ABSTRACT

Higher education institutions are trying to optimise course designs. During COVID-19, distance education became the primary teaching format worldwide, and current studies suggest that the online experience may have changed students’ learning format preferences, which prior to the pandemic leaned toward face-to-face (F2F) learning. This study aimed to (1) examine students’ stated and revealed (i.e. actual attendance) learning format preferences when provided F2F, synchronous online, and asynchronous online attendance options and (2) examine students’ perceived benefits and pitfalls of the three learning formats before and after their learning experience. Overall, 158 undergraduate students attended hybrid physics courses, allowing them to attend F2F, synchronously online via Zoom, or asynchronously online via lesson recordings. After the first lesson, students answered closed and open-ended questions about their stated learning format preferences. At the end of the course, students filled in their revealed learning format and answered open-ended questions regarding their motives. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted. Most students initially preferred to learn F2F, but many shifted to a hybrid format, combining F2F and online learning. Thematic analysis revealed themes concerning the benefits and pitfalls of each learning format, and interviews uncovered students’ behaviour.

Introduction

Already two centuries ago, thousands of students engaged in distance education (Pittman, Citation2003). In the beginning, it was through textbooks and correspondence, but it has evolved to computer-based online learning starting from the creation of personal computers during the 1980s. The rise of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOC) increased the demand for online learning; where in 2012 The New York Times published an article named ‘The Year of the MOOC’, following the sharp rise of MOOC companies such as edX and Coursera (Pappano, Citation2012). Nevertheless, even though universities adopted online courses, face-to-face (F2F) remained the main teaching format in most higher education institutions (Moores et al., Citation2019). It was not until COVID-19 pandemic that led most universities to teach, at least for a certain time, online (NCES, Citation2022). Yet, after the pandemic, the primary teaching format in many universities went back to F2F. Still, a rise in absenteeism from classroom sessions has been observed, attributed primarily to questions regarding the necessity and benefits of F2F attendance in light of readily available online content (e.g. previous recordings of the course, online resources through other universities, etc.) (Traphagan et al., Citation2010; Uekusa, Citation2023).

Several benefits and pitfalls of online learning have been reported. In online learning, students have time and space flexibility (Bakia et al., Citation2012), and those who are weaker in verbal communication can better express themselves in online modes (e.g. online forums) (Stern, Citation2004). Furthermore, if the online courses are asynchronous (e.g. video lessons), students can control the pace of the lesson and review the materials (Broadbent & Poon, Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2013). Nevertheless, online learning requires students to be more responsible for their learning process (Kizilcec et al., Citation2017) and requires higher self-discipline (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020). During and after COVID-19, students felt boredom, anxiety, frustration, isolation, negative mood, and decreased motivation (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020; Besser et al., Citation2022), were easily distracted by technologies (e.g. smartphones) (Melgaard et al., Citation2022; Serhan, Citation2020) and experienced a decrease in concentration (Aristovnik et al., Citation2020).

Several studies have shown that many students preferred learning F2F before and during COVID-19 (e.g. Barak et al., Citation2016; Jaggars, Citation2014; Price Banks & Vergez, Citation2022). Nevertheless, other studies suggest that the online learning experience during the pandemic may have changed students’ preferences. More Students want to benefit from both worlds, traditional F2F learning and online learning environments (e.g. Bećirović & Dervić, Citation2023; Castro & George, Citation2021; Gherheș et al., Citation2021; Guppy et al., Citation2022; Haningsih & Rohmi, Citation2022).

There are two main ways of measuring students’ preferences. It is possible to ask the students their preference (e.g. Price Banks & Vergez, Citation2022), also known as a stated preference, or alternatively, provide an environment in which they need to act by choosing one of several options (e.g. Barak et al., Citation2016), also known as revealed preference (Samuelson, Citation1948). Revealed preference is often regarded as preferable to stated preference because of the consequences and costs of the students’ actions. Nevertheless, it is also possible that students’ attendance choice is affected by other constraints (e.g. time\family\work constraints) and does not reflect their ideal learning preference. Thus, using mixed methodologies of stated preferences and revealed preferences may provide a better picture of the benefits and pitfalls students perceive for each learning format (Ben-Akiva & Morikawa, Citation1990; Elliott & Neal, Citation2016; Foddy & Foddy, Citation1993, pp. 3–4).

The online learning experience during COVID-19 may have given students a new perspective regarding their learning format preferences. Studies in the pre-COVID-19 era may be limited by the fact that many students have not experienced online learning for an extensive time, which may affect their beliefs, learning behaviour, and preferences (Shen et al., Citation2013; Wang et al., Citation2013). On the other hand, studies conducted during COVID-19 confinement also impose situational context limitations. During this period, there was no choice but to learn online, which may influence students to oppose or favour online learning. Resistance to online learning during COVID-19 could have been caused by the decrease in well-being due to the confinement (Gonzalez et al., Citation2020; Willy & Maarten, Citation2012) and by courses that were often characterised by a hasty shift to online learning due to the circumstances, not allowing adequate preparation of the courses, resulting in a lower quality of online instruction (del Arco et al., Citation2021; Iesalc, Citation2020). However, students may also favour online learning due to the prolonged constraints of the pandemic, where students were more assimilated to the situation, resulting in adaptive online learning behaviour (Ramos-Morcillo et al., Citation2020). This adaptation and change of behaviour may change their preferences, i.e. preference may not only influence behaviour, but behaviour may also influence preference (bidirectional) (Ariely & Norton, Citation2008). Given that almost all students gained online experience during the pandemic and F2F learning is no longer a constraint, the era of post-COVID-19 allows a cleaner examination of their learning format preferences.

This research aims to contribute by examining students’ stated and revealed learning format preferences when given a choice between three learning formats: face-to-face (F2F), synchronous online, and asynchronous online lessons. Furthermore, this research aims to examine students’ perceived benefits and pitfalls of these three learning formats before and after their experience in the course. We believe that in order to combine these three learning formats into a hybrid course, it would be beneficial to understand the benefits and pitfalls of each learning format beforehand, using a controlled research environment (i.e. an approach that provides precisely the same content through different learning formats).

The evolution and rise of distance education

The basic concept of distance education involves the teacher teaching content while the students learn at another time or in another space (Moore et al., Citation2011; Sherry, Citation1995). Distance education’s earliest record states to 1728 when Caleb Phillips advertised in the Boston Gazette that he could teach any person in the US the shorthand art by sending weekly lessons via mail, ending with a statement of ‘be as perfectly as those that live in Boston’ (Kentnor, Citation2015; Philipps, Citation1728). Universities used correspondence education to teach courses designated to adults with obligations (e.g. family) or financial constraints (Bozkurt, Citation2019; Kentnor, Citation2015). Then, the phenomena expanded by offering full-distance education degrees, first known in 1858 by the University of London (Qayyum & Zawacki-Richter, Citation2018). The second age of distance education began in the 1920s with visual-auditory multimedia, i.e. studying by audiotape, radio, television, and teleconference (phones). Finally, the third age of distance education began in the 1980s with the invention of personal computers, smartphones, and the internet (Bozkurt, Citation2019; Kentnor, Citation2015; Saykili, Citation2018). During the 2010s, online courses received great public attention with the rise of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). MOOCs enable adult learners who are far from campus and have work and family obligations for lifelong learning, an essential condition for twenty-first-century skills as citizens and workers (Council, Citation2012; Kara et al., Citation2019; Wolters, Citation2010). Moreover, the introduction of free MOOCs from top universities had put into question the future path of higher education (Billington & Fronmueller, Citation2013; Dennis, Citation2012). In 2018, 101 million students were registered to MOOCs, but this number more than doubled in 2021, with around 220 million students signed to one of the 20,000 MOOCs delivered by 950 universities (Shah, Citation2019, Citation2021). Nowadays, universities use MOOCs as part of their curriculum, and some programmes provide a full degree (Papadakis, Citation2023).

The evolution and rise of distance education provided new formats of learning. Learning formats can broadly be classified as physical (F2F), virtual (online), or both (Moore et al., Citation2011). Virtual (online) environments include synchronous and/or asynchronous online learning. Synchronous lessons consist of teleconference meetings (e.g. via Zoom) where the teacher and students attend a class simultaneously but have flexibility in space. Students who feel less comfortable in class can experience a better learning space while still gaining pedagogical opportunities found in face-to-face lessons (e.g. a student-centred environment for real-time discussions and feedback, increased sense of commitment, etc). Asynchronous lessons consist of presentations, online forums, and/or video lectures. In this case, students have flexibility in time and space but less immediate feedback. This may decrease their pressure from responding on the spot to their classmates and teachers and increase their critical thinking by giving them more time to respond/think (Amiti, Citation2020; Fabriz et al., Citation2021; Greenhow et al., Citation2022).

COVID-19 has struck education worldwide with no preparation time, leading educational institutions and lecturers to decide their online instructional strategy with minimal time. During the first wave of COVID-19, in the Spring of 2020, Aristovnik et al. (Citation2020) examined 30,383 students from 62 countries. They found that the most common online learning in higher education was led by synchronous video conference meetings (59.4%) and less commonly by asynchronous material, such as presentations (15.2%), video recordings (11.6%), and written communication (e.g. forums) (9.1%). Right before the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2017–2019, 33-36% of higher education students in the US enrolled in online courses (NCES, Citation2021), out of which 80% were undergraduates (Allen & Seaman, Citation2017). However, in the pandemic outbreak, in the spring of 2020, 94% of learners worldwide were affected by the lockdowns and closure of schools (UN, Citation2020), and 84% of US undergraduate students learned partially or fully online (Cameron et al., Citation2021). Thus, most higher education institutions worldwide have temporarily transformed into online learning formats. While the COVID-19 lockdowns gradually decreased, online learning remained more prevalent than before the pandemic. After the peak of the pandemic, in the fall of 2021, 59% of higher education students in the US enrolled partially or fully in online courses (NCES, Citation2022). Nevertheless, the learning format of many universities returned to be mostly F2F.

Learning performance in F2F vs. online learning

Which learning format is more effective – online or F2F? Research findings are not conclusive. In a meta-analysis between 1996 and 2008, Means et al. (Citation2009) found that students who took all or part of the course online performed better, on average, than those learning only F2F. Likewise, in the study of Barak et al. (Citation2016), 84 students could choose to learn the course ‘Educational Psychology’ fully online or F2F, while the lectures and the assignments are similar. Students who decided to learn it online excelled in their scores more than those who chose to learn F2F.

Nevertheless, other studies found F2F learning more effective than online learning. Powers et al. (Citation2016) and Adams et al. (Citation2015) examined courses delivered as fully F2F and hybrid (partially F2F and partially online) and found that students who attended fully F2F showed better learning performance in grades during the term (Adams et al., Citation2015; Powers et al., Citation2016), final examination (Adams et al., Citation2015), and completion rates of homework (Powers et al., Citation2016).

Also, there are no conclusive conclusions regarding the effectiveness of different online learning formats. Some studies show that students perform better if learning through online synchronous than in asynchronous learning (K. Duncan et al., Citation2016; Libasin et al., Citation2021). For example, Libasin et al. (Citation2021) examined, during COVID-19, students learning performance in math courses. They found that students performed better in courses that were delivered synchronously than those that were delivered asynchronously. However, other studies show better performance for asynchronous learning (e.g. Berry, Citation2017) or no significant difference between asynchronous vs. synchronous learning (e.g. Nieuwoudt, Citation2020). Even though there is inconclusiveness, studies show that students’ usage of online content (e.g. for reviewing the lesson) improves their performance, recommending a hybrid synchronous and asynchronous online learning approach.

Furthermore, some studies have indicated the need to personalise the learning format. A large-scale study by Cavanaugh and Jacquemin (Citation2015) covered 140,444 students learning in a large public university over the years 2010–2013. They found that although grade scores had little to no difference, less-struggling students performed better in online courses, and in contrast, those who did struggle performed better in F2F. Nortvig et al. (Citation2018) concluded in a literature review that students’ learning performance is not a function of the different learning formats (F2F, online) but rather the circumstances and is context-dependent.

Even though online learning during COVID-19 was correlated to lower students’ motivation and well-being, which negatively correlates to learning performance (Cho & Heron, Citation2015; Holzer et al., Citation2021; Luo et al., Citation2021), some studies found improvement in students’ performance during the pandemic (Gonzalez et al., Citation2020; Iglesias-Pradas et al., Citation2021). Gonzalez et al. (Citation2020) checked the learning performance of 458 students, where some students learned the courses pre-COVID-19 and others during COVID-19. They found that the students who learned the courses after the beginning of the pandemic confinement excelled in their test scores. They suggest that students’ improvement in their performance is related to the pandemic circumstances. Students had to be more responsible in their learning process, and the fear of losing an academic year from failing made them work harder to solve the challenges they were facing.

Students’ learning format preferences

Despite the rich research on students’ learning format preferences, the results are inconclusive. Some pre – and during COVID-19 studies found that most students prefer learning F2F to online (e.g. Barak et al., Citation2016; Jaggars, Citation2014; Price Banks & Vergez, Citation2022). For example, in the study of Barak et al. (Citation2016), when given a choice, out of 84 undergraduate students, two-thirds decided to learn the course F2F. In another study, Besser et al. (Citation2022) found a less positive experience from the COVID-19 synchronous online learning compared to F2F learning regarding stress, isolation, mood, relatedness, concentration, focus, and motivation.

In contrast, other studies found that students prefer online or hybrid courses. For example, Miller et al. (Citation2013) found that when allowed to choose between three learning formats (F2F, synchronously online, and asynchronously online via lesson recordings), two-thirds out of 161 students attended online. At the end of the course, 57% indicated that they preferred hybrid courses, 38% preferred fully online courses, and only 5% preferred fully F2F courses. Moreover, studies regarding students’ online learning experience during the pandemic indicate their desire to benefit from both worlds, traditional F2F learning and online learning formats (e.g. Bećirović & Dervić, Citation2023; Castro & George, Citation2021; Gherheș et al., Citation2021; Guppy et al., Citation2022; Haningsih & Rohmi, Citation2022).

Research goals and questions

This study aimed to examine students’ learning format preferences in the era of post-COVID-19. In order to have a more thorough understanding of students’ preferences, the study aimed to check their stated learning format preferences as well as their revealed learning format preferences (i.e. actual attendance patterns) when provided with equivalent F2F, synchronous, and asynchronous attendance options. Furthermore, this study aimed to reveal students’ perceived benefits and pitfalls of the different learning formats before and after their learning experience.

To achieve the research goals, the study implemented a teaching platform in physics higher education courses to support three learning formats that students may choose from: synchronous F2F, synchronous online, and asynchronous online. The lessons were identical, and there were no constraints of attendance throughout the course (i.e. a student may choose to learn by different formats during different lessons).

Derived from the research goals are the following research questions:

RQ1. What are students’ stated learning format preferences when allowed to choose between synchronous F2F, synchronous online, or asynchronous online learning?

RQ2. What are students’ revealed learning format preferences (i.e. actual attendance patterns) when allowed to choose between synchronous F2F, synchronous online, or asynchronous online learning?

RQ3. What are the perceived benefits and pitfalls of the three learning formats from students’ perspectives?

Method

Participants

In the academic year 2021–2022, 158 undergraduate students from the Technion – Israel Institute of Technology enrolled in one of six hybrid physics reinforcement courses. From all the students enrolling in the courses, 118 (58 males, 60 females, age mean = 22.9, SD = 2.13) answered all questionnaires (two questionnaires in total). Sixty-one students were in their first semester, 42 were in their second semester, and 15 were in their third semester or above. One hundred and seven students were unemployed, ten worked up to ten hours per week, and one worked above ten hours per week. Furthermore, 16 semi-structured interviews were conducted during the last two lessons of the course, aiming to represent all different learning attendance patterns. The university ethics committee approved the research, and the students volunteered to answer the questionnaires and signed a consent form.

Materials

The subjects of the reinforcement courses were ‘Mechanics’ or ‘Electricity & Magnetism’. ‘Mechanics’ courses are divided into regular (Mechanics) or advanced level (Mechanics+) courses, depending on students’ requirements by faculty (e.g. electrical engineering students are learning the advanced course, whereas mechanical engineering students are learning the regular course). ‘Electricity & Magnetism’ was taught only as an advanced course, mainly for electrical engineers. All the courses were reinforcement courses held beyond formal university lessons, consisting of 14–36 students per class (mean of 26.3 students per class, SD = 7.9). The students paid extra tuition for enrolling, and the price was calculated according to the number of hours (all the students paid the same price per hour). They could cancel their registration after the first lesson for any reason. The number of lessons per course may vary depending on the subject and starting date; accordingly, each lesson lasts between 3–4 hours. The first author taught all courses and had no connection to students’ grading.

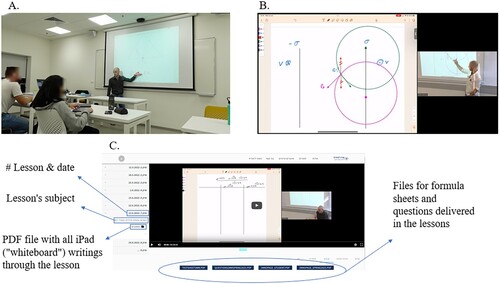

A teaching platform was designed to support three learning formats: synchronous F2F, synchronous online via Zoom, and asynchronous online via lesson recordings (see ). The lessons were held in a classroom containing (a) a camera that was filming the teacher, (b) a remote microphone, and (c) an iPad (touchscreen tablet) for an online ‘whiteboard’. Participants who attended F2F saw the iPad screen with a projector, whereas participants online saw it with a screen share. All the lessons were filmed and recorded. Up to 24 hours after class, the lesson recording was available on the course’s webpage, along with all writing given on the iPad as a pdf file.

Before the first lesson, students received an email informing them of the three formats in which they can participate: (1) F2F – arrive to class, (2) Zoom – watch synchronously online via Zoom, or (3) Lesson Recordings – watch the lesson asynchronously after the class. They were not obligated to one of the three formats and could change their decision throughout the course. Moreover, the students received a link to the course’s webpage. The webpage included the lesson recordings, PDF files of the tablet (‘whiteboard’) writings during the lesson, a formula sheet that summarises the theory and equations of the course, and a PDF file with all questions that will be presented during the classes.

Figure 1. Photos/Screenshots of: (A) face-to-face lesson, (B) synchronous online lesson via Zoom, (C) webpage for an asynchronous online lesson via lesson recording.

In terms of pedagogy, the lessons included explicit instruction as well as active learning. A typical lesson began with the teacher introducing the theorem and equations. Afterward, he demonstrated how to answer a question. Later, students practiced a similar question alone while the teacher was available for personal guidance and questions (this feature was available to the students arriving F2F and/or via Zoom). Lastly, the teacher solved the problems on the board.

Measures

Demographics

After the first lesson, demographic information was collected, including gender, age, semester in studies, and number of hours working for salary.

Stated learning format preference questionnaire

After the first lesson, students stated their learning format preferences. The questionnaire included two questions: (1) a closed-ended question, ‘In what learning format do you think you would like to learn during the course?’ where they can choose multiple answers from the following options: F2F, Zoom, lesson-recordings, or unsure; and (2) an open-ended follow-up question of their reason choosing so.

Revealed learning format preference (actual attendance) questionnaire

At the end of the course, students reported their learning format attendance per lesson (F2F, Zoom, lesson recordings). We compared the self-reporting results of the spring 2022 courses to our count of the attending students per learning format for each lesson. While we did not receive a perfect match, overall, Duncan’s Index of Dissimilarity average per lesson was 0.12 with a standard deviation of 0.02 (O. D. Duncan & Duncan, Citation1955), indicating a relatively low level of dissimilarity between the self-reported data and the actual attendance.

In addition, during the spring semester of 2022, after noticing that students use recordings even if they attend class, a closed-ended question was added ‘Are you using lesson recordings for reviewing the material?’.

Finally, the students answered three open-ended follow-up questions: (1) ‘For the lessons you attended F2F, what were the reasons for it?’, (2) ‘For the lessons you attended via Zoom, what were the reasons for it?’, and (3) ‘For the lessons you attended via lesson recording, what were the reasons for it?’.

Semi-structured interviews

Sixteen semi-structured interviews were conducted during the last lessons of the course, aiming to represent all different learning attendance patterns. The interviews consisted of open questions, seeking to discover more about students’ perspectives of the three learning formats and their preferences. The first questions were more general, such as ‘What is your opinion of learning F2F/Zoom/lesson recordings?’, ‘What are the difficulties/benefits of learning F2F/Zoom/lesson-recordings?’, and afterward more specific questions such as ‘What is your preference?’, ‘which one is more suited for you?’. If students’ attendance did not align with their preferences, they were asked to explain why. Finally, they were asked if their learning attendance in the course was coherent with their learning attendance in other courses and why. This approach aims to make a transition from students’ thoughts regarding the benefits and pitfalls of each learning format to their personal preferences and attendance patterns (Patton, Citation2014, p. 428).

Data analysis

Both authors analysed the open-ended questions and semi-structured interviews using thematic analysis to establish internal validity (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The first author’s involvement as the courses lecturer enabled the analysis of the data from a more holistic point of view (Mayring, Citation2004).

Thematic analysis followed (1) the essentialist method, also known as the realist method, i.e. the authors identified the themes through the participants’ answers without trying to uncover their meaning through social and cultural context. This method implies that the analysis focused more on students’ motivation and thoughts, (2) semantic approach, i.e. straightforward interpretation rather than uncovering ideas behind the text, such as participants’ assumptions and ideologies, and (3) Inductive linkage, i.e. themes were identified by the data and codes derived (bottom-up approach), rather than finding themes from a theory perspective. Inductive analysis may provide a more detailed description of the benefits and pitfalls of each learning format and the reasons for attendance behaviour, whereas a theory-based analysis may provide a more detailed analysis of the aspects it covers. We selected the inductive analysis approach as we did not want to limit the themes to a specific theory (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Even though all the questions in the questionnaires referred to the benefits of the learning format (e.g. ‘For the lessons you attended F2F, what were the reasons for it?’), some students stated reasons that are not directly related to the benefit of the learning format but rather to the pitfalls of the other learning formats. In other words, while some students attended a learning format because of its benefits, others attended it because of the pitfalls of the other learning formats (e.g. attending F2F because of distractions in online learning). Thus, we divided the themes into benefits and pitfalls. After agreeing on the themes, we counted the occurrences of each theme at the beginning and at the end of the course.

In addition, we conducted 16 semi-structured interviews to further investigate the benefits and pitfalls and uncover students’ behaviour. The interviews were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis as described above.

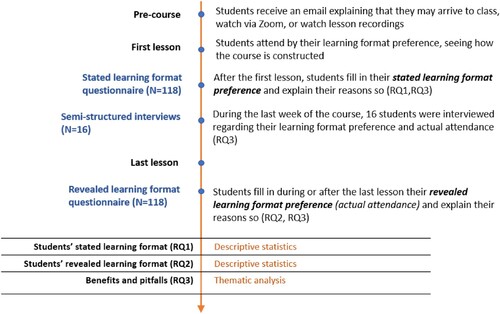

Procedure

Several days before the beginning of the course, students received an email with all relevant material and links, explaining that they may decide if they prefer to arrive at class F2F, attend via Zoom, or watch the lesson recordings. After experiencing the first lesson, the students completed the stated learning format preference questionnaire. During the last lessons, the first author conducted semi-structured interviews. Finally, during or after the last lesson, students completed the revealed learning format preference questionnaire. See for an overview of the procedure.

Results

Students’ learning format initial stated preferences (RQ1)

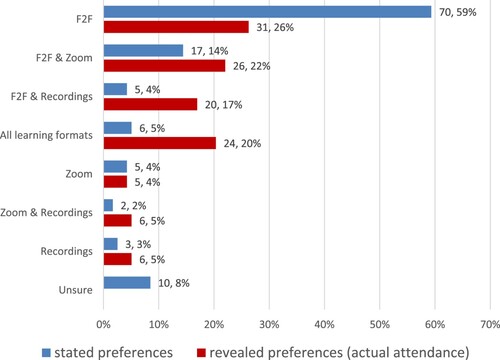

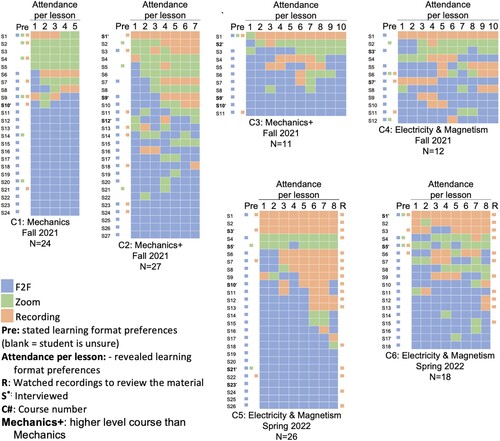

To answer the first research question (‘What are students’ stated learning format preferences when allowed to choose between synchronous F2F, synchronous online, or asynchronous online learning?’), we used the stated learning format preference questionnaire. After the first lesson, the students answered the closed-ended question, ‘In what learning format (F2F, Zoom, lesson recording, unsure) do you think you would like to learn during the course?’. The columns under ‘pre’ in present students’ stated learning format preferences after the first lesson across all the courses.

Figure 3. Students’ stated and revealed learning format preferences during the course, per course. Each row represents a student.

Overall, at the beginning of the course, 98 out of 118 students (83%) reported a preference to attend fully or partially F2F, whereas only 38 out of 118 students (32.2%) reported a preference to attend fully or partially online. Specifically, across all courses, out of 118 students, 70 preferred learning only via F2F, 5 only via Zoom, 3 only via lesson recordings, 30 preferred a combination, and 10 were unsure. Of the 30 students who preferred a combination, 6 students preferred to attend by all three learning formats, 17 students by F2F and Zoom, 5 students by F2F and lesson recordings, and 2 students by Zoom and lesson recordings (see ).

Students revealed learning format preferences (i.e. actual attendance patterns) (RQ2)

To answer the second research question (‘What are students’ revealed learning format preferences (i.e. actual attendance patterns) when allowed to choose between synchronous F2F, synchronous online, or asynchronous online learning?’), we used the revealed learning format preference questionnaire. At the end of the course, students filled in their learning attendance format per lesson. The columns under ‘attendance per lesson’ in present students’ actual attendance across all the courses.

Overall, students’ attendance throughout the course revealed that 101 out of 118 students (85.6%) attendance patterns included F2F learning, and 87 out of 118 students (73.7%) attendance patterns included online learning in the course. Specifically, forty-two students attended via only one of the learning formats during the course (31 F2F, 5 via Zoom, and 6 via lesson recordings), 52 students attended via two learning formats (26 via F2F & Zoom, 20 via F2F & lesson recording, and 6 via Zoom & lesson recordings), and 24 students attended via all three learning formats (see ).

In addition, during the spring semester of 2022, after noticing that students use recordings even if they attend class, a closed-ended question was added ‘Are you using lesson recordings for reviewing the material?’. Out of 44 students, 28 students (64%) indicated they used the recordings for reviewing the material (see , ‘R’ column, across spring 2022 courses).

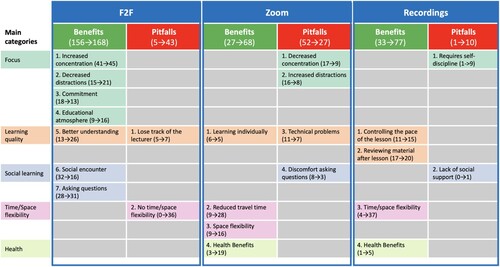

The perceived benefits and pitfalls of the three learning formats (RQ3)

To answer the third research question (‘What are the perceived benefits and pitfalls of the three learning formats from students’ perspectives?’), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was conducted on students’ answers to: (1) open-ended questions from the stated learning format preference questionnaire, (2) open-ended questions from the revealed learning format preference questionnaire, and (3) the 16 semi-structured interviews.

After the first lesson, students stated their learning format preference and were then asked a follow-up open-ended question of ‘why?’. At the end of the course, students stated their revealed learning format and were then asked three follow-up open-ended questions: (1) ‘For the lessons you attended F2F, what were the reasons for it?’, (2) ‘For the lessons you attended via Zoom, what were the reasons for it?’, (3) ‘For the lessons you attended via lesson recording, what were the reasons for it?’ (See for the conclusion of the categories and themes).

Figure 5. Themes for each learning format by benefits and pitfalls divided into categories. The numbers (#pre → #post) represent the occurrences of each theme at the beginning and at the end of the course.

The benefits and pitfalls of learning F2F

Students reported seven benefits of learning F2F that fall into three categories: focus, learning quality, and social learning. Under the category of focus we identified four themes: (1) increased concentration (e.g. ‘ … it was easier for me to come F2F, I don’t have to trust myself to concentrate, it’s automatic’.); (2) decreased distractions (e.g. ‘at home I’m … being on the phone, going to the fridge to get a snack … ’); (3) increased sense of commitment (e.g. ‘forcing me to leave the house’); (4) educational atmosphere (e.g. ‘there is a learning atmosphere in the classroom’). Under the category of learning quality we identified one theme: (5) better understanding (e.g. ‘I internalize the material better’). Under the category of social learning we identified two themes: (6) Social encounter (e.g. ‘I participate in the discussion’); (7) asking questions (e.g. ‘I’m more comfortable asking questions when I’m in class’).

Nevertheless, students also reported two pitfalls of learning F2F that fall into two categories: Learning quality, and time/space flexibility. Under the category of learning quality we identified one theme: (1) lose track of the lecturer (stop understanding) (e.g. ‘I had a gap in the course, so I chose to complete it first and then watch the recordings to strengthen my understanding’.). Under the category of time/space flexibility we identified one theme: (2) no time/space flexibility.

The benefits and pitfalls of synchronous learning via Zoom

Students reported four benefits of learning via Zoom that fall into three categories: learning quality, time/space flexibility, and health. Under the category of learning quality, we identified one theme: (1) learning individually (e.g. ‘While solving exercises alone, I put on mute so that there is no noise’.). Under the category of time/space flexibility we identified two themes: (2) reduced travel time (e.g. ‘Save time it takes to get to the university and back’); (3) space flexibility (e.g. ‘rainy weather’). Under the category of health we identified one theme: (4) health benefits (e.g. ‘I’m in a risk group so because of the fear of COVID-19 I don’t leave the house’).

Nevertheless, students also reported four pitfalls of learning via Zoom that fall into three categories: Focus, learning quality, and social learning: Under the category of focus we identified two themes: (1) decreased concentration (e.g. ‘When I’m alone at home … it’s easier to get lost and lose concentration’.); (2) increased distractions (e.g. ‘ … there is a lot of “dead” time in the course where you should try to solve exercises, but in reality, I retire to the phone, etc’.). Under the category of learning quality we identified one theme: (3) technological problems (e.g. ‘ … Even if it hangs for seconds, I feel like I’ve lost the lecturer’). Under the category of social learning we identified one theme: (4) discomfort asking questions (e.g. ‘I am more comfortable asking questions … face to face than behind a screen’.).

The benefits and pitfalls of asynchronous learning via lesson recordings

Students reported four benefits of learning via lesson recordings that fall into three categories: learning quality, time/space flexibility, and health: Under the category of learning quality we identified two themes: (1) controlling the pace of the lesson (e.g. ‘You can stop and try alone. If you need, you can run the video to get a hint’); (2) allows reviewing the materials (e.g. ‘I watched the recordings of the lessons after the lesson, in addition to my participation in the class … only the parts I … didn’t understand. I plan to repeat important parts … even before the test’.). Under the category of time/space flexibility we identified one theme: (3) time/space flexibility (e.g. ‘Stop attending for most of what can be completed by recordings in order to allow me to manage my own time with as few external factors as possible to plan my own learning schedule’). Under the category of health we identified one theme: (4) health benefits.

Nevertheless, students also reported two pitfalls of learning via lesson recordings that fall into two categories: Focus and social learning: Under the category of focus we identified one theme: (1) requires self-discipline (e.g. ‘There were times when I thought of watching … the recording, but I know that in most cases I am not responsible, and there is a big chance that I will not complete the lesson’). Under the category of social learning we identified one theme: (2) lack of social support (e.g. ‘(zoom is) better than recording because you can take an active part’).

Explaining students’ attendance patterns through interviews

We conducted 16 semi-structured interviews to further investigate the benefits and pitfalls and uncover students’ behaviour. The interviewees were specifically selected to represent a variety of learning formats attendance. Interviewees are represented by (C#-S#), indicating course’s and student’s number (see ).

Students attending mostly F2F throughout the course (C1-S10, C3-S9, C3-S10, C5-S23). These students attended the course mostly via F2F. Benefits of F2F included increased focus (increased concentration, decreased distractions, commitment, educational atmosphere), and social learning (asking questions and social encounters). As C5-S23 indicates:

I like that there is an immediate response … You can immediately ask, straight away if something doesn’t work out, it works out for me a few minutes later. I think that when there is a person, we always become more focused, at least I am. In the classroom, the atmosphere makes you concentrate …

In Zoom I feel that it is more difficult to ask questions … in class, it is more, I don’t know if more intimate, but I feel more comfortable asking questions. And even if I ask and still don’t understand, then it’s a matter of body language, you see on me if I don’t understand a certain question and I make a face, and I don’t say again that I don’t understand because it’s hard to say ‘Okay, I still don’t understand’ and it also creates frustration.

Because while being alone there are also interruptions and it turns out that I spread the lessons. Even if, for example, I watch the recordings, then I stop more, or I do other things and then miss, and even if I use the time to complete lessons, at the end, I get a gap in things.

Because the lectures are full and people don’t wear masks … when there was a high infection rate (COVID-19), even then, I was not at home. I came here (the university) and saw via Zoom … I am in a learning space, people are around me, I have nowhere to run … I have no choice, I have to finish.

Student C5-S21 preferred to learn via Zoom, but he knew the students arriving at this class and thus chose to sit with them during the lesson.

Students attending mostly Synchronouslly (i.e. zoom) throughout the course (C3-S2, C4-S3, C5-S5, and C6-S5). These students attended most of the lessons via Zoom. Student C3-S2 at first preferred arriving at all courses F2F, but her attendance depended on the number of lessons per day. Reducing travel time was more efficient for short learning days, and she attended via Zoom, but for full learning days she attended F2F. However, this pattern has changed after being sick from the flu, finding out that she can manage learning even full days via Zoom, making it her primary attendance:

At first, I was only at the university until December, except for a few days when I had four hours, so I don’t travel for four hours. But I have days … when I study from 8:30 am to 9 pm, so I did go … But from about December I got the flu, and I didn’t come anymore and I was only at Zoom, with the flu, and I saw that it worked out for me. I haven’t been since December.

Maybe at home now I need to work more on understanding the material by myself; I’m more comfortable if I see things in front of my eyes (F2F) … when you are in the classroom, there is the atmosphere, so here I have to spend more time to get into the atmosphere of learning.

Students C4-S3, C5-S5, and C6-S5 attended most of the course via Zoom. The most beneficial aspect of deciding so was because of the time given during the lesson for self-practice. For all of them, recordings were not a good option in this circumstance because they were aware that they did not hold the self-discipline required to solve the self-practice questions. Therefore, attending via Zoom gave them the ideal combination of reducing travel time (vs. F2F) and staying focused and participating (vs. recordings). C5-S5 indicates:

I don’t see myself that if I now see a recording, I will stop and try to solve 10 minutes, … Here (in Zoom) … I have to solve, I have to take an active part in the class, even if I’m not there physically. That’s why I came to this course, to practice and gain new learning skills …

Students attending mostly Asynchronously (i.e. via recordings) throughout the course (C2-S1, C5-S3, and C6-S1). Interviewees C2-S1 and C5-S3 attended the course mostly asynchronously online via recordings. They also indicated that they have learned asynchronously online in any academic course (when available). However, both interviewees realised that asynchronous learning was beneficial only after experiencing it. Interviewee C5-S3 attended one course in the open university before arriving at his current university. He realised that learning from a recording was much more suitable for him than attending class. Interviewee C2-S1 was learning in the preparatory school before being accepted to the university, and COVID-19 confinement gave him no choice but to learn online. After finding out that he excelled in his grades, he had the confidence and realisation that online learning is beneficial for him:

I was accepted through the preparatory school to the Technion, so I also learned in the preparatory school during the pandemic, so I studied … .by myself, me and the computer … My basis is the preparatory school, … I got the grades I wanted. So like, in that situation, it was wow! I don’t know if it will work, I don’t know if it is really good for me … .But … I … saw that … I do reach a good level, and … I practiced 99 percent of the time alone.

I always watch at 2.5-2.75 (speed) … in all the courses I am like this. I don’t see 2.5 without stopping; I start to watch, try to understand, stop, sometimes also go back, see several times … The freedom that I can access every time and return to the same lesson or certain parts of the lesson … I can’t write and listen at the same time, it is very difficult for me.

Why would we sit ten people in the same class when everyone has their own different ideal pace, and we have to listen to the same lecturer at the same pace? I see no reason for it to happen … Before I get to the point where I can … practice with people, I first have to go through some kind of process with myself …

I would study with a friend who studied a different subject, but he also has the discipline, so we would sit together … and I am now also obligated to him, I mean, I can’t stop studying, because he is now studying too.

Students attending through different learning formats throughout the course (C2-S9, C2-S12, C4-S7, C5-S10). Level of understanding of the material was the main factor for interviewees C2-S9, C2-S12, C4-S7, and C5-S10. Interviewees C2-S9 and C4-S7 indicated the importance of arriving F2F when their level of understanding is low. C2-S9 participated F2F only when the lessons’ topic were not clear, whereas C4-S7 participated F2F only in courses that are not directly related to her major. C4-S7 says:

There are courses that I am much more focused on doing … then I will see a recording and I will understand more from it. Physics is not my field at all

The reason I didn’t come yesterday was that two days ago I was very stressed when I didn’t understand something, and I couldn’t both listen and try to understand what my gap was … At the same time I was here and I couldn’t concentrate, and I didn’t understand … from the whole situation and the pressure inside my head, I told myself that first I should finish my recordings, then I will go over the material and watch the lecture recording and I can pause when I need to solve the exercises, and I can repeat the explanations again, and I can be at my own pace, this is the advantage of recordings over F2F learning.

Discussion

Higher education institutions are currently trying to optimise course designs that will be more beneficial. Learning format is one factor in this vast scope. This research aimed to contribute to this quest by exploring students’ stated and revealed learning format preferences when provided the choice between three learning environments: synchronous F2F, synchronous online via Zoom, and asynchronous via lesson recordings. Furthermore, this study aimed to qualitatively examine students’ perceived benefits and pitfalls of the different learning formats before and after their learning experience. To achieve these goals, a teaching platform in physics higher education courses was developed and implemented to support the three learning formats students could choose from.

We found that students’ stated learning format preferences do not align entirely with their revealed preferences. While initially F2F alone was the most preferred learning format, consistent with other pre-COVID-19 studies (e.g. Barak et al., Citation2016; Jaggars, Citation2014), their actual attendance involved different combinations of F2F and online learning. Thus, students’ actual online attendance was much higher than their initial reported preferences. Nevertheless, most students still attended F2F while also utilising the online option, thus preferring a hybrid learning model. Students’ shifts between online and F2F learning are consistent with previous pre and post-COVID-19 studies’ findings (e.g. Castro & George, Citation2021; Gherheș et al., Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2013).

These shifts in attendance between different learning formats express students’ inner debate between the benefits and pitfalls of each learning format. Specifically, five main categories of benefits and pitfalls were found: Health, time/space flexibility, social learning, focus, and learning quality.

Health is a trivial benefit of online learning, allowing students to stay healthy during a pandemic. During this study, no governmental constraints existed on travelling and learning in class. However, there were times, mostly at the end of the fall semester of 2021, when there were high COVID-19 infection rates in the country, and mostly only at those times did students mention this benefit. While health considerations are mainly relevant in unique circumstances, COVID-19 has taught us that we should be prepared for such occasions.

Time and space flexibility were crucial factors in choosing online learning formats, as seen in students’ revealed preferences. Students who initially stated that they preferred at first to arrive F2F sometimes changed their attendance patterns to online formats due to time and/or space constraints. These factors were shown in pre-COVID-19 to be significant for students with work or family obligations, more common in graduate studies (e.g. Jaggars, Citation2014; Xu & Jaggars, Citation2014). Nevertheless, in this study, most of the participants were unemployed, indicating that time and space flexibility also benefit young students with no work or family obligations.

Social learning was only mentioned as a benefit of F2F learning, including social encounters and the ability to ask questions. While some students decided to arrive F2F because of the social encounter, there were also those who decided to learn online because they didn’t feel connected to their classmates. Even though those who attended Zoom could have asked questions during the lessons, they felt discomfort in asking questions.

Focus was a recurrent benefit of F2F learning and a pitfall of online learning prior to and following their learning experience. Students indicated that learning F2F created a better educational atmosphere than in their home environment, increasing their concentration and decreasing distractions. Moreover, attendance at class makes them more committed to learning. In contrast, focus was a recurrent pitfall of online formats. Students indicated that they must have high self-discipline to build and execute their own schedule in asynchronous lessons, yet they did not feel that they possessed such self-discipline. This was especially true for asynchronous learning, yet even synchronous online classes, which provide a specific time to learn, may challenge focus due to home environment distractions during the lesson. Lack of focus is often related to extensive phone use (i.e. social media, etc.) among students and has been found to be correlated to academic level (e.g. Albursan et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2015). Coming F2F may enrich the shared-attention state, i.e. a person’s psychological state when he is paying attention to an object while another individual is also watching it synchronously (Shteynberg, Citation2015). Research shows that people in a shared-attention state have more significant cognitive resources to the object (be the object a directive, behaviour, goal, etc.). It is expressed by better memory of the material (Shteynberg, Citation2010), stronger motivation to pursue goals (Shteynberg & Galinsky, Citation2011), and greater behavioural learning (Shteynberg & Apfelbaum, Citation2013). Nevertheless, some students were able to sustain focus in online settings through different techniques, such as learning individually in the same space with other learners or setting a learning atmosphere at home. In these cases, students preferred online over F2F learning.

Interestingly, time and space flexibility were not the only benefits of online learning. Learning quality was also a recurring benefit of online learning. In asynchronous learning, students can control the pace of the lesson. Secondly, regardless of students’ attendance, asynchronous learning enables reviewing the materials. The use of lesson recordings not only as a learning format to replace synchronous attendance but also as a tool for reviewing the material is in line with the study of Miller et al. (Citation2013). The study of Lavi et al. (Citation2021) indicated that individual learning was the primary twenty-first-century skill students developed during their studies, expressed mainly by reviewing the course material. Active learning is often considered a characteristic of F2F learning that enables class participation, whereas asynchronous learning is assumed to be more passive in nature (i.e. a student watching a video without participation) (Khan et al., Citation2017). Nevertheless, ‘activities that students do to construct knowledge and understanding’ can define active learning (Brame, Citation2016, p. 1). Controlling the pace of the lesson and reviewing the material are forms of active learning that are not possible in traditional teacher-centered F2F learning that is still commonly used in higher education.

The five main categories concerning the benefits and pitfalls of the learning formats (health, time/space flexibility, social learning, focus, and learning quality) can be understood through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) (Ryan & Deci, Citation2019). SDT identified three psychological needs for motivation and well-being, regardless of culture: competence (i.e. effective interaction with society), relatedness (i.e. sense of feeling belonging and cared about), and autonomy (i.e. the belief that one’s behaviour reflects ‘one’s own choice). In our study, focus and learning quality can be linked to competence, social learning to relatedness, and time/space flexibility and health to autonomy. Thus, learning models that provide multiple learning format choices may increase students’ motivation, which is the building block for executing and sustaining Self-Regulated Learning (SRL) behaviour (Willy & Maarten, Citation2012). SRL is a cyclic process of a student’s motivation and ability to set personal goals, build a learning strategy, apply it, and finally reflect on his learning process to improve until success (Zimmerman, Citation2002). Students should have high SRL skills to fully benefit from hybrid courses that allow them to learn with various learning formats (Bakach, Citation2021). While SRL is a very wide concept, our findings show that the perceived ability to focus influences students’ stated and revealed learning format choices. By providing strategies to increase focus, students may have more autonomy and competence to benefit from asynchronous online learning.

Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations to this study.

Firstly, generalisation is limited by: (1) sampling students who are learning only in a technological institution, (2) students having a strong motivation to participate in the course of the study (they were willing to pay to join the course), and (3) analysis is made only on the students who volunteer to answer the questionnaires. Courses in other fields and/or massive participants should be further examined.

Secondly, the study used a controlled research environment (i.e. provided precisely the same content through different learning formats). On the one hand, this method offers an opportunity to systematically compare between the three learning formats. On the other hand, it limits the optimal implementation of each learning format. For example, video lessons that are produced by lesson recordings may be less beneficial for asynchronous learning formats. Therefore, depending on the learning format, providing different pedagogical content may change students’ preferences.

Thirdly, in order to check students’ revealed learning format (RQ2), it was necessary to give them the freedom to choose their attendance. While some students decided to attend by all three learning formats, others have chosen to learn only by one or two. However, all students could write their opinions of the benefits and pitfalls of all the learning formats, but it is more limited if they had less experience in those formats during the course.

Lastly, the study did not check the impact of students’ learning format attendance on students’ performance but their subjective perception. To examine such causality, a randomised controlled study is required. Further research should also investigate whether teachers’ perspectives align with students’.

Conclusions

The initial motivation for distance education was to provide educational opportunities to those who cannot attend traditional F2F learning, due to family matters, financial constraints, living far from campus, and more. Nevertheless, online learning may entail pedagogical benefits over traditional F2F learning for all learners. This research shows that although the students were young, and almost all of them did not work for a living, many have decided to learn online. In addition, many students who attended synchronously also watched recordings to review the material. The realisation that online learning can benefit all learners can be connected to Universal Design, defined as the design of products and environments that can be used by all people to the possible greatest extent without adapting them or applying specialised design (Silver et al., Citation1998; Story et al., Citation1998). We believe that a good model should combine F2F and online learning to maximise the relative benefits of each learning format and minimise their pitfalls. Such a model can combine, for example, online asynchronous lectures with F2F tutoring and group sessions. However, for such a model to be effective, it is necessary to facilitate and promote students’ focus ability, the most commonly mentioned SRL skill perceived as a barrier to online learning in our study.

Ethical approval

The research was carried out in compliance with ethical standards. The study was approved by the Technion, and the participants signed a consent form before their participation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, A. E., Randall, S., & Traustadóttir, T. (2015). A tale of two sections: An experiment to compare the effectiveness of a hybrid versus a traditional lecture format in introductory microbiology. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 14(1), ar6.

- Albursan, I. S., Al. Qudah, M. F., Al-Barashdi, H. S., Bakhiet, S. F., Darandari, E., Al-Asqah, S. S., Hammad, H. I., Al-Khadher, M. M., Qara, S., & Al-Mutairy, S. H. (2022). Smartphone addiction among university students in light of the COVID-19 pandemic: Prevalence, relationship to academic procrastination, quality of life, gender and educational stage. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610439

- Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2017). Digital compass learning: Distance education enrollment report 2017. Babson Survey Research Group.

- Amiti, F. (2020). Synchronous and asynchronous E-learning. European Journal of Open Education and E-Learning Studies, 5(2), 60–70. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejoe.v5i2.3313

- Ariely, D., & Norton, M. I. (2008). How actions create – Not just reveal – Preferences. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(1), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2007.10.008

- Aristovnik, A., Keržič, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževič, N., & Umek, L. (2020). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability, 12(20), 8438. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208438

- Bakach, B. (2021). Investigating the HyFlex modality: Students’ satisfaction and impact on learning [PhD thesis].

- Bakia, M., Shear, L., Toyama, Y., & Lasseter, A. (2012). Understanding the implications of online learning for educational productivity. Office of Educational Technology, US Department of Education.

- Barak, M., Hussein-Farraj, R., & Dori, Y. J. (2016). On-campus or online: Examining self-regulation and cognitive transfer skills in different learning settings. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-016-0035-9

- Bećirović, S., & Dervić, M. (2023). Students’ perspectives of digital transformation of higher education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 89(2), e12243. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12243

- Ben-Akiva, M., & Morikawa, T. (1990). Estimation of switching models from revealed preferences and stated intentions. Transportation Research Part A: General, 24(6), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-2607(90)90037-7

- Berry, S. (2017). Educational outcomes of synchronous and asynchronous high school students: A quantitative causal-comparative study of online algebra 1 [PhD thesis, Northeastern University]. https://search.proquest.com/openview/9de3653d06b2e41244db80b44b58eb3c/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750.

- Besser, A., Flett, G. L., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2022). Adaptability to a sudden transition to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Understanding the challenges for students. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 8(2), 85. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000198

- Billington, P. J., & Fronmueller, M. P. (2013). MOOCs and the future of higher education. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 13(3/4), 36–43.

- Bozkurt, A. (2019). From distance education to open and distance learning: A holistic evaluation of history, definitions, and theories. In S. Sisman-Ugur & G. Kurubacak (Eds.), Handbook of research on learning in the age of transhumanism (pp. 252–273). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Brame, C. (2016). Active learning. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. https://www.oaa.osu.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/nfo/2019/Active-Learning-article.pdf.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Broadbent, J., & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review. The Internet and Higher Education, 27, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2015.04.007

- Cameron, M., Lacy, T. A., Siegel, P., Wu, J., Wilson, A., Johnson, R., Burns, R., & Wine, J. (2021). 2019-20 National postsecondary student aid study (NPSAS: 20): First look at the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on undergraduate student enrollment, housing, and finances (preliminary data). NCES 2021-456. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Castro, E., & George, J. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on student perceptions of education and engagement. E-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, 15(1), 28–39.

- Cavanaugh, J., & Jacquemin, S. J. (2015). A large sample comparison of grade based student learning outcomes in online vs. face-to-face courses. Online Learning, 19(2), 25–32. doi:10.24059/olj.v19i2.454

- Cho, M.-H., & Heron, M. L. (2015). Self-regulated learning: The role of motivation, emotion, and use of learning strategies in students’ learning experiences in a self-paced online mathematics course. Distance Education, 36(1), 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.1019963

- Council, N. R. (2012). Education for life and work: Developing transferable knowledge and skills in the 21st century. National Academies Press.

- del Arco, I., Silva, P., & Flores, O. (2021). University teaching in times of confinement: The light and shadows of compulsory online learning. Sustainability, 13(1), 375. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13010375

- Dennis, M. (2012). The impact of MOOCs on higher education. College and University, 88(2), 24.

- Duncan, K., Kenworthy, A., & McNamara, R. (2016). The effect of synchronous and asynchronous participation on students’ performance in online accounting courses. In Richard M. S. Wilson (Ed.), Researching accounting education (pp. 111–129). Routledge. https://api.taylorfrancis.com/content/chapters/edit/download?identifierName=doi&identifierValue=10.43249781315740140-7&type=chapterpdf.

- Duncan, O. D., & Duncan, B. (1955). A methodological analysis of segregation indexes. American Sociological Review, 20(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.2307/2088328

- Elliott, C., & Neal, D. (2016). Evaluating the use of lecture capture using a revealed preference approach. Active Learning in Higher Education, 17(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787416637463

- Fabriz, S., Mendzheritskaya, J., & Stehle, S. (2021). Impact of synchronous and asynchronous settings of online teaching and learning in higher education on students’ learning experience during COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 4544. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.733554

- Foddy, W., & Foddy, W. H. (1993). Constructing questions for interviews and questionnaires: Theory and practice in social research. Cambridge University Press.

- Gherheș, V., Stoian, C. E., Fărcașiu, M. A., & Stanici, M. (2021). E-learning vs. face-to-face learning: Analyzing students’ preferences and behaviors. Sustainability, 13(8), 4381. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084381

- Gonzalez, T., De La Rubia, M. A., Hincz, K. P., Comas-Lopez, M., Subirats, L., Fort, S., & Sacha, G. M. (2020). Influence of COVID-19 confinement on students’ performance in higher education. PLoS One, 15(10), e0239490.

- Greenhow, C., Graham, C. R., & Koehler, M. J. (2022). Foundations of online learning: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2090364

- Guppy, N., Verpoorten, D., Boud, D., Lin, L., Tai, J., & Bartolic, S. (2022). The post-COVID-19 future of digital learning in higher education: Views from educators, students, and other professionals in six countries. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(6), 1750–1765. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13212

- Haningsih, S., & Rohmi, P. (2022). The pattern of hybrid learning to maintain learning effectiveness at the higher education level post-COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Educational Research, 11(1), 243–257.

- Holzer, J., Lüftenegger, M., Korlat, S., Pelikan, E., Salmela-Aro, K., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2021). Higher education in times of COVID-19: University students’ basic need satisfaction, self-regulated learning, and well-being. AERA Open, 7, 23328584211003164. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584211003164

- Iesalc, U. (2020). COVID-19 and higher education: Today and tomorrow. Impact analysis, policy responses and recommendations. UNESCO Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/covid-19-en-090420-2.pdf.

- Iglesias-Pradas, S., Hernández-García, Á, Chaparro-Peláez, J., & Prieto, J. L. (2021). Emergency remote teaching and students’ academic performance in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106713

- Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Choosing between online and face-to-face courses: Community college student voices. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(1), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.867697

- Kara, M., Erdogdu, F., Kokoç, M., & Cagiltay, K. (2019). Challenges faced by adult learners in online distance education: A literature review. Open Praxis, 11(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.929

- Kentnor, H. E. (2015). Distance education and the evolution of online learning in the United States. Curriculum and Teaching Dialogue, 17(1), 21–34.

- Khan, A., Egbue, O., Palkie, B., & Madden, J. (2017). Active learning: Engaging students to maximize learning in an online course. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 15(2), 107–115.

- Kizilcec, R. F., Pérez-Sanagustín, M., & Maldonado, J. J. (2017). Self-regulated learning strategies predict learner behavior and goal attainment in Massive Open Online Courses. Computers & Education, 104, 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.10.001

- Lavi, R., Tal, M., & Dori, Y. J. (2021). Perceptions of STEM alumni and students on developing 21st century skills through methods of teaching and learning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101002

- Lee, J., Cho, B., Kim, Y., & Noh, J. (2015). Smartphone addiction in university students and its implication for learning. In G. Chen, V. Kumar, Kinshuk, R. Huang, & S. C. Kong (Eds.), Emerging issues in smart learning (pp. 297–305). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Libasin, Z., Azudin, A. R., Idris, N. A., Rahman, M. A., & Umar, N. (2021). Comparison of students’ academic performance in mathematics course with synchronous and asynchronous online learning environments during COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 10(2), 492–501. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARPED/v10-i2/10131

- Luo, Y., Lin, J., & Yang, Y. (2021). Students’ motivation and continued intention with online self-regulated learning: A self-determination theory perspective. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 24(6), 1379–1399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-021-01042-3

- Mayring, P. (2004). Qualitative content analysis. A Companion to Qualitative Research, 1(2), 159–176.

- Means, B., Toyama, Y., Murphy, R., Bakia, M., & Jones, K. (2009). Evaluation of evidence-based practices in online learning: A meta-analysis and review of online learning studies.

- Melgaard, J., Monir, R., Lasrado, L. A., & Fagerstrøm, A. (2022). Academic procrastination and online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Procedia Computer Science, 196, 117–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2021.11.080

- Miller, J., Risser, M., & Griffiths, R. (2013). Student choice, instructor flexibility: Moving beyond the blended instructional model. Issues and Trends in Educational Technology, 57(1), 8–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-013-0654-0

- Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). e-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education, 14(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.10.001

- Moores, E., Birdi, G. K., & Higson, H. E. (2019). Determinants of university students’ attendance. Educational Research, 61(4), 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2019.1660587

- NCES. (2021). Student Enrollment—What is the percent of students enrolled in distance education courses in postsecondary institutions in the fall? https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds/TrendGenerator/app/answer/2/42?rid=5&cid=57.

- NCES. (2022). The NCES Fast Facts Tool provides quick answers to many education questions (National Center for Education Statistics). National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=80.

- Nieuwoudt, J. E. (2020). Investigating synchronous and asynchronous class attendance as predictors of academic success in online education. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.5137

- Nortvig, A.-M., Petersen, A. K., & Balle, S. H. (2018). A literature review of the factors influencing e-learning and blended learning in relation to learning outcome, student satisfaction and engagement. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 16(1), 46–55.

- Papadakis, S. (2023). MOOCs 2012-2022: An overview. Advances in Mobile Learning Educational Research, 3(1), 682–693. https://doi.org/10.25082/AMLER.2023.01.017

- Pappano, L. (2012). The year of the MOOC. The New York Times, 2(12), 2012.

- Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications.

- Philipps, C. (1728). Caleb Philipps teacher of the new method of short hand. The Boston Gazette, 436(2).

- Pittman, V. V. (2003). Correspondence study in the American university: A second historiographic perspective. In M. G. Moore & W. G. Anderson (Eds.), Handbook of Distance Education (pp. 21–35).

- Powers, K. L., Brooks, P. J., Galazyn, M., & Donnelly, S. (2016). Testing the efficacy of MyPsychLab to replace traditional instruction in a hybrid course. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 15(1), 6–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725716636514

- Price Banks, D., & Vergez, S. M. (2022). Online and In-person learning preferences during the COVID-19 pandemic among students attending the City University of New York. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 23(1), e00012–22. doi:10.1128/jmbe.00012-22

- Qayyum, A., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018). Open and distance education in Australia, Europe and the Americas: National perspectives in a digital age. Springer Nature.

- Ramos-Morcillo, A. J., Leal-Costa, C., Moral-García, J. E., & Ruzafa-Martínez, M. (2020). Experiences of nursing students during the abrupt change from face-to-face to e-learning education during the first month of confinement due to COVID-19 in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155519

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2019). Brick by brick: The origins, development, and future of self-determination theory. In Andrew J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 6, pp. 111–156). Elsevier.

- Samuelson, P. A. (1948). Consumption theory in terms of revealed preference. Economica, 15(60), 243–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2549561

- Saykili, A. (2018). Distance education: Definitions, generations, key concepts and future directions. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 5(1), 2–17.

- Serhan, D. (2020). Transitioning from face-to-face to remote learning: Students’ attitudes and perceptions of using zoom during COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Technology in Education and Science, 4(4), 335–342. https://doi.org/10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.148

- Shah, D. (2019, December 3). By The Numbers: MOOCs in 2019. The Report by Class Central. https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-stats-2019/.

- Shah, D. (2021, December 1). By The Numbers: MOOCs in 2021. The Report by Class Central. https://www.classcentral.com/report/mooc-stats-2021/.

- Shen, D., Cho, M.-H., Tsai, C.-L., & Marra, R. (2013). Unpacking online learning experiences: Online learning self-efficacy and learning satisfaction. The Internet and Higher Education, 19, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.04.001

- Sherry, L. (1995). Issues in distance learning. International Journal of Educational Telecommunications, 1(4), 337–365.

- Shteynberg, G. (2010). A silent emergence of culture: The social tuning effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(4), 683. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019573

- Shteynberg, G. (2015). Shared attention. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615589104

- Shteynberg, G., & Apfelbaum, E. P. (2013). The power of shared experience: Simultaneous observation with similar others facilitates social learning. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(6), 738–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613479807

- Shteynberg, G., & Galinsky, A. D. (2011). Implicit coordination: Sharing goals with similar others intensifies goal pursuit. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(6), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.04.012

- Silver, P., Bourke, A., & Strehorn, K. C. (1998). Universal Instructional Design in higher education: An approach for inclusion. Equity & Excellence in Education, 31(2), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066568980310206

- Stern, B. S. (2004). A comparison of online and face-to-face instruction in an undergraduate foundations of American education course. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 4(2), 196–213.

- Story, M. F., Mueller, J. L., & Mace, R. L. (1998). The universal design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities.

- Traphagan, T., Kucsera, J. V., & Kishi, K. (2010). Impact of class lecture webcasting on attendance and learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(1), 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-009-9128-7

- Uekusa, S. (2023). Reflections on post-pandemic university teaching, the corresponding digitalisation of education and the lecture attendance crisis. New Zealand Geographer, 79(1), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/nzg.12351

- UN. (2020). UNSDG | Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond.

- Wang, C.-H., Shannon, D. M., & Ross, M. E. (2013). Students’ characteristics, self-regulated learning, technology self-efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning. Distance Education, 34(3), 302–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2013.835779

- Willy, L., & Maarten, V. (2012). Promoting self-regulated learning: A motivational analysis. In Dale H. Schunk & Barry J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning (pp. 141–168). Routledge.

- Wolters, C. A. (2010). Self-regulated learning and the 21st century competencies. Department of Educational Psychology, University of Houston.

- Xu, D., & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face-to-face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas. The Journal of Higher Education, 85(5), 633–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2014.11777343

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2