Abstract

Thinking together in primary classrooms has received much scholarly attention in recent years, with a focus on educational dialogue at the forefront of studies concerned with identifying what constitutes effective language for learning. Whilst the expression of explicit reasoning is often discussed, less attention has been given to the role that provisionality or vague language plays in supporting the articulation of ‘thinking aloud in action’. In this study, we draw on data which comprised recorded lessons of primary-aged children (8–10 years old) in whole class and small peer-group learning contexts. Using linguistic ethnography we examine the data for patterns of specific vocabulary associated with reasoning and provisional or vague language. We then identify episodes in the transcripts where the language co-occurs. Tracking two children’s contributions, we are able to note the differences in their articulation of ideas in the different learning contexts of whole class and small group. We conclude that not only is thinking aloud complex, fluid and provisional, but that ‘epistemic modality’ supports reasoning by allowing a tempering of proposed ideas and by appealing to listeners by referencing shared experiences. The small group or larger whole class contexts change this relationship, though not necessarily as expected.

Introduction

The role of language and dialogue in learning has received significant attention in recent years, with dialogic pedagogy espoused as educationally valuable and productive (Alexander Citation2020; Hardman Citation2019; Howe et al. Citation2019). Specifically, the discourse features used in classroom dialogue that indicate higher order thinking and explicit reasoning have been a focus of many studies (for example, Howe et al. Citation2019; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Soter et al. Citation2008).

A smaller number of studies have looked at the role of provisionality in the articulation of reasoning, considering the language of possibility in supporting the development of collaborative meaning-making between students. Boyd, Chiu, and Kong (Citation2019) have explored possibility as part of reasoning, and Maine (Citation2015) has previously argued that possibility thinking (Craft Citation2000) expressed through modal vocabulary such as maybe, perhaps, and might enables negotiation and intersubjectivity between speakers, playing a central part in the joint construction of meaning.

Even less attention has been given to the role of ‘linguistic vagueness’ and how speakers might use this as a tool as they formulate and propose ideas. Despite the lack of its clear delimitation, linguists agree that vagueness is a pervasive linguistic feature in spoken language with a socially cohesive function (Channell Citation1994; Carter and McCarthy Citation1997, Citation2006; Fairclough Citation2003; O’Keeffe, McCarthy, and Carter Citation2007, Martínez Citation2011). Whilst the meanings of vague expressions are ‘inherently and intentionally imprecise’ (Cutting Citation2007, 4), vague language has important pragmatic discourse functions, such as enabling speakers to gain the floor, acting as place holder while ideas are being formulated, or allowing speakers to propose ideas tentatively (Rowland Citation2007).

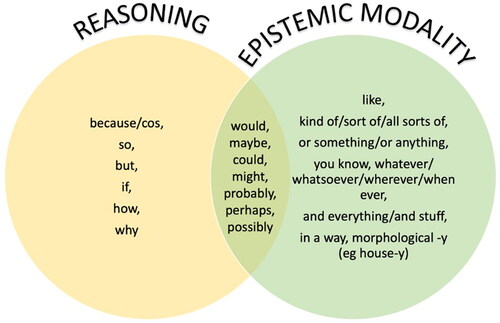

Coates (Citation1987) includes vague terms such as kind of and sort of alongside modal verbs and adverbs such as might, maybe and possibly within her definition of ‘epistemic modality’ and argues that one function of this is to ‘reduce the force’ (p. 127) of an utterance, particularly where the topic is sensitive, and enables the maintenance of social harmony, also argued by Maine (Citation2015).

In our data drawn from classroom observations and recordings as part of a large European project aiming to support children’s development of dialogue as a social practice (DIALLS Citation2021a), we noticed that the language of reasoning, possibility and vagueness occurred regularly in dialogic classroom discussions, but seemed different in whole class (WC) and small group (SM) learning contexts. We hypothesised that because WC discussions are more structured, they included the presentation of more clearly articulated thinking from students, whereas SM peer discussions might be less coherent and more provisional as children tried out their ideas together and negotiated joint meanings. We found that little has been written on how epistemic modality is manifested in these different learning and social contexts, or about how it might enable students to ‘think aloud’ and present their ideas to their peer audiences. Thus, in this paper, we investigate patterns in the use of provisional language and linguistic vagueness, as students manage the social context of their discussions whilst formulating ideas together in WC and SM. Building on previous work where we adopted linguistic ethnography to enable a macro and micro level analysis of dialogic classrooms (Maine and Čermáková Citation2021), we again make use of this approach, using the two perspectives iteratively to identify linguistic patterns that we then look at more qualitatively. We particularly examine discourse features frequently identified as being indicative of reasoning and possibility, extending this to also incorporate vague terms that can be considered indicative of epistemic modality. We then use a macro level, corpus linguistic approach to identify spells of dialogue where they work together, noticing the learning contexts in which they are used as tools for thinking aloud. Microethnographic analysis (Bloome et al. Citation2005) enables us to see these bounded literacy events as diverse social learning contexts, and to explore how language is used in them as a tool for thinking aloud.

We hypothesise that provisional language and linguistic vagueness play an important but overlooked role in classroom talk, both socially and cognitively, and specifically ask: How does epistemic modality support reasoning as primary children think aloud in whole class and group discussions within dialogic classrooms?

Theoretical foundations

Our research is framed by sociocultural theory placing Vygotskian notions of thought and language as central to learning (Citation1962, Citation1978). Wertsch (Citation1991) suggested that, ‘We need to develop the type of theoretical frameworks that can be understood and extended by researchers from a range of what now exist as separate disciplinary perspectives’ (p. 4), and whilst not all research examining classroom talk comes from a sociocultural starting point, many authors using this framework (see for example work by Mercer, Rojas-Drummond or Hennessy) have found it a useful basis on which to conduct empirical research. Crucially, a sociocultural perspective centralises the importance of talk for learning within its social context, considering how ideas are constructed as children think together.

Research conducted over several decades has shown that how children talk and are talked to in the classroom influences their learning outcomes (see, for example, Alexander Citation2018, Citation2020; Hardman Citation2019; Howe et al. Citation2019; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Nystrand et al. Citation1997; Sinclair and Coulthard Citation1975; Soter et al. Citation2008; Wilkinson et al. Citation2017). Investigating the productivity of classroom dialogue in English primary classrooms, Howe et al. (Citation2019) summarised the research identifying features of dialogic classrooms as including five recurring themes. These include: open questions rather than closed ones; extended contributions and elaboration; differences of opinions that are explored, acknowledged and reasoned; integrated lines of enquiry that are linked and coordinated; and the students’ metacognitive awareness of their reasoning and talk. A simultaneous study (Hardman Citation2019), also looking at classroom talk, noted the impact of professional development on leading teachers to adopt more dialogic pedagogies on learning outcomes for ten-year-old children, finding a two-month learning gain in core curriculum subjects.

Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes (Citation1999) investigated peer group interactions and identified ‘Exploratory Talk’ which included explicit reasoning as educationally valuable. Rojas- Drummond and colleagues developed this further with the idea of co-constructive talk as, ‘taking turns, asking for and providing opinions, generating alternatives, reformulating and elaborating on the information being considered, coordinating and negotiating perspectives and seeking agreements’ (Rojas-Drummond et al. Citation2006, 92). In the US, the ‘Quality Talk’ study generated important findings regarding the efficacy of different small group reading contexts (Murphy et al. Citation2009; Soter et al. Citation2008), with specific discourse features used as ‘proximal indicators’ of high level comprehension (Soter et al. Citation2008, 377).

Within the dialogic contexts for learning of peer groupwork, the language of reasoning has been studied extensively. Mercer and colleagues’ seminal work (1999) and their ‘Thinking Together’ project centralised key linguistic markers of reasoning (I think, because, agree) with further studies examining the discourse features of reasoning building on these (for example, Soter et al. Citation2008). Both studies also included modal and questioning vocabulary (could, would, maybe, how, why) and noted that they often signalled the start of reasoning. Boyd and colleagues (Boyd and Kong Citation2017; Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019) developed this by grouping reasoning into three categories: the language of possibility (e.g. maybe), reasoning links (so, if, because) and ‘pressed for’ reasoning (how, why) (Boyd and Kong Citation2017). They argued that possibility (termed ‘speculation’ by Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019) and reasoning words serve as a ‘proxy of local discourse conditions cultivating dialogic talk’ (Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019, 25).

Maine also explored the role of the ‘language of possibility’ in opening up dialogic spaces that are fluid, provisional and centred on what might, or could, be (Citation2015, 64). This concept builds on the work of Craft (Citation2000) who placed questioning and imagining at the centre of possibility thinking. In Hardman’s (Citation2019) study, extended student contributions including speculation and imagination were also analysed as part of the dialogic discourse reflecting Alexander’s (Citation2018) repertoire of learning talk.

Epistemic modality

A dialogic classroom is an inclusive environment where all discourse participants are given a chance to contribute and all ideas are valued. Participants should feel encouraged to share their reasoning together, without feeling their ideas will be dismissed or ridiculed. In such an environment, ideas are suggested or proposed rather than stated as fact. Linguistically, this is frequently enabled by ‘epistemic modality’, which is ‘concerned with the speaker’s assumptions, or assessment of possibilities, and, in most cases, it indicates the speaker’s confidence or lack of confidence in the truth of the proposition expressed’ (Coates Citation1987, 112). While traditional accounts of epistemic modality link it to the conveyance of ‘possibility’ (as opposed to ‘necessity’ in deontic modality), Lyons (Citation1977) also introduced the element of subjectivity – ‘the speaker explicitly qualifies his commitment to the truth of the proposition’ (p. 797) in addition to the more objective evaluation of the probability of the truthfulness of the statement.

Epistemic modality traditionally involves auxiliary modals such as might and may and certain adverbs and adjectives like maybe and possible (Portner Citation2009, 2). However, as Coates (Citation1987, 111) notes, auxiliaries and prototypically modal adverbs and adjectives are part of ‘a much wider system’ of modality; and in examples, she discusses vague qualifiers kind of/sort of in spoken discourse. In his work on classroom discourse in mathematics lessons, Rowland (Citation2007) found that less precise vague language and hedging was used by students when they were not completely committed to the idea they were proposing. Words such as sort of and about were used to ‘blur’ precise measures (p. 82). Carter and McCarthy (Citation2006, 921) describe vague language as words or phrases ‘which deliberately refer to people and things in a non-specific, imprecise way’. In her seminal book, Vague language (1994), Chanell discusses, for example, vague category identifiers (or something, and whatnot, kind of), or placeholder words such as thingy. Linguistic vagueness is multifunctional; it may be strategic and intended but it may be also unintentional as the conversation subject may not require precision, such as in the social contexts of Maybin’s research in schools (Citation2009). Vague language may be used for strategic imprecision where the speaker deliberately withholds information for reasons of politeness, self-protection or humorous effect, or the speaker may lack precise information or knowledge of specific vocabulary (Channell Citation1983, Citation1994). It may also function as a ‘performance filler’ (Channell Citation1983, 104). Vague language is crucial for ‘interpersonal meaning’ that is built on shared knowledge and it can mark ‘in-group membership’ (Carter and McCarthy Citation2006, 202) and hence also has an important pragmatic function.

Taking this previous research together, in our paper we hypothesise that some of the functions of vague and possibility language are similar as they both achieve epistemic modality, and so rather than grouping the language of possibility as part of reasoning (following Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Soter et al. Citation2008), we examine possibility as a separate, supporting phenomenon propelled by modal words such as might, maybe and could. We then also examine a group of vague words such as adaptors (e.g. sort of/kind of) and extenders (e.g. or something). Together, these two groups of words are considered as markers of epistemic modality.

Process or product

We have chosen primary classrooms (specifically 8–10 year olds) for our analysis, as situational contexts where children regularly move in and out of WC discussions, which may be related to ‘reporting’ ideas, or collaboratively co-constructing them, and SM discussions, which are symmetrically structured to generate collaborative thinking. Linell, Gustavsson, and Juvonen (Citation1988) note that the peer group offers the most symmetrical potential for discussion; as in theory, participation is equally positioned in terms of power and responsibility. Whilst in practice this might not be so apparent (see, for example, Maine et al. Citation2020), the social context of having a smaller audience on which to test ideas is clearly more conducive to engagement than a wider whole class.

Mercer and colleagues noted that in groupwork much of the talk could be defined as either disputational or cumulative (Citation1999) and not the highly desirable ‘Exploratory Talk’ that would reflect reasoning. Similarly, Howe et al. (Citation2019) have focused on the idea of ‘productive’ talk having explicit reasoning and positioning. Indeed, clarity and precision are at the heart of the English National Curriculum which states that ‘Pupils should be taught to speak clearly and convey ideas confidently using Standard English’ (DfE Citation2013). However, if SM talk is considered part of the process of thinking aloud, forming, reforming, restating and repeating ideas could be argued to be part of collaborative meaning-making, presenting a tension with what is assumed to be appropriate language in the classroom (Cushing Citation2021; Snell and Cushing Citation2022).

In his study of classroom discourse during mathematics lessons, Rowland (Citation2007) makes an important distinction between the ‘product’ as an unambiguous, precisely worded mathematical formulation and the ‘process’ of mathematics production, the verbalised thinking process which is ‘characterized by a number of forms of vagueness’ (p. 80). Here, possibility and vagueness allow for ideas to be held, shaped and negotiated.

The focus on the ‘product’ of idea presentation as a standard form (Alexander Citation2020; Cushing Citation2021) suggests that the only language valued in classrooms should present thinking as a neat and complete, overlooking the messy processes by which it might be attained. Reflecting on his seminal work investigating classroom talk, Barnes (Citation2008) highlighted the value of exploratory talk as the trying out of ideas in contrast with ‘presentational talk’ (p. 5) where ideas were reported, and thus necessarily more structured.

Methodology

Linguistic ethnography (LE) offers the benefits of combining quantitative, data-driven approaches with qualitative analysis focusing on bounded communicative events (Bloome et al. Citation2005) and so is an appropriate methodological approach for a socioculturally positioned study. Proponents of the LE approach highlight the importance of looking at language in context, moving beyond theorised ideals of language modes, into the reality of discourse in action. This is significant in classrooms where social norms, power structures and pedagogy impact on the mode of talk that is encouraged, included and celebrated (Maybin Citation2009). An LE perspective recognises that there is a significant difference for children testing out ideas in the SM peer context, and testing ideas in the larger WC environment. The ethos of a dialogic classroom (Alexander Citation2020; Aukerman and Boyd Citation2020) aspires to embrace inclusive, tolerant and empathetic dispositions from its participants, yet it would be naïve to assume that there are no contextual factors favouring some voices over others. Adopting LE means that the patterns of discourse that are illuminated by a linguistic analysis can direct attention to insightful episodes of talk that might demonstrate differences in how language is used as both a learning and social tool (Copland and Creese Citation2015; Maine and Čermáková Citation2021). That said, the goals of LE to simultaneously engage the ‘holistic nature of ethnography with the systematic rigour of linguistics’ (Rampton Citation2007) have been criticised as over-ambitious by some authors (see, for example, Hammersley Citation2007) who warn of the dangers of achieving neither goal satisfactorily. We mitigate this criticism by moving iteratively between the two stances, checking we are analysing the larger sets of data with the integrity of Corpus Linguistics, but always considering the nuance of how the language fits within its bounded event (Bloome et al. Citation2005) and how this potentially impacts on how it is used to express, create or co-construct ideas. Thus, rather than falling between two positions, we move between them, an approach made possible by the academic expertise of the authors, one a corpus linguist, and the other an educational researcher who uses sociocultural perspectives in her theoretical and empirical work. This collaboration allowed us to challenge each other from our own theoretical and methodological positions, to satisfy the rigour and nuance of both approaches.

In this paper, we look for patterns in language use within the contexts of WC and SM discussions, using a data-driven, quantitative analysis to unpack the linguistic strategies apparent in the children’s talk. Noticing more than simply the ‘high value’ language of explicit reasoning, we are thus able to consider how ideas are proposed, shared and negotiated within these spaces, acknowledging the importance of creating genuine space for collaborative knowledge creation.

Research context

We use a subcorpus of transcribed classroom discussions created as part of the DIALLS project (DIALLS Citation2021b), focusing particularly on ten lessons involving primary-aged children aged (8–10 years old). The project was focused on the development of children’s cultural literacy through the enhancement of their dialogue skills, with a focus on classroom discussion and the exploration of cultural ideas and values. The recorded lessons were part of a programme in which wordless films were used as stimuli for discussions around cultural values. The lessons involved the children watching a short film and then discussing key themes that were specified in a lesson plan. The structure of each lesson meant that the children talked first about the theme (for example ‘home and belonging’) in the context of the film, then moved into a more philosophical or abstract discussion of the themes. Each lesson included roughly 45 minutes of recording capturing WC and SM discussions. The SM groups (each comprising four children) were selected by the teachers of classes, as typically children who they felt would work well together and not be daunted by being recorded. They were not formally assessed for language competence. The classes analysed here represented classes typical of their rural and semi-rural/small town contexts. Classes were average-sized for English primary schools (24–30 pupils). There were small numbers of children with English as an Additional Language (between 8% and 20%) in the classes (none of the children in the SM groups). Publicly available socioeconomic data suggested that the schools had fewer disadvantaged children than the national average of 19.7% (the schools had between 3.6% and 7.2% of children receiving Free School Meals, the indicator of economic disadvantage in English schools). Whilst the larger dataset includes transcribed lessons from three age groups (5–6, 8–10 and 14–15 year olds), the 8–10 year old age group was chosen for focus as all lessons in the dataset included both WC teacher led discussions and SM peer discussions (without a teacher present). Additionally, an initial quantitative analysis as part of the wider DIALLS dataset had revealed a significant frequency of the language of reasoning and possibility in these lessons, in addition to more clearly evident dialogic practices (Maine and Čermáková Citation2021). In the classes analysed, teachers moved fluidly between WC and SM, either inviting the children to discuss their ideas about the topic first before feeding back to the whole class, or by starting with a WC discussion and asking children to continue the discussion in their own groups.

We further divided the dataset to isolate teacher and student talk and WC and SM discussions. As we were specifically interested in how epistemic modality was reflected in student talk, the teacher talk was excluded from the quantitative analysis. However, we necessarily included the teacher’s talk in the qualitative analysis as it gave an important context for how children were invited to develop or present their thinking, and how teachers modelled their own thinking processes. There was a third context in some classes, that of the teacher guided small group (TG) discussions and we noted that this learning context was of potential interest, not least because the TG has previously been highlighted as a particularly effective learning context for reading instruction (Murphy et al. Citation2009; Soter et al. Citation2008). However, a close analysis of the TG data revealed inconsistencies in how the teachers had used this mode of teaching (for example, dropping in quickly to add a point or hear a summary, or more specifically taking a role as a participant in the group), and as these occurrences were scarce in the data, we did not find them to be reliably comparable. Hence our final dataset includes only SM and WC discussions.

The lessons were transcribed using a simplified Jeffersonian transcription system. The transcription does not include prosodic features or the length of the pauses, notates emphasised words by capitalisation and shows overlapping speech with squared brackets. The transcription avoids any language standardisation features – all repetitions, non-standard forms and hesitation sounds (uhm) are included. All participants have been fully anonymised and all gave consent for their discussion to be recorded, analysed and presented. Ethics were approved through Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge procedures and as part of EC Horizon2020 grant 770045.

The linear representation of turns in the transcription is the most common format to represent spoken language in writing (Adolphs and Knight Citation2010) and we used the ‘turn’, a speech stretch by one speaker (which may include overlapping speech), as our basic unit of analysis in the quantitative overview. Drawing on previous research (Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019; Maine Citation2015; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Soter et al. Citation2008), we compiled a list of ‘reasoning’ and ‘possibility’ words as proxies for a possible occurrence of this type of language. Using a Python script, we extracted from our subcorpus all turns.

Table 1. List of Reasoning, Possibility and Vague (RPV) words and phrases (ordered according to their frequency of occurrence).

Capturing linguistic vagueness is necessarily more complex and less established and thus is an inherent part of our analytical procedure. Based on previous research (Channell Citation1994; Coates Citation1987; Rowland Citation2007), we identified vague words and phrases in the data manually, specifically focussing on words that repeatedly occur in functions that support the thinking verbalisation process; in our data, these were, for example, words and phrases such as like, sort of/kind of, or something, and stuff. The final list of words that were used as proxies for Reasoning and for Possibility and Vagueness as signals of Epistemic Modality, are presented in : ‘reasoning’ and ‘possibility’ words being collated from previous research and vague words and phrases have been identified in a data driven way. Many of these words are multifunctional, for example, because can function as a logical operator but also as a discourse marker. The item that is perhaps the most multifunctional is like, see below for further discussion. All these words are mere proxies for our macro-level overview, we examine them further in their context in our qualitative part of the analysis.

The episodes we used for our qualitative analysis are drawn from a lesson where children engaged in WC and SM discussions about the meaning of ‘home’ after watching a short film about a baboon living on the moon (Duriez Citation2002). This lesson was chosen as it offered multiple opportunities for children to engage in discussions, both to make sense of the ambiguous short film, and also to have a discussion that transcended the text into more personal or philosophical territory. The episodes were identified as a result of our quantitative analysis – they contain RPV language and feature speakers that contributed both in WC and SM discussions.

Quantitative analysis

Once the dataset had been managed to enable the isolation of SM and WC contexts, and to delineate teacher and student talk in WC, we were able to quantify the RPV language across these contexts. There were 4229 student turns in total (1308 in WC and 2921 in SM). Within these, we found the RPV language present in 573 WC turns (44%) and 922 SM turns (32%). We then analysed the co-occurrence of the RPV language in these turns (see ).

Table 2. Occurrence of proxy words for Reasoning, Possibility and Vagueness (RPV) in WC and SM.

The quantitative overview confirmed that indeed, reasoning and epistemic modality occurred together, though not always, and less than we expected, particularly in the SM. When considering RPV turns that included Reasoning together with Possibility and/or Vague language, they represented 46% (WC) and 27% (SM) of RPV turns. Interestingly, in RPV turns in SM, 45% of turns displayed reasoning proxies only and did not include any of our markers of epistemic modality (compared to 34% in WC), suggesting children were able to express their arguments explicitly to their SM peers without the need to build in an element of possibility or subjectivity. This also potentially signalled less collaboration and negotiation of ideas as the children each stated their opinion rather than proposed it.

The use of Possibility vocabulary was interesting, as the context of WC or SM did not seem to impact its occurrence with either Reasoning or Vagueness in terms of frequency. However, the proportion of Reasoning turns that included Vagueness or Vagueness together with Possibility proxies were much greater in WC (23% in WC as opposed to 13% in SM and 14% in WC and 5% is SM respectively); suggesting that the changed context of presenting ideas to a wider WC audience potentially meant less eloquence in thinking aloud. Teachers used these WC contexts in different ways, sometimes to initialise discussions (process) before moving the children into SM and other times as ‘reporting back’ (product) style plenaries. Remembering that vague vocabulary is multifunctional, the presence of it here might also be related to the social context of speaking in front of many peers serving the function of ‘performance filler’ rather than supporting the provisionality of thinking aloud in action; the following qualitative analysis allows us to examine this carefully.

Qualitative analysis of findings

The frequent occurrence of vague words such as like and kind of in WC led us to examine closely what was happening as children moved between SM and WC – either to report back their thinking, try their own ideas on a wider group, or give initial responses to the whole class before exploring them more in detail in groups. The LE approach meant that we were aware of the boundaries of these different communicative events (Hymes Citation1972) and we were able to examine the potential social impact of thinking aloud in the two different contexts. It also enabled us to see the differences between the teacher introducing an idea to the WC that was then discussed in more detail in SM, or where teachers asked an initial question, gave the children a chance to discuss it and rehearse their ideas in the SM context, then used the WC as a plenary discussion. This was particularly useful where we were able to notice the contributions of children who participated in WC discussions and were also part of the SM that we were recording. Hence, we filtered our transcripts to find corresponding WC and SM discussions where this happened and where the three types of proxy indicators (RPV) occurred together.

We next present a linguistic analysis of the contributions of two children, Alice and Lucy, who both participated in the WC discussion before working together in the SM. Looking at the linguistic patterns of their main contribution point in each context allows us to unpack the interplay of reasoning and epistemic modality in the two different contexts. Considering these contributions in the wider discussions that they were part of highlights how the social context might have affected them.

The whole class (WC) discussion

In our examples, the teacher has just introduced the idea that ‘home’ might mean something different to each of us, and that this might be further complicated if people relocate, move house or leave home as they grow up. The transcript shows the line number from the original corpus, the RPV vocabulary is emboldened.

Example 1.

Alice and Lucy in the whole class (WC)

Alice’s WC main contribution

Alice is the first speaker to follow the teacher’s idea. It is interesting to note that the teacher does not ask for a response – she simply expresses her view, waits, and the children respond (see Maine and Čermáková (Citation2021) for an exploration of the nuance of dialogic teaching styles). In her contribution (line 382), Alice builds a hypothetical scenario with an if-clause and builds provisionality into her the statement with the use of kind of and like. She uses the pronouns you and your to appeal to her WC audience and relate to their lives. At the end of this, she invites Lucy to speak, acknowledging perhaps that they had overlapped in trying to gain the floor.

Lucy’s WC main contribution

Lucy’s turn (line 383) starts as an overlapping speech as she cuts into the end of Alice’s turn. She uses actually in the turn as hedging, which in her speech signals disagreement with what was previously said (I think actually…), and this gains her the floor to speak though this now puts her under pressure to present an idea; so turning her thoughts into a neatly worded idea appears initially a struggle and vague language is prominent. She repeats actually, but no longer in adversity, and this is followed by a chain of causal cos/because. After a less coherent start, the logical construction using but, like, and if helps her to streamline her thought presentation. While in the first part of her turn she describes moving as general (everyone) and also draws on her own experience (I moved), after but, like and if she switches to the second person pronoun, you, referencing shared experience and knowledge, drawing the class audience into her perspective. She opens up a dialogic space of possibility (Maine Citation2015) by the use of modals would, could and maybe, couching her idea in provisionality and acknowledging the possibility of alternatives.

Lucy’s turn is 81 words and she uses like nine times. The first five likes appear to be performance-related, though her idea is being helped formulated by this linguistic vagueness. The sixth, eighth and nineth like (underlined in turn 383) also have a powerful comparative function. Note, for example, the sixth occurrence of like – though Lucy speaks about my new house, the fact that she says like my new house, makes her house an example of an experience that others can possibly relate to, she thus draws again on the shared knowledge and similarity of experience with her audience.

The continuation of the WC discussion

Lucy continues to be the main contributor in the discussion after her initial input. The teacher very much takes a back step, mostly acknowledging and affirming Lucy’s contribution – which emboldens her to continue. On line 384, the teacher directs her back to the main focus of the discussion, though mostly Lucy continues her own line of thinking (387). She then continues to develop this idea across several turns while the teacher backchannels with yeah. Lucy explains her reasons (line 389) using because linked to the modal might. She again uses actually to emphasise that the hypothetical scenario she is suggesting needs to be considered seriously. The teacher follows up with a question to elicit further thinking (392). This seems to break the flow of Lucy’s thinking (393, 395) signalled by uhm, increased use of vague expressions (like, sort of – though not all instances of like are vague); repetition (he); and possibility (might and maybe). The chaining of these devices shows how she makes an effort to articulate the hypothetical scenario in her head. She is, however, uncertain and leaves the possibilities open, finishing off with the general vague extender (or something) which serves to temper her point.

The small group (SM) discussion

Lines 398–408 of the transcript (not included here) involve the teacher setting up the SM discussion, asking the children to focus on what is special about home and to explore their differing perspectives. Our second example picks up at the point where the children have now moved into the SM discussion.

Example 2.

Alice and Lucy in the small group (SM)

Alice starts the discussion (409) by setting a cooperative tone (same as everyone) but at the same time, she tries to steer the discussion, she uses the modal should and then shares her view based on her personal experience. She finishes her turn with the modal would to suggest that under certain conditions this could be so. She then uses an if-clause which specifies why this is only provisionally so. In her second significant turn (415), she follows a similar pattern – making her suggestion (this time to counter Lucy) – but tempering it at the end by adding kind of (it still does kind of link).

In the SM, Lucy now appears able to formulate her thinking by including far less epistemic modality. She again asserts herself as a speaker, she confidently voices her disagreement I disagree… because … (line 412) and she directly builds on her own contribution from the WC, where she had the opportunity to formulate her idea in her interaction with the teacher. Her speech is fairly fluent with less frequent linguistic vagueness. She does not use possibility words and even though the end of the turn is vague, it does not leave an invitation for others to add their views (It’s just ‘cos uhm).

Discussion and conclusions

Isolating the language of possibility from the language of reasoning and reconsidering it as indicative of a wider category of epistemic modality, enabled a close-up analysis of how children think aloud in action in different learning contexts. It also highlighted how vague language which could easily be dismissed in its lack of structure and explicitness supports the reasoning process in a social context (see ).

The classrooms that we analysed all had the features of dialogic pedagogy; that is, talk for learning in WC and SM contexts was the norm, with elaborated responses common (see earlier section). The teachers used WC and SM interchangeably and flexibly and the children were used to sharing their ideas. Of course, this can also be seen as a limitation of the study as it can be argued that already these classes presented an educationally productive ethos (Alexander Citation2020; Howe et al. Citation2019; Wilkinson et al. Citation2017). However, concentrating on these classrooms enables a fine-grained analysis of exactly how they enable students to engage more deeply in such contexts, showing the value of a dialogic pedagogy.

The data showed that the occurrence of the language of reasoning and epistemic modality was more evident in WC than in SM learning contexts. We had hypothesised that the presence of epistemic modality in the WC would be more related to performance in front of a peer group, with the SM being the space for fluid and provisional idea generation. Whilst this may be true in some classrooms, qualitative analysis of our data showed that in some classrooms, children (in our example, Lucy) appeared just as able to engage in ‘thinking aloud in action’ in WC discussions; that is, regardless of the changed social dimension of audience size and a/symmetrical structures. Extending our analysis to consider what the teacher was doing in this exchange, it became clear that she was able to encourage an extended response by using small but significant acknowledgements. Subsequently, Lucy was then able to think on the spot with less a presentation of explicit reasoning, and more spontaneous thinking. The supportive dialogic environment that Alexander (Citation2020) describes was evidenced here, illuminated by the qualitative analysis of LE. Without the LE perspective, the assumption that vagueness in WC contexts is just related to performance would stand, as opposed to the recognition that in fact in a highly dialogic classroom, the WC context might afford similar opportunities to SM for thinking aloud in action.

In our data, both modal verbs/adverbs (i.e. the language of possibility) and vagueness both appear to frequently convey epistemic modality. However, where modal vocabulary appears similarly in both WC and SM contexts, the frequency of vague language was significantly greater in the WC. Investigating this vague language further, it became clear that it also allowed some tempering of idea proposal, particularly when used as the final part of a turn to offer the point as negotiable (evident in Alice’s turns) and therefore appealing and inviting to others.

Our investigations highlight that there is an inter-relationship between reasoning and epistemic modality but it is not straight-forward. Where previous authors have acknowledged the role of modal language in opening up a space for speculation (Boyd, Chiu, and Kong Citation2019; Mercer, Wegerif, and Dawes Citation1999; Soter et al. Citation2008), by also including vague language as part of a broader category of epistemic modality, we find that it does more than simply signal speculation. Our analysis illustrates how not only does epistemic modality show the process of thinking aloud in action, which is not a fully formed and explicitly articulated presentation, but it also enables an appeal to the audience by generalising and using, for example, second person pronouns to refer to possible shared experiences that are not defined, just suggested.

The implication for this in teaching is significant. Thinking aloud is complex and messy, and also involves the social considerations of not only making a point accountable to one’s peers (Wolf, Crosson, and Resnick Citation2006), but appealing to them too. We find, then, in our data, evidence of other factors that have roles in the proposition of ideas, such as repetition of words such as actually, and the use of general extenders and category identifiers (e.g. or something) to invite listeners to fill the gaps with their own ideas, to collude with the point being made. However, as Snell and Cushing point out in their paper (Snell and Cushing Citation2022), whilst Speaking and Listening have a place in the English primary curriculum, the emphasis on Standard English or the rehearsal of ideas before committing them to writing means that thinking aloud in action is not valued, particularly in whole class contexts where children are expected to express their ideas clearly and articulately. Our data show how constructing ideas in front of one’s peers with the teacher in the WC can model accountable thinking and talk (Wolf, Crosson, and ResnickCitation2006) and model the process of engaging in high level thinking. Worryingly, Snell and Cushing (Citation2022) demonstrate that an increasing focus on the correct grammatical forms in talk inhibit high levels of thinking and they cite cases where words such as like are simply banned in the classroom thus undermining the use of language as tool to support thinking. Analysing classroom language using a sociocultural framework, and specifically linguistic ethnography as a tool to unpack language as it happens in WC and SM contexts allows us to examine the value of allowing children to experiment with ideas and build their confidence in speaking in the whole class.

This then leads to a reflection of dialogic classrooms and how thinking aloud might be realised within them. Following the ideas of Alexander’s (Citation2020) dialogic ethos and Aukerman and Boyd’s (Citation2020) dialogic value orientations, such a space should naturally include the proposition of half-formed ideas to the wider group, in addition to explicit reasoning or clear articulation of ideas promoted as typical of productive classroom dialogue. The ‘process’ of thinking in action must be valued in addition to the ‘product’ of clearly articulated, explicit reasoning, to support children to deeper dialogical thinking, which might include changes of direction or contradictions. Epistemic modality is evidence of the use of language as a tool for thinking, not just a tool for presentation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the teachers and children who participated in the study

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adolphs, S., and D. Knight. 2010. “Building a Spoken Corpus.” In The Routledge Handbook of Corpus Linguistics, edited by A. O’Keeffe and M. McCarthy, 38–52. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Alexander, R. 2018. “Developing Dialogic Teaching: Genesis, Process, Trial.” Research Papers in Education 33 (5): 561–598. doi:10.1080/02671522.2018.1481140.

- Alexander, R. J. 2020. A Dialogic Teaching Companion. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Aukerman, M., and M. P. Boyd. 2020. “Mapping the Terrain of Dialogic Literacy Pedagogies.” In International Handbook of Research on Dialogic Education, edited by N. Mercer, R. Wegerif, and L. Major, 373–385. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Barnes, D. 2008. “Exploratory Talk for Learning.” In Exploring Talk in School, edited by N. Mercer and S. Hodgkinson, 1–16. London: SAGE.

- Bloome, D., S. P. Carter, B. M. Christian, S. Otto, and N. Shuart-Faris. 2005. Discourse Analysis and the Study of Classroom Language and Literacy Events: A Microethnographic Perspective. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Boyd, M., and Y. Kong. 2017. “Reasoning Words as Linguistic Features of Exploratory Talk: Classroom Use and What It Can Tell Us.” Discourse Processes 54 (1): 62–81. doi:10.1080/0163853X.2015.1095596.

- Boyd, M. P., M. M. Chiu, and Y. Kong. 2019. “Signaling a Language of Possibility Space: Management of a Dialogic Discourse Modality through Speculation and Reasoning Word Usage.” Linguistics and Education 50: 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2019.03.002.

- Carter, R., and M. McCarthy. 1997. Exploring Spoken English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, R., and M. McCarthy. 2006. Cambridge Grammar of English. A Comprehensive Guide. Spoken and Written English Grammar and Usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Channell, J. 1983. “Vague Language: Some Vague Expressions in English.” PhD thes., University of York. Accessed March 2022. http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/10896/1/331631.pdf

- Channell, J. 1994. Vague Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coates, J. 1987. “Epistemic Modality and Spoken Discourse.” Transactions of the Philological Society 85 (1): 110–131. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968X.1987.tb00714.x.

- Copland, F., and A. Creese. 2015. Linguistic Ethnography: Collecting, Analysing and Presenting Data. London: SAGE.

- Cushing, I. 2021. “Policy Mechanisms of the Standard Language Ideology in England’s Education System.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 1–15. doi:10.1080/15348458.2021.1877542.

- Cutting, J., ed. 2007. Vague Language Explored. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Craft, A. 2000. Creativity across the Curriculum: Framing and Developing Practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Department for Education (DfE). 2013. “The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document.” Accessed March 2022. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/425601/PRIMARY_national_curriculum.pdf

- DIALLS. 2021a. “DIalogue and Argumentation for Cultural Literacy Learning.” www.dialls2020.eu

- DIALLS. 2021b. “Multi-Lingual Corpus.” https://dialls2020.eu/corpus/

- Duriez, C. 2002. Baboon on the Moon. Bournemouth: Arts University at Bournemouth.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hammersley, M. 2007. “Reflections on Linguistic Ethnography.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 689–695. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00347.x.

- Hardman, J. 2019. “Developing and Supporting Implementation of a Dialogic Pedagogy in Primary Schools in England.” Teaching and Teacher Education 86: 102908. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2019.102908.

- Howe, C., S. Hennessy, N. Mercer, M. Vrikki, and L. Wheatley. 2019. “Teacher–Student Dialogue during Classroom Teaching: Does It Really Impact on Student Outcomes?” Journal of the Learning Sciences 28 (4-5): 462–512. doi:10.1080/10508406.2019.1573730.

- Hymes, D. 1972. “Models of Interaction in Language and Social Life.” In Directions in Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography of Communication, edited by J. J. Gumperz and D. Hymes, 35–71. London: Basil Blackwell.

- Linell, P., L. Gustavsson, and P. Juvonen. 1988. “Interactional Dominance in Dyadic Communication.” Linguistics 26 (3): 415–442. doi:10.1515/ling.1988.26.3.415.

- Lyons, J. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Maine, F. 2015. Dialogic Readers. Children Talking and Thinking Together about Visual Texts. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Maine, F., and A. Čermáková. 2021. “Using Linguistic Ethnography as a Tool to Analyse Dialogic Teaching in Upper Primary Classrooms.” Learning, Culture and Social Interaction 29: 100500. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2021.100500.

- Maine, F., S. Rojas-Drummond, R. Hofmann, and M.-J. Barrera. 2020. “Symmetries and Asymmetries in Children’s Peer-Group Reading Discussions.” Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 43 (1): 17–33.

- Martínez, I. M. P. 2011. ““I Might, I Might Go I Mean It Depends on Money Things and Stuff”. A Preliminary Analysis of General Extenders in British Teenagers’ Discourse.” Journal of Pragmatics 43 (9): 2452–2470. doi:10.1016/j.pragma.2011.02.011.

- Maybin, J. 2009. “A Broader View of Language in School: Research from Linguistic Ethnography.” Children & Society 23 (1): 70–78. doi:10.1111/j.1099-0860.2008.00177.x.

- Mercer, N., R. Wegerif, and L. Dawes. 1999. “Children’s Talk and the Development of Reasoning in the Classroom.” British Educational Research Journal 25 (1): 95–111. doi:10.1080/0141192990250107.

- Murphy, P. K., I. A. G. Wilkinson, A. O. Soter, M. N. Hennessey, and J. F. Alexander. 2009. “Examining the Effects of Classroom Discussion on Students’ Comprehension of Text: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Educational Psychology 101 (3): 740–764. doi:10.1037/a0015576.

- Nystrand, M., A. Gamoran, R. Kachur, and C. Prendergast. 1997. Opening Dialogue: Understanding the Dynamics of Language and Learning in the English Classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

- O’Keeffe, A., M. McCarthy, and R. Carter. 2007. From Corpus to Classroom: Language Use and Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Portner, P. 2009. Modality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rampton, B. 2007. “Neo-Hymesian Linguistic Ethnography in the UK.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 11 (5): 584–607. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00341.x.

- Rojas-Drummond, S., N. Mazón, M. Fernández, and R. Wegerif. 2006. “Explicit Reasoning, Creativity and Co-Construction in Primary School Children’s Collaborative Activities.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 1 (2): 84–94. doi:10.1016/j.tsc.2006.06.001.

- Rowland, T. 2007. ““Well Maybe Not Exactly but It’s around Fifty Basically?”. Vague Language in Mathematics Classrooms.” In Vague Language Explored, edited by J. Cutting, 79–96. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sinclair, J., and M. Coulthard. 1975. Towards an Analysis of Discourse: The English Used by Teachers and Pupils. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Snell, J., and I. Cushing. 2022. ““A Lot of Them Write How They Speak”: Policy, Pedagogy, and the Policing of ‘Nonstandard’ English.” Literacy 56 (3): 199–211.

- Soter, A. O., I. A. Wilkinson, P. K. Murphy, L. Rudge, K. Reninger, and M. Edwards. 2008. “What the Discourse Tells Us: Talk and Indicators of High-Level Comprehension.” International Journal of Educational Research 47 (6): 372–391. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2009.01.001.

- Vygotsky, L. 1962. Thought and Language. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wertsch, J. 1991. Voices of the Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Wilkinson, I. A. G., A. Reznitskaya, K. Bourdage, J. Oyler, M. Glina, R. Drewry, M.-Y. Kim, and K. Nelson. 2017. “Toward a More Dialogic Pedagogy: Changing Teachers’ Beliefs and Practices through Professional Development in Language Arts Classrooms.” Language and Education 31 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1080/09500782.2016.1230129.

- Wolf, M. K., A. C. Crosson, and L. B. Resnick. 2006. “Accountable Talk in Reading Comprehension Instruction.” CSE Technical Report 670. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, and Student Testing (CRESST). Accessed March 2022. http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED492865