (2007). Developing a sustained interest in science among urban minority youth. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(3), 466–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20143

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

- Bell, P., Bricker, L., Reeve, S., Zimmerman, H. T., & Tzou, C. (2013). Discovering and supporting successful learning pathways of youth in and out of school: Accounting for the development of everyday expertise across settings. In LOST Opportunities: Learning in Out-of-School Time (pp. 119–140). Springer.

- Bell, P., Tzou, C., Bricker, L., & Baines, A. D. (2012). Learning in diversities of structures of social practice: Accounting for how, why and where people learn science. Human Development, 55(5–6), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1159/000345315

- Blakemore, S.-J. (2008). The social brain in adolescence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(4), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2353

- Blakemore, S.-J. (2012, Mar). Development of the social brain in adolescence. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 105(3), 111–116. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.2011.110221

- Bricker, L. A., & Bell, P. (2014). "What comes to mind when you think of science? The perfumery!”: Documenting science-related cultural learning pathways across contexts and timescales. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 51(3), 260–285.

- Burke, C.-A. (2020). Informal science educators and children in a low-income community describe how children relate to out-of-school science education. International Journal of Science Education, 42(10), 1673–1696.

- Carlone, H. B., & Johnson, A. (2007). Understanding the science experiences of successful women of color: Science identity as an analytic lens. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(8), 1187–1218. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20237

- Carskadon, M. A., Acebo, C., & Jenni, O. G. (2004). Regulation of adolescent sleep: Implications for behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1308.032

- Caspi, A., Gorsky, P., Nitzani-Hendel, R., Zacharia, Z. C., Rosenfeld, S., Berman, S., & Shildhouse, B. (2020). Children’s perceptions of the factors that led to their enrolment in advanced, middle-school science programmes. International Journal of Science Education, 42(11), 1915–1939. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1802083

- Cohen, S. M., Hazari, Z., Mahadeo, J., Sonnert, G., & Sadler, P. M. (2021). Examining the effect of early STEM experiences as a form of STEM capital and identity capital on STEM identity: A gender study. Science Education, 105(6), 1126–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21670

- Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (1990). Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational Researcher, 19(5), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X019005002

- Cros, D., Maurin, M., Amouroux, R., Chastrette∗, M., Leber, J., & Fayol, M. (1986). Conceptions of first-year university students of the constituents of matter and the notions of acids and bases. European Journal of Science Education, 8(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140528860080307

- Deci, E. L. (1992). The relation of interest to the motivation of behavior: A self-determination theory perspective. In K. A. Renninger, S. Hidi, & A. Krapp (Eds.), The role of interest in learning and development (pp. 43–70). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- DeWitt, J., & Archer, L. (2015). Who Aspires to a Science Career? A comparison of survey responses from primary and secondary school students. International Journal of Science Education, 37(13), 2170–2192. http://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1071899

- DeWitt, J., Osborne, J., Archer, L., Dillon, J., Willis, B., & Wong, B. (2013). Young children’s aspirations in science: The unequivocal, the uncertain and the unthinkable. International Journal of Science Education, 35(6), 1037–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2011.608197

- Dierks, P. O., Höffler, T. N., Blankenburg, J. S., Peters, H., & Parchmann, I. (2016). Interest in science: A RIASEC-based analysis of students’ interests. International Journal of Science Education, 38(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2016.1138337

- Dorfman, B. S., & Fortus, D. (2019). Students’ self-efficacy for science in different school systems. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 56(8), 1037–1059. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21542

- Ebner, N. C., Kamin, H., Diaz, V., Cohen, R. A., & MacDonald, K. (2014). Hormones as “difference makers” in cognitive and socioemotional aging processes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01595Edy

- Edy, H., Mohd, S., Halim, L., Rasul, M. S., Osman, K., Nurazidawati, M. (2019). Students’ interest towards STEM: a longitudinal study. Research in Science and Technological Education, 37(1), 71–89.

- El Takach, S., Yacoubian, H. A. (2020). Science teachers’ and their students’ perceptions of science and scientists. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 8(1), 65–75. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijemst.v8i1.806

- Erikson, E. H. (1994). Identity youth and crisis. WW Norton & Company.

- Farland-Smith, D. (2019). Developing young scientists: The importance of addressing stereotypes in early childhood education. In Early childhood education (pp. 1–12). IntechOpen.

- Feder, M. A., Shouse, A. W., Lewenstein, B., & Bell, P. (2009). Learning science in informal environments: People, places, and pursuits. National Academies Press.

- Fischer, H. E., Girwidz, R., & Treagust, D. F. (2022). Topics of physics education and connections to other sciences. In Physics Education (pp. 1–23). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Foeken, L. (2018). Exploring the gender gap in science education: The effects of parental support and parental role modeling on students' academic selfefficacy and intrinsic motivation. Master's Thesis, University of Twente.

- Franse, R. K., Van Schijndel, T. J., & Raijmakers, M. E. (2020). Parental pre-knowledge enhances guidance during inquiry-based family learning in a museum context: An individual differences perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1047. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01047

- Gilmartin, S. K., Li, E., & Aschbacher, P. (2006). The relationship between interest in physical science/engineering, science class experiences, and family contexts: Variations by gender and race/ethnicity among secondary students. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 12(2-3), 179–207. https://doi.org/10.1615/JWomenMinorScienEng.v12.i2-3.50

- Hahn, C., Cowell, J. M., Wiprzycka, U. J., Goldstein, D., Ralph, M., Hasher, L., & Zelazo, P. D. (2012). Circadian rhythms in executive function during the transition to adolescence: The effect of synchrony between chronotype and time of day. Developmental Science, 15(3), 408–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01137.x

- Harré, R., & Van Langenhove, L. (1991). Varieties of positioning. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 21(4), 393–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1991.tb00203.x

- Hazari, Z., Cass, C., & Beattie, C. (2015). Obscuring power structures in the physics classroom: Linking teacher positioning, student engagement, and physics identity development. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(6), 735–762.

- Hazari, Z., Sonnert, G., Sadler, P. M., & Shanahan, M.-C. (2010). Connecting high school physics experiences, outcome expectations, physics identity, and physics career choice: A gender study. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 47(8), 978–1003. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20363

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4

- Hoferichter, F., & Raufelder, D. (2019). Mothers and fathers—Who matters for STEM performance? Gender-specific associations between STEM performance, parental pressure, and support during adolescence. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 4, p. 14), SA. Frontiers Media. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00014

- Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, Israel. (2016). Publication #1722. https://www.cbs.gov.il/he/publications/pages/2018/%D7%94%D7%A8%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%99%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%94%D7%9E%D7%A7%D7%95%D7%9E%D7%99%D7%95%D7%AA-%D7%91%D7%99%D7%A9%D7%A8%D7%90%D7%9C-2016.aspx

- Jenkins, E. (2019). Science for all: The struggle to establish school science in England. UCL IOE Press. UCL Institute of Education, University of London, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL.

- Kelly, G. M. (2019). Social networks and science identity: Does peer commitment matter?. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska.

- Kewalramani, S., Phillipson, S., & Belford, N. (2020). How parents engaged and inspired their young children to learn science in the later years: A story of 11 immigrant parents in Australia. Research in Science Education, 52(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-020-09919-9

- King, D., Ritchie, S., Sandhu, M., & Henderson, S. (2015). Emotionally intense science activities. International Journal of Science Education, 37(12), 1886–1914. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1055850

- Krapp, A., & Prenzel, M. (2011). Research on interest in science: Theories, methods, and findings. International Journal of Science Education, 33(1), 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2010.518645

- Kuhn, D. (1991). The skills of argument. Cambridge University Press.

- Makarova, E., Aeschlimann, B., & Herzog, W. (2019). The gender gap in STEM fields: The impact of the gender stereotype of math and science on secondary students’ career aspirations. Frontiers in Education, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2019.00060

- María, J. H.-S., & José, M. M.-R. (2020). Interest in STEM disciplines and teaching methodologies: Perception of secondary school students and preservice teachers. Educar, 56(2), 369–386. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/educar.1065

- Massey, E. K., Gebhardt, W. A., & Garnefski, N. (2008). Adolescent goal content and pursuit: A review of the literature from the past 16 years. Developmental Review, 28(4), 421–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2008.03.002

- Mayring, P. (2016). Einführung in die qualitative sozialforschung. Beltz.

- OECD. (2000). Science, Technology and Innovation in the New Economy. Policy Brief. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/science/sci-tech/1918259.pdf

- Okafor, B. I., & Okpli, J. N. (2020). Predicting secondary school students’ interest in biology using emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and self-esteem. International Journal of Innovative Research and Advanced Studies, 7(3).

- Papadimitriou, M. (2004). In their Own words: What girls Say about their science education experiences. Science Education Review, 3(4), p112.1–112.16.

- Pattison, S. A., & Dierking, L. D. (2019). Early childhood science interest development: Variation in interest patterns and parent-child interactions among lowincome families. Science Education, 103(2), 362–388.

- Pithers, R. T., & Soden, R. (2000). Critical thinking in education: A review. Educational Research, 42(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/001318800440579

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 8(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080103

- Protacio, M. S. (2019). How positioning affects English learners’ social interactions around reading. Theory Into Practice, 58(3), 217–225.

- Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72(4), 1135–1150. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00338

- Scholes, L., & Stahl, G. (2020). ‘I’m good at science but I don’t want to be a scientist’: Australian primary school student stereotypes of science and scientists. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 26(9), 927–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2020.1751316

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2006). Competence and control beliefs: Distinguishing the means and ends. In P. A. Alexander, & P. H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 349–368). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Shin, D. D., Lee, M., Ha, J. E., Park, J. H., Ahn, H. S., Son, E., ... Bong, M. (2019). Science for all: Boosting the science motivation of elementary school students with utility value intervention. Learning and Instruction. Learning and Instruction, 60, 104–116.

- Starr, C. R. (2018, Dec). “I’m not a science nerd!” STEM stereotypes, identity, and motivation among undergraduate women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 42(4), 489–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684318793848

- Swidler, S. A. (2000). Contextual conflicts in educators? Personal experience narratives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 13(5), 553–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390050156468

- Tan, E., & Barton, A. C. (2008). From peripheral to central, the story of melanie's metamorphosis in an urban middle school science class. Science Education, 92(4), 567–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20253

- Taylor, D. C. (2019). Out of school time (OST) STEM activities impact on middle school students’ STEM persistence: A convergent mixed methods study (Doctoral dissertation). https://hdl.handle.net/2346/85001

- Thomasian, J. (2011). Building a science, technology, engineering, and math education agenda: An update of state actions. NGA Center for Best Practices.

- Touitou, I. (2016). Using environmental factors to predict changes to students' motivation to learn science in and out of schools that serve low socioeconomic populations. Weizmann Institute of Science.

- Varelas, M., Kane, J. M., & Wylie, C. D. (2012). Young black children and science: Chronotopes of narratives around their science journals. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(5), 568–596. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21013

- Varelas, M., Tucker-Raymond, E., & Richards, K. (2015). A structure-agency perspective on young children's engagement in school science: Carlos's performance and narrative. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(4), 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21211

- Vedder-Weiss, D., & Fortus, D. (2011). Adolescents’ declining motivation to learn science: Inevitable or Not? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(2), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20398

- Vedder-Weiss, D., & Fortus, D. (2013). School, teacher, peers, and parents’ goals emphases and adolescents’ motivation to learn science in and out of school. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(8), 952–988. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21103

- Wahlstrom, K. L. (2002). Accommodating the sleep patterns of adolescents within current educational structures: An uncharted path. In M. A. Carskadon (Ed.), Adolescent sleep patterns: Biological, social, and psychological influences (pp. 172–197). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511499999.014

- Wang, J., Yang, M., Lv, B., Zhang, F., Zheng, Y., & Sun, Y. (2020). Influencing factors of 10th grade students’ science career expectations: A structural equation model. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 19(4), 675–686. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/20.19.675

- Wenner, J. A., & Settlage, J. (2015). School leader enactments of the structure/agency dialectic via buffering. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 52(4), 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21212

- Wolfson, A. R., & Carskadon, M. A. (2003). Understanding adolescent’s sleep patterns and school performance: A critical appraisal. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 7(6), 491–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1087-0792(03)90003-7

- Wood, R. (2019). Students’ motivation to engage with science learning activities through the lens of self-determination theory: Results from a single-case school-based study. Eurasia journal of mathematics. Science & Technology Education, 15(7), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/106110

- Yerrick, R., Schiller, J., & Reisfeld, J. (2011). Who are you callin’ expert?”: Using student narratives to redefine expertise and advocacy lower track science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(1), 13–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.20388

- Young, J. L., Young, J. R., & Ford, D. Y. (2019). Culturally relevant STEM Out-of-school time: A rationale to support gifted girls of color. Roeper Review, 41(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2018.1553215

- Zimmerman, H. T. (2012, May). Participating in science at home: Recognition work and learning in biology. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(5), 597–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21014

Appendices

Appendix A

Teachers

There were three science teachers at the ES at the start of the study. Sharon had 5 years’ teaching experience, all at this ES. Sharon studied elementary education at a teachers’ college with science as her content emphasis. Natalie taught for 17 years in two different elementary schools. For the first 5 years, at her former ES, she taught literature, then because of scarcity of science teachers, the principal of that school suggested that she change her specialisation to science. She took the required courses, and since then she teaches science, meanwhile switching schools. She was the science coordinator at the ES. Rose joined the teaching staff two years before the study began, and served as a substitute teacher while completing a science teaching certificate.

There were two seventh-grade science teachers at the JHS. Charlotte had a MSc in science and 15 years’ teaching experience. Megan was a new teacher with a bachelor’s degree in marine science and was completing her studies for a teaching certificate in parallel with her first year as a teacher.

Appendix B – after-school programs

We visited three times in each year of the study, the relevant non-school related after-school science programs in which the focus students participated. The non-science-oriented after-school programs were visited by us only once during the study. During these visits, we interviewed the instructors and observed the focus student(s). The names of the programs are anonymous.

Science for everyone

The purpose of the program is to provide opportunities for adolescents to learn science experientially. The program took place in the local community center after the end of the school day. There were about 20 participants. All students who were interested in participating were required to take an acceptance test at the end of fourth grade (the actual chief aim of the test was to increase the program’s prestige and less to rate students). During the year, the students met for 30 ninety-minute sessions with two instructors from the program. Twenty-five of the meetings were held as learning sessions that were divided into 25% lecturing and 75% participant activity. In the last five sessions, participants built an apparatus based on the year’s curriculum. Most of the program’s instructors had a BSc in science. Three students from the focus groups participated in this entire program.

Excellence in mathematics

Its purpose is to enrich students mathematically. The students are exposed to content that is not included in the regular curriculum and are preparing for the program for talented youth in mathematics. The program took place at the local community center after the end of the school day. Each student who was interested in the program took an acceptance test at the end of fifth grade (the aim of the test was to rate the students according to their ability in math). During the year, the participants met for 30 ninety-minute sessions with an instructor, who was a JHS mathematics teacher (not the JHS which participated in this study). All activities were drawn from a workbook given to the participants. Two students from the focus groups participated in this program. One retired in the middle and the other finished the program. The children who participate in this program are often labelled as smart/talented in school by their peers and sometimes by the teachers. Overlapping can be seen of these children with scientific programs offered at the school.

Children of the forest

The program aims to learn the life skills of earth cultures as a tool for connecting man to himself and others, his role in the ecosystem, and creation as a whole. There are no planned activities for the meeting. The children are asked to find the occupations for the meeting's duration and explore nature from a personal interest. This is a non-science-oriented program that took place in a forest near the school. However, this program has the possibility to engage in scientific content, whether under the guidance of the instructors or as a result of interest coming from the children. The meetings were held every week for the whole year, each meeting lasting about 4 hours. In addition, there were weekend meetings, including all of the family. During these meetings, the students experienced various activities in the context of nature in the forest. Two instructors guided the group. One student from the focus groups participated in this activity.

The Israeli scouts

Its goal is to develop young people physically and spiritually so that youth can take a more helpful place in society. This goal is achieved through non-formal education with an emphasis on practical activities outdoors in nature. Meetings were held twice a week for the whole year, each meeting lasting about an hour and a half. In addition, there were field trips and camps throughout the year. During these meetings, the students play various games and sometimes participated in activities on topics like values of the state, religion and knowledge of the country. The group was guided by two 10th-grade instructors who were also members of the Scouts. Five students from the focus groups participated in this activity. This program has a broad social impact on children. To get a complete picture of the children's effects, it was important for us to visit this program.

Science excellence

The purpose of the program is to enable students who excel in science, according to a sorting test, to delve deeper into science studies in addition to classroom hours. The program was held in the junior high school. At the beginning of seventh grade, all the new students took a ranking test to check their suitability for the program (the aim of the test was to rate the students’ ability). About 50 students were admitted and were divided into two groups, each which met once a week at the end of the school day, as extra school hours. The lessons were taught by the JHS’s science teachers and included visits to the nearest university. Students in the program were required to maintain high grades in their ‘regular’ science classes. If they did not behave properly or if their grades dropped, they were expelled from the program. There were no grades or tests in the program. In each lesson, the students were divided into groups and conducted an experiment. The lessons were accompanied by a dedicated textbook which guided the students and in which they answered questions. Students who completed the program in seventh grade and succeeded on all the assignments could choose to continue in the program in 8th grade as well. In eighth grade, this program replaced their regular science classes, so the students were not required to study ‘regular’ science with the other students. Two students from the focus groups participated in this entire program.

Appendix C – summaries of the stories

Anna

Anna is a smart and pleasant girl. Throughout our acquaintance, I have witnessed Anna grow and mature in all aspects of life. At first, it was evident that Anna was searching for her path, with her friends and personal interests. The social difficulties in the fourth grade were a great challenge for Anna. When she managed to overcome them and create meaningful friendships, other aspects began to emerge and become meaningful as well. Anna's self- confidence improved, and her demeanor was noticeably more relaxed.

It seems that Anna knows very well what she would like to do when she grows up and what her interests are.

- ‘Me, personally, my goal in life, is to be an actress, I can explain myself very well I'm not shy and can explain myself in front of an audience’

Anna is aware of science and scientists and can talk about them, but the subject does not appeal to her.

- What do you think scientists do?

- ‘Look, there are all sorts, let's say if I was a scientist then I think I would've liked to work in the medicine field and stuff. I think that they test all kinds of things that can help us or test things in order to raise awareness, what is good and what is bad, meaning what I shouldn't eat and what I should.’

- When they wake up in the morning and go to work, what do they do? What does a scientist's day look like?

- ‘Okay, I think that if I for example want to check what is an atmosphere, I wake up in the morning and then I come to the lab, first I take a sample that I prepared yesterday, I test it and look at the findings, is that what they're called?’

She enjoys reading about science, long novels that are related to the field, and this satisfies her. She found her passion in dancing and acting.

Anna's attitude towards science has changed through the years. In the beginning, in the fourth and fifth grades, Anna disliked science and talked about the lessons only in terms of grades and achievements.

- What do you learn in science class?

- ‘I got 77 points on my test’

In the fifth grade, Anna started attending an extracurricular science activity. It was apparent that the activity was not making any substantial difference in Anna's attitude towards science. She has said over the years that she enjoys conducting experiments, but the science field bores her.

- Would you choose to go to Davidson again?

- ‘I don't know’

- This year, if it was possible would you go?

- ‘It is possible’

- And you don't want to?

- ‘No’

The most significant change in relation to science began in the sixth grade when a new teacher came to teach the subject. Anna started talking about science classes with enthusiasm and sharing her experience in class with almost no mention of her grades.

- -Tell me about science this year [sixth grade]

- ‘well actually this year science is much ‘cooler’, because the teacher is like, she knows … like she knows how to keep us interested’

At the same time, Anna started to listen to the conversations her father has at home with her brother and her about science. A whole new world had opened up to her. Anna started to show an interest in the philosophy of science. However, her passion remained and is currently dancing and acting.

- ‘I'm interested in philosophy’

- Okay, what is philosophy?

‘It's my dad, he's studying it, he is doing a master's degree, I learnt a lot about it, I even read a book about it. Um speaking about science, only about a book about philosophy and that's part of science in some way’

- And we're looking for an agent for me’

- For the acting?

- ‘Yes, so that I will be able to make some progress in the industry.’

- It sounds like the performing arts and acting are your passion … What you enjoy doing

- ‘Yes, totally’

- Is that also what you would like to be doing in the future?

- ‘Yes, to be an actress’

- In the theatre in movies where?

- ‘In movies’

Anna is aware of the teacher's demeaner and treatment in class and can describe how important is to her. In relation to science, Anna's teacher in the fourth and fifth grades (the same teacher) was fixated and taught only from the workbook using a rigid method that caused Anna to feel distant and detached from the science field.

- ‘Natalie just didn't care about us, she didn't even try to teach us in an interesting way, she didn't try, look last year the entire class got grades that were 80 and below in all of the tests, this year, all the grades were 70 and above.’

The teacher's impact was so strong that it was impossible for Anna to disconnect this experience with science from her other experiences, such as her extracurricular science activity in the fifth grade or her conversations with her father who talked about science and scientists at home.