ABSTRACT

This study examines how multilingual students (11-12 years) negotiate meaning in writing, drawing, and dialogues in science. Students use emotions, reflections, and experiences from areas other than school when given the opportunity to solve an open-ended task in science. Data consists of texts from three multilingual students and excerpts from co-generative dialogues collected over five months.

Expressions of meaning in the students’ drawing, writing, and oral explanations were analysed using a social semiotic framework. The findings illustrate how emotions and everyday experiences play a significant role in the students’ work to create meaning about science knowledge. Furthermore, the findings indicate that students engage through experiences from learning arenas other than school and that those have the potential to create curiosity and negotiation of identity, language, and subject knowledge.

The study reflects upon how the aspects of social semiotic theory, identity, agency, and investment are intertwined with subject-specific knowledge when students negotiate meaning. One implication highlighted is the need for consciousness related to students’ different use of semiotic resources, and to encouraging multilingual students to use their semiotic resources. This implies a potential for students to develop science knowledge and teachers to identify their meaning-making process.

Introduction

Students enter the classroom with a wide range of resources established through different experiences. These resources are ubiquitous in meaning-making as they constitute the basis of learning processes (Hodge & Kress, Citation1988; Siry, Citation2020). Constructing new knowledge in science is associated with transformations of former experiences (Kress, Citation2020). The various experiences children have with languages, cultures, and nature, combined with different interests, talents and emotions build a basis for their learning processes (Kress, Citation2020). Thus, how to create meaning about science varies among students learning together in the same classrooms.

Diversity in connection with students’ linguistic and cultural profiles is growing in European contexts, resulting in many students being positioned to learn science through languages they are working to master (European Commission, Citation2017). Norwegian teachers experience challenges related to diversity in science classrooms (Danbolt, Citation2020). In Norway, primary and lower secondary education is founded on the principle of a unified school which aims at providing equal education for all, based on one national curriculum (The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training, Citation2023). However, multilingual students speaking another language at home than the language of instruction in school stand out as one group with a significant reduction in science results at the TIMSS survey in 2019 compared to 2015 (Lehre & Nilsen, Citation2021). Directing the attention towards how the students can incorporate various resources in meaning-making in science can influence this development.

Our study explores how the students in a diverse classroom can be encouraged to utilise various experiences from languages, cultures and nature combined with interest, creativity, and emotions when they learn about sound and ecology. The aim is to contribute to a discussion about how to engage students in learning processes by encouraging them to create meaning in science. Based on social semiotics, meaning-making is associated with students ‘remaking information’, and ‘reshaping meaning’ (Jewitt et al., Citation2001, p. 6). We see meaning-making as a consequence of active choices, which in science involves students choosing what resources to use when they e.g. solve problems, express knowledge or engage in a dialogue. In a science context, making active choices implies that students are allowed to use various languages, experiences, interests, and curiosity in science activities. Learning based on such approaches is potentially transformative, involving reshaped meaning to be integrated into the students. Also, it challenges all the students to take an active part and be able to experience mastery (Siry & Gorges, Citation2020). In this study, we analyse and discuss parts of the meaning-making process of three multilingual students in a Norwegian school class (10-11 years old) creating ‘identity texts’ and taking part in a following dialogue.

Identity texts are based on the principle that students construct visual products by using resources of their choice to express a meaningful message (Cummins, Citation2019; Cummins & Early, Citation2011). The texts can be tools to help students express knowledge and skills. Also, they can provide teachers with knowledge about how multilingual students create meaning in science. By using a social semiotic framework, this study explores the potential of identity texts by revealing situations that, in many cases, are inconspicuous. Identity texts allow students to link their experiences and associations to the science content. We explore the potential of including identity texts in a science classroom by investigating the research questions:

How do multilingual students use resources and express identity as part of meaning-making processes in identity texts about a science topic?

How can scientific identity texts provide teachers with information about multilingual students’ transformation of subject knowledge?

Theory

A wide range of resources is ubiquitous as students work with meaning-making in the science classroom. Subject knowledge, everyday experiences, values, and attitudes form the resources students utilise (Jewitt et al., Citation2001; Kress, Citation2010). To multilingual students, various language experiences are among the resources that can facilitate meaning-making (Cummins, Citation2014; Siry & Gorges, Citation2020). Also, emotions (Siry & Brendel, Citation2016), interests, social interactions and sensory experiences from everyday life play an essential role in the students’ base in which they create scientific meaning (Hodge & Kress, Citation1988; Kress, Citation2020).

Social semiotics in a science context

Social semiotics connects meaning to social action and implies that meaning arises from social interactions in specific contexts (Kress, Citation2020). Learning can be seen as a process in which learners actively transform information communicated and shared in a classroom (Jewitt et al., Citation2001). Halliday (Citation2006) explains learning from such an understanding as a dynamic sign creation process. In a classroom, this involves students re-shaping signs used in dialogues and communication through various resources. What resources the students chose to use is a central part of learning processes in social semiotics:

Difference of personal «interest» of the participants, leading to difference in focus, leading to difference in selecting aspects from a message; based on differences in the ‘deeper’ perspectives from which each of us selects elements to newly constitute the message. (Kress, Citation2020, p. 26)

Social semiotics suggests how meaning is conveyed in a framework based on forms of mode. Speech, written text, images, concrete models, gestures, and facial expressions are among these (Kress, Citation2010), as well as colours and various symbols (Kress & Leeuwen, Citation2021; Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2002). Within social semiotics, meaning is expressed within three dimensions. These originate from Functional Linguistics (Halliday, Citation2014). Among other things, Halliday points out that all communication takes place within two dimensions; the ideational, which is reflective, and the interpersonal, which is associated with an activity. These are perceived as two-purpose meta-functions, one of which is about understanding one's surroundings, and the other is about acting in connection to one's surroundings. In addition, there is a third meta-function, the textual one, described as making the other two relevant (Maagerø, Citation1998).

Multilingual students and the academic language

The multilingual students in this study have immigrant backgrounds and learn Norwegian as their second language (L2) in parallel with learning natural science. Children who move to a new country usually learn the everyday language of the new country relatively quickly, while skills in technical language are built up over time. Cummins (Citation2014) shows that immigrant students who learn the school language as a second language may spend five to seven years learning the academic language to the same level as their peers learning in their first language (L1). These challenges may be inconspicuous in the science classroom and can easily be overlooked.

Language is the tool students use to demonstrate knowledge and to participate in discussions and activities aimed at building knowledge (Lemke, Citation2001). Also, different experiences with culture and text can provide different prerequisites for creating meaning in science. This might create differences that contribute to students perceiving themselves as less knowledgeable than their peers. One unfortunate consequence of this is that students can choose silence and be perceived as passive (Duff, Citation2002).

Identity texts in a science context

Identity texts are products students make in creative work in situations orchestrated by the teacher to allow the students to involve familiar experiences and personal interests when solving written tasks. They provide an opportunity to affirm students' identities in the situated school context, which is of major importance as affirmation of identities is directly related to academic achievement (Cummins, Citation2014). These texts can be written, spoken, signed, visual, musical, dramatic, or combinations in multimodal form, and students invest their identities as they create them (Cummins & Early, Citation2011, s. 3). Often, they consist of written text in different languages multilingual students know, but the potential of identity texts has been highlighted for students also learning in their L1 (Cummins, Citation2021, p. 313). What characterises identity texts, are personal expressions of ideas, thoughts, emotions, and experiences, rather than academically correct answers. Thus, the limitations of these texts might be a lack of academic content. However, the purpose of identity texts is to facilitate the student's experience of relevance of the science topic, to provide an opportunity for the students to actively participate, affirm the student's identity and for the teacher to get information about the student's meaning-making process.

As one of several tasks included in inquiry-based teaching, identity texts have the potential to help students bridge between everyday experiences and science topics. This makes identity texts relevant in most classrooms. However, to multilingual students these texts can be particularly important, as they communicate a message from the teacher to the students, saying that their languages and experiences are valuable. This is of major importance for multilingual students, as languages and backgrounds are associated with stigmatisation, shame and active choices about not to participate (Duff, Citation2002). Thus, identity texts aim to provide students with an opportunity to actively participate and engage in learning processes (Cummins, Citation2014).

In prior research, the emphasis on identity texts is often the use of various languages (Rajendram et al., Citation2022; Zapata & Ribota, Citation2021). However, studies also show that identity texts have potential in contexts where the main emphasis has been placed on content and expression without the attention pointed towards different languages. For example, the study of Zaidi and El Chaar (Citation2022) shows identity texts consisting of drawings, image collages and combinations of text and drawing when adult university students expressed their experiences related to multiculturalism. These texts provided insight into situations that, in many cases, would have been difficult to discover. In another study, math identity texts were examined in a classroom with 2nd to 5th-grade L2 students (Cummins et al., Citation2015). The students incorporated lived experiences as they were creating number-sense problems and timelines in photo stories.

In a science context, identity texts have a potential to allow students to experience academic mastery and recognition. This implies that identity texts in disciplinary teaching are student-oriented, allowing free choices on what to express. This can include the use of various languages, as well as an opportunity to connect outdoor, cultural, social, and emotional experiences to a science topic. Identity texts can, combined with dialogues, be rich tools to inform learning (Book, Citation2022). Thou, identity texts do not stand alone when students develop meaning in science. They are one of several tasks that students are challenged with in inquiry-based learning, potentially facilitating the students' bridging to the science discourse.

Interpreting identity texts with social semiotics

A social semiotic approach can illuminate essential aspects of student work that communicate parts of meaning-making processes (Knain et al., Citation2021; Wanselin et al., Citation2021). Such an approach aims to emphasise opportunities and strengths in student work. It also reveals the connection between scientific meaning-making and students’ interests, intentions, identities, everyday experiences, and social relationships. Thus, the social semiotic framework can frame various knowledge and unravel the pupils’ resources and starting points for further learning.

Method

The study is part of a research project investigating multilingual students' participation in science with an ethnographic-inspired approach. The data material includes identity texts, observations, and sound records from dialogues, collected over five months. The collection of the data material was incorporated as part of ordinary science teaching, and the scientific topics were related to the school class’ exploratory work with sound and plants.

Data collection

On each implementation, the students in the whole class created scientific identity texts related to the academic content. Using identity texts in a science context implies that the student's identity related to science is examined. The instructions did not require students to describe academic aspects in words since a free form of expression could facilitate access to the subject matter for students with varied language experiences. The students spent about 15 min on this part of the task.

Immediately after the whole-class activity, focus students took part in dialogues together with a peer and a researcher (one of the authors). The structure of the dialogues was inspired by co-generative dialogues (Tobin & Roth, Citation2006). Both L1 and L2 students took part. Excerpts from dialogues involving multilingual students participating with different peers were transcribed (31 transcripts in total). Each dialogue lasted between 10 and 19 min. Five identity texts and corresponding excerpts from the dialogues with three multilingual students are analysed. They are purposefully chosen because the students' participation reveals different situations related to multilingualism in science.

The focus students

The multilingual students participating in the study are called Lin, Anna, and Leila. Lin's family background is from Myanmar (Burma), Anna's is Kurdish, and Leila arrived from Syria with her family about two years before the data collection. Lin has grown up in Norway, and according to herself she speaks Norwegian with her siblings and friends, and she answers in Norwegian when her parents talk to her in their L1. Also, Anna mainly speaks Norwegian, but she explains how she practices her Kurdish every year before she visits her grandparents in Turkey. Leila speaks Arabic with her family and Norwegian with her friends.

Analysis of student texts

The analysis is inspired by former studies using social semiotic frameworks in a science teaching context (Knain et al., Citation2021; Wanselin et al., Citation2021). Texts and excerpts are analysed together, by identifying how meaning is realised through the textual, ideational, and interpersonal metafunctions establishing the basis for SFL (Systemic Functional Linguistics) (Halliday, Citation2006) and social semiotics (Hodge & Kress, Citation1988). Our tool for analysis () is inspired by the framework developed by Wanselin et al. (Citation2021, p. 896). Our data includes both written and oral expressions, and the first part of our analysis involved an adaption of the framework. Our adaptions include aspects important to multilingual students, for example, multimodal approaches and agency, intertwined with the social semiotic framework developed by Wanselin et al. (Citation2021). Prior research emphasises how various modalities (Kress, Citation2010), non-linguistic modes (Williams & Tang, Citation2020) and opportunities for active participation (Siry et al., Citation2016) play a particularly prominent role in multilingual students learning science. The second part of our analysis process was to identify the student's expressions of meaning within each of the categories defining the textual, the ideational and the interpersonal metafunction.

Table 1. The framework developed for the analysis of the data material in the study describes parameters for the identification of the three metafunctions in student texts.

The category defined as the textual metafunction revolves around the organisation of the content. This includes interpretations of the connection between the content expressed in different modes and the students’ choices of the utilisation of resources. The ideational metafunction points towards reflections and expression of the subject-specific content through processes, participants, and circumstances. The interpersonal metafunction aims to reveal relationships between drawn and written elements and oral participation. This part of the analysis focuses on redundancy, extension, elaboration, and contrast as the students express interests, choices, and science knowledge orally and in the texts (). Together, the analysis of the three metafunctions aims to emphasise how social semiotic theory can contribute to reveal a) the potential in tasks facilitating active participation by connections between identity and science, and b) provide the teacher with important information about the student's meaning-making process.

Results

Emotions and imagination as resources for learning science

The social semiotic analysis reveals that the students’ representations of the science topic are linked to imaginations, emotions, and sensory experiences. However, to what degree the students emphasise these aspects varies. For example, Lin is emotionally involved, and her negotiation about the topic is based on her feelings and sensory experiences (). Anna and Leila, on the other hand, are concerned with the topic ( and ). Their negotiation about Science relies upon everyday experiences but in connection to science-related experiences.

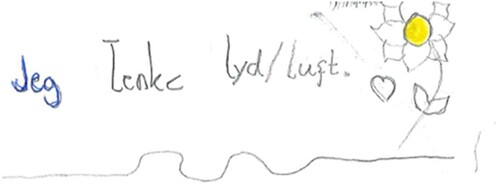

Figure 1. Lin´s identity text expressing the drawing of a flower and a line with wavelike shapes. She has written the words Jeg tenke lyd/luft (I think sound/air).

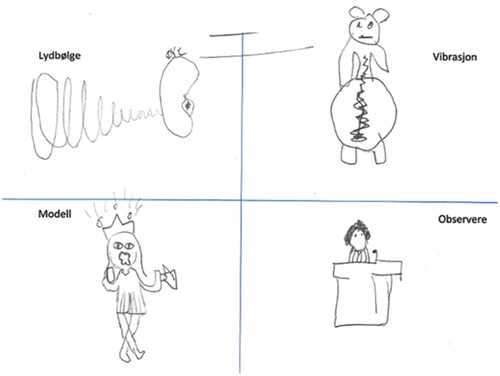

Figure 2. Lin´s identity text expressing reflections about the concepts soundwave (lydbølge), vibration (vibrasjon), model (modell) and observation (observere).

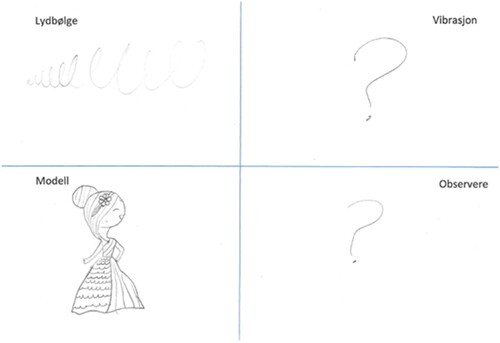

Figure 3. Leila´s identity texts expressing reflections about the concepts soundwave (lydbølge), vibration (vibrasjon), model (modell) and observation (observere).

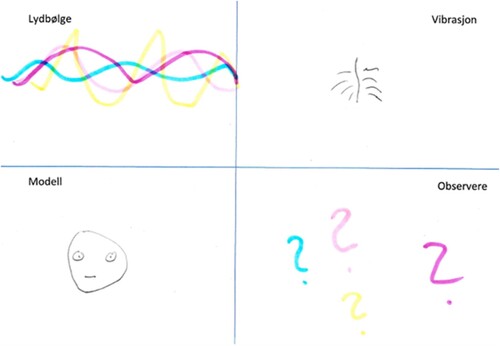

Figure 4. Anna´s identity text expressing reflections about soundwave (lydbølge), vibration (vibrasjon), model (modell) and observation (observere).

Figure 5. Lin´s identity text about plants consits of a drawing of a girl holding a flower. Two flowers are placed in front of the girl.

Lin's first drawing consists of one sentence (). The textual meaning is expressed by choosing a combination of writing and drawing. She has drawn a plant that is partially coloured, in addition to a grey line with two elevations that give associations to sound waves. In the written part, the student expresses that she thinks of sound and air together when she enters the two terms separated only by a ‘slash’. This may indicate that she perceives a connection between sound and air. The front part is short and consists of a statement. The drawing of the line with two elevations suggests that the student has depicted an expression of sound waves. If so, it connects with the content of her sentence. The plant has no direct connection with sound. The composition, shape, and placement of the flower contribute to foregrounding it. However, her statement in the interview after the text assignment indicates that she is not concerned about the academic aspect of the plant (excerpt 1).

The ideational meaning is expressed through emotional involvement. Lin uses the pronoun ‘I’ (Jeg), highlighted in blue (). This positions herself as a participant in the written text. In the drawing, the flower is a foregrounded participant, but the flower is irrelevant to her in the oral explanation. In the written text, Lin uses the verb ‘thinks’. Thinking is associated with mental processes related to senses and experiences (Maagerø, Citation1998), and Lin's associations with the topic seem to be strongly linked to her own experiences.

In the interpersonal analysis, the student expresses subject knowledge on the same topic (sound) through the sentence she has written and the illustration of the sound wave (the line below the sentence). The two forms of expression complement and exemplify each other, as the writing and illustration express more academic content combined than individually. Separately, they provide little insight into the student's experience of the science topic. The drawing of the plant expresses an entirely different part of science knowledge, and is, therefore, at odds with the other two modalities (written and oral). This dichotomy is reinforced through the pupil's oral explanation of the plant (excerpts 1). She does not seem interested in talking about sound and sound waves.

When Lin is challenged to explain why she chose to include a flower in her drawing, she avoids giving an adequate answer by taking a position as not interested. Her lack of interest can be a realistic experience, but it can also be a strategy to avoid a topic she perceives as difficult, giving her a feeling of not coping with it. In a school context, a lack of interest potentially is an indicator of a lack of experienced meaning and ability to connect abstract topics to emotions, curiosity, and interest from real-life experiences, rather than connected to interest and motivation.

Meaning expressed in drawing

Lin's second text consists of drawings expressing reflections about four scientific concepts (). Two of the concepts are related to content-specific knowledge about soundwaves (soundwave and vibration), and the two others are related to scientific practices (model and observe).

The textual part of the analysis reveals that Lin has chosen to express her reflections on the concepts through the mode of drawing. She does not use colours, and the combination of concrete elements (ear, bear, persons) and processes (listening, rumbling, singing, talking) is repeated in all four drawings. Lin's oral explanations reveal that she perceives the concepts as abstract and complicated, drawing on first-hand experiences.

Leila and Anna, however, seem to direct their attention towards the science topic ( and ). The textual part of the analysis of their texts also shows that they have chosen to draw. Leila draws sound waves as a spiral (), while Anna makes wave-like lines. Anna varies the colours on the lines with different amplitude, which gives associations to lines expressing different wavelengths (). Regarding the concept vibration, this is unknown to Leila. The dialogue reveals that she did not remember what this was, so she made the question mark (). Anna, on the other hand, has drawn one vertical line connected to several horizontal lines. Her oral explanation reveals that this illustrates a vibrating guitar string ().

Leila's reflections about the concept model are linked to a woman in a dress with a nice updo. Anna, on the other hand, has made a drawing of a head with eyes, a mouth, and a neutral facial expression. Leila is curious about the meaning of the concept model, especially when comparing her expression with Anna's. She takes the initiative to ask if a model is a person, and Anna replies that her drawing shows a human skull (excerpt 2). Observation is an unknown concept to both.

The ideational interpretation of Lin's expression about the four concepts shows that the drawings are linked to scientific processes (). Soundwaves are drawn with a spiral shape. They are linked to the ear, which becomes the ‘participant’ in the drawing. The ear is concrete and connected to powerful sensory experiences. The oral explanation complements the drawing when the student explains that the sound is coming from or to the ear (she is unsure at first, excerpt 3). She uses expressions such as ‘I don't know’ and ‘don't remember’ when talking about sound waves in this conversation. When it comes to vibration, Lin connects this to her own sensory experience, comparing the concept with the feeling of a rumbling stomach when she is hungry (it is likely that the girls are hungry at this moment since the interview ends with talking about the taste of pizza). However, Lin places a bear as the participant when she explains vibration as a bear with a rumbling stomach (excerpt 3).

Lin's oral explanation (excerpt 3) elaborates the drawing () as Lin informs that the participant in the drawing is a bear and the lines inside its stomach are associated with vibration. Both of her expressions revolved around comparable exposition, providing reflections at a macro level. When it comes to the concept model, she explains this: ‘Ehm, when it said model, I just thought it was a girl.’ She first associates observation with a person who talks a lot for a long time. During a brief discussion, she realises that she is doing the observation when she listens to and looks at a person who speaks.

The ideational analysis of Anna and Leila's texts ( and , and excerpt 3) suggests that concrete participants have no prominent role: Soundwaves are depicted without connection to the ear, people, or instruments. The soundwaves themselves occupy a prominent place. Vibration is portrayed as a guitar string. Hence, the guitar string has an important place in the presentation, while at the same time, it is the sound that is highlighted (foregrounded). The fashion model and skull model give associations to persons, but the conversation between the girls reveals that they emphasise model as a concept. Thus, the processes are highlighted; one can listen to a sound, vibration is something moving quickly from side to side, and a model visualises something. The girls express interest and curiosity in the natural science processes through the drawings and by taking the initiative in the dialogue.

Out-of-school experiences as resources for science meaning-making

Anna and Leila connect the science processes to experiences from outside of school. They are concerned with the experiences of having watched the episode about sound and hearing on the TV programme ‘The Magical Body’ (excerpt 4). The TV programme uses a lot of metaphors, and so do the girls.

The interpersonal analysis suggests that Lin's drawings () and oral explanations (excerpts 3 and 5) complement each other, suggesting redundancy to different degrees. Her explanations provide an extension of the drawings, as her oral information elaborates the meaning of the drawings alone.

The statements and drawings generally express experiences about the same concepts and phenomena. Nevertheless, they contradict each other to some extent. For example, the drawing of soundwaves () related to the ear might imply either that the sound is coming from the ear or that it is coming towards the ear. In the oral dialogue, this expression is strengthened as Lin seems uncertain about the sound's direction (excerpt 5). Her drawings are more expressive and dominant than her oral explanations. In the conversation with her partner, she participates when she is encouraged to speak up.

Leila and Anna largely elaborate on the drawing of three of the four concepts during the dialogue. Parts of their explanations indicate a reduced redundancy between the drawings of soundwaves and the oral explanations, as the girls refrain from talking about the soundwaves themselves. Instead, their attention is drawn towards what happens to the sound inside the body (excerpt 6). They chose to use resources from the TV show (Den magiske kroppen) rather than what was learned in class.

Lin's identity text from the beginning of an inquiry-based teaching programme about plants, illustrates her emotional approach to science work in classroom activities (). The textual analysis of Lin's drawing shows that she foregrounds a girl holding a flower. Her facial expression can be interpreted as calm and wellbeing, slightly smiling. Two flowers are placed in front of the girl as well. There are no colours in the drawing and no written text ().

The ideational interpretation shows that Lin places herself as the leading participant, slightly smiling as she is holding a flower. The oral explanation reveals that she connects this to familiar situations from home:

The drawing gives associations of positive emotions while being/when surrounded by plants on a nice summer day. Sensory experiences and emotions have a prominent place in the context of the subject matter.

The interpersonal analysis suggests Lin's experience of plants is emphasised to a greater extent (excerpt 7) than the knowledge about plants in the drawing (). The oral explanations both extend and elaborate this impression. There is a redundancy between the oral and drawn information, both expressing exposition at a macro-level.

Discussion

The identity texts analysed in the study reveal that the three multilingual students utilise different resources and negotiate identity in multiple ways as they create and explain the identity texts. To answer our first RQ, we start our discussion by highlighting aspects of the student’s language choices and everyday experiences. Then, we discuss the students’ positioning of self in connection to the subject-specific content. We answer our second RQ by discussing how identity texts and social semiotic theory can provide teachers with tools to facilitate meaning-making in teaching science.

Choice of language resources

The students strongly focus on science concepts, and there are similarities and differences between the students’ negotiation of the science content and their identities. One significant finding Anna, Leila and Lin have in common, is that although they are encouraged to express themselves in the way they want, none uses other languages than Norwegian (). Nor do they relate the science topic to experiences from other countries or cultures (excerpts 1-6). Utilising their repertoire of language experiences could have supported their negotiation about the topic (Garcia & Wei, Citation2013; Siry & Gorges, Citation2020). The students struggled with scientific concepts (e.g. excerpt 2 and 6), and it is noticeable that none used other languages to support their meaning-making. One reason might be that the students are unfamiliar with utilising a wide range of resources. However, linguistic, and social reasons might contribute to the students’ choices; Anna and Leila speak a different L1 (Kurdish and Arabic). None of the other students share their L1. If the girls chose to use their L1 in texts, their work would have low value in collaboration with peers. This situation indisputably forces the students to build academic identities connected to their L2 (Norwegian). Lin, on the other hand, is in another situation. Her best friend in the class shares her L1 (Burmese), and these girls could have utilised both languages as a resource. However, they oppose this. According to their teacher, they struggle to fit in among the other Norwegian girls in the class and are highly focused on constructing a ‘Norwegian identity.’ This might contribute to the choice of using their L1 in learning situations. On the other hand, we are also likely to believe that this scientific topic and its concepts are not known to the students on their respective L1.

The three students use their L2 (Norwegian) orally in class. Anna and Lin have lived in Norway most of their lives, and their everyday knowledge about their L1 has been reduced to a language they occasionally use at home. Hence, they do not have an academic language to build on in their L1. Leila is in a comparable situation, as she arrived in Norway from Syria at an age when she was beginning to read and write. Her knowledge of Arabic does not include functional academic words. Thus, the use of identity texts in this study emphasises the potential for the students to develop a science identity that is ubiquitous in their learning process. For example, the texts allow the students to explore the connection between sensory experiences through drawing and participation in an oral dialogue ( and excerpt 3). Also, they offer the students an opportunity to express emotions and familiar experiences related to the science topic (excerpt 7), and they play a prominent role in facilitating dialogues around concepts with various meanings ( and excerpt 2). We see these identity texts as a ‘first step’ for the implementation of inclusive teaching practices allowing students to use a broad array of resources in their struggle to create relevance and meaning about abstract phenomena and processes in science. Also, they constitute a potential for L1 students (Cummins, Citation2021), as they too need the opportunity to connect various experiences and interests to science topics. Identity texts and following dialogues can therefore be appropriate to use for all students.

The analysis of the textual meta-function indicates that the strategy to deal with challenging concepts is to draw (). This emphasises the importance of allowing students to make active choices about how to express science knowledge. Multilingual students in the process of learning both the L2 and science often lack sufficient words to explain academic issues, and therefore opportunity to vary between different modes is of major importance (Williams et al., Citation2019).

Approaching the science content differently

The analysis of the ideational meta-function reveals differences in the three students’ approaches to the science topic. Anna and Leila highlight relevant science factors as main ‘participants’ (soundwaves, guitar string, skull, parts inside the ear). They perceive these factors as relevant (excerpts 4 and 6), although not necessarily familiar with the scientific phenomenon. Lin`s expression illustrates the importance of emotions as part of science education in primary school (Siry & Brendel, Citation2016). Her meaning-making revolving around the ideational dimension is strongly connected to her sensory experiences; the pronoun ‘I’ is highlighted (), her ear is a significant participant in the drawing of soundwaves, vibration is related to rumbling stomach (), and she highlights herself and her emotional experiences when she is expressing knowledge about plants ( and excerpt 7). This implies that her way to ‘grab the science topic’ goes through her own experiences and interests. Creating science identity texts and taking part in a following dialogue about her expressions exemplifies one way for her to process science.

Anna and Leila, on the other hand, are able to link the science topic to a TV programme (excerpts 4 and 6). They share the experience of watching the same TV programme and chose to highlight the connection between the animations and explanations in the TV programme with their mental models expressed through metaphors. They utilise a variety of semiotic resources (Kress, Citation2010), illuminating the importance of expanding scientific understanding through various modalities (Williams et al., Citation2019). However, the interpersonal part of the analysis reveals that the content expressed in the identity texts, to some extent, contradicts the content in the oral mode. This is illustrated as the drawings made by the two girls highlight the subject-specific content from the school situation ( and 4), and the oral dialogue revolves around experiences with the content from an arena outside school (excerpt 4). Both Anna and Leila chose to use the modes from the TV show in their oral negotiation of the subject-specific content. Their informal talk in the co-generative dialogues facilitates how they draw on a wider variety of semiotic resources than drawing alone. Lin does not express experiences from outside school, depriving her of building on everyday experiences in her negotiation of soundwaves (excerpt 5). Although her written and oral expression is highly redundant, she struggles with the connection between the scientific phenomenon and appropriate resources to build on.

The communication of the task encouraged the students to make their own choices about what to express in their identity texts (Cummins & Early, Citation2011). Still, they largely focus on teaching resources, mainly written products. The students seem unfamiliar with performing tasks allowing them to use creative expressions to connect the topic to experiences outside the science classroom. Their positioning as knowledgeable and enacting agency is limited, leading to reduced opportunities to experience engagement and meaning-making (Siry et al., Citation2016).

Identity texts and social semiotic theory as a tool for science teachers

The study emphasises the need for a teaching practice providing students with an opportunity to approach science by involving various resources, also when it is not visible to the teacher that there are multilingual students who would benefit from this in the classroom. Below, we highlight the importance of communicating a task involving identity texts, and we are pointing at the importance of building the students’ skills in utilising a wide range of semiotic resources in identity texts. Also, we reflect on how social semiotics can provide teachers with a tool to interpret students' expression of knowledge in scientific identity texts combined with dialogues.

The communication of the task contributes to framing the students’ attention. The data material in this study indicates that the students perceived their mission as producing an answer strongly connected to the content taught in school. For example, the first task given to the students was open, encouraging them to reflect upon their associations with science. The communication of the task guided Lin to focus on air and sound, which was the current science topic for the school class (). In the following dialogue, she seems satisfied about referring to sound and air but without signs of enthusiasm, like smiling, pointing, elaborating and influencing the dialogue with unsolicited utterances. She does not seem to have available tools to make the science topic relevant. The mediation of the task can partly explain this, but also the encultured school tradition. Her need to connect the science topic to emotional and sensory experiences is neither nurtured nor structured into strategies with the potential to discover core knowledge around scientific phenomena. However, her identity texts and oral participation in the co-generative dialogues (Tobin & Roth, Citation2006) provide valuable information for science teachers. Her participation indicates a potential to facilitate her learning processes by encouraging her to utilise resources from a wider array of arenas. Similar situations count for Anna and Leila, which potentially could benefit from including resources from language, TV programmes and experiences from home and other countries in various student texts. Involving experiences from arenas outside school is a matter of practice.

Conclusion and Implications

The students' experience of relevance and ability to connect content to individual experiences, languages and interests is ubiquitous for transformative learning. However, it also evokes challenges in the science classroom, as it implies that students at some point are encouraged to make their own choices in how to process and express science content. Our study emphasises that various tasks that allow the students to express how they perceive science content while negotiating identity and using a broad array of resources constitute an important part of transformative learning processes. As one of several tasks included in inquiry-based teaching units, the data material in this study indicates that there is an unused potential in allowing students to utilise their resources in science products. Explicit practice in exploring words, concepts, visualisations, constructions and oral interactions with peers can provide opportunities to facilitate meaning-making. This kind of work should not occupy extra time for the teacher, but rather it should be a part of the subject-specific work for the students. However, knowledge and skills in acknowledging the student's negotiation of subject-specific matter intertwined with individual resources are of significant importance for the teacher. Often, science teachers are not aware of the strategies multilingual students utilise to camouflage the experience of difficult words and concepts, or the various backgrounds building the basis for the students' meaning-making processes. Valuing student participation involving various languages, identities, experiences, and interests potentially plays a major role to students creating meaning in science.

Ethics statement

The study is approved by Sikt – Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. The informants participating in the study have agreed to take part, and they are anonymised.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Magical Body (Den magiske kroppen) is a well-known TV series in Norway, directed towards primary-school children. It consists of 15 episodes explaining central organs of the human body.

References

- Book, P. (2022). To flerspråklige elevers utøvelse av aktørskap i fagsamtaler i naturfag [Two multilingual students’ enactment of agency in discussions about science]. Acta Didactica Norden, 16(3), https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.9564

- Cummins, J. (2014). Beyond language: Academic communication and student success. Linguistics and Education, 26, 145–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.006

- Cummins, J. (2019). Identity texts and academic achievement: Connecting the dots in multilingual school contexts (3rd ed., Vol. 49, pp. 555–581). Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages. https://inn.instructure.com/courses/10207/files?preview=884668

- Cummins, J. (2021). Rethinking the education of multilingual learners: A critical analysis of theoretical concepts (Vol. 19). Multilingual Matters.

- Cummins, J., & Early, M. (2011). Identity texts: The collaborative creation of power in multilingual schools. Trentham.

- Cummins, J., Hu, S., Markus, P., & Kristiina Montero, M. (2015). Identity texts and academic achievement: Connecting the dots in multilingual school contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 49(3), 555–581. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/tesq.2015.49.issue-3

- Danbolt, A. M. V. (2020). «Den dialogen du har, det er den som er opplæring.» Læreres oppfatninger av muntlig samhandling med flerspråklige elever i naturfagundervisning. [“The dialogue you have, that is the teaching”. Teacher’s perceptions about oral interactions with multilingual students in science]. NOA – Norsk som andrespråk, 36(2), 65–82.

- Duff, P. A. (2002). The discursive co-construction of knowledge, identity, and difference: An ethnography of communication in the high school mainstream. Applied Linguistics, 23(3), 289–322. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/23.3.289

- European Commission, Y. (2017). Rethinking language education in schools. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Garcia, O., & Wei, L. (2013). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan UK. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/hilhmr-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4000846.

- Halliday, M. (2014). An introduction to functional grammar. Routledge.

- Halliday, M. A. K. (2006). Language as social semiotic. Communication Theories, 2, 33–54.

- Hodge, B., & Kress, G. R. (1988). Social semiotics. Cornell University Press.

- Jewitt, C., Kress, G., Ogborn, J., & Tsatsarelis, C. (2001). Exploring learning through visual, actional and linguistic communication: The multimodal environment of a science classroom. Educational Review, 53(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910123753

- Knain, E., Fredlund, T., & Furberg, A. (2021). Exploring student reasoning and representation construction in school science through the lenses of social semiotics and interaction analysis. Research in Science Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-020-09975-1

- Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. Routledge.

- Kress, G. (2020). Transposing meaning: Translation in a multimodal semiotic landscape. In M. Boria, Á Carreres, M. Noriega-Sánchez, & M. Tomalin (Eds.), Translation and multimodality (1st ed., pp. 24–48). Routledge.

- Kress, G., & Leeuwen, T. V. (2021). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Kress, G., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2002). Colour as a semiotic mode: Notes for a grammar of colour. Visual Communication, 1(3), 343–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/147035720200100306

- Lehre, A.-C. W. G., & Nilsen, T (2021). Språk i hjemmet og naturfagprestasjoner fra TIMSS 2015 til TIMSS 2019 [Language at home and performance in science in TIMSS 2015 to TIMSS 2019]. In T. Nilsen, & H. Kaarstein (Eds.), Med blikket mot naturfag: Nye analyser av TIMSS 2019 – data og trender 2015–2019 [Looking to science: New analysis of TIMSS 2019 – data and trends 2015–2019] (pp. 165–182). Universitetsforlaget.

- Lemke, J. L. (2001). Articulating communities: Sociocultural perspectives on science education. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(3), 296–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2736(200103)38:3<296::AID-TEA1007>3.0.CO;2-R

- Maagerø, E. (1998). Hallidays funksjonelle grammatikk – en presentasjon [Halliday’s functional grammar – a presentation]. In P. Coppock, E. Maagerø, & K. L. Berge (Eds.), Å skape mening med språk [Creating meaning with language] (pp. 33–63).

- Rajendram, S., Burton, J., & Wong, W. (2022). Online translanguaging and multiliteracies strategies to support K-12 multilingual learners: Identity texts, linguistic landscapes, and photovoice. TESOL Journal, 13(4), e685. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.685

- Siry, C. (2020). Dialogic pedagogies and multimodal methodologies: Working towards inclusive science education and research. Asia-Pacific Science Education, 6(2), 346–363. https://doi.org/10.1163/23641177-BJA10017

- Siry, C., & Brendel, M. (2016). The inseparable role of emotions in the teaching and learning of primary school science. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 11(3), 803–815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-016-9781-1

- Siry, C., & Gorges, A. (2020). Young students’ diverse resources for meaning making in science: Learning from multilingual contexts. International Journal of Science Education, 42(14), 2364–2386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1625495

- Siry, C., Wilmes, S. E. D., & Haus, J. M. (2016). Examining children’s agency within participatory structures in primary science investigations. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 10, 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.01.001

- Svennevig, J. (2020). Språklig samhandling: Innføring i kommunikasjonsteori og diskursanalyse [Linguistic interaction: Introduction to communication and discourse analysis] (3rd ed.). Cappelen Damm akademisk.

- The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. (2023). In English. About Norwegian Education and the Curriculum. https://www.udir.no/in-english/.

- Tobin, K. G., & Roth, W.-M. (2006). Teaching to learn: A view from the field. Sense Publishers.

- Wanselin, H., Danielsson, K., & Wikman, S. (2021). Analysing multimodal texts in science – a social semiotic perspective. Research in Science Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-021-10027-5

- Williams, M., & Tang, K.-S. (2020). The implications of the non-linguistic modes of meaning for language learners in science: A review. International Journal of Science Education, 42(7), 1041–1067. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2020.1748249

- Williams, M., Tang, K.-S., & Won, M. (2019). ELL’s science meaning making in multimodal inquiry: A case-study in a Hong Kong bilingual school. Asia-Pacific Science Education, 5(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41029-019-0031-1

- Zaidi, R., & El Chaar, D. (2022). Identity texts: An intervention to internationalise the classroom. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 17(3), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2020.1860060

- Zapata, G. C., & Ribota, A. (2021). The instructional benefits of identity texts and learning by design for learner motivation in required second language classes. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 16(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2020.1738937