Abstract

This article examines the dynamics of heritage language (HL) identity development by analysing the life history accounts of three Chinese heritage language (CHL) learners growing up in the UK. Drawing on narrative data, the study contributes to the growing body of HL identity research by capturing the individual trajectories of CHL learners engaging with different interlocutors, at multiple sites, and across the lifespan. We report the various ways our participants are positioned by the essentialist discourses of Chineseness and how they learn to (re)position themselves as competent HL learners and legitimate members of the diasporic community. The findings highlight the need to understand HL learners’ identity and agency as emergent from varied social interactions embedded within one’s personal history. In light of the findings, we propose an original model to theorise the dynamics of HL identity development from a historical, spatial, and relational lens, and conclude with practical suggestions to encourage HL learning and maintenance.

Introduction

A global rise in transnational mobility has led to increasing numbers of immigrant minorities in Anglophone countries, and there are widespread concerns about the loss of heritage languages (HLs) and identities among their second-generation children (He Citation2006; Leeman Citation2015). In this context, recent studies have started to explore issues of individuals’ HL development in relation to their sense of self (e.g. Abdi Citation2011; Blackledge et al. Citation2008; Creese et al. Citation2006; Kang Citation2013; Showstack Citation2012, Citation2017). These studies have often focused on how learners’ identities are constructed, performed, and negotiated within HL classroom settings. Notably absent from these studies are the dynamics of HL identity development beyond HL classrooms in a range of sites such as home, school, community, and workplace, across one’s lifespan. This article adds to such studies by capturing the personal historicity in the construction and reproduction of self across multiple sites — as ‘children’ within the family, ‘students’ inside the school, ‘members’ of the Chinese community, and ‘employees’ in the workplace. This lifespan perspective, we argue, is central to our understanding of the dynamic nature of identity construction, particularly among HL learners. It also offers valuable insights which complement the existing literature on bilinguals’ experience of language acquisition across the lifespan.

The study examines the dynamics of HL identity development among three Chinese heritage language (CHL) learners by analysing their life narratives. It explores how CHL learners are positioned by two essentialist discourses of Chineseness, namely the model minority discourse and the moral discourse on authenticity, and how they exercise agency to resist that positioning and attempt re-positioning in varied social interactions. By examining the various ways of how CHL learners position themselves and are positioned by others across time and space, this article enhances our understanding of the complex interplay between power and agency in HL identity formation. It further contributes to theorisation of the dynamics of HL identity development, which is generally overlooked in previous research, from a historical, spatial, and relational lens.

Identity in heritage language development

Identity has been long regarded as a key aspect of HL development and has received increasing scholarly attention in the past decades (Leeman Citation2015; Tseng Citation2020). While earlier survey-based research tends to conceive heritage learners’ identity as a fixed category (e.g. Beaudrie, Ducar, and Relaño-Pastor Citation2009; Comanaru and Noels Citation2009; Kiang Citation2008), recent HL studies mainly draw on poststructuralist frameworks and allow for a less essentialised understanding of identities (e.g. Doerr and Lee Citation2013; Kim Citation2020; Wong and Xiao Citation2010). Instead of conceptualising heritage learners’ identity as static or pre-determined, many of these studies have demonstrated the dynamics of identity development and examined HL identities as discursively or narratively constructed (Gyogi Citation2020; Jing-Schmidt, Chen, and Zhang Citation2016; Park Citation2021). We adopt this poststructuralist view as a starting point for theorising HL identities in this study, because it enables us to avoid an oversimplification of HL learners’ developmental trajectories and to see how their multiple identities, on the one hand, structure access to linguistic resources and learning opportunities and, on the other hand, are performed, negotiated, and redefined vis- à-vis HL practices.

The dynamics of HL identity development first lies in the conceptualisation of identities as complex, fluid, and socially constructed across time and space (Norton Citation2000; Pavlenko and Blackledge Citation2004). As HL learners grow and become more mentally mature, they construct their identities in a dynamic process influenced by family, school, community, and beyond (Tseng Citation2020). This also refers to the relational aspects of identities that learners may experience when interacting with different interlocutors from one site to another (Taylor Citation2014). Although a growing number of studies have recognised this dynamic nature of HL identity (e.g. Kang Citation2013; Park Citation2021), they focus more on the immediate aspects of how learners position themselves in the present, rather than why that present has come to exist from one’s long social history. Further studies, therefore, need to examine HL identities by looking at the rich individual trajectories of interaction with various fields, interlocutors, and life events. In this study, we adopt the notions of ‘historicity’ and ‘spatiality’ to describe the dynamics of HL identity in flow (Hirsch and Stewart Citation2005); that is, how learners’ identities come into being temporally and spatially in their varied social interactions across a lifespan.

The process of HL identity development is also inevitably related to the concept of power. As previous research has indicated, languages and identities are embedded within powerful discourses, which may be contested, negotiated, or found to be non-negotiable (Bourdieu Citation1991; Norton and Toohey Citation2011; Pavlenko and Blackledge Citation2004). For HL learners, their language learning and maintenance are not only constrained by the dominant discourses that favour English in the wider society (Lee and Wright Citation2014), but also susceptible to the internal hegemonic pressure derived from the essentialisation of ethnicity and heritage within diasporic communities (Creese et al. Citation2006; Showstack Citation2012). This pressure prevalent in immigrant minority groups is always reproduced within HL schools, internalised by children and their parents, and as a result, leads to forced-positioning of HL learners as ‘linguistically deficient and culturally inauthentic’ (Helmer, 2011, 2013; Tseng Citation2020, p. 131). In a study of US-born Latinos, for example, Tseng (Citation2021) shows how this imposed deficit positioning stigmatises HL learners, damages their identities and self-esteem, and contributes to HL insecurity and avoidance. Similarly, while a stronger identification with Chineseness generally motivates CHL maintenance (He Citation2006; Mu Citation2014), in our research, these beliefs embedded within the essentialist discourses also constrain learners’ identity options and negatively affect their participation in CHL learning and use. In such a case, when CHL learners are positioned deficiently, they tend to avoid speaking Chinese despite positive attitudes towards the language.

However, HL learners are not simply passive recipients of the imposed positioning; they can also exercise their agency to negotiate identities, attempt re-positioning, and deploy discourses and counter-discourses to contest those in power (Blackledge et al. Citation2008; Doerr and Lee Citation2009; Duff Citation2013). The concept of agency is increasingly understood as the ‘socioculturally mediated capacity to act’ (Ahearn Citation2010, p. 28) rather than an internal state that resides within the individual (Bucholtz and Hall Citation2005). With regard to HL learning, a few recent studies have explored how HL learners, as active social agents, negotiate their identities within hegemonic discourses (Blackledge et al. Citation2008; Koshiba Citation2020; Showstack Citation2012). For example, in a study of Hispanic bilinguals in the US, Showstack (Citation2012) shows how HL students challenged a prevailing classroom discourse based on a ‘monoglossic language ideology’ (García Citation2009) and defended their identities as legitimate Spanish speakers. Another example can be seen in Blackledge et al.’ (2008) study conducted in Bengali complementary schools in the UK. Their data show that, despite the powerful discourses that framed the teaching of ‘language’ as the teaching of ‘heritage’, students were often seen to contest the imposed heritage identities through classroom interaction. However, research that highlights the role of HL learners’ agency is still relatively rare and most of these studies solely focus on HL classroom settings. As Miller (Citation2010, Citation2012) suggests, human agency is also discursively and historically mediated. Drawing on the notion of ‘history in person’ (Holland et al. Citation1998), she notes that individuals’ agentive capacity is not uniformly shaped but comes from ‘the sediment from past experiences’ of one’s long social histories (as cited in Miller Citation2012, p. 444). Therefore, we aim to extend this line of enquiry by exploring the socially formed histories of CHL learners in which their agency and identities develop. We will show their negotiation of the essentialist discourses of Chineseness when growing up in the UK and how that process leads to HL learning opportunities as well as possibilities for identity transformation.

Informed by the above discussion, we argue for a need to understand the dynamics of HL identity development by exploring the life histories of HL learners engaging with different interlocutors, at multiple sites, and across the lifespan. We consider their life histories not to be determined, but as the consequence of the negotiations of power and agency. By examining the various ways of how CHL learners position themselves and are positioned by others across time and space, we will come to see their distinct trajectories of identity construction and HL development. Before delving into the current narrative study, we now turn to the essentialist discourses in which CHL learners’ life histories are situated.

Essentialist discourses of Chineseness

Bucholtz and Hall (Citation2004) define essentialisation as an assumption that all members of a given identity category share certain attributes which define who they are. In Chinese diasporic communities, the essentialist Chineseness discourses conflate the notions of language, ethnicity, and culture, and refer to Chinese as an idealised and homogeneous group (Francis, Archer, and Mau Citation2009). This essentialist representation of Chineseness does not just come from external forces but also from within the Chinese community itself (Hoon Citation2021). As we will show, while the increasingly heterogeneous landscapes of the British Chinese community seem to provide limitless identity options for CHL learners, people are still categorised under the umbrella term of ‘British Chinese’ and are confined by the hegemonic discourses on what Chinese people should or should not be like. For the purpose of this study, we focus on two essentialist Chineseness discourses that are salient in the British Chinese community — the model minority discourse and the moral discourse on authenticity.

The model minority discourse, emerging in the late 1960s in the United States, is used to acknowledge the educational/career success of Asian Americans and to portray them as a hard-working, disciplined, and problem-free minority group (Ng, Lee, and Pak Citation2007). This public portrayal, as Archer and Francis (Citation2005) claim, can also be observed in the British context, frequently cited as the reason for their high academic achievement and attained upward social mobility. In fact, this imposed identity permeates well into many British Chinese’s own senses of ethnic pride (Mau Citation2013). Mau’s (Citation2013) study showed that many parents and children have indeed accepted, or even enthusiastically embraced, the model minority discourse, and as a result, they place immense emphasis on academic performance at school. The model minority stereotype further implies that, in order to succeed in mainstream schooling, minority groups tend to conform to the norms of the dominant culture at the expense of their own heritage language and culture (Kang Citation2015). Therefore, it homogenises the experience of many British Chinese and affects their perceptions of themselves, the value they attach to the HL, and their educational choices.

By moral discourse on authenticity, we refer to a type of discourse that equates language proficiency to one’s ethnic duty and emphasises the ‘authenticity and moral significance’ of the so-called mother tongue of a given heritage (Woolard Citation1998, p. 18). It prescribes that those who are tied to a given ethnic membership should be naturally able to speak that corresponding language fluently, as a way to fulfil his/her moral obligation and perform being authentically (Abdi Citation2011; Mau Citation2013). This discourse norm of possessing an authentic identity is integrally bound up with the monolingual native speaker ideology, which requires HL learners to reach an idealised native standard and positions those who fail to do so as ‘deficiently native speakers’ (Train Citation2007, p. 229). Thus, it fails to capture the unique linguistic competence of HL learners through inappropriate comparison with their monolingual counterparts despite their different learning contexts (Rothman and Cabo Citation2012).

However, the essentialist representations of being a model minority and speaking authentic Chinese have long been regarded as positive attributes both by mainstream UK society and by British Chinese themselves (Archer and Francis Citation2005). As such, their hidden risks have always failed to be recognised. This requires a closer look at how these hegemonic discourses constrain learners’ identity options and negatively affect their HL development. In this paper, we explore how the essentialist discourses of Chineseness structure the identity construction of our participants, and how they are contested, negotiated, and reproduced vis- à-vis HL practices. By looking at this complex interplay of power and agency, we will come to see the dynamics of HL identity development, as represented in the rich individual life histories.

The study

We adopt narrative inquiry as a methodology in this study. Narratives offer a way to bring coherence to learners’ multiple and shifting identities, and thus are particularly well suited to the study of HL identities from a relational, spatial, and historical perspective (Barkhuizen, Benson, and Chik Citation2013; Benson Citation2013; Pavlenko Citation2007). As Wortham (Citation2001) suggests, narratives are powerful media through which individuals express, enact, and make sense of their selves. Indeed, the social world is constituted by ‘story constellations’ (Craig Citation2007, p. 173) and human beings experience their lives and identities in narrative form (Polkinghorne Citation1988). Thus, documenting humans’ experience involves a process of restorying – ‘the living, telling, retelling, and reliving of our stories’ (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000, p. 387). CHL learner’s life history accounts, in this sense, not only show how a person constructs dynamic identities through specific narrative resources, but also facilitate a form of agency and resistance to normative identities while giving birth to different narratives of the self (Coffey and Street Citation2008).

The participants of this study are John, Ryan, and Lucy (pseudonyms, aged 29, 22, and 18 respectively at the time of the study), three adult CHL learners in the UK. Hornberger and Wang (Citation2017) define HL learners as ‘individuals with familial or ancestral ties to a language other than English who exert their agency in determining if they are HLLs of that language’ (p. 6). We adopt it as our working definition in this study, because it acknowledges learners’ agentive role in constructing their identities and the heterogeneity within the group. The three participants were recruited through poster invitations placed in a local Chinese community centre where Chinese immigrants and their children living in surrounding areas meet and socialise. They were selected mainly for two reasons. Firstly, they all fit well with Hornberger and Wang (Citation2017) definition of HL learners. They were children of Chinese immigrants, born in the UK, and grew up speaking both Chinese and English. All participants felt comfortable with their HL learner identity and actively learned/used Chinese at the time of the study. Secondly, despite the commonality, the three participants also showed different life trajectories of identity and HL development. The range of their experience and how they constructed their experience in their life histories provided us with richly diverse narrative data.

The data were collected from a series of three interviews conducted with each participant following Seidman’s (Citation2006) life history interview model. Each interview lasted around 60 to 90 minutes, with a clear focus and purpose that differed from the other two (Seidman Citation2006). The first round of interviews was intended to elicit an overall account of the participants’ life history. It was guided by an interview protocol that helped participants to re-arrange the events of their lives in a chronological order based on where they had taken place (e.g. home, school, community, workplace). Questions for the second and third interviews were derived from the themes emerging from the first interview. During the interviews, initial interpretations of the participants’ remarks were provided, and the participants were asked to confirm, revise, or reject these interpretations. This process improved the trustworthiness of the data and always invited new stories from the participants.

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed in three phases. The first phase employed an approach called ‘narrative writing’ (Benson Citation2014, p. 11), by which we turned data with a rudimentary narrative structure into formal written narratives that follow a chronological order. Each narrative case was then thematically analysed with the software NVivo based on an inductive coding process where categories and themes were not predetermined but emerged (Marshall and Rossman Citation2014). This process involved coding the data line by line and grouping the codes together to create categories and subsequent themes. After multiple rounds of coding, several broader themes were identified for retelling the stories (Clandinin and Connelly Citation2000), such as ‘dominant discourses’, ‘response to discourses’, ‘(non)participation’, ‘personal transformation’, and so on. The final stage consisted of a cross-case synthesis that enabled us to look more closely at how the themes connected or diverged among the narratives. This three-phase analysis allowed us to capture three distinct trajectories of HL identity development on the one hand, and the similarities of the negotiations, resistance, and personal transformations on the other. In the findings section below, we present the narratives of HL identity construction of the participants engaging with different interlocutors, at various sites, and across the lifespan.

Findings

John: from ‘struggling’ to ‘self-motivating’

Struggling to become a model minority

John was born in the UK with both his parents working in a family catering business. The family’s financial hardship after immigration made his parents enthusiastically embrace the prominent model minority discourse, viewing it as a strategy to escape current working-class status and to realise upward social mobility in British society. John recalled how strict his parents were when he was younger: ‘they kept telling [me] to work hard and wanted me to be academically strong’ (John, first interview). He also recalled that, despite the financial hardship, his parents ‘worked hard to send me to a private school… and always said they spent every penny on my school fees’ (John, first interview).

Influenced by the ascribed positioning as a model minority, John’s struggle to fit this expectation had become a recurrent theme in his childhood stories. Contrary to his parents’ expectation — a hard-working, compliant, and academically inclined student, he described himself as ‘rebellious,’ ‘naughty,’ and ‘not really good at studying.’ Such imposed positioning further made him feel that he did not live up to ‘being a typical Chinese,’ who, unlike him, fits the high achieving narrative.

The model minority stereotype not only stigmatises people who fail to succeed in mainstream schooling, but also has real effects on how British Chinese perceive the value attached to their HL. Since the learning and maintenance of Chinese did not directly contribute to John’s academic achievement at school, he was always told to ‘focus on schoolwork’ at the expense of his CHL development. Unlike many Chinese parents, John’s did not send him to the Chinese complementary school to learn Chinese literacy, because it was ‘quite expensive’ and ‘they could teach [me] themselves’ (John, first interview). However, in reality, John’s parents gave up his HL literacy development at an early age:

They stop trying to teach me to write, because it’s getting more and more difficult… as long as I’m able to communicate, they’re fine about that. (John, first interview)

Self-motivating to be a competent CHL learner

While the moral discourse on authenticity did not have a strong presence in the first half of John’s story, it then came into play when he took up a position in a Chinese supermarket at the age of 25. There, Chinese was not only a marker of ethnicity, but also a language that allowed him to perform professional duties. Because of this, as John’s workplace stories unfolded, we could see his self-motivating trajectory of re-acquiring CHL and becoming a legitimate CHL learner, which coincided with the trajectory of becoming a competent co-worker.

When he first started his job, John was particularly worried about his imperfect mastery of Chinese. He was afraid of being viewed as a less competent co-worker and felt ‘embarrassed’ and ‘stressed’ from time to time. John’s feeling of incompetence at work, indeed, arose from the tension between people’s essentialist assumption toward him as a Chinese and his own inability to speak the perfect Chinese language. This tension further placed him in a dilemma — on the one hand, he needed to speak more Chinese with his customers and co-workers to improve his fluency; on the other hand, the potential embarrassment of exposing his inauthenticity, especially in front of those native Chinese, discouraged him from doing so. John recalled a short period of time when he chose to keep quiet at work. However, he gradually realised that this strategy was again ‘very embarrassing,’ because it would make people feel that ‘[he does not] know how to speak Chinese at all’ (John, first interview). In this sense, keeping quiet would only reduce his credence as a competent employee in the eyes of his boss and co-workers.

As an agentive young man, John seemed determined to improve his CHL proficiency and attempted to negotiate his positioning by mobilising his bilingual resources. For example, he mentioned playing an active role with English-speaking customers or when there was a need to translate some product descriptions. Gradually, his co-workers began to refer to him as an English expert, often asking him questions concerning English. In this way, his bilingual resources became a bonus which was valued in the workplace, serving to offset his imperfect Chinese:

… [I don’t feel myself as] less competent… because you can help each other learn, like I sort of ask them what this product means in Chinese, and just trying to remember for the next time; and if they don’t understand the English word for some items… So it’s like I can help them with their English, and they can help me with my Chinese. (John, third interview)

Compared with how he was constrained by the model minority discourse in his early life, John gradually learned to negotiate positioning when he grew older. We also see that he adopted a ‘thought-reframing’ strategy to generate an inner counter-discourse (Cervatiuc Citation2009, p. 259) as a way to contest the essentialist Chineseness. Instead of comparing with an idealised native speaker standard, John felt increasingly able to accept his inability to speak perfect Chinese and made the point that ‘it’s quite reasonable and fair to have accent’ (John, third interview) as a CHL learner born and raised in the UK. This further increased his self-confidence and motivated him to make progress in learning the HL.

In sum, John’s life history account shows a trajectory from struggling to self-motivating: he struggled to conform to the model minority discourse at the expense of his CHL development at the early stage of his life; however, as he grew and became more mature, he was self-motivated to re-acquire Chinese, re-position himself as a legitimate CHL learner, and at the same time, gain the credence as a competent co-worker in the workplace.

Ryan: from ‘embracing’ to ‘challenging’

Embracing the moral discourse of being an authentic Chinese

Unlike John, Ryan was born in a family where the Chinese language and culture were highly valued. Having traditional parents who had a strong desire to maintain and pass on their Chinese traditions, Ryan was required to learn Chinese from an early age. He was sent to a Chinese complementary school every Sunday morning from 6 to 13 and took GCSE Mandarin afterwards. As the participant with the highest CHL proficiency, Ryan also displayed the strongest sense of connection with his Chinese heritage. His essentialist attitude towards being an authentic Chinese gradually emerges in the first half of his narrative.

When Ryan was about 12, his parents became regular members of a local Chinese community centre and started to bring him there at weekends. Here, he started to make friends with other British Chinese pupils who shared similar background. Gradually, the community centre became an important social site for Ryan, and because of this, it motivated him to go there regularly to meet his Chinese friends. Apart from that, he was also actively involved in some Chinese cultural events held by the centre. In the following excerpt, Ryan talked about his experience of performing Lion Dance, a form of traditional Chinese dance, when he was 14. It should be noted, by performing Chineseness, Ryan further developed a strong sense of belonging to his familial origin, which can be seen from his use of the term ‘our culture’ when referring to the Chinese culture:

… I’ve been to the Dragon Boat Festival thing, and we performed there. It’s fun to celebrate our culture everywhere… people seem to enjoy it, even a lot of British people. (Ryan, third interview)

I know a lot of people there who are a little bit younger than me… What I find is a lot of them can’t speak Chinese, and it’s really a shame… It’s important to know Chinese if you’re Chinese, because then you can say you are Chinese, but what’s the point if you say you are Chinese, but you can’t speak the language, if you can’t talk to Chinese people. (Ryan, second interview)

From being authentic Chinese to being British Chinese

A turning point in Ryan’s life history came when he started to socialise with a group of Chinese international students at university. These interactions with native Chinese provided him with exposure to different ways of being, speaking, and living as an authentic Chinese, which enabled him to have a new understanding of his identity as a British Chinese and a CHL speaker.

Ryan described his feeling of being ‘less Chinese’ when talking to those international students from China. With a different way of speaking, such as not using ‘lah’ or ‘leh’ (i.e. discourse particles commonly used by ethnic Chinese), Ryan considered himself to be different from them. He also recalled that he sometimes could not fully express his ideas in Chinese and needed to code-switch to English from time to time. This inability to engage in conversation solely in Chinese made him ‘feel ashamed’ in front of his Chinese friends; in other words, he felt deficient as a CHL learner compared with those idealised native speakers.

Being positioned deficiently by the essentialist discourse on authenticity, John tended to avoid socialising with Chinese international students and making progress in his HL. Compared with his behaviour in the Chinese community centre — actively socialising with Chinese people and participating in various cultural events — Ryan seemed to have less interest in maintaining friendship with Chinese international students and even avoided opportunities to practise Chinese with them. When explaining this different attitude towards Chinese, Ryan said:

… before, when I was talking about Chinese… I mean in the community centre, I guess I mean British Chinese. I’m just much closer with British Chinese people, those BBCs [British-Born-Chinese]. (Ryan, third interview)

At almost the end of the third interview, Ryan was asked again about his identities. This time, he started to reflect upon his personal historicity and reconstruct hybridised identities:

I can’t say I’m completely Chinese… or British, because I no longer think in a way that “oh, this a Chinese thing, and this is an English thing,” I just have my own set of values, which is derived from both English and Chinese. (Ryan, third interview)

Lucy: from being ‘disempowered’ to ‘empowered’

Being disempowered by the essentialist discourses

Lucy was born in the UK and went to a school where she was the only Asian student in her class. There, the essentialist model minority discourse had a strong presence in her life. When talking about the stereotypes that depict ethnic Chinese as academically strong, she used words such as ‘annoying,’ ‘degrading,’ and ‘hurtful’ to describe her feelings. She further explained that, if being successful in school was essentialised as an inherent Chinese ability, then an individual’s achievements would simply be regarded as a result of his/her ethnicity. This downplayed her as an individual and made her ‘feel like a useless person’ (Lucy, first interview).

Apart from it, the powerful moral discourses that equate Chinese proficiency to ethnic duty also placed Lucy in a powerless position at school. She recalled a time when her teachers put her in charge of a group of newly-arrived Chinese boarders, because they assumed that she had no problem in speaking Chinese. It should be noted that, even if she found this request ‘strange’ and even ‘scary’ at that time, she did try to make friends with these international students, as she explained, ‘since I’m technically Chinese, I feel kind of obligated that I should be able to speak Chinese… and to speak more to the borders’ (Lucy, second interview).

Similar to John and Ryan, being positioned negatively by the essentialist discourse on authenticity, Lucy recounted a sense of embarrassment, sometimes possibly deficiency and shame, when speaking Chinese in front of those native speakers. Also similar to John and Ryan, being aware of her ‘improper and accented Chinese’ did not push Lucy to practise more. Instead, she reported being reluctant to use Chinese when her legitimacy of CHL speaker failed to be recognised:

It’s quite stressful for me because I feel like I can’t say anything properly. It’s also because I don’t sound that authentic, as people who were born in Hong Kong, so even if I do speak Chinese, they will definitely notice my accent. (Lucy, second interview)

Feeling empowered by a Chinese heritage

A turning point in Lucy’s life came when she started to volunteer at the Chinese community centre every Sunday at the age of 16. Initially, she just went there to complete the volunteering hours required by school. However, it then became a transformative experience for her. Retelling the story, we could see how Lucy, as an agentive young woman, actively negotiated her positioning and empowered herself.

Lucy’s main responsibility in the community centre was to organise a language corner, where she and her British Chinese peers could help some newly-arrived Chinese immigrants with their English. Unlike her previous experience with those Chinese boarders who made her ‘feel embarrassed’ as a deficient Chinese speaker, Lucy said that she ‘felt more comfortable’ staying with native Chinese this time. By mobilising her bilingual resources, Lucy was able to reposition herself as an English expert:

We kind of help some people who want to learn English, like some conversational English… It was also beneficial for us because it makes us feel valued… it also helps me get a bit more confidence. (Lucy, second interview)

They’ve been helping me, and they’ve been encouraging me to speak more and to learn more because I can learn more by speaking actually. And I’m also helping them with their English in a way. So, I think it’s a good exchange. (Lucy, second interview)

Having a group of British Chinese friends further offered Lucy an opportunity to open up a ‘third space’ (Bhabha Citation1994). Just as in Ryan’s case above, this third space served as a comfortable site where Lucy and her friends could share their similar experience growing up in the UK, reclaim the Chinese part of themselves, and make sense of their legitimacy as CHL learners.

To conclude, Lucy’s story presents a trajectory from disempowering to empowering: rather than trying to hide her Chinese heritage, Lucy now feels that it is a source of strength and self-affirmation. Learning and maintaining CHL is no longer a moral obligation but what she truly wants to do, as is shown in this final remark:

Now I kind of feel like it’s kind of… not obligation, but I feel more responsible to actually do something with it. So I know that I have a power… Instead of just saying that I was born here but I’m not really Chinese, I can actually say that I was born here and I’m also like… I can speak Chinese and still have connections to my Chinese sides. (Lucy, third interview)

Discussion

This study draws on data collected from three CHL learners’ life histories to explore the dynamics of HL identity development. It has demonstrated how the participants negotiated the essentialist discourses of Chineseness and learned to (re)position themselves as competent HL learners and as legitimate members of the diasporic community. By studying CHL learners’ interaction with different interlocutors at various sites across the lifespan, the findings highlight the dynamics of HL identities from a relational, spatial, and historical perspective. As the narratives unfolded, we have seen how CHL learners’ identities were developed on a historical continuum; that is, how their current positionings grew out of their past histories and led to their expectations for the future. The analysis also shows how HL identities were constructed relationally and spatially with different interlocutors across multiple sites (e.g. home, school, community, and workplace). This involved CHL learners with such complex lived experiences as meeting parental demands, achieving academically, responding to ethnic expectations/duties, and performing professional competencies — all while being Chinese and learning Chinese as an HL. Collectively, this study demonstrates three distinct trajectories of HL identity development: John’s shift from struggling to self-motivating to learn Chinese; Ryan’s from embracing the essentialist discourses to challenging them; and Lucy’s from being disempowered to empowered by being able to speak Chinese.

As pointed out by previous research, the process of identity development cannot be understood without the concept of power (Block Citation2009; Miller and Kubota Citation2013). This study has highlighted the presence of two powerful Chineseness discourses, the model minority discourse and the moral discourse on authenticity, and demonstrated how they constrained learners’ identity construction and CHL development. John and Lucy recounted how they were structured by the expectations of being a model minority. John’s life history, for example, showed his struggles to perform well academically at the expense of his HL learning at home; Lucy, on the other hand, reported how this discourse placed her in a powerless position in school, leading to her negation of being Chinese at that stage of life. As for the moral discourse on authenticity, all participants recounted a sense of embarrassment and inadequacy when being positioned deficiently due to their accented and imperfect Chinese. This sense of deficiency further structured their perceptions as CHL learners and their agency in learning and participation. Collectively, these findings highlight the fact that, while these fixed representations of Chineseness have been long regarded as positive attributes, they overlook the heterogeneity within this ethnic group and constrain the identity options available to CHL learners.

Discussion of the structural constraints provides a new perspective in understanding HL learners’ (non)participation in language learning. Unlike previous research that explained HL maintenance as either an integrative or instrumental act (e.g. Lu and Li Citation2008), this study has shown that HL learners’ language practices are structured by the power relations embedded within dominant discourses. As can be seen, all participants reported feeling ‘voiceless’ when they were positioned as deficient Chinese speakers; conversely, when they were positioned as legitimate CHL learners, they could successfully gain their ‘voice’ back and felt comfortable speaking Chinese. In a widely-cited study of five immigrant women in Canada, Norton (Citation2000) problematises the view of naturalistic settings as ideal for language learning, since immigrants do not always have the luxury to interact with native speakers and their access to English-speaking networks is socially constrained. This study extends Norton’s (Citation2000, Citation2014) findings to the context of HL learning. We show that for HL learners, even if they are surrounded by native speakers and have a natural connection to the target language, they might still avoid the opportunities to practise when the power imbalance is at work. Heller (Citation1999) points to a paradox faced by linguistic minority groups: they tend to use the same logic of monolingual/monocultural nation-state to ‘break apart the monolithic identity of the state within which they search for a legitimate place’ (p. 32). However, in order to do so, they construct a fictive unity, in our case, the essentialist Chineseness which in turn ‘produces internally structures of hegemony similar to those against which they struggle’ (Heller Citation1999, p. 32). As we have shown, these internal hegemonic discourses restrict the multiple realisations of Chineseness and have a negative impact on individuals’ participation in CHL learning and use.

Furthermore, the findings also highlight the role of human agency in the negotiation of the essentialist conception of identity and heritage. As previous studies suggest, members of a given community do not simply inherit a fixed identity, but are rather engaged in an agentive process of constructing, negotiating, and reforming (Duff Citation2013; Miller Citation2010). This agency, however, is not a priori assigned but socioculturally and historically mediated (Ahearn Citation2010). Consistent with other studies (e.g. Miller Citation2012; Ros i Solé Citation2007), this study also found that learners’ agentive capacities must be understood as emergent from their personal historicity. With respect to the participants in this study, the constraints and affordances they encountered growing up in the UK had gradually become a part of their socially formed history, which in turn, enabled them to come up with various strategies and act in new situations. These strategies, as revealed in the narratives, include reframing their thoughts to generate an inner counter-discourse, mobilising their bilingual resources to subvert power relations, and re-establishing a third space for British Chinese that enables new identity options to emerge. CHL learners’ capacity to act comes from their prior experience, but at the same time, it also maps new possibilities through its own life trajectory. It is through this process of strategic (re)positioning that our participants re-construct their identities beyond predetermined categorisations, gain more self-confidence, and continue to make progress in learning their HL.

Conclusion

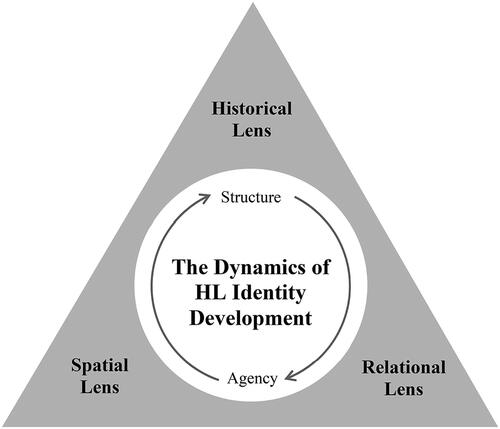

Based on a narrative inquiry of CHL learners, this study further proposes an original model to theorise the dynamics of HL identity development from a historical, relational, and spatial perspective. We argue that HL identities should be understood on a historical continuum; that is, learners’ present identities grow out of their long social histories and lead to their positionings in the future (historicity). They could also be seen as a process of interacting with different interlocutors manifested in everyday forms of power relations (relationality). Furthermore, the dynamics of HL identities are also shaped by the complex lived experience specific to a given spatial context (spatiality). Through a historical, relational, and spatial lens, we come to see the dynamic interplay of structure and agency, which leads to different trajectories of HL identity development ().

This study has important practical implications for HL education. Firstly, we argue that the responsibility for achieving success in HL maintenance should not solely rely on HL learners, as individuals’ HL learning is inevitably positioned within power relations and subject to the influences of predominant discourses. Thus, instead of blaming HL learners for not maintaining their language proficiency, we need to raise our awareness of the hegemonic pressures faced by our learners and celebrate HL learners’ heterogenous identities. Although all participants in this study gradually learned to (re)position themselves as they grew older, this may not have been possible without institutional recognition and affordances. In this regard, the study further shows the need to provide effective institutional support for the development of HL identity options. This calls for critical pedagogical approaches in HL education that create spaces for HL learners to challenge the stigmatisation, gain linguistic confidence, and (re)claim their identities as legitimate HL speakers (see also Leeman Citation2015). Secondly, contestation of the essentialist Chineseness indicates that there are multiple realisations of being CHL learners. As Blackledge et al. (Citation2008) suggest, ‘heritage’ is not a static entity, but a site of contestation and negotiation. There is no single profile of HL learners. In this sense, we argue for the need for changes in how ‘heritage’ and ‘HL learners’ are understood, so as to better reflect individual learners’ diverse linguistic backgrounds, histories, and needs. Ultimately, we hope to motivate more research to capture HL learners’ life trajectories of negotiating participation, power, and identities across multiple discursive fields. This, we further argue, could extend our understanding of how families, schools, diasporic communities, and mainstream society can make joint efforts to encourage HL learning and maintenance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abdi, K. 2011. “She Really Only Speaks English’: Positioning, Language Ideology, and Heritage Language Learners.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 67 (2): 161–190. doi:10.3138/cmlr.67.2.161.

- Ahearn, L. M. 2010. “Agency and Language.” In Society and Language Use, edited by Jaspers, J., Verschueren, J., & Östman, J. O., 31–48. 7 vols. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Archer, L., and B. Francis. 2005. “Constructions of Racism by British Chinese Pupils and Parents.” Race Ethnicity and Education 8 (4): 387–407. doi:10.1080/13613320500323971.

- Barkhuizen, G. P. Benson, and A. Chik. 2013. Narrative Inquiry in Language Teaching and Learning Research. New York: Routledge.

- Beaudrie, S., C. Ducar, and A. M. Relaño-Pastor. 2009. “Curricular Perspectives in the Heritage Language Context: Assessing Culture and Identity.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 22 (2): 157–174. doi:10.1080/07908310903067628.

- Benson, P. 2013. Second Language Identity in Narratives of Study Abroad. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Benson, P. 2014. “Narrative Inquiry in Applied Linguistics Research.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 34: 154–170. doi:10.1017/S0267190514000099.

- Bhabha, H. K. 1994. The Location of Culture. Zhou: Routledge.

- Blackledge, A., A. Creese, T. Barac, A. Bhatt, S. Hamid, L. Wei, V. Lytra, P. Martin, C.-J. Wu, and D. Yagcioglu. 2008. “Contesting ‘Language’ as ‘Heritage’: Negotiation of Identities in Late Modernity.” Applied Linguistics 29 (4): 533–554. doi:10.1093/applin/amn024.

- Block, D. 2009. Second Language Identities. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Bourdieu, P. 1991. Language and Symbolic Power. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Bucholtz, M., and K. Hall. 2004. “Language and Identity.” In A Companion to Linguistic Anthropology, edited by Duranti, A, 369–394. Williston: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bucholtz, M., and K. Hall. 2005. “Identity and Interaction: A Sociocultural Linguistic Approach.” Discourse Studies 7 (4–5): 585–614. doi:10.1177/1461445605054407.

- Cervatiuc, A. 2009. “Identity, Good Language Learning, and Adult Immigrants in Canada.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 8 (4): 254–271. doi:10.1080/15348450903130439.

- Coffey, S., and B. Street. 2008. “Narrative and Identity in the “Language Learning Project.” The Modern Language Journal 92 (3): 452–464. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00757.x.

- Clandinin, J., and M. Connelly. 2000. Narrative Inquiry: Experience and Story in Qualitative Research.1st ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.

- Craig, C. 2007. “Story Constellations: A Narrative Approach to Contextualising Teachers’ Knowledge of School Reform.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.04.014.

- Comanaru, R., and K. A. Noels. 2009. “Self-Determination, Motivation, and the Learning of Chinese as a Heritage Language.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 66 (1): 131–158. doi:10.3138/cmlr.66.1.131.

- Creese, A., A. Bhatt, N. Bhojani, and P. Martin. 2006. “Multicultural, Heritage and Learner Identities in Complementary Schools.” Language and Education 20 (1): 23–43. doi:10.1080/09500780608668708.

- Doerr, N., and K. Lee. 2013. Constructing the Heritage Language Learner: Knowledge, Power and New Subjectivities. Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Doerr, N., and K. Lee. 2009. “Contesting Heritage: Language, Legitimacy, and Schooling at a Weekend Japanese-Language School in the United States.” Language and Education 23 (5): 425–441. doi:10.1080/09500780802651706.

- Duff, P. A. 2013. “Identity, Agency, and Second Language Acquisition.” In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, edited by Gass, S. M., & Mackey, A., 428–444. London: Routledge.

- Francis, B., L. Archer, and A. Mau. 2009. “Language as Capital, or Language as Identity? Chinese Complementary School Pupils’ Perspectives on the Purposes and Benefits of Complementary Schools.” British Educational Research Journal 35 (4): 519–538. doi:10.1080/01411920802044586.

- García, O. 2009. “Livin’ and Teachin’ la Lengua Loca: Glocalizing US Spanish Ideologies and Practices.” In Language Allegiances and Bilingualism in the US, edited by Salaberry, R., 151–171. Bristol, UK; Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters.

- Gyogi, E. 2020. “Fixity and Fluidity in Two Heritage Language Learners’ Identity Narratives.” Language and Education 34 (4): 328–344. doi:10.1080/09500782.2020.1720228.

- He, A. W. 2006. “Toward an Identity Theory of the Development of Chinese as a Heritage Language.” Heritage Language Journal 4 (1): 1–28. doi:10.46538/hlj.4.1.1.

- Heller, M. 1999. Linguistic Minorities and Modernity: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography. London: Longman.

- Hirsch, E., and C. Stewart. 2005. “Introduction: Ethnographies of Historicity.” History and Anthropology 16 (3): 261–274. doi:10.1080/02757200500219289.

- Holland, D. J. W. Lachicotte, D. Skinner, and C. Cain 1998. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Hoon, C. Y. 2021. “Between Hybridity and Identity: Chineseness as a Cultural Resource in Indonesia.” In Contesting Chineseness: Ethnicity, Identity, and Nation in China and Southeast Asia, edited by Hoon, C. Y., & Chan, Y., 167–182. Singapore: Springer.

- Hornberger, N. H., and S. C. Wang. 2017. “Who Are Our Heritage Language Learners? Identity and Biliteracy in Heritage Language Education in the United States.” In Heritage Language Education: A New Field Emerging, edited by D. Brinton, O. Kagan, & S. Bauckus, 3–35. Mahwah: Routledge.

- Jing-Schmidt, Z., J.-Y. Chen, and Z. Zhang. 2016. “Identity Development in the Ancestral Homeland: A Chinese Heritage Perspective.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (4): 797–812. doi:10.1111/modl.12348.

- Kang, H. S. 2013. “Korean American College Students’ Language Practices and Identity Positioning: “Not Korean, but Not American.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 12 (4): 248–261. doi:10.1080/15348458.2013.818473.

- Kang, H. S. 2015. “Heritage Language Learning for Contesting the Model Minority Stereotype: The Case of Korean American College Students.” In Modern Societal Impacts of the Model Minority Stereotype, edited by Hartlep, N. D., 185–204. United States: IGI Global.

- Kiang, L. 2008. “Ethnic Self-Labeling in Young American Adults from Chinese Backgrounds.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 37 (1): 97–111. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9219-x.

- Kim, Y. K. 2020. “Third Space, New Ethnic Identities, and Possible Selves in the Imagined Communities: A Case of Korean Heritage Language Speakers.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education : 1–17. doi:10.1080/15348458.2020.1832493.

- Koshiba, K. 2020. “Between Inheritance and Commodity: The Discourse of Japanese Ethnolinguistic Identity among Youths in a Heritage Language Class in Australia.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education : 1–14. doi:10.1080/15348458.2020.1795861.

- Lee, J. S., and W. E. Wright. 2014. “The Rediscovery of Heritage and Community Language Education in the United States.” Review of Research in Education 38 (1): 137–165. doi:10.3102/0091732X13507546.

- Leeman, J. 2015. “Heritage Language Education and Identity in the United States.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 35: 100–119. doi:10.1017/S0267190514000245.

- Lu, X, and G. Li. 2008. “Motivation and Achievement in Chinese Language Learning: A Comparative Analysis.” In Chinese as a Heritage Language: Fostering Rooted World Citizenry, edited by He, A. W., & Xiao, Y., 89–108. Mānoa, Hawaii: Natl Foreign Lg Resource Ctr.

- Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 2014. Designing Qualitative Research. New York: SAGE Publications.

- Mau, A. 2013. “On Not Speaking ‘Much’ Chinese: Identities, Cultures and Languages of British Chinese Pupils.” Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Roehampton.

- Miller, E., and R. Kubota. 2013. “Second Language Identity Construction.” In The Cambridge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, edited by J. Herschensohn & M. Young-Scholten, 230–250. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Miller, E. 2010. “Agency in the Making: Adult Immigrants’ Accounts of Language Learning and Work.” TESOL Quarterly 44 (3): 465–487. doi:10.5054/tq.2010.226854.

- Miller, E. 2012. “Agency, Language Learning, and Multilingual Spaces.” Multilingua 31 (4): 441–468. doi:10.1515/multi-2012-0020.

- Mu, G. M. 2014. “Heritage Language Learning for Chinese Australians: The Role of Habitus.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35 (5): 497–510. doi:10.1080/01434632.2014.882340.

- Ng, J. C., S. S. Lee, and Y. K. Pak. 2007. “Contesting the Model Minority and Perpetual Foreigner Stereotypes: A Critical Review of Literature on Asian Americans in Education.” Review of Research in Education 31 (1): 95–130. doi:10.3102/0091732X07300046095.

- Norton, B. 2000. Identity and Language Learning: Gender, Ethnicity and Educational Change. Harlow: Longman.

- Norton, B. 2014. “Identity and Poststructuralist Theory in SLA.” In Multiple Perspectives on the Self in SLA, edited by S. Mercer & M. Williams, 59–74. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Norton, B., and K. Toohey. 2011. “Identity, Language Learning, and Social Change.” Language Teaching 44 (4): 412–446. doi:10.1017/S0261444811000309.

- Park, M. Y. 2021. “Language Ideologies, Heritage Language Use, and Identity Construction among 1.5-Generation Korean Immigrants in New Zealand.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism : 1–13. doi:10.1080/13670050.2021.1913988.

- Pavlenko, A. 2007. “Autobiographic Narratives as Data in Applied Linguistics.” Applied Linguistics 28 (2): 163–188. doi:10.1093/applin/amm008.

- Pavlenko, A., & Blackledge, A., eds. 2004. Negotiation of Identities in Multilingual Contexts. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. 1988. Narrative Knowing and the Human Sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Ros i Solé, C. 2007. “Language Learners’ Sociocultural Positions in the L2: A Narrative Approach.” Language and Intercultural Communication 7 (3): 203–216. doi:10.2167/laic203.0.

- Rothman, J., and D. P. Y. Cabo. 2012. “The (Il)Logical Problem of Heritage Speaker Bilingualism and Incomplete Acquisition.” Applied Linguistics 33: 450–455.

- Seidman, I. 2006. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. 3rd ed. New York; London: Teachers College Press.

- Showstack, R. E. 2012. “Symbolic Power in the Heritage Language Classroom: How Spanish Heritage Speakers Sustain and Resist Hegemonic Discourses on Language and Cultural Diversity.” Spanish in Context 9 (1): 1–26. doi:10.1075/sic.9.1.01sho.

- Showstack, R. E. 2017. “Stancetaking and Language Ideologies in Heritage Language Learner Classroom Discourse.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 16 (5): 271–284. doi:10.1080/15348458.2016.1248558.

- Taylor, F. 2014. “Relational Views of the Self in SLA.” In Multiple Perspectives on the Self in SLA, edited by S. Mercer & M. Williams, 92–108. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Train, R. 2007. “Real Spanish’: Historical Perspectives on the Ideological Construction of a (Foreign) Language.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies 4 (2–3): 207–235. doi:10.1080/15427580701389672.

- Tseng, A. 2020. “Identity in Home-Language Maintenance.” In Handbook of Home Language Maintenance and Development, edited by A. C. Schalley & S. A. Eisenchlas, 109–129. Berlin; Boston: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Tseng, A. 2021. “Qué Barbaridad, Son Latinos y Deberían Saber Español Primero’: Language Ideology, Agency, and Heritage Language Insecurity across Immigrant Generations.” Applied Linguistics 42 (1): 113–135. doi:10.1093/applin/amaa004.

- Wong, K. F., and Y. Xiao. 2010. “Diversity and Difference: Identity Issues of Chinese Heritage Language Learners from Dialect Backgrounds.” Heritage Language Journal 7 (2): 314–187. doi:10.46538/hlj.7.2.8.

- Woolard, K. 1998. “Introduction: Language Ideology as a Field of Inquiry.” In Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory, edited by B. Schieffelin, K. Woolard and P. Kroskrity. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wortham, S. 2001. Narratives in Action: A Strategy for Research and Analysis. New York; London: Teachers College Press.